Interest group representation and framing in the media: A policy area perspective

Abstract

This article analyzes interest group representation and framing in the news media. In contrast to previous work, it focuses on the role of the policy area in shaping the types of groups appearing in the media and the frames used by groups. Empirically, the analysis maps group representation and framing across six different policy areas in the Danish news media. It distinguishes between whether groups frame their viewpoints as furthering (a) the interests of group members, (b) the interests of other specific societal groups, (c) broad economic concerns, or (d) public interests in general. Interest group representation and framing is found to vary between these policy areas. Some areas mainly contrast economic groups and the interests of their members, whereas debates in other areas are more likely to be shaped by references to beneficiaries of welfare state services or broad, public interests.

1 INTRODUCTION

A key characteristic of democracy is that different viewpoints are heard in public debates. This facilitates the representation of citizens and allows decision makers to be informed of a variety of perspectives (Dahl, 1998). Organized interests serve as transmission belts for citizen views into public debates and the political system. In effect, much attention has focused on the diversity in the range of voices represented by interest groups (Binderkrantz, Chaqués-Bonafont, & Halpin, 2017; Schattschneider, 1975; Schlozman, Verba, & Brady, 2012; Thrall, 2006). More recently, scholars have pointed to the importance of the way groups frame their arguments in public debates—do they emphasize the interests of their own membership or try to legitimate their views by highlighting broader societal concerns (Binderkrantz, 2019; Boräng & Naurin, 2015; Klüver, Mahoney, & Opper, 2015)?

Western democracies have become increasingly mediatized, and today, the news media is a crucial arena to access for organized interests (Strömbäck & Esser, 2014). Appearing in the news media comes with the added benefit of signaling to members that a group is actively lobbying on their behalf (Berkhout, 2013). Political communication is, however, not only about being present but also about expressing viewpoints in a manner that help groups achieve their goals. The importance of arguments was acknowledged already by Schattschneider (1975 [1969], p. 27) with his emphasis that “A public discussion must be carried on in public terms.” Later scholars have also argued that framing group concerns as furthering the public good may be a desired strategy for many interest groups (Ihlen et al., 2018; Rommetvedt, 2005).

This paper analyzes interest group representation and framing in the news media. In contrast to previous research, the analysis centers on the importance of the policy context for group appearances and frame use. The insight that group mobilization depends largely on the policy area in question is classic (Lowi, 1964; Wilson, 1980). Yet, as argued by Grossman, “many theories of the policy process largely sidestep the question of differences across issue areas and are meant to apply to many domains” (Grossmann, 2013, p. 66). In the interest group field, this is reflected in the number of studies focusing on aggregate patterns of interest group representation and communication (Binderkrantz, Christiansen, & Pedersen, 2015; Binderkrantz & Pedersen, 2019; Boräng & Naurin, 2015; Thrall, 2006).

The premise of this paper is that policy areas differ not only in the types of interests likely to be mobilized and gain media representation (Lowi, 1964; Wilson, 1980) but also in the prevalence of different frames. Some policy areas contrast the interests of organized groups such as labor and business, and debates are likely to center on these contrasts. Other policies —such as welfare state production—are mainly about helping specific societal groups, and the concerns of these groups may therefore dominate debates. Yet other areas invoke broader concerns such as climate change or human rights. To test the expected differences in interest group framing across policy areas, the paper distinguishes between whether groups frame their viewpoints as furthering (a) the interests of group members, (b) the interests of other specific societal groups, (c) broad economic concerns, or (d) public interests in general.

Empirically, the paper focuses on interest groups in Denmark. It draws on a content analysis of interest group presence and framing in two Danish newspapers. Group appearances were registered in two national newspapers, and for each appearance, the dominant frame used by the interest group was registered. To study the role of the policy area, six specific policy areas are analyzed: labor market policy, business and consumer policy, environment and energy policy, education policy, health policy, and justice and rights policy.

1.1 Media appearance and frames: Concepts and the role of the policy area

Framing concerns defining a problem in a particular way and linking this problem definition to relevant solutions. When interest groups frame their messages, they simultaneously highlight some features of a reality and downplay others. Frames can therefore be seen as strategic weapons that may help generate support for the preferred policy alternative of a group (Boräng & Naurin, 2015; Bruycker, 2016). Several studies point to the effect of frames in affecting group success, public opinion, and ultimately leading to policy change (Baumgartner, De Boef, & Boydstun, 2008; Dan & Rakness, Forthcoming; Dür, 2018; Junk & Rasmussen, 2018).To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described. (Entman, 1993, p. 52)

Although most framing studies use Entman's definition, there is much variation in the nature of the frames studied. Some focus on issue-specific frames where all or most aspects in the definition are invoked (Baumgartner et al., 2008), others study more narrowly defined frames for example, whether news stories focus on political processes or policy content (Binderkrantz & Christoffer, 2009). This study focuses on an aspect of interest group framing that has been central in recent scholarship: Do groups portray their policy positions as furthering the interests of their membership, other societal groups, or broader societal interests (Binderkrantz, 2019; Boräng & Naurin, 2015; Bruycker, 2016; Klüver et al., 2015)? This is consistent with Entman's emphasis on promoting a particular problem definition but does not necessarily include all aspects in the definition. Central to the distinction is that the same policy position can be portrayed differently—by pointing to the interests of group members or by emphasizing broader consequences.

Schattschneider (1975 [1969]) famously asserted that politics is about affecting the scope of conflicts. By pointing to broader consequences of policies, interest groups may enlist support from other groups and convince policymakers that the preferred policy of the group is beneficial from a larger perspective. A group of farmers may, for example, argue that restrictive environmental regulation of agriculture is detrimental to the societal economy rather than point to the costs of individual farmers. When participating in public debates, policy actors thus face incentives to frame their views in public terms (Ihlen et al., 2018; Rommetvedt, 2002, 2005).

A number of mechanisms may, on the other hand, lead groups to emphasize the concerns of their own membership or other specific societal groups. First, the political leverage of groups is related to their representation of constituencies such as workers, industries, or individuals. In many situations, groups may therefore gain from pointing to the direct effect of policies for members—especially when they represent constituencies that are likely to be seen as deserving fair treatment. In addition, interest groups do operate according not only to a “logic of influence” but also to “a logic of membership” (Berkhout, 2013). When groups appear in the news media, they are therefore seeking not only to affect politics but also to demonstrate to their members that they are pursuing their interests—and this may push them towards arguments of direct relevance for their members (Binderkrantz, 2019; Naurin, 2007).

The analytical framework for analyzing frames draws on previous work (Binderkrantz, 2019; Boräng et al., 2014) by distinguishing between (a) member-regarding frames, where groups point to the benefits or costs of their own membership; (b) other-regarding frames, where effects for other specific societal groups are in focus; (c) economy-regarding frames with a focus on broad economic aspects of policy; and (d) public-regarding frames addressing general societal consequences. The distinguishing factor is thus whether the group stresses concerns for its membership or other clearly identifiable societal groups or broader societal concerns. The last two categories both relate to the public good but distinguish between economic concerns and concerns of a more idealistic character.

1.2 The role of the policy area: Group appearances and frame use

This section discusses expected differences in the media presence of groups across policy areas. From the perspective of organized interests themselves, it is evident that their political activity relates to policy areas or even to more narrow issues. Although groups differ in the range of policy areas they engage in, all groups care more about some issue areas than others (Halpin & Binderkrantz, 2011). Most groups are established with a view to affect the public debate and policy decisions made within specific policy areas, and even the names of groups often indicate their specialization. After all, why would an association of tobacco companies seek influence on the school system, or a group of cancer patients try to affect immigration politics? A policy area perspective is thus important for understanding the political role of groups (Binderkrantz & Pedersen, 2015).

The emphasis on issue dynamics echoes Lowi's (1964) classic statement that policy determines policy—political mobilization depends on the type of policy in question. Wilson (1980) also emphasized this point in his discussion of the nature of costs and benefits associated with different types of policies. Typologies of policy areas inspired by this work have been used in the interest group literature to explain, for example, differences in group influence (Binderkrantz, Christiansen, & Pedersen, 2014). Although including typologies in empirical studies facilitates overall conclusions about policy-related dynamics, it only captures part of the policy-related variation in group mobilization and representation. As argued by Grossman (2013), issue areas may be hard to place in boxes, and differences in the politics of issue areas cannot readily be distilled into a few dimensions.

Policy dynamics affect group media representation as well as framing. Mobilization reflects the set of interests affected by policies as well as their ability to organize. Early scholars predicted that group mobilization would be most likely where costs were concentrated (Olson, 1965; Wilson, 1980), but later work has demonstrated how diffuse interests have also succeeded in mobilizing (Berry, 1999). Still, business interests are likely to be highly mobilized where policy is mainly about regulating business sectors. These may be opposed by, for example, environmental interest groups focusing on the societal benefits related to regulating business. Other policy areas may see labor and business mobilizing to affect, for example, labor market regulation, and yet other mobilization patterns are likely to characterize policy areas where the public sector is main responsible for production.

Patterns of media attentions are partly an effect of group mobilization and partly of media logics. Access to the news media has been described as based on an exchange logic—groups seek media attention, and reporters seek news stories and sources to include (Binderkrantz et al., 2015). Here, groups are at an advantage if they have a professional organization and an insider position in the political system because this provides them with relevant information and credibility (Thrall, 2006). Patterns of group appearance in the news media will thus not reflect the set of mobilized groups in any simple manner but will rather show concentrated attention on the most professional and privileged groups.

When it comes to frame use, two previous studies have found variation across policy areas. A study by Klüver and colleagues find differences in frame use depending on the EU Directorate General targeted by groups, and an aggregate analysis of framing in Denmark and the United Kingdom finds an effect of the type of policy domain (Binderkrantz, 2019; Klüver et al., 2015). These patterns partly reflect group mobilization as a relation between group type and frame use is also found. Groups that organize specific groups such as business firms, employees, or patients are more prone to frame their concerns with respect to these membership groups, whereas public interest groups—attracting members among those supporting group goals—are more likely to point to broad societal concerns (Binderkrantz, 2019; Boräng & Naurin, 2015; Klüver et al., 2015). To the extent that the groups appearing in the news media differ across policy areas, the dominance of different framing references will therefore differ.

In addition to the differences reflecting mobilization of different group types, the collective framing in each policy area is likely to reinforce differences across policy areas. Baumgartner and Mahoney (2008) have pointed to the dual levels of framing. Framing can be analyzed from the perspective of the individual actor and also at the aggregate level with a focus on how an issue is collectively defined. The nature of the policy in question may therefore shape not only group mobilization but also the types of frames seen as appropriate. As some areas, for example, come to be seen as about securing the rights of specific groups, this creates an incentive for all policy actors to frame their concerns in this direction. Based on this, it is expected that framing vary across policy areas beyond the effect associated with variation in the type of organized interests active in the areas.

2 RESEARCH DESIGN

The empirical analysis draws on a content analysis of interest group appearances in the Danish news media. Previous work has found variation in group coverage across newspapers of different political leaning (Binderkrantz et al., 2017), and the study therefore includes two papers of different political leaning: Jyllands-Posten and Politiken. Both papers are independent of political parties, but in terms of content and readership, Jyllands-Posten is right-leaning, and Politiken left-leaning on the traditional left–right dimension in politics. The period for the study is July 2009 to June 2010, and in this period, all front pages and half of all editions (first section and business section) were included. This decision was made to include a long time period in the study and thereby limit the possibilities that specific issues would dominate the news stories included.

The unit of analysis is individual interest groups appearing in news stories. The coding procedure included first identifying interest groups appearing in news stories and second the coding of a number of variables for each group appearance. To identify group appearances, student coders read all news stories and identified interest groups in these. The reliability of this step was tested in a double coding of 200 news stories, with a Cohen's kappa of 0.88.

- 1. member-regarding frames, where groups point to the benefits or costs of their own membership;

- 2. other-regarding frames, where effects for other specific societal groups are in focus;

- 3. economy-regarding frames with a focus on broad economic aspects of policy; and

- 4. public-regarding frames addressing general societal consequences.

All groups were coded in group type categories based on the INTERARENA coding scheme. This distinguishes between four types of economic groups: trade unions, business groups, institutional groups, and professional associations. In addition, it includes three types of citizen groups: identity groups, for example, associations based on shared identities not relating to the labor market or societal production, leisure groups, and public interest groups. The analysis excludes professional associations and leisure groups because they occur relatively infrequently in the data (<100 appearances across all policy areas). The intercoder reliability of the group categorization was tested by double coding of 100 groups with a Cohen's kappa of 0.91.

After an initial inspection of the data, six policy areas were chosen for analysis to ensure variation in type of policy as well as a high number of group appearances (for some collapsing two categories in the original coding). Table 1 presents the policy areas, their categorization, and expectations with respect to group appearances and frame use.

| Policy area | Type of policy area | Expectations: Group types | Expectations: Frame types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labor market policy | Business regulation | Business groups | Member-regarding |

| Trade unions | Economy-regarding | ||

| Business and consumer policy | Business regulation | Business groups | Member-regarding |

| Public interest groups | Public-regarding | ||

| Environmental and energy policy | Business regulation | Business groups | Member-regarding |

| Public interest groups | Public-regarding | ||

| Educational policy | Public production | Trade unions | Member-regarding |

| Institutional groups | Other-regarding | ||

| Identity groups | |||

| Health policy | Public production | Trade unions | Member-regarding |

| Institutional groups | Other-regarding | ||

| Identity groups | |||

| Justice and rights policy | General regulation | Identity groups | Other-regarding |

| Public interest groups | Public-regarding |

The policy areas have different characteristics expected to affect media representation and group framing. Labor market policy, business and consumer policy, and environmental and energy policy are all areas with heavy emphasis on regulation of business but differ in the set of interests that may mobilize to counter business. In labor market politics, the classic opponents are trade unions and trade associations, and debates may not only confront the concerns of these groups but also relate to broader economic concerns. In environmental and energy politics, business may meet opposition from primarily environmental groups pointing to broad public interests. Finally, in consumer politics, the relevant counterweight to business are groups representing broad citizen interests, for example, related to the role of consumer.

Two other policy areas exemplify public production policy: education politics and health politics. Here, groups of public employees and sectional groups representing welfare users are among the expected groups to mobilize. These may be accompanied by associations of the public institutions and authorities in charge of welfare production. In the Danish case, these differ across the two areas as education is largely organized by local authorities and independent state-regulated institutions, whereas regional authorities are responsible for large parts of the health care production. Debates in these areas are likely to center around the concerns of welfare beneficiaries. Finally, justice and rights politics is included as an example of general regulation. This may involve not only issues where general principles are at stake but also issues where, for example, the rights of specific groups are discussed.

- 1. As a measure of general group resources, the analysis includes the number of staff working with politics. To obtain linearity, this measure was logarithmically transformed and recoded to range from 0 to 1.

- 2. To analyze whether insider access to decision making affects media appearances, an index of privileged integration is included. This is based on group responses to a set of questions about how often the group is contacted by public officials, consulted on proposed regulation, and invited to participate in public commissions.

- 3. Finally, a measure gauges the extent to which groups are in political conflict and disagreement with other groups because this may push them towards pointing to broader consequences of their proposals.

2.1 Analyzing organized interests in the news media: Representation and framing

The empirical analysis focuses on two related questions: (a) the types of groups appearing in the news media in each of the selected policy areas and (b) the framing references made by the groups. For each policy area, the results of the quantitative content analysis are presented in tables, and the subsequent discussion provides illustrative examples of the frames used by groups. Table 2 presents results for the first three policy areas: labor market policy, business and consumer policy, and environmental and energy policy.

| Group type | Media appearances | Member-regarding | Other-regarding | Economy-regarding | Public-regarding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor market policy | |||||

| Trade unions | 72.4 | 62.5 | 16.9 | 15.9 | 4.7 |

| Business groups | 21.7 | 37.6 | 23.2 | 29.6 | 9.6 |

| Institutional groups | 4.0 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Identity groups | 1.3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Public interest groups | 0.6 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| All groups | N = 631 | 54.8 | 20.2 | 19.3 | 5.7 |

| Business and consumer policy | |||||

| Trade unions | 9.7 | 69.4 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 2.0 |

| Business groups | 70.8 | 55.3 | 16.7 | 21.8 | 6.2 |

| Institutional groups | 0.8 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Identity groups | 5.2 | 75.0 | 14.3 | 7.1 | 3.6 |

| Public interest groups | 13.5 | 28.6 | 46.8 | 7.8 | 16.9 |

| All groups | N = 600 | 53.6 | 20.8 | 18.2 | 7.4 |

| Environment and energy | |||||

| Trade unions | 3.5 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Business groups | 36.9 | 42.9 | 7.9 | 11.1 | 38.1 |

| Institutional groups | 7.6 | 53.3 | 13.3 | 0.0 | 33.3 |

| Identity groups | 0.5 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Public interest groups | 51.5 | 9.4 | 10.4 | 1.0 | 79.2 |

| All groups | N = 198 | 25.1 | 9.5 | 4.5 | 60.9 |

- Note. The second column shows the percentage of each group type appearing in news stories. The four other columns show the percentage of different framing references for each group type. Framing references for group types with less than 5% appearances are omitted.

It is evident from the table that labor market policy is an issue mainly debated by trade unions and business groups. These types of groups account for more than 90% of all media attention. In addition, institutional groups have some presence in this area—most likely in their capacity as employers in the public sector. Trade unions mainly framed their concerns as related to membership interests but also occasionally used references to other groups or the economy at large. Business groups diversified their arguing to a larger extent and frequently referred to both membership concerns, other groups and the economy.

Among the issues debated in this area were the wage negotiations for the private sector. These were affected by the economic crisis, and employers stressed the need to constrain wages to secure the competitiveness of Danish companies. This exemplifies the use of a framing emphasizing broad economic aspects of a position that also directly benefits business group members. Trade unions on their side largely accepted the agenda of limited pay raise and turned their attention to other issues such as protecting their members from competition from nonorganized labor and the negotiation rights of unions—issues they framed as discriminating their membership: “Our members will simply not accept this discriminating rule, and this vote is a strong reprimand to employers who categorically and stubbornly refused to negotiate our demands” (Trade union chairperson). 0

A different pattern of interest group representation characterizes news stories about business and consumer issues. Here, business groups dominate with about 70% of all appearances, whereas public interest groups account for 13.5% and trade unions for 10% of attention. Across all policy areas, this is the area where business groups are most likely to point to membership interests—in 55% of the cases. In a debate about tax credits for companies, business associations, for example, pointed to the risk of their members going out of business: “Some firms may go bankrupt, and others will have to say no to possible customers.” as expressed by a representative of Danish Industry. 1 Although this could also have been framed with focus on the detrimental consequences for the economy at large, the group emphasized the immediate effects for members.

On their side, public interest groups were most likely to point to consequences for nonmember groups. For example, the Danish Consumer Council pointed out how families with kids might benefit from liberalizing regulation of business hours. When trade unions entered these debates, their arguments usually took their members as the point of departure. Their emphasis in the discussion of business hours was, for example, on the negative effects for union members working in the sector.

In news stories about environment and energy, public interest groups account for half of all group appearances and are most often accompanied by business interest—37%— whereas institutional groups appear in about 8% of the cases. Environment and energy stands out as the policy area where public interest frames are most commonly used. Environmental groups are frequent participants in these debates stressing concerns related to the environment and climate. Interestingly, business groups also use public-regarding framing in almost 40% of the cases. This indicates how group type and policy area interact in shaping framing. Still, the most common frame used by business is member-regarding. In many instances, it is evident that business groups seek to balance these concerns as exemplified by the Danish Shipowner's Association stressing its support for environmental regulation—as long as it applies also to competing companies from other countries. 2

Table 3 presents group appearances and frame use for educational policy, health policy, and justice and rights policy. Education and health are among the key areas of the welfare state, and in Denmark, public providers are responsible for most activity in these areas—although private alternatives exist. In both areas, three types of groups are most visible: institutional groups, trade unions, and identity groups. Together, these represent the authorities responsible for welfare delivery, the employees in the sector, and the beneficiaries of welfare services.

| Group type | Media appearances | Member-regarding | Other-regarding | Economy-regarding | Public-regarding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational policy | |||||

| Trade unions | 39.7 | 38.1 | 42.3 | 9.3 | 10.3 |

| Business groups | 7.0 | 16.7 | 22.2 | 38.9 | 22.2 |

| Institutional groups | 30.9 | 29.1 | 51.9 | 8.9 | 10.1 |

| Identity groups | 21.3 | 49.1 | 38.6 | 8.8 | 3.5 |

| Public interest groups | 1.1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| All groups | N = 272 | 36.0 | 43.5 | 11.1 | 9.5 |

| Health policy | |||||

| Trade unions | 23.3 | 47.6 | 28.6 | 6.3 | 17.5 |

| Business groups | 13.0 | 40.5 | 38.1 | 7.1 | 14.3 |

| Institutional groups | 28.1 | 24.1 | 45.8 | 16.9 | 13.3 |

| Identity groups | 30.5 | 41.7 | 45.8 | 1.0 | 11.5 |

| Public interest groups | 5.1 | 26.7 | 40.0 | 0.0 | 33.3 |

| All groups | N = 331 | 37.1 | 40.8 | 7.4 | 14.7 |

| Justice and rights policy | |||||

| Trade unions | 37.0 | 49.3 | 31.5 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Business groups | 16.7 | 46.9 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 21.9 |

| Institutional groups | 6.0 | 41.7 | 16.7 | 33.3 | 8.3 |

| Identity groups | 11.6 | 40.0 | 45.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 |

| Public interest groups | 28.7 | 6.8 | 68.2 | 0.0 | 25.0 |

| All groups | N = 216 | 37.0 | 38.1 | 9.4 | 15.5 |

- Note. The second column shows the percentage of each group type appearing in news stories. The four other columns show the percentage of different framing references for each group type. Framing references for group types with less than 5% appearances are omitted.

In educational policy, trade unions frequently refer to other societal groups. In a heated debate about the use of national test in schools, the chairperson of the school teachers association argued: “It's better to let teachers evaluate the level of pupils because they can choose the test that works best for each individual pupil.” 2 Here, the professional discretion of teachers is described as a means to help children. On their side, the institutional groups—with Local Government Denmark as the main actor—also present most of their suggestions as raising the quality of the education of each individual kid. Identity groups active in this domain include associations of parents as well as students, and among these, the most dominant frame is simply to point to the interests of their own membership.

Debates about health care are relatively similar to the educational area. Trade unions appear less often in this area, but when they do, they are more likely to point to the interests of their membership. In health care, the concerns of health care professionals and patients are often portrayed as interlinked as when a report found 40% of younger doctors to have increased their workload: “We are asked to produce more and more, without necessarily getting more resources […]. Of course this affect treatment of patients” (Chairman of Young Doctor's Association). 3 Among the analyzed policy areas, identity groups have their highest presence in this area. These groups point mainly to their own membership interests or to other specific groups.

In justice and rights policy, all group types appear at least 5% of the time, but the most frequent participants are trade unions and public interest groups. This reflects that both individual and collective rights are regularly debated. Trade unions participate in debates, for example, about whistleblowers, criminal sanctions, and legal protection of minorities, where they express concerns related to their own membership. This is also the case for most business groups appearing in this area. The most active public interest groups in these debates are groups working with social affairs or human rights. These groups typically act as advocates for vulnerable individuals or groups when participating in these debates—as demonstrated by the high share of other-regarding frames in their communication.

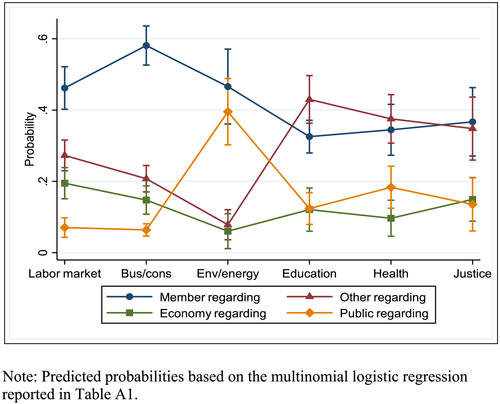

The analysis has demonstrated variation in group representation and frame use between policy areas. To test the extent to which variation in frame use is related to variation in the types of groups active or to policy area dynamics, a multivariate analysis of frame use is conducted. Here, control variables at the group level are included: group resources, the level of privileged position, and the amount of conflict with other groups experienced. Figure 1 displays the predicted probabilities of frame use for each policy area on the basis of a multinomial logistic regression. Because each group may appear multiple times in the analysis, standard errors are clustered with respect to individual groups. Table A1 reports regression results.

The analysis confirms the patterns described above. Some policy areas—notably labor market politics and business and consumer politics—are mainly discussed with references to group members contrasting, for example, the interests of business and labor. Environmental and energy policy stands out as more prone to public-regarding arguments than any other policy area, although membership concerns are also voiced most often here. The remaining areas—education, health, and justice and rights—are characterized by much focus on the societal groups in focus of, for example, welfare state production. The analysis thus demonstrates that even when controlling for group type, differences across policy area persist.

3 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This paper analyzed interest group representation and framing in the news media. Where previous studies have focused on aggregate patterns of interest group representation and communication (Binderkrantz et al., 2015; Binderkrantz & Pedersen, 2019; Boräng & Naurin, 2015; Thrall, 2006), the analysis centered on the importance of the policy context for group appearances and frame use. It demonstrated how not only the patterns of group appearance but also the types of frames used to present group positions vary greatly across policy areas.

Studies of interest group framing frequently focus on whether groups present their claims as furthering the interests of their own membership or argue that other societal groups or even society at large may benefit from accommodating the group (Binderkrantz, 2019; Boräng & Naurin, 2015; Klüver et al., 2015). Drawing on this conceptualization of framing, the study has confirmed previous findings of variation across group type in frame references. In most policy areas, business groups are prone to point to member interests, whereas public interest groups are more likely to frame their concerns in broad terms or as helping nonmembership groups.

It is also clear from the analysis that frame use reflects not only the group type but also the policy area in question. For example, business groups participating in news stories on energy and environment are more likely to use nonmembership frames than business groups appearing in stories on labor market policy. These findings demonstrate the linkage between aggregate dynamics related to the policy area in question and the frames individual advocates use (Baumgartner & Mahoney, 2008). Notably, the differences found are an effect not only of the patterns of group mobilization but also of the policy issue dynamics. Depending on the policy area in question, the same type of group thus shows different framing preferences.

The analysis also shows that public debates are in fact not always carried out in public terms (Naurin, 2007; Schattschneider, 1975). Organized interests also frequently point to the interests of their own membership or to other specific societal groups. This pattern may be seen as a result of both policy dynamics and the need for groups to balance concerns for affecting policy and appealing to their own members (Berkhout, 2013). From a democratic perspective, it is interesting that the type of interests and arguments made in public debates depend largely on the policy area in question. Evaluations of the democratic quality of public debate therefore need to consider not only aggregate patterns but also differences across policy areas.

Empirically, the analysis focused on Denmark. In a comparison with the United Kingdom, Danish interest groups have been found more likely to frame their viewpoints in relation to membership and less likely to point to broad public concerns (Binderkrantz, 2019). Although policy dynamics are likely to be present in other contexts than the Danish, the specific levels of frame use are thus likely to vary. Further studies may investigate this and would also be required to obtain deeper insights in the processes shaping group decisions about when and how to enter public debates.

Appendix A:

| Coefficient (SE) | p > z | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Member-regarding | (Base outcome) | ||

| Other-regarding | Labor market policy | (Base outcome) | |

| Business and consumer policy | −0.56 (0.23) | .015 | |

| Environmental and energy policy | −1.19 (0.41) | .004 | |

| Educational policy | 0.90 (0.17) | .000 | |

| Health policy | 0.71 (0.21) | .001 | |

| Justice and rights policy | 0.54 (0.32) | .090 | |

| Trade union | (Base outcome) | ||

| Business group | 0.47 (0.21) | .021 | |

| Institutional group | 1.09 (0.18) | .000 | |

| Identity group | 0.42 (0.25) | .094 | |

| Public interest group | 2.43 (0.32) | .000 | |

| Privileged position | −0.54 (0.29) | .067 | |

| Political employees | 0.32 (0.32) | .305 | |

| Conflict | 0.12 (0.10) | .270 | |

| Constant | −1.16 (0.30) | .000 | |

| Economy-regarding | Labor market policy | (Base outcome) | |

| Business and consumer policy | −0.54 (0.28) | .052 | |

| Environmental and energy policy | −1.17 (0.48) | .016 | |

| Educational policy | −0.12 (0.27) | .662 | |

| Health policy | −0.40 (0.35) | .256 | |

| Justice and rights policy | −0.02 (0.31) | .944 | |

| Trade union | (Base outcome) | ||

| Business group | 0.89 (0.30) | .003 | |

| Institutional group | 0.93 (0.34) | .007 | |

| Identity group | −0.26 (0.34) | .450 | |

| Public interest group | 0.54 (0.47) | .247 | |

| Privileged position | −0.98 (0.50) | .050 | |

| Political employees | 1.59 (0.50) | .001 | |

| Conflict | 0.26 (0.18) | .135 | |

| Constant | −2.01 (613) | .001 | |

| Public-regarding | Labor market policy | (Base outcome) | |

| Business and consumer policy | −0.40 (0.35) | .259 | |

| Environmental and energy policy | 1.83 (0.40) | .000 | |

| Educational policy | 1.02 (0.21) | .000 | |

| Health policy | 1.36 (0.31) | .000 | |

| Justice and rights policy | 0.97 (0.45) | .031 | |

| Trade union | (Base outcome) | ||

| Business group | 0.54 (0.37) | .151 | |

| Institutional group | 0.38 (0.32) | .247 | |

| Identity group | −0.44 (0.40) | .264 | |

| Public interest group | 2.64 (0.42) | .000 | |

| Privileged position | −1.0 (0.61) | .095 | |

| Political employees | 1.60 (0.56) | .004 | |

| Conflict | 0.36 (0.14) | .009 | |

| Constant | −3.27 (0.40) | .000 |

- Note. N = 1,756; pseudo R2 = .13. Standard errors clustered for groups.

Biography

Anne Skorkjær Binderkrantz is Professor of Political Science, Aarhus University. Her research focuses on the political role of interest groups, political elites, and public governance. She has published in journals such as the Journal of European Public Policy, British Journal of Political Science, and European Journal of Political Research. [[email protected]]

REFERENCES

- 0 Wage earners accept historically low salary [Lønmodtagere siger ja til historisk lav løn], Politiken, April 21, 2010.

- 1 No to a prolonged tax credit [Nej til forlænget momskredit]. Jyllands-Posten, August 13, 2009.

- 2 Shipowners ready for climate demands [Rederier klar til klimakrav], Jyllands-Posten, October 2, 2009.

- 2 Teachers: Testing leads to failure [Lærere: Test giver nederlag], Jyllands-Posten, November 28, 2009.

- 3 Busy doctors raise the likelihood of error [Travlhed blandt læger øger risikoen for fejl], Politiken, July 29, 2009.