Overweight and Obesity Impair Academic Performance in Adolescence: A National Cohort Study of 10,279 Adolescents in China

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to examine the associations of overweight and obesity (ov/ob) and changes in weight status with academic performance among Chinese adolescents.

Methods

Self-reported weight and height were collected from adolescents (n = 10,279) each year from seventh grade (baseline, 2013-2014) to ninth grade (2015-2016). Academic performance included standardized scores on math, Chinese, and English examinations and responses to a school-life experience scale.

Results

All adolescents with ov/ob had lower academic performance than their counterparts without overweight (β = −0.46 to −0.08; P < 0.05), except for school-life experience for boys. All adolescents with obesity had lower academic performance than their counterparts without obesity (β = −0.46 to −0.17; P < 0.01), except for English test scores for boys. Changes in weight status between grades 7 and 9 impacted academic performance at grade 9. Adolescents with ov/ob throughout grades 7 to 9 and those who developed ov/ob from normal weight had lower test scores (β = −0.80 to −0.25; P < 0.05) than those who maintained normal weight. Those who developed ov/ob after having normal weight had poorer school-life experiences (β = −0.55 to −0.25; P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Ov/ob and maintaining and developing ov/ob had adverse academic impacts on adolescents. Relevant stakeholders should consider detrimental impacts of obesity on academic outcomes.

Study Importance

What is already known?

- ► Some cross-sectional studies and limited longitudinal research have indicated that overweight or obesity (ov/ob) negatively affects children’s and adolescents’ academic performance in Western countries, but there is limited research on the influence of ov/ob on poor academic performance in adolescents in developing countries, including China.

- ► In China, about 20% of children and adolescents have ov/ob, and the rate continues to increase.

What does this study add?

- ► Using data collected from a nationally representative cohort of middle school students in China, we found the students with ov/ob had lower standardized subject test scores and school-life experience scale scores than those without ov/ob.

- ► We found that changes in body weight status during early adolescence significantly predicted academic performance.

How might these results change the direction of research?

- ► Future studies need to examine the mediation mechanisms between ov/ob and academic performance and then develop intervention programs to prevent childhood obesity and the negative impact of obesity on students’ academic performance.

Introduction

The prevalence of childhood obesity is high globally ((1-4)). In China, 28.2% of adolescents had overweight or obesity (ov/ob) in 2014 ((5, 6)). In addition to its well-known physical health risks, ov/ob has been found to have detrimental effects on child academic performance ((7, 8)). Children spend most of their time in school, and the effects of ov/ob may manifest in various facets of their academic performance. In Chinese culture, education has long been and remains to be seen as a valued tool for social upward mobility, and academic performance is highly valued ((9)). Rapid social changes and implementation of the One-Child Policy have contributed to elevated academic competition. Schools and parents have high educational standards and aspirations, emphasizing academic skills above all other skills ((10, 11)). Understanding the impacts of ov/ob on adolescents’ academic performance may have major implications in China; however, no nationally representative cohort study has been conducted.

Existing evidence for the impacts of ov/ob on academic performance among adolescents has been limited and inconsistent. A 2017 systematic review that included 34 studies published before 2016 found the causal links between ov/ob and academic performance to be uncertain; studies all relied on data from Western countries, most of the studies were of cross-sectional design, there was failure to control for important confounders, and adequate power analyses were absent ((12)). Of the 11 longitudinal studies included, only 2 examined the effects of ov/ob on academic performance in adolescents. In one study of adolescents in the UK, girls who had obesity at 11 years old had lower English, math, and science test scores at ages 11, 13, and 16 years. In addition, girls who went from having overweight at age 11 years to having obesity at age 16 years and girls with ov/ob throughout the same period had lower academic achievements at age 16 after adjusting for covariates (e.g., age) ((13)). Similarly, in a longitudinal study of Finnish adolescents, obesity was found to be associated with lower grade point averages after adjusting for covariates (e.g., maternal education) ((14)). While these findings indicate that ov/ob negatively affects adolescents’ academic performance in Western settings, it is unknown what similar studies would yield given China’s unique societal, cultural, and developmental contexts.

With respect to body weight status change during adolescence, one study found that about 9% of adolescents had chronic ov/ob and 11% developed obesity during early adolescence (15). Those developed obesity during adolescence were more likely to experience poorer psychosocial health ((15)). Most existing studies have focused on academic achievement, but adolescent experiences and attitudes related to school are arguably important indicators of academic performance as well ((16)). For example, more positive “school-life experiences” were observed to significantly contribute to adolescent academic success and performance ((17)). However, to our knowledge, no studies have undertaken a comprehensive examination of such potential effects.

Using Chinese national cohort data for adolescents between grade 7 and grade 9, this study (1) described differences in academic performance (standardized subject test scores and school-life experience scores) by weight status (Aim 1) and (2) examined the effects of having ov/ob and changes in weight status on academic performance (Aim 2). We hypothesized that having ov/ob would negatively affect academic performance. Also, we hypothesized adolescents with ov/ob throughout grade 7 to grade 9 and those who developed ov/ob during follow-up would have poorer academic performance at grade 9 compared with adolescents maintaining normal weight status.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study analyzed data from the middle school cohort of the China Education Panel Survey (CEPS). The CEPS is a national cohort study representative of seventh-graders enrolled in the 2013-2014 academic year and it was designed to document attributes of the developmental and educational experiences of Chinese adolescents ((18-20)). The CEPS study utilized a multistage stratified design in which counties (or equivalent administrative districts), schools, and classes were the primary, the secondary, and the tertiary sampling units, respectively. Primary sampling units were stratified by region and migrant population size, with oversampling of counties in Shanghai or other areas with a high migrant population. Four schools were drawn from each sampled county using the probability proportional to size method. Two classrooms were sampled from each school. In total, 28 counties were selected, composed of 112 schools and 224 classrooms of seventh-graders. All students in sample classrooms were asked to complete the self-administered questionnaire administered by local survey teams composed of trained researchers from provincial universities or provincial institutes of social sciences. Survey weights were developed by the CEPS team to address the unequal probabilities of selection ((18)).

Data collected at grade 7 (baseline, the 2013-2014 academic year), grade 8 (the 2014-2015 academic year), and grade 9 (the 2015-2016 academic year) on students’ and parents’ demographic characteristics, students’ weight status, and students’ academic performance were analyzed. The sample sizes were 10,279 for seventh-graders (boys: 5,310; girls: 4,773; gender unreported: 196), 9,449 for eighth-graders (missing rate for all adolescents = 8.1%, number of boys: 4,842; girls: 4,436; gender unreported: 171), and 8,232 for ninth-graders (missing rate for all = 12.9%, number of boys: 4,126; girls: 4,001; gender unreported: 105). All the nonmissing data for variables of interest were included in the final data analysis. For longitudinal analyses, participants with complete data for all 3 years were included (n = 8,127) (Supporting Information Figure S1).

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Renmin University. Children signed assent forms and their parents signed consent forms for participation in the study. Students were not provided incentives to participate.

Key study variables and measurements

Outcome variables

The following two types of indicators of academic performance were used: standardized subject test scores and responses on a school-life experience scale.

For standardized subject test scores, annual midterm exam scores for math, Chinese, and English in grades 7 to 9 were examined as outcome measures, which were abstracted from school administrative files by trained CEPS teams ((19)). These three subjects are regarded as foundational courses in the current Chinese educational system. Test scores were standardized (mean [SD]: 0 [1]) by subtracting the mean of 70 from the original scores and dividing by an SD of 10; this is the most used method for standardizing test scores in the Chinese educational system. These standardized subject test scores are comparable across adolescents both within the same and across different academic years ((19)).

School-life experience scores were measured by a nine-item Chinese language scale created by the CEPS team. Students were asked to indicate their level of agreement on a 4-point Likert scale that ranged from “strongly disagree” = 1 to “strongly agree” = 4. Responses reflected students’ experiences and attitudes regarding their school life and included general feelings about school life (e.g., I feel bored in this school) as well as perceptions related to specific school aspects, i.e., relationships with teachers and other students and participation in school activities. Scale scores were calculated by summing all items (four items were reverse scored), and total scores ranged from 9 to 36. Higher scores indicated more positive experiences and perceptions regarding one’s school life. Cronbach α of this scale was 0.70.

Exposure variables

BMI was calculated using student self-reported body weight divided by self-reported height squared (kilograms per meter squared). Ov/ob was defined based on age- and gender-specific BMI cutoff points in the “WS/T 586-2018 Screening for overweight and obesity among school-age children and adolescents,” which is a set of national Chinese criteria recommended by the National Health Commission of China for use in youth 6 to 18 years old (WS/T 586-2018) ((21)).

Dummy variables representing changes in weight status were constructed and entered as predictors in mixed-effects models. Adolescents were classified into one of the following five groups for weight change between grade 7 (baseline) and grade 9 (follow-up) (where change was defined as the difference between baseline and follow-up point): maintained normal weight status throughout (reference), had ov/ob throughout (including remained with ov/ob or developed overweight from obesity), developed ov/ob from normal weight, developed obesity from overweight, and developed normal weight from ov/ob.

Covariates

Covariates included students’ demographic and health and family characteristics, including age (in years), gender, ethnicity (Han, non-Han), being a single child (yes, no), mother’s and father’s education level (≤ junior middle school = 1, senior middle school or vocational schools = 2, ≥ college = 3), and perceived household socioeconomic status (lower income = 1, middle class = 2, wealthy = 3).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. χ2 tests (for categorical variables) and t tests (for continuous variables) were used to test for gender differences at baseline (grade 7).

For Aim 1, t tests were used to compare academic performance between children without overweight and those with ov/ob at grade 7, grade 8, and grade 9.

For Aim 2, mixed-effects models were used to examine effects of ov/ob on academic performance and whether changes in weight status between grade 7 and grade 9 affected outcomes at grade 9. Effect sizes were presented as beta coefficients with a standard error (SE). Gender-stratified analysis was conducted to examine potential differences in these associations. Mixed-effects models adjusted for random effects for the child and school.

Stata 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas) was used for data analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Mixed-effects modeling was used to account for clustering effects.

Results

Characteristics of adolescents

Among the 10,279 adolescents (mean age: 13.1 years) present at baseline in 2013, the combined prevalence of ov/ob was 23.4% (boys vs. girls: 28.7% vs. 17.8%, P < 0.001), and the prevalence of underweight was 13.6% (boys vs. girls: 16.4% vs. 10.5%). A total of 43.0% were the single child in their family, and 70% perceived their family’s present household economic condition as middle class (Table 1).

| All (n = 10,279) | Boys (n = 5,310) | Girls (n = 4,773) | P for sex differencea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 13.1 (0.8) | 13.1 (0.8) | 13.0 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | 0.181 | |||

| Han | 90.9 | 91.3 | 90.6 | |

| Non-Han | 9.1 | 8.7 | 9.4 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.4 (3.4) | 18.8 (3.7) | 18.1 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Overweight/obesity | 23.4 | 28.7 | 17.8 | <0.001 |

| Underweight | 13.6 | 16.4 | 10.5 | <0.001 |

| Weight status changes between ages 13 and 15 years, during 2013-2015 | <0.001 | |||

| Remained normal weight status | 68.7 | 63.7 | 73.8 | |

| Remained with overweight/obesity | 9.0 | 11.7 | 6.3 | |

| Overweight/obesity from normal weight | 8.3 | 7.7 | 8.8 | |

| Obesity from overweight | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.7 | |

| Normal weight from overweight/obesity | 12.7 | 14.9 | 10.4 | |

| Single child | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 43.0 | 45.7 | 40.6 | |

| No | 57.0 | 54.3 | 59.5 | |

| Mother's highest education | 0.241 | |||

| ≤ Junior middle school | 64.1 | 64.0 | 63.4 | |

| Senior middle school or vocational school | 22.6 | 22.9 | 22.4 | |

| ≥ College | 13.3 | 13.1 | 14.3 | |

| Father’s highest education | 0.030 | |||

| ≤ Junior middle school | 57.3 | 58.2 | 56.0 | |

| Senior middle school or vocational school | 24.3 | 26.4 | 26.8 | |

| ≥ College | 18.4 | 15.4 | 17.2 | |

| Perceived household economic status | <0.001 | |||

| Lower income | 21.0 | 21.9 | 19.6 | |

| Middle class | 70.0 | 68.0 | 72.7 | |

| Wealthy | 9.0 | 10.1 | 7.7 |

- a P value based on χ2 test for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables across genders.

- Overweight and obesity and underweight defined according to “WS/T 586-2018 Screening for overweight and obesity among school-aged adolescents and adolescents.” Total sample size was 10,279, but 196 were missing on gender, so total number of boys and girls was 10,083. Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance.

Adolescents were further grouped based on changes in their weight status between grade 7 and grade 9 as follows: (1) 68.7% maintained normal weight status (boys: 63.7%, girls: 73.8%,), (2) 9.0% remained with ov/ob (boys: 11.7%, girls: 6.3%), (3) 8.3% developed ov/ob after having normal weight (boys: 7.7%, girls: 8.8%), (4) 1.3% developed obesity from overweight (boys: 1.9%, girls: 0.7%), and (5) 12.7% became normal weight from ov/ob (boys: 14.9%, girls: 10.4%) (Table 1).

Cross-sectional comparisons of academic performance between adolescents without overweight and with ov/ob

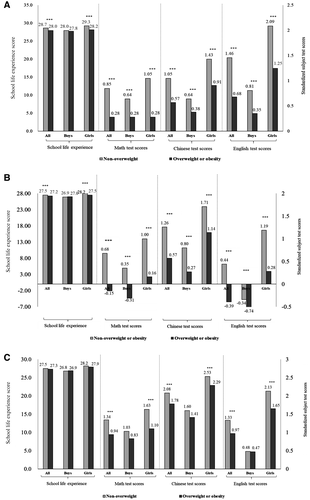

Figure 1 shows differences in academic performance indicators by weight status separately by each academic year.

Standardized subject test scores

Test scores of adolescents with ov/ob were significantly lower than those of adolescents without overweight at grade 7 and grade 8 for all adolescents (P < 0.001), boys (P < 0.001), and girls (P < 0.001). At grade 9, however, differences in standardized scores for the three courses between ov/ob groups and groups without overweight were significant only for all adolescents (P < 0.001) and girls (P < 0.05) but not for boys.

School-life experience scale scores

Compared with adolescents without overweight, school-life experience scores of adolescents with ov/ob were significantly lower at grade 7 (28.0 vs. 28.7, P < 0.001) and grade 8 (27.2 vs. 27.5, P = 0.002) but not at grade 9. Similarly, school-life experience scores of girls with ov/ob were significantly lower than scores of girls without overweight at grade 7 (29.3 vs. 28.2, P < 0.001) and grade 8 (28.2 vs. 27.5, P < 0.001) but not at grade 9. However, no significant differences were observed in school-life experience scores by weight status for boys in each grade.

Longitudinal data analyses: effects of ov/ob on academic performance indicators by gender

Standardized subject test scores

Adolescents with ov/ob had lower math (β = −0.20, P < 0.001), Chinese (β = −0.23, P < 0.001), and English (β = −0.08, P < 0.05) test scores than those in the nonoverweight group after adjusting for covariates (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity). Similar findings were found for boys (β = −0.24 to −0.11, P < 0.05) and girls (β = −0.26 to −0.13, P < 0.05), again after adjusting for covariates. Adolescents with obesity had lower math and Chinese test scores compared with adolescents without obesity overall as well as boys and girls (βs ranged from −0.36 to −0.23, P < 0.01). For English test scores, however, only girls with obesity had significantly lower scores (β = −0.17, P < 0.01) (Table 2).

| Math | Chinese | English | School-life experience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight or obesity (vs. nonoverweight) | ||||

| All | −0.20 *** (0.04) | −0.23 *** (0.03) | −0.08 * (0.04) | −0.27 *** (0.07) |

| Gender | ||||

| Boys | −0.23 *** (0.05) | −0.24*** (0.04) | −0.11 * (0.05) | −0.14 (0.09) |

| Girls | −0.22 *** (0.06) | −0.26 *** (0.04) | −0.13 * (0.05) | −0.46 *** (0.10) |

| Obesity (vs. nonobesity) | ||||

| All | −0.23 *** (0.05) | −0.29 *** (0.03) | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.43 *** (0.08) |

| Gender | ||||

| Boys | −0.26 *** (0.06) | −0.30 *** (0.04) | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.41 *** (0.11) |

| Girls | −0.26 *** (0.07) | −0.34 *** (0.04) | −0.17 ** (0.06) | −0.46 *** (0.12) |

- * P < 0.05.

- ** P < 0.01.

- *** P < 0.001.

- Variable definition: overweight and obesity defined based on “WS/T 586-2018 Screening for overweight and obesity among school-aged adolescents and adolescents” recommended by National Health Commission of China; 0 = nonoverweigh t, 1 = overweight or obesity.

- For standardized subject test scores, higher scores indicate better academic achievement, ranging from −3 to 3.

- For school-life experience scores, total score of 9-item scale calculated with four items reverse scored, with higher scores indicating better school-life experience; total score ranged from 9 to 36.

- Beta and SE based on linear mixed-effects models using standardized subject test scores and school-life experience scores as dependent variables.

- Covariates included age, gender, ethnicity, being a single child, mother’s and father’s education, and perceived household economic status.

- In gender-stratified analyses, the same covariates were adjusted for except gender.

- Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance.

School-life experience scale scores

Adolescents with ov/ob had lower school-life experience scores than adolescents without overweight, both overall (β = −0.27, P < 0.001) and for girls (β = −0.46, P < 0.001) after adjusting for covariates. This was not observed for boys. Adolescents with obesity had lower school-life experience scores compared with adolescents without obesity after adjusting for the same covariates for adolescents overall, boys, and girls (βs ranged from −0.46 to −0.41, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Supporting Information Table S1 and Table S2 shows interaction analyses between weight status and gender on standardized subject test scores and school-life experience scores.

Longitudinal data analyses: effects of changes in weight status over grades 7 to 9 (between 13 and 15 years old) on academic performance at grade 9 (15 years old)

Standardized subject test scores

All adolescents, boys, and girls with ov/ob or who became normal weight after having ov/ob between grade 7 and grade 9 had lower math, Chinese, and English test scores at grade 9 compared with those who maintained normal weight status (β = −0.83 to −0.25, P < 0.01), adjusting for covariates. All adolescents and boys who developed ov/ob after having normal weight had lower math and Chinese test scores (βs ranged from −0.50 to −0.25, P < 0.05); these associations were not significant for girls. Changing from obesity to overweight did not have significant effects on standardized subject test scores (Table 3).

| Math | Chinese | English | School-life experience | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (Model 1) | Boys (Model 2 ) | Girls (Model 3 ) | All (Model 4) | Boys (Model 5) | Girls (Model 6) | All (Model 7) | Boys (Model 8) | Girls (Model 9) | All (Model 10) | Boys (Model 11) | Girls (Model 12) | |

| Maintained normal weight status (reference) | ||||||||||||

| Remained with overweight/obesity | −0.71 *** (0.12) | −0.66 * (0.16) | −0.80 *** (0.18) | −0.36 *** (0.06) | −0.37 *** (0.09) | −0.39 *** (0.09) | −0.58 *** (0.11) | −0.54 *** (0.15) | −0.77 *** (0.16) | −0.21 (0.17) | −0.02 (0.21) | −0.42 (0.26) |

| Developed overweight/obesity from normal weight | −0.44 * (0.16) | −0.50 * (0.24) | −0.37 (0.22) | −0.25 * (0.09) | −0.32 * (0.13) | −0.19 (0.11) | −0.19 (0.15) | −0.27 (0.22) | −0.13 (0.19) | −0.53 ** (0.17) | −0.55 * (0.25) | −0.45 * (0.22) |

| Developed obesity from overweight | −0.07 (0.29) | 0.01 (0.36) | −0.26 (0.50) | −0.16 (0.15) | −0.24 (0.20) | −0.09 (0.24) | −0.20 (0.26) | −0.28 (0.33) | −0.20 (0.43) | −0.02 (0.40) | 0.11 (0.9) | −0.34 (0.72) |

| Developed normal weight from overweight/obesity | −0.68 *** (0.10) | −0.60 *** (0.14) | −0.80 *** (0.15) | −0.35 *** (0.05) | −0.25 ** (0.08) | −0.52 *** (0.07) | −0.70 *** (0.09) | −0.64 *** (0.13) | −0.83 *** (0.13) | −0.37 * (0.14) | −0.27 (0.19) | −0.58 ** (0.22) |

- * P < 0.05.

- ** P < 0.01.

- *** P < 0.001.

- Variable definitions: overweight and obesity defined based on “WS/T 586-2018 Screening for overweight and obesity among school-aged adolescents and adolescents” recommended by National Health Commission of China.

- For standardized subject test scores, higher scores indicate better academic achievement.

- For school-life experience scores, total score of 9-item scale calculated with four items reverse scored, with higher scores indicating better school-life experience.

- Beta and SE based on linear mixed-effects models using standardized academic performance and school-life experience scores as dependent variables and five weight status change categories as independent variables adjusting for covariates (age, gender, ethnicity, being a single child, mother’s and father’s education, perceived household income status). In gender-stratified analyses, same covariates were adjusted for except for gender.

- Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance.

School-life experience scale scores

After adjusting for covariates, analyses of all adolescents, boys, and girls found that those who developed ov/ob at grade 9 after having normal weight at grade 7 had lower school-life experience scores (βs ranged from −0.55 to −0.45, P < 0.05) than those who maintained normal weight. In analyses of all adolescents and girls, those who became normal weight after having ov/ob had lower school-life experience scores (β = −0.37 and −0.58, respectively, P < 0.05). Maintaining ov/ob and changing to having obesity from overweight did not significantly affect school-life experience scores (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first nationally representative cohort study examining the effects of ov/ob and changes in weight status on academic performance in China. Our findings support our hypotheses. We found that having ov/ob had adverse impacts on middle school students’ standardized subject test scores and school-life experience scale scores, and the effects seemed greater in girls than in boys. Additionally, changes in weight status between grade 7 and grade 9 significantly predicted academic performance at grade 9. Generally, adolescents who had ov/ob throughout or developed ov/ob from normal weight had lower academic performance at grade 9 compared with those who maintained normal weight status. Interestingly, those who attained normal weight status at grade 9 after having ov/ob at grade 7 had lower academic performance at grade 9.

Adolescents with ov/ob had lower math, Chinese, and English test scores after controlling for covariates. In a 2017 systematic review on weight and academic performance, 4 of 11 included longitudinal studies reported negative associations between obesity and academic performance in children. However, most of the studies had a high risk of bias, limiting the reviewer's conclusions ((12)). In contrast, the use of national cohort data overcomes such risk and provides stronger evidence for the negative associations observed. Our findings are also consistent with a cross-sectional study of Chinese adolescents aged 11 to 13 years that found math, Chinese, and English test scores to be higher in children with normal weight compared with children with ov/ob ((22)). Negative impacts of obesity on adolescents’ academic performance may be explained by various mechanisms, such as poor physical and mental health with subsequent absenteeism from school, impaired cognition, and impaired working memory ((22-24)). Negative impacts of obesity on standardized subject test scores appeared to be more pronounced in girls.

All adolescents with ov/ob had lower school-life experience scores as well, except for boys. Our findings were consistent with previous studies finding ov/ob to be associated with poorer school careers and social skills and decreased participation in school activities ((25, 26)). From our analyses of specific domains of school-life experience, we observed that ratings of relationships with teachers and other students, participation in school activities, and general sentiments about school were lower in adolescents with ov/ob than in adolescents without overweight. In the literature, adolescents with ov/ob often have lower self-esteem compared with normal weight peers, and adolescents with lower self-esteem generally have negative attitudes and limited capacity to respond to daily and developmental challenges. Thus, such youth are more likely to engage in negative school behaviors and/or experience negative psychological conditions at school ((27)). The finding that girls with ov/ob in particular had lower school-life experience scores could be attributed to the fact that girls with ov/ob may face more body weight–related stigmatization than boys and may also be more likely to be distressed by teasing or bullying. Teasing and bullying have been linked to less positive experiences and feelings at school ((28, 29)).

Changes in weight status between grade 7 and grade 9 affected academic performance at grade 9 in two main ways. First, all adolescents of both genders who continued to have ov/ob had consistently negative associations with standardized subject test scores. Second, all adolescents who developed ov/ob from normal weight experienced lower Chinese and math test scores and decreased school-life experience scores, except for girls. Surprisingly, some studies have found having ov/ob to be associated with lower academic achievements only for girls. For example, in the only longitudinal study of adolescents on this topic, girls in the UK who had ov/ob throughout age 11 to age 16 and girls who developed obesity at age 16 from previously having overweight had lower English test scores at age 16 compared with girls who had a healthy weight throughout; these associations were not observed among boys in the UK ((13)). Another longitudinal study among US children showed that girls who developed overweight at grade 3 after having normal weight at kindergarten had reduced academic performance. Also, having overweight throughout the time between kindergarten and third grade was associated with more internal behavior problems for girls but not for boys ((30)). Our findings support the idea that continuing to have ov/ob or developing ov/ob from normal weight during adolescence affects not only girls’ academic performance but boys’ as well. Considering 9.0% of adolescents in China had ov/ob between grade 7 and grade 9, while 8.3% developed ov/ob, our findings emphasize the critical need to prevent and treat ov/ob among Chinese adolescents.

Equally important to note is that among the 14.9% of boys and 10.4% of girls who became normal weight at grade 9 after having ov/ob at grade 7, academic performance was still lower at grade 9 compared with children who had normal weight throughout the same time period. These findings are consistent with a Taiwanese longitudinal study of senior high school students that found that students who had overweight in their first year but not third year of high school were more likely to score lower on university entrance exams compared with those who were stable at a normal weight ((31)). Several mechanisms have been advanced to explain why reduction to normal weight from having had ov/ob poses a risk factor for academic performance. Weight loss was associated with dysregulation of hormone secretion, which was, in turn, associated with lower cognitive performance ((32)). Additionally, weight loss was found to be associated with affective disturbances among high school students, which may impair students’ memory and other cognitive processes ((33)). Our findings indicate that attention should be paid to not only students who develop ov/ob between grade 7 and grade 9 but also students who may have previously had ov/ob in middle school.

The present study has some important strengths, including large sample size, cohort study design, the ability to adjust for a variety of confounders, and comprehensive characterization of academic performance that combines objectively measured core subjects test scores with self-reported school-life experience. The ability to explore distinctions in the impacts of ov/ob on academic performance and conduct using stratified analyses by gender was also very valuable. Additionally, our study provides insights of health trajectories in the new Chinese societal context, and these findings may be applicable to other rapidly developing contexts as well, particularly those in which education is similarly societally prized.

This study also has some limitations, which should be considered in the interpretation of our results. Body weight and height were self-reported and could thus suffer from errors that might weaken the observed associations. Although prevalence of obesity based on such reported measures tends to be underestimated, self-reported height and weight are widely used in population-based studies, and their values closely correlate to those measured in most cases ((34)). Second, although some potential mediators of associations between obesity and academic performance have been documented in the literature (e.g., weight stigma), we were unable to examine mediation in our study, as such data were not available. Third, we were not able to control for some potential confounders (e.g., physical fitness, physical activity), as such data were also not available ((12)). Future studies on the effects of ov/ob on academic performance may take these factors into consideration.

In conclusion, ov/ob had adverse effects on academic performance of adolescents in China. Changes in weight status between grade 7 and grade 9 were associated with academic performance at grade 9. Specifically, adolescents who continued to have ov/ob, developed ov/ob after having had a normal weight, and returned to normal weight from ov/ob had lower academic performance than those who maintained normal weight status throughout. Parents, educational professionals, and public health policy makers should additionally consider the detrimental impacts of obesity on the academic performance of adolescents in China and spearhead efforts for obesity prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We warmly thank all the dedicated and conscientious volunteers (middle school students) in the CEPS cohort. We also thank the CEPS research team for data collection and management of the CEPS database.

Funding agencies

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number U54 HD070725) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (grant number Unicef 2018-Nutrition-2.1.2.3).

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author contributions:

YFW and WDW designed the research; WDW provided essential materials; LWG, LM, and YXD performed statistical analyses; LM and DTC drafted the manuscript; LM and YFW had primary responsibility for the final content and are the guarantors; all authors critically helped in the interpretation of results, revised the manuscript, and provided relevant intellectual input; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.