Impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness: Evidence from emerging market economies

Funding information: This study did not receive financial support from any funding agency the public, commercial, or not for profit organisations/sectors.

Abstract

The objective of the present study is to examine the impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness in 21 Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) with the help of three sub-samples comprising America, Asia, and EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa) countries from 2006 to 2019. For this objective, panel corrected standard error model is used to resolve the problem of cross-sectional dependence, group-wise heteroscedasticity, and panel autocorrelation. The results of the study reveal that economic growth plays a positive role in determining the happiness of EMEs of America and EMEA sample countries. At the same time, globalisation and inflation affect the happiness of people in American sample countries in a negative way. In the sample of Asian countries, social support has a substantial impact on happiness. Corruption in the government and business sectors reduces the happiness of selected countries of both Asia and America. This article contributes to the existing literature by first time considering EMEs which have undergone liberalisation reforms and experienced transformation in their socioeconomic conditions. In conclusion, the study suggests that GDP per capita and social support positively stimulates happiness while the perception of corruption negatively impacts happiness in selected EMEs. These implications can help in building a line of actions for strengthening anti-corruption institutions and promoting social integrations among these EMEs.

1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

The United Nations (UN) has recognised World Happiness Day on 20th March every year since 2013. Happiness1 is a multidisciplinary concept that involves the social, economic, political, cultural, spiritual, and psychological aspects of a person. Discussions related to happiness are not new in the history of economic thought. Smith (1776) recognised that relative wealth is a significant determinant of happiness. However, Bentham (1989) advocated that society's goals must be based on the greatest happiness principle.2 Later, Jevons (1871) used the law of diminishing marginal utility of money to explain that more commodities or wealth cannot consistently increase one's satisfaction or utility. Later, the views of welfare economists have shifted the world's perspective of wellbeing from profit maximisation to welfare maximisation (Pigou, 1912; Scitovsky, 1976; Sen, 1985). But they only analysed the choices and preferences available to the people, which are considered as only the means of happiness (Ng, 1997). In 1972, Bhutan drew the attention of the world due to its new perspective of the Gross National Happiness (GNH) index. This index aims to maintain the balance between material, that is, money and property, and non-material, that is, culture, environment, spirituality, society, and community wellbeing of life (Benth Gupta & Agrawal, 2017). Afterwards, United Nations General Assembly accepted happiness as an independent goal for all countries of the world in 2011.

Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) contain 85% of the world population and contribute to 59% of total world output. Foremost EMEs like Brazil, South Korea, Russia, China, India, and Indonesia are projected to contribute 45% of world GDP by 2025 (World Bank, 2011). The term EMEs describes the social or business activity of a nation in the process of rapid growth and industrialisation. These countries have gone through liberalisation reforms and experienced a fundamental transition in their institutions. Higher public investments and growth have improved the level of human capital and education quality in these countries (Euromonitor, 2016). The process of industrialisation, trade, and adoption of technology have both direct and an indirect effects on socioeconomic conditions in these countries. These conditions will ultimately influence the happiness of the people of EMEs. Hence, it is crucial to examine the impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness in EMEs.

Few scholars have investigated the impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness on the sample of EMEs (Fereidouni et al., 2013; Graham & Pettinato, 2002). Graham and Pettinato (2002) found that relative income is more important than absolute income in determining subjective wellbeing in Russia and Peru. While, Fereidouni et al. (2013) found that higher political stability, low violence, controlled corruption, and effective government have a positive impact on happiness in the Middle East and North African region during 2009–2011. But these studies are limited to few countries of EMEs. Most of the above studies are based on cross-sectional setup and traditional method of panel data (Arnout, 2020; Beja, 2017; Dorn et al., 2007; Li & An, 2020; Perovic & Golem, 2010; Welsch, 2008; Woo, 2018). Our result is based on panel data which can give a better causal relationship and changes in happiness over a period of time.

So far, it is evident from the literature that most of the studies are concentrated on the impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness in the developed economies. Moreover, mainly, cross-sectional studies have been carried out in the previous studies. We have little evidence regarding the impact of socioeconomic variables on happiness in EMEs. Therefore, the present article is focused on examining the impact of socioeconomic parameters on happiness with a sample of 21 EMEs over the period 2006–2019. A panel corrected standard error (PCSE) model is adopted in the study to achieve the objective of this article. The contribution of this article is in the following manner: (1) the study focuses on a panel of 21 EMEs and its three sub-categories: American EMEs, Asian EMEs, and Europe, Middle East & Africa countries of EMEs. (2) The robust analytical technique, that is, Prais–Winsten regression by using PCSEs, is applied due to the nature of data. This model accounts for cross-sectional dependence (CSD), autocorrelation, and panel groupwise heteroskedasticity. (3) This study will contribute to literature related to socioeconomic variables on happiness in EMEs which is largely ignored in the literature. The empirical findings can help the policy makers of EMEs in formulating different policies for promoting a higher level of happiness and wellbeing for their citizens.

The remaining part of the article is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the Theories of Happiness. Section 3 is related with literature related to happiness and socioeconomic indicators. Section 4 explains the data and model specification. Section 5 shows the results and discussion. Finally, Section 6 deals with the conclusion and policy implications.

2 THEORIES OF HAPPINESS

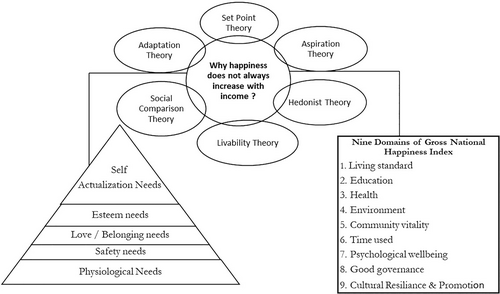

There are a few theories that explain why an increase in income is necessary but not a sufficient condition for one's happiness. Maslow's (1954) Need Hierarchy Theory advocates that only after fulfilling basic needs, an individual meets its security and belonging needs and lastly move towards self-actualisation needs. While, Aspiration Theory of Easterlin (1974) suggests that the happiness of people depends on the gap between the expected income and actual income. In contrast, Adaptation Theory believes that individuals have a stable equilibrium state of happiness. When this equilibrium state is disturbed by a positive or a negative shock, there are only temporary effects because individuals adapt to the new situations (Brickman et al., 1978). According to Set Point Theory, the level of happiness fluctuates around the set point, which is biologically determined and remains constant (Lucas, 2007; Veenhoven & Ehrhardt, 1995). According to livability theory, happiness is an outcome of certain objective factors that are socially important and related to income, health, education, and so forth. Hedonistic Theory by Seligman and Royzman (2003) stated that happiness is closely related to subjective feelings and emotions. According to Social Comparison Theory, happiness is not driven by objective factors or absolute factors, but it depends on relative judgements (Michalos, 1985). Individual happiness is related to two types of comparisons—the comparison between the other individuals and the comparison with one's own past. A person becomes happier when s/he found that only s/he is going to be richer and successful than others (Clark, 2011). Binswanger (2006) argued that happiness is like a treadmill where people work more and more for money to get happiness. But actual happiness level remains constant. This treadmill effect intensifies more when there is a comparison among different income groups. The above discussion is summarised in Figure 1, given below.

3 REVIEW OF LITERATURE

3.1 Economic growth and happiness linkage

Easterlin (1974) was the first economist who argued that the happiness of people is weakly related to income in his study of USA during 1946–1970. Happiness increases with the increase in income. But this income-happiness nexus becomes weak after a specific point of time. This phenomenon is popularly known as Easterlin Paradox. Later, Easterlin and Angelescu (2009) validated this nexus in Japan and concluded that the GDP per capita of Japan has increased equivalent to one-third of the USA, but their subjective well-being (SWB) had remained unchanged. Ng (2002) studied the East Asian happiness gap and found that these countries performed poorly in the happiness survey despite achieving high income.

Kenny (1999) supported Easterlin (1974) and came up with a similar result that economic growth increases happiness, but this direct relationship broke down after reaching the threshold level. However, Howell and Howell (2008) found that economic status influenced SWB strongly in developing countries as compared to developed countries. Tiwari and Mutascu (2015) reported that economic growth had a negative effect on happiness in the short run in 23 developed economies. In contrast to this, Kumari, Kumar, and Sahu (2021) found that economic growth promotes subjective wellbeing in G20 countries by the channel of more sustainable energy consumption. Recently, Cuong (2020) found that higher income in the form of social pension has increased the happiness of older people in Vietnam.

3.2 Globalisation and happiness

It has always been in question whether globalisation has improved the wellbeing of the people or not. Sen (2002) highlighted that globalisation has strengthened the connectivity of the world and created awareness regarding democracy, elementary education, health, social safety net, greater specialisation, and better opportunities for the people. But at the same time, globalisation has resulted in high inequality, hunger, mortality, illiteracy, economic insecurity, social exclusion, and lack of political freedom in the newly liberalised markets (Sen, 2005; Stiglitz, 2003).

Tsai et al. (2012) evaluated the link between micro globalisation and SWB of east and southeast countries. There is a positive impact of the foreign language and foreign exposure on job satisfaction and life accomplishment. While contrast to this, Xin and Smyth (2010) inspected the nexus between SWB and economic openness in 30 cities of China. It was observed that Central and Coastal Chinese cities, which were most exposed to the global markets, had the lowest level of SWB and vice versa. In another study in China, Ma and Chen (2020) got an inverse U-shaped relation between trade openness and happiness. Welsch and Kühling (2016) revealed that increased trade openness had enhanced SWB in 30 OECD countries during 1990–2009. Recently, Kumari, Sahu, and Kumar (2021) found that economic globalisation has a positive impact on happiness in the long run but in the short it affects happiness negatively in lower-middle income countries of Asia. However, Helliwell and Huang (2008) and Ram (2009) got an insignificant relationship between trade openness and life satisfaction.

3.3 Social support and happiness

Social capital plays a crucial role in determining the happiness of an individual. The level of trust, cooperation, affection, tolerance, and so forth, influences a person's happiness. Bjørnskov (2003) investigated the reason behind the happiness of the happiest countries of the world. He accepted that social capital is an essential tool for increasing happiness in Switzerland and Scandinavian countries. Bartolini et al. (2013) argued that the lack of social networks and trust in institutions are the main factor behind the declining happiness of US citizens. In contrast, Ram (2010) found that social capital does not bring happiness in transition countries. Chang (2009) concluded that social capital positively affects happiness in Taiwan. D'Agostino et al. (2019) found a positive relation between institutional trust and life satisfaction in European youths aged 18–34 years. Sarracino (2010) presented a declining trend in social capital and subjective wellbeing in 11 countries of Europe. Bartolini and Sarracino (2014) concluded that social capital has a strong positive impact on SWB in the long run as compared to short run. Similarly, Calcagnini and Perugini (2019) used blood donations, length of bike lanes, social networking area for active commuting as a substitute of social capital and found their positive impact on wellbeing in Italy. Neira et al. (2019) used rules of civic engagement, trust, social connections as a proxy of social capital. It was found that these indicators have stronger positive impact on least happy people than happiest people.

3.4 Inflation and happiness

Inflation is also one of the crucial variables which influence the happiness of people. Perovic and Golem (2010) found a positive linkage between inflation and happiness in 13 transition countries because mild inflation with nominal rigidities gives investment incentives. Further, it results into a higher economic growth through increased productivity and employability. While Frey and Stutzer (2000) said that inflation reduces happiness because of fear of lower purchasing power, uncertainty, worsening of the income distribution, economic and political instability, and reduction of country's respect due to declining exchange rate. Di Tella et al. (2001) reported a negative association between inflation and happiness in 12 European countries. It was found that an increase in inflation by one point reduces happiness by 0.01 points. An additional $850 per year must be given to compensate for the rise in inflation and to maintain the same satisfaction level. In a similar line, Graham and Pettinato (2001) noticed that inflation had adverse effect on happiness in Latin America. In addition to this study, Blanchflower (2007) advocated that the past experience of inflation during an individual's adult time had a more adverse impact on happiness than present day's inflation. Similarly, Glatz and Eder (2019) and Kumari, Sahu, and Kumar (2021) revealed that declining inflation positively influence SWB.

3.5 Corruption and happiness

Corruption is seen as the “misuse of public office for private gain” (Sandholtz & Koetzele, 2000). Wu and Zhu (2016) advocated that corruption reduces Chinese people's happiness more because people feel shame and guilt. The psychological cost of corruption is higher than the monetary cost (Welsch, 2008). In another cross-sectional study, Arvin and Lew (2014) argued that corruption badly affects people's well-being in high-income countries compared to low-income countries. It happened because citizens of high-income countries are more conscious of their rights and anti-corruption policies. Thus any violation of rules severely affects them (Sapsford et al., 2019). In another study, Tavits (2008) investigated the impact of corruption and representation on people's subjective wellbeing in European countries and found that subjective wellbeing was high when the government was less corrupt. Ryan and Deci (2001) accepted that equality and transparency are crucial for increasing people's wellbeing. In a cross-country analysis of 126 countries, Li and An (2020) found that there is a fall in subjective wellbeing by 0.23 point with a rise in 10 points corruption level in government.

4 DATASET AND MODEL SPECIFICATION

This study examines the panel dataset of 21 EMEs3 worldwide during the period from 2006 to 2019. EMEs are based on an emerging market index developed by Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) in 1988. This index is based on economic development, liquidity, and market accessibility. Currently, there are 26 countries that come under the category of EMEs. However, 21 countries have been selected in this study based on the data availability. These countries are further divided into three-continent panels: America, Asia, and Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA). Please refer to Tables 3 and 4.

The study has adopted the Cantril life ladder data as an indicator of happiness. The life ladder is measured from 0 to 10, where 0 refers to the bottom satisfaction level, while the value 10 refers to the highest happiness level. The life ladder has been used as a proxy for happiness in many studies in the literature (Lin et al., 2017; Zweig, 2015). Per capita GDP, trade openness, inflation, perception of corruption, and social support are taken as the proxy for socioeconomic variables. A complete description of the variables is presented in Table 1.

| Variables | Symbol | Description | Units | Source | Expected sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | lnHAPPY | Life ladder in natural logarithm | Scale | Gallup World Poll | |

| Economic growth | lnPCGDP | GDP per capita, Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) in natural logarithm | At constant 2017 international $ | World Development Indicators | +/− |

| Inflation | GDPDEF | GDP deflator | In annual % | World Development Indicators | +/− |

| Globalisation | lnTOP | Trade (% of GDP) in natural logarithm | In annual % | World Development Indicators | +/− |

| Corruption | lnPOC | Averaging the answer to two questions. (a) Is corruption widespread throughout the government or not? (b) Is corruption widespread within the business or not? | Scale | Gallup World Poll | − |

| Social support | lnSOS | It is the national average of binary (0/1) response to the question. If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not? | Scale | Gallup World Poll | + |

(1)

(1) (2)

(2)4.1 Panel corrected standard error (PCSE) model

The current study is based on a panel of 19 countries and a time period of 14 years. Panel data have common problems such as CSD, autocorrelation, and groupwise heteroskedasticity. Most of the studies used the Pooled Ordinary Least Square (POLS), fixed effects (FE), and random effects (RE) models to investigate the panel data. If assumptions of CSD, autocorrelation, and panel groupwise heteroskedasticity of panel data are violated, then traditional models, that is, POLS, FE, and RE, can produce biased and inefficient estimates. The sign of the coefficients may get changed if there is CSD, autocorrelation, and panel groupwise heteroskedasticity issues in the panel data. In the given context, researchers recommend feasible generalised least square method (FGLS) introduced by Parks (1967) and PCSE model given by Beck and Katz (1995). FGLS model can only be applied when the time period is higher than cross-sectional units (T > N) while PCSE can be used when N > T (Reed & Ye, 2011). In our study, cross-sectional units (19 countries) are higher than time period (14 years) and sample size is also small. Therefore, Prais–Winsten model with PCSE approach is applied to analyse the impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness. PCSE method has several advantages. First, the PCSE approach resolves CSD problems, autocorrelation, and panel groupwise heteroskedasticity issues (Marques et al., 2016). Second, this method removes the possibility of downward bias or upward biased in the standard error estimates (Schmitt, 2016). Thirdly, PCSE performs better in the short sample than the asymptotically efficient FGLS (Greene, 2003). Fourthly, PCSE has an advantage over FGLS as it does not underestimate variability in the panel errors (Beck, 2001). The PCSE method has been commonly used by various researchers recently in the literature (Dash et al., 2021; Kongkuah et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; Kumari, Kumar, & Sahu, 2021; Nathaniel et al., 2021).

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this section, the descriptive analysis, correlation, pre-estimation and post-estimation results are discussed. The correlation between the variables is shown in Table 2. Descriptive statistics of variables are presented in Table 3 and Table 4. The results of descriptive statistics revealed that the top five happiest EMEs are Mexico, Brazil, Czech Republic, Chile, and Argentina. The first five unhappiest EMEs are India, Egypt, South Africa, Philippines, and Hungary. However, in the group descriptive statistics, American EMEs have the highest value of happiness (6.321) as compared to Asian EMEs (5.448) and EMEA emerging countries (5.456). A minimum value of happiness is observed as 3.249 in the sample of Asian EMEs.

| Independent variables | lnPOC | lnSOS | lnTOP | lnPCGDP | GDPDEF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnPOC | 1 | ||||

| lnSOS | 0.090 | 1 | |||

| lnTOP | 0.248 | 0.279 | 1 | ||

| lnPCGDP | 0.051 | 0.651 | 0.464 | 1 | |

| GDPDEF | 0.026 | −0.086 | −0.441 | −0.119 | 1 |

| Happiness | Economic growth | Inflation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | |

| America | ||||||||||||

| Argentina | 6.339 | 0.303 | 5.793 | 6.776 | 23111.100 | 1112.586 | 20777.800 | 24647.800 | 27.451 | 11.478 | 13.741 | 51.508 |

| Brazil | 6.608 | 0.359 | 5.950 | 7.140 | 14644.590 | 826.430 | 12917.900 | 15800.000 | 6.851 | 1.857 | 3.285 | 8.779 |

| Chile | 6.371 | 0.358 | 5.698 | 6.844 | 22085.600 | 1920.379 | 18956.600 | 24258.700 | 4.474 | 3.163 | −0.053 | 12.162 |

| Colombia | 6.287 | 0.178 | 5.984 | 6.607 | 13004.960 | 1401.553 | 10693.300 | 14730.900 | 4.454 | 1.544 | 2.078 | 7.741 |

| Mexico | 6.725 | 0.365 | 6.222 | 7.443 | 18791.410 | 813.762 | 17194.700 | 19992.200 | 4.708 | 1.491 | 1.530 | 6.761 |

| Peru | 5.594 | 0.331 | 4.811 | 5.999 | 10961.930 | 1624.780 | 8017.250 | 12847.900 | 3.030 | 2.160 | 1.057 | 7.656 |

| Asia | ||||||||||||

| India | 4.491 | 0.561 | 3.249 | 5.348 | 4900.501 | 1098.109 | 3446.760 | 6754.290 | 6.028 | 2.763 | 2.280 | 10.526 |

| Indonesia | 5.228 | 0.220 | 4.815 | 5.597 | 9283.080 | 1549.631 | 6974.450 | 11812.200 | 7.484 | 5.212 | 1.605 | 18.150 |

| Malaysia | 5.800 | 0.301 | 5.339 | 6.322 | 22962.600 | 3206.498 | 18756.100 | 28350.600 | 2.646 | 3.862 | −5.992 | 10.389 |

| Pakistan | 5.412 | 0.579 | 4.414 | 6.929 | 4168.931 | 316.133 | 3836.490 | 4739.770 | 9.331 | 6.532 | 0.400 | 20.667 |

| Philippines | 5.225 | 0.472 | 4.589 | 6.268 | 6745.107 | 1202.777 | 5228.320 | 8908.180 | 2.980 | 1.954 | −0.587 | 7.549 |

| South Korea | 5.881 | 0.377 | 5.332 | 6.947 | 36545.110 | 4044.763 | 30022.500 | 42661.200 | 1.626 | 1.319 | −0.933 | 3.609 |

| Thailand | 6.102 | 0.390 | 5.476 | 6.985 | 15462.180 | 1811.488 | 12850.600 | 18463.100 | 2.380 | 1.578 | 0.195 | 5.134 |

| Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) | ||||||||||||

| Czech Republic | 6.598 | 0.292 | 6.250 | 7.279 | 35337.070 | 2529.905 | 32466.100 | 40314.200 | 1.627 | 1.333 | −1.425 | 3.524 |

| Egypt | 4.626 | 0.730 | 3.559 | 6.449 | 10355.820 | 768.979 | 8814.150 | 11763.300 | 12.766 | 5.068 | 6.246 | 22.933 |

| Greece | 5.520 | 0.535 | 4.720 | 6.647 | 31779.010 | 3813.545 | 28077.400 | 37924.200 | 0.781 | 2.000 | −2.352 | 4.345 |

| Hungary | 5.212 | 0.476 | 4.683 | 6.065 | 26895.190 | 2585.380 | 24276.700 | 32622.900 | 3.425 | 1.268 | 0.886 | 5.422 |

| Poland | 5.933 | 0.187 | 5.646 | 6.242 | 26163.390 | 3848.316 | 20118.200 | 33086.400 | 2.022 | 1.317 | 0.290 | 3.877 |

| Russia | 5.523 | 0.304 | 4.964 | 6.037 | 25144.110 | 1500.257 | 21824.200 | 27043.900 | 9.975 | 6.480 | 1.971 | 24.460 |

| South Africa | 4.868 | 0.417 | 3.661 | 5.346 | 12583.940 | 262.031 | 11924.100 | 12884.100 | 6.207 | 1.518 | 3.917 | 8.849 |

| Turkey | 5.366 | 0.327 | 4.872 | 6.129 | 23453.000 | 3539.642 | 18734.800 | 28298.900 | 9.034 | 3.190 | 5.402 | 16.439 |

| Globalisation | Corruption | Social support | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | |

| America | ||||||||||||

| Argentina | 32.227 | 5.816 | 22.486 | 40.945 | 0.844 | 0.032 | 0.755 | 0.885 | 0.905 | 0.020 | 0.862 | 0.938 |

| Brazil | 25.513 | 2.102 | 22.106 | 29.398 | 0.724 | 0.053 | 0.623 | 0.794 | 0.900 | 0.012 | 0.878 | 0.916 |

| Chile | 65.775 | 8.107 | 55.656 | 80.790 | 0.768 | 0.064 | 0.634 | 0.860 | 0.846 | 0.026 | 0.804 | 0.890 |

| Colombia | 37.401 | 1.706 | 34.265 | 39.641 | 0.850 | 0.037 | 0.763 | 0.898 | 0.894 | 0.014 | 0.871 | 0.914 |

| Mexico | 66.317 | 8.774 | 55.968 | 80.448 | 0.729 | 0.070 | 0.615 | 0.809 | 0.834 | 0.050 | 0.759 | 0.893 |

| Peru | 50.360 | 4.153 | 45.163 | 58.434 | 0.882 | 0.024 | 0.824 | 0.931 | 0.803 | 0.034 | 0.756 | 0.875 |

| Asia | ||||||||||||

| India | 47.189 | 5.724 | 40.019 | 55.794 | 0.832 | 0.050 | 0.752 | 0.908 | 0.606 | 0.054 | 0.511 | 0.707 |

| Indonesia | 46.983 | 6.777 | 37.303 | 58.561 | 0.931 | 0.040 | 0.861 | 0.973 | 0.794 | 0.055 | 0.675 | 0.905 |

| Malaysia | 151.508 | 24.734 | 123.091 | 202.577 | 0.833 | 0.047 | 0.740 | 0.894 | 0.824 | 0.032 | 0.770 | 0.871 |

| Pakistan | 31.249 | 3.252 | 25.306 | 35.682 | 0.799 | 0.065 | 0.677 | 0.884 | 0.570 | 0.087 | 0.373 | 0.690 |

| Philippines | 65.068 | 7.233 | 55.825 | 80.851 | 0.785 | 0.045 | 0.711 | 0.880 | 0.818 | 0.026 | 0.775 | 0.854 |

| South Korea | 85.885 | 11.921 | 70.652 | 105.566 | 0.808 | 0.041 | 0.718 | 0.862 | 0.791 | 0.026 | 0.738 | 0.827 |

| Thailand | 127.796 | 8.811 | 110.299 | 140.437 | 0.909 | 0.019 | 0.877 | 0.935 | 0.892 | 0.025 | 0.832 | 0.933 |

| Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) | ||||||||||||

| Czech Republic | 140.901 | 13.712 | 113.493 | 158.727 | 0.907 | 0.036 | 0.836 | 0.957 | 0.913 | 0.021 | 0.878 | 0.957 |

| Egypt | 48.282 | 11.952 | 30.247 | 71.681 | 0.919 | 0.152 | 0.684 | 1.217 | 0.719 | 0.059 | 0.619 | 0.809 |

| Greece | 61.315 | 7.490 | 47.744 | 74.385 | 0.898 | 0.048 | 0.824 | 0.959 | 0.816 | 0.052 | 0.687 | 0.891 |

| Hungary | 161.427 | 7.400 | 144.768 | 168.490 | 0.910 | 0.030 | 0.855 | 0.983 | 0.902 | 0.032 | 0.845 | 0.947 |

| Poland | 90.843 | 10.872 | 75.226 | 107.478 | 0.850 | 0.096 | 0.639 | 0.939 | 0.909 | 0.024 | 0.863 | 0.955 |

| Russia | 49.346 | 2.607 | 46.287 | 54.733 | 0.914 | 0.032 | 0.862 | 0.954 | 0.903 | 0.016 | 0.881 | 0.932 |

| South Africa | 61.202 | 4.319 | 55.418 | 72.865 | 0.839 | 0.030 | 0.791 | 0.904 | 0.866 | 0.038 | 0.788 | 0.917 |

| Turkey | 51.113 | 4.813 | 45.899 | 61.395 | 0.763 | 0.061 | 0.649 | 0.853 | 0.804 | 0.079 | 0.645 | 0.940 |

In EMEA emerging countries, happiness variability is highest. Per capita GDP varies from $3446.760 to $42661.200 in our sample. The average per capita GDP is maximum in EMEA emerging countries ($23963.940), followed by American EMEs ($17099.930) and Asia EMEs ($14295.360). There is significant variability in inflation as it varies from −5.992 to +51.508. Sample EMEA countries have a higher degree of globalisation since their average value of trade openness is 83.054%, followed by Asian EMEs (70.382%), and American EMEs (46.266%). The average value of corruption is recorded as the highest (0.875) in EMEA countries in comparison with Asian EMEs (0.842) and American EMEs (0.800). Among the three panels, American emerging countries have the highest value of social support. Country-wise descriptive statistics are shown in Table 4 to understand the nature of data across the countries.

Since the data used in the study is panel data, diagnostic tests need to be performed before estimating the data. A poolability test is used to check whether the data is poolable across the panels or not. The findings of the test reveal that data is not poolable across the countries. After the poolability test, Jarque Bera normality test is applied (see Table 5). The result reflects that data is normally distributed. After normality testing, it becomes important to check CSD, group-wise heterogeneity, and autocorrelation problems. The Wooldridge (2002) test is applied to find out the existence of autocorrelation between the error terms. Pesaran (2004) test is performed to detect CSD. Lastly, to check group-wise heteroscedasticity, Baum (2001) modified Wald test is used. The result of the pre-estimation diagnostic test is presented in Table 6. The results of these tests confirm that there is autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity and CSD problems in the data. Therefore, the PCSE model is applied in this study (Table 7).

| Panel | Obs. | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Jarque-Bera (probability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | ||||||

| Panel | 294 | 5.70 | 0.75 | 3.25 | 7.44 | 4.65 (0.10) |

| America | 84 | 6.32 | 0.48 | 4.81 | 7.44 | 4.11 (0.13) |

| EMEA | 112 | 5.46 | 0.72 | 3.56 | 7.28 | 0.03 (0.98) |

| Asia | 98 | 5.45 | 0.65 | 3.25 | 6.99 | 5.12 (0.08) |

| Economic growth | ||||||

| Panel | 294 | 18779.93 | 9672.72 | 3446.76 | 42661.20 | 11.97 (0.00) |

| America | 84 | 17099.93 | 4761.70 | 8017.25 | 24647.80 | 5.62 (0.06) |

| EMEA | 112 | 23963.94 | 8508.13 | 8814.15 | 40314.20 | 5.32 (0.07) |

| Asia | 98 | 14295.36 | 11250.93 | 3446.76 | 42661.20 | 18.44 (0.00) |

| Inflation | ||||||

| Panel | 294 | 6.16 | 6.92 | −5.99 | 51.51 | 2087.15 (0.00) |

| America | 84 | 8.50 | 9.91 | −0.05 | 51.51 | 212.30 (0.00) |

| EMEA | 112 | 5.73 | 5.29 | −2.35 | 24.46 | 45.51 (0.00) |

| Asia | 98 | 4.64 | 4.59 | −5.99 | 20.67 | 68.38 (0.00) |

| Globalisation | ||||||

| Panel | 294 | 71.32 | 40.63 | 22.11 | 202.58 | 68.51 (0.00) |

| America | 84 | 46.27 | 16.90 | 22.11 | 80.79 | 5.38 (0.07) |

| EMEA | 112 | 83.05 | 42.66 | 30.25 | 168.49 | 18.24 (0.00) |

| Asia | 98 | 79.38 | 43.48 | 25.31 | 202.58 | 10.71 (0.00) |

| Corruption | ||||||

| Panel | 294 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.62 | 1.22 | 23.07 (0.00) |

| America | 84 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.62 | 0.93 | 6.48 (0.04) |

| EMEA | 112 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 0.64 | 1.22 | 30.36 (0.00) |

| Asia | 98 | 0.84 | 0.07 | 0.68 | 0.97 | 1.91 (0.39) |

| Social support | ||||||

| Panel | 294 | 0.82 | 0.10 | 0.37 | 0.96 | 181.02 (0.00) |

| America | 84 | 0.86 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 9.28 (0.01) |

| EMEA | 112 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 29.33 (0.00) |

| Asia | 98 | 0.76 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.93 | 13.86 (0.00) |

- Note: Value in the parenthesis denotes the p values.

| Test statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test name | Panel | America | Asia | EMEA | |

| Poolability test | F | 19.68a | 11.18a | 14.39a | 9.74a |

| Wooldridge test for autocorrelation | F | 27.801a | 40.645a | 24.124a | 6.487b |

| Pesaran test for cross sectional dependence | Chi2 | 0.179 | 4.953a | 0.908 | 2.114b |

| Modified Wald test for group-wise heteroscedasticity | Chi2 | 1595.67a | 6.67 | 32.33b | 536.54c |

- Note: a, b, and c denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance respectively.

| Variables | Full sample | America | Asia | EMEA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| lnPCGDP | 0.054a | 0.010 | 0.159a | 0.000 | 0.032 | 0.168 | 0.148a | 0.000 |

| (0.021) | (0.032) | (0.023) | (0.041) | |||||

| GDPDEF | 0.001 | 0.360 | −0.002b | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.233 | 0.000 | 0.872 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||

| lnPOC | −0.200a | 0.006 | −0.313a | 0.000 | −0.239b | 0.054 | −0.081 | 0.501 |

| (0.073) | (0.067) | (0.124) | (0.120) | |||||

| lnSOS | 0.365a | 0.000 | 0.190 | 0.166 | 0.374a | 0.000 | 0.128 | 0.360 |

| (0.072) | (0.138) | (0.096) | (0.139) | |||||

| lnTOP | −0.004 | 0.849 | −0.054b | 0.046 | 0.017 | 0.507 | −0.014 | 0.857 |

| (0.022) | (0.027) | (0.025) | (0.078) | |||||

| Constant | 1.250a | 0.000 | 0.470 | 0.134 | 1.374a | 0.000 | 0.256 | 0.641 |

| (0.188) | (0.314) | (0.202) | (0.549) | |||||

- Note: a, b, and c denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance respectively. Value in the parenthesis denotes the standard error.

5.1 Aggregate panel results

The sample of 21 EMEs is chosen for the study to find out the impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness. Results of the aggregate panel are presented in Table 7. Estimates of the result revealed that the per capita GDP coefficient is positive and significant at 5% level of significance. It implies that 1% increase in per capita GDP results in an approximate increment of 0.05% in the happiness level of EMEs. This result is similar to Kenny (1999) and Howell and Howell (2008). An increase in production and growth can provide numerous choices to people and thus further enhances their happiness. Also, Ahuvia and Friedman (1998) stated that increased GDP fulfils the material needs along with promoting health, women empowerment, education, and democracy. A similar outcome is found by De Neve et al. (2018) that negative economic growth in the business cycle negatively impacts SWB.

In the aggregate study, the coefficient of corruption is negative and significant at 1% level of significance. When there is 1% rise in perception of corruption, happiness decreases by 0.20% in EMEs. This finding supports the previous studies (Helliwell & Huang, 2008; Li & An, 2020; Wu & Zhu, 2016), which found that corruption reduces happiness. In the recent literature, Li and An (2020) reported that happiness would be decreased by 0.23 points when government becomes corrupt by 10 points. Our finding is similar to Achim et al. (2019), who found that perception of corruption reduces the happiness of high-income countries more than low-income countries.

Moreover, the coefficient of social support is positive and significant at 1% level of significance. It means that 1% rise in the level of social support results in about 0.365% increase in happiness in the sample countries. This finding is clearly evident from the past literature (Bartolini et al., 2013; Bartolini & Sarracino, 2014; Chang, 2009) in which they reported a positive association between social support and happiness. In recent literature, Hori and Kamo (2018) found the positive impact of social support on happiness in China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Majeed and Samreen (2020) extracted data from the World Value Survey and found that social capital positively contributes to happiness in 89 countries. However, our findings contradict Ram (2010), who found that social capital does not result in happiness in transition countries.

5.2 Group-wise analysis

The aggregate dataset of 21 EMEs is categorised into three regional groups for exploring the impact of socioeconomic conditions on happiness. These groups are (a) America, (b) Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA), and (c) Asia. The results of group-wise analysis are presented in Table 7.

5.2.1 American group

In the EMEs of America, it is found that per capita GDP has a positive impact on happiness. The coefficient of per capita GDP shows 1% increase in GDP per capita has about 0.159% positive impact on happiness. This finding is analogous to Zengrui et al. (2018), who concluded that economic growth has a stronger positive impact on life satisfaction in Latin America than in East Asia and Pacific Countries. In a recent study, Dávalos and Vargas-Hérnandez (2020) found a similar result that economic growth has a positive impact on subjective wellbeing in 17 Latin American Countries.

For American EMEs, the coefficient of inflation is negative and significant at 5% level of significance. The coefficient of inflation reveals that happiness reduces by 0.2% with 1% rise in inflation. Ruprah and Luengas (2011) also found a similar result, that is, inflation reduces happiness in Latin American countries.

Further, the perception of corruption is a negative determinant of happiness in EMEs of America. 1% rise in perception of corruption reduces happiness by 0.313%. This result might be possible that people are educated and have awareness regarding their rights. Thus, corruption cases are widely reported. However, Zengrui et al. (2018) found a U-shaped link between perception of corruption and SWB in Latin American countries.

Moreover, trade openness has a negative impact on happiness. There is 0.054% decline in happiness with 1% rise in trade openness. It might be possible that trade openness in the form of massive import penetration has not reduced poverty and regional inequalities (Castilho et al., 2012; Rivas, 2007). The lack of preparedness to absorb the shock and the sudden opening of the market has resulted in the increased unemployment and income inequalities (Maurizio, 2009).

5.2.2 Europe, Middle East, and Africa group

In EMEA's EMEs group, only per capita GDP is found to be positive and significant at 1%. Happiness increases by 0.148% with 1% rise in economic growth. Increased GDP through oil revenues is used for employment, safety net, health, housing, education, and recreation which has increased happiness in these countries (D'raven & Pasha–Zaidi, 2015). Our findings contradict the studies of Ali et al. (2020) and Mignamissi and Kuete (2021) who found that oil and gas rents have a negative impact on happiness due to the volatility of oil prices and ineffective income distributive policies.

5.2.3 Asian group

For Asian EMEs, the coefficient of social support is positive and statistically significant at 1% level of significance. It implies that happiness rises by 0.374% with 1% rise in social support. Recently, Tokuda et al. (2017) reported that people are happier in those Asian countries where there is a higher level of social trust. Yuen and Chu (2015) found that cultural and social values matter for Asians. Moreover, corruption is found as a negative determinant of happiness at a 5% level of significance. With 1% rise in corruption, happiness reduces by 0.239%. A similar result is found by Chang and Chu (2006) that corruption deteriorated institutional trust in Japan, Philippines, South Korea, Thailand, and Taiwan.

5.3 Country-wise analysis

Country-wise analysis is done to identify which socioeconomic variable is essential in determining each country's happiness. Results of the country-wise socioeconomic determinants of happiness are presented in Tables 8, 9, and 10. In the case of Brazil, per capita income positively affects happiness. Due to high economic growth and the successful implementation of socioeconomic policies in the 20th century, inequality and poverty level have been reduced (Loubser & Steenekamp, 2017). However, for Indians, per capita income negatively influences happiness. This finding supports the result of Lakshmanasamy and Maya (2020), who found that happiness is not increased with the increased income across Indian states. Inequalities in life satisfaction and income, regional differences, increasing aspirations, and status consciousness are the possible causes of reduced happiness in India.

| Countries | lnPCGDP | GDPDEF | lnPOC | lnSOS | lnTOP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | |

| Argentina | 0.131 | 0.299 | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.476 | 0.306 | 0.557 | 0.477 | −0.067 | 0.078 |

| (0.662) | (0.287) | (0.120) | (0.243) | (0.390) | ||||||

| Brazil | 0.476a | 0.194 | 0.005 | 0.006 | −0.169 | 0.192 | 0.955 | 0.913 | −0.100 | 0.146 |

| (0.014) | (0.392) | (0.378) | (0.295) | (0.492) | ||||||

| Chile | 0.304 | 0.321 | −0.002 | 0.005 | −0.567c | 0.323 | 0.092 | 0.514 | −0.311 | 0.200 |

| (0.344) | (0.654) | (0.080) | (0.858) | (0.121) | ||||||

| Colombia | 0.042 | 0.086 | −0.008 | 0.005 | 0.029 | 0.182 | 0.171 | 0.420 | 0.116 | 0.140 |

| (0.629) | (0.119) | (0.873) | (0.684) | (0.407) | ||||||

| Mexico | −0.978 | 0.639 | −0.005 | 0.010 | −0.277 | 0.218 | 0.155 | 0.320 | 0.294 | 0.232 |

| (0.126) | (0.628) | (0.203) | (0.628) | (0.205) | ||||||

| Peru | 0.278a | 0.068 | −0.001 | 0.005 | −0.670c | 0.356 | −0.361 | 0.255 | −0.052 | 0.126 |

| (0.000) | (0.857) | (0.060) | (0.157) | (0.678) | ||||||

- Note: a, b, and c denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance respectively. Value in the parenthesis denotes the p value.

| Countries | lnPCGDP | GDPDEF | lnPOC | lnSOS | lnTOP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | |

| India | −0.506a | 0.127 | 0.013 | 0.009 | −0.692 | 0.441 | 0.207 | 0.151 | 0.235 | 0.207 |

| (0.000) | (0.168) | (0.117) | (0.169) | (0.255) | ||||||

| Indonesia | −0.081 | 0.105 | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.008 | 0.269 | 0.459a | 0.143 | −0.072 | 0.126 |

| (0.441) | (0.857) | (0.976) | (0.001) | (0.566) | ||||||

| Malaysia | −0.114 | 0.277 | 0.003 | 0.003 | −0.044 | 0.213 | 0.311 | 0.296 | −0.037 | 0.253 |

| (0.679) | (0.285) | (0.836) | (0.294) | (0.884) | ||||||

| Pakistan | −1.163a | 0.453 | 0.001 | 0.003 | −0.402c | 0.218 | 0.666a | 0.138 | 0.041 | 0.271 |

| (0.010) | (0.782) | (0.065) | (0.000) | (0.879) | ||||||

| Philippines | 0.533a | 0.064 | −0.014a | 0.004 | 0.210 | 0.179 | −0.534c | 0.304 | 0.179a | 0.057 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.242) | (0.079) | (0.002) | ||||||

| South Korea | 0.190b | 0.086 | −0.011 | 0.008 | 0.173 | 0.180 | 1.137a | 0.281 | 0.302a | 0.068 |

| (0.028) | (0.163) | (0.334) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||

| Thailand | 0.397a | 0.108 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.649 | 0.738 | 1.176a | 0.341 | 0.550b | 0.243 |

| (0.000) | (0.840) | (0.379) | (0.001) | (0.023) | ||||||

- Note: a, b, and c denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance respectively. Value in the parenthesis denotes the p value.

| Countries | lnPCGDP | GDPDEF | lnPOC | lnSOS | lnTOP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Coef. | Std. Er. | |

| Czech Republic | 0.096 | 0.232 | 0.005 | 0.004 | −0.699a | 0.296 | 0.082 | 0.342 | 0.026 | 0.081 |

| (0.677) | (0.277) | (0.018) | (0.811) | (0.748) | ||||||

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | −1.034 | 0.640 | −0.008 | 0.007 | 0.059 | 0.217 | −0.047 | 0.396 | 0.093 | 0.180 |

| (0.106) | (0.267) | (0.786) | (0.906) | (0.604) | ||||||

| Greece | 0.470 | 0.359 | −0.002 | 0.019 | −0.858b | 0.390 | 0.195 | 0.196 | −0.069 | 0.207 |

| (0.190) | (0.922) | (0.028) | (0.321) | (0.738) | ||||||

| Hungary | 1.062a | 0.096 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.012 | 0.228 | −0.693a | 0.254 | −0.388b | 0.180 |

| (0.000) | (0.921) | (0.958) | (0.006) | (0.031) | ||||||

| Poland | −0.172 | 0.116 | −0.001 | 0.005 | −0.251a | 0.084 | 0.250 | 0.276 | 0.203 | 0.169 |

| (0.138) | (0.815) | (0.003) | (0.366) | (0.230) | ||||||

| Russia | 0.725a | 0.189 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.269 | 0.307 | 1.311a | 0.495 | −0.018 | 0.218 |

| (0.000) | (0.188) | (0.381) | (0.008) | (0.936) | ||||||

| South Africa | −1.518 | 1.047 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 1.187b | 0.601 | 0.130 | 0.537 | 0.189 | 0.389 |

| (0.147) | (0.986) | (0.048) | (0.809) | (0.627) | ||||||

| Turkey | −0.291a | 0.090 | 0.008 | 0.005 | −0.273b | 0.135 | 0.545a | 0.103 | −0.289 | 0.211 |

| (0.001) | (0.108) | (0.043) | (0.000) | (0.171) | ||||||

- Note: a, b, and c denotes 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance respectively. Value in the parenthesis denotes the p value.

For Chile, the Czech Republic, Greece, and Poland, corruption reduces happiness. This result is evident in Lizal and Kocenda (2001) study who found that ineffective anti-corruption policies, patronage, and nepotism contribute to corruption in Chile. Greece has a higher corruption level among the sample of European emerging countries. Katsios (2006) also found a similar result that strict regulation and high administrative compliance costs had resulted in the demand for a high level of bribery in Greece. Similarly, McManus-Czubińska et al. (2004) reported that polish citizens lack trust in government officers. In Hungary, per capita GDP has a positive impact on happiness. At the same time, trade openness and social support are negatively associated with happiness. A similar result was reported by Lelkes (2006), people care more about economic growth in Hungary, while social support offered by the churches does not influence people's happiness. In contrast to this finding of Hungary, social support has a positive impact on Indonesians. Despite the existence of different ethnic groups, there is tolerance, security, and willingness to help, which has enhanced the Indonesian people's happiness (Rahayu, 2016).

In the case of Pakistan, the negative coefficient of per capita GDP is found. This finding is similar to the study of Shahbaz and Aamir (2008), who found that Pakistan's higher economic growth has not been converted into higher happiness due to less decline in poverty, highly skewed income distribution, and presence of upper-echelon. Our findings contradict with Hasan (2016), who concluded that happiness has increased due to increment in income and the existence of no income adaptation in Pakistan from 1998–2001. However, trade openness positively influences happiness in Pakistan. Our finding is similar to the study of Shahbaz and Aamir (2008), who found that trade has increased happiness in Pakistan. In Peru, the per capita GDP brings happiness, while corruption deteriorates it. The suicide of the Peruvian president in the corruption scandal drawn attention to its weak institutions (Nureña & Helfgott, 2019). Per capita GDP and trade openness act as a positive determinant of happiness in the Philippines. This country went into transition by adopting globalisation as a mechanism of economic growth, which has enhanced the wellbeing of the people. At the same time, inflation and social support are the negative determinants of happiness in the Philippines. For Russia, both social support and per capita GDP has a positive impact on happiness. Russia has experienced an economic crisis in 1998, which resulted in increased poverty and reduced satisfaction levels. Our result is similar to the findings of Schyns (2001), who found a positive impact of economic growth on happiness for Russia. For South Africa, corruption has a positive impact on happiness. This result might be possible due to the prevalence of grease the wheel hypothesis as bribery can help people in negotiating with the officials to get their work done quickly. However, this result contradicts the findings of Sulemana et al. (2016), who found that wellbeing gets reduced by corruption in Sub-Saharan African countries. In South Korea and Thailand, per capita GDP, trade openness, and social support positively influence happiness. This finding supports the result of Lim et al. (2020), who reported that South Korea being a techno-advanced country, has a high level of happiness because of a high economic growth level through trade openness. For Thailand, social support is a positive determinant of happiness. This finding is similar to the study of Senasu and Singhapakdi (2018). Buddhism culture is embedded in Thailand, which is based on the philosophy of morality and cooperation (Winzer et al., 2018). Lastly, per capita GDP and corruption reduces happiness in Turkey, while social support positively impacts it. Our result supports the study of Ekici and Koydemir (2014), who found that social capital, such as faith in institutions and membership in voluntary organisations positively affects the happiness of Turkish people. The summary of country-wise socioeconomic determinants of happiness is reported in Table 11.

| Country | Significant positive determinants of happiness | Significant negative determinants of happiness |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | Per capita GDP | |

| Chile, Czech Republic, Greece, and Poland | Perception of corruption | |

| Hungary | Per capita GDP | Trade openness and Social support |

| India | Per capita GDP | |

| Indonesia | Social support | |

| Pakistan | Social support | Perception of corruption and Per capita GDP |

| Peru | Per capita GDP | Perception of corruption |

| Philippines | Per capita GDP and Trade openness | Inflation and Social support |

| Russia | Per capita GDP, Social support | |

| South Africa | perception of corruption | |

| South Korea and Thailand | Per capita GDP, Social support, and trade openness | |

| Turkey | Social support | Per capita GDP and perception of corruption |

6 CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The present study examines the impact of socioeconomic variables on happiness in a panel of 21 EMEs and three sub-categories of EMEs during 2006–2019. PCSE model is adopted to overcome the problem of panel group-wise heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and CSD in the study. The findings reveal that economic growth and social support play a positive role in determining happiness in a panel of 21 EMEs, while corruption deteriorates happiness. Moreover, in American and Europe, Middle East and African EMEs, economic growth positively impacts happiness. Corruption is found to be a negative determinant of happiness in American and Asian EMEs. Inflation and globalisation are found as negative determinants of happiness in American EMEs. On the basis of the findings of our study, it can be suggested to the policymakers of the sample American emerging countries that (a) corruption should be taken as a matter of concern for the happiness of people by strengthening the existing anti-corruption institutions, (b) inflation should be under control to enhance the happiness level in these countries, and (c) interests of adversely affected people from globalisation in American emerging economies should be protected. For the EMEA countries, maintaining a stable growth rate is required to sustain their happiness. For the sample of Asian EMEs, a lower level of corruption is essential for determining happiness. Substantial social capital and community participation approach can increase the level of happiness in the sample Asian EMEs. There is a need for coordination among various departments of government agencies regarding the effective implementation of anti-corruption policies in Asian EMEs. Overall, this study advocates that in the rapidly changing paradigm, there is a prerequisite for strong economic, political, and social institutions for increasing happiness level in the selected EMEs of the world.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Neha Kumari and Pushp Kumar thankfully acknowledges IIT Bhubaneswar for providing MHRD Fellowship for his PhD and the present work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Neha Kumari: Conceptualization; Methodology; Data analysis; Writing – Original Draft. Dukhabandhu Sahoo: Methodology. Pushp Kumar: Data analysis. Naresh Chandra Sahu: Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review and Editing

Endnotes

Biographies

Miss Neha Kumari is currently pursuing Ph.D. at School of Humanities, Social Sciences, and Management, Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar, India. Her research interests include Economics of Happiness, Development Economics, Applied Econometrics, and Environmental Economics.

Dr. Naresh Chandra Sahu is an Assistant Professor of Economics at School of Humanities, Social Sciences, and Management, Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar, India. His research interests include Environmental Economics, Natural Resource Management, Mineral Economics, Valuation of Natural Resources, Environmental Impact Assessment, Climate Change, Rural Development, Economics of Happiness, Finance and Insurance.

Dr. Dukhabandhu Sahoo is an Assistant Professor of Economics at School of Humanities, Social Sciences, and Management, Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar, India. His research interests include Development Economics, Open Macroeconomics, Environmental and Natural Resource Economics, Issues relating to the Social Sector, Public Policies, and Applied Econometrics.

Mr. Pushp Kumar is currently pursuing Ph.D. at School of Humanities, Social Sciences, and Management, Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar, India. His research interests include Economics of Climate Change, International Trade, Applied econometrics, and Environmental Economics.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors