The Zooarchaeology of an Iberian Medieval Jewish Community: The Castle of Lorca (Murcia, Spain)

Funding: This research was developed thanks to the Project “Los judíos del Reino de Murcia durante la Baja Edad Media: cultura material, documentos y memoria” (21864/PI/22), funded by Fundación Séneca (Agencia Regional de Ciencia y Tecnología, CARM), and it is framed within the Synergy Project MEDGREENREV funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's HORIZON ERC programme (Grant agreement No. 101071726).

ABSTRACT

Archaeological excavations at the castle of Lorca (Murcia, Spain) led to the identification of part of the Jewish district of the town. This area, occupied between the 14th and 15th centuries, represents a unique example of a medieval frontier Jewish quarter defined by complex urban planning, a synagogue, and various domestic units. Archaeological work allowed the recovery of a large number of animal remains. This paper deals with the results of the zooarchaeological study of this archaeofaunal assemblage, aiming to shed light on the ways in which animals were exploited, distributed, prepared and consumed by medieval Jewish population of Lorca. The results reveal a model of animal economy centered on the exploitation of caprines (sheep/goat) and, to a lesser extent, cattle, chickens and other secondary species, although the presence of non-kosher species such as pigs and rabbit is noteworthy. The identification of butchery marks attributed to the porging of the hindquarters of caprines, a practice typical of medieval Jewish communities, represents a marker of ethno-religious identity of great historical interest.

1 Introduction

In recent years, studies that attempt to characterize medieval Iberian populations through zooarchaeological indicators have been multiplying. In this short paper, we present the first results of the studies on the faunal remains carried out in Lorca castle (Murcia), a medieval fortified settlement in the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula that was inhabited by Jewish populations in the 14th and 15th centuries. Comparative analysis has allowed us to define significant food practices of this Jewish population. Taking into account the traditional absence of archaeological indicators in this sense, we consider that they could be relevant to be used in other similar sites. With this objective in mind, firstly, a historical and archaeological approach to the context in which the remains analyzed were found is given; secondly, the materials and methods of analysis used are presented; and thirdly, the first results are summarized, which allow us to broadly define the production, distribution, processing, and consumption patterns of animal products by the Jewish population that inhabited this site.

2 Historical and Archaeological Context: The Jewish Quarter of Lorca

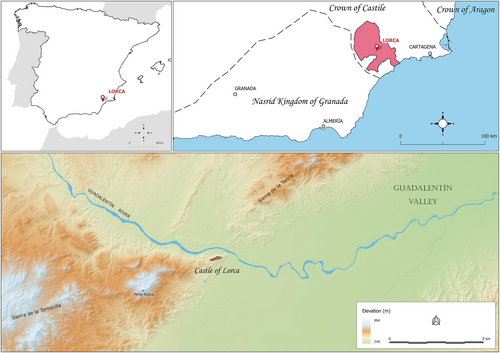

The castle of Lorca is located in the southeast of Spain, dominating the entire Guadalentín Valley in the region of Murcia (Figure 1). Its location was decisive during the Islamic period (713–1243), as a control point of the two main routes connecting the Valencian region and the south of the Peninsula, and in the geopolitical context of the Late Middle Ages it acquired a special relevance, becoming the last bastion of the Kingdom of Castile against the Nasrid kingdom of Granada in that border sector (Jiménez 1997), which remained almost unchanged for more than two centuries (1243–1492).

The incorporation of the Kingdom of Murcia into the Crown of Castile in 1244 produced important modifications to the fortified enclosure, which in the Andalusi period had been the citadel of the urban center. After the conquest, the Castilian population settled in a sector of the eastern part of the castle that began to be known as the barrio de Alcalá, a well-defined and individualized space, which was accessed from the city through the Puerta del Pescado, an angled entrance located in one of the towers of the wall.

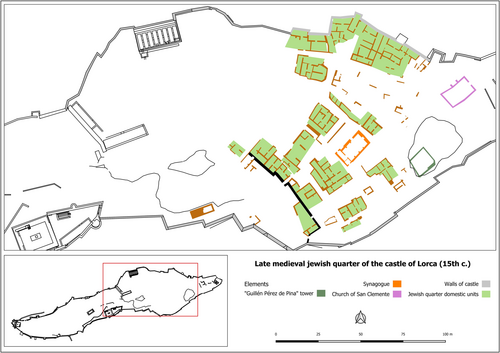

The barrio de Alcalá was the place where the Jewish quarter gradually took shape throughout the 14th century (Figure 2). Although some indications from Arab sources suggest that the Jewish presence in Lorca was relevant before the Christian conquest, it seems that it acquired real importance after the Christian conquest and in the following century, until it became a majority in the mid-15th century (as suggested by the appointment of the Jew José Rufo as the person in charge of the maintenance of the fortress on behalf of Alonso Fajardo) (Veas 1992). The craft, commercial and above all, livestock activity of some members of the Jewish community in the context of the Murcian–Granadine border must have provided this minority with an advantageous economic situation and a high degree of integration in the local socioeconomy; and their houses, workshops, and religious buildings were erected in the terraced eastern space of the castle. However, after the expulsion decree of 1492, this whole area became a marked place, with negative connotations, which was never inhabited again, ensuring the archaeological preservation of the Jewish quarter, which had already been converted into a depopulated area. The Christian population settlement was located beyond the castle, on the banks of the river Guadalentín. After its abandonment, from the 16th century to the present day, the entire sector of the Jewish neighborhood of the castle has remained uninhabited without subsequent occupation and without significant stratigraphic alterations, thus ensuring the preservation of the late medieval archaeological contexts in optimal conditions.

Although the castle of Lorca has been the subject of archaeological excavations for 50 years, it was the interventions carried out in 2003, on the occasion of the construction of the Parador Nacional de Turismo, which brought to light a complex urban network (with gateways, streets, and passageways) in which more than a dozen dwellings were defined (Gallardo and González 2009) and a monumental building that was identified with the synagogue, which has become the best Iberian example of this type of religious building that has not been converted into a church (Eiroa, Gallardo, and González 2017).

The need to systematize and interpret all the information recovered in the different interventions carried out at the site by different teams led to the creation of a long-term interdisciplinary project at the University of Murcia (Eiroa 2012), which aims to study and preserve the sector that remains intact in the castle of Lorca.1 The archaeological excavations carried out there since 2009 have brought to light the Jewish quarter established inside it in the 14th and 15th centuries, in which a craft production area and a whole series of domestic spaces stand out. After a few years of interruption, archaeological work was resumed in 2021, with the excavation of a new sector of the Jewish quarter, giving continuity to the research carried out so far (Eiroa et al. 2021).

The research in the Jewish quarter of Lorca castle allows us to raise some questions regarding the problems of identification presented by the archaeological record of the Jewish minority, which constitute the most relevant conclusions reached by the project to date. The Jewish population, which theoretically settled in legally and physically differentiated spaces, with specific urban areas (especially with the different regulations activated in the Crown of Aragon and Castile after the events of 1391) is not easily identifiable in a specific urban space without resorting to information from written documentation. Only by resorting to data from texts do we seem to be able to identify the place occupied by the Jews in a city, as there do not seem to be any differentiating material features. From a purely archaeological perspective, the Jewish communities appear to us as a minority whose identity has been materially diluted in the society in which it is embedded.

In the 18 15th-century houses found in the late medieval Jewish quarter of the castle of Lorca (of great morphological variability in plan and size), the characteristics are identical to those of the Christian settlers in the same chronological and geographical context, like those excavated in the city of Lorca itself, without any structural or organizational particularity that would allow them to be linked to the Jewish population: domestic units of simple configuration, with three or four rooms per dwelling, arranged without centralized or axial organization and with a rectangular tendency; with generally rectangular rooms, with raised alcoves and benches attached with easily identifiable kitchens, in which large jars embedded in the floor and alacenas are common; and with courtyards that, when they exist, are neither decisive nor central.

The domestic structures seem to behave like their occupants: integrating and inserting themselves into the majority dynamics. If the historical analyses carried out as part of the project have made one thing clear, it is that the Jews who inhabited the castle in the late medieval period should not be interpreted as individuals dedicated exclusively to the commercial, mercantile, or proto-banking business, as the absurd microcosmic accounts tend to interpret them, but as a population group fully integrated into the complex and dynamic society of the Castilian–Nasride frontier, which not only held those positions for which they were considered especially useful due to their knowledge of languages and their great capacity for mobility (alfaqueques, translators, interpreters, or ejeas) but also carried out an intense economic activity based on livestock (possibly taking advantage of their apparent social marginality and their geographical situation), which ensured them an important socioeconomic position (Jiménez and Martínez 2011).

There are, therefore, no clear differentiating elements that would allow us to clearly situate the presence of Jewish settlers in a dwelling, in a block of houses, or in a neighborhood on the basis of an archaeological analysis of their remains. It is not even possible to find specific features in nondomestic spaces, such as butcher's shops: The so-called house IX of the Jewish quarter of the castle of Lorca was later identified as a building with facilities for butchering, preparing, and selling meat, which had an individualized space (with pasture beds and a cobbled floor) dedicated to the care and breeding of animals; however, despite being a butcher's shop possibly associated with specific culinary activities, nothing about it seems to differ from other examples of late medieval butcher's shops (Gallardo and González 2009, 175–181).

However, the archaeological experience developed in the Jewish quarter of the castle of Lorca has revealed that there are two possibilities for identifying Jewish populations based on the detailed analysis of the archaeological contexts. On the one hand, we refer to the presence, in medieval archaeological contexts of a domestic nature, of multiple ceramic lamps associated with the celebration of Hanukkah, the so-called ‘Feast of Lights’, that seems to be a key element in the identification of the Jewish population (Eiroa 2016).

On the other hand, the zooarchaeological remains, the focus of the present study. Testimonies from other late medieval peninsular Jewish communities and some textual evidence seem to suggest that the Jews of Lorca must have complied with the dietary prescriptions of the kashrut (based, inter alia, on the precepts of Leviticus and Deuteronomy), which defined a strict diet based on pure (kosher) foods. Specifically, a 15th-century document from the Archivo Municipal of Murcia explains how several Jews from Lorca on their way to Hellín (Albacete) are stopped in Cieza (Murcia) and are involved in a fight for refusing to eat impure food: The text explicitly mentions that “e davales carne e ellos dixeron que no querían sino granadas e uvas”.2

3 Materials and Methods

The material under study comes from three distinct archaeological contexts and corresponds to the three archaeofaunal samples examined (Figure 3). Sample LOC-1 was recovered from the levels associated with the domestic unit known as House 7, located next to the synagogue and, thus, in a central area of the Jewish quarter. Sample LOC-2 comes from Sector 33 of House 16, identified as a stable. Finally, sample LOC-3 comes from the contents of a large jar excavated in Space 1 of House 14, in the northern fringe of the enclosure.

The methodology and techniques of zooarchaeology analyses employed are explained in detail in García (2019). In short, most of the material was collected manually during the excavation. Only in the most recent excavation carried out in 2020 and focused on House 16 was a protocol for the collection and flotation of bioarchaeological material applied. However, the animal remains recovered by this method were excluded from this paper to allow comparisons between the different samples. All remains were divided into two main groups: identified remains (NISP) and nonidentified remains. The first category includes remains that can be regarded as accountable based on an adaptation of Davis' (1992) protocols, being the main quantitative measure used as the baseline for calculating the remaining analytical parameters, although detailed analysis was only possible for caprines. Nonidentified fragments mostly belong to skull bones, nonidentifiable long bones (chiefly the central diaphysis), flat bones such as the scapula (except the glenoid cavity/neck) and the pelvis (except the acetabulum), vertebrae (except the atlas and the axis), ribs, and bone splinters. The differentiation between sheep and goats was only attempted for a restricted set of anatomical elements following the criteria proposed and/or summarized by Boessneck (1969), Prummel and Frisch (1986), and Zeder and Lapham (2010) for postcranial bones and Payne (1985), Halstead, Collins, and Isaakidou (2002) and Zeder and Pilaar (2010) for mandibular teeth. The age at death was estimated by examining the fusion of long bones and the mandibular eruption and wear stage. Only epiphyses with fully formed spiculae along the surface of the epiphysis were regarded as fused, and the categories obtained were quantified following O'Connor (1989) and Silver (1969). The wear stage for all P4s, dP4s, and molars, both isolated and in mandibles, was recorded following Payne (Payne 1987, 1973). Those mandibles with at least two teeth in the dP4/P4-M3 row were assigned to mandibular wear stages of Payne (1973). The quantification of bones belonging to different body parts was carried out following O'Connor (2000, 2003), with the modifications presented in García (2019), which enabled completion of an arithmetically objective quantification of significantly under- and overrepresented body parts. The analysis of anatomical representation was thus based on two methods of quantification: the minimum number of elements (MNE), defined as the minimum number of skeletal elements necessary to account for an assemblage of specimens of a particular skeletal element, part, or portion (Lyman 2008, 2020), and which was calculated using the diagnostic zones (sensu Dobney and Rielly 1988) for each major element, and the minimum anatomical units (MAU), obtained by dividing MNE values for each element or anatomical part by the number of times that element or part occurs in one complete skeleton (Binford 1984, 50). Subsequently, the MAU count for each element was further modified by dividing it by the mean of MAU counts (MAU/E). Finally, MAU/E values were rescaled to zero mean and unit standard deviation, allowing the identification of those skeletal parts that lie more than one standard deviation above or below the mean, which always equals one (O'Connor 2003, 144–147). Butchery marks were carefully recorded, counted, and marked on the templates published by Popkin (2005). Their basic features, position on the bone, and possible aim were also recorded (Binford 1981).

4 Results

The assemblage comprises 1103 fragments, 762 (69%) of which could be identified to species (NISP). This ratio of identified versus unidentified remains reveals a good identification rate, derived from a low level of fragmentation of the material examined and a good overall state of preservation.

In fact, most of the bones had little or no cortical surface alteration (76%), and only 5% had gnawing marks from commensal animals, most of them belonging to carnivores (probably dogs), whereas only a small proportion (n = 2) were attributed to rodents. The occurrence of burning marks on bones is extremely low (1%). The characteristics of these marks and their location do not allow them to be related to the practice of roasting meat, but rather to the occasional burning of food waste.

Regarding the spatial distribution among the samples, the majority of the remains comes from sample LOC-1 from House 7 (NISP = 416; 55%); 31% of the assemblage (NISP = 235) comes from LOC-2, derived from Sector 33 of House 16; and the remaining 15% (NISP = 111) was recovered from the interior of the jar excavated in House 16.

Table 1 shows the taxonomic composition of the assemblage. Caprines (sheep Ovis aries and goats Capra hircus) are the most represented taxonomic group (81% NISP). The sheep:goat ratio varies significantly between samples and favors the former species in samples LOC-1 (2:1) and LOC-2 (8:1), whereas caprine remains in sample LOC-3 were entirely attributed to goat. Caprines are followed in order of abundance by chicken (Gallus gallus dom.), then cattle (Bos taurus), rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), and pig (Sus dom.). Among the species less represented in quantitative terms are equids (Equus sp.), rats (Rattus sp.), red deer (Cervus elaphus), pigeon (Columba sp.), partridge (Alectoris rufa) and tuna (Thunnus sp.).

| Group | Taxa | LOC-1 | LOC-2 | LOC-3 | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NISP | % | NISP | % | NISP | % | NISP | % | |||

| Mammals | Livestock | Sheep (Ovis aries) | 69 | 17 | 24 | 10 | 93 | 12 | ||

| Goat (Capra hircus) | 35 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 63 | 57 | 101 | 13 | ||

| Sheep/goat (Ovis/Capra) | 253 | 61 | 130 | 55 | 42 | 38 | 425 | 56 | ||

| Caprines (Ovis + Capra + O/C) | (357) | (86) | (157) | (67) | (105) | (95) | (619) | (81) | ||

| Cattle (Bos taurus) | 27 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 33 | 4 | ||||

| Pig (Sus sp.) | 10 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 18 | 2 | ||||

| Equids (Equus sp.) | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Total livestock | (394) | (95) | (173) | (74) | (105) | (95) | (672) | (88) | ||

| Wild | Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) | 2 | 19 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 3 | ||

| Red deer (Cervus elaphus) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| Rat (Rattus sp.) | 6 | 3 | 6 | 1 | ||||||

| Birds | Domestic | Chicken (Gallus dom.) | 16 | 4 | 27 | 11 | 3 | 3 | 46 | 6 |

| Pigeon (Columba sp.) | 2 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 1 | |||||

| Wild | Partridge (Alectoris rufa) | 3 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| Fish | Tuna (Thunnus sp.) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Total | 416 | 235 | 111 | 762 | ||||||

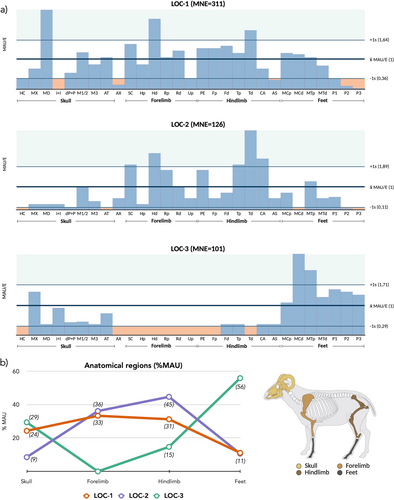

Sheep and goats are the only species sufficiently represented to allow detailed analysis of anatomical representation, for which sheep, goat, and nondetermined Caprinae remains were considered jointly. As illustrated in Figure 4, the frequency of skeletal part of caprines differs significantly between contexts. Samples LOC-1 and LOC-2 show little differences among them, with the lower proportion of skull and foot elements in LOC-2 being the most noticeable. In spite of the taphonomic bias, due to the destruction of the less dense bones, the skeletal profiles for both samples suggest the presence of complete or semicomplete carcasses (particularly in LOC-1), as well as the relatively equal frequency of elements from the forelimb (scapula, humerus, and radius) and the hindlimb (pelvis, femur, and tibia). This contrasts with sample LOC-3, where the dominant feature is the high frequency of skull and, above all, foot elements (metapodials and phalanges), which indicates that the contents of the jar identified in House 14 cannot be interpreted as kitchen or table refuse.

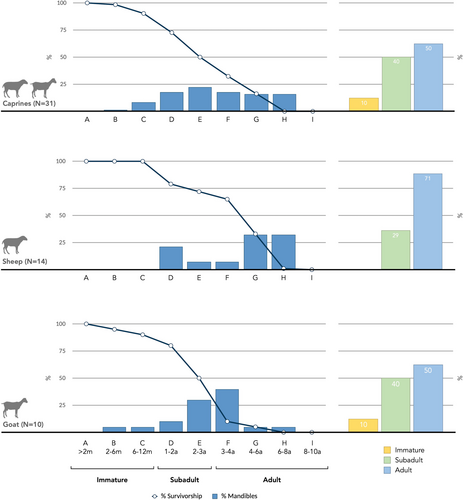

Again, the limited quantity of available data prevents the analysis of the kill-off patterns of species other than sheep and goats, for which it was necessary to combine the three samples into a single unit of analysis. Slaughter ages based on dental eruption/wear reveal slight differences between both species, with a mortality peak between the third and fourth years in the case of goats, and two peaks (during the second year and between fifth and sixth years) in the case of sheep (Figure 5). The almost total absence of immature individuals killed during their first year is also noteworthy. Aging data based on patterns of epiphyseal fusion of postcranial bones (Table 2) are consistent with the pattern interpreted from dental data.

| Fusion group and age range | Element | Fused | Unfused |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early (< 1.5 years) | SCd | 18 | |

| Hd | 32 | ||

| Rp | 17 | ||

| P1p | 39 | 2 | |

| P2p | 23 | ||

| % young animals | 2 | ||

| Middle (1.5–2.5 years) | Td | 24 | 8 |

| MPd | 20 | 13 | |

| % young animals | 32 | ||

| Late (2.5–3.5 years) | Up | 1 | 4 |

| Fp | 8 | 4 | |

| CA | 7 | 6 | |

| Rd | 10 | 9 | |

| Hp | 1 | 4 | |

| Fd | 2 | 4 | |

| Tp | 3 | 7 | |

| % young animals | 54 | ||

| % young animals | 23 | ||

| N | 266 | ||

The analysis of butchery marks on caprines has provided interesting insights into the meat processing and distribution system and, particularly, the ethno-religious identity of consumers. Due to the low number of remains with butchery marks in both LOC-2 (n = 22) and LOC-3 (n = 21), as well as the anatomical composition of the latter, it was necessary to reduce the analysis to sample LOC-1 (Table 3).

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Chop | 87 | 58 |

| Cut | 64 | 42 | |

| Function | Skinning | 8 | 4 |

| Quartering | 84 | 47 | |

| Filleting | 32 | 18 | |

| Marrow extraction | 26 | 15 | |

| Porging | 28 | 16 | |

| % bones with butchery marks | 42 | ||

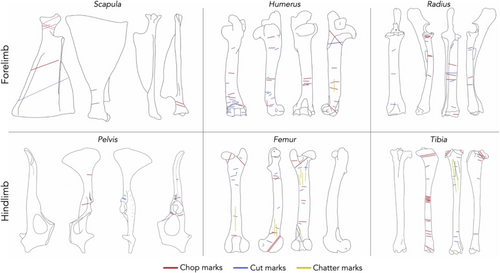

The number of remains that present butchery marks is quite high (a little less than half of the total), suggesting that carcasses of caprines were intensively used. Most are percussion marks, inflicted with a heavy tool such as a hatchet or cleaver; the number of knife marks is slightly lower. The type, position, and orientation of the marks suggest that their aim was mainly to quarter limbs and, to a lesser extent, to extract the bone marrow and to cut the meat off the bone. The recording system, including drawing butchery marks on templates (Figure 6), illustrates that butcher marks presented a relatively standardized pattern.

However, the most significant result of the analysis of butchery is the presence of a particular pattern of marks on femora and tibiae which is typically associated with kosher butchery, resulting from the process of porging (nikkur) and consisting of “the cutting away of forbidden fat and veins from kosher meat” (Eisenstein 1905, 132). Most of the porging is performed on the hindquarters because the presence of certain nerves (particularly, the gid hanasheh, i.e., sciatic nerve), large blood vessels, and the chelev (prohibited fats) is more abundant and more difficult to remove than in the forequarter (Lisowski 2019; Zivotofsky 2006). Figure 7 illustrates some examples of femora with those marks: proximal epiphysis removed by chopping (Figure 7a), longitudinal striations on the shaft (Figure 7b), and chatter marks (Figure 7c) (cf. Lisowski 2019). Although the number of bones with marks consistent with porging is not excessively high (Table 3), it is useful to apply a qualitative—rather than a quantitative—approach to the analysis of this issue, whose presence represents a clear ethno-religious marker for the zooarchaeological identification of medieval Jewish communities.

5 Discussion

The zooarchaeological assemblage from the Jewish quarter of Lorca is sufficiently representative to offer a first glimpse into the ways in which animals were exploited, the systems of meat distribution, the food consumption habits, and the religious identity of this medieval Jewish population during the 15th century.

Taxonomically, the assemblage is dominated by the remains of domestic animals (mostly mammals), with the presence of equids and wild species being very scarce, and thus reflecting food patterns that comply with the dietary prescriptions of the kashrut. Caprines are by far the most numerous taxonomic group (81% NISP). The exploitation of both sheep and goats seems to be oriented towards secondary products and, only secondarily, meat. It is striking that pig and rabbit remains—two non-kosher species—are not entirely absent, although their presence is scarce (2% NISP and 3% NISP, respectively). With regard to the pig, Lisowski (2019: 298-304) points out a number of factors that may explain its presence in Jewish zooarchaeological assemblages, including noncultural reasons (deposition and taphonomy) and cultural ones (presence of non-Jews in Jewish contexts, meat vendor's mistake or ill will, intentional leniency or transgression, economic factors and religious identity change). Therefore, the occurrence of pig and rabbit in the Lorca archaeofaunal assemblage is not straightforward to interpret, but we should not rule out the possible acculturation of at least part of this population and the occasional consumption of both species.

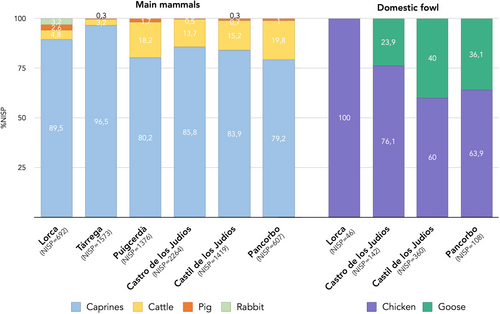

Figure 8 presents the frequency of the main domesticates together with Sephardic cases published to date. Comparison with other peninsular Jewish cases reveals broadly similar taxonomic compositions, differing only in the slightly higher frequency of pig and rabbit. However, the major difference is represented by the complete absence of goose (Anser anser) remains, a bird commonly found in other peninsular Jewish contexts such as Castil de los Judíos (García in press), Atienza (Mattei et al. 2024), Castro de los Judíos (Fernández and Martínez 2015), Pancorbo (Grau 2023) and Castrillo Mota de Judíos (Moreno 2023). Although the absence of goose might be related to the overall low number of bird remains identified in Lorca, the comparison with other Jewish sites is striking and perhaps indicates specific consumption patterns in this site that do not include this species.

The other species identified are represented by a very small number of remains, which prevents a detailed analysis, including a few remains of partridge, pigeon, deer, rat, and tuna, the latter species indicating the existence of supply networks connecting the settlement with the coast.

The unique composition of sample LOC-3, dominated by foot bones of caprines (possibly only goat), could reveal the existence of different food patterns, suggesting socioeconomic differences or the disposal of primary butchery waste in this peripheral sector, because they comprise elements with little or no meat yield.

Focusing on caprines, and contrary to what was observed in the Catalan Jewish cases of Tàrrega and Puigcerdà (Valenzuela et al. 2014), an underrepresentation of elements from the hindquarters has not been clearly noted. As it has been mentioned previously, Jewish dietary laws forbid the consumption of blood and prohibited fats (particularly abundant in the hindquarter), which is considered more serious than eating pork and incurs the severe punishment of karet, while eating the sciatic nerve incurs lashes (Zivotofsky 2006). As a consequence, medieval Jewish communities had two possibilities: either to sell hindquarters to non-Jewish customers or to perform porging (Lisowski 2019). In this regard, one of the most interesting results of this study has been the identification of butchery marks consistent with porging, which, to our best knowledge, represent the first published evidence in Iberia of this type of kosher butchery, which has also been identified in Castil de los Judíos (Molina de Aragón, Guadalajara) (García in press).

Written sources demonstrate the concern of the Sephardic communities to avoid the consumption of the sciatic nerve, referred to in medieval Iberian references as landrecilla (Cantera 2003). Inquisition trial documents show that Jewish women used to devein, degrease, wash, and salt meat in the domestic sphere (Cantera 1989, 2003; Fraile 1998), which reflects the key role played by women's religious agency as keepers of Jewish traditions (García in prep.; Starr-LeBeau 2003; Zozaya 2011). However, during the Middle Ages, porging would normally be performed by a highly trained specialist called menakker, who, moreover, was not allowed to be a butcher because it was understood that self-interest might interfere with the proper performance of his duty (Eisenstein 1905). In fact, as the statutes of the butcher's shop of the Jewish aljama of Zaragoza reveal (Lacave 1975), the meat had to be sold after having been deboned and the bones discarded. Therefore, we can assume that the domestic practice of deveining was carried out on previously deboned meat and only in those cases in which, for whatever reasons, it was not possible to guarantee that forbidden fats, nerves, and veins were properly removed. Consequently, it might be suggested that the marks observed were performed by a professional menakker, which reflects the importance and level of complexity of the Jewish community of Lorca, given that such a butchery style requires good organization (Lisowski 2019, 304).

Nonetheless, we need to bear in mind that, as also indicated by Lisowski (2019, 297), porging produces meatless bone cylinders, which, in principle, could be found among butchery waste, but less commonly in kitchen or table waste such as that examined here. Although there is archaeological evidence of a butcher's shop in the Jewish quarter of Lorca (Gallardo and González 2009, 177–181), we do not currently have any zooarchaeological material associated with this space. Therefore, the occurrence of defleshed bone cylinders (whose only food value is marrow), among the domestic refuse of House 7, physically—and possibly also functionally and symbolically—linked to the synagogue of Lorca, requires an explanation. Again, M. Lisowski (2019, 309–312) pointed out that marrow bone was a traditional ingredient of one of the most distinct and traditional Jewish dishes, the famous tsholnt, which among Sephardic Jews was called adafina or hamin (Cantera 2003; Fraile 1998). Adafina was considered “the quintessential Shabbat dish of the Sephardic Jews of the fifteenth century” (Jawhara 2021, 81), for which mutton—instead of beef, more common in Ashkenazi recipes (Kressel 2007, 664)—was used. Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that the findings of porged bones in House 7 may indicate the consumption of this particular dish by the inhabitants of the central area of the Jewish quarter, although this possibility needs to be further investigated in future studies.

6 Conclusions

The main purpose of this short article concerns the study of the animal remains assemblage recovered from Lorca castle. It has been possible to broadly characterize the production, distribution, processing, and consumption patterns of animal products by the population that inhabited this area of the town between the 14th and 15th centuries. The study represents a significant addition to the existing Jewish zooarchaeological corpus in the Iberian Peninsula and contributes to improve our understanding about daily life of Castilian ethno-religious minorities during the Middle Ages.

The results are in line with those observed by other authors in medieval Jewish contexts studied to date in Iberia. In general terms, caprines (sheep/goat) predominate, followed by cattle, chicken, and a few remains of pig and rabbit. Nonetheless, our results also indicate certain differences in comparison to other Iberian Jewish sites, namely, the absence of goose and, particularly, the identification of bones from the hindquarters of caprines that display butchery marks consistent with the porging (or nikkur) pattern described by Lisowski (2019) typical of medieval Jewish communities. In this regard, the data that inform us about the practice of porging (specifically, the removal of the heads of femora, and the presence of scratching marks on the shafts of these bones associated to scrapping all meat and fat out) represent a clear marker of sociocultural identity that demonstrates the analytical potential of zooarchaeology for identifying Jewish populations in the absence of other types of evidence.

Acknowledgments

This research was developed thanks to the Project “Los judíos del Reino de Murcia durante la Baja Edad Media: cultura material, documentos y memoria” (21864/PI/22), funded by Fundación Séneca (Agencia Regional de Ciencia y Tecnología, CARM), and it is framed within the Synergy Project MEDGREENREV funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's HORIZON ERC programme (Grant agreement No. 101071726), and the CILANTRO Project (A-HUM-239-UGR23), funded by Consejeria de Universidad, Investigacion e Innovacion and by the ERDF Andalusia Program 2021-2027. The authors are grateful for the helpful comments provided by three anonymous reviewers which improved the manuscript. Thanks are also due to the special issue editors for their work during the editing process. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada / CBUA.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.