Mens rea, wrongdoing and digital advocacy in social media: Exploring quasi-legal narratives during #deleteuber boycott

Funding information: Fundación BBVA

Abstract

#Boycotts represent digital advocacy attempts in which users publicly punish an organization as a lurata (i.e., jury), which assesses the guilty intent, the mens rea (i.e., guilty mind), from a set of visible acts, the actus reus (i.e., wrongdoings). Yet, we know little about the quasi-legal narratives advocated by users. To this aim, we developed a mixed method study of the #deleteuber boycott on Twitter. Our findings suggest that while users advocate both an Uber-specific and a shared mens rea of Uber with sharing economy firms or the tech giants of Silicon Valley, the latter narrative is the most prominent one; its use depends on whether users are part of a lurata of influencers or not. These findings provide a contribution to studies on public affairs that focus on online activism, boycotts in social media and digital advocacy because they increase our understanding of the opaque legal motivations that provoke boycotters. Also, they highlight that social media blurs the boundaries between boycotts directed at the firm from the boycotts arising indirectly due to the shameful acts of the industry or peers.

1 INTRODUCTION

“If Uber's Culture Is to Change, the CEO Must Go #recruitment #wearefunction” (tweet #2164)

“Uber has a sexism problem, and so does Silicon Valley” (tweet #2224)

“Taxi convoy now at Parliament as drivers protest, Uber regulation industry reform introduced in Vic. #sharingeconomy” (tweet #1848)

The quotations above exemplify different narratives used during the #deleteuber boycott advocating that Uber is a bad company and deserves to be sanctioned. The first argues that Uber has a toxic culture because of its CEO. The second asserts that Uber is bad because it promotes the sexist culture that is typical of other Silicon Valley technological giants. And the third stresses that Uber being part of the sharing economy is seen as unregulated unlike the taxi services. Though at first glance these narratives may represent similar advocating message strategies against Uber with regards to different sort of organizational misconducts (Roulet, 2020), in reality, they attribute nuanced quasi-legal perspective, as they discuss slightly different levels of mens rea of Uber, namely an organization-specific means rea, and a shared mens rea among firms that belong to the sharing economy or technological giants of the Silicon Valley.

Mens rea (Alicke, 2000; LaFave, 2000) is a concept that comes from criminal law (Gardner, 1993). It refers to the following principle: “actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea” (an act does not make one guilty unless his mind is guilty) (Gardner, 1993, p. 636). It derives that when a narrative about an organizational wrongdoing emerges there are typically two stories (Godfrey et al., 2009): one about the egregiousness of the actus reus (i.e., the guilty act), and the second about the gravity of mens rea (i.e., the guilty mind or intent behind the act). The latter is typically paired with the gravity of the punishment that the organization receives. The guilty intent suggests that the actor “intended, knew and should have known when (he) acted” (Rosenfield, 2008, p. 1842). Also, a mens rea attracts not only disapproval but also stigma associated with criminality (Roulet, 2020).

Extant research on boycotts (e.g., Balabanis, 2013; Hon, 2015; Ibrahim, 2019; Kang, 2012; Kanol & Nat, 2017; Liew et al., 2013; Makarem & Haeran, 2016) has primarily focused on analyzing how boycotters (digitally) advocate for a narrative related to actus reus. Few studies have analyzed the narrative of the equally important mens rea. This is surprising since the evaluation of a mens rea constitutes the core of a boycott given that users carry out an evaluation akin to that of a trial jury in court (Balabanis, 2013): that is, the more the company displays a mens rea in a misconduct, the more it is likely to be put in the public pillory. Balabanis (2013) points to a further nuance in that those boycotters initiating an indirect boycott may advocate not only for an organization-specific mens rea (i.e., the organization should have known it was wrong but did it), but also for a shared-mens rea (i.e., the company should have known it was wrong as others in the industry are disapproved for this, but did it). A third and important element in the link between an actus reus and the boycott is the role of the boycotter. It is the public jury, the lurata, that infers the mens rea from the actus reus. The lurata is influenced by public opinion, public discourse and their own reference points. Therefore, it is likely that differences in the lurata can affect how they attribute mens rea and which actus reus they consider graver in their mental calculus.

Given that the narrative of mens rea has been relatively unexplored yet play a crucial role is social advocacy, we develop a study about the rather quasi-legal motivation of boycotters, in particular their narrative with regards to the guilty act in committing a misconduct. Specifically, How is mens rea digitally advocated during a boycott? Do boycotters advocate for an organization-specific mens rea, a shared mens rea, or both? Are boycotters homogenous or is there variety here?

Extant research in public affairs that focus on online activism suggests that the disruptive impact of boycotts has been amplified by the diffusion of digital networks. Online, boycotters can easily organize and mobilize masses against corporate misbehavior (Den Hond & De Bakker, 2007; Illia, 2003; Shah et al., 2019; Yuksel et al., 2019). Not only does social media enable new forms of political advocacy (Figenschou & Fredheim, 2019) but also allow potentially anybody to exert a certain level of social control (Barclay et al., 2011) on corporations through community-building. That is, anybody—not just a consumer association or an NGO—may mobilize masses that shame organizations and punish the company publicly. This democratization of justice via an online public jury adopting quasi-legal narratives becomes even more significant considering various new business models, such as that of sharing economy, function in a regulatory limbo and thus may not be within the jurisdiction of a purely legal regulator (Brady et al., 2015; Kanol & Nat, 2017). This has given birth to a new type of digital advocacy further enabled by the rise of social networks (Den Hond & De Bakker, 2007), that can be defined as “an (act of) organized public effort, (…) in which civic initiators or supporters use digital media” (Edwards et al., 2013).

We draw on extant literature on digital advocacy to analyze how intentionality of an organization is judged by its audiences (e.g., Ding & Wu, 2014; Godfrey, 2005; Godfrey et al., 2009). Though these studies have concentrated their efforts on examining how the reputational capital built up prior to a misconduct allows the attribution of good, rather than bad intentionality (Ding & Wu, 2014; Godfrey, 2005), their theorizing is useful to set the conceptual basis of our study.

We conduct a mixed methods study design (Caliandro & Grandini, 2016; Creswell, 2003, 2013; Greene & Caracelli, 2003; Plano Clark et al., 2013) of the #deleteuber boycott, using Twitter data. This boycott was launched in Twitter against Uber during the first weeks of 2017, when Uber drivers continued to provide airport-ride services despite the Travel Ban strikes at U.S. airports (Wong, 2017a). Even though Uber clarified that its actions were not intentional (Lynley, 2017), the boycott caused Uber to lose 200,000 customers, at least temporarily, when they uninstalled the app (Flynn, 2017).

Our exploratory study shows 12 distinct actus reus that appear in the rich collection of tweets in our data set. Further, boycotters' narratives indicate that the organization is not only a malevolent transgressor per se but also because a malevolent accomplice to a transgression, that is, there exists an organization specific mens rea and a shared one. Moreover, we see that digital advocates that are influencers—compared those that are part of the common population on Twitter—tend to punish Uber publicly because of its shared men rea with other Tech giants of the Silicon Valley.

We offer two specific contributions to the literature on public affairs that focus on online activism and boycotts (Albrecht et al., 2013; Balabanis, 2013; Braunsberger & Buckler, 2010; Illia, 2003; John & Klein, 2003; Kanol & Nat, 2017; Makarem & Haeran, 2016; Shah et al., 2019; Yuksel et al., 2019). Closely examining the 12 topics discussed on Twitter, we see that there are at least two legalistic narratives—that is, organizational-specific versus shared mens rea—behind a boycott which blur the difference between a direct and indirect boycott. Second, they suggest that there are two lurata—that is, juries—advocating for boycotts that are linked to the degree of influence of users. Taken together we can say that our contributions include both theoretical and methodological contributions to the literature on social advocacy and public affairs.

The paper is structured as follows: We first present scholarly work on online boycotts and discuss the attribution of mens rea during boycotts. We then present the #deleteuber boycott and illustrate the three explorative steps of analysis within our study. After expounding the main results, we present our emerging theoretical model and discuss the implications of the findings about shared mens rea for public affairs studies.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 #Boycotts, activism, and digital advocacy

Recent studies have shown growing evidence of consumers' ethical expectations from companies (Colleoni, 2013; Klein et al., 2004). Failing to fulfill these expectations invite the risk of becoming the target of consumer boycotts (Albrecht et al., 2013; Schmitz et al., 2020). Consumer boycotts, a call for the non-adoption of a product or service (Drillech & Basseporte, 1999; Friedman, 1999), can affect company outcomes by leading not only to a loss of reputation but also to financial loss. For instance, Hendel et al. (2017) have analyzed the market impact of a boycott organized in Israel on cottage cheese and shown that the boycott led to an immediate decline in prices, which remained low for the next 6 years! Bentzen and Smith (2002) have investigated how boycotts are used by activists to influence the actions of a government by analyzing French wine boycotts in Denmark protesting French nuclear testing in 1995–1996.

The disruptive impact of boycotts has been amplified by the diffusion of digital networks, where boycotters can easily organize against corporate misbehavior (Den Hond & De Bakker, 2007; Illia, 2003). Figenschou and Fredheim (2019) investigated how social media enable new forms of political advocacy and found that social media affordances make awareness-raising and community-building more efficient and purposeful for all groups at all levels. Kanol and Nat (2017) have analyzed how cause groups, which are more suitable for protest and calls to action, benefited greatly from the use of social media by pursuing two-way communication to mobilize publics. Brady et al. (2015) have demonstrated how social media have been successfully used in community organizing to promote worker rights and economic justice. In this paper we conceive digital advocacy as “an organized public effort, making collective claims of a target authority(s) in which civic initiators or supporters use digital media” (Edwards et al., 2013). Digital advocacy has recently begun to enjoy a growing significance considering how digitally native organizations are more naturally open to online feedback and supporter-led actions (Figenschou & Fredheim, 2019).

Kang (2012) has investigated the 2009 “Boycott Whole Foods”-campaign on Facebook in response to criticism by Whole Foods CEO John Mackey of the Obama administration's proposed health-care reforms. The boycott demonstrates volatile collective action through heterogeneous and heterarchical encounters. Similar results were found by Edrington and Lee (2018) in their work on #BlackLivesMatter that portrayed the intersections between public relations, social movements, and boycotts.

Despite growing evidence of how the novel nature of participation in digital advocacy has sparked a new wave of activism of institutional and non-institutional actors (Illia, 2003; Jacques, 2013), little attention is still given to consumer boycott motivations (Albrecht et al., 2013). Extant studies have mainly focused on boycotters' self-motivations, such as the desire to make a difference or the scope for self-enhancement (Albrecht et al., 2013; Braunsberger & Buckler, 2010; John & Klein, 2003; Klein et al., 2004) but have also explored boycotters' behavioral motivations, such as relational reciprocity (e.g., Hahn & Albert, 2017). Other factors have been recently investigated, such as political orientation (Fernandes, 2020), emotional context (Shah et al., 2019), and moral evaluations (Jacques, 2013). For instance, Fernandes (2020) has recently demonstrated how boycotters with different political orientations engage in boycotts for different reasons. Liberals engage in boycotts and buycotts1 that are associated with the protection of harm and fairness moral values (individualizing moral values), whereas conservatives engage in boycotts and buycotts that are associated with the protection of authority, loyalty, and purity or binding moral values. Shah et al. (2019) have shown the role of interpersonal emotions on a public's intentions to boycott an organization. While this body of knowledge suggests the relevance of studying the nature of the boycotter, few studies have analyzed the quasi-legal mental calculus that consumers perform to arrive at the decision to boycott. In the following sections, we explore the notion of mens rea and its linkage to a jury-like approach to boycotts.

2.2 Boycotts and organization-specific mens rea

The idea that boycotts are sanctions that follow a legalistic approach (Balabanis, 2013) is confirmed by other studies (Ding & Wu, 2014; Godfrey, 2005; Godfrey et al., 2009). Collectively they suggest that boycotters evaluate an argument for or against an organization in a similar way to a lurata, that is, a jury in a court-trial context. First, boycotters evaluate the actus reus, that is, the negative effects of the organizational act, most particularly its implications for people and society. Second, boycotters evaluate whether an organizational mens rea (Gardner, 1993; LaFave, 2000) is in place, that is, whether the organization holds a bad “state of mind and intention” (Godfrey et al., 2009, p. 428). Interacting these two forces and including the perspective of the boycotter herself, a conclusion is arrived at, to participate or not in the boycott.

Narratives put forward to claim the existence of an organizational mens rea are similar to those of lawyers who want to influence members of a trial-jury in court (Ding & Wu, 2014; Godfrey, 2005). The message is built on the argumentation that a wrongdoing is malevolent because it is part of a more general intrinsic bad scheme that makes the person guilty, and therefore sanctionable. Such attribution of culpability is argued in a similar way to the attribution of a cause to a behavior (Heider, 1958; Jones & Davis, 1965). When people claim for the causes of deeds, they rationally claim for evidence that allows them to impute the behavior to internal factors, rather than external forces. In particular, the correlation between the motive (e.g., having shown previous signs of discriminatory behaviors) and the behavior (behaving in a discriminatory way) allows to draw the conclusion that the bad action is not accidental but is prompted by internal controllable forces, rather than uncontrollable external ones (Jones & Davis, 1965). As suggested by crisis communication and management studies (Coombs, 1995), this type of attribution is at the core of an accusatory message during a business crisis, since public opinion claims that the company is responsible for the malevolent act when the organization shows three elements (Coombs, 1995, pp. 448–449): locus (whether a cause is internal or external), stability (whether an event is punctual or repetitive), and controllability (whether the cause is beyond the actor's control). For example, when Volkswagen was found to presumably cheat on carbon emissions of diesel, the general public considered it to be guilty because it was presumed that the software originally conceived to test the carbon emissions was malevolently installed in the car to manipulate outcomes of the test.

2.3 Boycotts and the shared mens rea of an organization

Recent scholarly work on boycotts (e.g., Balabanis, 2013) explains that one of the most widespread typologies of boycotts are the indirect ones, where the protestors target an organization while actually being annoyed with the policies of one of its partners or competitors, whether it be governmental or business (Friedman, 1999). In these boycotts, boycotters punish an organization because it is an additional accomplice—that is, a joint principal or an accomplice in a transgression—rather than the sole transgressor (Balabanis, 2013). The object of their narratives is therefore not so much the organization, but rather the inter-organizational context (Drillech & Basseporte, 1999; Friedman, 1999; Smith, 2000) and the fact that the organization somehow mirrors behaviors of this inter-organizational context.

Unlike the pure organizational-specific mens rea, a shared-mens rea (Balabanis, 2013) depends upon external causes, rather than internal ones. In particular, the shared-mens rea is built upon an attribution of both culpability and shame (Alicke, 1992, 2000; Crocker et al., 1993; DeJong, 1980; Weiner et al., 1988). The argumentation here is less rational and more affective as it raises the following reaction (e.g., Creed et al., 2014): “How could they do this? Do they have no shame?” The implicit assumption here is that the shameful act could have been easily avoided by the company but they chose not to do so and be complicit in the act. Therefore, shared-mens rea, similarly to organization-specific mens rea in that it rests on guilty intentionality; but in addition, it reflects a shameful complicit conformity (possibly opportunistically) to not do the right thing.

For example, when a company such as Apple hires a supplier such as Foxconn that was accused of not assuring minimal working conditions to employees it was shamed by the public jury.2 The shaming of Apple was not only for its opportunistic behavior but also a general condemnation of Apple for being among those companies3 that greedily rather than responsibly, preferred to prioritize money over people.4 When boycotters blame an organization for being malevolent when it commits a malpractice that is widespread in its inter-organizational context, they shame an organization based on certain common behaviors present at the cross-organizational level (e.g., Creed et al., 2014). Even if the evidence at hand would suggest that such an organization cannot easily bypass this practice, if it wants to be competitive in the marketplace; for instance in the case of animal testing of cosmetics, boycotters would still find that the company has voluntarily chosen to adhere to the practice and would therefore judge the shared mens rea according to their feeling that the company is part of a cohort of companies in the cosmetic industry that could have avoided animal testing but has not because it prioritized money over animal welfare.

3 METHODS

3.1 The #deleteuber boycott

In the first few months of 2017, Uber faced various controversies. At the end of January 2017, during the Travel Ban strikes at U.S. airports, Uber drivers continued to provide airport-ride service (Wong, 2017a). This was perceived as an opportunistic and insensitive move to exploit a taxi shortage caused by professional taxi drivers striking against an anti-immigration bill initiated by U.S. President Trump. The news media claim that this event motivated a massive number of users to uninstall the app, despite Uber's clarification that its actions were not premeditated (Lynley, 2017). The first tweet by @Bro_pair with the hashtag #deleteuber, urging users to delete the Uber app, was posted on January 29, 2017 and quickly went viral. A few weeks later, Uber was again in the public spotlight, when it was accused of exploitation by its drivers (Carson, 2017) and of promoting a sexist culture by one of its engineers (Carson, 2017; Hern, 2017; Horowitz, 2017). The media claimed that these two events exacerbated the online boycott and resulted in more than 200,000 users uninstalling the app by the end of March (Flynn, 2017). In the following weeks, the boycott became massive, inflamed by a variety of issues such as the distasteful behavior of its CEO, IP theft, attempts to defraud city regulators, and the use of the software called Greyball to avoid inspections in the states, where Uber was banned (Wong, 2017b). This unprecedented boycott was therefore a way for social media users to punish Uber for their overall bad intentionality.

The #deleteuber punitive action is a revelatory case because it provides us with the opportunity to study a boycott that was evaluated for both its intrinsic actions and for the actions of the environment it occupied. At the time of the boycott, Uber was publicly portrayed as a company whose founder's management style was reprehensible (Wong, 2017a, 2017b). Thus, digital advocates may attribute mens rea for intrinsic organizational motives. However, given that Uber is both one of the main representatives of the sharing economy and a very successful Silicon Valley technological giant, it is likely to suffer the consequences of any negative actions carried out by other technology giants or shared economy organizations simply because of association.

3.2 Database

Using Twitter's API, we collected tweets in English that included Uber anywhere in their body from January 7, 2017 to April 1, 2017 (the 13 weeks during which the #deleteuber boycott took place). After excluding illegible and non-English tweets, the sample contained 149,366 tweets.

3.3 Data analysis

Our mixed-methods research design (Creswell, 2003, 2013) combines quantitative and qualitative methods (Greene & Caracelli, 2003; Plano Clark et al., 2013) to study social media data (Caliandro & Grandini, 2016). In particular, we first applied content analysis using both qualitative techniques (i.e., pattern matching analysis), and quantitative techniques (i.e., network analysis and semi-automated content analysis) to explore and categorize the content of tweets, and then applied regression on the categorization to test for significant patterns in the data.

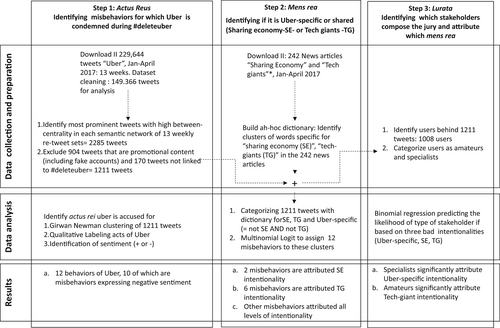

Three stages of analysis were followed (see Figure 1 for details about the three stages of analysis): In the first stage, Actus reus, we identify the acts that Uber was accused of by analyzing online discussions. In the second stage, Mens rea, we investigate how individuals assigned the intentionality behind Uber's alleged actions. In the third stage, Lurata, we identify the actors behind these online allegations.

3.3.1 Stage 1: Identifying actus reus attributed to Uber

To investigate the actions Uber was accused of, we first removed promotional content (including fake accounts) and then identified most shared and most central content (i.e., hashtags) in the conversation for each week, for a total of 1211 unique relevant tweets in the network of conversation. These represent a rich sample, especially when one considers the rapidity with which a tweet disappears from a typical user's landing page. Other studies conducted on Twitter have ended up with a proportionally smaller dataset than ours (e.g., Chew & Eysenbach, 2010 had 5395 tweets out of a total of over 2 million).

On this sample, we applied a semantic network analysis to allow the data to reveal the essence of the Twitter conversations. This requires three steps: First, we clustered the content to clearly distinct themes of discussion (Carley, 1997; Diesner & Carley, 2005; Guest et al., 2011). Second, two coders independently identified 12 main themes through manual content analysis. These represented conversations about the 12 acts of which Uber is accused. Intercoder reliability was 0.82. Third, we identified the characterizing sentiment in each of these acts using a machine-learning algorithm, achieving 80% accuracy. Table 1 provides a descriptive illustration of the output of this first step of analysis, where we indicate what these 12 conversations are about. Specifically, in the table, we provide details of the nature of topic, importance, and sentiment (Etter et al., 2018) toward each of the 12 conversations, the latter was measures on the basis of Loughran and McDonald (2011) dictionary which allows an automated classification of tweets based on sentiment expressed in it.

| Frequency | Sentiment | Issue/misbehavior | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 186 | Negative | Ethnic and Gender Discrimination | People dislike the fact that Uber has not stopped its services during the travel ban manifestation and transport strikes against the immigration ban. People also debate Uber as a tech company that discriminates against women in many instances, such as employees' sexual harassment and violence toward women clients. These conversations are not unique to Uber, because people debate these episodes since sexism episodes are typical of Silicon Valley tech startups. |

| 160 | Negative | Anarchism and Resistance (Anti-Capitalism) | The criticism, in some instances anti-capitalist, addressed to Uber and other tech giants is of ubiquitous character of these companies' services (i.e., one cannot function any more without these companies' services/products). |

| 154 | Negative | Corporate America | The link between politics and tech giants in the United States is controversial. People contest that corporations such as Uber could be in a position to develop social welfare, but only pursue their own business agenda. Uber and other tech giants are contested for their support of Trump. |

| 139 | Positive | Employability | Numerous and flexible employment opportunities provided by Uber are positively discussed. The focus here is on the flexibility and independence typical of sharing economy providers. |

| 115 | Negative | Toxic Culture | People contest the corporate culture of Uber that is considered too aggressive and in certain instances sexist. This is considered typical of CEOs of tech giants who are originally entrepreneurs (typically males), such as Uber's CEO Kalanick. |

| 111 | Positive | Mobility and Future | Futuristic projects and smart cities, that is, Uber and tech giants of Silicon Valley's commitment to innovation. Projects that are most discussed are self-driving and flying cars. |

| 99 | Negative | Human-based Service (Poor Quality) | The business model of sharing economy allows normal people to provide a service or good. Because this professionality decreases, the quality of experience for Uber mainly depends on drivers' human touch. |

| 87 | negative | Legal Infringements | Corporate behaviors that are at the limit of legality. Uber has been considered guilty of several crimes against states, companies, and even its own drivers. |

| 82 | negative | Dangerous Workers | Due to drivers' criminal records or risks of artificial intelligence (i.e., self-driving cars), Uber's drivers are perceived as potentially dangerous. People express the need to provide a clear regulatory framework of the shared economy. |

| 30 | Negative | Privacy | Privacy of data of users is a sensitive issue that is not only related to Uber but to all companies that, like Uber, extensively register clients' personal data. |

| 30 | Negative | Eroding Professional Categories | The negative impact on professional categories that companies like Uber create has been contested due to the flexible, non-regulated business. |

| 18 | Negative | Exploitation of Workers | This issue expresses the lack of protection of rights of providers of sharing economy services; specifically, for Uber, the drivers. |

3.3.2 Stage 2: Categorizing mens rea into Uber-specific versus shared

To investigate the user's attribution of organization-specific or shared mens rea to Uber, we inductively explored, without any coding scheme, which cohort of organizations is prominently named in tweets. This allowed us to identify that Uber is frequently associated not only with sharing economy companies, but also with tech giants of Silicon Valley. Hence, only then did we look at tweet content on the association of Uber with either technological giants or sharing economy firms in general. To do so, we created a list of keywords specific to Uber, tech giants, and sharing economy, respectively. This list was created statistically identifying the most relevant words used in newspaper articles (242 articles in English, from Lexis Nexis, January–April, 2017) to portray Uber, tech giants, and sharing economy, respectively, by applying the Naïve Bayes Classifier and chi-square values to the text (Kim et al., 2006).

To statistically classify a tweet as blaming Uber only or Uber as part of either technological giants or sharing economy firms in general, we applied a multinomial logistic regression (Greene, 2012) estimating the probability of a tweet belonging to the category of Uber, tech giant, or sharing economy, respectively. Our independent variables were the 12 (mis)behaviors expressed in each tweet. In the multinomial logit, we used sharing economy as the reference comparison criteria and therefore results are all to be compared against the sharing economy category.

3.3.3 Stage 3: Lurata

Finally, we classified user accounts into two groups according to their level of expertise of Twitter medium, using as a proxy the popularity of their accounts (i.e., number of followers):

Influential digital advocates

Those above the median number of followers (i.e., more than 3100 followers). This group mainly consists of micro and meso influential Twitter users who can be regarded as opinion leaders in the areas of business technology and innovation and who could therefore be considered as professionals. We labeled this group “Influential digital advocates,” as they either held the role of opinion leaders and highly regarded distributors of information about companies, or frequently published content about Uber and its industry.

Non-influential digital advocates

Those below the median number of followers (i.e., less than 3100 followers). We defined this group as “non-influential digital advocates,” as they did not show any influential role in the industry and published very few tweets on Uber.

We then investigate whether these two groups were attributing the means rea either to Uber, to tech giants, or sharing economy firms, we conducted a logistic regression (Peng et al., 2002) to highlight statistical differences across the two groups.

4 RESULTS

In the following section, we present results of the investigation of the Uber case on three different yet related elements of the boycott. In the first part, we show that there are 12″actus reus that are advocated in social media during the boycott. In the second part, we highlight that Uber is attributed a shared-means rea (both as a Sharing economy and Tech giants), but there is limited organization-specific mens rea attributed to Uber specifically. In the third part, we find that in particular shared mens rea about Tech giants is advocated by a specific lurata—the influential digital advocates. Overall, these findings portray a clear picture of how different groups penalize Uber's guilty intents and actions and how the judgment toward Uber is also affected by its belonging to both the sharing economy sector and the tech giants sector.

4.1 The actus reus: Misbehaviors Uber is accused of

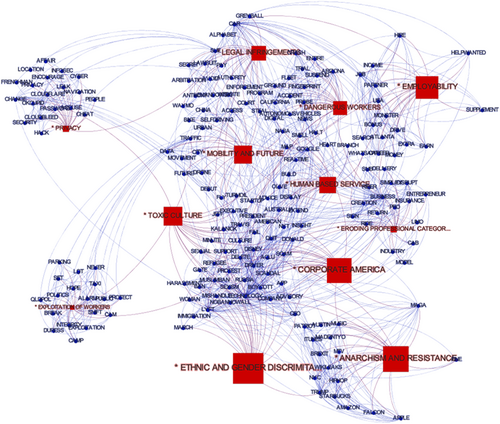

We observe 12 behaviors, of which 10 express negative sentiment and two express positive sentiment. In Figure 2,5 we include the most prominent words in these 12 networked conversations about Uber during the boycott.

tweet #2224: “Uber has a sexism problem, and so does Silicon Valley”

tweet #129: “What abt all the #Commercial #drivers that wil lose their jobs2 #Automation by #Uber,wil #SiliconValley b next in line after #Mexico #Trump?”

Collectively, these tweets appear to be expressions of frustration against Uber by individuals annoyed at some aspects of (mis)behavior that are specific to Uber and other aspects that tend to be exhibited by large American corporations in general. Uber's discriminatory culture of sexism, often referred to as the bro-culture, appears to be pervasive in many tech companies within Silicon Valley.

tweet: #288: “It's not FULL-TIME or PART-TIME – Uber is money anytime you want it. (atlanta) #Atlanta #Jobs”

tweet #3443: “Uber grounds entire self-driving fleet as it probes Arizona crash #news #technology #TechTongue #gadgets #Techno”

tweet #96: “When u get the #Uber driver who wants 2 talk… even with your headphones in and nose in your phone! #PleaseNo #MakeItStop #Antisocial #Nah”

tweet #734: “My uber driver is multitasking like crazy with his three phones! #uber #juno #gett #lyft”

tweet #1818: “NY police chief should support fingerprint background checks for Uber drivers #RideShare #NYC #Fingerprint #Certifix”

tweet #1848: “Taxi convoy now at Parliament as drivers protest, Uber regulation industry reform introduced in Vic. #sharingeconomy”

The negativity demonstrated by the incumbent in this sector counters to some extent the positive sentiment expressed by new entrants to the profession.

tweet: #2260: “WTF “…fake version of the app…ghost cars…” How @Uber Used #Greyball Tool to Deceive Authorities Worldwide”

Surprisingly, we see that two apparently important misbehaviors, data privacy and exploitation of workers, were the least frequently discussed and were also the most peripheral to the other misbehaviors debated during the boycott. As Figure 2 illustrates, these two misconducts are linked semantically to all other #deleteuber conversations by way of a third bad practice of Uber, namely, toxic culture.

tweet #2293: “catastrophic hacks like ongoing #Cloudbleed #breach affecting #Uber, #Yelp and #Fitbit underlines importance of securing data #infosec #cloud”

tweet #1072: “When Their Shifts End, Uber Drivers Set Up Camp in Parking Lots Across the U.S. #breaking #hope #politics #truth”

tweet #2164: “If Uber's Culture Is to Change, the CEO Must Go #recruitment #wearefunction”

4.2 The mens rea: More shared than Uber-specific

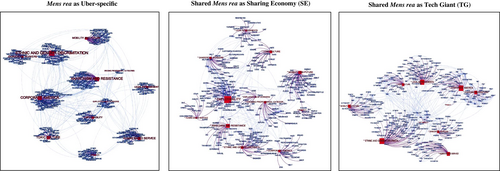

Figure 3 visualizes how each one of these (mis)behaviors identified in phase 1 is linked to a use of language that is typically seen not only when describing Uber but also the sharing economy or technological organizations. One can see that digital advocates are deliberating on the themes of the sharing economy and technological organizations, even when the ostensible topic of conversation is Uber.

Table 2 shows results of a model testing whether there are significant distinctions in the misbehaviors associated to Uber, Uber as part of the sharing economy and Uber as part of the tech giant industry (the model has a satisfactory model fit as follows: Pseudo R-square Nagelkerke = 0.211 and model fit significance = 0.000).

| Mens reaa | B | Std. error | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% confidence interval for Exp (B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| Uber specific mens rea | Intercept | 0.60 | 0.21 | 0.00 | |||

| Anarchism and Resistance | −0.11 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.51 | 1.53 | |

| Corporate America | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 1.55 | 0.85 | 2.81 | |

| Dangerous Workers | −0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.725 | 0.38 | 1.38 | |

| Employability | −1.41 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.242 | 0.13 | 0.42 | |

| Eroding Prof. Categories | −3.24 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.039 | 0.00 | 0.17 | |

| Ethnic and Gender Discrimination | 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 1.85 | 1.04 | 3.28 | |

| Exploitation of Workers | −0.37 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.685 | 0.24 | 1.90 | |

| Human Based Service | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.04 | 2.04 | 1.01 | 4.15 | |

| Legal Infringements | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.80 | 1.09 | 0.52 | 2.27 | |

| Mobility and Future | −0.44 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 1.15 | |

| Privacy | −0.10 | 0.43 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.38 | 2.11 | |

| Toxic Culture | 0b | ||||||

| Tech Giants (TG) shared mens rea | Intercept | −0.58 | 0.28 | 0.04 | |||

| Anarchism and Resistance | −0.13 | 0.37 | 0.72 | 0.87 | 0.42 | 1.83 | |

| Corporate America | 0.97 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 2.65 | 1.27 | 5.52 | |

| Dangerous Workers | 0.08 | 0.42 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 0.47 | 2.47 | |

| Employability | −3.27 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.17 | |

| Eroding Prof. Categories | −21.87 | 0.00 | 3.1E-10 | 3.1E-10 | 3.1E-10 | ||

| Ethnic and Gender Discrimination | 0.94 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 2.57 | 1.25 | 5.28 | |

| Exploitation of Workers | −20.35 | 0.00 | 1.4E-09 | 1.4E-09 | 1.4E-09 | ||

| Human Based Service | 1.20 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 3.30 | 1.44 | 7.75 | |

| Legal Infringements | 1.47 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 4.36 | 1.94 | 9.79 | |

| Mobility and Future | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.47 | 2.14 | |

| Privacy | −1.81 | 1.08 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 1.35 | |

| Toxic Culture | 0b | ||||||

- a The reference category is shared mens rea with sharing economy (SE).

- b This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

Interestingly, the results show that no misbehavior is exclusively attributed to Uber. Themes are either associated to both Uber and Tech giants (but not to Uber and sharing economy), such as ethnic and gender discrimination (β = 0.616, p = 0.0036 vs. β = 0.976.240, p = 0.000, respectively), and human-based service (β = 0.717; p = 0.047 vs. β = 1.206; p = 0.005, respectively), or to the combination of Uber, tech giants, and sharing economy. The fact that Uber is part of the tech giants sector seem to rub off in the prejudicial public opinion much more strongly than its membership in the sharing economy.

4.2.1 Mens rea shared with sharing economy organizations

We identify two misbehaviors that are associated exclusively with sharing economy organizations (but not with Uber or tech giants) and two that are clearly not associated with sharing economy firms. Employability and eroding professional categories appear to be misbehaviors that pertain typically to sharing economy and are not specific to Uber alone or to other tech giants, as their coefficients are negative and significant for both Uber-specific references (Employability: β = −3.240; p = 0.000; Eroding professional categories: β = −3.240; p = 0.000), and tech giants (Employability: β = −3.279; p = 0.000; Eroding professional categories: β = −3.279; p = 0.000). However, ethnic and gender discrimination and human-based service appear to not be significantly associated with behaviors typical of the sharing economy, but rather to behaviors specific to both tech giants (β = 0.976.240; p = 0.000; β = 0.717; p = 0.047, respectively), and Uber (β = 0.616; p = 0.036; β = 1.206; p = 0.005, respectively).

4.2.2 Mens rea shared with technological giants

Digital advocates appear to be associating Corporate America-related actions (market-oriented capitalistic practices and legal infringement) to misbehaviors that are repetitive at the cross-organizational level among tech giants in general (β = 0.976.240; p = 0.000, β = 0.1.473; p = 0.000). It is interesting that, while Uber is often characterized as capitalistic and a lawbreaker, these two traits are commonly ascribed to tech giants in general.

4.3 Lurata: Influential digital advocates attribute shared mens rea

Even though all digital advocates castigate Uber for the same misbehaviors, not all of them attribute mens rea in the same way. The binomial logistic regression (see Table 3) that compares differences among “non-influential” and “influential” digital advocates suggests that there is a significant difference in how these two types of digital advocates attribute the difference mens rea and sustain the punitive action toward Uber (p = 0.027; Nagelkerke R Square = 0.019; Hosmer and Lemeshow Test = 1.000; overall percentage of cases explained is 93.8%).

| B | S.E. | Wald | f | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Step 1a | a. | 6.175 | 2 | 0.046 | |||||

| 1. Uber-specific mens rea | 1.050 | 0.447 | 5.524 | 1 | 0.019 | 2.857 | 1.191 | 6.857 | |

| 2. Shared mens rea Sharing Economy | 0.666 | 0.484 | 1.899 | 1 | 0.168 | 1.947 | 0.755 | 5.025 | |

| Constant | −3.507 | 0.414 | 71.627 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.030 | |||

- Note: Predicted Probability is for influential digital advocates.

- a Variable(s) entered on step 1 for shared mens rea Tech Giant (TG).

Table 3 shows that, in comparison to non-influential digital advocates, influential digital advocates are significantly more likely to discuss tech-giant-centric and Uber-specific themes but not shared economy-related themes. However, as our second step of analysis indicates, Uber-specific themes are never the most significant debated themes in our dataset, hence, we draw the conclusion that influential digital advocates are significantly more likely to discuss tech-giant centric themes. These two actors do not show statistically significant differences (p = 0.168) in discussing Uber's misbehaviors as being typical of sharing economy firms. They do reveal a statistical difference in discussing.

5 DISCUSSION

This paper aims at exploring the mechanism of a social advocacy situation specifically to do with an online boycott called for on social media. The lurata or public acting as jury observe the actus reus, the guilty acts, gauge the mens rea, the guilty intent and decide to participate or not in the online boycott. Examining over 1200 tweets related to the #deleteuber campaign we identify 12 themes in the public discourse. We then see that the mens rea attribution is nuanced in that there exists a uber-specific mens rea and shared mens rea that arises from uber being part of the tech giants of silicon valley. As seen in the literature, the organization specific mens rea tends to be a rational deduction based on the acts committed by the firm, whereas the shared mens rea is often an affective response to an organization that chose to be complicit in the shameful acts of its peers. We see clear evidence that the #deleteuber boycott displayed both shades of mens rea.

This discussion of the two flavors of mens rea simultaneously manifesting in the boycott is further nuanced in that two classes of lurata focus on different actus reus and hence different mens rea. The influential twitter personalities who perhaps have greater insights to the internal operations of Uber or care more about the specifics of Uber tend to focus on the organization specific mens rea. The majority of the twitter users, those who typically do not wield much influence are perhaps less discerning of what is uniquely uber-specific and tend to paint the sector with a broad brush and react less rationally and more affectively in attributing the shared mens rea.

These findings improve the current understanding of the quasi-legal motivations advocated during boycotts and, in particular, of the attribution of mens rea because they indicate that narratives advocating for bad intentionality during a direct boycott, such as the one of Uber, may be about a shame shared with others, rather than uniquely an individual culpability. Typically, in offline boycotts, the motivation of shame was associated with indirect boycotts (see of Balabanis (2013) and Friedman (1999) for a complete review). With online advocacy it is likely that the boundaries between direct and indirect boycotts has become rather blurred. Boycotters may just as easily mount a direct boycott for a shared mens rea as they could for an organization specific mens rea. We see a possibly social control mechanism where the public punishes a firms act of commission with guilty intent as well as the firms act of omission in doing the right thing when its peers were committing shameful acts.

5.1 # shared-mens rea : Legalistic narrative blurring the difference between direct and indirect boycotts

Previous studies on boycotts (Balabanis, 2013; Barclay et al., 2011) build on studies analyzing organizational mens rea (Ding & Wu, 2014; Godfrey, 2005; Godfrey et al., 2009) suggesting that boycotters evaluate the organization in a similar way to a lurata, that is, a jury in a court-trial context. That is, when they judge an actus reus, they think rationally and objectively about an event such as a misdeed, since they consider the internal cause of an action to be controllable, whereas external causes are more likely to be uncontrollable. Our study, however, suggests that boycotters attribute the shared mens rea to an organization in a less rational way than postulated by previous studies (Balabanis, 2013; Barclay et al., 2011) because they prejudicially shame an organization, when it is considered to be part of a cohort of organizations—in the case of Uber, shared economy or Tech giants—that are blamable for certain misconduct—in our specific case, gender or ethnic discrimination. When they do so, they differentiate between the cause and controllability of a disapproved action. Though subtle, this difference allows us to understand why digital advocates in our study attribute the most debated transgression, ethnic and gender discrimination, to Uber's shared mens rea with Silicon Valley's other technological giants. Even if digital advocates realize that Uber was not alone in propagating racial discrimination or failing to enforce gender disparity in the sector, they consider Uber to be responsible, since they had a degree of control that they have chosen not to exercise.

Our contribution to the literature is not only to highlight that #boycotts represent a new form of digital advocacy that blurs the difference between direct and indirect boycotts. Also we highlight that, while digital advocates evaluate an organizational mens rea, they do not follow only the general rules of attribution (Heider, 1958), as outlined by previous studies (Ding & Wu, 2014; Godfrey, 2005; Godfrey et al., 2009), but also follow specific rules concerning the attribution of shame (Alicke, 1992, 2000; Crocker et al., 1993; DeJong, 1980 ) that is a much more affective social evaluation of organizations (Etter et al., 2018; Etter et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). From our viewpoint, this opens up also new avenues for investigation in the field of the attribution of organizational shame (e.g., Creed et al., 2014; Roulet, 2020)—and more generally of attribution of affective social evaluations online (Etter et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020)—because it suggests that when #boycotters express a strongly negative social evaluation of an organization, they are to a certain extent expressing an affective evaluation of an organization-specific and shared mens rea. This is a contribution to studies on organizational shame because it allows to understand that shame is affectively ascribed to organizations by means of mens rea : an organization is shamed because it is guilty (organizational mens rea) or because it is accomplice in a misconduct (shared mens rea).

5.2 Two juries advocating for #boycotts, one promotes instinctively the narrative of shame

Today, at least in the Twittersphere, boycotters appear to be composed by two distinct but yet complementary public juries. On the one hand, there is a first public jury composed of influencers. This jury is made up of users whose profile has a high status on Twitter (Ciszek & Logan, 2018; Edrington & Lee, 2018; Figenschou & Fredheim, 2019; Kanol & Nat, 2017)—that is, high number of followers—that shows their institutional gatekeeping power in Twitter. This jury is focused around a narrative that advocates for shared mens rea as tech giant. On the other hand, there is a second jury composed by users having low status in Twitter. This jury spreads a legalistic narrative that is mixed, since it is not conveying a shared mens rea over a specific one. These findings provide a contribution to studies on public affairs, digital activism, and boycotts (Brady et al., 2015; Ciszek & Logan, 2018; Edrington & Lee, 2018; Figenschou & Fredheim, 2019; Hon, 2015; Ibrahim, 2019; Kang, 2012; Kanol & Nat, 2017; Lovejoy et al., 2012) because we suggest that actors institutionalized in Twitter as “influential” tend to advocate with argumentations that are shared-specific, but not related to the primary context (that for Uber is sharing economy); rather a broader and general context (taht for Uber is tech giant).

This suggests surprisingly that the first jury carries out an instinctive evaluation compared to the second jury, which instead punishes the organization without primarily shaming it for its misconduct. The narrative the first jury proposes is about shaming, as they consider it a shame that the organization is behaving as others in a specific industry. Their message prejudicially condemns the organization for being a part of a cohort of companies. These findings contribute to those studies that have recently urged for the necessity to further explore the role of influential actors and non-institutional influential advocates in social media within boycotts (Brady et al., 2015; Ciszek & Logan, 2018; Edrington & Lee, 2018; Hon, 2015).

5.3 Practical contributions

From a practical perspective, the managers working for a boycotted organization can learn the importance of developing different strategies to counter the blame being expressed by different digital advocates in situations where they need to provide justification of their non-intentionality. Not only do they have to show that they are not the cause of the misbehavior, but they also have to reiterate their lack of control, even where this may appear to be self-evident, such as where the cause clearly emanates from extrinsic forces. Specific to Uber and the boycott, our study suggests that the organization would not be able to justify its non-intentionality and stop the boycott simply by arguing that it did not instigate drivers to offer their services during the Travel Ban; nor would dis-associating itself from the group of Silicon Valley tech giants be sufficient to stop the boycott. As a matter of fact, anecdotal evidences indicate that Uber did indeed explain that it did not order drivers to provide the service (Wong, 2017c), and the company implemented a number of measures intended to dis-associate itself from the tech giant group of organizations, including the CEO withdrawing from Trump's advisory board (Wong, 2017c). These two justifications were insufficient to enable Uber to stop the chain of events related to the boycott, and so, we infer that the company did not provide digital advocates with sufficiently satisfactory evidence. What might have helped, however, would have been for the company to provide an explanation of the governance rules of Uber's platform with regards to its drivers' freedom. Furthermore, an explanation of the company's presence on the advisory board does not imply that Uber has any control over Trump's politics or indeed the general behavioral scheme of Silicon Valley.

5.4 Methodological contribution

We adopt a novel mixed method approach to tackle a typically under observed public jury mechanism. In the case of offline boycotts, it is not easily evident how the public arrive at the conclusion to initiate a boycott. In the case of an online boycott, we are presented with a unique opportunity to examine this mechanism. The modeling approach to identifying the actus reus allows us to take an unbiased approach to identifying the underlying themes. The data here is allowed to speak with no observer bias. In keeping with this philosophy, we do not impose characteristics of Tech giants or Sharing economy firms. This surfaces from the media mentions referencing these two sectors. Lastly, we do not impose a definition of who is an influential tweeter versus who is not. We believe this three-stage approach lends itself to examining future phenomena.

5.5 Limitations

We focused this study on Uber, and specifically on the exploration of Uber as a sharing economy and technological organization. While we believe that this is a perfect example for studying the mens rea process during a boycott, one might question the generalizability of the findings. It would be particularly interesting to explore whether misconducts identified in this study are common to the boycotts of other sharing economy organizations or to other more general types of organization. In addition, we identified two typologies of digital advocates—influential and non-influential—by segmenting digital advocates based on the number of their followers. It is possible that other segmentations based on, say, a ratio of the number of followers and followees, or the number of retweets, and so forth may have led to other categories of digital advocates. Given the study's limitation in space and scope, we have adopted this logical and rather simplistic categorization model. Finally, our study has analyzed a boycott that has taken the advent of Twitter, which is one online social media platform with its specific affordances. For example, Twitter allows individuals to participate in conversations even if they are not linked structurally with a follower-followee relationship. Though we do not believe that the emergence uber-specific and tech-giant (or shared economy) narratives may be influenced by this affordance, in order to corroborate our findings on the two types of mens rea—shared and organization specific—and the two type of lurata—one composed by influential institutionalized actors and non institutionalized actors—further research needs to conduct other analysis on boycotts organized in other social media such as Instagram or Facebook for example.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our research would not have been possible without the financial support provided by BBVA Foundation Individual Grants (Spain). Moreover, we have greatly benefited from the conversations and suggestions of a number of peers or senior scholars. Comments by Robert Phillips (York University), Alessandra Zamparini (Università della Svizzera Italiana) , Christian Fiesler (BI) have have been crucial to shape our study and its design. We are also grateful to the participants at the Sharing Economy workshop in China on “Challenges and opportunities in the sharing economy” and to participants of EGOS pre-conference workshop on “Opportunities and controversies of sharing economy” whose comments about our initial ideas were very constructive and helpful in shaping this paper. Finally, a special thanks goes to Anika Clausen who helped to take care of formatting and last revision of the paper. Open Access Funding provided by Universite de Fribourg.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors whose names are listed in this title page certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Biographies

Laura Illia is Professor (Chair of Communication, Business and Social Responsibility) at the Faculty of Management, Economics and Social Science at the University of Fribourg (CH). Her current research focuses on how discourses, narratives and conversations become crucial to comprehend organizational challenges in the contemporary networked and digitalized media landscape where Artificial Intelligence (AI) agents are taking the advent. By applying new digital methods such as machine learning to big dataset she looks into questions of legitimacy, stigma, and social responsibility. She has been doing research at IE University (ES), University of Cambridge (UK), London School of Economics and Political Science (UK) and Università della Svizzera Italiana (CH). Her works are published in journals like MIT Sloan Management Review, Journal of Business Ethics, British Journal of Management, Journal of Management Inquiry, Business and Society, Journal of Business Research and others. She currently serves on the Editorial Board of the Journal of Management Studies (Wiley), Journal of Business Ethics (Springer), Business & Society (Sage) among others.

Elanor Colleoni is currently Assistant Professor at IULM University Milan in the field of corporate reputation, organizational legitimacy and corporate social responsibility, with a particolar focus on the impact of new communication technologies on corporate reputation. She has been appointed Research director of the Center for Strategic Communication at IULM (CECOMS-Iulm). Prior to that, she worked as Global Senior Director of RepTrak Methodology at Reputation Institute, a company leader in corporate reputation consultancy. She has worked as Assistant Professor at Copenhagen Business School, Visiting Scholar at University of Chicago at Illinois UIC-Chicago, visiting scholar at WZB in Berlin and CEPS in Luxemburg. Her research has been published in leading management and communication journals, such as Academy of Management Review, Business & Society, Journal of Communication, among others. She is also recognized as CSR and Reputation expert by the European Commission, where she has served for several years as an independent evaluator for the FP7 and Horizon 2020 Call CAPS (Collective Awareness Platforms for Sustainability and Social Innovation).

Kiron Ravindran's research and teaching interests in Information Systems comes from his engineering and management education, industry experience, training in quantitative methods and a keen interest in emerging technologies. Dr. Ravindran's experience includes working in the manufacturing and information technology sectors. His research interests are in the areas of Sourcing Strategy, Information Technology Management, Governance and Contract Design, Organizational Social Network Analysis, and Economics of Information Systems.

Nuccio Ludovico, Ph.D. in Social Psychology, Developmental Psychology and Educational Research, is also a Ph.D. candidate at the Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Groningen. His research activity concerns social actors' perception towards socially relevant and sustainability related issues, emerging from the digital communication environment. Currently, his research focuses on organizational knowledge formation and diffusion processes, enabled by actors' relational network, that take place in the web sphere. He collaborated in both national and international funded projects (EC H2020), in which he managed the methodological aspects of the research. In 2016 and 2017 respectively, he achieved a research scholarship at Claremont Graduate University (CA) and a research fellowship at IE Business School of Madrid. Additionally, he works as innovation strategy consultant for Italian companies and is member of the Scientific Board at Nahima Foundation as contact point and reference for Social Sciences in the foundation's projects.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1 A buycott, is a conscious choice by a consumer to avoid products of a company that she deems unethical and instead opts for products from a competing firm that is ethical.

- 2 Who's Really to Blame for Apple's Chinese Labor Problems? By Hanqing Chen https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/whos-really-to-blame-for-apples-chinese-labor-problems/253892/ (accessed on July 23rd 2021).

- 3 In China, Apple faces its “Nike moment”? https://www.reuters.com/article/us-apple-china-idUSTRE8250FQ20120306.

- 4 Former employees say Apple stood by while suppliers violated Chinese labor laws https://www.theverge.com/2020/12/9/22166286/apple-china-labor-violations-temporary-workers.

- 5 To visualize Figure 2, we calculated the probability that each word coded with Wordstat belongs to a tweet associated with each one of the 12 identified conversations (Chen & Chen, 2011; Meesad et al., 2011).