Effects of high-sugar and high-fiber meals on physical activity behaviors in Latino and African American adolescents

Funding agencies: This study was supported by the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) as part of the USC Minority Health Center of Excellence (NCHMD P60 MD002254) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), NCI Centers for Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer (TREC, U54 CA 116848) as part of the USC Center for Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer. Work on this manuscript was supported by NCI to G.A.O. (T32CA009492).

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Abstract

Objective

This crossover experimental study examined the acute effects of high-sugar/low-fiber (HSLF) vs. low-sugar/high-fiber (LSHF) meals on sedentary behavior (SB) and light-plus activity (L+) in minority adolescents with overweight and obesity.

Methods

87 Latino and African American adolescents (mean age = 16.3 ± 1.2 years, mean BMI z-score = 2.02 ± 0.52, 56.8% Latino, 51.1% male) underwent two experimental meal conditions during which they consumed HSLF or LSHF meals. Physical activity and SB were measured using accelerometers, and blood glucose and insulin were collected every 30 minutes over 5 hours. Mixed models were used to examine the temporal trends of SB and L+, whether the temporal trends of SB and L+ differed by meal condition, and the influence of blood glucose and insulin on the activity behaviors.

Results

SB and L+ fluctuated over time during the HSLF condition but were stable during the LSHF condition. SB and L+ were influenced by the blood glucose response to the HSLF meals. Insulin did not influence SB or L+ in either meal condition.

Conclusions

Sugar and fiber content of meals can have differing acute impacts on activity behaviors in minority adolescents with overweight and obesity, possibly due to differing metabolic responses.

Introduction

Little is known about how consumption of sugar, a major component of the U.S. diet (1), and consumption of fiber, which is under-consumed in the U.S. diet (2), may influence physical activity and sedentary behavior (SB). Studies have indicated that diets high in simple carbohydrates may be associated with feelings of fatigue and low energy, which could negatively influence levels of physical activity and SB (3, 4). In addition, studies have found correlations between high sugar intake and low physical activity (5, 6). However, little else is known about how activity behaviors are influenced by sugar and fiber consumption.

Adolescents are one population for which elucidating this relationship may be important. Sugar consumption has risen in recent decades among U.S. adolescents (1, 7). Adolescents also tend to have diets low in fiber (1). The typical diets of African American and Latino adolescents are less healthy than the typical diets of adolescents from other ethnic groups. African American and Latino youths have dietary fiber intake from whole-grain, fruit, and vegetable sources below national dietary guidelines and sugar intake above guidelines (8, 9). Adolescents from these populations also do not meet physical activity recommendations (10). The age-related decline in physical activity that is exhibited by adolescents (11, 12) is more pronounced in Latino and African American adolescents than youths from other ethnic groups (13). Adolescence is a critical time for establishing health behaviors, as both dietary patterns and physical activity habits in this period of life track into adulthood (14, 15). It is clearly important to understand how dietary intake may influence activity behaviors in these populations.

A previous exploratory pilot study by our research group examined the influence of high-sugar and low-sugar breakfasts on physical activity in a group of 10 Latino adolescent girls with obesity (16). This preliminary in-laboratory crossover design study found overall differences in physical activity and SB between meal conditions (16), but yielded a small subject-level sample size and insufficient prompt-level data to examine temporal changes in activity behaviors. The current study aimed to expand upon the pilot study findings by extending the time period for data collection, increasing the sample size, and examining potential underlying mechanisms for differences in activity behaviors by meal condition.

This randomized crossover study investigated the metabolic and activity responses to high-sugar/low-fiber (HSLF) and low-sugar/high-fiber (LSHF) conditions. Our research aim was to examine the dynamics of SB and of light-plus activity (L+) over time in response to meals with differing dietary sugar and fiber profiles, and to determine if the metabolic responses to meals with differing dietary sugar and fiber profiles influenced activity behavior change over time. Therefore, we describe the influence of meal type on temporal changes of SB and L+ over 5 hours, whether these differed by meal condition, and the possible influence of blood glucose and insulin on the growth curves of these activity behaviors.

Based on findings from previous studies and our pilot study (16-18), we hypothesized that compared to the LSHF condition, the HSLF condition would be associated with a steeper decrease in L+ and a steeper increase in SB over the course of the in-laboratory observation period. In addition, we hypothesized that a more pronounced metabolic response to the HSLF condition would mean that blood glucose and insulin would have a greater impact on the growth curves of the activity behaviors in the HSLF condition compared to the LSHF condition.

Methods

Participant recruitment

Participants were recruited from the Los Angeles area from 2007 to 2010. The inclusion criteria were: African American or Latino ethnicity, male or female 14–17 years old, and body mass index (BMI) ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex. The exclusion criteria were: diagnosis of diabetes, participation in a weight loss or exercise program, use of medications that influenced body weight or insulin sensitivity, or diagnosis of a syndrome that influences body composition. Prior to study procedures, informed written parental consent and participant assent were obtained. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California. Participants were provided with tiered compensation ($100 for the first visit, $125 for the second visit).

Experimental design

This study used a randomized crossover design. Two experimental meal conditions were employed in a 5-hour in-laboratory setting: a HSLF condition and a LSHF condition. The HSLF and LSHF conditions were conducted during two in-laboratory visits separated by a 2- to 4-week washout period. Participants underwent both conditions and were randomly assigned to a HSLF/LSHF or a LSHF/HSLF visit order using a stratified block design randomization procedure.

Experimental meal conditions

The HSLF and LSHF meals were developed using data from focus groups conducted with a representative sample of youth. HSLF meals consisted of a Pop-Tart™ (Kellogg NA Co.), calcium-enriched string cheese (Sargento™ Mootown Light String Cheese, Sargento Foods Inc.), and Tampico juice (Tampico Beverages). LSHF meals consisted of a whole-wheat bagel, margarine (I Can't Believe It's Not Butter!™ Light, Unilever PLC/Unilever N.V.), and water treated with a soluble fiber powder (Benefiber™, Novartis Consumer Health, Inc.). Nutrient compositions were determined using the Nutrient Data System for Research (NDS-R 2010). The meals were isocaloric and matched for macronutrients; only dietary fiber and sugar contents varied. Table 1 shows the nutrient contents of each meal. Portions were approximately 20% of the participant's daily caloric need, which was calculated with the Dietary Reference Intake Guidelines Estimation of Energy Expenditure for children ages 3–18 with overweight (19). Each meal was provided for breakfast and lunch. A Registered Dietician (RD) designed the meals and prepared or supervised the preparation of all meals.

| Macronutrient g (% kcal) | HSLF meal | LSHF meal |

|---|---|---|

| 54.0 g pastry | 61.0 g whole-grain bagel | |

| 42.0 string cheese | 14.0 g margarine | |

| 247.0 g juice | 10.5 g fiber supplement | |

| Fat | 11.0 (24%) | 9.5 (24%) |

| Carbohydrate | 64.0 (61%) | 61.0 (68%) |

| Protein | 14.0 (13%) | 10.0 (11%) |

| Sugar | 41.0 (39%) | 7.0 (8%) |

| Fiber | 1.0 (1%) | 16.0 (18%) |

- HSLF: high-sugar/low-fiber meal condition; LSHF: low-sugar/high-fiber meal condition; kcal: kilocalories; g: grams.

Demographic and baseline measures

Data was collected from 2008 to 2010. Potential participants attended a screening exam at the Clinical Trials Unit at the USC University Hospital. Eligible participants completed an inpatient visit where insulin sensitivity, body weight, height, and demographic data were collected. Height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured in triplicate by a Registered Nurse. BMI percentile was calculated based on the CDC age- and sex- specific growth charts (20).

Insulin Sensitivity (SI) was assessed at a baseline visit via 3-hour Frequently Sampled Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (FSIVGTT) (21). Blood samples were collected at −15, −5, 2, 4, 8, 19, 22, 30, 40, 50 70, 100, and 180 minutes. Glucose (25% dextrose, 0.3 g/kg body weight) was administered intravenously at time 0 and insulin [0.02 units/kg body weight, Humulin R regular insulin for human injection; Eli Lilly] at 20 minutes. SI was calculated using the minimal model from the FSIVGTT results (22) [MINMOD MILLENIUM 2002 computer program, Version 5.16; Richard Bergman, Los Angeles, CA (23)].

In-laboratory procedures

Participants began each visit after a 10-hour overnight fast. A saline lock intravenous catheter was placed into the forearm for blood sampling. Participants were given 15 minutes to complete the meal, then instructed to choose from activities available in the laboratory for the observation period. Options were based on feedback from the aforementioned focus groups. Active options included Nintendo Wii, treadmill, small trampoline, jump rope, hula-hoops, free weights, Rock Band, and Dance Dance Revolution. Sedentary options included books, movies, arts and crafts center, listening to music, and movies.

In-laboratory activity behavior measures

Activity behaviors were assessed via accelerometry. Participants wore a uniaxial Actigraph GT1M accelerometer on the right hip using an elastic belt during each visit. The accelerometer collected activity data in 60-second epochs. Accelerometer data was processed using SAS code developed by the National Cancer Institute for use with NHANES data (http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/tools/nhanes_pam). Time spent in activity levels was calculated by summing each minute spent below the cut point for SB and above the cut points for light physical activity and moderate to vigorous physical activity. A previously defined and validated cut point of 100 counts per minute was used to define SB (24). The thresholds for light-intensity physical activity (<4 METs) and moderate- or greater intensity physical activity (4+ METs) were age-adjusted using the criteria from Freedson and colleagues (25). Time spent in each activity category was calculated by summing the minutes of counts above or below the appropriate threshold. Minutes in each activity category were summed for each 30-minute interval over 5 hours. Due to a very low amount of moderate to vigorous physical activity in this sample, the minutes of light and moderate to vigorous physical activity data were summed to create a “light-plus activity (L+)” variable.

In-laboratory metabolic measures

Blood samples were taken at −5 minutes prior to the first meal and every 30 minutes after for a total of 5 hours during each visit. Samples were centrifuged in a microfuge on-site within 1 hour of blood draw, placed on ice, and transported on dry ice to the on-site laboratory where they were stored at −70 C until assayed. Blood glucose was analyzed on a Dimension Clinical Chemistry system and an in vitro Hexokinase method (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL). Insulin was assayed with an automated random access enzyme immunoassay system Tosoh AIA 600 II analyzer (Gibbco Scientific, In. Coon Rapids, MN) using an immunoenzymometric assay (IEMA) method.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Significance levels for statistical tests were set at α = 0.05. Data were analyzed using repeated measures analyses via PROC MIXED with an approach similar to dyadic multilevel modeling (26). This approach was used because the design of the study led to interdependence of outcome measures in each condition within each participant, analogous to the interdependence of actor and partner data in a dyadic study. The dyadic multilevel modeling approach expands standard multilevel modeling by accounting for statistical dependency of data between paired observations (or in this case, between conditions), as well as statistical dependency of data within individuals (27, 28). This approach also yielded simultaneous estimation of growth curves for activity behaviors in each condition separately (26, 28). In order to conduct this type of multilevel analysis, the data was structured so that the meal condition variable was separated into two dichotomous variables, one to indicate the HSLF condition (1 = HSLF, 0 = LSHF) and the other to indicate the LSHF condition (1 = LSHF, 0 = HSLF) (26, 29, 30). SB and L+ outcomes were non-normally distributed. A square transformation was used on SB and square root transformation was used on L+ (31, 32).

First, the ideal functional form (i.e., effect of time) describing the change of SB and L+ over the in-laboratory observation periods was identified. This approach involved modeling the growth curves for the outcome with time and its higher-order function (without including covariates) for each condition separately in order to find the best fitting functional forms for the change in activity behavior outcomes over time.

Second, multilevel models were run to determine (1) if the growth curves of the activity behavior outcomes differed between condition, and (2) if these growth curves were influenced by blood glucose or insulin measures. To determine whether the growth curves differed by condition, meal condition by time interactions were included in the models. An interaction term for metabolic measure (blood glucose or insulin) by time by meal condition was included in the models to examine the influence of metabolic measures on the activity behavior outcomes. A separate model tested for each activity behavior outcome and for each metabolic predictor for a total of four models (the influence of blood glucose on the SB growth curve, the influence of insulin on the SB growth curve, the influence of blood glucose on the L+ growth curve, and the influence of insulin on the L+ growth curve).

Blood glucose and insulin were time-varying predictors that varied both between- and within-person. To differentiate the effects of the between- and within-person variance of the metabolic measures on the activity behavior outcomes, the metabolic variables were disaggregated into their respective between- and within-person effects (33). These between- and within-person effects were included as separate variables in each model. A priori time-invariant covariates included age, sex, ethnicity, BMI z-score, baseline insulin sensitivity, and randomization order.

For all models, the variance components were estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation method. A Kronecker product structure was specified for the residuals. Random effects were included for the intercepts of both the HSLF and LSHF conditions. A no intercept (“NOINT”) option was included in the model statements to suppress the intercept for the aggregate data and allow the estimation of the intercepts for each condition separately (27, 34). Post-hoc contrast statements were added in all models to empirically test whether the estimates for the intercepts and growth curves for each activity behavior outcome differed by condition. Estimates from the model results were used to plot the functional forms of the activity behaviors over time.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Baseline sample characteristics are displayed in Table 2. A total of 87 participants were included in the study (56.8% Latino, 51.1% male). There was no participant attrition between visits. The mean age of the participants was 16.3 ± 1.2 years and the mean BMI z-score was 2.02 ± 0.52. All participants had overweight or obesity (77.3% had obesity). Preliminary analysis of the growth curves for SB and L+ revealed that a cubic functional form was optimal for describing the change in both SB and L+ over the course of the observation periods. Results from the multilevel models are shown in Tables 3 and 4. The general level 1 and level 2 equations for the analyses are shown in Table 5.

| Variable | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 16.3 (1.2) |

| BMI z-score | 2.02 (0.52) |

| Weight status | |

| Overweight | 5.7% (5) |

| Obese | 94.3% (83) |

| Insulin sensitivity (SI) | 1.6 (1.1) |

| Sexa | |

| Male | 48.9% (43) |

| Ethnicitya | |

| African American | 43.2% (38) |

| Latino | 56.8% (50) |

- Mean and (SD) reported, unless otherwise indicated.

- a Frequencies (N).

- SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index.

| HSLF condition, | LSHF condition, | Comparison of HSLF vs. LSHF estimates, | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B (SE) | B (SE) | t-valuec |

| Sedentary behaviorb | |||

| Intercept | 1046.23 (148.43)*** | 820.43 (114.48)*** | 1.53 |

| Meal × time | −164.40 (64.26)* | −6.70 (51.99) | −1.92 |

| Meal × time2 | 23.83 (8.72)** | −0.41 (7.38) | 2.13* |

| Meal × time3 | −1.05 (0.37)** | 0.05 (0.32) | −2.24* |

| Meal × blood glucosebs | 0.91 (1.25) | 0.52 (1.27) | 0.28 |

| Meal × blood glucosews | −12.84 (5.76)* | −6.73 (8.05) | −0.62 |

| Meal × time × blood glucosews | 6.67 (2.90)* | 3.43 (3.94) | 0.67 |

| Meal × time2 × blood glucosews | −0.99 (0.43)* | −0.51 (0.57) | −0.67 |

| Meal × time3 × blood glucosews | 0.05 (0.02)* | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.67 |

| Light-plus activityd | |||

| Intercept | 0.18 (0.74) | 1.07 (0.57) | 1.32 |

| Meal × time | 0.74 (0.32)* | 0.03 (0.26) | 1.73 |

| Meal × time2 | −0.11 (0.43)* | 0.004 (0.04) | −1.96 |

| Meal × time3 | 0.005 (0.002)* | −0.004 (0.002) | 2.09* |

| Meal × blood glucosebs | −0.005 (0.007) | −0.003 (0.01) | −0.26 |

| Meal × blood glucosews | 0.06 (0.03)* | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.62 |

| Meal × time × blood glucosews | −0.33 (0.01)* | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.64 |

| Meal × time2 × blood glucosews | 0.005 (0.002)* | 0.003 (0.003) | −0.62 |

| Meal × time3 × blood glucosews | −0.0002 (0.0001)* | −0.0001 (0.0001) | |

| 0.62 | |||

- a Models control for age, ethnicity, baseline insulin sensitivity, sex, BMI z-score, and randomization order (estimates not reported).

- b Estimates for square transformed sedentary behavior.

- c t-value from contrast tests comparing estimates between HSLF and LSHF meal conditions.

- d Estimates for square root transformed light-plus activity.

- *P < 0.05.

- **P < 0.001.

- ***P < 0.0001.

- SE = standard error; meal = meal condition variable (HSLF or LSHF); HSLF = high-sugar meal condition; LSHF = high-fiber meal condition; blood glucosebs: between-subject blood glucose; blood glucosews: within-subject blood glucose; time2: quadratic time trend; time3: cubic time trend.

| Variable | HSLF condition, B (SE) | LSHF condition, B (SE) | Comparison of HSLF vs. LSHF estimates, t-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary behaviorb | |||

| Intercept | 987.37 (135.48)*** | 826.57 (101.98)*** | 1.30 |

| Meal × time | −157.12 (59.74)** | −19.24 (47.82) | −1.81 |

| Meal × time2 | 24.47 (8.23)** | 2.05 (6.94) | 2.09* |

| Meal × time3 | −0.08 (0.31) | −0.12 (0.14) | −2.25* |

| Meal × insulinbs | −0.12 (0.14) | −0.15 (0.14) | 0.23 |

| Meal × insulinws | −2.95 (1.18)* | −3.11 (1.59) | 0.08 |

| Meal × time × insulinws | 1.66 (0.58)** | 1.75 (0.79)* | −0.08 |

| Meal × time2 × insulinws | −0.25 (0.09)** | −0.27 (0.12)* | 0.15 |

| Meal × time3 × insulinws | 0.01 (0.004)** | 0.01 (0.01)* | 0.15 |

| Light-plus activityd | |||

| Intercept | 0.53 (0.68) | 0.99 (0.51) | −0.95 |

| Meal × time | 0.67 (0.30)* | 0.11 (0.24) | 1.48 |

| Meal × time2 | −0.11 (0.04)* | −0.01 (0.03) | −1.78 |

| Meal × time3 | 0.005 (0.002)** | 0.0003 (0.002) | 1.95 |

| Meal × insulinbs | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | −0.34 |

| Meal × insulinws | 0.01 (0.01)* | 0.02 (0.01)* | −0.25 |

| Meal × time × insulinws | −0.01 (0.003)* | −0.01 (0.004)* | 0.28 |

| Meal × time2 × insulinws | 0.001 (0.0004)** | 0.001 (0.001)* | −0.37 |

| Meal × time3 × insulinws | −0.00001 (0.00002)* | −0.0002 (0.00003)* | −0.37 |

- a Models control for age, ethnicity, baseline insulin sensitivity, sex, BMI z-score, and randomization order (estimates not reported).

- b Estimates for square transformed sedentary behavior.

- c t-value from contrast tests comparing estimates between HSLF and LSHF meal conditions.

- d Estimates for square root transformed light-plus activity.

- *P < 0.05.

- **P < 0.001.

- ***P < 0.0001.

- SE = standard error; meal = meal condition variable (HSLF or LSHF); HSLF = high-sugar meal condition; LSHF = high-fiber meal condition; blood glucosebs: between-subject blood glucose; blood glucosews: within-subject blood glucose; time2: quadratic time trend; time3: cubic time trend.

| Level 1: |

| Yij = π0i HSLFij + π1i HSLFij + π2i HSLFij × Timeij + π3i LSHFij × Timeij + π4i HSLFij × Time2ij + π5i LSHFij × Time2ij + π6i HSLFij × Time3ij + π7i LSHFij × Time3ij + π8i HSLFij × Metabolicwsij + π9i LSHFij × Metabolicwsij + π10i HSLFij × Timeij × Metabolicwsij + π11i LSHFij × Timeij × Metabolicwsij + π12i HSLFij × Time2ij × Metabolicwsij + π13i LSHFij × Time2ij × Metabolicwsij + π14i HSLFij × Timeij3 × Metabolicwsij + π15i LSHFij × Timeij3 × Metabolicwsij + εij |

| Level 2: |

| π0i = γ00 + γ01Metabolicbsi + γ02Ethnicityi + γ03Sexi + γ04BMI-zi + γ05Agei + γ06SIi + γ07Randomizationi + ζ0j |

| π1i = γ10 + γ11Metabolicbsi + γ12Ethnicityi + γ13Sexi + γ14BMI-zi + γ15Agei + γ16SIi + γ17Randomizationi + ζ1j |

| Where: Yij = sedentary behavior or light-plus activity; HSLF = high sugar/low fiber meal condition; LFHF = low sugar/high fiber meal; Metabolicws = within-subject effect of blood glucose or insulin; Metabolicbsi = between-subject effect of blood glucose or insulin; BMI-z = body mass index z-score; SI = baseline insulin sensitivity; Randomization = randomization order |

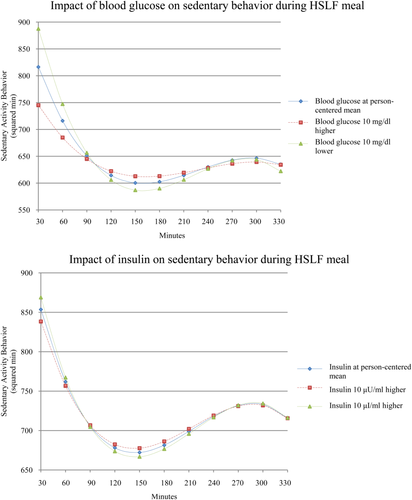

Effect of blood glucose and insulin on the growth curves of SB

In the HSLF meal, there were significant linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time on SB (Table 3 first column and Table 4 first column). This indicated that SB initially decreased, then increased, and subsequently decreased again over the course of the day during the HSLF condition. There were no significant fluctuations of SB when participants were in the LSHF condition (Table 3 second column and Table 4 second column).

In the HSLF condition, the effects of blood glucose on SB varied as a function of time (Table 3 first column). Figure 1 shows the cubic functional form of SB during the HSLF condition for when blood glucose was at one's mean level (centered at overall person mean), as well as when blood glucose was higher and lower than one's mean level. In the HSLF condition, higher than mean blood glucose was initially associated with lower SB, and lower than mean blood glucose was initially associated with higher SB. Between 90 minutes post-breakfast and the start of lunch at 240 minutes, higher than mean blood glucose was associated with higher SB and lower than mean blood glucose was associated with lower SB. After 240 minutes, higher blood glucose was again associated with lower SB and lower blood glucose was again associated with higher SB. Insulin did not impact SB during the HSLF condition.

Influence of blood glucosea and insulinb on SB during HSLF meal condition. (a) Higher blood glucose than usual was initially associated with lower SB, and lower blood glucose than usual was initially associated with higher SB. Between 90 minutes after breakfast and lunch (at 240 minutes), higher blood glucose was associated with higher SB, and lower blood glucose was associated with lower SB. After lunch, higher blood glucose was again associated with lower SB, and lower blood glucose was again associated with higher SB. (b) Insulin did not impact SB. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

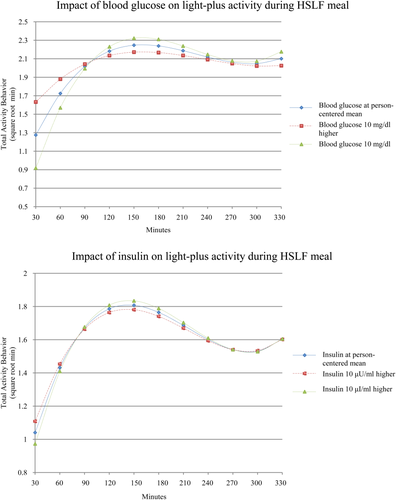

Effect of blood glucose and insulin on the growth curves of L+ activity

In the HSLF condition, there were significant linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time on L+ (Tables 3 first column and Table 4 first column). This indicated that L+ initially increased, then decreased, and subsequently increased again over the course of the day during the HSLF condition. There were no significant fluctuations of L+ when participants were in the LSHF condition (Table 3 second column and Table 4 second column).

In the HSLF condition, the effects of blood glucose on L+ varied as a function of time (Table 3 first column). Figure 2 shows the cubic functional form of L+ during the HSLF condition for when blood glucose was at one's mean level, as well as when blood glucose was higher and lower than one's mean level. In the HSLF condition, higher than mean blood glucose was associated with higher L+ during the first 90 minutes, and lower than mean blood glucose was associated with lower L+ during the first 90 minutes. After 90 minutes post-breakfast, higher than mean blood glucose was associated with lower L+, and lower than mean blood glucose was associated with higher L+. Insulin did not impact L+ during the HSLF condition.

Influence of blood glucosea and insulinb on light-plus activity during HSLF meal condition. (a) Higher blood glucose than usual was initially associated with higher light-plus activity, and lower blood glucose than usual was initially associated with lower light-plus activity. After 90 minutes post-breakfast, higher than usual blood glucose was associated with lower light-plus activity, and lower than usual blood glucose was associated with higher light-plus activity. (b) Insulin did not impact light-plus activity. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the acute effects of two meal conditions that differed in sugar and fiber content on temporal trends of SB and light-plus activity, and to determine if metabolic responses to these meals influenced activity behaviors. We found that meal type and blood glucose influenced activity in the HSLF condition only. SB and light-plus activity appeared to change subsequent to meal consumption in the HSLF condition. Consumption of simple carbohydrates during the HSLF condition after an overnight fast could have temporarily lead to a relief in feelings of fatigue or may have relieved depletion of skeletal muscle energy, which could have influenced activity behaviors (35). This response could have occurred again after the HSLF lunch meal. While this explanation provides possible support for our findings, studies examining the influence of dietary sugar content on SB and physical activity over the long-term are needed to elucidate the broader impact of high-sugar diets on activity behaviors.

Another potential explanation for our findings is that an acute decrease in SB and increase in light-plus activity in response to a high-sugar meal could represent a compensatory response by the body to regulate blood glucose levels. Individuals with overweight and obesity tend to have blunted insulin responses, which result in high blood glucose levels in response to high-sugar foods (36). Skeletal muscle activity aids in uptake of blood glucose from the bloodstream (37), so increasing activity may be a way in which the body compensates to regulate glucose levels after consumption of high amounts of sugar in individuals with overweight. This may provide support to the influence of blood glucose on the functional forms of SB and light-plus activity levels we found in the HSLF condition. Neuronal control of energy balance may provide another explanation for our findings. Orexin neurons in the brain are glucose sensing, and the neurotransmitter orexin A has the ability to induce spontaneous physical activity (38, 39). Enhanced orexin signaling prompted by the sensing of glucose by orexin neurons may induce activity to maintain short-term energy balance (38). This may be another potential mechanism for the influence of the HSLF condition on SB and light-plus activity.

The LSHF condition findings may also be supported by the notion of a compensatory response to a high-sugar meal. Perhaps such a compensatory response using physical activity to regulate blood glucose levels would not have been necessary in the LSHF condition. Fiber intake stabilizes blood sugar and insulin concentrations (40). Therefore, there may be less of a compensatory response to regulate blood glucose levels after consumption of LSHF meals. This may explain why there was a lack of change in participant activity behaviors throughout the day in the LSHF condition.

This study has several strengths. The controlled environment of the in-laboratory visits allowed for objective measurement of food intake and observation of activity behaviors, and allowed us to determine the temporal relationship between food consumption and the influence on activity behaviors. Since this study used a crossover design, we were able to compare the influences of both HSLF and LSHF meal consumption on activity behaviors in the same participants. Focus groups of Latino and African American participants were used to determine the foods included in the test meals, so the meals represented breakfast foods that were typical of these populations. The focus groups were also used to determine the in-laboratory activity options, so both the active and sedentary options reflected activities that are typically enjoyed by this demographic.

This study also has limitations that should be noted. While the in-laboratory crossover design was a strength, it may have limited the generalizability of the findings to free-living situations. Habitual dietary intake may play an important role in influencing activity behavior, and a short-term feeding study may not be sensitive enough to demonstrate larger variations in activity potentially influenced by dietary intake. Participants were aware that they were being observed in the lab setting, which could have influenced the activities they chose. It is possible that participants could have figured out the purpose of the study since they were required to consume different types of foods and subsequently be observed in the lab setting. The models for both SB and light-plus activity did not allow the time terms to vary randomly because the models would not converge with inclusion of these terms in the random effects statements.

Conclusion

This is the first study to our knowledge to demonstrate that high-sugar/low-fiber foods can acutely influence activity behaviors in minority adolescents. Future research should aim to elucidate the longer-term influence of sugar and dietary fiber on activity behaviors as well as the influence of dietary intake on activity in free-living settings. Findings from this study and future studies may have implications for multiple behavior weight loss interventions aimed at reducing sugar intake and SB and increasing fiber intake and physical activity.