Are public housing projects good for kids after all?

Abstract

Is public housing bad for children? The net effect of moving into public housing on children's academic outcomes is theoretically ambiguous and likely to depend on changes to neighborhood and school characteristics. Drawing on detailed individual-level longitudinal data on New York City public school students, we exploit plausibly random variation in the precise timing of entry into public housing to estimate credibly causal effects of public housing residency on academic outcomes. Both difference-in-differences and event study analyses suggest positive effects of public housing on test scores, with larger effects after the initial year. Stalled academic performance at entry may reflect disruptive effects of residential and school mobility. Effects on test scores are larger among students who move from lower-income neighborhoods due, perhaps, to increases in neighborhood and school quality. For some subgroups, attendance improves and the incidence of obesity declines. Our results contradict the popular belief that public housing is bad for kids.

INTRODUCTION

Is public housing bad for children? Despite the best intentions, the benefits of public housing—such as improved affordability, better housing units, or greater residential stability—may be outweighed by detrimental effects of high-poverty neighborhoods, low-quality schools, neighborhood crime, or other (dis)amenities. Whether the net effect is positive or negative is theoretically ambiguous and likely to depend on the characteristics of the housing and its associated schools and neighborhoods (Cordes et al., 2022). Previous literature is discouraging, with much of the evidence based on examining exits from relatively undesirable public housing and comparing outcomes of children who left to those who remained (Chetty et al., 2016; Chyn, 2018; Jacob, 2004; Katz et al., 2001; Ludwig et al., 2013; Sanbonmatsu et al., 2006). More recent studies, however, have suggested public housing is not bad for kids. Pollakowski et al. (2022) used nationwide data and between-sibling analyses to find that public housing residency has long-term positive effects on earnings and incarceration rates. For shorter-term academic outcomes, Weinhardt (2014) and Carlson et al. (2019) focused on children's entries into oversubscribed social housing in England and public housing in Wisconsin, respectively, and found mostly null effects. Neither study, however, accounted for changes in neighborhood and school characteristics that accompanied the moves into public housing, and limitations in sample size or variation in the public housing stock may have masked positive (or negative) effects.

In this paper, we draw on detailed individual-level longitudinal data on public school students in New York City (NYC) to examine the effects of entries into public housing projects located across a wide array of neighborhoods. Exploiting plausibly random variation in the precise timing of entry into public housing, we estimate credibly causal effects of public housing on academic and weight outcomes using both difference-in-differences and event study designs. Further, we exploit heterogeneity in student “origin” neighborhoods pre–public housing entry and leverage data on public schools to explore the extent to which neighborhoods and schools shape the effects of public housing.

More specifically, we use administrative student-level data from the NYC Department of Education on NYC public school students, in grades 3 through 8, between academic years 2009 and 2017. We focus on 35,456 observations of 7,832 students who enter public housing in grades 5, 6, or 7 and have at least 1 year of standardized test scores both before and after moving into public housing. We use an expanded sample for analyzing attendance and weight outcomes, adding observations of students in grades K through 2 and 9 through 12. We begin with a difference-in-differences identification strategy, using parsimonious models that link test scores and attendance to public housing residency and student fixed effects. In our preferred estimation, we separate the effects for the first year in public housing from subsequent years and explore heterogeneity across students’ origin neighborhood types, race/ethnicity, and gender. We also implement doubly robust inverse probability weighting to our difference-in-differences specification as suggested by Callaway and Sant'Anna (2021). We further explore the characteristics of schools for students moving into and out of different neighborhoods to understand the role of public schools. We test our identification assumption of plausibly random variation in the precise timing of student entry and find little evidence of significant pre-trends.

To preview the results, we find that moving into public housing has positive and statistically significant effects on student outcomes, most prominently after the initial adjustment year. Small changes in test scores in year 1 are followed by larger improvements in subsequent years—both reading and math scores increase by roughly 0.1 standard deviations (sd). As for heterogeneity, we find positive effects for all subgroups, with larger effects for students moving from low-income neighborhoods than from high-income neighborhoods (0.10 vs. 0.07), for girls than boys (0.15 vs. 0.06), and for Asians and Whites (0.31 and 0.18, respectively) than Hispanics or Blacks (0.10 and 0.08, respectively). Moving out of low-income neighborhoods, in particular, is associated with attending better schools—with lower shares of economically disadvantaged schoolmates (that is, the share of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch) and higher average test scores. We find no significant effects for attendance or weight outcomes overall, but reductions in the probability of being obese and overweight for boys.

Taken together, our results suggest that the negative or null effects of public housing residency in previous studies may reflect the low quality or lack of diversity in public housing stocks, which are disproportionately associated with poor-quality schools or neighborhoods, or estimates that do not account for disruptive effects of residential moves into public housing. In contrast, our positive effects may be driven by improvements in schools and neighborhoods that grow over time with residential stability. Bottom line, our results refute the conclusions drawn from past studies (driven by policies that prompted exits from the least desirable projects) that public housing provides low-quality housing and neighborhoods that are bad for kids and call for future work probing the circumstances under which public housing works to improve academic outcomes for low-income students.

BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW

The promises and the problems of public housing

Public housing was the federal government's first major housing assistance program for low-income households. The U.S. Housing Act of 1937 established public housing authorities to develop public housing projects with the goal of providing “decent, safe, and sanitary dwelling for families of low-income” (p. 888). While federally funded, public housing projects are administered, managed, and operated by local public housing authorities, with examples including the Chicago Housing Authority and NYC Housing Authority (NYCHA). There are approximately 3,300 public housing authorities nationwide that serve around 1.2 million households living in public housing projects, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD, 2020). Each public housing authority sets the eligibility criteria for public housing based on household income and has its own waiting list (if any) and tenant selection and assignment process. Households living in public housing typically pay 30% of their adjusted household income towards rent, which is in most cases well below the market rate.

Despite the best intentions to provide subsidized housing units for needy families, public housing has long been criticized for its creation of “concentrations of poverty” (Massey & Kanaiaupuni, 1993). Public housing projects, typically consisting of one or more concentrated blocks of high-rise apartment buildings, were often sited in neighborhoods occupied by poor, minority residents (Schill & Wachter, 1995; Von Hoffman, 1996). For example, out of 33 projects constructed in Chicago between 1950 and 1970, all but one project were built in neighborhoods that were at least 85% Black (Hirsch, 1983). Projects often brought more tenants from low-income and minority households to the neighborhood because of the program's eligibility criteria. Critics blamed the design of public housing projects for creating isolated geographic areas that are disproportionately poor and racially Black.

Concerns about the concentration of poverty in and around public housing motivated federal housing policies to shift toward alternative housing assistance programs (Collinson et al., 2015). In the landmark case of Hills v. Gautreaux (1976), the Supreme Court ruled that the Chicago Housing Authority and the HUD discriminated against Black tenants by concentrating them in large-scale projects located in poor, Black neighborhoods. In 1992, Congress passed a new public housing funding program, HOPE VI, to replace public housing projects in distressed neighborhoods across the nation with privately owned, mixed-income projects. Tenants living in public housing buildings subject to demolition were given vouchers to move out of public housing and into other rental units in the private market. The housing choice voucher program was first created in 1974 as an alternative to the project-based approach of public housing and allowed tenants to find rental units in the private housing market. These alternative programs were often viewed by policymakers as the preferred form of housing assistance as the means to alleviate the concerns around the concentration of poverty, compared to public housing that limits the choice of residential locations to poor neighborhoods.1

However, not all eligible households are able to receive and utilize housing choice vouchers.2 Like public housing, vouchers have long waiting lists; the average waiting time for vouchers easily exceeds a year, with substantially longer waits of up to multiple years in large cities (Maney & Crowley, 2000). Even after many months on the waiting list, households are not guaranteed to successfully find housing in the private market. Low-income households—most likely under time and resource constraints—typically have 60 days to find adequate housing units that meet the federal housing quality standards and are also below the rent limits. Although prohibited by law in many states and municipalities to discriminate against the source of income to pay rent, landlords may also decline to accept vouchers (Galvez, 2011). Low-income households and minorities may be particularly vulnerable to landlord discrimination and face higher barriers when leasing up in the private housing market (Freeman, 2012; President's Commission on Housing, 1982; Tighe et al., 2017). As a result, a substantial number of voucher recipients either fail every year to successfully utilize their housing vouchers or find housing in neighborhoods not different from where they used to live.

Public housing, therefore, remains an important stream of housing assistance for low-income families that may face multiple barriers in obtaining and utilizing housing vouchers.3 As of 2020, public housing serves more than 2 million residents and 1 million households in need of housing assistance across the nation (HUD, 2020). The all-too-common long waiting lists for most public housing authorities attest that the demand remains high. While previous studies and popular press have often focused on the negative effects of poor neighborhoods surrounding public housing, there is limited causal evidence that public housing has this negative impact on children. It is crucial to understand the effects of living in public housing and the mechanisms through which it may further help or harm the residents and their children in need of housing assistance.

How might public housing affect student outcomes?

We identify four key channels through which public housing may affect student outcomes. First, moving into public housing may have income effects. Subsidized rents for public housing units, which are well below the market price, may effectively reduce rent burdens and increase disposable income. Public housing tenants typically pay 30% of their adjusted income towards rent, with some variation by local housing authorities (HUD, 2020).4 Previous studies on welfare benefits, such as Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Benefit programs, have found that increased income is likely to improve children's academic and health outcomes, especially for low-income households, as parents may have more time and financial resources available for children's education and development (Dahl & Lochner, 2012; Duncan et al., 2011; Milligan & Stabile, 2011). A study on housing choice vouchers also found that children's test scores increase by 0.02 standard deviations for every $1,000 spent on the voucher (Jacob et al., 2014). A more recent study on NYC public school students found 0.05 standard deviation increases in reading and math scores upon voucher receipt (Schwartz et al., 2020). Families in affordable housing are more likely to increase their expenditure on necessities and enrichment of their children yet experience reduced parental stress, which are all associated with improvements in children's cognitive skills and physical, social, and emotional health (Harkness & Newman, 2005; Newman & Holupka, 2017).

Second, moving into public housing may mean improved housing. That is, public housing may provide housing units of “decent, safe, and sanitary dwelling.” Improved housing conditions may include more reliable heat, water, and other utilities, as well as more space and improved privacy. Early studies suggest that public housing units provide better housing conditions, as they should meet federal housing quality standards. For instance, Currie and Yelowitz (2000) used the sex composition of children as an instrument for the relationship between families’ likelihood of living in public housing and their housing conditions. Families with two children of the opposite sex are eligible for an extra bedroom than those of the same sex and are thus more likely to apply for public housing. They find that public housing children are less likely to live in overcrowded units or high-density complexes and less likely to repeat grades. However, anecdotal evidence from the popular press suggests otherwise; dilapidated housing conditions of NYC public housing recently called attention from the popular press and nearly resulted in a federal takeover of NYCHA (Benfer, 2019; Weiser & Goodman, 2018). While there is mixed evidence on whether moving into public housing equals improved housing conditions, housing conditions are closely related to children's physical and psychological development, as well as academic performance (Coley et al., 2013; Leventhal & Newman, 2010).

Third, public housing may improve residential stability over time. Unlike families in private rental housing, public housing tenants are at lower risk of eviction or rent hikes at lease renewal (Preston & Reina, 2021).5 Improved residential stability may reduce the likelihood of disruption, as residential moves may induce involuntary school moves with timing and destination unrelated to children's best interest (Been et al., 2011; Grigg, 2012; Rumberger, 2015; Schwartz et al., 2009). Cordes et al. (2019), in particular, found that residential moves that accompany school moves are more likely to harm student performance than those that do not. “Nonstructural” school moves due to residential relocation are different from the “structural” school moves that are mandated when a student reaches the terminal grade of their current school. Nonstructural school moves are often associated with large reductions in math (but not reading) scores and graduation rates (Pribesh & Downey, 1999; Rumberger & Larson, 1998; Swanson & Schneider, 1999).6 Public housing residency may improve residential stability for low-income households and facilitate academic success for their children (Crowley, 2003; Newman & Harkness, 2002). However, entry into public housing requires a residential move and may be accompanied by a school move, imposing adjustment costs, which may (or may not) be offset over time after the initial disruption.

Finally, there may be neighborhood effects if moving into public housing means different neighborhoods—either worse or better than the alternative (or counterfactual) neighborhood. A broad literature documents the importance of neighborhood resources on children's development and academic outcomes (Chetty et al., 2016; Leventhal & Newman, 2010; Schwartz et al., 2017). While early descriptive studies showed that kids in public housing live in worse neighborhoods than those of welfare households living elsewhere (Newman & Schnare, 1997), more recent studies on NYC public housing—the setting of this study—have suggested substantial variation in public housing neighborhoods. Recent studies have documented substantial variation in the micro-neighborhood amenities, focusing on the local food environment, among students living in NYC public housing and found these differences have significant consequences for childhood obesity (Han et al., 2020; Rick et al., 2023). Dastrup and Ellen (2016) also found that most NYC public housing, originally built decades ago in low-income areas, is now surrounded by relatively high-income neighborhoods, and Schwartz et al. (2010) found students in NYC public housing do not attend worse public schools than otherwise similar peers. Therefore, it is important to examine whether moving into public housing changes neighborhood and public school quality for children.

Quasi-experimental evidence on the impacts of public housing exits and entries

Existing research identifying the causal effect of public housing residency is limited. Most of these prior studies leverage exogenous exits from public housing programs driven by mass demolitions or policy shifts towards the housing choice voucher program. The earliest studies include research on the Gautreaux mobility program, which selected households living in Chicago Housing Authority's inner-city projects to use vouchers to move to suburban neighborhoods as part of the Gautreaux litigation in 1976. The demand for the program exceeded its supply, and program participation was primarily determined by whether the applicant's telephone call went through on the registration day. Leveraging this variation, Rosenbaum and Popkin (1991) and Rosenbaum (1995) found improved academic performance among children who moved out of public housing located in extremely distressed inner-city neighborhoods and into private housing (using vouchers) in predominantly White, suburban communities.

Other studies focus on large-scale public housing demolitions in Chicago. Jacob (2004) exploited the exogenous timing of the demolition of public housing buildings in Chicago to examine the effect of public housing exits. He found no significant differences in the test scores between children who move out earlier and those who stay in the same public housing development. Jacob (2004) suggested that the null effects may be due to students moving to neighborhoods and schools that closely resemble the public housing neighborhoods they had left. Students who moved out earlier were, on average, 1.25 miles further from their original residence and in neighborhoods with lower poverty rates of around 15 pp (53% vs. 68%). However, he noted that these estimates are largely associated with a reduced share of students in extremely high-poverty tracts (70%) and that only 30% of the treatment group were living in moderate poverty tracts (between 10% and 40% poverty) with less than 3% living in low poverty tracts (lower than 10%). More importantly, there were no statistically meaningful differences in school quality, as he found only 0.1 to 0.6 percentage points difference in the share of high-performing peers that meet the national norms in math. Chyn (2018), however, examined the longer-run impacts and found that, 3 years after demolition, displaced households live in lower-poverty neighborhoods with lower crime rates, leading to later-life outcomes of improved employment and wage outcomes.

The reported gains from the Gautreaux relocation program and lasting concerns about the concentrated poverty surrounding public housing led to the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment to test whether providing housing vouchers would improve the life trajectories of the poorest families in public housing (Orr et al., 2003). Households with children living in public housing in census tracts with a poverty rate of at least 40% were eligible to participate in the experiment. The experimental group was randomly assigned to receive vouchers and mobility counseling, along with a requirement to move out of public housing and into low-poverty neighborhoods, while the control group received no vouchers but could continue to live in public housing. The Section 8 group only received vouchers without requirements to move to low-poverty neighborhoods or counseling. As a result, in the shorter term (4 to 7 years following random assignment), Kling et al. (2007) found that the experimental group and the Section 8 group were in census tracts with lower poverty rates of around 11.9 pp and 9.7 pp. In the longer term, Chetty et al. (2016) also found reductions in tract-level poverty rates by around 10 to 10.3 pp for the experimental group and 8 to 8.6 pp for the Section 8 group. However, the estimated improvements in school quality following public housing exits are substantially smaller. MTO studies have found that students in the experimental group (and the Section 8 group) attended schools that had lower shares of low-income peers by 4.8 pp (2.6 pp), lower shares of racial minorities by 3.7 pp (1.6 pp), and higher ranking in state exam by 3.1 pp (1.2 pp) but were larger in enrollment size (Sanbonmatsu et al., 2011). Results for student academic outcomes were disappointing. A series of studies has found no evidence of test score gains (or any effects on physical health, including the incidence of childhood obesity); however, depending on the subgroup, some find evidence of mental health gains and reduction in risky behaviors for girls (but not boys) and longer-term positive effects on college attendance and earnings for children who moved at younger ages (Chetty et al., 2016; Katz et al., 2001; Kling et al., 2007; Ludwig et al., 2013; Sanbonmatsu et al., 2006).

To be clear, all of these studies examined families leaving public housing located in very poor, troubled neighborhoods. Whether results generalize to public housing in better neighborhoods—perhaps with better schools—is unclear. Thus, the documented effects of public housing residency on children in previous studies, which are either negative or null, are most likely estimated at the disadvantage of public housing. These past studies also leveraged exits from public housing and compared families that are likely to continue to receive housing assistance in the form of either public housing or housing vouchers. Thus, with little variation in the effective rent paid by families, estimating the impact of public housing exits may underestimate the benefits of public housing residency regarding its income effects.

While a larger body of literature focus has focused on public housing exits, more recent evidence on public housing suggests potentially positive, if not null, effects.7 A recent study by Pollakowski et al. (2022) used national-level data on siblings who were aged 13 through 18 in 2000 with variation in exposure to subsidized housing and compares their outcomes at age 26. Using household fixed effects, they found positive effects of public housing residency, increasing earnings by 6.1% to 6.2%, which are larger gains than what they find for vouchers (2.7% to 4.8%). While only observing 1 year of post-period data, Pollakowski et al. (2022) provided credibly causal estimates of subsidized housing using between-sibling analyses and highlighted the contextual differences of previous studies that focused on a limited subset of the most distressed public housing projects. Focusing on public housing in Chicago, where projects were located in particularly high-poverty neighborhoods (e.g., Jacob, 2004; and Chyn, 2018), and cities participating in the MTO experiment, in which public housing households had to come from high-poverty neighborhoods to be eligible, likely understates public housing's overall benefit. Other MTO-specific features—e.g., requiring voucher recipients to move to low-poverty census tracts and receive counseling support to find rental units—may have further understated the relative benefits of public housing over vouchers.

Two recent quasi-experimental studies exploited exogenous timing of entry to public housing (neighborhoods) and found mostly null effects of public housing on student outcomes. Weinhardt (2014) exploited plausibly random timing of entry into social housing neighborhoods in England.8 The identification strategy leveraged the long waiting lists that give tenants little control over the precise timing of their move into social housing. He compared two key stage exam test scores of early movers who move to social housing neighborhoods in between the two exams and late movers or “future recipients” who move after the two exams. He found that early movers do not experience any detrimental effects on their test scores compared to late movers. Carlson et al. (2019) examined the impact of entry into public housing in Wisconsin, comparing test scores for 841 students who enter public housing to 604 future recipients (and other welfare recipients). They found some evidence that public housing leads to declines in math scores but null effects on reading scores.

While these recent studies on public housing entry represent important contributions, empirical limitations may have obscured any positive impact of public housing residency. First, neither accounted for the potentially disruptive effects of residential and/or school mobility, as distinct from moving into public housing per se. Thus, the estimated impacts immediately after the move may well be moderated by short-term adjustment costs. Second, neither of the studies had sufficient sample size or variation to explore heterogeneity across student subgroups and/or neighborhoods. Carlson et al. (2019) had a small public housing sample and did not explore any variation within the public housing sample in terms of demographic subgroups and neighborhoods.9 A large majority of the students in the Weinhardt (2014) sample were White (more than 80%), while public housing residents in the U.S. include large populations of Blacks and Hispanics. The significant discrimination in housing markets suggests that impacts may vary across racial/ethnic groups. As the neighborhood effects literature has found differential effects by gender, we may find further differences in the impact of public housing residency across other student demographic subgroups.

In this paper, we build upon these two papers, exploiting plausibly random variation in the precise timing of student entry to NYC public housing driven by long waiting lists and unpredictable vacancies. We use data on individual-level test scores following students up to 4 years after they move into public housing (and attendance and weight outcomes for up to 8 years). The rich longitudinal dataset, which includes indicators of the school attended, allows us to parse the potentially disruptive effects of residential and school mobility followed by entry into public housing. In addition to exploring heterogeneity by racial/ethnic subgroups and gender, we capture the differences in neighborhoods surrounding public housing projects, including their school peer characteristics, to probe potential mechanisms. Leveraging variation in student and neighborhood characteristics and controlling for residential and school moves may help reconcile findings from previous research. We also implement alternative estimators to our difference-in-differences model based on recent advances in the literature regarding potential concerns related to variation in treatment timing.

NYC PUBLIC HOUSING AND THE WAITING LIST

NYCHA—the setting of our study—is the nation's largest public housing system. As of 2020, the NYC public housing system contains 169,820 households in 2,252 buildings and 139 projects dispersed across the city's five boroughs (NYCHA, 2020).10 Roughly over 400,000 residents occupy NYC public housing, of whom approximately 26% are under age 18. Large projects located in different parts of the city are likely to provide diverse living and learning environments for NYC public housing children. Dastrup and Ellen (2016) documented that 54 public housing projects in NYC were surrounded by high-income neighborhoods in 2010, while 49 projects were in low-income neighborhoods. They found that public school quality and other neighborhood amenities are correlated with neighborhood income. In other words, NYC public housing children are exposed to a diverse set of neighborhood amenities, which may explain why public school students in NYCHA buildings do not systematically attend worse public schools than otherwise similar peers living elsewhere in the city (A. E. Schwartz et al., 2010).

Like most public housing authorities in major cities, NYCHA is oversubscribed and has its own tenant selection and assignment process, creating extensive uncertainty in the precise timing that eligible households can apply and receive an offer for public housing. First, NYC residents have little control over the timing of their application, because NYCHA closes its waiting list for public housing from time to time to control the volume of the applications it receives. When applications for public housing open, eligible households that apply are placed on the waiting list based on their family size, income, needs (e.g., emergencies), and date of application. Second, applicants have limited control over the timing of receiving offers due to the long waiting list. As of 2020, 176,646 families were on the waiting list for NYC public housing (NYCHA, 2020). In the past 5 years, the average time between “date entered waiting list” and “admission date” for NYC public housing has been more than 38 months (HUD, 2019).11 Third, applicants are unlikely to manipulate their timing of entry by waiting and rejecting offers. When applicants reach the top of the waiting list, they must select one preferred project, conditional on containing an anticipated vacancy, within 30 days. NYCHA randomly assigns applicants to vacant units in the selected project. Applicants can reject the initial offer and can receive up to two offers, but their application will be closed if they fail to accept or reject the offers within 60 days (NYCHA, 2020).12 Previous research has suggested that few households reject the initial offer for housing assistance programs with long waiting lists, as it may entail a substantial wait for and uncertainty regarding the availability of another unit (Coley et al., 2013; Rosenbaum, 1995). NYCHA closing its waiting list from time to time may further reduce households’ likelihood of rejecting offers, as it would increase their uncertainty around the chance to create new applications to get back on the waiting list.

We exploit the resulting exogenous variation in the timing that households apply for, receive offers for, and enter NYC public housing to examine the causal impact of public housing residency on student outcomes. We explore the empirical support for the proposition that the timing of public housing entry is essentially random in the following sections, testing whether the grade in which students move is uncorrelated with pre-determined student characteristics, including their test scores.

DATA, MEASURES, AND SAMPLE

We use individual-level longitudinal data from the NYC Department of Education on NYC public school students, grades 3 through 8, in academic years (AY) 2009 through 2017. These data include scores on state tests in English Language Arts and mathematics standardized by grade (z-ELA and z-Math, respectively), attendance, height and weight measures (from an annual FitnessGram®), student residential and school location, and sociodemographic variables, such as gender, race/ethnicity, grade, educational program participation (e.g., students with disability and English language learners), and economically disadvantaged students.13 In addition to the attendance rate (Attendance), we construct an indicator for chronic absenteeism (ChrncAbsent), which identifies students absent for 10 or more days in an academic year. We calculate body mass index (BMI) using student height and weight and follow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines in constructing an indicator for obesity (Obese) if BMI is at or above the 95th percentile for their age and sex and overweight (Overweight) if BMI is at or above the 85th percentile. Two indicator variable captures school and residential mobility: NewSchool equals 1 in time t if a student attends a different school in t than t−1, and NewAddress equals 1 in time t if student residential location differs between t and t−1. We also link our student-level data to longitudinal school-level data on enrollment, standardized test scores, and demographic characteristics, such as percent Black, Hispanic, Asian, White, and eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, from the New York State Annual School Report and the School Report Card.

Critically, we identify students living in NYCHA housing using student residential location and address data for NYCHA buildings. Specifically, an indicator for public housing residency, PH, equals 1 if student i lives in public housing in time t or any previous period—that is, PH equals 1 in the first year a student lives in public housing and all following years.14 We also create an indicator EntryPH, which equals 1 only in the first year a student lives in public housing, and PostPH, which equals 1 in all subsequent years. This way, we parse the immediate effects of moving into public housing—which may include potential disruptive effects of school and residential mobility—from effects in subsequent years. Similarly, we create a set of pre- and post-public housing year indicators for our event study specifications.

We identify two neighborhood types surrounding student residence before moving into public housing projects. Following Dastrup and Ellen's (2016) classification of NYC public housing neighborhoods, we define “high-income” neighborhoods as those surrounded by census block groups with average median household incomes at or above the city median in 2010 and “low-income” neighborhoods if below the median. We assign time-invariant indicator variables for students based on their “origin” neighborhoods—that is, their residential neighborhoods in time t−1 when they moved into public housing in time t. HighInc equals 1 for students if their census block group of the origin residence is surrounded by census block groups with average median household incomes at or above the city median, and LowInc equals 1 for other students.15 We also include continuous measures of neighborhood characteristics, using the average median household incomes of the surrounding census block groups (“Neighborhood income”), as well as census tract level poverty rates (“Tract-level poverty rate”), from the 2010 American Community Survey.

Since our identification strategy relies upon comparing student outcomes before and after entering public housing, we focus on three cohorts of students that enter public housing in grades 5, 6, or 7 and have at least 1 year of standardized test scores before and after entering public housing. We call these cohorts G5, G6, and G7, respectively (to be concrete, G5 are students who enter public housing in grade 5). These include 7,832 students with 35,456 pre- and post-public housing observations in grades 3 through 8. Our extended sample for attendance and weight analyses includes 40,094 pre- and post-public housing observations of students in grades K through 12.

Table 1 provides the summary statistics for our analytic sample in AY 2009, a “pre-treatment” year for all students (none live in public housing yet) by construction. Variable means are shown by public housing entry cohort. As shown, our three entry cohorts are quite similar in baseline characteristics. All cohorts are slightly overrepresented by female students (52% to 55% female), and approximately 40% are Black and 50% Hispanic, with 8% to 9% being Asian and 2% White. Virtually all are economically disadvantaged (rounded up to 100%), with standardized test scores below the NYC average in both reading (ranging between 0.31 and 0.28) and math (between 0.33 and 0.27). The earlier cohort has higher shares of chronically absent students (58% vs. 52% to 54%) but has approximately the same attendance rate as other cohorts (91% to 92%). Roughly one-quarter are obese, and 43% are overweight across all cohorts.

| Entered public housing in: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 5 (“G5”) | Grade 6 (“G6”) | Grade 7 (“G7”) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Student characteristics | |||

| Female | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| Asian | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Black | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.38 |

| Hispanic | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.52 |

| White | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Economically disadvantaged | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Student with disabilities | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| English language learner | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Grade | 3.57 | 4.36 | 4.89 |

| Student outcomes | |||

| zELA | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.31 |

| zMath | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| Attendance | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| ChrnAbsent | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| Obese | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.23 |

| Overweight | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Neighborhood characteristics | |||

| Neighborhood income | 39,815.30 | 40,386.37 | 39,941.99 |

| Change in neighborhood income | 2,451.33 | 2,696.10 | 3,023.24 |

| HighInc | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| HighOpp | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| Tract-level poverty rate | 25.75 | 25.48 | 25.90 |

| Change in tract-level poverty rate | 10.52 | 10.73 | 10.46 |

| N | 1,048 | 1,179 | 1,443 |

- Notes: Sample consists of students in grades 3 through 8 in AY 2009 through 2017, who entered public housing in grade 5 (column 1), grade 6 (column 2), or grade 7 (column 3) and have at least 1 year of standardized test scores both before and after moving into public housing.

- By construction, all observations in AY 2009 for this study's analytic sample are pre-public housing observations.

Time-invariant indicators for neighborhood characteristics before and after moving into public housing show that around 47% to 48% of these students eventually move into high-opportunity projects and 21% to 22% come from high-income neighborhoods prior to entering public housing. We find that our analytic sample of public housing students moves to neighborhoods with lower average income levels by around $2,451 to $3,024 and higher poverty rates by around 10 pp. Overall, student characteristics appear to differ little across entry cohorts prior to entering public housing, and the shares of students that move into high-opportunity projects are strikingly similar across cohorts.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

Baseline regression models

Mechanisms and heterogeneity

We then probe the intermediary underlying factors driving the differences in the effect of public housing between students from high- and low-income neighborhoods by exploring the effects on neighborhood and school characteristics. We replace Yit with a set of neighborhood- and school-level characteristics, including neighborhood income, tract-level poverty rate, school enrollment, share of economically disadvantaged peers, and school average z-scores of math and reading exams for student i in grade t. Again, we substitute LowInc and HighInc with a set of indicators for gender and race/ethnicity.

Robustness checks: Alternative specifications and samples

Finally, we conduct a series of robustness checks. We first examine whether our results are robust to alternative specifications and estimators of our difference-in-difference approaches. Our difference-in-differences setup involves multiple time periods and variation in treatment timing. Because all students in our sample enter public housing at some point during our study period, our difference-in-differences estimates are weighted averages of comparisons between early vs. later movers and later vs. early movers. In the presence of heterogeneous treatment effects, the latter comparison may bias the difference-in-differences estimates by using already treated early movers as the comparison group and may be considered a potentially “problematic” comparison (Callaway & Sant'Anna, 2021; Goodman-Bacon, 2021; Sun & Abraham, 2021). Differential trends in counterfactual outcomes may generate bias in proportion to the problematic weights. To address this, we implement an alternative difference-in-differences estimator to our baseline models using doubly robust inverse probability weighting proposed by Callaway and Sant'Anna (2021). We also explore heterogeneity by entry cohort (G5, G6, and G7). A similar pattern of treatment effects for all cohorts with heterogeneous timing of treatment (even with no untreated units included in the model) would provide some evidence in support for the hypothesis that our estimates are not subject to such bias (Goodman-Bacon, 2019; Sun & Abraham, 2021).

Second, we estimate our preferred baseline models using alternative samples. We first limit our sample to students who do not exit public housing during our study period.17 We then use an extended sample of students in grades K through 12 for attendance outcomes to examine whether results are robust to the extended grades and time span. We are able to examine non-academic student outcomes using this sample, such as student obesity and weight outcomes, for which we have data for students in grades K through 12.

Timing of moving into public housing: Testing key assumptions

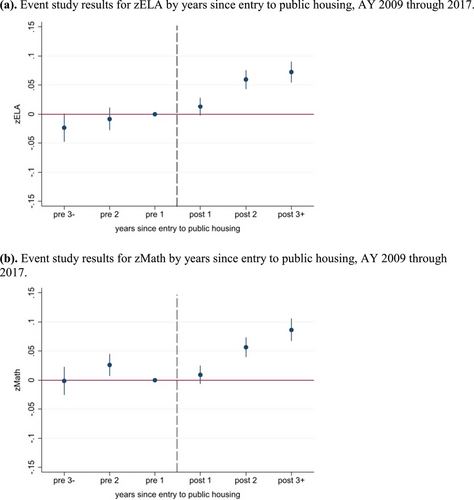

As shown in Figures 1(a) and 1(b), test scores in previous years (pre 2 and pre 3) are statistically indistinguishable from the reference year's test score (pre 1 or the year prior to entering public housing) with an exception for zMath in pre 2, for which we cannot reject the null hypothesis that all pre-public housing test scores are distinguishable from zero in a joint F-test at the 0.1 level. On the contrary, reading and math scores gradually increase after moving into public housing and are statistically distinguishable from the reference year (see post 2 and post 3+). To summarize, event study analyses show no statistically significant pre-trends, again suggesting a causal interpretation of our impact estimates is warranted.

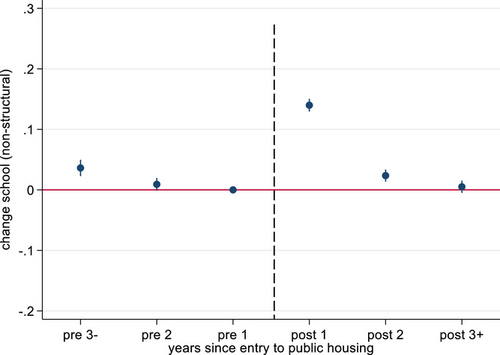

We further explore other changes that may accompany public housing entry and re-estimate the event study model replacing student test scores with an indicator for a student making a nonstructural school move for Yit. As shown in Figure 2, students are more likely to make nonstructural school moves in their first year of public housing (“post 1”) than in the year prior to public housing entry (“pre 1”).20 Students are no more likely to make nonstructural moves in other years, suggesting no distinguishable pre-trends. In other words, school moves considered disruptive are more likely to happen immediately with public housing entry than in later years, which may explain larger, positive effects in those years shown in Figures 1(a) and 1(b).

Event study results for ELA and zMath by years since entry to public housing, AY 2009 through 2017.

Notes: Figure displays point estimates and 95% confidence intervals derived from an event study of students in grades 3 through 8 in AY 2009 through 2017, who entered public housing in grades 5, 6, or 7 and have at least 1 year of standardized test scores both before and after moving into public housing (N = 36,560). The reference year is the year prior to entry (pre 1). Results for 3 or more years before or after the first year in public housing are included in year dummies for pre 3- and post 3+. F-test results for coefficients in Figure 1(a) show all pre-entry years are not jointly significant (p = 0.154) and all post-entry years are jointly significant at the 0.01 level (p = 0.000). F-test results for coefficients in Figure 1(b) show all pre-entry years are not jointly significant (p = 0.013) and all post-entry years are jointly significant at the 0.01 level (p = 0.000).

Event study results for nonstructural school moves by years since entry to public housing, AY 2009 through 2017.

Notes: See notes in Figure 1 for sample and model specification. F-test results show all pre-entry years are jointly significant (p = 0.000) and all post-entry years are jointly significant at the 0.01 level (p = 0.000).

RESULTS

Moving into public housing improves student academic outcomes

As shown in Table 2, estimates from our parsimonious model suggest that living in public housing increases reading and math scores by approximately 0.03 and 0.04 sd, respectively. Yet, attendance rate falls by 0.6 percentage points (pp), and chronic absenteeism increases by 2.7 pp. Controlling for residential and school mobility suggests larger effects on test scores (0.06 and 0.07) with no negative effects on attendance outcomes, although both moving to a new school and a new address reduce performance (0.03 and 0.02, respectively).

| Dependent variable: | zELA | zMath | Attendance | ChrnAbsent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| PH | 0.028*** | 0.060*** | 0.041*** | 0.070*** | 0.006*** | 0.002 | 0.027*** | −0.007 |

| (0.010) | (0.013) | (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.007) | (0.009) | |

| NewSchool | 0.033*** | 0.031*** | 0.007*** | 0.019*** | ||||

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.001) | (0.006) | |||||

| NewAddress | 0.023*** | 0.021*** | 0.006*** | 0.030*** | ||||

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.001) | (0.006) | |||||

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.727 | 0.727 | 0.745 | 0.745 | 0.695 | 0.697 | 0.627 | 0.628 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- Analytic sample consists of students in grades 3 through 8 in AY 2009 through 2017, who entered public housing in grades 5, 6, or 7 and have at least 1 year of standardized test scores both before and after moving into public housing. Time-varying characteristics include indicators for students with disabilities and English language learners.

Separating the immediate (first year) and later effects of living in public housing, as shown in Table 3, yields positive test score effects in the first year of 0.03 (zELA) and 0.05 (zMath), followed by larger effects of 0.09 (zELA) and 0.11 (zMath) in later years. Here, we find deleterious effects on both attendance and chronic absenteeism in the entry year become statistically insignificant in later years. Taken together, these suggest the immediate academic effects of moving into public housing are dampened, in part, by the deleterious effects of residential and school mobility, with more positive effects emerging in subsequent years as students adjust to new schools and residences.

| Dependent variable: | zELA | zMath | Attendance | ChrnAbsent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| EntryPH | 0.033*** | 0.045*** | −0.005*** | 0.024*** |

| (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.001) | (0.007) | |

| PostPH | 0.092*** | 0.105*** | 0.001 | −0.008 |

| (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.002) | (0.011) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.727 | 0.745 | 0.696 | 0.627 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- See notes in Table 2 for the analytic sample and control variables used in the models. F-test results show estimates for EntryPH and PostPH are jointly significant at the 0.01 level for columns 1 and 2; estimates for EntryPH and PostPH are statistically different at the 0.01 level for columns 1 and 2.

Are effects larger for students from poor neighborhoods?

Results in Table 4 provide mixed evidence on how neighborhoods matter. In the initial year in public housing, improvements in reading (0.04) and math (0.05) scores are substantially similar and statistically indistinguishable between students from different origin neighborhoods. However, in later years, students from lower-income neighborhoods experience larger increases in reading scores (0.10) than students moving from higher-income neighborhoods (0.08). Yet again, math score improvements in later years are not substantially and statistically different by origin neighborhood (0.11). For attendance outcomes, we find students from higher-income neighborhoods are likely to experience larger and statistically significant improvement in attendance rates (by 0.06 pp) and reduction in chronic absenteeism (by 2.9 pp). Students from lower-income neighborhoods do not experience any statistically significant changes in attendance outcomes.

| Dependent variable: | zELA | zMath | Attendance | ChrnAbsent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| EntryPH x LowInc | 0.034*** | 0.044*** | −0.006*** | 0.025*** |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.001) | (0.008) | |

| PostPH x LowInc | 0.098*** | 0.106*** | 0.000 | −0.004 |

| (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.002) | (0.011) | |

| EntryPH x HighInc | 0.028* | 0.047*** | −0.005*** | 0.021* |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.002) | (0.012) | |

| PostPH x HighInc | 0.072*** | 0.102*** | 0.004* | −0.024* |

| (0.019) | (0.020) | (0.002) | (0.014) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.727 | 0.745 | 0.696 | 0.628 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- See notes in Table 2 for the analytic sample and control variables used in the models. F-test results show estimates for all interaction terms with EntryPH or PostPH are jointly significant at the 0.01 level for columns 1 and 2; estimates for PostPH are statistically different across neighborhoods at the 0.1 level for columns 1, 3, and 4.

While we find generally positive effects of public housing regardless of origin neighborhood quality, the magnitude of the effects may depend upon the extent to which moving into public housing delivers a better or worse neighborhood. This may be, in part, due to selection of higher-achieving students into public housing with higher opportunities, which we explore below.21 We then turn to examine heterogeneity in the impact of public housing by demographic subgroups.

Heterogeneity by race/ethnicity and gender

As shown in Table 5, we find positive effects on test scores for both girls and boys and larger effects among girls, ranging up to improvements of 0.15 sd in their later years in public housing. Male students do not experience statistically significant increases in reading scores in their first year in public housing; however, both their reading and math scores improve in later years (by 0.04 and 0.06, respectively). For attendance outcomes, in Table 5 columns 3 and 4, we find no statistically significant improvements for both boys and girls.

| Dependent variable: | zELA | zMath | Attendance | ChrnAbsent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| EntryPH x Female | 0.059*** | 0.063*** | −0.005*** | 0.023*** |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.001) | (0.009) | |

| PostPH x Female | 0.142*** | 0.148*** | 0.001 | −0.002 |

| (0.016) | (0.018) | (0.002) | (0.012) | |

| EntryPH x Male | 0.005 | 0.026** | −0.006*** | 0.026*** |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.001) | (0.009) | |

| PostPH x Male | 0.038** | 0.059*** | 0.002 | −0.015 |

| (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.002) | (0.012) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.728 | 0.745 | 0.696 | 0.627 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- See notes in Table 2 for the analytic sample and control variables used in the models. F-test results show estimates for all interaction terms with EntryPH or PostPH are jointly significant at the 0.01 level for columns 1 and 2; estimates for EntryPH are statistically different across sex at the 0.01 level for columns 1 and 2; estimates for PostPH are statistically different across sex at the 0.01 level for columns 1 and 2.

As shown in Table 6, we find consistently positive effects of public housing on test scores across students from different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Asian and White students experience larger increases in test scores following entry to public housing, ranging up to improvements of 0.29 for Asians and 0.16 for Whites. We find relatively smaller but meaningful improvements in test scores among Hispanic (up to 0.09) and Black students (up to 0.08) after they move into public housing. While our analytic sample includes diverse demographic groups of students, note that 8% are Asian and 2% are White; the largest positive effects are represented by small shares of Asian and White students. For attendance outcomes, we find generally positive impacts except for White students.

| Dependent variable: | zELA | zMath | Attendance | ChrnAbsent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| EntryPH x Hispanic | 0.030** | 0.036*** | −0.005*** | 0.024*** |

| (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.001) | (0.009) | |

| PostPH x Hispanic | 0.085*** | 0.090*** | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.002) | (0.012) | |

| EntryPH x Black | 0.009 | 0.028** | −0.007*** | 0.023** |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.002) | (0.010) | |

| PostPH x Black | 0.058*** | 0.079*** | 0.001 | −0.026** |

| (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.002) | (0.012) | |

| EntryPH x Asian | 0.181*** | 0.169*** | −0.002 | 0.032** |

| (0.032) | (0.025) | (0.002) | (0.013) | |

| PostPH x Asian | 0.293*** | 0.312*** | 0.009*** | −0.008 |

| (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.002) | (0.014) | |

| EntryPH x White | 0.004 | 0.123*** | −0.000 | 0.028 |

| (0.044) | (0.046) | (0.004) | (0.034) | |

| PostPH x White | 0.157*** | 0.174*** | −0.007 | 0.081** |

| (0.044) | (0.044) | (0.005) | (0.033) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.728 | 0.746 | 0.696 | 0.628 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- See notes in Table 2 for the analytic sample and control variables used in the models. F-test results show all interaction terms with EntryPH or PostPH are jointly significant at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 4; estimates for EntryPH are statistically different across race/ethnicity at the 0.01 level for columns 1 and 2 and at the 0.05 level for column 3; estimates for PostPH are statistically different across race/ethnicity at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 4.

Probing mechanisms: Moving to better neighborhoods and schools

We examine whether the differential impact across public housing neighborhoods is attributable to the changes in the quality of neighborhoods and the public schools that students attend. As shown in Table 7, we find that the average neighborhood income decreases and the poverty rate increases following public housing entry, similar to the findings from Jacob (2004) and others. While we find decreases in school size, there are no statistically significant changes in the share of economically disadvantaged students and some evidence of reduced average standardized test scores among peers, which disappear in later years.

| Dependent variable: | Neighborhood income | Tract-level poverty rate | School Enrollment | School % ED | School-level zELA | School-level zMath |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| EntryPH | −3574.396*** | 10.771*** | −49.392*** | 0.349 | −0.012** | −0.018*** |

| (275.978) | (0.204) | (5.368) | (0.221) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| PostPH | −2711.139*** | 9.079*** | −50.882*** | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.000 |

| (386.826) | (0.290) | (7.955) | (0.320) | (0.007) | (0.008) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.603 | 0.606 | 0.617 | 0.615 | 0.700 | 0.718 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- See notes in Table 2 for the analytic sample and control variables used in the models. F-test results show EntryPH and PostPH are jointly significant at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 4 and 6; estimates for EntryPH and PostPH are statistically different at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 4 and 6.

However, as shown in Table 8, neighborhood and school peer characteristics change in different directions depending on whether students move out of low-income or high-income neighborhoods. Students from high-income neighborhoods are likely to experience a drastic decrease in neighborhood income levels after public housing entry. Similarly, we find an increase in the share of poor peers of around 2 pp and reductions in both school-level reading and math scores for these students (of around 0.04 to 0.05). We do not find such drops in neighborhood and school quality for students moving from lower-income neighborhoods but, instead, increases in peer reading and math scores of around 0.02 in later years. These changes in peer test scores may explain the larger positive gains in reading scores for students moving from lower-income neighborhoods found in Table 4.

| Dependent variable: | Neighborhood income | Tract-level poverty rate | School Enrollment | School % ED | School-level zELA | School-level zMath |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| EntryPH x LowInc | 1393.865*** | 7.876*** | −62.694*** | −0.084 | −0.003 | −0.009 |

| (246.492) | (0.207) | (5.673) | (0.229) | (0.005) | (0.006) | |

| PostPH x LowInc | 1520.486*** | 6.878*** | −69.162*** | −0.633* | 0.017** | 0.013 |

| (353.212) | (0.288) | (8.146) | (0.324) | (0.007) | (0.008) | |

| EntryPH x HighInc | −20394.638*** | 20.593*** | −3.684 | 1.841*** | −0.044*** | −0.046*** |

| (565.513) | (0.340) | (9.057) | (0.386) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| PostPH x HighInc | −17261.078*** | 16.671*** | 12.344 | 2.235*** | −0.035*** | −0.043*** |

| (591.746) | (0.386) | (10.629) | (0.447) | (0.010) | (0.011) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.653 | 0.633 | 0.618 | 0.616 | 0.701 | 0.718 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- See notes in Table 2 for the analytic sample and control variables used in the models. F-test results show all interaction terms with EntryPH or PostPH are jointly significant at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 6; estimates for EntryPH are statistically different across neighborhoods at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 6; estimates for PostPH are statistically different across neighborhoods at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 6.

In Table 9, we find that female students attend schools with higher standardized test scores for both reading and math by 0.02 after they move into public housing, while male students attend schools with lower scores by 0.02 to 0.03 in the initial year and around 0.01 for reading to 0.02 for math in later years. These changes in school peer characteristics may explain larger improvements in test scores and attendance outcomes among female students found in Table 5. As for race and ethnicity, results in Table 10 show that Asian students experience the most dramatic changes in peer characteristics after moving into public housing; they attend schools with peer test scores that are up to 0.05 higher in the initial year and 0.14 higher for reading and 0.11 for math in later years than their pre-treatment years. On the contrary, Hispanic and Black students experience a drop in school-level standardized test scores by around 0.01 to 0.03 in the initial year, but the changes become statistically insignificant in later years. These may explain positive yet smaller improvements in student test scores for Hispanic and Black students found in Table 6. Students of different demographic subgroups may leverage changes in housing and neighborhood in disparate ways, including the choice of public schools to attend. Our results suggest that the resulting characteristics of public schools attended by demographic subgroups may be driving the differences in the magnitude of our estimated impact of moving into public housing.

| Dependent variable: | Neighborhood income | Tract-level poverty rate | School Enrollment | School % ED | School-level zELA | School-level zMath |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| EntryPH x Female | −3598.757*** | 10.578*** | −52.895*** | 0.073 | −0.003 | −0.011 |

| (349.957) | (0.251) | (6.489) | (0.265) | (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| PostPH x Female | −2738.135*** | 8.944*** | −61.891*** | -0.048 | 0.023*** | 0.017** |

| (433.520) | (0.320) | (8.709) | (0.348) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| EntryPH x Male | −3548.155*** | 10.979*** | −45.689*** | 0.649** | −0.022*** | −0.025*** |

| (328.721) | (0.255) | (6.484) | (0.266) | (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| PostPH x Male | −2681.714*** | 9.226*** | −38.912*** | 0.075 | −0.014* | −0.018** |

| (418.972) | (0.322) | (8.704) | (0.350) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.603 | 0.606 | 0.617 | 0.615 | 0.701 | 0.718 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- See notes in Table 2 for the analytic sample and control variables used in the models. F-test results show all interaction terms with EntryPH or PostPH are jointly significant at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 3 and 5 through 6; estimates for EntryPH are statistically different across sex at the 0.01 level for columns 5, at the 0.05 level for column 6, and at the 0.1 level for column 4; estimates for PostPH are statistically different across sex at the 0.01 level for columns 3, 5, and 6.

| Dependent variable: | Neighborhood income | Tract-level poverty rate | School Enrollment | School % ED | School-level zELA | School-level zMath |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| EntryPH x Hispanic | −2703.289*** | 9.054*** | −70.680*** | 0.360 | −0.011* | −0.018*** |

| (339.435) | (0.249) | (6.621) | (0.266) | (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| PostPH x Hispanic | −2267.473*** | 7.879*** | −88.058*** | 0.468 | −0.008 | −0.014 |

| (429.785) | (0.316) | (8.744) | (0.345) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| EntryPH x Black | −4359.382*** | 11.830*** | −36.771*** | 0.928*** | −0.025*** | −0.029*** |

| (364.274) | (0.275) | (6.609) | (0.275) | (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| PostPH x Black | −3414.994*** | 10.023*** | −37.711*** | 0.781** | −0.006 | −0.006 |

| (444.798) | (0.340) | (8.824) | (0.358) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| EntryPH x Asian | −2107.136*** | 13.972*** | 3.602 | −3.260*** | 0.048*** | 0.049*** |

| (676.567) | (0.535) | (14.851) | (0.638) | (0.015) | (0.015) | |

| PostPH x Asian | −907.700 | 11.248*** | 64.304*** | −7.864*** | 0.142*** | 0.112*** |

| (667.627) | (0.545) | (15.328) | (0.640) | (0.016) | (0.016) | |

| EntryPH x White | −14003.753*** | 16.563*** | 11.193 | 2.518** | −0.002 | −0.022 |

| (2291.780) | (1.260) | (31.122) | (1.145) | (0.024) | (0.027) | |

| PostPH x White | −5019.797*** | 7.746*** | 106.968*** | 5.250*** | 0.029 | 0.038 |

| (1222.686) | (0.902) | (31.101) | (1.173) | (0.025) | (0.027) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R2 | 0.605 | 0.609 | 0.620 | 0.620 | 0.703 | 0.719 |

| N obs | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 | 35,456 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- See notes in Table 2 for the analytic sample and control variables used in the models. F-test results show all interaction terms with EntryPH or PostPH are jointly significant at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 6; estimates for EntryPH are statistically different across race/ethnicity at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 6; estimates for PostPH are statistically different across race/ethnicity at the 0.01 level for columns 1 through 6.

Robustness checks and other outcomes

First, we conduct a series of robustness checks for our difference-in-differences estimation and find that the results are not sensitive to alternative samples and specifications. We re-estimate our model using doubly robust inverse probability weighting suggested by Callaway and Sant'Anna (2021), which we refer to as the CSDID estimator, and show the results in Tables 11 and 12. As shown in Table 11 panel A, we find, overall, positive post-period CSDID estimates for zELA, zMath, and Attendance. Dynamic event study results using the CSDID estimator in Table 11 panel B also show that the positive effects of public housing residency on test scores and attendance outcomes are concentrated in later years (post 2), where both zELA and zMath increase by around 0.1 sd and Attendance increases by 1 pp. The test score results are similar to those in our main specification shown in Table 3, where we also find statistically significant increases of around 0.09 and 0.1 sd in zELA and zMath, respectively, in PostPH. For attendance, while our main specification (in Table 3) suggests positive but statistically insignificant effects of PostPH on attendance rates, the CSDID estimator finds larger, statistically significant increases of around 1 pp. Thus, our main specification may underestimate the positive effects of public housing residency on attendance outcomes. Both our main specification and the CSDID estimator find statistically insignificant effects on chronic absenteeism.

| Dependent variable: | zELA | zMath | Attendance | ChrnAbsent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Panel A: Simple aggregation of all post-treatment effects | ||||

| PH | 0.060*** | 0.060*** | 0.004** | −0.007 |

| (0.019) | (0.020) | (0.002) | (0.013) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Panel B: Dynamic event study effects | ||||

| Post 1 | 0.019 | 0.020 | −0.002 | 0.016 |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.001) | (0.010) | |

| Post 2 | 0.100*** | 0.101*** | 0.010*** | −0.031 |

| (0.027) | (0.029) | (0.003) | (0.019) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N obs | 34,574 | 34,574 | 34,574 | 34,574 |

- Notes: Estimates are calculated using the csdid package in Stata (Callaway & Sant'Anna, 2021), and pre-period estimates are suppressed in both panels. Standard errors are shown in parentheses (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

- Analytic sample consists of students in grades 3 through 8 in AY 2009 through 2017, who entered public housing in grades 5, 6, or 7 and have at least 1 year of standardized test scores both before and after moving into public housing. Observations for repeated grades (n = 882) are omitted from the model due to repeated time values within panel. Time-varying characteristics include indicators for students with disabilities and English language learners.

| Dependent variable: | zELA | zMath | Attendance | ChrnAbsent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Panel A: Simple aggregation of all post-treatment effects | ||||

| PH | 0.074*** | 0.062*** | 0.004** | −0.008 |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.002) | (0.013) | |

| Student FE & Grade FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Panel B: Dynamic event study effects | ||||

| Post 1 | 0.023 | 0.019 | −0.002 | 0.016 |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.001) | (0.010) | |

| Post 2 | 0.126*** | 0.104*** | 0.010*** | −0.032* |

| (0.029) | (0.030) | (0.003) | (0.019) | |

| Student FX & Grade FX | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N obs | 34,574 | 34,574 | 34,574 | 34,574 |

We also find substantively similar results where we re-estimate the baseline model using the CSDID estimator without controlling for time-varying student characteristics, which may be endogenous to treatment (see Table 12).22 Again, our results are not sensitive to these alternative specifications of the difference-in-differences models.

We then examine whether the effects are different by entry cohort—G5 (Appendix Figures A.1a and A.1b), G6 (Appendix Figures A.2a and A.2b), and G7 (Appendix Figures A.3a and A.3b). Event study results suggest that if we stratify our analytic sample by cohort of entry into public housing, we still see no significant pre-trends in standardized test scores in either reading or math but do see statistically significant steady improvements in test scores post-entry across all cohorts.

Results are also robust to measuring the outcomes excluding public housing exiters in Appendix Table A.6. Our intent-to-treat approach in identifying public housing residency considers students who exit public housing after their first year to still be “treated” by public housing. We exclude students who ever leave public housing from our sample and still find consistently positive and statistically significant impacts of public housing residency on student academic performance.

Finally, we extend our sample of students to all K–12 students who entered public housing in grades 5, 6, or 7 to examine the longer-term impact on student attendance and weight outcomes. Similar to our results for students in grades 3 through 8, we find that public housing residency has no significant impact on student attendance outcomes overall, with potentially a small increase in attendance rates in later years (see Appendix Table A.7). We also examine student weight outcomes and find no significant changes in their likelihood of being obese or overweight. Examining heterogeneity in weight outcomes by sex, we find some evidence of statistically significant reductions in the probability of being obese and overweight for boys after their initial year in public housing (see Appendix Table A.8).

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

Spurred by concerns about the negative effects of concentrated poverty in public housing neighborhoods, past studies have focused on examining the effects of moving children out of the most distressed public housing projects in the nation (Chetty et al., 2016; Chyn, 2018; Jacob, 2004; Katz et al., 2001; Ludwig et al., 2013; Sanbonmatsu et al., 2006). Yet, most of these studies found null effects of public housing exits on short-term academic outcomes. More recent studies that have focused on entries into oversubscribed public housing also found mostly null effects (Weinhardt, 2014; Carlson et al., 2019). Though not examining student outcomes, Pollakowski et al. (2022) used nationwide data and between-sibling analyses to find that public housing residency has long-term positive effects on earnings and incarceration rates. Our study adds to the literature and provides credibly causal evidence that public housing residency improves academic outcomes for NYC public school students. After the initial year in public housing, the year in which students make residential moves, by definition, and are highly likely to make school moves, we find student performance in reading and math exams increases by 0.09 and 0.11 sd. Our results suggest steady improvements over time, with little evidence of significant pre-trends in test scores. Stalled academic performance in the first year of entry may reflect potentially disruptive effects of residential and school moves in addition to any benefits of public housing. Residential and school mobility may play a key role in reconciling previous evidence on the null effects of moving into public housing from Weinhardt (2014) and Carlson et al. (2019), as they did not explore the effects of disruptive moves from the impact of entering to public housing.

Moreover, our results are based on public housing projects located in a diverse set of NYC neighborhoods, including those with average household incomes higher than the city median. Our findings of public housing's positive effects on children differ from the findings from previous studies drawing on the Gautreaux relocation program, mass public housing demolitions in Chicago, and the MTO experiment, which all focused on exits from extremely distressed public housing neighborhoods. Public housing, when supported by sufficient neighborhood resources, may have substantial positive impacts on student academic performance, given its income effects and potential improvements in housing conditions and residential stability.23 In fact, we find that students moving from lower-income neighborhoods experience larger gains in test score outcomes, suggesting that changes to the neighborhoods may matter. However, note that public housing has positive effects regardless of neighborhood income level. This may suggest that the remaining mechanisms through which public housing changes children's living environment, other than neighborhoods, may effectively improve student outcomes—namely, income effects and improvements in housing conditions. Schwartz et al. (2020) similarly examined NYC public school students but those who eventually receive housing vouchers and found that they perform 0.05 sd better, on average, in both reading and math scores after voucher receipt. We find comparable improvements of around 0.03 to 0.04 sd in student reading and math scores after moving into public housing, altogether pointing towards plausible income effects through which housing assistance can improve student outcomes.

Our data also include a diverse set of students that may provide more nuanced evidence on the impact of public housing by student demographic subgroups. We find larger improvements in test scores for girls (0.15 sd) than for boys (0.06 sd). These results are similar to the findings from the MTO studies that girls benefit more from transitions to low-poverty neighborhoods relative to boys. For reference, Weinhardt (2014) and Carlson et al. (2019) did not find any statistically meaningful differences between girls and boys. We also explore heterogeneity by racial and ethnic groups and find that public housing residency has positive impacts not only on Black and White students but also on Hispanic and Asian children, who are little represented in previous literature. The positive effects on test scores are smaller for Black and Hispanic students (0.08 to 0.09 sd) than for White and Asian students (0.16 and 0.29 sd, respectively), similar to findings from Schwartz et al. (2020), where Black students experience small to no gains from voucher receipt and Hispanic, White, and Asian students see significant gains. Previous studies on public housing mostly focus on geographic areas with a less diverse body of students. For example, public housing kids in Chicago, included in Jacob (2004) and Chyn (2018), are around 96% and 98% Black, and the sample of students in England's social housing neighborhoods from Weinhardt (2014) is roughly 84% White. As an exception, the sample of students on housing assistance in Wisconsin from Carlson et al. (2019) is 40% Black and 44% White; however, they do not specify the demographic breakdown between students on housing choice vouchers and in public housing and—due to the small public housing sample—are unable to explore heterogeneity by race. Our sample of NYC public housing children are 41% Black and 49% Hispanic, the remaining being 8% Asian and 2% White.

Our event study analyses and comparisons of different entry cohorts by grade suggest little concern regarding exogenous timing of public housing entry, the key assumption of this paper's identification strategy. We find little evidence of pre-existing trends in student outcomes that lead up to public housing entry, and students who enter public housing in earlier vs. later grades do not appear to differ in terms of their pre-determined characteristics. In other words, as found in Weinhardt (2014) and Carlson et al. (2019), we also find that new tenants for an oversubscribed public housing system are unlikely to exercise control over the timing of entry. Yet, if available, additional information about the allocation process (e.g., how long each household stayed on the waiting list or whether each household has accepted, vs. rejected, the initial offer) may provide more direct insight into the extent to which households have control over the precise timing of public housing entry.