Are Parental Welfare Work Requirements Good for Disadvantaged Children? Evidence From Age-of-Youngest-Child Exemptions

Abstract

This paper assesses the impact of welfare reform's parental work requirements on low-income children's cognitive and social-emotional development. The identification strategy exploits an important feature of the work requirement rules—namely, age-of-youngest-child exemptions—as a source of quasi-experimental variation in first-year maternal employment. The 1996 welfare reform law empowered states to exempt adult recipients from the work requirements until the youngest child reaches a certain age. This led to substantial variation in the amount of time that mothers can remain home with a newborn child. I use this variation to estimate the impact of work-requirement-induced increases in maternal employment. Using a sample of infants from the Birth cohort of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, the reduced form and instrumental variables estimates reveal sizable negative effects of maternal employment. An auxiliary analysis of mechanisms finds that working mothers experience an increase in depressive symptoms, and are less likely to breastfeed and read to their children. In addition, such children are exposed to nonparental child care arrangements at a younger age, and they spend more time in these settings throughout the first year of life.

INTRODUCTION

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996 aggressively sought to reduce the dependence of single mothers on cash assistance and increase their participation in the labor force. One of the central elements of the PRWORA was the implementation of work requirements with which adults must comply to be eligible for cash assistance. In addition, the law allowed sanctions to be levied on those who failed to comply with the work requirements, and it created a federally mandated 60-month time limit on benefit receipt.

In the 20 years following the passage of PRWORA, the scholarly literature has established that the legislation was moderately effective at reducing the incidence of welfare participation and promoting work among single mothers (Grogger, 2003, 2004; Herbst, 2008; Kaushal & Kaestner, 2001; Mazzolari, 2007; Meyer & Rosenbaum, 2001). Indeed, some estimates suggest that welfare reform alone accounted for as much as one-quarter of low-skilled mothers’ employment growth throughout the 1990s (Fang & Keane, 2004). In addition, the legislation had far-reaching effects on material well-being (Kaushal, Gao, & Waldfogel, 2007; Meyer & Sullivan, 2004), marriage and divorce (Bitler et al., 2004; Graefe & Lichter, 2008), fertility (Lopoo & DeLeire, 2006), health (Bitler, Gelbach, & Hoynes, 2005; Kaestner & Kaushal, 2003; Kaestner & Tarlov, 2006), and a variety of other adult outcomes.

One issue that has received significantly less attention is the effect of welfare reform on child well-being. To be sure, Ziliak's (2015) extensive review of the literature concludes that although the “historical underpinning of TANF is on improving child welfare, … some of our weakest causal evidence to date on welfare reform is in this domain” (p. 89). Of particular importance are the legislation's work requirements, which directed large numbers of nonexempt mothers—many with young children—to participate in work-related activities for at least 30 hours per week. Today approximately 60 percent of welfare recipients must comply with the work requirements, whereas prior to welfare reform they were largely shielded from these rules. In addition, children under age six account for nearly half of all children receiving welfare.1 Given the importance of these early years for children's cognitive and social-emotional development, the question of the impact of work requirements on child well-being is an important one for scholars and policymakers. The goal of this paper, therefore, is to provide some of the first causal evidence on this question.

Economic theory offers ambiguous predictions about the impact of the PRWORA's work requirements on child development. The most obvious mechanism for a positive effect is through an increase in family income, which can be used to purchase household technologies that enhance child health and development. In addition, some mothers may obtain or improve the family's health insurance coverage through an employer-provided plan. Attachment to the workforce can also benefit mothers’ mental health and sense of personal control, which in turn may lead to increased household stability and higher quality parenting. On the other hand, it is possible that the income available to invest in child development remains flat or even declines, given that welfare benefits may be phased out and mothers might divert resources away from children in order to cover work-related expenses. Furthermore, work requirements may decrease the quantity and quality of maternal time investments in children, while simultaneously increasing children's exposure to lower quality nonmaternal care. Finally, household stability could be negatively affected if the work mandates are not flexible enough (or support services are unavailable) to accommodate mothers with little work experience and skills as well as substance abuse or mental health issues.

This paper exploits an important feature of states’ work-activity requirements to identify the causal effect of maternal employment on the cognitive development of disadvantaged children. I use age-of-youngest-child exemptions (AYCEs) from the work requirements as a source of plausibly exogenous variation in first-year maternal employment. The PRWORA authorized states to exempt adult welfare recipients from the work requirements until the youngest child reaches a certain age. This produced substantial variation in the amount of time that mothers can remain home with a newborn child, ranging from zero to 24 months as of the early 2000s. In addition, many states provide mothers with different AYCEs depending on the birth order of the child. A comparatively generous exemption is provided after a woman's first child, while shorter exemptions are given after higher order births. Finally, I exploit idiosyncratic variation in the child's age-at-assessment to distinguish between mothers with different AYCEs simply because their children were assessed at different ages. These sources of variation are used to calculate the number of months remaining in mothers’ exemption from the work requirements. I use this variable as an instrument to estimate the effect of work-requirement-induced increases in early maternal employment. Thus, the instrumental variable (IV) estimates in this paper are important from a policy perspective.

I apply states’ AYCE policies to infants and their mothers in the Birth Cohort of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS-B), a large nationally representative study of children born in 2001. I rely primarily on the nine-month survey in which children were administered a cognitive ability test and mothers provided comprehensive information about the family. An advantage of the ECLS-B is that it allows researchers to construct a detailed history of maternal labor supply since the focal child's birth. I use this information to examine two measures of maternal employment in the first year of the child's life: an indicator for any employment and the cumulative number of months employed.

The paper's main results are summarized as follows. I first show that states’ AYCE time allotments are highly correlated with mothers’ employment decisions. Estimates from the first-stage equation indicate that reductions in mothers’ exemption increases the likelihood of engaging in any work since childbirth (F = 31.0) as well as the number of months employed (F = 24.5). Specifically, each one-month reduction in the AYCE increases the amount of work by nearly 0.5 months. In addition, the instrument passes a number of falsification and exogeneity tests: it is uncorrelated with the work decisions of mothers ineligible for welfare, and it is uncorrelated with a variety of pretreatment characteristics. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimates from the child ability production function suggest that children of working mothers score higher on the nine-month Bayley Short Form Research Edition (BSF-R) test than their counterparts whose mothers do not work. However, when states’ exemption policies are used to instrument for maternal work, I find that test scores are lower among children of working mothers. Each month of employment in the first year is estimated to reduce test scores by 0.08 SDs. In addition, these adverse effects persist to the second year of life, although they fade by kindergarten entry. A supplementary analysis of mechanisms finds that working mothers experience an increase in depressive symptoms, are less likely to breastfeed and read to their children, and experience behavioral complications with the child. Furthermore, such children are exposed to nonparental child care arrangements at a younger age, and they spend more time in these settings throughout the first year of life.

This paper contributes to a number of closely related literatures studying the impact of U.S. tax and transfer programs on parental employment and child development. It contributes primarily to the large literature analyzing the effect of welfare reform on single mothers’ employment (noted above), as well as the comparatively small literature studying the developmental implications of welfare reform generally or work requirements specifically (Bernal & Keane, 2011; Haider, Jacknowitz, & Schoeni, 2003; Kaestner & Lee, 2005; Washbrook et al., 2011). It also complements the papers studying the impact of PRWORA-related policies and programs, such as earnings disregards and child care subsidies, on parental labor supply and child development (e.g., Herbst & Tekin, 2016, 2014; Matsudaira & Blank, 2014). More broadly, this paper is relevant to the large literature evaluating the influence of other safety-net programs—including the Earned Income Tax Credit; Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program; and Medicaid—on children's short- and long-run health, education, and labor market outcomes (Bitler & Currie, 2005; Dahl & Lochner, 2012; Hoynes, Miller, & Simon, 2015; Hoynes, Schanzenbach, & Almond, 2016; Miller & Wherry, 2014; Rossin-Slater, 2013). Given the similarities between AYCEs and maternity leave policies, this analysis is also germane to the literature analyzing the effect of leave-taking on mothers’ post-birth employment as well as child well-being (Hill, 2012; Rossin, 2011; Rossin-Slater, Ruhm, & Waldfogel, 2013).

Finally, this paper contributes to the literature studying the direct relationship between early maternal employment and child development. This research generally finds negative effects of first-year employment and neutral or even positive effects of later employment (Brooks-Gunn, Han, & Waldfogel, 2002; James-Burdumy, 2005; Ruhm, 2004; Waldfogel, Han, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). A persistent concern in this literature is the possibility that unobserved selection into employment biases the effect of maternal work. Most studies attempt to overcome the omitted variables problem by controlling for a rich set of family characteristics (e.g., Ruhm, 2004) or through a fixed effects estimator (e.g., James-Burdumy, 2005; Waldfogel , Han & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). The use of instrumental variables is less common (Bernal & Keane, 2011; Morrill, 2011), largely because of difficulties finding credible instruments for maternal employment. Thus, this paper represents one of the first attempts to instrument for early maternal employment.

BACKGROUND ON AGE-OF-YOUNGEST-CHILD EXEMPTIONS

Following the passage of the PRWORA, all states required adult welfare recipients to participate in an acceptable work activity for at least 30 hours per week within 24 months of receiving assistance.2 Although they vary by state, acceptable work activities generally include subsidized and unsubsidized employment, job training, GED or postsecondary course-taking, and community service. States are given the authority to grant exemptions from the work requirements for a myriad of reasons. One such exemption, referred to as an age-of-youngest-child exemption (AYCE), allows mothers to remain home in order to provide care for an infant or toddler.3 Prior to the PRWORA, most states set the exemption at 36 months, meaning that mothers could receive cash assistance without fulfilling a work requirement until the youngest child reached 36 months of age. However, the 1996 legislation stipulates that states may, but are not required to, exempt mothers with young children from participating in work-related activities. The law's flexibility had the effect of both reducing the average length of and increasing the variation in AYCEs across the states. These changes imply that over time a growing number of new mothers have been exposed to states’ work requirements, and that considerable geographic variation exists in the amount of time a mother is allowed to remain home with a newborn. Table 1 summarizes the key features of states’ AYCE provisions for 2001, the relevant year for the current analysis (Urban Institute, 2001). Although a 36-month exemption was the norm prior to welfare reform, no state provided such a generous allotment five years after reform. The baseline AYCE ranges from zero to 24 months. Four states provided new mothers with no exemption, 19 states provided them with one lasting less than 12 months, and 28 states granted an exemption of 12 or more months.

| State | Baseline | 2+ Births | Lifetime |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 3 | ||

| Alaska | 12 | 0 | |

| Arizona | 0 | ||

| Arkansas | 3 | ||

| California | 12 | 0 | |

| Colorado | 12 | ||

| Connecticut | 12 | ||

| Delaware | 3 | ||

| District of Columbia | 12 | ||

| Florida | 3 | ||

| Georgia | 12 | 0 | |

| Hawaii | 6 | ||

| Idaho | 0 | ||

| Illinois | 12 | ||

| Indiana | 3 | ||

| Iowa | 2.77 | ||

| Kansas | 12 | ||

| Kentucky | 12 | 0 | |

| Louisiana | 12 | 0 | |

| Maine | 12 | 0 | |

| Maryland | 12 | 0 | |

| Massachusetts | 24 | ||

| Michigan | 3 | ||

| Minnesota | 12 | ||

| Mississippi | 12 | 0 | |

| Missouri | 12 | ||

| Montana | 0 | ||

| Nebraska | 3 | ||

| Nevada | 12 | 0 | |

| New Hampshire | 24 | ||

| New Jersey | 3 | ||

| New Mexico | 12 | 0 | |

| New York | 3 | ||

| North Carolina | 12 | 0 | |

| North Dakota | 4 | ||

| Ohio | 12 | ||

| Oklahoma | 3 | 12 | |

| Oregon | 3 | ||

| Pennsylvania | 12 | 0 | |

| Rhode Island | 12 | ||

| South Carolina | 12 | ||

| South Dakota | 3 | ||

| Tennessee | 4 | ||

| Texas | 24 | ||

| Utah | 0 | ||

| Vermont | 18 | ||

| Virginia | 18 | ||

| Washington | 4 | 12 | |

| West Virginia | 12 | 6 | |

| Wisconsin | 3 | ||

| Wyoming | 3 | 12 |

- Source: Urban Institute (2001). The Welfare Rules Database.

In addition to setting the AYCE allotment, states have the authority to establish the characteristics of families to which these allotments apply. As shown in Table 1, 13 states established policies that use the child's birth order to determine the AYCE. In particular, a comparatively generous allotment was provided to women having their first child, while mothers’ higher order births were given a substantially smaller allotment. The most common approach—taken in 12 of the 13 states—was to set the exemption at 12 months for the first child and zero months for each subsequent child. The only exception was West Virginia, which provided a six-month AYCE to all higher order births.

Still another strategy, utilized in three states, was to provide a lifetime AYCE allotment that could be used for multiple children. However, states specified the maximum number of months that may be allocated to each newborn. Washington provided mothers with a lifetime AYCE of 12 months, stipulating that an exemption of no more than four months could be applied to a given child. Such a policy implies that the AYCE in Washington was zero months starting with the fourth child. Oklahoma and Wyoming also provided a 12-month lifetime exemption, but these states stipulated that no more than three months could be allocated to each child. Finally, South Carolina used characteristics such as mothers’ age and educational attainment to establish different exemptions. Here, the baseline AYCE of 12 months applied only to mothers ages 26 and older who have at least a high school degree; mothers not meeting these criteria were given zero months of exempt time.4

RELEVANT LITERATURE

As noted above, multiple streams of research are relevant to the current study. This discussion focuses on the literature examining the impact of welfare reform—including AYCEs—on child well-being. An early study by Paxson and Waldfogel (2003) examines the prevalence of child abuse and foster care placements. A key finding is that enactment of an immediate work requirement is associated with increases in the number of children in foster care. Haider, Jacknowitz, and Schoeni, (2003) consider the relationship between states’ work requirement rules and rates of breast feeding. The authors find that moderate to strict work requirements are associated with reductions in breast feeding. A more recent paper by Kaestner and Lee (2005) is one of the few to examine direct measures of child well-being, although it does not consider work requirements per se. Using National Natality Files from 1992 to 2000, their findings indicate that welfare reform led to small declines in first trimester prenatal care and increases in the incidence of low birth weight. Particularly relevant is the analysis by Bernal and Keane (2011), who exploit a large number of welfare reform characteristics, including work requirements, as instruments for maternal work and child care use. Their estimates show that each year of work and child care exposure reduces mental ability test scores by 2.1 percent.5

To my knowledge, two published papers examine the impact of AYCEs, only one of which considers direct measures of child development. Hill (2012) uses the June Current Population Survey between 1998 and 2008 to examine the relationship between states’ exemptions and the employment of new mothers. The author finds that mothers exposed to AYCEs of 12 or more months are less likely to work full-time than those not exposed to an exemption. The second paper, by Washbrook et al. (2011), also using the ECLS-B, similarly finds that mothers residing in states with longer AYCEs are less likely to work in the first year after childbirth. However, despite delaying mothers’ entry into the labor market, the authors find that these exemptions are not related to intermediate determinants of child development (e.g., breast feeding, maternal depression, and parenting skills), nor do they influence direct measures of cognitive and behavioral development at the start of preschool.

This paper makes several contributions. First, the analysis focuses on the implications of early maternal employment for the development of disadvantaged children, as defined by mothers’ marital status and educational attainment. Most studies in the maternal employment literature analyze economically diverse samples, making the results less salient to families at risk of receiving welfare. Second, this paper yields estimates of the causal effect of maternal employment by implementing a unique IV strategy to deal with the possibility of endogenous work decisions. Thus, it stands with Bernal and Keane (2011) and Morrill (2011) as the only papers to utilize credible instruments for maternal employment. Third, this is one of the first papers to estimate the impact of work requirements—arguably the most important feature of welfare reform—on direct measures of child development, including cognitive ability tests and indices of social-emotional skills. It does so by improving upon the measurement of AYCEs relative to previous work. Both studies discussed above code these policies through one or more state-level dummy variables indicating the length of the work requirement exemption. Specifically, Hill (2012) creates separate indicators for AYCEs of zero months, three to nine months, and 12 months or more. Washbrook et al. (2011) create a single indicator for an AYCE of 12 months or more. Therefore, the identifying variation in these papers is largely driven by cross-state variation in the length of the exemption. This paper improves the coding of AYCEs by first exploiting this cross-state policy variation. It then takes advantage of the differential policy treatment depending on the child's birth order. It also exploits the rules on lifetime allotments, which are used to exempt mothers until the maximum number of months is reached. Finally, the paper uses information on the focal child's age-at-assessment to distinguish between mothers with varying AYCE allotments simply because their children were different ages when they were assessed. Together, these sources of variation produce an individual-level measure of mothers’ exposure to the work requirement exemptions.

DATA

The data come from the ECLS-B. The ECLS-B is a nationally representative sample of approximately 11,000 children born in 2001. The survey tracks children's early home and educational experiences by conducting detailed parent and child care provider interviews and initiating a battery of child assessments at various points between birth and kindergarten entry. The first wave of data collection occurred when focal children were nine months old (2001 to 2002), with follow-up surveys implemented at 24-months (2003), during the preschool year (2005 to 2006), and after kindergarten entry (2006 to 2007). The analysis sample comprised children from the nine-month wave. A home visit was initiated on or near the focal child's nine-month birthday to administer the cognitive assessment and to conduct a 60-minute parent interview. After applying a number of restrictions, the final analysis sample includes 8,558 children.6

To fix attention on the group of children whose mothers are potentially eligible to receive welfare, and thus likely to be influenced by states’ work requirements, I split the sample according to mothers’ educational attainment and marital status. In particular, I define the group of potentially eligible mothers as those with less than a college degree or those who are unmarried. Such definitions are fairly standard in the welfare reform literature (e.g., Bitler, Gelbach, & Hoynes, 2005; Fang & Keane, 2004; Grogger, 2003; Meyer & Rosenbaum, 2001; Schoeni & Blank, 2000). For the purposes of conducting falsification tests, I define the group of mothers ineligible to receive welfare as those with at least a college degree and those who are married. A key motivation for using educational attainment and marital status to stratify the sample is that the welfare reform literature is unsettled as to the most appropriate characteristics for identifying welfare-eligible and welfare-ineligible women. Although it is common to use both educational attainment and marital status to create the groupings (e.g., Bitler, Gelbach, & Hoynes, 2005; Hill, 2012), some studies use only education (e.g., Schoeni & Blank, 2000), while others use only marital status (e.g., Grogger, 2003; Meyer & Rosenbaum, 2001; Pingle, 2003). Relying on both characteristics therefore seems like the most comprehensive method for distinguishing between potentially eligible and ineligible families. As will be shown in a later section, changes to the sample criteria do not meaningfully change the results.

To construct these groups, one option is to use information on mothers’ educational attainment and marital status as of the nine-month assessment. However, applying these characteristics after the introduction of the policy treatment (i.e., exposure to AYCEs) would lead to a problem of endogenous sample selection if these characteristics are influenced by welfare reform. Such concerns seem warranted in light of evidence from Bitler et al. (2004) and Bitler, Gelbach, and Hoynes (2006) that welfare reform altered marriage and divorce rates as well as children's family structure. Fortunately, the ECLS-B makes available to researchers a variety of information from children's birth certificates, including the biological mother's educational attainment and marital status. Information collected at childbirth alleviates concerns over endogenous sample selection because the maternal characteristics are measured simultaneously with the initiation of the AYCE rules. Of the 8,558 children in the sample, 6,207 are included in the welfare-eligible subsample, and 2,351 are included in the noneligible subsample.

The primary outcome is a measure of children's early cognitive ability from the BSF-R test, administered at the nine- and 24-month assessments. This instrument was designed specifically for the ECLS-B and includes a subset of items from the full Bayley Scales of Infant Development—Second Edition (BSID-II), a widely accepted measure of early cognitive and motor development. Although the original BSID-II was designed to be completed in a clinical setting, the BSF-R was developed for ease of administration in a home environment. This study examines only the cognitive component of the BSF-R, containing 31 items during the nine-month assessment and 33 items during the 24-month assessment. The test measures several dimensions of early cognitive and language ability, including memory, preverbal communication, expressive and receptive vocabulary, reasoning and problem solving, and concept attainment.7 Item response theory (IRT) scale scores are used in the analysis. It is important to note that the BSID-II was used in at least one other study examining early maternal employment (Brooks-Gunn et al., 2002). In addition, it has been administered to infants in studies of the socioeconomic gradient in cognitive ability (Hanscombe et al., 2012; Rubio-Codina et al., 2015; Tucker-Drob et al., 2011), as well as the effect of early-life stress (Bergman et al., 2010; Davis & Sandman, 2010), parental time investments and interactions (Caskey, et al., 2014; McManus & Poehlman, 2012), and breast feeding (Angelsen et al., 2001) on cognitive ability.

This study examines two measures of early maternal employment. First, I test a binary indicator that equals unity if a given mother ever worked since the focal child's birth, and zero if the mother did not work since childbirth. At the nine-month assessment, mothers were asked if they worked for pay during the previous week. Among those not currently working, a follow-up question was asked whether they had done so since the focal child's birth. Children whose mothers answered affirmatively to either question were coded a value of one on this variable; all others were coded a value of zero. Approximately 58 percent of welfare-eligible mothers were ever employed since childbirth, compared to 63 percent of welfare-ineligible mothers. Second, I test a measure of cumulative employment, defined as the total number of months a given mother was employed as of the nine-month assessment. I construct this variable by combining information on the child's age and mothers’ employment status at the nine-month assessment with a survey item asking about the child's age at which the mother returned to work.8 The average welfare-eligible mother worked about 4.1 months since childbirth, only slightly less than the 4.5 months worked by the typical ineligible mother.

Figure 1 displays the evolution in maternal employment throughout the first year of the child's life. In particular, it shows the cumulative proportion of welfare-eligible and welfare-ineligible mothers who began working in each of the first 12 months following childbirth. Employment rates for both groups increase rapidly throughout the first six months of life, after which mothers’ transition into work begins to slow. Similar proportions of welfare-eligible and welfare-ineligible mothers began working within two months of childbirth (25 percent), but then the employment rates begin to diverge. By the time children are six months old, 50 percent of eligible mothers had begun working, compared to 57 percent of their ineligible counterparts. A difference is still evident at 12 months, when 57 and 63 percent of mothers had started to work, respectively.

Cumulative Maternal Employment in the First Year After Childbirth.

Source: Author's analysis of the nine-month wave of the ECLS-B.

Table 2 provides summary statistics for the subsample of welfare-eligible families. Children whose mothers did any work since childbirth scored about 1.5 points higher on the BSF-R than their counterparts whose mothers did not work. Working mothers are less likely to be high school dropouts, have fewer children, and are less likely to receive benefits from the WIC program. In addition, total annual income in households with working mothers is about 15 percent higher on average. Finally, the children of employed mothers appear to be in better baseline health: they are less likely to be classified as low birth weight and less likely to be born prematurely. These descriptive data suggest that children of working mothers are more economically advantaged than their nonworking counterparts, a pattern which may explain the test score gap in favor of the former group. The relative economic advantage of working families also highlights the central concern associated with OLS estimates of early maternal employment. In particular, working mothers are likely to be positively selected, leading to OLS estimates that are biased upward.

| Any | No | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full | maternal | maternal | |

| Variable | sample | work | work |

| Outcome | |||

| Bailey short form mental test score (BSF-R) | 74.73 | 75.38 | 73.84* |

| (10.28) | (10.11) | (10.45) | |

| Family characteristics | |||

| Mother's age at childbirth (years) | 26.54 | 26.43 | 26.68 |

| (6.03) | (5.98) | (6.09) | |

| Mother is high school dropout at childbirth | 0.254 | 0.197 | 0.331* |

| (0.435) | (0.398) | (0.471) | |

| Mother is married at childbirth | 0.573 | 0.536 | 0.623* |

| (0.495) | (0.499) | (0.485) | |

| Previous live births (no.) | 1.205 | 1.114 | 1.330* |

| (1.260) | (1.192) | (1.338) | |

| Mother used tobacco during pregnancy | 0.177 | 0.178 | 0.177 |

| (0.382) | (0.382) | (0.381) | |

| WIC participation | 0.666 | 0.648 | 0.689* |

| (0.472) | (0.478) | (0.463) | |

| English is only language spoken at home | 0.687 | 0.736 | 0.619* |

| (0.464) | (0.441) | (0.486) | |

| Household members ages 18+ (no.) | 2.226 | 2.212 | 2.244 |

| (0.912) | (0.922) | (0.897) | |

| Urban residence | 0.824 | 0.816 | 0.834* |

| (0.381) | (0.387) | (0.372) | |

| Reside in a different state | 0.034 | 0.030 | 0.039* |

| (0.180) | (0.170) | (0.193) | |

| Child characteristics | |||

| Male | 0.517 | 0.516 | 0.518 |

| (0.500) | (0.500) | (0.500) | |

| Age at assessment (months) | 10.56 | 10.61 | 10.49* |

| (1.93) | (1.95) | (1.90) | |

| Black | 0.184 | 0.211 | 0.147* |

| (0.388) | (0.408) | (0.354) | |

| Low birth weight | 0.273 | 0.257 | 0.296* |

| (0.446) | (0.437) | (0.457) | |

| Premature | 0.120 | 0.106 | 0.139* |

| (0.325) | (0.308) | (0.346) | |

| Born in first quarter of 2001 | 0.302 | 0.310 | 0.292 |

| (0.459) | (0.462) | (0.455) | |

- Source: Author's analysis of the nine-month wave of the ECLS-B.

- Notes: SDs are displayed in parentheses. All summary statistics are reported for the subsample of welfare-eligible children (i.e., children whose mothers are either unmarried or have less than a BA degree at childbirth). The column “any maternal work” refers to any employment by mothers since the birth of the focal child. Mother's age and educational attainment (i.e., high school dropout) are measured at childbirth, as recorded on the focal child's birth certificate. An asterisk (*) indicates that the null hypothesis of equal means across workers and nonworkers is rejected at the 0.10 level or better.

IDENTIFICATION STRATEGY

(1)

(1)As previously noted, a concern in the early maternal employment literature is that working and nonworking mothers may differ in ways that influence child ability. One possibility is that some mothers have skills (e.g., human capital) or personality traits (e.g., grit or motivation) that are positively correlated with labor market participation and child ability. If these characteristics are omitted from equation 1, estimates of β1 will be biased upward. On the other hand, it is conceivable that less-skilled mothers are more likely to work because they seek to offset the social and economic disadvantages that exist in the home environment. Failure to control for these characteristics would impart a downward bias on β1. The summary statistics in Table 1—establishing that working mothers are more advantaged—suggest that the net effect of the unobservables may be to bias β1 upward.

One method for dealing with this omitted variables problem is to leverage quasi-random variation in WORK through an IV. This approach will produce consistent estimates of WORK if at least one variable is found to satisfy two conditions: (i) it is highly correlated with mothers’ work decisions, and (ii) it is orthogonal to child ability except through its relationship with maternal work. This paper identifies the causal effect of early maternal employment by exploiting variation in states’ AYCEs from the work requirements. This methodology has two advantages. First, it mitigates the omitted variables problem described above. Second, constructing instruments from policies such as AYCEs allows researchers to simultaneously study the impact of policy reforms on maternal employment (via the first-stage equation) as well as important child development outcomes (via the second-stage equation).

To construct the instrument, which I denote as EXEMPT, I begin by coding each state's AYCE (in months) in 2001 (Urban Institute, 2001). These data are then merged to the analysis sample based on the child's state of residence at birth. For families residing in one of the 34 states granting the same exemption regardless of the number of previous births, EXEMPT is generated by subtracting the state's AYCE allotment from the child's age (in decimal months) at the nine-month assessment. For families residing in one of the 14 states that vary the exemption by the number of previous births, I identify the child's birth order from the birth certificate file, assign the relevant AYCE allotment to the mother, and then subtract that allotment from the child's age. Finally, for families residing in the three states providing a lifetime exemption, I take advantage of the rule that a mother cannot allocate more than a specified number of months to a single child. All three states provide a lifetime AYCE of 12 months, with two granting a maximum of three months for each child and one granting a maximum of four months. I assume that a mother takes the maximum allowable exemption for each child until the lifetime limit is reached, after which the AYCE becomes zero months for each additional child. Once the appropriate AYCE is determined, EXEMPT is calculated once again by subtracting this amount from the child's age.

Given that EXEMPT is calculated in relation to the child's age, negative values indicate that a mother has time remaining in the exemption (because the AYCE allotment exceeds the child's age), while positive values indicate that a mother exhausted the exemption (because the child's age exceeds the allotment). Variation in EXEMPT is derived from three sources. The first comes from cross-state differences in the generosity of AYCE allotments. A second source of variation comes from the birth order of focal children. Specifically, children within a given state can be assigned different values on EXEMPT depending on the AYCE that applies to their birth order. Both components are determined at the time the child is born. Thus, it is assumed that forward-looking mothers, who are provided with different stocks of exempt time, have different horizons over which to make work and welfare decisions. A smaller stock of exempt time should increase (decrease) the amount of time mothers spend working (receiving welfare) in the first year of life.

Lastly, additional within-state variation is created by virtue of the differential ages at which children were assessed (and parents reported their postbirth employment history). Although ECLS-B administrators intended to assess children when they were nine months old, in practice they were unable to accomplish this. Indeed, children were assessed between the ages of six and 22 months, although the median age-at-assessment is 10 months. This is a potentially important source of variation because children born in the same state and with the same parity will be assigned different values on EXEMPT if they happen to be assessed at different ages. It is also a plausibly exogenous source of variation because it is unlikely that parents selected an assessment date based on the child's cognitive ability (Fitzpatrick, Grissmer & Hastedt, 2011).10 This component is not determined at the time the child is born, nor is it known by mothers at what age the child will be assessed. As a result, this source of variation is not likely to be correlated with work and welfare decisions in the period proximate to the child's birth. Age-at-assessment, however, is likely to be correlated with current decisionmaking because it is assumed that mothers are aware of the child's age relative to the AYCE allotment, and they are able to estimate the remaining stock of exempt time. Together, the three sources of variation in EXEMPT—two of which are determined at childbirth and one of which is determined at the time the child is assessed—align with the measure of early maternal employment, which commingles information on mothers’ work history with that on their current work status.

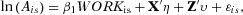

For the sample of welfare-eligible families, the median on EXEMPT is 5.4 months (SD = 6.9), with a minimum of −16.8 and a maximum of 21.8, indicating that the typical welfare-eligible mother had exhausted the AYCE by over five months at the nine-month assessment. Figure 2 presents a richer picture of the variation in EXEMPT. Again using welfare-eligible families, I plot in descending order the median number of months remaining in families’ exemption, aggregated to the state-level. For presentation purposes, the figure is constrained to families in the 15 states with the largest (Texas to West Virginia) and smallest (Washington to Idaho) median AYCE allotment. It is clear that substantial variation exists in EXEMPT: at the nine-month assessment, the median family in Texas and Massachusetts had approximately 14 months remaining in its AYCE from the work requirements, while that in Maryland and Idaho had exhausted the exemption by at least 11 months.

Remaining AYCE Allotments for Welfare-Eligible Families, by State.

Source: Author's analysis of the nine-month wave of the ECLS-B.

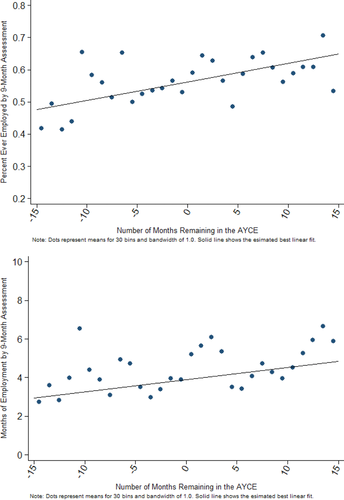

To check whether the first identifying condition holds, I provide graphical and regression-based evidence on the first-stage relationship between EXEMPT and early maternal employment. Appendix Figures C1a and b display raw (unconditional) results for the binary indicator of any maternal employment and the measure of cumulative employment, respectively.11 Each dot represents the unadjusted mean maternal employment rate within one-month bandwidths of EXEMPT.12 The solid line shows the estimated best linear fit. Both figures reveal a strong relationship between the work requirement exemption and first-year maternal employment: rates of work participation and months of work are greater among mothers facing shorter AYCEs.

(2)

(2)| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Welfare eligible subsample | |||

| EXEMPT | 0.0057*** | 0.0384*** | −0.0016*** |

| (0.0010) | (0.0078) | (0.0005) | |

| F-statistic (P-value) | 31.00 | 24.48 | NA |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Panel B: Ineligible subsample | |||

| EXEMPT | 0.0024 | 0.0188 | −0.0001 |

| (0.0021) | (0.0154) | (0.0004) | |

| F-statistic (P-value) | 1.25 | 1.49 | NA |

| (0.282) | (0.242) | ||

| P-value: test of coefficient differences | 0.058 | 0.293 | 0.021 |

| Family characteristics | Y | Y | Y |

| Child characteristics | Y | Y | Y |

| Region dummies | Y | Y | Y |

| State characteristics | Y | Y | Y |

| Dependent variable | Any work | Months of work | TANF receipt |

| Number of observations | 6,207/2,351 | 6,172/2,338 | 6,203/2,349 |

- Source: Author's analysis of the nine-month wave of the ECLS-B.

- Notes: Standard errors are displayed in parentheses and are adjusted for clustering within date of assessment cells. The dependent variable in 1 is the binary indicator for any maternal employment as of the nine-month assessment. The dependent variable in 2 is the measure of cumulative employment, defined as the number of months of employment as of the nine-month assessment. The dependent variable in (3) is a binary indicator for welfare receipt since the focal child was born. The family characteristics are noted in the text under equation 1. All models include region of birth indicators as well as 22 state-level controls. See text under equation 1 for a list of the state controls. ***, **, * indicate statistical significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

Columns 1 and 2 provide evidence of a strong first-stage relationship between EXEMPT and WORK. Increases in EXEMPT—representing reductions in the remaining AYCE allotment—are positively associated with the likelihood that mothers engage in any work as well as cumulative months of work. A one-month reduction in the AYCE increases the likelihood of employment by 0.6 percentage points—panel A, column 1—and increases months of employment by 0.04 months—panel A, column 2. With F-statistics of 31 and 25, respectively, EXEMPT easily exceeds the rule of thumb cut-off for a weak instrument (F-statistic = 10) formalized by Staiger and Stock (1997). Results in panel B provide a falsification test by estimating the first-stage equation on the subsample of welfare-ineligible families. If EXEMPT does in fact capture mothers’ exposure to AYCEs, then one would expect EXEMPT to be unrelated to the work decisions of mothers not at risk of receiving welfare. Results in columns 1 and 2 suggest that EXEMPT passes the falsification test: the coefficients are substantially smaller in magnitude, and neither is statistically significant. As shown in the last row, tests of the differential effect of EXEMPT across groups of eligible and ineligible families reveal a statistically significant difference for the measure of any work, but not for cumulative work.

The model in column (3) provides an additional robustness check. The dependent variable is a binary indicator equal to unity if a given family received cash assistance at any point since the child's birth. The expectation is that reductions in the AYCE allotment should reduce the likelihood of receiving welfare in the eligible subsample, while having no effect on participation in the ineligible subsample. Both predictions are borne out. Specifically, the coefficient in the welfare-eligible subsample implies that a one-month reduction in the exemption reduces the likelihood of receiving welfare by 0.2 percentage points, a result that is statistically significant. Meanwhile, the coefficient in the subsample of ineligible families implies a substantially smaller and imprecisely estimated reduction in welfare receipt. In addition, the test of a differential effect of EXEMPT across eligible and ineligible families is statistically significant.

To serve as a valid instrument, EXEMPT must also fulfill the second identifying assumption—that it is appropriately excluded from the child's test score equation—which cannot be tested directly. Nevertheless, there are a few apparent concerns with using AYCEs as an instrument for maternal employment. First, variation in EXEMPT is generated in part from a number of child characteristics, specifically birth order and age-at-assessment. It is conceivable that both characteristics are related to mothers’ work decisions and child well-being. A related issue is the potential endogeneity of fertility decisions, in which unobserved maternal characteristics are related to the number and timing of births. I deal with these complications by including in X explicit controls for the child's age at the nine-month assessment, entered in decimal months and a quadratic in months, as well as a full set of birth order fixed effects.

Given that one source of variation in EXEMPT is the cross-state differences in AYCE allotments, another concern is a type of policy endogeneity in which these exemptions are correlated with other state-level social policy, economic or demographic characteristics that influence child ability. Of particular concern is the potential correlation of AYCEs with other features of welfare reform. For example, political decisions regarding the generosity of work requirement exemptions could be related to the stringency of benefit sanctions or time limits. In addition, it is possible that states with more favorable economic conditions provide less generous AYCE allotments. If these unobserved state characteristics are correlated with child ability, then EXEMPT would be an invalid instrument.

I attempt to handle policy endogeneity by incorporating in the baseline model a set of region of birth indicators as well as 22 state-level controls that capture several dimensions of states’ social policy, economic, demographic, and political environment (listed in footnote 9).13 Some may argue that state fixed effects are more robust controls for policy endogeneity. In this context, however, fixed effects may not be appropriate. Since variation in EXEMPT is derived in part from cross-state differences in AYCE provisions, it is not surprising that the fixed effects explain much of its variation. Indeed, the R2 from a regression of EXEMPT on the state of birth fixed effects is 0.81. Including fixed effects therefore leaves little variation in the instrument to identify WORK in the second-stage equation. In contrast, the R2 from a regression of EXEMPT on the region of birth indicators and 22 state-level controls is 0.45. Furthermore, although the fixed effects are highly correlated with EXEMPT, excluding them would induce bias only if they are systematically related to cross-state differences in child ability, conditional on the observable controls. The state-fixed effects do not appear to be strongly correlated with child cognitive ability. In a regression of the nine-month BSF-R score on the state-of-birth fixed effects, the state indicators explain only 6 percent of the variation in test scores. Furthermore, the incremental R2 associated with adding the fixed effects (to a model that includes the family and child controls) is 1.3 percent. Importantly, the fixed effects do not meaningfully outperform the region indicators and state-level controls: the incremental R2 associated with these controls is 0.8 percent.14

ESTIMATION RESULTS

Baseline OLS and IV Estimates

Table 4 presents the main OLS and IV estimates for the impact of early maternal employment on children's BSF-R scores. Columns 1 and 2 provide the OLS results for the binary indicator of any work and the measure of cumulative work, respectively. Column (3) displays the reduced form results, in which children's BSF-R scores are regressed on EXEMPT. Columns (4) and (5) show the IV estimates on both maternal employment measures. Panel A provides these results for the welfare-eligible subsample, and, as a robustness check, panel B provides them for the ineligible subsample.

| OLS-1 | OLS-2 | Reduced form | IV-1 | IV-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Panel A: Welfare-eligible subsample | |||||

| WORK/EXEMPT | 0.0061*** | 0.0006*** | −0.0004* | −0.0684** | −0.0103* |

| (0.0010) | (0.0001) | (0.0002) | (0.0344) | (0.0060) | |

| Panel B: Ineligible subsample | |||||

| WORK/EXEMPT | 0.0043 | 0.0005 | 0.0002 | 0.0648 | 0.0064 |

| (0.0052) | (0.0006) | (0.0003) | (0.1524) | (0.0182) | |

| Family characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Child characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Region dummies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| State characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Number of observations | 6,207/2,351 | 6,172/2,338 | 6,207/2,351 | 6,207/2,351 | 6,172/2,338 |

- Source: Author's analysis of the nine-month wave of the ECLS-B.

- Notes: Standard errors are displayed in parentheses and are adjusted for clustering within date of assessment cells. WORK in 1 and (4) is the binary indicator for any maternal employment. WORK in 2 and (5) is cumulative employment. ***, **, * indicate statistical significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

Regarding the OLS results in panel A, the evidence points to a positive relationship between early maternal employment and children's test scores. The coefficient on WORK in column 1 implies that any maternal employment since childbirth is associated with a 0.6 percent increase in BSF-R scores, while the coefficient in column 2 implies that an additional month of work increases test scores by 0.06 percent. Both estimates are highly statistically significant. Turning to the OLS results for the ineligible subsample, shown in panel B, it appears that early maternal work does not influence the test scores of economically advantaged children. The magnitudes of both coefficients are smaller than their counterparts in panel A, and neither coefficient is statistically significant.

The reduced form estimate in panel A is negative and statistically significant, indicating that reductions in the AYCE time allotment are associated with lower test scores. Specifically, a one-month reduction in the AYCE reduces BSF-R scores by 0.04 percent. This result is interesting in its own right because it illustrates the relationship between an important public policy lever and child ability. This can be interpreted as an intent-to-treat estimate of AYCEs, in that it averages the effect of work requirement exemptions over mothers who did and did not change their work behavior because of the exemption. The falsification test, shown in panel B, indicates that, as expected, AYCEs are not associated with the BSF-R scores of children in welfare-ineligible families. In fact, the coefficient on EXEMPT is half as large as and takes the opposite sign from that based on the welfare-eligible subsample.

The remaining columns in Table 4 provide the baseline IV estimates of the impact of early maternal employment. These estimates are interpreted as the local average treatment effect (LATE) of maternal employment, because it reveals the effect of employment on the subset of mothers who altered their work behavior in response to the work requirement exemption. Given the positive coefficient on EXEMPT in the first-stage equation and its negative coefficient in the reduced form equation, it is not surprising that panel A's IV estimates on WORK are negative (and statistically significant). Looking at column (4), the coefficient suggests that any maternal work since childbirth reduces BSF-R scores by 6.8 percent. The IV estimate on cumulative months of maternal work is also negative, implying that an additional month of work lowers test scores by 1 percent. This corresponds to an effect size of 0.08 SDs.15

The results in panel B—based on a sample of families ineligible for welfare—provide evidence in favor of the validity of the identification strategy. In particular, the coefficient on EXEMPT in the reduced form equation (column 3) takes the opposite sign from its counterpart in panel A and is not statistically significant. Given the lack of explanatory power on EXEMPT in the first-stage equation, one might expect the IV estimates on WORK to be statistically insignificant. As shown in columns (4) and (5), the IV standard errors are substantially larger than their counterparts in panel A, leading to highly imprecise estimates. In addition, the coefficients take the opposite sign compared to those based on the welfare-eligible subsample.

In estimations not presented in the table, I also examine a number of subgroups, whose results are available upon request. I find little evidence that boys and girls are differentially affected by early maternal employment. Second, I examine nonminority (i.e., white) and minority (i.e., black and Hispanic) children. Here, I find meaningful differences. Any first-year employment reduces BSF-R scores among white children by 14.4 percent, compared to a 4.2 percent decrease among black and Hispanic children. Next, I examine whether severely disadvantaged children are more sensitive to early maternal work, using children's low birth weight status as a proxy for disadvantage. The results indicate that maternal work may exacerbate the disadvantages associated with low birth weight. Any first-year employment lowers BSF-R scores by 24.1 percent among low birth weight children, compared to a 3.2 percent reduction among normal weight children. Finally, I examine whether mothers’ prebirth employment status has implications for the impact of postbirth employment. It is possible that women with prebirth work experience sustain fewer family disruptions and find it easier to transition back into the labor market than their counterparts without prebirth work experience. The IV results are suggestive of such a pattern. The impact of any first-year employment is associated with larger negative effects on children whose mothers did not work prior to childbirth (11.2 percent) than those who did work (7.4 percent).

ROBUSTNESS

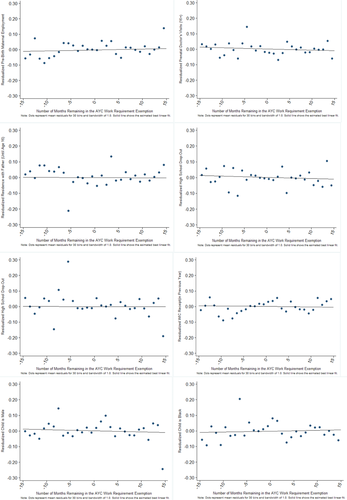

Appendix Table C3 provides an additional set of specification checks.16 Estimates in rows 1 and 2 are derived from alternative IVs. The sample in row 1 is limited to children born in states with a birth order or lifetime AYCE. This approach has two advantages. First, variation in EXEMPT is produced exclusively by the child's birth order and age-at-assessment, which are arguably more valid sources of variation than the cross-state variation included in the full version of EXEMPT. Second, the AYCEs for these states are (fortuitously) identical to one another. Thus, policy endogeneity is no longer a problem. The obvious drawback is the large loss of observations. That both IV estimates on WORK are no longer statistically significant is a testament to the smaller sample size. Nevertheless, they remain similar to the baseline results. Row 2 relies on an IV that uses only the state of residence and the child's birth order to calculate the AYCE. In other words, the IV eschews the child's age-at-assessment and simply assigns the number of months in each state's exemption from the work requirement. This version of the IV represents a check on the influence of children's age on generating the IV estimates. Estimates from these models are quite similar to those in the baseline models, and the coefficient in the model for any work remains statistically significant. Together, the estimates in rows 1 and 2 lend further support to the validity of EXEMPT.

Rows (3) through (5) test the sensitivity of the baseline estimates to the omission of groups of control variables. This exercise further assesses the validity of EXEMPT: if EXEMPT generates exogenous changes in early maternal employment, then the IV estimates should not be highly sensitive to the exclusion of basic demographic controls. Row (3) omits the full set of family controls (except birth order), row (4) omits the full set of child controls (except child age), and row (5) omits both sets of controls. The point estimates on WORK are consistently similar to the baseline estimates, but the standard errors tend to be larger. This indicates that the observable covariates are important not to maintain the exogeneity of EXEMPT, but rather to increase the efficiency of the IV estimates. Such results provide additional support for the validity of the IV strategy.

The next three rows—rows (6) through (8)—experiment with richer sets of maternal characteristics. As previously stated, the baseline model includes a dummy variable for families residing in states with more generous parental leave provisions than the FMLA. This control allays concerns over the possibility that states’ AYCEs are correlated with other parental leave policies. As a further check, row (6) includes a control for mothers taking leave before or after childbirth. Another concern is that WORK might be correlated with prebirth employment, thus biasing the IV estimates if prebirth employment influences child ability. Row (7) adds a dummy variable that controls for prebirth maternal employment. Row (8) includes four additional maternal background controls: separate controls for whether the mother lived with her biological mother and father until age 16 and separate controls for whether the mother's biological mother and father were high school dropouts. Accounting for these maternal characteristics does not change the baseline IV estimates.

It was shown earlier that EXEMPT is associated not just with increased work participation, but also with reductions in TANF participation. The loss of welfare income is therefore one potential explanation for the negative IV estimates. I test this possibility by including a variable capturing the number of months a given family received TANF since childbirth. As shown in row (9), the IV estimates are similar in magnitude to the baseline estimates, suggesting that work-requirement-induced changes in welfare participation are not driving the negative effect of early maternal work.

In addition to granting child-age exemptions from the work requirements, states may exempt women for a variety of other reasons. For example, 34 states exempt women caring for an ill or incapacitated family member, and 20 states exempt pregnant women. It is plausible that state decisionmaking regarding the generosity of AYCEs is correlated with decisions on whether to exempt other categories of women. The estimates in row (10) add separate controls denoting these alternative work requirement exemptions. The IV estimates are similar to the baseline estimates; if anything the results imply somewhat larger negative effects of early maternal employment.

Recall that the baseline estimates are generated from a sample of children born to mothers with less than a college degree or who are unmarried. Results in the next two rows alter the definition of the analysis sample. Row (11) removes the marital status criterion, so that educational attainment is the sole maternal characteristic for delineating the sample. The IV results based on this alternative sample definition are similar to the baseline estimates. Row (12) establishes more narrow criteria by including children born to mothers with no more than a high school degree and who are unmarried. The point estimates are similar to the baselines estimates, although neither is statistically significant because the standard errors are substantially larger. One reason for this is that the narrower definition reduces the sample size by about two-thirds relative to the baseline sample.

Timing of the Maternal Return to Work

The results discussed so far suggest that work requirement-induced entries into employment during the first year of life have negative effects on children's cognitive development. It is possible that heterogeneity exists according to the timing of the return to work within the first year. Previous research finds that earlier returns have larger negative effects than later returns, although some of this work compares first-year employment with that occurring in the second and third years of life (e.g., Ruhm, 2004). Han, Waldfogel, and Brooks-Gunn (2001) examine heterogeneity within the first year by comparing the impact of beginning work within the first three quarters after childbirth versus beginning work in the fourth quarter. Here, again, the authors find larger negative effects of earlier returns to work.

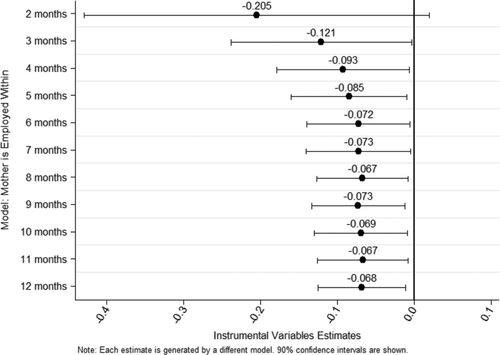

I examine heterogeneity throughout the first year of life by using EXEMPT to instrument for a series of dummy variables indicating the age (of the child) at which the mother began working. Specifically, I construct 11 binary indicators for whether the mother was employed within the first two months after childbirth, within the first three months, and so on up to 12 months. I then estimate separate IV models using EXEMPT as an instrument for each month-of-work indicator. Results from this analysis are summarized in Figure 3, which plots the IV coefficient from each month-of-work model along with the upper and lower bounds of the 90 percent confidence interval.17

A few observations are noteworthy. First, maternal returns to work—no matter when they occur during the first year of life—have negative effects on children's cognitive development. All of the month-of-work indicators are negatively signed, and all but one are statistically significant at the 10 percent level. Nevertheless, there is substantial variation in the estimates, ranging from a 20 percent reduction in BSF-R scores (for children of mothers who worked within two months) to a 6.7 percent reduction in scores (for children of mothers who worked within 11 months). In addition, consistent with previous work, later returns to work generate smaller reductions in test scores, but only up to a point. The magnitude of the (negative) test score effect declines in each subsequent month-of-entry until about the eighth month of life, after which the negative effects stabilize. Indeed, starting work at some point in the fourth quarter of life produces substantially smaller and more stable test score effects than doing so in the first or second quarters of life.

Mechanisms

This section examines several mechanisms through which welfare work requirements may influence child ability. Table 5 organizes these mechanisms around nine-month family income and material resources, maternal health, parent-child interactions and parental time investments, and participation in nonparental child care. Column 1 presents the mean on each measure. Column 2 presents the reduced form estimate on EXEMPT, while columns (3) and (4) present the IV estimates on WORK.

| Mean | Reduced form | IV-1 | IV-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 1. Household income below FPL | 0.326 | −0.0019** | −0.3214*** | −0.0492** |

| (0.469) | (0.0008) | (0.1251) | (0.0196) | |

| 2. Maternal health “excellent” or “very good” | 0.609 | 0.0001 | 0.0086 | 0.0069 |

| (0.488) | (0.0013) | (0.2155) | (0.0342) | |

| 3. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | 5.629 | 0.0119 | 1.980 | 0.2670 |

| (5.742) | (0.0127) | (1.798) | (0.2866) | |

| 4. Mother felt depressed at least one day last week | 0.337 | 0.0023* | 0.3666** | 0.0530* |

| (0.473) | (0.0012) | (0.1791) | (0.0321) | |

| 5. Child was breast fed | 0.616 | −0.0023* | −0.4014* | −0.0634* |

| (0.486) | (0.0013) | (0.2179) | (0.0340) | |

| 6. Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) | 33.84 | 0.0133 | 2.2252 | 0.3491 |

| (4.51) | (0.0133) | (2.2200) | (0.3220) | |

| 7. Child demands constant attention/needs much help sleeping | 0.293 | 0.0025* | 0.4326* | 0.0621* |

| (0.455) | (0.0012) | (0.2280) | (0.0333) | |

| 8. Family member reads to child at least once per week | 0.846 | −0.0019* | −0.3280** | −0.0553* |

| (0.361) | (0.0010) | (0.1676) | (0.0315) | |

| 9. Cumulative number of months in nonparental child care | 3.336 | 0.0189* | 3.2796** | 0.4519* |

| (3.915) | (0.0107) | (1.4122) | (0.2374) | |

| 10. Weekly hours spent in all nonparental child care arrangements | 14.68 | 0.0858* | 14.669*** | 2.181** |

| (20.21) | (0.0447) | (5.557) | (0.889) | |

| 11. Child uses nonparental child care in first three months after birth | 0.301 | 0.0033*** | 0.5691*** | 0.0781*** |

| (0.459) | (0.0011) | (0.1761) | (0.0224) | |

| 12. Child uses relative care | 0.327 | 0.0019 | 0.3652 | 0.0577 |

| (0.469) | (0.0017) | (0.2685) | (0.0529) | |

| 13. Child uses nonrelative care | 0.177 | 0.0029* | 0.5348*** | 0.0843** |

| (0.381) | (0.0017) | (0.2058) | (0.0371) | |

| 14. Child uses center-based care | 0.103 | −0.0006 | −0.1859 | −0.0340 |

| (0.304) | (0.0013) | (0.3918) | (0.0905) |

- Source: Author's analysis of the nine-month wave of the ECLS-B.

- Notes: SDs in column 1 are displayed in parentheses. For columns 2 through (4), standard errors are displayed in parentheses and are adjusted for clustering within date of assessment cells. WORK in (3) is the binary indicator for any maternal employment. WORK in (4) is cumulative employment. Variable definitions, by row number, are 1 binary indicator for families below the Federal Poverty Line (FPL), 2 binary indicator for mothers in excellent or very good overall health, (3) mother's score on the CES-D depression scale, (4) binary indicator for mothers who “felt depressed” at least one day during the past week, (5) binary indicating for children who were breast fed since child birth, (6) mother's score on the NCATS scale, (7) binary indicator for children who “sometimes” or “most times” “demands attention and company constantly” and “needs a lot of help to fall asleep,” (8) binary indicator if the child is read to by a family member at least one time per week, (9) cumulative number of months the child spends in nonparental care, (10) total number of hours per week the child spends in all nonparental arrangements, (11) binary indicator for children who began a nonparental arrangement in the first three years of life, and (12) through (14) binary indicators for the child's participation in relative, nonrelative, and center-based child care arrangements at nine months. ***, **, * indicate statistical significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

A number of studies find that family income is strongly related to early and later child development (e.g., Blau, 1999; Dahl & Lochner, 2012). Increases in family income likely improve parental and child physical and mental health, and enable parents to invest in goods and services that promote child ability. Thus, the first mechanism relates to family income—row 1. Although the ECLS-B does not contain a high-quality measure of family income, the survey provides an indicator denoting whether family income is below the Federal Poverty Line (FPL). As shown in column 1, a large fraction of welfare-eligible children reside in poor families (33 percent). The reduced form estimate on EXEMPT implies that reductions in the AYCE time allotment are associated with lower poverty rates. This finding is consistent with the IV results, in which maternal employment decreases the likelihood of falling below the FPL.

Although these results appear to be at odds with the IV estimates, a few caveats should be mentioned. First, it is possible that the income required to bring a family above the FPL is not sufficient to improve the child's cognitive ability. Second, the FPL measure is based on current rather than permanent income, with the latter shown to be more important to child ability. Finally, family income is the only mechanism that yields a result consistent with an improvement in child ability.

The next three rows investigate mechanisms related to mothers’ health. Row 2 shows that early maternal work does not influence overall health, defined as self-reports of health as excellent or very good (as opposed to good, fair, or poor). However, it appears that maternal employment may increase depression symptomology, as measured by the 12-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Rossin, 1977).18 The IV estimates on the full CES-D (row [3]) imply substantively meaningful, but imprecisely estimated, increases in depression symptomology. Row (4) recodes one of the items into a binary indicator that equals unity if a given mother felt depressed during one or more days throughout the previous week. Here, the IV estimates indicate that maternal work leads to statistically significant increases in depressive symptoms.

The next four analyses examine the mother-child relationship. Row (5) explores whether early maternal employment influences breast feeding. A large literature finds that breast feeding is associated with short- and long-run physiological, health, and cognitive benefits (e.g., Horwood & Fergusson, 1998). Previous studies also find that early maternal employment can disrupt breast feeding practices (Lindberg, 1996), and at least one study indicates that welfare reform lowered rates of breast feeding (Haider, Jacknowitz, & Schoeni, 2003). The reduced form and IV results, which show substantial reductions in breast feeding, are consistent with this evidence. Row (6) examines maternal scores on the Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS), a 50-item measure of various domains of parent-child interactions.19 The IV estimates are small in magnitude and statistically insignificant. Row (7) explores maternal views regarding the child's temperament and attachment. I create separate binary indicators that equal unity if a mother reports that the child “demands attention and company constantly” or “needs a lot of help to fall asleep.”20 The results suggest that working mothers are more likely to respond affirmatively to these statements. Finally, row (8) examines the frequency with which mothers read to the child. I create a binary indicator that equals unity if a family member reads to the child at least once per week. The estimates indicate that maternal employment reduces the likelihood that the child is read to on a consistent basis.

The final set of analyses examines the extent to which maternal employment influences the use of nonparental child care. There is a large literature in economics and developmental psychology studying the relationship between child care utilization and child development. Although the literature is mixed overall, a few recent studies provide causal evidence that child care participation lowers cognitive ability test scores among disadvantaged children (Bernal & Keane, 2011; Herbst, 2013). Results in rows (9) through (11) indicate that the infants of employed mothers are more likely to have started their first child care spell within the first three months of life, accrue more months in nonparental arrangements throughout the first year, and spend considerably more hours per week in these settings. The final set of analyses—rows (12) through (14)—examines the type of child care used.21 I find that children of working mothers are more likely to enter informal arrangements (i.e., nonrelative care) and less likely to enter formal arrangements (i.e., center-based care). This pattern suggests that families turn to logistically and financially accessible forms of child care in order to meet the work requirements. These results are also consistent with recent work showing that informal child care settings may have negative effects on early test scores, while formal settings have neutral or even positive effects (Bernal & Keane, 2011; Herbst, 2013).

Persistence

The final set of analyses, presented in Table 6, examines the longer run impact of early maternal employment. I draw on the ECLS-B's 24- and 60-month surveys, in which children were administered the BSF-R again (24 months) as well as language/literacy, math, and teacher-reported behavior assessments (60 months). Previous work shows that early maternal employment may have persistent adverse effects on cognitive and behavioral outcomes. For example, Ruhm (2004) finds that first-year employment has negative effects on the verbal ability of three- and four-year olds, while Han, Waldfogel, and Brooks-Gunn (2001) and Waldfogel, Han, & Brooks-Gunn, (2002) find negative effects on the verbal and math ability of seven- and eight-year olds, as well as increases in externalizing behavior at ages seven and eight.

| Reduced Form | IV-1 | IV-2 | IV-1 | IV-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| BSF-R score at 24 months | −0.0006** | −0.1367** | −0.0113*** | −0.1789** | −0.0135*** |

| (0.0003) | (0.0581) | (0.0041) | (0.0710) | (0.0047) | |

| Language/literacy score | 0.0004 | 0.0505 | 0.0044 | 0.0297 | 0.0030 |

| at 60 months | (0.0007) | (0.1034) | (0.0068) | (0.1267) | (0.0076) |

| Mathematics score | −0.0006 | −0.0943 | −0.0056 | −0.1379 | −0.0076 |

| at 60 months | (0.0008) | (0.1045) | (0.0072) | (0.1436) | (0.0087) |

| Externalizing behavior | 0.0028 | 0.4762 | 0.0308 | 0.5837 | 0.0329 |

| at 60 months | (0.0036) | (0.5501) | (0.0354) | (0.7285) | (0.0396) |

| Prosocial behavior | −0.0006 | −0.1021 | −0.0036 | −0.1083 | −0.0028 |

| at 60 months | (0.0029) | (0.4591) | (0.0292) | (0.6024) | (0.0333) |

| Approaches to learning | 0.0028 | 0.4659 | 0.0297 | 0.5904 | 0.0326 |

| at 60 months | (0.0030) | (0.4647) | (0.0273) | (0.6665) | (0.0319) |

| Child is unhappy | 0.0040 | 0.6189 | 0.0387 | 0.8206 | 0.0452 |

| at 60 months | (0.0038) | (0.5861) | (0.0375) | (0.7880) | (0.0430) |

| Child worries about things | 0.0040 | 0.6579 | 0.0416 | 0.8724 | 0.0481 |

| at 60 months | (0.0037) | (0.6470) | (0.0362) | (0.9522) | (0.0430) |

| Child acts shy at 60 months | 0.0010 | 0.1748 | 0.0111 | 0.2950 | 0.0158 |

| (0.0049) | (0.7651) | (0.0464) | (1.024) | (0.0535) | |

| Contemporaneous maternal employment | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Family characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Child characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Region dummies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| State characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

- Source: Author's analysis of the 9-, 24-, and 60-month waves of the ECLS-B.

- Notes: Standard errors are displayed in parentheses and are adjusted for clustering within date of assessment cells. WORK in 2 and (4) is the binary indicator for any maternal employment. WORK in (3) and (5) is cumulative employment. All models include a control for the lagged outcome. Models in (4) and (5) include a control for contemporaneous maternal employment (i.e., at 24- or 60-months). ***, **, * indicate statistical significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

The estimation of longer run outcomes must grapple with a thorny econometric issue. Although the goal is to estimate the causal effect of first-year maternal employment, doing so is complicated by the possibility that maternal employment at 24 and 60 months may independently affect children's outcomes at these ages. Two options are available to handle this complication. One is to omit from the model controls for maternal employment at these later ages. However, doing so may bias the IV estimates on WORK if first-year maternal employment is correlated with employment measured at 24 and 60 months. In other words, the IV estimates might reflect the commingled effect of early and later employment. The other option is to include controls for later maternal employment. This option is not ideal because these variables are also endogenous, and additional instruments are not available (the baseline IV model is just identified).

The approach taken here is to estimate the IV model both with and without controls for later maternal employment. Specifically, in some models of 24 month BSF-R scores I include a dummy variable that equals unity if a given mother was employed at the 24-month assessment. The analogous control is included in some models examining the 60-month outcomes. All models also include lags of the outcomes to account for difficult-to-measure parental investments in child quality that may influence mothers’ later work decisions. Column 1 provides the reduced form estimates; columns 2 and (3) provide the IV estimates without controlling for later maternal employment; and columns (4) and (5) include these measures.

Looking first at the results for the 24-month BSF-R, the reduced form estimate continues to show a negative relationship between AYCEs and cognitive ability. This negative effect is also reflected in the IV models. Indeed, the coefficient in column 2 implies a statistically significant 14 percent reduction in test scores given any maternal work in the first year, while that in column (3) implies a statistically significant 1.1 percent reduction for each additional month of work. As shown in columns (4) and (5), the IV estimates are robust to the inclusion of a control for 24-month maternal employment.

The next two rows examine cognitive outcomes measured at 60 months. The ECLS-B administered at kindergarten entry a language and literacy test aimed at assessing prereading and vocabulary skills, as well as a mathematics test aimed at assessing numerical and spatial ability. Although the estimates imply an increase in language skills and a reduction in math skills, none of the coefficients are statistically significant. The final set of rows examines a variety of teacher-reported behavior outcomes: a seven-item measure of externalizing (i.e., aggressive and impulsive) behavior, a six-item measure of prosocial (i.e., friendly and empathic) behavior, a six-item measure of approaches to learning (i.e., attentiveness and focus), and single-item measures of children's happiness, worrying, and shyness. Each item is measured on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating a greater frequency of negative behaviors. There is fairly consistent evidence that early maternal work leads to a worsening of behavior, as well as increases in unhappiness and worrying, but none of the coefficients are statistically significant. Together, the evidence in Table 6 indicates that the negative effect of first-year maternal employment persists to the second year of life, but there is insufficient evidence to conclude that it persists to kindergarten entry.

CONCLUSION