Self-Efficacy in People With Chronic Disease: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Aim

To clarify the meaning of the concept of self-efficacy for people with chronic disease, I will use the existing literature.

Design

Concept analysis.

Methods

Systematic search in Pubmed, Scopus, and OVID databases (January 2018 to November 2023). 30 peer-reviewed articles were included in the study and analysed using Rodgers' Evolutionary Method of Concept Analysis.

Results

Five attributes were identified: motivation, individual perception, judgement, direct experience, and self-regulation. The most relevant antecedents were: educational level, social modelling, verbal persuasion, physiological and emotional states, coping styles, and health literacy. The consequences found corresponded to the influence on quality of life by enabling people to face life's challenges with confidence in their ability to handle stressful situations and overcome obstacles. Self-efficacy is thus a consistent predictor of self-care and treatment adherence.

Conclusion

Nurses will be enabled to recognise attributes and antecedents to be enhanced in educational interventions to guide the target population in decision-making and problem-solving. Theoretical basis has been provided for future research on intervention approaches to enhance self-efficacy, and to develop a scale that reflects all of the defining attributes.

Implications

Nurses using this knowledge to design educational interventions focused on identified attributes and antecedents of self-efficacy may improve treatment adherence and self-care in patients with chronic diseases, leading to improved quality of life. The development of a scale based on these attributes would provide a more accurate assessment and personalised interventions.

Impact

The need for a clarified concept of self-efficacy was addressed. Five attributes of the concept were identified. This research will have an impact on: First, researchers intending to dig deeper into this; second, healthcare measurement scale developers as the need for a scale based on the attributes of the concept has been identified; third, healthcare professionals who assist chronic patients; and finally, chronic patients who will benefit from improved interventions.

Reporting Method

N/A.

Patient or Public Contribution

No patient or public contribution.

Abbreviations

-

- CHF

-

- congestive heart failure

-

- CKD

-

- chronic kidney disease

-

- COPD

-

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

- CVA

-

- cerebrovascular accident

-

- N/A

-

- not applicable

-

- NCDs

-

- noncommunicable diseases

1 Introduction

The increasing prevalence of chronic diseases in the world's population has driven the need to better understand the factors that influence patients' ability to manage their condition. Among these factors, self-efficacy has been highlighted as a crucial element in self-care and adaptation to illness.

In nursing, self-efficacy has been adapted as an important predictor of self-care levels and has become a crucial factor in the motivation necessary to adopt healthy behaviours or stop those that harm health. However, self-efficacy is used interchangeably with other concepts such as self-management and self-care, thus losing coherence and accuracy. Mistaking the concept for others diminishes its usefulness.

The importance of clarifying the concept of self-efficacy in people with chronic diseases lies in its potential to improve health interventions, optimise clinical outcomes and increase patients' quality of life. A more precise understanding of this concept would allow health professionals to design more effective strategies to strengthen self-efficacy, which in turn could lead to better disease management and greater adherence to treatment.

To achieve this conceptual clarification, we propose to use Rodgers' evolutionary method, a rigorous and systematic methodology for the analysis of concepts in health sciences. This approach, which is based on the idea that concepts evolve over time and are influenced by context, allows self-efficacy to be examined from multiple perspectives, considering its use in the scientific literature, its defining attributes, antecedents, and consequences.

The application of Rodgers' evolutionary method in this study will facilitate a comprehensive exploration of the concept of self-efficacy in the specific context of chronic illness, identifying how its understanding and use in research and clinical practice have evolved. This analysis will not only contribute to a clearer and more contextualised definition of self-efficacy, but will also provide a solid foundation for future research and the development of more effective interventions in chronic disease management.

2 Background

Chronic diseases represent an enormous public health challenge. The proportion of total global deaths caused by chronic diseases (NCDs) is expected to increase to 70% and the global burden of disease to increase to 56% by 2030. Many people with NCDs have poor self-care skills, which may be related to low self-efficacy; this situation triggers a significant impact on functioning, quality of life and well-being, as it has implications for productivity and health care costs for society (Al-Maskari 2010; GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators 2018). Self-efficacy becomes that first link in achieving self-care behaviours and refers to an individual's self-perceived ability to act effectively in a variety of situations. It is an important factor that influences people's ability to self-manage their chronic disease symptoms, plays an important role in determining whether self-care actions are initiated, how much effort is expended, and how long the effort is sustained in the face of obstacles and failures. People with high self-efficacy to cope with their chronic diseases reflect a perceived ability to manage challenges related to their self-care and a sense of control over their lives (Bandura 1997; Zhu et al. 2018).

Likewise, decision making regarding self-care behaviours and self-management is influenced by self-efficacy beliefs; therefore, it is of vital importance for the individual to develop a subjective concept of self-efficacy, closely related to their objective efficacy, in order to have an adequate development in daily life (Tejada 2005; Holman and Lorig 2014).

Measuring self-efficacy is useful for planning education programmes on an individualised basis, detecting individual differences between patients, as it may be an indicator for predicting important health outcomes such as hospital readmissions or quality of life (Bossen et al. 2014). Self-efficacy is a concept widely discussed in the social psychology literature to explain motivation and learning theories. In nursing, it has been adapted as an important predictor of self-care levels and has become a crucial factor in motivating individuals to adopt healthy behaviours or cease harmful health-related actions. However, self-efficacy is often used interchangeably with other concepts such as self-management and self-care, reflecting the close relationship between beliefs and behaviours that determine chronic disease management.

This conceptual overlap occurs because self-management involves practical skills, such as symptom management and treatment adherence, while self-efficacy represents an individual's confidence in their ability to perform these actions. In essence, self-management is the observable outcome, whereas self-efficacy is the psychological process that underpins it. For this reason, in scientific literature and clinical practice, both terms are often used interchangeably. However, despite their interdependence, the lack of conceptual differentiation can dilute precision in research and intervention design. Although self-efficacy is a partially mature concept, terminological clarity is essential to ensure its effective implementation in the discipline and to maximise its impact on health outcomes (Fernández 2011; Eller et al. 2018).

3 Data Sources

The Evolutionary Method of Concept Analysis was chosen as the design for this study. This method recognises that a concept is constantly evolving. According to Rodgers, concepts are considered to change, grow, and develop to improve and maintain clarity and utility in the discipline (Rodgers and Knafl 2000). To help people with chronic disease clarify the concept of self-efficacy, it was necessary to identify the context of its use and disciplinary perspectives to understand its utility.

- Identifying the name and concept of interest and association expressions.

- Identifying and selecting the appropriate setting.

- Collecting the data.

- Analysing the data: attributes, antecedents.

- Identifying an exemplar of the concept.

- Implications, hypotheses, and implications for further development of the concept (discussion).

A systematic search was carried out in the databases PubMed, Scopus, and Ovid to identify scientific articles concerning self-efficacy in people with a chronic disease. According to the Evolutionary Method, a concept should be assumed to be developed over time (Rodgers and Knafl 2000). Therefore, a time frame was applied to reduce the sample size.

The systematic search included articles that met specific inclusion criteria to ensure the relevance and quality of the selected studies. Research employing quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches published in English between January 2018 and November 2023 was considered. Original studies and systematic reviews examining the relationship between self-efficacy and chronic disease management were included, addressing aspects such as symptom management, treatment adherence, lifestyle changes, and long-term clinical outcomes. The target population consisted of patients aged 18 years and older diagnosed with chronic diseases.

Studies involving participants under 18 years of age, as well as research analysing self-efficacy in contexts unrelated to chronic diseases—such as caregivers, university students, healthcare professionals, or working populations—were excluded. Articles focusing on academic, athletic, or professional self-efficacy were also omitted to maintain a clear focus on the health and self-care of patients. The search strategy used was “self-efficacy AND patient AND chronic diseases NOT self-care”.

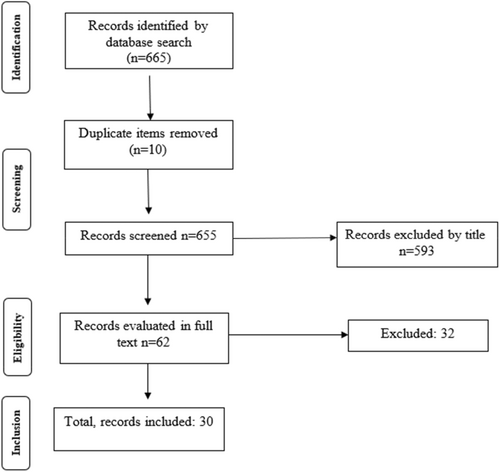

Initially, two reviewers independently analysed the titles and abstracts of each retrieved article to identify possibly eligible studies. Inconsistencies were discussed and studies that did not clearly meet the eligibility criteria were excluded (n = 593). A total of 62 studies remained, which were read in full text, from which 30 studies were finally selected (see flowchart (Figure 1)).

All of the 30 items (see Table 1) were manually sorted into a data matrix by collecting individual words and sentences from each item that could be associated with the predetermined categories: attributes, surrogate and related terms, antecedents, and consequences. This information was then entered into a coding sheet. All items were read and coded separately. The codes were then compared and discussed among the authors to reach consensus on the codes and how these related to each other and to the predetermined categories. The analysis of the extracted data was discussed within the group of authors to reach a consensus on the understanding of the concept of self-efficacy.

| Number | Author | Title | Disease | Country | Scope | Design-method-sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Li et al. (2022) | General self-efficacy and frailty in hospitalised older patients: The mediating effect of loneliness | Non-specific chronic disease | China | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study – General self-efficacy scale—convenience sampling—n = 397 participants |

| 2 | Yi et al. (2021) | Self-Efficacy Intervention Programs in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Narrative Review | COPD | China | Quantitative | Narrative review |

| 3 | Darawad et al. (2018) | Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale: Validation of the Arabic Version Among Jordanians with Chronic diseases |

COPD Diabetes Cardiovascular disease |

Arabia | Quantitative | Cross-sectional descriptive study. n = 357 participants—Exercise self-efficacy scale (ESE-A) |

| 4 | Wu et al. (2022) | Associations between e-health literacy and chronic disease self-management in older Chinese patients with chronic non-communicable diseases: a mediation analysis | Chronic disease | China | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study involving 289 participants—General self-efficacy scale |

| 5 | Wang et al. (2023) | Self-Efficacy, Coping Strategies and Quality of Life among Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B | Chronic Hepatitis | China | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—193 participants—Self-efficacy scale for chronic disease coping |

| 6 | Ebrahimi Belil et al. (2018) | Self-Efficacy of People with Chronic Conditions: A Qualitative Directed Content Analysis |

Rheumatoid arthritis Myocardial infarction Multiple sclerosis Hypertension Diabetes mellitus Chronic renal insufficiency COPD |

Iran | Qualitative | Sequential exploratory mixed method—16 participants—Semi-structured interview |

| 7 | Kaşıkçı (2011) | Using self-efficacy theory to educate a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A case study of 1-year follow-up | COPD | Turkey | Mixed | Case study mixed method approach—1 participant—semi-structured interview—COPD self-efficacy scale |

| 8 | Cudris-Torres et al. (2023) | Quality of life in the older adults: The protective role of self-efficacy in adequate coping in patients with chronic disease | Non-specific chronic disease | Colombia | Quantitative | Correlational design and a survey-type data collection method—325 participants |

| 9 | Corona et al. (2022) | Autoeficacia emocional y aspectos psicosociales en la persona que convive con enfermedad crónica | Non-specific chronic disease | Mexico | Quantitative | Descriptive and cross-sectional study—106 participants—perceived self-efficacy scale in emotional management |

| 10 | Hartman et al. (2013) | Self-efficacy for physical activity and insight into its benefits are modifiable factors associated with physical activity in people with COPD: a mixed-methods study | COPD | Netherlands | Mixed | Observational study combining qualitative and quantitative approaches—113 participants—semi-structured interview |

| 11 | Tülüce and Kutlutürkan (2018) | The effect of health coaching on treatment adherence, self-efficacy, and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | COPD | Turkey | Quantitative | Experimental study with a non-randomised control group—54 participants—COPD Self-Efficacy Scale |

| 12 | Bakan and Inci (2021) |

Predictor of self-efficacy in individuals with chronic disease: Stress-coping strategies |

Heart disease Diabetes Pulmonary disease |

Turkey | Quantitative | Cross-sectional correlational study—178 participants—self-efficacy scale |

| 13 | Kazak et al. (2022) | Evaluation of the relationship between health literacy and self-efficacy: A sample of haemodialysis patients | Chronic Kidney Disease | Turkey | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—198 participants—general self-efficacy scale |

| 14 | Lee et al. (2017) | Physical Functioning, Physical Activity, Exercise Self-Efficacy, and Quality of Life Among Individuals with Chronic Heart Failure in Korea: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Study | Cardiac insufficiency | Korea | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—116 participants—exercise self-efficacy scale |

| 15 | Wu et al. (2023) |

Chinese Community Home-Based Aging Institution Elders' Self-Management of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Its Interrelationships with Social Support, E-Health Literacy, and Self Efficacy: A Serial Multiple Mediation Model |

Hypertension Diabetes | China | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—289 participants—general self-efficacy scale |

| 16 | Lee et al. (2019) | Multidimensionality of the PROMIS Self-Efficacy Measure for Managing Chronic Conditions Multidimensionality of the PROMIS Self-Efficacy Measure for Managing Chronic Conditions | Chronic disease | USA | Quantitative | Descriptive methodological study—1087 participants- PROMIS self-efficacy scale |

| 17 | Dinh and Bonner (2023) | Exploring the relationships between health literacy, social support, self-efficacy and self-management in adults with multiple chronic diseases |

CHF Hypertension CKD Diabetes |

Vietnam | Quantitative | Cross-sectional descriptive study—600 participants—Self-efficacy scale for chronic disease management |

| 18 | Rabiei et al. (2022) | The effects of self-management education and support on self-efficacy, self-esteem, and quality of life among patients with epilepsy | Epilepsia | Iran | Quantitative | Quasi-experimental study—70 participants—Sherer's self-efficacy scale |

| 19 | Marino et al. (2008) | Impact of social support and self-efficacy on functioning in depressed older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | COPD | USA | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—156 participants—Liverpool Self-Efficacy Scale |

| 20 | Hladek et al. (2020) | High coping self-efficacy associated with lower odds of pre-frailty/frailty in older adults with chronic disease | NCDs | USA | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—146 participants—Coping self-efficacy scale |

| 21 | Jackson et al. (2014) | Domain-Specific Self-Efficacy Is Associated with Measures of Functional Capacity and Quality of Life among Patients with Moderate to Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | COPD | USA | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—325 participants—COPD self-efficacy scale |

| 22 | Chow and Wong (2014) | The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Short-form Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scales for older adults | NCDs | China | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—163 participants—Short self-efficacy scale |

| 23 | Almutary and Tayyib (2021) |

Evaluating Self-Efficacy among Patients Undergoing Dialysis Therapy |

CKD | Arabia | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—190 participants—chronic kidney disease self-efficacy scale |

| 24 | Tan-Kristanto and Kiropoulos (2015) | Resilience, self-efficacy, coping styles and depressive and anxiety symptoms in those newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis | Sclerosis | Australia | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study—129 participants—Multiple sclerosis self-efficacy scale |

| 25 | Shulman et al. (2019) | Comparative study of PROMIS self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions across chronic neurologic disorders | Chronic neurological diseases (CVA; Parkinson's, sclerosis) | USA | Quantitative | Methodological study—834 participants—self-efficacy scale for chronic disease |

| 26 | Yu et al. (2019) |

Effect of Comprehensive Therapy based on Chinese Medicine Patterns on Self-Efficacy and Effectiveness Satisfaction in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients |

COPD | China | Quantitative | Randomised clinical trial—216 participants—Self-efficacy scale |

| 27 | Bonsaksen et al. (2012) | Factors associated with self-efficacy in persons with chronic illness | NCD | Norway | Quantitative | Prospective longitudinal study—312 participants—Perceived self-efficacy scale |

| 28 | Selzler et al. (2020) | Self-efficacy and health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A meta-analysis | COPD | Canada | Quantitative | Systematic review—Meta-analysis—23 studies—2768 participants |

| 29 | Farley (2020) | Promoting self-efficacy in patients with chronic disease beyond traditional education: A literature review | NCD | USA | Quantitative | Integrative review—24 articles—1314 participants |

| 30 | Velásquez (2012) | Historical-Conceptual Review of the Concept of Self-Efficacy | NCD | Chile | N/A | Historical conceptual review |

- Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; NCD, noncommunicable disease.

- Source: Results from selected articles.

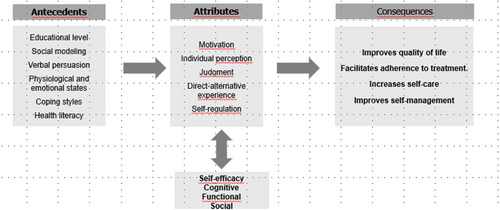

4 Overview of the Concept

The analysis resulted in a model that describes the self-efficacy concept in the person with a chronic disease (see Figure 2). The attributes identified in this study led to the following descriptive definition of the concept: Self-efficacy refers to the confidence, perception, and belief in the ability of an individual with a chronic disease to organise, implement, execute, and evaluate the necessary actions to develop skills and successfully adopt and maintain self-care behaviour (Li et al. 2022; Yi et al. 2021; Darawad et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2023; Ebrahimi Belil et al. 2018; Kaşıkçı 2011; Cudris-Torres et al. 2023; Corona et al. 2022; Hartman et al. 2013; Tülüce and Kutlutürkan 2018; Bakan and Inci 2021; Kazak et al. 2022; Lee et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2023; Lee et al. 2019; Dinh and Bonner 2023; Rabiei et al. 2022; Marino et al. 2008; Hladek et al. 2020; Jackson et al. 2014; Chow and Wong 2014; Almutary and Tayyib 2021; Tan-Kristanto and Kiropoulos 2015; Shulman et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2019; Bonsaksen et al. 2012; Selzler et al. 2020; Farley 2020; Velásquez 2012).

There are three types of self-efficacy: cognitive, functional, and social (Ebrahimi Belil et al. 2018). Cognitive self-efficacy is the chronic patient's ability to develop their knowledge and understanding regarding illness and self-care through people and scientific and online resources. Functional self-efficacy means that people with a chronic disease can plan their lifestyle and self-care with confidence in their perception of their own abilities to perform daily and self-care activities. Social self-efficacy consists of the perceptions that the chronically ill person has about their own ability to perform well in family, work, and interpersonal relationships.

5 Attributes

- Motivation: The drive that mobilises the person to take action and maintain a healthy lifestyle. In the case of chronic diseases, motivation can be a key factor in maintaining adherence to treatments and following medical recommendations.

- Individual perception: Individual perception refers to how people perceive their own situation and how they cope with problems related to their disease. A proper perception of the situation can help people make informed decisions and cope effectively with challenges.

- Judgement: The ability to assess situations and make decisions based on available information. In the context of self-care, good judgement can help people with chronic disease make informed decisions about their own health, such as following treatments and adopting healthy habits.

- Direct-alternative experience: Refers to the people's ability to experience and value the consequences of their actions and decisions in relation to their health. A well-developed direct-alternative experience can help people with chronic diseases to recognise the importance of their habits and decisions on their own health and to take actions to improve it.

- Self-regulation: The ability to manage thoughts and actions to achieve goals in order to develop positive self-care behaviours. There are three characteristics to develop it: magnitude, which refers to the level of difficulty that a person believes they can face. The person evaluates their ability to perform a specific task and determines whether it is easy or difficult for them. Strength refers to the self-conviction that one is strong or weak. That is, the person evaluates their ability to cope with difficult situations and determines whether they feel strong or weak. Generality refers to the degree to which the person evaluates their ability to perform different tasks and determines whether their belief in their ability is generalised or specific to a particular task.

6 Antecedents

- Educational level: Self-efficacy is closely related to the level of education. Patients with a higher level of education have a deeper understanding of the disease and greater confidence in the lifestyle changes to be made.

- Social modelling: Observing others who are successful in performing similar tasks, that is, learning from other similar cases can provide tangible and observable experience.

- Verbal persuasion: This can influence self-efficacy by providing support, encouragement, and conveying positive information about the person's ability to manage their disease.

- Physiological and emotional states: The decompensation derived from the disease can generate anxiety and stress, which influence the perceived self-efficacy. This shows the necessity to recognise the number of relapses and previous experiences.

- Problem-focused coping styles: Defined as actively addressing challenges and treatment-related difficulties, and developing positive self-care behaviours. These styles can strengthen self-efficacy by providing individuals with concrete strategies for coping with their condition.

- Health literacy: The ability of individuals to access, understand, evaluate, and use health information and services to make informed decisions about their health. In turn, it can influence self-efficacy in the person with a chronic disease, since, by having greater knowledge about their disease and its treatment, the person may feel more able to make informed decisions about their care and cope with the demands of the disease.

7 Consequences

Consequences are the results of what happens after the concept (Rodgers and Knafl 2000). The analysis showed that self-efficacy influences quality of life by enabling people to face life challenges with confidence in their ability to handle stressful situations and overcome obstacles. It becomes a consistent predictor of health behaviour adherence in the domains of physical activity, nutrition, and medication adherence, which will lead to better health outcomes. In addition, self-efficacy is linked to self-care and self-management. People with high self-efficacy tend to take an active role in their health care, adopting healthy behaviours and making informed decisions about their well-being. Likewise, people tend to be better able to cope with the demands of a disease and are less affected by negative emotions derived from their health condition (Li et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2023; Bakan and Inci 2021; Lee et al. 2017; Dinh and Bonner 2023; Marino et al. 2008; Chow and Wong 2014; Selzler et al. 2020).

8 Example of the Concept

An example demonstrates and highlights in a practical way the characteristics of a concept in a relevant context (Rodgers and Knafl 2000). A case is described below:

Carlos, 60 years old, high school education, owns a business, married, two professional children, diagnosed with arterial hypertension, overweight and dyslipidemia. During the last year he has become more aware of the need to generate changes in his self-care behaviours related to physical activity and diet, based on his previous experiences and his last relapse in which he was hospitalised for 3 weeks. Upon discharge from the hospital, he was actively involved in the chronic programme where he accessed individual educational sessions, telephone follow-up and spaces for interaction with other patients, who shared their achievements in their care based on their lived experience. He began to incorporate change by evaluating the actions that were not helping him with his disease and made the decision to start setting specific goals, starting with physical activity and diet. He is highly motivated to keep his health under control. He knows that good control of his blood pressure allows him to lead a fulfilling life and avoid serious complications. This motivation drives him to rigorously follow his treatment plan, which includes a healthy diet, regular exercise and constant monitoring of his blood pressure levels.

Carlos firmly believes that he can control his symptoms and keep his health stable through his own efforts. This belief in himself leads him to take an active role in his care. He has also developed good judgement about how he should manage his condition in different situations. He knows when to adjust his medication, how to respond to out-of-range blood pressure values, and when to seek medical attention. This judgement allows him to make informed decisions that strengthen his self-efficacy. Throughout his relapses, Carlos has accumulated valuable experiences, learned from his successes and mistakes, which have allowed him to refine his strategies and feel increasingly capable of controlling his disease. He relates that the weekly meetings in the chronic programme have provided him with many educational and experiential resources that have helped him to initiate this change. He clearly realises that it has not been an easy process, but he is a man who persists; he evaluates the degree of difficulty he has had to develop these habits.

This example shows precisely how the antecedents in the social model, educational level, physiological state derived from relapse, previous experiences, and literacy have a positive influence on the levels of self-efficacy. It is evident that motivation, individual perception, judgement, direct experience, and self-regulation are the main attributes that enable the development of confidence in the ability to develop and evaluate actions in the face of self-care. The result of this high self-efficacy is reflected in improved quality of life and adherence to treatment.

9 Implications and Hypotheses

Rodgers (Rodgers and Knafl 2000) indicate that the references describe the context or situations in which an instance of the concept is applied. The analysis showed that the concept of self-efficacy emerged from the perception, description and experience of what living with a chronic disease implies and the need to develop healthy behaviours; for that reason, self-efficacy plays an important role in determining whether self-care actions are initiated, how much effort is invested and for how long the effort is maintained in the presence of obstacles and failures. It is important to note that most of the selected studies correspond to people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (Yi et al. 2021; Darawad et al. 2018; Ebrahimi Belil et al. 2018; Kaşıkçı 2011; Hartman et al. 2013; Tülüce and Kutlutürkan 2018; Bakan and Inci 2021; Dinh and Bonner 2023; Jackson et al. 2014; Chow and Wong 2014; Yu et al. 2019; Selzler et al. 2020). This disease is characterised by a high symptom burden and compromised quality of life, which makes it necessary to promote and adopt self-care behaviours related to physical activity, adherence to pharmacological treatment and the ability to make decisions in the face of exacerbation symptoms. This shows the necessity for patients to acquire skills to control symptoms, follow the treatment plan, make lifestyle changes and prevent relapses. The development of high levels of self-efficacy can improve patients' ability to manage their disease and improve their quality of life.

10 Surrogate and Related Terms

The study did not identify any surrogate terms during the analysis and review of the literature. According to the literature, a surrogate term (Rodgers and Knafl 2000) is a means of expressing a concept other than the word or expression selected by the researcher to focus the study. Related concepts are those that have some relationship to the concept of interest, but do not share the same set of attributes, that is, they are not interchangeable. The study found related concepts such as self-care, self-management, or self-control; nevertheless, self-efficacy is a prerequisite for the behavioural performance of these related concepts.

11 Discussion

The outlining and clarification of the meaning of self-efficacy revealed that this concept is different from other related concepts such as self-control and self-care. Self-control refers to the ability to regulate and direct one's emotions, thoughts, and behaviours, while self-care refers to the actions a person takes to maintain their health.

To regulate emotions and develop healthy behaviours, self-efficacy is required, since it is the belief in a person's own ability to carry out those actions effectively. Although these are different concepts, they are closely interrelated.

Self-efficacy is a domain-specific concept that positively or negatively influences three main factors of human behaviour: the affective domain (emotions, feelings, etc.), the cognitive domain (thinking, task resolution, etc.) and the behavioural domain (behaviours) (Olivari and Urra 2007); thus, self-efficacy largely determines and predicts future behaviours and actions. For this reason, before developing interventions aimed at promoting self-care and self-management, it is necessary for nursing professionals to identify the levels of self-efficacy in order to improve people's ability to face difficulties and challenges in their care.

It was possible to observe that the concept of self-efficacy has a dynamic tendency, ranging among the components of the concept. Therefore, people with chronic diseases are influenced by antecedents preceding the attributes, and each attribute results in consequences related to it. It is evident that over time more attributes and antecedents are recognised in the concept of self-efficacy. These influence the development of the concept and allow a better understanding of how it is promoted and optimised in the context of chronic illness.

The evolution over time of the concept of self-efficacy generates the need to analyse from a critical viewpoint the theoretical references of this concept, such as the one proposed by Barbara Resnick (Resnick 2008), who defines self-efficacy as the judgement that individuals have about themselves, through reflective thinking, the generative use of knowledge and skills to perform a specific behaviour. This judgement depends on the four sources described by Bandura (Córdova-León et al. 2022) in his theory, such as performance achievements, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and the physiological state of the individual. While this definition captures the idea that self-efficacy refers to an individual's judgements and thoughts about themselves, it is a general and abstract definition.

In comparison, the concept of self-efficacy derived from this conceptual analysis is more specific and captures the key elements of self-efficacy in the context of chronic disease. It is defined as the confidence, perception, and belief in the ability of an individual with a chronic disease to organise, implement, execute, and evaluate the actions necessary to build skills and successfully achieve the adoption and maintenance of self-care behaviours.

In addition, this conceptual analysis suggests integrating the three types of self-efficacy (cognitive, functional and social) with the expectations of self-efficacy and outcomes, which are central components of the theory. Self-efficacy expectations influence the motivation and effort that the person invests in the related tasks. On the other hand, outcomes expectations influence the choice and persistence of actions to achieve the desired results. The integration of these elements allows an understanding of the self-efficacy and outcomes expectations achieved at the cognitive, functional, and social levels.

The self-efficacy theory does not specifically integrate the motivational component in the complexity of the tasks or actions from the person to change behaviour. At the same time, the empirical support of this theory has been based more on the development of the expectation of self-efficacy than on the expectation of outcome. For that reason, it would be very useful to integrate the attributes such as motivation and self-regulation identified in this analysis, as well as antecedents such as educational level, coping styles and health literacy into the information sources component of the theory. Motivation influences the way goals are set, and self-regulation allows managing thoughts and actions to achieve goals versus developing positive self-care behaviours, both of which would enhance outcome expectations. Educational level and health literacy help to increase knowledge, skills and resources to strengthen confidence and control in individuals. Coping styles help to explain the ways in which people cope with difficulties and emotional burden to generate behaviour change (Eller et al. 2018; Anekwe and Rahkovsky 2018; Willis 2016).

Finally, this analysis is of great value for nursing practice as it demonstrates the importance of this construct and its relationship with self-care and self-management, providing a solid foundation for nursing professionals to develop more effective and person-centred interventions. Self-efficacy is a key determinant in improving the care of patients with chronic diseases, as it directly influences their ability to adhere to treatments and proactively manage symptoms. When healthcare professionals design interventions that enhance self-efficacy, an increase in patients' motivation and commitment to self-care is observed. This leads to greater willingness to follow medical guidelines, make lifestyle changes, and face challenges related to their illness.

Moreover, strengthening self-efficacy enables patients to develop problem-solving skills and make informed decisions, reducing reliance on emergency services and improving long-term clinical outcomes. Additionally, integrating different types of self-efficacy and their interaction with self-efficacy and outcome expectations provides a more comprehensive and contextualised view of this construct. From a nursing perspective, focusing on self-efficacy not only enhances self-management but also humanises care, empowering patients and fostering a collaborative relationship that supports continuity of care. Collectively, these findings can guide the improvement of tools and the design of evaluation and intervention strategies that strengthen self-efficacy in patients with chronic diseases, which, in turn, can significantly improve adverse health outcomes.

12 Strengths and Limitations

The authors made every effort to maintain methodological rigour and followed all the steps of the evolutionary method proposed by Rodgers. The number of articles selected and the delimitation of the search minimises the risk pointed out by Rodgers, where a larger volume of data can affect the analysis and identification of a concept and hinder data processing. The process of critical reading, extraction, and selection of categories was carried out in a group of three researchers.

One of the limitations was the scarcity of qualitative studies, which restricted the exploration of the concept in depth. On the other hand, most of the studies corresponded to people with COPD, thus focusing the concept on a single chronic condition; however, this chronic condition has a very similar behaviour in terms of symptom burden and quality compromise with other chronic diseases.

13 Conclusion

The concept will enable nurses to recognise the attributes and antecedents to be enhanced in interventions to guide decision-making and problem-solving when assisting the target population. This conceptual analysis also provides a theoretical basis for future research on approaches to interventions to enhance self-efficacy, as well as the need to develop a scale that reflects all of the defining attributes.

Author Contributions

Maria Mercedes Duran de-Villalobos and Alejandra Fuentes-Ramirez contributed to: analysis, interpretation, revision and approval of the final version.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the databases cited in this paper.