Corruption and bank efficiency: Expanding the ‘sand or grease the wheel hypothesis’ for the Gulf Cooperation Council

Abstract

We draw upon the broader theoretical framework of rent-seeking to empirically analyze the impact of corruption on the efficiency of the banking industry in the Gulf Cooperation Council. We have used various databases, including Bankscope, World Bank, and Transparency International, to gather Bank-specific and macro-economic data for 77 banks covering the period 2005–2014. We perform ordinary least square (OLS) and generalised methods of moments regression (GMM) using a balanced panel and find (1) Islamic banks as less efficient and stable as compared to conventional banks in the GCC region, (2) corruption has a negative (positive) impact on Islamic (conventional) banks' stability. Our findings provide support for the ‘sand the wheel’ hypothesis of corruption for Islamic banks. This finding supports the view that under the current weak governance structures and complex policy framework, corruption acts as an ‘escape hatch’ for conventional banks. Our empirical findings could pave the way for further policy reform for the banking sector in the GCC region.

1 INTRODUCTION

In a corrupt society, firms find it profitable to avoid normal administrative processes and resort to underground means. This tendency wanes states the capacity to collect revenues required for providing essential public goods, including efficient law and order (Aghion et al., 2016). Weak law and order, coupled with insecure property rights, amplifies corruption and discourages foreign capital inflows (Lambsdorff, 2003). This welfare-reducing impact of corruption is commonly referred to as the ‘sand or grease the wheel’ hypothesis (Méon & Weill, 2010; Méon & Sekkat, 2005; Sharma & Mitra, 2015).

On the contrary, Bhagwati (1982) shows that in an already distorted market, corruption, or rent-seeking (Bhagwati terms it ‘directly unproductive profit-seeking’), may lead to a welfare-enhancing effect. Bardhan (1997) refers to such an environment as ‘the second-best world’, characterised by policy-induced distortions such as pervasive and cumbersome regulations. Huntington (1968) argues that a higher level of corruption can improve growth bypassing bureaucratic processes. Blessed by the gift of natural resources, economies in the GCC countries have been relying heavily on hydrocarbon products, which accounts for almost half of the total gross domestic product (GDP). Corruption is one obstacle that may hinder the financial development of the GCC region.

The effect of corruption on financial development is inconclusive. Moreover, this issue remains largely unexplored in the context of GCC countries. In particular, there is a limited number of studies (Mohamed et al., 2021; Saif-Alyousfi & Saha, 2021; Saw et al., 2020) that investigate the diverse impact of corruption on bank efficiency with a theoretical perspective. The primary objective of this paper is to provide empirical evidence on the impact of corruption on the efficiency of the GCC banking sector. More specifically, we attempt to test the ‘sands or grease the wheel’ hypothesis for the GCC banking sector. In the process, we collect secondary data from various databases such as Bankscope for bank-specific data, World Bank database for macroeconomic data, and Transparency International for the country-level corruption data.

The timeliness of the research is crucial, given the backdrop of the GCC countries ongoing political and economic maladies. The current research expects to provide clues for the region to set its future reforms agenda in the financial sector. Third, the Islamic finance industry has grown rapidly in the GCC region, accumulating about 35% of the total assets of banking industries in 2007 (Srairi, 2010). The comparative study between the two types of banking operations (i.e., Islamic and conventional), which remains wholly ignored in contemporary literature, will provide an extra dimension for policy options.

We make three unique contributions. First, our results contribute to reducing the gaps in the literature on corruption and financial development. Since the existing literature is inconclusive, we expect to provide additional evidence and the factors through which corruption affects financial development. Second, we examine the impact of corruption on banks' efficiency in the GCC countries, which is limited in supply. Unlike previous studies, which mainly attribute the bank's inefficiency to internal factors, including management myopia and technical inefficiency, this study considers both internal and external factors in examining the bank's inefficiency.

We structure the rest of the paper as follows: Section 2 discusses the rent-seeking theory that encompasses the broader concept of corruption. Section 3 presents the methodological aspects of the study, which covers sample selection, variable definition leading to the econometric model development for empirical analysis. In Section 4, we discuss the efficiency of the banking section before moving toward the theoretical discussion that leads toward hypothesis development. We explain empirical results in Section 5, discuss the results in Section 6, while the final section summarises and concludes the study findings.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

GCC countries have been able to establish and sustain monarchies in all member states. Soon after ending the prolonged period, the Arab states established a kingdom or sultanate. The restoration of social stability in the GCC region proves the concentration of power at the centre. State society relation is hierarchical, where an administrator at the top governs the society through a mutual social contract. GCC states possess a durable power to penetrate society. Hence, rent-seeking competition is not pervasive, which keeps the rent-seeking cost low.

Especially after the event of the Arab Spring, the region has faced tremendous pressure from different societal groups internally and externally. Internal forces have taken various forms, including popular mobilisation and social discontent, resulting in economic handouts, patronage, limited political and economic reforms (Colombo, 2012). Although GCC states have tactically managed such challenges without much social chaos, which shows their resilience to tackle adverse internal political circumstances, the social contract has been loosened since then. Rougier (2016) offers by analysing various data that after the Arab Spring, authoritarianism that characterises the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has been vanished for very high levels due to social transformation. Such a level of authoritarianism may entail a negative rent-seeking outcome.

Ramanathan (2007) reports improvement in MPI among banks in Bahrain and records the highest reduction in productivity among selected banks in Qatar. Saw et al. (2020) report a higher level of efficiency for both Islamic and conventional banks in Qatar. Such results complement the findings of Grigorian and Manole (2005), as their study found banks in Bahrain with a higher level of technical efficiency as compared to other GCC countries. Aghimien et al. (2016) investigated the efficiency level of banks operating in the Gulf region and highlighted the impact of corruption on the efficiency of baking operations in the region.

Kamarudin et al. (2017) makes a unique contribution by comparing the efficiency of foreign and domestic banks in Southeast Asian countries and conclude that foreign-owned banks demonstrate a higher level of efficiency as compared to domestic banks. Alqahtani et al. (2017) find domestic banks in the GCC region are more cost-efficient than foreign banks. Kamarudin et al. (2016, 2018) provide empirical evidence that control of corruption enhances the revenue efficiency of both Islamic and conventional banks in the GCC region. Furthermore, Islamic banks in the GCC region suffers from financial turmoil caused by the subprime crisis (Al-Gasaymeh, 2016; Belanès et al., 2015; Mohanty et al., 2016).

3 THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

Corruption was a widely discussed phenomenon in the literature of development economics in the 1990s (see, e.g., Bardhan, 1997; Easterly & Levine, 1997; Gray & Kaufmann, 1998; Khan, 1998; Mauro, 1998; Rose-Ackerman, 1998; Shleifer & Vishny, 1993). Most studies, however, found evidence that corruption deteriorates economic development. Mauro (1995), analysing international data, shows that corruption hinders investment and lowers economic growth. Corruption increases uncertainty in an economy, leading to higher transaction costs (Anokhin & Schulze, 2009). Also, corruption leads to inefficient economic outcomes because it influences the misallocation of scarce resources, encourages rent-seeking, and distorts sectoral priorities and technology choices (Zhang & Barnett, 2014).

Lui (1985) provides empirical evidence on the positive impact of corruption on efficiency through the optimal allocation of available resources. Subsequently, the mainstream literature on corruption has extended to various branches. For instance, literature examining the impact of corruption on financial development is comparatively new. Bougatef (2017) finds that corruption reduces bank profitability by diverting funds to undeserving projects. Tran et al. (2020) confirm such findings in the context of Vietnam.

On the other hand, Treisman (2000) demonstrates that corruption eventually finds a way out to disrupt efficiency in jurisdictions with higher levels of corruption. In developing countries, Song et al. (2020) confirm the findings of Treisman (2000). However, Cherif and Dreger (2016) provide further evidence supporting the grease the wheel hypothesis. Wei and Kong (2017) discuss the influence of corruption on bank loans. Kunieda et al. (2016) confirm the adverse impact of corruption on economic growth through financial development.

Ariss et al. (2007) reported a decline in the overall efficiency scores of about 78% of the selected samples. The basic idea of corruption can be derived from the traditional principal-agent model where the public is considered the principal, and officials serve as agents. Corruption takes place when agents- who are entrusted with the task of enhancing public welfare- resort to some sort of malfeasance for their benefits (Bardhan, 1997; Lambsdorff, 2002). In this principal-agent relation, principals strive to maximise public welfare, whereas agents attempt to augment their benefits by trespassing the existing rules and colluding with third parties.

In this equation, third parties are likely to seek preferential treatment provided by government officials or politicians in exchange for some unique means such as bribes and lobbying (Aidt, 2016). Diverting economic inputs from the actual production process for such non-productive means is often accompanied by reduced welfare for societies. Such modelling of corruption conforms to the welfare analysis of rent-seeking (see, e.g., Khan 1999). Thus, we apply the rent-seeking model to analyze the welfare impact of corruption on societies.

Tullock (1967) initiated an academic discussion on rent-seeking. His seminal work on rent-seeking shows the negative aspect of resources un-utilisation on society. In line with this tradition, a situation in which rent-seeking benefits outweigh the rent-seeking cost, the ultimate result is the ‘rent creation’ or positive effect on economic activities. In contrast, if the cost is higher than the benefit, rent-dissipation is the eventual result leading to an overall welfare loss. Thus, the welfare effect of corruption depends on its relative cost and outcome. Society benefits from such a state because buyers of such political goods ensure that their rights bought from the central authority are secured. When the question comes about the security of rights in a rent-seeking society, power centralisation is crucial for social welfare (Shleifer & Vishny, 1993).

In contrast, multiple monopolists sell their complementary political goods independently in jurisdictions with weaker and less centralised political leadership. Because political leadership cannot exert sufficient power on bureaucratic agencies, officials act as independent monopolists to maximise their benefits and push up the price even though it leads to an overall decline in demand for such goods. The striking features of this state are that those who are purchasing political goods are never sure if other monopolists will threaten the rights they have bought from an individual monopolist. The weaker the political leadership controls the more significant the scope for independent and non-cooperative monopolists to extract their benefits, leaving the society on the verge of overall loss (MacIntyre, 2000). Based on the above discussion, we develop the following hypothesis:

H1.The impact of corruption on the efficiency of GCC banks could not be known a priori.

4 METHODOLOGY

4.1 Sample selection

We have selected 76 banks, including 49 conventional banks and 28 Islamic banks in six GCC countries, namely Bahrain (17), Kuwait (8), Oman (6), Qatar (10), United Arab Emirate (24), and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (12). We choose to study commercial banks in this study. We have collected bank-specific data from the Bankscope database between 2005–2014 (description of the sample is provided in Appendix A). We have attempted to include recent data for the banks operating in the GCC region to make reliable estimates and inferences. However, due to the unavailability of the Bankscope database since 2016, we were unable to include bank-specific data until 2019. We include banks with data available for at least two in this study (please see Table A1 in Appendix A). We have collected macroeconomic data from the World Bank database and the Transparency International website.

4.2 Measurement of variables

4.2.1 Measurement of bank efficiency

- Bank Orientation – serves as a proxy of the business model for the banking sector. Islamic and conventional banks operate based on unique business models. Beck et al. (2013) suggest that Islamic banks' earnings from fee-based income are higher than conventional banks. We use the ratio of fee-based income to total assets as a proxy for bank orientation.

-

Efficiency – is estimated using Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) for both clusters of banks. SFA requires the identification of inputs and output prices of banks. There are two widely used methods of SFA, which include the asset approach and intermediation approach. We use the intermediation approach of SFA following Miah and Uddin (2017) in a similar study. Fries and Taci (2005) adopted a similar approach in inter-bank studies. Loans and securities are used as outputs, while inputs include the cost of labour and capital to measure the cost efficiency of banks.

It is essential to address that past studies also used data envelopment analysis (DEA) to measure bank efficiency (Kamarudin et al., 2018; Loong et al., 2017; Sufian & Kamarudin, 2014a). DEA method considers that any deviation of the observation from its projection over the efficiency frontier represents inefficiency, but without the presence of a random effect. As such, we did not consider the DEA method to measure bank efficiency as it is often difficult to specify inefficiency using a DEA method Avkiran (2006). Such shortcomings of the DEA method could be addressed by applying the stochastic frontier approach (SFA) which allows for the specification of the production function and accounts for external factors affecting efficiency (Zeineb & Mensi, 2018).

- Stability – is measured using a z-score. Z-score has become a popular measure of bank stability in recent studies (Beck et al., 2013). We calculate Z-score as

, where ROA is the return on asset, CAR is total equity/total asset and

, where ROA is the return on asset, CAR is total equity/total asset and  is the standard deviation of ROA for a 3 year period. Kabir et al. (2015) recommend a three-year window to capture significant variations in capital and profitability.

is the standard deviation of ROA for a 3 year period. Kabir et al. (2015) recommend a three-year window to capture significant variations in capital and profitability.

4.2.2 Measurement of corruption

We use the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) published by Transparency International as a measure of the level of corruption in the selected GCC countries. CPI scores provided by Transparency International measures the level of corruption using a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). As a result, the higher the score provided by the original CPI, the lower is the level of corruption. The new scale is introduced in 2012 because, until 2011, CPI scores were measured using a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 10 (very clean). Since our sample covers data from 2005 to 2014, we have applied the following measurement to adjust CPI scores from two different scales following Bougatef (2016):  . In the next stage, we adjust CPI score using the following measurement:

. In the next stage, we adjust CPI score using the following measurement:  (Park, 2012) to reverse the meaning of the index. Therefore, a high score in the adjusted CPI score indicates a higher level of corruption, following the scale of 0 (very clean) to 10 (highly corrupt). We present CPI scores and corruption ranking of GCC Countries in Table A2 (Appendix A).

(Park, 2012) to reverse the meaning of the index. Therefore, a high score in the adjusted CPI score indicates a higher level of corruption, following the scale of 0 (very clean) to 10 (highly corrupt). We present CPI scores and corruption ranking of GCC Countries in Table A2 (Appendix A).

4.2.3 Control variables

We include various types of control variables in our regression model to explain variation in bank efficiency. At the bank level, we have firm size, asset growth, leverage, and capital asset ratio. We measure firm size with the logarithm of the total asset of a bank. Large banks have less credit risk (Haq & Heaney, 2012) due to increased risk management skills compared to smaller banks (Wang et al., 2015). Therefore, we expect larger banks to have better efficiency than smaller banks. Srairi (2016) found a positive impact of leverage and bank efficiency in the GCC region. Therefore, we include leverage as a control variable in the study, measured as a ratio of equity over the total asset, following Kabir et al. (2015). Following Srairi (2019), we include asset growth to control the bank growth and development strategy. The capital asset ratio has been recently introduced by İncekara and Çetinkaya (2019) to control the capital adequacy requirements for the banking sector in the GCC region.

Following several studies, we use a range of country-level control variables in this study that may impact bank efficiency. Country-level controls include GDP growth, inflation, country governance, and banking sector development. We introduce the GDP growth rate to control economic development (Lassoued, 2018). We also control inflation following Lassoued (2018). Srairi (2019) argued that banking sector development could influence bank efficiency. Country-level governance (Chen et al., 2015; Hussain, Kamarudin, et al., 2020; Hussain, Kot, et al., 2020) is measured using the six indicators developed by the World Bank. Finally, country*year is used in the regression model to test for the broadest possible fixed effects in our regression model (Bijnens et al., 2018). We provide a detailed description and measurement of each variable in Table 1.

| Variables | Abbreviation | Description | Sources | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | ||||

| Fee income | FeeInc | Income generated through non-banking activities including trading, a proxy of bank model. | Bank Scope | Beck et al. (2013) |

| Efficiency | SFA | Bank efficiency score measured through stochastic frontier analysis (SFA). | Authors' own calculation | Beck et al. (2013) |

| Z-Score | Z-Score | Measurement of the stability of the bank. | Authors' own calculation | Srairi (2019) |

| Non-performing loans | NPL | Non-performing loans as a percentage of gross loans, as a proxy of credit risk. | Bank Scope | İncekara and Çetinkaya (2019) |

| Independent | ||||

| Corruption | CIP | Perceived level of corruption provided by Transparency International. CI represents the original score under the Corruption Perception Index (TI Index) where a higher score suggests a higher economic and political integrity. | Transparency International | Bougatef (2015) |

| Controls | ||||

| Firm-level | ||||

| Firm size | Size | Natural logarithm of total asset, a proxy of firm size. | Bank Scope | Lassoued (2018) |

| Asset growth | AG | (Asset – Asset(t−1))/Asset(t−1) | Bank Scope | Srairi (2019) |

| Leverage | Leverage | Equity over total liabilities. | Bank Scope | Kabir et al. (2015) |

| Country-level | ||||

| GDP growth (%) | GDPG | Growth rate percentage of real GDP | World Bank | Lassoued (2018) |

| Inflation | INF | Inflation growth is measured using the annual percentage change in the consumer price index. | World Bank | Lassoued (2018) |

| Gross national income | GNI | Growth rate percentage of Gross National Income per capita based on Purchasing Power Parity. | World Bank | Dietz et al. (2007) |

| Country governance | Countrygov | Country-level governance scores published by World Bank which includes six measures of governance. We use the growth in the country-level governance score to reflect the annual change in the governance score. | World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators (WDI) | Chen et al. (2015) |

| Bank sector development | Bank Credit | Credit to private sector/GDP | World Bank | Srairi (2019) |

| Firm*Year | F*Y | This variable is introduced to test the widest possible set of fixed effect. | Authors' own calculation | Bijnens et al. (2018) |

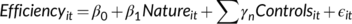

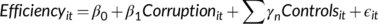

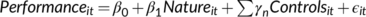

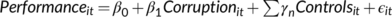

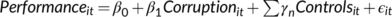

4.3 Model specification

(1)

(1) (2)

(2) (3)

(3) is the constant term. Islamic,

is the constant term. Islamic,  ,

,  , and

, and  are independent variable,

are independent variable,  represents both firm and country-level control variables, which include firm size, asset growth, leverage, capital asset ratio, GDP growth, inflation, country governance, and banking sector development. We also introduce the country*year variable to control any unobserved country-specific, time-invariant effects.

represents both firm and country-level control variables, which include firm size, asset growth, leverage, capital asset ratio, GDP growth, inflation, country governance, and banking sector development. We also introduce the country*year variable to control any unobserved country-specific, time-invariant effects.  represents error term. We provide a detailed description of the variables in Table 1. The preliminary estimation is estimated using a balanced panel of 77 banks operating in 6 GCC countries for 2005–2014.

represents error term. We provide a detailed description of the variables in Table 1. The preliminary estimation is estimated using a balanced panel of 77 banks operating in 6 GCC countries for 2005–2014.5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for our study. We have chosen fee-based income as a measure of business orientation following Beck et al. (2013). The mean for fee-based income for the full sample is 2.3%; the standard deviation is 0.018. Therefore, we find income generated by selected banks through providing services that are uniform across the sample. The average bank efficiency score is 80.10%, with a standard deviation of 0.148. The mean for the Z-score is 21.805, with a deviation of 16.74. A high z-score indicates more excellent stability for the banking sector, and we find that bank stability varies to a greater extent among the sample banks. The minimum (2.65) and maximum (89.19) values of the z-score indicate a balanced sample with banks having a high and low level of stability.

| Variable | Observations | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | |||||

| Fee income | 572 | 0.023 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.137 |

| Efficiency | 678 | 0.801 | 0.148 | 0.352 | 0.974 |

| Z-score | 704 | 21.805 | 16.743 | 2.652 | 89.194 |

| Non-performing loans | 280 | 1.464 | 0.576 | 0.077 | 2.439 |

| Independent | |||||

| Corruption | 770 | 4.495 | 1.053 | 2.300 | 6.700 |

| Controls | |||||

| Firm-level | |||||

| Size | 708 | 9.007 | 1.255 | 6.180 | 11.501 |

| Asset growth | 631 | 0.187 | 0.252 | −0.226 | 1.487 |

| Leverage | 708 | 6.198 | 2.641 | 0.180 | 14.322 |

| Country level | |||||

| GDP growth | 770 | 5.319 | 5.018 | −7.076 | 26.170 |

| Inflation | 621 | −0.146 | 1.518 | −7.870 | 3.609 |

| Country governance | 693 | −0.031 | 0.531 | −2.081 | 1.235 |

| Gross national income | 611 | −0.106 | 3.832 | −6.739 | 14.358 |

| Bank credit to GDP | 539 | 1.070 | 0.260 | 0.661 | 1.998 |

- Note: Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the variables in the study. We have introduced four proxies to measure bank efficiency, that is, fee income, efficiency and z-score. Bank orientation is measured with fee income, the efficiency of bank operation is measured through stochastic frontier analysis, z-score is a measure of earning volatility and non-performing loans measure the extent of credit risk for the selected banks. Corruption is the independent variable in this study. Adjusted Corruption Perception Index (CPI) scores are used in the main regression model Our regression model has both firm and country-level controls. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage. Country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and Bank credit to GDP. A brief explanation of the variables and their measurement is provided in Table 1.

Corruption scores, CPI, indicate a mean score of 4.50. The index is scored on a level of 0 (low corruption) to 10 (high corruption). The corruption score for GCC countries varies between countries with a higher standard deviation score of 1.05. We provide original corruption scores in Appendix A (Table A2). Qatar had the lowest corruption score (10 – Original CPI = 10–7.7 = 2.3) in 2010 while Saudi Arabia had the highest corruption score (6.7 adjusted) in the region in 2006. However, the level of corruption increased for Qatar in 2014, while Saudi Arabia was able to reduce its corruption level in the sample year. We find that only Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have a corruption level below the mean corruption score for the overall sample in the GCC region.

The average firm size is 9.00, with a deviation of 1.25. Asset growth has a mean score of 18.7%. Banks selected for this study have high leverage with a mean score of 6.20 and a standard deviation of 2.64. Turning to country-level variables, we find GDP growth ranges from −7.08 to 26.17 with a mean score of 5.02%. Inflation growth ranges between −7.87 and 3.61, with a mean score of 3.61. We find that Qatar had a negative inflation score of −4.86 in 2009. Such scores indicate the effort of the Government of Qatar to reduce the increasing inflation rate amid tension with several countries in the Arab region. The average gross national income growth is −10.6%, with a deviation of 3.832. Finally, bank credit to GDP has a mean score of 1.07%. The World Bank has established a threshold of bank credit to GDP ratio to 77%, and countries crossing the threshold can expect an economic slowdown. We find the highest (199.772%) bank credit to GDP ratio for Saudi Arabia and the lowest ratio (66.147%) for Qatar.

Bank efficiency (measured using SFA scores) and corruption have a negative correlation (Table 3). Such a score indicates that countries with a higher level of corruption may have a less efficient banking sector. We also find that the correlation between corruption and credit risk (NPL); corruption, and z-score (stability) are also harmful. The correlation between bank orientation and corruption is also negative. After conducting the unit root test, we find the data to be stationary at the level. We winsorise the data to limit the possibilities of extreme value before proceeding to regression analysis.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fee income | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 2 | Efficiency | −0.031 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Z-score | −0.123 | 0.105 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 4 | Non-performing loans | −0.061 | −0.032 | 0.044 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 5 | Corruption | −0.054 | −0.053 | −0.042 | −0.825 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 6 | Size | −0.138 | 0.051 | −0.077 | −0.344 | 0.341 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 7 | Asset growth | −0.079 | −0.179 | 0.078 | −0.055 | −0.010 | −0.123 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 8 | Debt-equity ratio | −0.129 | −0.218 | −0.388 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.419 | 0.138 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 9 | GDP growth | −0.129 | −0.218 | −0.388 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.419 | 0.138 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 10 | Inflation | −0.012 | 0.093 | 0.032 | 0.029 | 0.036 | 0.069 | 0.001 | −0.089 | −0.089 | 1.000 | ||||

| 11 | Country governance | −0.105 | 0.226 | 0.078 | 0.162 | −0.223 | 0.027 | 0.028 | −0.088 | −0.088 | 0.558 | 1.000 | |||

| 12 | Gross national income | 0.043 | 0.108 | 0.071 | −0.021 | −0.132 | −0.021 | −0.029 | −0.020 | −0.020 | 0.078 | 0.200 | 1.000 | ||

| 13 | Bank credit to GDP | 0.016 | 0.026 | 0.011 | 0.249 | −0.233 | −0.084 | −0.158 | −0.062 | −0.062 | 0.604 | 0.283 | 0.274 | 1.000 | |

| 14 | Fee income | 0.103 | −0.052 | 0.029 | −0.607 | 0.678 | 0.226 | −0.076 | −0.059 | −0.059 | −0.193 | −0.356 | 0.031 | −0.215 | 1.000 |

- Note: We have conducted a Pearson correlation analysis. We do not find a high correlation among the variables. Therefore, this study is not affected by multicollinearity issues.

5.2 Regression analysis

5.2.1 Bank efficiency in GCC: Comparison between conventional and Islamic banks

We begin our regression analysis with that comparative note and explore the differences in the efficiency between conventional and Islamic banks. Such a comparison has already been conducted in past studies for a wide variety of samples (Al-Kayed, 2017; Beck et al., 2013; Sharmeen et al., 2019). We introduce a dummy variable in the regression model, as described in Section 4.3. We use a dummy variable, a value of 1 is assigned for Islamic banks and 0 otherwise. Table 4 provides results from the regression analysis. We run the regression for bank efficiency, measured using four proxies as described in Table 1. We report a statistically significant difference in efficiency and z-score, which is not substantial for fee income. We report Islamic banks are lacking in terms of cost efficiency and stability (Kamarudin et al., 2013, 2014; Sufian & Kamarudin, 2014b). Beck et al. (2013) conclude that Islamic banks are likely to charge higher fees, and our results confirm such findings for the GCC region. Similar to the findings of Miah and Uddin (2017), we also ensure that Islamic banks are less efficient than conventional banks. Our results are in line with Zeineb and Mensi (2018), as we also find that Islamic banks in the GCC region are less stable than their conventional counterparts. Such findings allow us to conduct further analysis of the possible reason for such a difference in business orientation, efficiency, stability, and similarities in credit risk for the sample.

| Fee income | Efficiency | Z-score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Islamic | 0.000 | −0.187*** | −6.947*** |

| −0.080 | (−14.53) | (−4.12) | |

| Size | −0.001 | 0.014* | 0.314 |

| (−1.27) | −2.250 | −0.510 | |

| Asset growth | 0.006 | 0.038 | 7.398 |

| −0.770 | −1.190 | −1.700 | |

| Leverage | −0.001** | −0.007** | −1.531*** |

| (−3.18) | (−2.70) | (−4.50) | |

| GDP growth | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.227 |

| −0.310 | −0.010 | −1.140 | |

| Inflation | 0.001 | 0.008 | −0.545 |

| −1.210 | −1.740 | (−0.93) | |

| Country governance | 0.001 | 0.012 | −0.085 |

| −0.740 | −1.090 | (−0.05) | |

| Gross national income | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.114 |

| (−0.12) | −0.150 | (−0.51) | |

| Bank credit to GDP | 0.006*** | −0.002 | −7.002** |

| −3.750 | (−0.15) | (−3.04) | |

| Firm*Year | 0.000 | −0.000* | 0.000 |

| (−0.85) | (−2.39) | (−0.36) | |

| Constant | 0.028*** | 0.819*** | 36.372*** |

| −3.420 | −13.150 | −5.490 | |

| Observations | 363 | 449 | 467 |

| Mean VIF | 1.300 | 1.210 | 1.230 |

| F(10, 352) | 3.030** | 30.330*** | 7.930*** |

| R-squared | 0.095 | 0.415 | 0.111 |

-

Note: We perform regression based on the model:

. Efficiency is the dependent variable in the regression model and we have used three proxies to measure the efficiency of selected banks. These proxies include fee income (model 1), efficiency (model 2) and z-score (model 3). Islamic, the independent variable in the model, is a dummy variable. A score of 1 is given for Islamic banks and 0 for conventional banks. The introduction of such a dummy variable in the regression model allows us to explore the difference in the efficiency between Islamic and conventional banks in the GCC region, in the presence of all control variables. We have used both firm and country-level controls in this model. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and Bank credit to GDP. We provide both standardised coefficient score along with their robust t-value (in the parenthesis). ***, ** and * and indicate the significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

. Efficiency is the dependent variable in the regression model and we have used three proxies to measure the efficiency of selected banks. These proxies include fee income (model 1), efficiency (model 2) and z-score (model 3). Islamic, the independent variable in the model, is a dummy variable. A score of 1 is given for Islamic banks and 0 for conventional banks. The introduction of such a dummy variable in the regression model allows us to explore the difference in the efficiency between Islamic and conventional banks in the GCC region, in the presence of all control variables. We have used both firm and country-level controls in this model. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and Bank credit to GDP. We provide both standardised coefficient score along with their robust t-value (in the parenthesis). ***, ** and * and indicate the significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

Empirical evidence on the extent of banking sector efficiency is available. While past studies (Mostafa, 2007) indicate that there is room for improvement in terms of the performance banks in the GCC region, the causes of such sub-par performance have seldom been explored. Hence, in the next level of analysis, we introduce our primary independent variable, corruption. Studies conducted by Kamarudin et al. (2016) and Zeineb and Mensi (2018) are different in this regard as they explore the importance of stable governance for a stable and efficient baking sector in the GCC region. The impact of corruption on the soundness of Islamic banks is explored for the first time by Bougatef (2015). While our study is influenced by the findings of Bougatef (2015), there is a clear distinction between the two studies in three areas. First, the sample is different. Bougatef (2015) focused on only Islamic banks operating in 16 countries, five countries from the GCC region, excluding Oman. We cover banks operating in six GCC countries, which allow us to provide a comparative analysis. Second, Bougatef (2015) only focuses on delivering empirical analysis and does not justify the findings with any theoretical background due to its exploratory nature. In the current study, we explain the nexus between corruption and bank efficiency with the ‘grease or sand-the-wheel’ hypothesis. Finally, unlike Bougatef (2015), which only focuses on non-performing finance, we provide a more comprehensive look at bank efficiency by introducing four proxies of bank efficiency. Therefore, we continue to our next level of analysis by replacing the Islamic dummy with corruption.

5.2.2 Corruption and bank efficiency

Table 5 provides both OLS and GMM regression results for Equation (2). We use the full sample of 77 banks to conduct the regression analysis. Equation (2) explores the overall effect of corruption on GCC banks before proceeding toward the comparative analysis. We find corruption to have a significant negative impact on the efficiency of GCC banks. The effect of corruption on the fee income and stability of the selected banks is not significant. Table 5 provides an r-square of 8.7% for the regression model with efficiency measured using SFA. Therefore, we conclude that bank efficiency in the GCC region decreases with the increase in corruption.

| Fee income | Efficiency | Z-score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | GMM | OLS | GMM | OLS | GMM | |

| Dependent variable t−1 | 0.148 | 0.956*** | 0.546*** | |||

| −1.210 | −84.020 | −4.320 | ||||

| Corruption | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.019* | 0.000 | −0.013 | 0.274 |

| −0.100 | −1.310 | (−2.27) | −1.160 | (−0.01) | −0.460 | |

| Size | −0.001 | −0.005 | 0.023** | −0.001 | 0.699 | −0.484 |

| (−1.29) | (−1.15) | −3.230 | (−1.06) | −1.100 | (−0.24) | |

| Asset growth | 0.006 | 0.004 | −0.056 | −0.001 | 4.788 | −5.476* |

| −0.780 | −1.280 | (−1.55) | (−1.54) | −1.160 | (−2.58) | |

| Leverage | −0.001** | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.000 | −1.433*** | −1.987*** |

| (−3.11) | (−0.09) | (−0.78) | −1.860 | (−4.15) | (−7.93) | |

| GDP growth | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.271 | 0.217*** |

| −0.300 | −0.710 | −1.060 | (−0.57) | −1.340 | −4.630 | |

| Inflation | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.000 | −0.461 | 0.062 |

| −1.160 | −0.700 | −1.560 | (−0.32) | (−0.74) | −0.730 | |

| Country governance | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.105 | 0.015 |

| −0.720 | −0.530 | −0.860 | (−0.35) | −0.060 | −0.070 | |

| Gross national income | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.000 | −0.160 | −0.130*** |

| (−0.10) | (−0.16) | (−1.03) | (−0.66) | (−0.74) | (−3.65) | |

| Bank credit to GDP | 0.006 | −0.003 | 0.056 | 0.001 | −6.747 | 8.224** |

| −1.930 | (−0.52) | −1.900 | −1.340 | (−1.57) | −3.000 | |

| Constant | 0.028*** | 0.738 | 0.653*** | 0.284 | 29.175*** | −743.666* |

| −3.750 | −0.880 | −9.930 | −1.170 | −4.210 | (−1.99) | |

| Observations | 363 | 284 | 449 | 367 | 467 | 389 |

| Firm*Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F/Wald statistics | 3.200*** | 45.510*** | 2.980** | 104*** | 4.860 | 157.430*** |

| R-squared | 0.095 | 0.087 | 0.076 | |||

| Mean VIF | 1.460 | 1.350 | 1.370 | |||

-

Note: We perform OLS and GMM regression based on the following models:

Efficiency and

Efficiency and  Efficiency is the dependent variable in the regression model, and we have used three proxies to measure the efficiency of selected banks. These proxies include fee income (model 1), efficiency (model 2) and z-score (model 3). Corruption, the independent variable in the model, is measured using the adjusted Corruption Perception Index (CPI) score. We have used both firm and country-level controls in this model. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage. Country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income and inflation. Country-level controls include GDP growth, gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and bank credit to GDP. We provide both standardised coefficient score along with their robust t-value (in the parentheses) for the full sample in this table. ***, ** and * and indicate the significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

Efficiency is the dependent variable in the regression model, and we have used three proxies to measure the efficiency of selected banks. These proxies include fee income (model 1), efficiency (model 2) and z-score (model 3). Corruption, the independent variable in the model, is measured using the adjusted Corruption Perception Index (CPI) score. We have used both firm and country-level controls in this model. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage. Country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income and inflation. Country-level controls include GDP growth, gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and bank credit to GDP. We provide both standardised coefficient score along with their robust t-value (in the parentheses) for the full sample in this table. ***, ** and * and indicate the significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

Consequently, we find evidence to support the ‘sand the wheel’ hypothesis. Our results are in line with the findings of Bougatef (2017) and Dreher and Gassebner (2013) and contradict the findings of Cooray and Schneider (2018). We confirm that the highly regulated banking sector in the GCC region is providing enough mechanisms to cope with the negative influence of corruption on the GCC banks. Among firm-level controls, size and leverage have a significant negative impact on various measures of bank efficiency. We find GDP growth and bank capital to GDP positively affect credit risk, while Bank credit to GDP positively impacts bank efficiency in GCC.

5.2.3 Sub-sample analysis

We conduct further analysis to explore differences in the impact of corruption on bank efficiency. As such, we repeat the regression using equation two by dividing the banks into Islamic and conventional. Table 6 exhibits regression results for Islamic banks. We find that corruption has a diverse impact on the efficiency of different types of banks in the GCC region. We find in Table 6 that corruption increases the fee income for Islamic banks. However, the impact of corruption on the sustainability of Islamic banks is negative and significant. Corruption does not affect the efficiency of Islamic banks in the GCC region. Park (2012) provides one of the early pieces of evidence of a negative relationship between corruption and the soundness of banking sector operations. He further concludes that corruption affects the optimal allocation of loanable funds. Our results confirm the findings of Park (2012), and we conclude that the sustainability of Islamic banks in the GCC region is affected by the increase of corruption. Therefore, we confirm the ‘sand the wheel’ hypothesis for Islamic banks.

| Fee income | Efficiency | Z-score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islamic | Conventional | Islamic | Conventional | Islamic | Conventional | |

| Corruption | 0.005* | −0.001 | −0.015 | −0.002 | −4.539* | 2.480* |

| −1.930 | (−1.64) | (−1.09) | (−0.24) | (−1.81) | −2.180 | |

| Size | −0.003 | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.923 | 0.249 |

| (−1.83) | (−0.60) | −1.310 | −1.200 | −0.800 | −0.370 | |

| Asset growth | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.030 | 13.202 | −2.092 |

| −0.970 | −0.030 | −0.230 | −1.430 | −1.800 | (−0.50) | |

| Debt-equity ratio | 0.000 | −0.001** | −0.013* | 0.001 | −2.591*** | −1.508*** |

| (−0.10) | (−3.29) | (−2.07) | −0.270 | (−4.55) | (−3.70) | |

| GDP growth | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | −0.002* | −0.790 | 0.652*** |

| −0.870 | (−0.15) | −1.170 | (−2.30) | (−1.52) | −3.800 | |

| Inflation | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.282 | −1.137 |

| −1.370 | (−0.26) | −1.580 | −0.690 | −0.390 | (−1.37) | |

| Country governance | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 2.690 | −1.902 |

| −0.850 | −0.060 | −0.830 | −0.690 | −0.990 | (−0.89) | |

| Gross national income | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.670 | −0.357* |

| −0.300 | (−0.56) | (−0.50) | −1.080 | −1.190 | (−2.25) | |

| Bank credit to GDP | 0.001 | 0.009*** | 0.107* | −0.032 | −4.898 | −15.703*** |

| −0.090 | −3.640 | −2.130 | (−1.18) | (−0.67) | (−3.42) | |

| Firm*Year | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000** | −0.000* | 0.000 |

| −0.920 | (−0.85) | −0.010 | (−2.85) | (−2.55) | −1.800 | |

| Constant | 0.023 | 0.027*** | 0.550** | 0.880*** | 59.496*** | 30.770*** |

| −0.930 | −4.710 | −3.160 | −14.070 | −3.460 | −4.840 | |

| Observations | 118 | 245 | 148 | 301 | 155 | 312 |

| F(10, 107) | 2.150** | 5.250*** | 3.810*** | 2.600*** | 4.210*** | 6.820*** |

| R-squared | 0.134 | 0.141 | 0.151 | 0.060 | 0.213 | 0.173 |

-

Note: We perform regression based on the following model:

. Efficiency is the dependent variable in the regression model, and we have used three proxies to measure the efficiency of selected banks. We divide the full sample according to Islamic and conventional banks to provide a comparative analysis of the impact of corruption on the performance of various types of banks. These proxies include fee income (model 1), efficiency (model 2) and z-score (model 3). Corruption, the independent variable in the model, is measured using the adjusted Corruption Perception Index (CPI) score provided by Transparency International. We have used both firm and country-level controls in this model. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage. Country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income and inflation. Country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and Bank credit to GDP. We provide both standardised coefficient score along with their robust t-value (in the parentheses) for the full sample in this table. ***, ** and * and indicate the significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

. Efficiency is the dependent variable in the regression model, and we have used three proxies to measure the efficiency of selected banks. We divide the full sample according to Islamic and conventional banks to provide a comparative analysis of the impact of corruption on the performance of various types of banks. These proxies include fee income (model 1), efficiency (model 2) and z-score (model 3). Corruption, the independent variable in the model, is measured using the adjusted Corruption Perception Index (CPI) score provided by Transparency International. We have used both firm and country-level controls in this model. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage. Country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income and inflation. Country-level controls include GDP growth, Gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and Bank credit to GDP. We provide both standardised coefficient score along with their robust t-value (in the parentheses) for the full sample in this table. ***, ** and * and indicate the significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

However, we do not find a similar impact of corruption on conventional bank performance. In Table 6, we find a positive impact of corruption on the stability of conventional Banks in the GCC region. Corruption does not have a significant relationship with bank orientation and the efficiency of conventional banks. Such results allow us to confirm that in the GCC region, bank efficiency and stability for Islamic and conventional banks increases with the level of corruption. As a result, we confirm the ‘grease the wheel’ hypothesis for conventional banks in the GCC region and conclude that the increase in corruption can enhance the stability of conventional banks in the GCC region. Our study contradicts the findings of Park (2012) for the banking sector in the GCC region. Gambling and Karim (1986) confirm that Islamic banks might differ from conventional banks due to the inherent mechanisms in the Islamic framework. We complement the findings of Li and Wu (2010) by confirming that corruption can become an efficiency-enhancing contributor to conventional banks and, at the same time, complement the results of Bougatef (2017) concerning Islamic banks operating in the GCC region. In the absence of institutional infrastructures in combating corruption, we find that Islamic banks have utilised internal mechanisms such as Equidae (Jabbar, 2011) to tackle the negative impact of corruption on their efficiency.

5.2.4 Robustness analysis

We conduct a robustness analysis of our regression model in several stages. First, we introduce an interaction variable, Corruption*Islamic, to further establish the moderating influence of the nature of the bank in the corruption and bank efficiency relationship. Table 7 provides the results of such moderation analysis. We find the interaction is significant and negative for bank efficiency and sustainability (measured with z-score). Such impact is insignificant between the interaction variable and bank orientation (measured by fee income). In all regression models, the original corruption variable turns insignificant after the introduction of the interaction variable. Therefore, we prove that the nature of banks moderates the impact of corruption on bank efficiency. For Islamic banks in the GCC, the increase of corruption reduces efficiency and sustainability. Such results allow us to confirm the ‘sand the wheel’ hypothesis for Islamic banks in the GCC region.

| Fee income | Efficiency | Z-score | Non-performing loans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.940 | −0.344*** | −0.353*** | ||

| −0.030 | −1.160 | −0.840 | (−10.61) | (−10.04) | |||

| Control of corruption | 0.131*** | 0.132*** | |||||

| −6.340 | −5.960 | ||||||

| Corr*Islamic | 0.000 | −0.041*** | −1.773*** | 0.009 | −0.001 | ||

| −0.460 | (−13.64) | (−4.50) | −0.630 | (−0.05) | |||

| Size | −0.001 | 0.014* | 0.353 | −0.106*** | −0.149*** | −0.101*** | −0.149*** |

| (−1.24) | −2.290 | −0.570 | (−3.87) | (−5.16) | (−3.60) | (−5.16) | |

| Asset growth | 0.006 | 0.023 | 7.285 | −0.263* | −0.458** | −0.286* | −0.459** |

| −0.740 | −0.760 | −1.680 | (−2.40) | (−2.71) | (−2.45) | (−2.65) | |

| Debt-equity ratio | −0.001** | −0.009** | −1.628*** | 0.022* | 0.028* | 0.022* | 0.028* |

| (−3.09) | (−3.19) | (−4.90) | −2.120 | −2.470 | −2.000 | −2.430 | |

| GDP growth | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.213 | 0.010 | 0.055** | 0.010 | 0.055** |

| −0.310 | (−0.28) | −1.070 | −1.140 | −3.130 | −1.190 | −3.130 | |

| Inflation | 0.001 | 0.008 | −0.511 | −0.032 | −0.082 | −0.034 | −0.082 |

| −1.170 | −1.780 | (−0.86) | (−0.69) | (−1.17) | (−0.74) | (−1.16) | |

| Country governance | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.037 | −0.087 | 0.005 | −0.087 | 0.005 |

| −0.730 | −1.080 | −0.020 | (−1.32) | −0.070 | (−1.33) | −0.080 | |

| Gross national income | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.093 | 0.002 | −0.015 | 0.002 | −0.015 |

| (−0.11) | −0.040 | (−0.42) | −0.500 | (−1.81) | −0.420 | (−1.81) | |

| Bank credit to GDP | 0.006 | 0.011 | −8.058 | −0.178 | −0.735*** | −0.170 | −0.735*** |

| −1.900 | −0.430 | (−1.87) | (−1.07) | (−5.64) | (−1.01) | (−5.63) | |

| 0.000 | −0.000*** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| (−0.76) | (−3.51) | (−0.68) | −0.300 | (−0.33) | −0.580 | (−0.31) | |

| Constant | 0.027*** | 0.794*** | 34.551*** | 3.876*** | 3.491*** | 3.841*** | 3.490*** |

| −3.770 | −13.130 | −4.960 | −16.890 | −13.170 | −16.790 | −13.170 | |

| Observations | 363 | 449 | 467 | 238 | 238 | 238 | 238 |

| Firm*Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F(11, 351) | 2.910 | 25.520 | 7.410 | 82.650 | 35.200 | 75.190 | 31.870 |

| R-squared | 0.095 | 0.400 | 0.120 | 0.655 | 0.558 | 0.655 | 0.558 |

-

Note: We perform robust regression based on the following model:

:. Efficiency is the dependent variable in the regression model and we have used four proxies to measure the efficiency of selected banks. These proxies include fee income (model 1), efficiency (model 2) and z-score (model 3). In addition to the three exiting proxies of efficiency, we include additional proxy in the regression model which is non-performing loans (NPL) (model 4). Corruption is measured using the adjusted Corruption Perception Index (CPI) score provided by Transparency International. We introduce an interaction variable, Corruption*Islamic, in the regression model to explore possible moderation of the nature of the bank between corruption and bank efficiency. We also introduce additional corruption measure, control of corruption from the World Governance Indicators database, in model 5 to ensure the robustness of the analysis. We have used both firm and country-level controls in this model. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage and capital asset ratio. Country-level controls include GDP growth, gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and Bank credit to GDP. We provide both standardised coefficient score along with their robust t-value (in the parentheses) for the full sample in this table. ***, ** and * and indicate the significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

:. Efficiency is the dependent variable in the regression model and we have used four proxies to measure the efficiency of selected banks. These proxies include fee income (model 1), efficiency (model 2) and z-score (model 3). In addition to the three exiting proxies of efficiency, we include additional proxy in the regression model which is non-performing loans (NPL) (model 4). Corruption is measured using the adjusted Corruption Perception Index (CPI) score provided by Transparency International. We introduce an interaction variable, Corruption*Islamic, in the regression model to explore possible moderation of the nature of the bank between corruption and bank efficiency. We also introduce additional corruption measure, control of corruption from the World Governance Indicators database, in model 5 to ensure the robustness of the analysis. We have used both firm and country-level controls in this model. Firm-level controls include firm size, asset growth and leverage and capital asset ratio. Country-level controls include GDP growth, gross national income, inflation, country-level governance and Bank credit to GDP. We provide both standardised coefficient score along with their robust t-value (in the parentheses) for the full sample in this table. ***, ** and * and indicate the significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

In the second stage, we introduce credit risk as the dependent variable. Credit risk is proxied by non-performing loans as a percentage of gross loans. We run regression between credit risk and the adjusted CPI scores and find that a higher level of corruption results in the reduction of credit risk. Finally, we introduce a new measure of corruption, control of corruption, from the World Governance Indicators. The control of corruption score ranges between-2.5 to 2.5, and a lower score indicates the perception of a higher level of corruption. Using the new corruption measure, we find that the increase in corruption reduces the level of credit risk for banks in the GCC region. The mediating influence is insignificant for credit risk. We explain the negative relationship between corruption and credit risk by highlighting the findings of Mokhtar and Zakaria (2009). Mokhtar and Zakaria (2009) report that Islamic banks are efficient in managing non-performing loans than conventional banks. In the context of emerging economies, the nexus between corruption and development has not been straightforward. Emerging markets have experienced superior economic growth with the existence of high corruption (Chen et al., 2015). In the GCC region, we find that a high level of corruption boosts the efficiency of the banking sector by allowing credit to the most significant and efficient producers who, in turn, ensures efficient management and allocation of loans.

6 DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study is to explore the impact of corruption on bank efficiency. We explore the ‘Sand or Grese the wheel’ hypothesis in the context of the GCC region. Recently, Cooray and Schneider (2018) report that corruption sand the development of the financial sector. Yakubu (2019) confirms the validity of the findings of Cooray and Schneider (2018) for Ghana. Hasan and Ashfaq (2021), however, indicate that the relationship between corruption and bank efficiency is not straightforward and might change based on the nature of the business model. While Mouselli et al. (2016) provide evidence on a positive association between corruption and stock market development in the GCC region, we have limited evidence on the possible impact of corruption on the GCC banking sector. Considering the higher corruption score among the GCC countries, mixed impact of corruption on economic and financial sector development and positive impact of corruption on the stock market development reported by Mouselli et al. (2016) for the GCC sector, we expect our study findings could provide vital information for the regulators and banking industry practitioners.

We begin our analysis with a comparative overview of the efficiency between conventional and Islamic banks in the GCC region. We report that conventional banks and cost-efficient and stable as compared to Islamic banks. Such findings are consistent with Miah and Uddin (2017) and Zeineb and Mensi (2018) and we proceed with hypothesis testing to investigate whether corruption has any impact on the efficiency of conventional and Islamic banks in the GCC region.

We begin our investigation with the full sample and find that corruption sand the efficiency of the banking sector in the GCC region. Our results support the findings of Cooray and Schneider (2018) and Yakubu (2019); confirming the appropriateness of the ‘Sand or Grese the wheel’ hypothesis toward exploring bank efficiency. We continue our investigation with a sub-sample analysis and report a diverse impact of corruption between conventional and Islamic banks. While we report a negative association between corruption and the efficiency of Islamic banks, such a relationship is positive for conventional banks. Such findings complement the findings of Li and Wu (2010) and indicate the complexity of the corruption problem that might require dynamic regulatory measures in the GCC region to protect the development of the financial sector.

7 CONCLUDING REMARKS

Ordinary people suffer in corrupt societies as they fail to stand up for their rights and demonstrate concern when the basic needs are not met. Corruption has been a prominent research agenda in the last decade as its impact on various economic factors for various parts of the world, and the result is inconclusive. Arab countries traditionally do not perform well in the CPI ranking produced by Transparency International. However, the GCC region has seen exponential growth in the banking sector, especially the Islamic finance industry. Hence, this study focused on exploring the impact of corruption on the efficiency of the banking sector to provide generalisable evidence that reduces the gap in the literature.

We conduct regression analyses on 77 banks' operations in six GCC countries. At the initial stage, we establish a statistically significant difference between the efficiency of Islamic and conventional banks. Islamic banks have higher income from non-banking operations. However, in terms of cost-efficiency, conventional banks perform better than Islamic banks. Further analysis reveals the negative impact of corruption on the efficiency of the overall banking sector in the GCC region. We conduct additional analysis to conclude that corruption has a ‘grease the wheel’ effect for Islamic banks and a ‘sand the wheel’ effect on the efficiency of conventional banks.

Our study makes a significant contribution to the literature in two ways. First, we provide statistical evidence that corruption is detrimental to the efficiency of the banking sector in GCC countries. However, the impact of corruption is not the same for all types of banks, and the impact varies with the type of efficiency indicator used in the analysis. Such findings indicate a lack of uniform institutional and governance framework in the GCC region, which might have allowed Islamic banks to deviate from their theoretical model and compete fiercely for increasing market share. Such a multidimensional impact of corruption on the efficiency of banks is the second contribution of this study to the literature as we have demonstrated that corruption acts as a grease for efficiency among Islamic banks in the GCC region. We, therefore, conclude that all aspect of governance, both traditional and Shari'ah, takes a central role to mitigate the impact of corruption on bank efficiency. Future studies could explore the role of Shari'ah supervision as a risk management tool for the global Islamic banking sector.

8 PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The regulatory authority in the GCC region could benefit from our empirical findings and we expect our findings will lead to the development of holistic governance for both conventional and Islamic banks in this region with the central focus to reduce the detrimental impact of corruption in the banking sector development. Thus, our study brings a new challenge for the policymaker as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ view toward combating corruption may not result in an efficient solution for all parts of the world. Our findings have further implications for the GCC banking sector as we report that corruption affects conventional and Islamic banks differently in this region. As such, each bank could benefit by reviewing their risk management policy to ensure they implement appropriate mechanisms to mitigate risk arising for firm-level and country-level corruption.

Appendix A

| Year | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Observations | ||

| Country | Bank type | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 170 |

| Bahrain | ||||||||||||

| Conventional | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 90 | |

| Islamic | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 80 | |

| Kuwait | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 80 | |

| Conventional | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 30 | |

| Islamic | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 50 | |

| Oman | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 60 | |

| Conventional | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 60 | |

| Qatar | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 100 | |

| Conventional | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 60 | |

| Islamic | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 40 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 120 | |

| Conventional | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 80 | |

| Islamic | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 40 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 240 | |

| Conventional | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 170 | |

| Islamic | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 70 | |

| Grand Total | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 770 | |

| Country | Bahrain | Kuwait | Oman | Qatar | Saudi Arabia | United Arab Emirates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Corruption ranking | CIP score | Corruption ranking | CIP score | Corruption ranking | CIP score | Corruption ranking | CIP score | Corruption ranking | CIP score | Corruption ranking | CIP score |

| 2005 | 36 | 5.8 | 45 | 4.7 | 28 | 6.3 | 32 | 5.9 | 70 | 3.4 | 30 | 6.2 |

| 2006 | 36 | 5.7 | 46 | 4.8 | 39 | 5.4 | 32 | 6.0 | 70 | 3.3 | 31 | 6.2 |

| 2007 | 46 | 5.0 | 65 | 4.3 | 53 | 4.7 | 32 | 6.0 | 79 | 3.4 | 34 | 5.4 |

| 2008 | 43 | 5.4 | 65 | 4.3 | 41 | 5.5 | 28 | 6.5 | 80 | 3.5 | 35 | 5.9 |

| 2009 | 46 | 5.1 | 66 | 4.1 | 39 | 5.5 | 22 | 7.0 | 63 | 4.3 | 30 | 6.5 |

| 2010 | 48 | 4.9 | 54 | 4.5 | 41 | 5.3 | 19 | 7.7 | 50 | 4.7 | 28 | 6.3 |

| 2011 | 46 | 5.1 | 54 | 4.6 | 50 | 4.8 | 22 | 7.2 | 57 | 4.4 | 28 | 6.8 |

| 2012 | 53 | 5.1 | 66 | 4.4 | 61 | 4.7 | 27 | 6.8 | 66 | 4.4 | 27 | 6.8 |

| 2013 | 57 | 4.8 | 69 | 4.3 | 61 | 4.7 | 28 | 6.8 | 63 | 4.6 | 26 | 6.9 |

| 2014 | 55 | 4.9 | 67 | 4.4 | 64 | 4.5 | 27 | 6.9 | 55 | 4.9 | 26 | 7.0 |

Biographies

Dr. M. Kabir Hassan is a financial economist with consulting, research and teaching experiences in development finance, money and capital markets, Islamic finance, corporate finance, investments, monetary economics, macroeconomics and international trade and finance. He provided consulting services to the World Bank (WB), International Monetary Fund (IMF), Islamic Development Bank (IDB), African Development Bank (AfDB), USAID, Government of Bangladesh, Organization of Islamic Conferences (OIC), Federal Reserve Bank, USA, and many corporations, private organizations and universities around the world. Dr. Hassan received his BA in Economics and Mathematics from Gustavus Adolphus College, Minnesota, USA, and M.A. in Economics and Ph.D. in Finance from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA respectively. He is now a tenured Full Professor in the Department of Economics and Finance at the University of New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

Dr Rashedul Hasan is a Lecturer in Accounting at Coventry University, United Kingdom. Rashedul completed his PhD in 2018, which focuses on Corporate Governance issues for a non-profit organization. He is also a CIMA member and holds the designation of ACMA, CGMA. His research interest includes corporate governance dynamics, performance, and risk management aspects of financial institutions, sustainability, and accountability issues. Rashedul is serving as the Associate Editor of the Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development. He has been publishing his research in ABS, ABDC, and SCOPUS indexed accounting and finance journals.

Dr. Mohammad Dulal Miah is an Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Economics and Finance at the University of Nizwa, Oman. He has obtained his master's degree (MBA) in Finance and PhD in Development Economics from Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Japan. Dr. Miah has coauthored three academic books and contributed more than 30 research papers to peer reviewed journals. He has attended numerous international conferences as invited speaker and facilitator in various countries. Dr. Miah's research interest includes institutional economics, corporate governance, Islamic finance and banking, comparative financial systems, and environmental finance.

Dr Muhammad Ashfaq is working as Professor of Finance and Accounting at IU International University of Applied Sciences in Germany. He is also the Programme Director of Digital Business. He earned doctor of philosophy on the topic: “Knowledge, Attitude and Practices toward Islamic Banking and Finance: An Empirical Analysis of Retail Consumers in Germany” from the Tübingen University. Prof. Ashfaq holds an MBA in Financial Management from Coburg University. He is regular senior visiting faculty member at Wittenborg University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands and the international MBA program at Coburg University. His research interests include Islamic Finance and FinTech.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.