Development and Utilisation of the Chinese Version of Professional Attitude Scale for Nurses: Two Cross-Sectional Studies

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Aim

To translate and assess the psychometric characteristics of the Chinese version of the Professional Attitude Scale for Nurses (PASN-C) and utilise it to investigate the present status and associated factors of professional attitude among Chinese nurses.

Background

Assessing professional attitude is a crucial aspect of nursing professionalism. However, there is a significant gap in the field as no reliable instrument exists in China to assess nurses' professional attitudes.

Methods

The PASN-C was created by adapting the Brislin translation model. The participants hailed from 11 hospitals in Tianjin, China. Two cross-sectional studies were performed, in which a convenience sampling method was used to survey 877 participants (first study) to assess the validity and reliability of the PASN-C; furthermore, 1154 participants (second study) were surveyed to analyse the current status and associated factors of the professional attitudes of Chinese nurses.

Results

The PASN-C maintained 38 items and 8 factors, which explained 60.540% of the variance. The item-level content validity index (0.860–1.000), dimension-total score correlation coefficient (0.622–0.766), and Cronbach's alpha coefficient (0.943) indicated PASN-C had good validity and reliability. The score of PASN-C was 136.16 ± 15.48. Male, tertiary hospitals, specialty hospitals, high-income, obstetric nurses and specialist nurses were associated with a higher professional attitude.

Conclusions

The PASN-C is a reliable and valid instrument that can be utilised to assess Chinese nurses' professional attitudes. Furthermore, this study suggests that more attention should be paid to associated factors to improve nurses' professional attitudes.

Implications for the Profession

The PASN-C can be an effective tool to assess the professional attitude of Chinese nurses. Furthermore, nursing administrators, educators and clinical nursing practitioners could strengthen training in the dimensions of ‘autonomy of clinical judgment’, ‘work-related independence’ and ‘enhancement of nursing education’ to improve the professional attitude of nurses.

Reporting Method

This study followed and reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Public Contribution

Researchers received the data from the managers of each participating hospital after distributing the electronic survey to the participants.

1 Introduction

By the end of 2021, China had 5,018,000 registered nurses (Chen et al. 2022), as evidenced by the large number of nurses who play a crucial role in every aspect of healthcare. However, with the rapid expansion and development of the nursing profession, nurses face the challenge of specialising and integrating nursing work (World Health Organization 2020). The report entitled ‘Future of Nursing in America (2020–2030)’ states the necessity of a robust and diverse nursing workforce to enhance the health and well-being of nurses, individuals and communities and address systemic inequities that lead to widespread and persistent health disparities (Wakefield et al. 2021). It also emphasises that the professionalism of nurses needs to be carefully assessed and reviewed to determine whether it matches the rapid expansion and high-speed development of the nursing specialty and the competencies expected by the public.

Professional attitude belongs to the function of superstructure in professionalism, which profoundly impacts the development of professionalism (Hammer 2000). Professional attitudes encompass the values, affective responses and behavioural tendencies of individuals in their chosen careers (Morgan et al. 2014), reflecting nurses' attitudes toward autonomy, knowledge and meeting public expectations in the nursing profession (Takada et al. 2021). Professional attitudes indicate professional behaviours, identity, turnover intention, career satisfaction and even the development of industries (Fitzgerald 2020; Gan et al. 2020; Kundi et al. 2021). A recent study indicates that nurses' positive attitude toward evidence-based nursing is associated with their excellent professional attitude (Asi et al. 2021). Other studies demonstrated that nurses' professional attitudes positively affect their professional behaviour, collaboration and communication in the clinical setting (Merati et al. 2021; Sumen et al. 2022). Therefore, nurses' professional attitude is closely related to the development of the nursing profession.

Therefore, it is necessary to take action to analyse the professional attitudes of nurses. Based on the steps of the research procedure, evaluating the research question is the initial stage in the analysis process, which leads to an understanding of the current state of the research.

To date, two professional attitude measurement tools for nurses have been used in China (Arthur 1995; Wu et al. 2000). However, these scales were developed based on characteristics of general occupation (e.g., occupational skills and communication) and not specifically for the nurse population. Furthermore, the nursing profession constantly adapts to the current concept of continuous development and improvement of medicine, resulting in rapid changes in the nursing work environment (National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China 2016). Combined with the increasing expectations of the public regarding the professionalism of nurses led to the continuous expansion of the nursing service area and the optimization of the academic structure of nursing personnel (National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China 2016; Zhang et al. 2020). Consequently, these changes have brought new complexities to the identity of the nurses, nursing values and nursing mission. Some of the items of the previous scales may not be suitable for the current nursing situation, leaving these scales somewhat deficient in effectively measuring the professional attitudes of contemporary nurses in China. Hence, there is an urgent need to develop a validated psychometric assessment tool for nurses' professional attitudes to identify the professional attitudes of nurses in China.

The Japanese version of the Professional Attitude Scale for Nurses (PASN-J) is a reliable and valid measurement tool that has been tested among a large sample population in Japan (Takada et al. 2020). The PASN-J was developed using the trait approach to enumerate nurses' professional traits, such as professional knowledge and autonomy. Compared with previous scales (Arthur 1995; Wu et al. 2000), PASN-J has strong content specificity and clear options consistent with the current status of nursing development. However, no effective measurement tools have been introduced to evaluate nurses' professional attitudes in China. Further, there is uncertainty about the present state of professional attitudes among Chinese nurses and the specific factors involved. Therefore, we aimed to develop the Chinese version of the Professional Attitude Scale for Nurses (PASN-C) and utilise it to investigate the status quo and associated factors of professional attitude among Chinese nurses.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

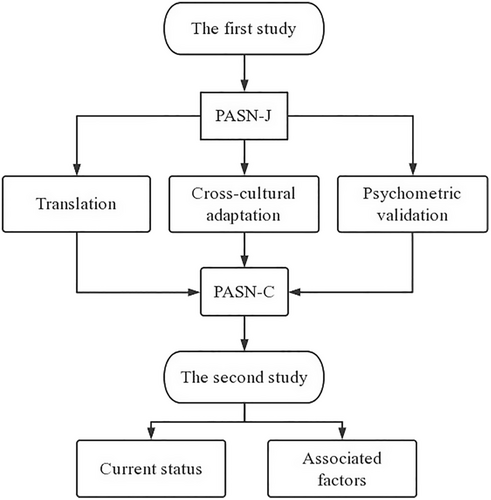

This research conducted two cross-sectional studies. The first study described how the PASN-C was translated, cross-culturally adapted and psychometrically validated. The second study investigated the current status and associated factors of Chinese nurses' professional attitudes using PASN-C. Figure 1 depicts the study design. This research was conducted following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

2.2 Participants

In Tianjin, China, a convenience sampling method was used to recruit nurses from 11 hospitals. Registered nurses with nursing qualifications who practiced clinical nursing and agreed to participate in this study were eligible. Exclusion criteria included foreign registered nurses (considering the language and cultural differences). Criteria for eliminating questionnaires were that participants' responses were regular, illogical and inconsistent.

The exploratory factor analysis method was used in the first cross-sectional study, which specifies that the ratio of each item to the number of test samples should be 1:5–1:20 (Kyriazos 2018). The number of test samples in this study was taken to be 15 times the number of test samples and the PASN-J contained a total of 38 items. Thus, it was estimated that 570 samples were needed for exploratory factor analysis and the total sample size required would be 38 × 15/0.8 = 713 after expanding the sample size by 20% by considering the invalid questionnaires. Furthermore, at least 5% of the total sample size is required as the sample size for testing the retest validity for retest validity to be reliable (Takada et al. 2020). Fifty participants were finally recruited.

The second cross-sectional study requires the data analysis method to be associated with the factor analysis; therefore, 10–20 times the number of items would be an appropriate sample size (Russo-Netzer and Icekson 2023). Considering the 20% invalid questionnaires, at least 475 participants are required for the second cross-sectional study.

2.3 Instruments

2.3.1 Demographic Questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire included 11 questions: gender, age, working years, education background, monthly income, hospital level, hospital type, professional title, work position, affiliated department and whether the participant is a specialist nurse.

2.3.2 PASN-J

PASN-J, developed by Takada, was measured the nurses' professional attitude (Takada et al. 2021). The PASN-J was a 38-item scale with 8 dimensions, explaining 60.2% of the variance in attitudes toward professional functions. This tool has five response options on a Likert scale (disagree to agree), with a total score range of 38–190. A higher score reflects better professional attitudes. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.921 in Japan.

2.3.3 The Chinese Version of the Six-Dimension (6-D) Nursing Behaviour Scale

Liu (2011) used the 6-D scale (Schwirian 1978) to create the Chinese version to measure the nursing behaviour of clinical nurses. According to the theory of Knowledge-Attitude-Practice, the occurrence of an individual's behaviour is influenced by their knowledge and beliefs (Wake 2020). This shows a theoretical correlation between nurses' professional attitudes and nursing practice behaviours, that is, nurses with good professional attitudes are perceived to have good professional behaviours.

Hence, the criterion-related validity of the PASN-C was examined using the Chinese version of the 6-D scale for the calibration. This scale used a four-point Likert scale to score the 52 items across 6 dimensions. Higher scores indicated better professional behaviour. Cronbach's alpha coefficient in this investigation was 0.959.

2.4 Translation and the Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Scale

In this study, after obtaining the authorization, the PASN-J was translated into Chinese according to Brislin's translation model (Jones et al. 2001). Translation and cross-cultural adaptation procedures consisted of four steps: (a) Two academicians with a master's degree in nursing and fluency in Japanese translated PASN-J into Chinese. Any discrepancies were discussed and revised to reach the PASN-C. (b) Two Japanese researchers with PhD degrees independently translated the PASN-C into Japanese; any differences were discussed and revised to ensure cultural equivalence. (c) The researcher contacted the original author to compare the back-translated version with the PASN-J. Seven experts in nursing, methodology and linguistics were invited to conduct the cultural adaptation and evaluate the content validity (Sousa and Rojjanasrirat 2011). A four-point Likert scale was used to score the conceptual correlation, ranging from 1 (not correlated) to 4 (highly correlated). (d) Thirty nurses who were eligible participants were selected to conduct the pre-testing (Perneger et al. 2015). Participants were invited to rate their understanding of each item, with 0 (not understanding) and 1 (understanding).

2.5 Data Collection

Data were collected from June to August 2022 and from October to December 2022, respectively, for the two studies. This study used convenient sampling and distributed online questionnaires to participants by entrusting nursing managers of each hospital. Before the data collection, the purpose of the study was clearly explained to the potential volunteers and ensured that their answers would remain anonymous. The informed consent form was filled out online by participants who gave consent. For these two online survey systems, participants need to answer every question; otherwise, the answer cannot be submitted. Furthermore, 50 participants completed the test within 2 weeks to ensure the reliability of PASN-C's test–retest.

2.6 Data Analysis

The data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Frequency and percentage were used to describe categorical variables, while mean ± standard deviation (SD) was applied to describe continuous variables. Item-total correlation, critical ratio methods and homogeneity tests were used for item analysis. The validity of PASN-C was assessed using the content validity index, internal correlation analysis, exploratory factor analysis and criterion-related validity. The content validity index (CVI) of the PASN-C was assessed using the item-level CVI (I-CVI), scale-level CVI/Universal Agreement (S-CVI/UA) and scale-level CVI/Average (S-CVI/Ave). The reliability of the PASN-C was evaluated by Cronbach's alpha, split-half and test–retest coefficients. A multivariate linear regression model was used to identify the variables connected to professional attitudes. A two-tailed p-value of 0.05 was statistically significant in this study.

2.7 Ethical Considerations

The ethical committee approved the study, and all procedures were conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration and the ethical standards of the Agency, the National Research Council (2021).

3 Results

3.1 Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

In dimension eight of the original scale, the ‘rejection of servant image’ was poorly understood under the Chinese cultural background. Indeed, tracing the historical occupational image of nurses in China revealed that the Chinese public identifies nurses as trained and educated professionals who care for the sick. This occupational group has the same social significance as ‘doctors’ (those who treat the sick) rather than an occupational image of a servant (Fan and Chen 2022). Therefore, changing the name of dimension-eight to ‘self-professional image perception’ would be more suitable for the Chinese cultural background.

Furthermore, the average pre-testing completion time among 30 participants was 6.82 min. Participants scored 1 (understood) for each item in PASN-C, indicating that they fully understood its contents.

3.2 Participant Characteristics

Two cross-sectional surveys were completed by 877 and 1154 participants, with valid recall rates of 92.4% (811) and 94.2% (1087). Most of the participants were female and came from tertiary hospitals. Table 1 depicts details of the participants.

| Variable | First study (n = 811) n (%) | Second study (n = 1087) n (%) | Score of the second study (M ± SD) | t/F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 22 (2.7) | 59 (5.4) | 143.25 ± 14.35 | 3.64 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 789 (97.3) | 1028 (94.6) | 135.76 ± 15.45 | ||

| Age (year) | |||||

| ≤ 30 | 338 (41.7) | 527 (48.5) | 136.67 ± 15.28 | 0.622 | 0.601 |

| 31–40 | 280 (34.5) | 355 (32.7) | 136.02 ± 15.99 | ||

| 41–50 | 122 (15.0) | 131 (12.1) | 134.65 ± 16.11 | ||

| ≥ 51 | 71 (8.8) | 74 (6.8) | 135.95 ± 13.21 | ||

| Working years (year) | |||||

| ≤ 10 | 439 (54.1) | 667 (61.4) | 136.58 ± 15.37 | 0.655 | 0.580 |

| 11–20 | 189 (23.3) | 225 (20.7) | 135.81 ± 15.94 | ||

| 21–30 | 118 (14.5) | 126 (11.6) | 134.56 ± 16.60 | ||

| ≥ 31 | 65 (8.1) | 69 (6.3) | 136.22 ± 12.85 | ||

| Education background | |||||

| Technical secondary school | 38 (4.7) | 38 (3.5) | 134.24 ± 14.99 | 4.961 | 0.002 |

| Junior college | 179 (22.1) | 231 (21.3) | 133.79 ± 15.82 | ||

| Undergraduate | 586 (72.3) | 800 (73.6) | 136.72 ± 15.39 | ||

| Postgraduate | 8 (1.0) | 18 (1.7) | 146.28 ± 9.53 | ||

| Hospital level | |||||

| Tertiary hospital | 659 (81.3) | 873 (80.3) | 138.81 ± 12.91 | 9.443 | < 0.001 |

| Secondary hospital | 152 (18.7) | 214 (19.7) | 125.36 ± 19.84 | ||

| Primary hospital | 4 (0.5) | — | — | ||

| Hospital type | |||||

| General hospital | 570 (70.3) | 695 (63.9) | 133.40 ± 16.12 | −8.058 | < 0.001 |

| Specialty hospital | 241 (29.7) | 392 (36.1) | 141.06 ± 12.92 | ||

| Professional title | |||||

| Primary title | 510 (62.9) | 743 (68.4) | 135.77 ± 16.12 | 0.778 | 0.460 |

| Intermediate title | 285 (35.1) | 328 (30.2) | 137.05 ± 14.07 | ||

| Vice-senior title or above | 16 (2.0) | 16 (1.5) | 136.50 ± 12.74 | ||

| Work position | |||||

| None | 670 (82.6) | 921 (84.7) | 135.88 ± 15.92 | 0.882 | 0.450 |

| Nursing team leader | 96 (11.8) | 115 (10.6) | 137.60 ± 12.34 | ||

| Head nurse | 42 (5.2) | 48 (4.4) | 137.54 ± 13.80 | ||

| Director of nursing department | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 145.00 ± 7.55 | ||

| Affiliated department | |||||

| Nursing department | 50 (6.2) | 66 (6.1) | 136.21 ± 18.51 | 3.626 | 0.001 |

| Emergency and critical care department | 89 (11.0) | 118 (10.9) | 135.68 ± 14.95 | ||

| Internal medicine department | 263 (32.4) | 392 (36.1) | 137.75 ± 15.00 | ||

| Surgery medicine department | 102 (12.6) | 125 (11.5) | 133.55 ± 14.04 | ||

| Obstetric department | 41 (5.1) | 64 (5.9) | 141.94 ± 11.53 | ||

| Paediatrics department | 17 (2.1) | 20 (1.8) | 131.25 ± 19.10 | ||

| Operating room | 108 (13.3) | 139 (12.8) | 136.05 ± 16.19 | ||

| Other hospital departments | 141 (17.3) | 163 (15.0) | 133.13 ± 16.11 | ||

| Whether participant is a specialist nurse | |||||

| Yes | 215 (26.5) | 280 (25.8) | 141.96 ± 11.26 | 8.847 | < 0.001 |

| No | 596 (73.5) | 807 (74.2) | 134.15 ± 16.22 | ||

| Monthly income (RMB) | |||||

| ≤ 3000 | — | 19 (1.7) | 115.26 ± 20.57 | 97.461 | < 0.001 |

| 3001–5000 | — | 139 (12.8) | 116.07 ± 16.85 | ||

| 5001–7000 | — | 224 (20.6) | 135.45 ± 13.91 | ||

| 7001–9000 | — | 361 (33.2) | 141.55 ± 10.27 | ||

| 9001–10,000 | — | 257 (23.6) | 139.88 ± 12.94 | ||

| ≥ 10,001 | — | 87 (8.0) | 141.36 ± 10.05 | ||

- Abbreviation: M ± SD: mean ± standard deviation.

3.3 Item Analysis

The correlation coefficient of each item varied with the PASN-C, ranging from 0.483 to 0.634 (all > 0.3 and p < 0.01). Results from the homogeneity test indicated that each item's common degree varied from 0.231 to 0.414 (all > 0.2), and the corresponding factor loading was 0.481–0.643 (all > 0.45), indicating good homogeneity among the entries (Worthington et al. 2013; Wu 2012). Moreover, the critical ratio value of each item ranged from 14.496 to 20.187 (all > 3, and p < 0.01), which indicated that each item could identify the reaction degree of different participants' characteristics (Wu 2012). Therefore, no item was excluded in the process of item analysis.

3.4 Content Validity, Exploratory Factor Analysis, Internal Correlation Analysis and Criterion-Related Validity

The I-CVI was in the range of 0.860–1.000. The respective values of S-CVI/UA and S-CVI/Ave were 0.868 and 0.982, respectively. Bartlet's test of sphericity yielded a significant result (p < 0.001), and the Kaiser–Mayer–Olkin (KMO) coefficient was 0.954 (> 0.9), suggesting that the data was particularly well-suited for factor analysis (Goretzko et al. 2021). An eight-factor model was found using exploratory factor analysis, which combined principal component analysis and varimax rotation. The factor loading of each item ranged from 0.526 to 0.792, and the eight factors' cumulative variance contribution rate was 60.540% (Table 2). Each dimension's correlation coefficient with PASN-C varied from 0.622 to 0.766 (p < 0.01). The criterion-related validity coefficient was 0.764 (p < 0.01).

| Item | Component loadings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | Factor 7 | Factor 8 | |

| 1 | 0.348 | 0.047 | 0.159 | 0.028 | 0.136 | 0.641 | 0.075 | 0.007 |

| 2 | 0.024 | 0.198 | 0.136 | 0.118 | 0.162 | 0.699 | 0.177 | 0.112 |

| 3 | 0.107 | 0.195 | 0.228 | 0.16 | 0.091 | 0.618 | 0.248 | 0.092 |

| 4 | 0.172 | 0.187 | 0.163 | 0.141 | 0.040 | 0.612 | 0.158 | 0.136 |

| 5 | 0.043 | 0.228 | 0.172 | 0.137 | 0.055 | 0.576 | 0.265 | 0.178 |

| 6 | 0.340 | 0.003 | 0.250 | 0.006 | 0.048 | 0.188 | 0.603 | 0.125 |

| 7 | 0.106 | 0.214 | 0.055 | 0.042 | 0.115 | 0.270 | 0.628 | 0.149 |

| 8 | 0.085 | 0.167 | 0.178 | 0.151 | 0.088 | 0.187 | 0.745 | 0.072 |

| 9 | 0.153 | 0.184 | 0.254 | 0.163 | 0.147 | 0.193 | 0.674 | 0.089 |

| 10 | 0.049 | 0.526 | 0.224 | 0.134 | 0.250 | 0.168 | 0.032 | 0.055 |

| 11 | 0.279 | 0.682 | 0.118 | 0.000 | 0.105 | 0.145 | 0.082 | 0.080 |

| 12 | 0.230 | 0.725 | 0.220 | 0.087 | 0.051 | 0.034 | 0.047 | 0.021 |

| 13 | 0.269 | 0.656 | 0.145 | 0.049 | 0.033 | 0.163 | 0.119 | 0.100 |

| 14 | 0.033 | 0.671 | 0.214 | 0.175 | 0.140 | 0.195 | 0.191 | 0.020 |

| 15 | −0.065 | 0.684 | 0.242 | 0.195 | 0.131 | 0.167 | 0.195 | 0.051 |

| 16 | 0.065 | 0.255 | 0.710 | 0.019 | 0.158 | 0.129 | 0.160 | 0.040 |

| 17 | 0.191 | 0.174 | 0.627 | 0.133 | 0.081 | 0.227 | 0.190 | 0.023 |

| 18 | 0.08 | 0.169 | 0.692 | 0.113 | 0.119 | 0.169 | 0.201 | 0.102 |

| 19 | 0.008 | 0.229 | 0.701 | 0.098 | 0.124 | 0.117 | 0.018 | 0.092 |

| 20 | 0.149 | 0.187 | 0.775 | 0.069 | 0.127 | 0.130 | 0.125 | 0.055 |

| 21 | 0.164 | 0.218 | 0.257 | 0.136 | 0.578 | 0.095 | 0.186 | 0.145 |

| 22 | 0.201 | 0.106 | 0.231 | 0.144 | 0.688 | 0.117 | 0.153 | 0.055 |

| 23 | 0.163 | 0.131 | 0.101 | 0.202 | 0.792 | 0.097 | 0.050 | 0.074 |

| 24 | 0.271 | 0.146 | 0.092 | 0.225 | 0.679 | 0.106 | 0.034 | 0.113 |

| 25 | 0.122 | 0.133 | 0.118 | 0.698 | 0.293 | 0.107 | 0.114 | 0.176 |

| 26 | 0.282 | 0.065 | 0.070 | 0.539 | 0.423 | 0.141 | 0.074 | 0.121 |

| 27 | 0.425 | 0.071 | 0.115 | 0.582 | 0.196 | 0.178 | 0.010 | 0.071 |

| 28 | 0.243 | 0.130 | 0.055 | 0.728 | 0.173 | 0.098 | 0.086 | 0.150 |

| 29 | 0.243 | 0.190 | 0.149 | 0.706 | 0.054 | 0.136 | 0.132 | 0.120 |

| 30 | 0.612 | 0.085 | 0.069 | 0.281 | 0.194 | 0.050 | 0.113 | 0.162 |

| 31 | 0.586 | 0.144 | 0.078 | 0.232 | 0.11 | 0.041 | 0.162 | 0.069 |

| 32 | 0.645 | 0.073 | −0.004 | 0.133 | 0.231 | 0.070 | 0.033 | 0.110 |

| 33 | 0.618 | 0.110 | 0.121 | 0.119 | 0.137 | 0.094 | 0.056 | 0.204 |

| 34 | 0.595 | 0.134 | 0.029 | 0.063 | 0.118 | 0.164 | 0.180 | 0.204 |

| 35 | 0.540 | 0.146 | 0.192 | 0.217 | 0.038 | 0.186 | 0.091 | 0.150 |

| 36 | 0.237 | 0.090 | 0.110 | 0.174 | 0.129 | 0.127 | 0.122 | 0.760 |

| 37 | 0.241 | 0.036 | 0.060 | 0.130 | 0.172 | 0.106 | 0.097 | 0.763 |

| 38 | 0.247 | 0.067 | 0.093 | 0.161 | 0.028 | 0.140 | 0.129 | 0.754 |

| Eigenvalues | 12.315 | 2.921 | 1.841 | 1.435 | 1.306 | 1.143 | 1.074 | 0.971 |

| Variance explained (%) | 32.407 | 7.686 | 4.844 | 3.775 | 3.437 | 3.007 | 2.827 | 2.555 |

| Cumulative (%) | 60.540 | |||||||

- Note: Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: varimax with Kaiser Normalisation. Component loadings over 0.4 are shown in bold. Items for each factor in the original model: building scientific nursing system: items 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5; development of professional organisation: items 6, 7, 8 and 9; enhancement of nursing education: items 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15; function to meet patients' requirements: items 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20; autonomy of clinical judgement: items 21, 22, 23 and 24; work-related independence: items 25, 26, 27, 28 and 29; self-governance of professional organisation: items 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 and 35; and self-occupation image perception: items 36, 37 and 38.

3.5 Reliability

The test–retest reliability coefficient, split-half coefficient and Cronbach's alpha coefficient for PASN-C were 0.873, 0.799 and 0.943, respectively (Table 3).

| Dimension | Item | Cronbach's α | Split-half reliability | Test–retest reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 1–5 | 0.794 | 0.793 | 0.867 |

| Factor 2 | 6–9 | 0.786 | 0.780 | 0.879 |

| Factor 3 | 10–15 | 0.835 | 0.814 | 0.889 |

| Factor 4 | 16–20 | 0.842 | 0.828 | 0.863 |

| Factor 5 | 21–24 | 0.816 | 0.793 | 0.872 |

| Factor 6 | 25–29 | 0.846 | 0.851 | 0.893 |

| Factor 7 | 30–35 | 0.798 | 0.763 | 0.847 |

| Factor 8 | 36–38 | 0.806 | 0.795 | 0.888 |

| PASN-C | 1–38 | 0.943 | 0.799 | 0.873 |

- Abbreviation: PASN-C: The Chinese version of the Professional Attitude Scale for Nurses.

3.6 Current Status and Associated Factors of Chinese Nurses' Professional Attitude

The score of professional attitudes among Chinese nurses was 136.16 ± 15.48. Moreover, three dimensions with lower scores included dimensions 3 (Enhancement of nursing education), 5 (Autonomy of clinical judgement) and 6 (Work-related independence) (Table 4). There were significant differences in professional attitude scores between nurses of different genders, educational backgrounds, monthly income, hospital level, hospital type, affiliated department and whether they were specialist nurses (Table 1).

| Variable | Score range | Score (M ± SD) | Average item score | Average sorting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 2: Development of professional organisation | 5–20 | 15.25 ± 1.70 | 3.81 | 1 |

| Factor 4: Function to meet patients' requirements | 5–23 | 18.79 ± 3.18 | 3.76 | 2 |

| Factor 1: Building scientific nursing system | 6–25 | 18.71 ± 2.34 | 3.74 | 3 |

| Factor 7: Self-governance of professional organisation | 6–29 | 22.37 ± 2.71 | 3.72 | 4 |

| Factor 8: Self-occupation image perception | 3–13 | 10.99 ± 1.67 | 3.66 | 5 |

| Factor 3: Enhancement of nursing education | 6–25 | 21.07 ± 3.84 | 3.51 | 6 |

| Factor 6: Work-related independence | 5–21 | 16.93 ± 2.92 | 3.38 | 7 |

| Factor 5: Autonomy of clinical judgement | 4–17 | 12.04 ± 2.45 | 3.01 | 8 |

| PASN-C | 61–167 | 136.16 ± 15.48 | 3.58 | — |

- Abbreviations: M ± SD: mean ± standard deviation; PASN-C: the Chinese version of the Professional Attitude Scale for Nurses.

The PASN-C score was used as the dependent variable in a multiple stepwise linear regression analysis, with statistically significant variables as independent variables in univariate analysis, and multi-categorical variables were transformed into dummy variables. The results showed that male, high-income, tertiary hospitals, specialty hospitals, obstetric nurses and specialist nurses were associated with the potential to achieve a higher professional attitude (p < 0.05) (Table 5). These factors explained 31.7% of the variance in professional attitude.

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficients beta | Standard error | Standardised coefficients beta | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 89.773 | 5.137 | — | 17.477 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | −3.825 | 1.757 | −0.056 | −2.178 | 0.030 |

| Educational background | 1.410 | 0.760 | 0.050 | 1.856 | 0.064 |

| Monthly income | 4.782 | 0.337 | 0.368 | 14.182 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital level | 9.612 | 1.067 | 0.247 | 9.007 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital type | 2.419 | 0.984 | 0.075 | 2.459 | 0.014 |

| Whether participant is a specialist nurse | 4.699 | 0.914 | 0.133 | 5.139 | < 0.001 |

| Nursing department | −2.138 | 1.956 | −0.033 | −1.093 | 0.275 |

| Emergency and critical care department | −0.690 | 1.615 | −0.014 | −0.427 | 0.669 |

| Internal medicine department | 0.490 | 1.314 | 0.015 | 0.373 | 0.709 |

| Surgery medicine department | −1.548 | 1.589 | −0.032 | −0.974 | 0.330 |

| Obstetric department | 4.306 | 1.926 | 0.065 | 2.236 | 0.026 |

| Paediatrics department | −4.955 | 3.059 | −0.043 | −1.620 | 0.106 |

| Operating room | 0.087 | 1.525 | 0.002 | 0.057 | 0.954 |

- Note: R2 = 31.7%, adjusted R2 = 30.9%, F = 38.283, p = 0.000. Computed by multiple stepwise linear regression analysis. ‘Affiliated department’ was input as the classification variables. Gender (1: male, 2: female); educational background (1: technical secondary school, 2: junior college, 3: undergraduate, 4: postgraduate); monthly income (1: ≤ 3000, 2: 3001–5000, 3: 5001–7000, 4: 7001–9000, 5: 9001–10,000, 6: ≥ 10,001); whether participant is a specialist nurse (0: no, 1: yes); hospital level (1: secondary hospital, 2: tertiary hospital); hospital type (1: general hospital, 2: specialty hospital).

4 Discussion

This study represents the first trait approach to evaluating nurses' professional attitudes according to occupational characteristics in China. The first study used the PASN-C to evaluate nurses' professional attitudes in China, revealing satisfactory reliability and validity. The second study showed that Chinese nurses' professional attitude is at a medium level and needs to be improved. Furthermore, male, high-income, tertiary hospitals, specialty hospitals, obstetric nurses and specialist nurses were associated with the potential to achieve a higher professional attitude.

Notably, most of the nurses in the two studies under the age of 40 accounted for 76.2% and 81.2%, respectively, indicating that nurses who participated in this study were young. Moreover, in both studies, participants with working years of less than 20 accounted for 77.4% and 82.1%. Similar to the general characteristics of nurses in China (National Health Commission 2020), the distribution of participants' ages and working years indicates that our study sample is a good representative.

4.1 First Study

The acceptable standards for I-CVI, S-CVI and S-CVI/AVE values were ≥ 0.78, ≥ 0.8 and ≥ 0.9, respectively (Almanasreh et al. 2019). In this study, the I-CVI value ranged from 0.860 to 1.000, whereas S-CVI and S-CVI/AVE were 0.868 and 0.982, respectively. Experts agreed that PASN-C could accurately measure nurses' professional attitudes.

The findings of exploratory factor analysis indicate that PASN-C has good structural validity. The reason for this result is twofold: First, the PASN-C yielded eight distinct factors, and the cumulative contribution rate was 60.54%, indicating that EFA extracts ideal common factors. Second, each item has a high load (≥ 0.5) on a single factor (Effendi et al. 2019). The number of common factors of PASN-C remains the same as the PASN-J, and the meaning of common factors was consistent with the theoretical structure of the PASN-J. Based on the original scale and the cross-cultural adaptation results, eight dimensions were respectively named ‘Building scientific nursing system’, ‘Development of professional organization’, ‘Enhancement of nursing education’, ‘Function to meet patients' requirements’, ‘Autonomy of clinical judgment’, ‘Work-related independence’, ‘Self-governance of professional organization’ and ‘Self-occupation image perception’. Furthermore, there was a strong correlation between the dimensions and PASN-C (r = 0.622–0.766, all p < 0.01). The correlation coefficient between dimensions was smaller than the correlation coefficients between dimensions and total score, suggesting that the correlations between the dimensions were not exactly equal and that the dimensions within the same trait category were different, indicating good structural validity of the PASN-C (Qiu 2013).

The Chinese version of the 6-D scale was used to calibrate the criterion-related validity of PASN-C. The results showed that PASN-C and its dimensions significantly correlate with the calibration (r > 0.4, medium to high correlation), indicating that PASN-C has good criterion-related validity (Wu 2012).

This study used both intrinsic and extrinsic reliability to evaluate the degree of stability and consistency of the results measured by the scale (i.e., the reliability of the scale) (Wu 2012). Specifically, the intrinsic reliability was measured using Cronbach's alpha coefficient and split-half reliability; the extrinsic reliability of the PASN-C was tested by retest reliability. The finding showed that Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.943 (> 0.9, indicating the result was highly favourable). Cronbach's alpha coefficient of each dimension was between 0.786 and 0.846, suggesting the internal consistency reliability of the scale was high. The split-half coefficient and test–retest reliability coefficient of the scale were 0.799 and 0.873, respectively (both > 0.7), which demonstrated that PASN-C has good reliability and cross-time stability.

4.2 Second Study

The mean score of PASN-C was 136.16 (SD = 15.48) in the second study, and the average item score was 3.58 (scoring rate was 71.66%), which showed that the professional attitudes of Chinese nurses are at a medium level and need to be improved. Chen et al. (2020) reported comparable findings in a study examining the professional attitudes of nurses with low seniority, revealing a professional attitude score of 84.65 (SD = 14.80) and an average item scoring rate of 70.54% for this group. Similarly, Zheng et al. (2021) investigated the correlation between the professional attitudes of cardiology nurses and their sense of professional gain, finding a professional attitude score of 89.39 (SD = 14.65) and an average item scoring rate of 74.49% among the cardiology nurses, which is slightly higher than the results of this study. Given that both Chen's and Zheng's studies employed the Nurses' Self-Concept Scale, originally developed by Arthur (1995), which focuses on five general occupational factors—namely, ‘management capability’, ‘communication competence’, ‘skills’, ‘flexibility’ and ‘satisfaction’—there is a risk of neglecting the unique characteristics of the nursing profession and the emerging responsibilities and missions introduced by the development of the current era has brought to the nursing profession (Pang 2022). Therefore, although the level of nurses' professional attitudes aligns with findings from previous studies, the results of this study present a distinct perspective on nurses' professional attitudes, as evidenced by the following analysis of the dimensions in the PASN-C.

The results of this survey showed that the average item scoring rates for each dimension of the PASN-C were, in descending order: ‘Development of professional organization’, ‘Function to meet patients' requirements’, ‘Building scientific nursing system’, ‘Self-governance of professional organization’, ‘Self-occupation image perception’, ‘Enhancement of nursing education’, ‘Work-related independence’ and ‘Autonomy of clinical judgment’. Therefore, the three dimensions with the lowest scores were ‘Autonomy of clinical judgement’, ‘Work-related independence’ and ‘Enhancement of nursing education’. This finding is similar to the recent study (Kolbe and Kryczka 2021), suggesting that strategies related to three dimensions need to be developed. In terms of ‘Autonomy of clinical judgement’ and ‘Work-related independence’, only a few provinces and cities in China currently allow nurses to have the independent rights to prescribe patients' clinical examination, treatments and topical drugs (Standing Committee of the Shenzhen Municipal People's Congress 2022; Ma and Ding 2018). This indicates that China is still in the exploratory stage of supporting the independence and autonomy of nurses, and the ideology that has not yet been promoted also limits the expansion of the cognitive horizons of the independence and autonomy of Chinese clinical nurses. In addition, the Guidelines for Nurses' Prescribing Rights state that long-term, systematic academic education is a stable and reliable source of prescriptive authority for nurses, and that increases in ‘Work-related independence’ and ‘Autonomy of clinical judgement’ are inextricably linked to the development of nursing education (Zhang et al. 2022). Therefore, when scores on the dimension ‘Enhancement of nursing education’ were low, scores on ‘Work-related independence’ and ‘Autonomy of clinical judgement’ also decreased. As mentioned in a previous study, the concept of professionalism has changed due to political, economic and social changes. Nurses today move toward developing professional organisations and constructing a scientific nursing system (Shohani and Zamanzadeh 2017). This explains why nurses have higher scores in the dimensions of ‘Development of professional organization’, ‘Function to meet patients' requirements’ and ‘Building scientific nursing system’. The present findings further illustrated the differences between PASN-C and other traditional measurement tools.

The results of the regression analyses in the second study showed that being male, having a high income and working in tertiary hospitals, specialist hospitals, maternity nurses and specialist nurses were associated with the potential to achieve higher professional attitudes, which explained 31.7% of the variance in professional attitude. According to Cohen (1988), the multiple linear regression model in this study displayed large effect sizes, with R2 values exceeding 26%. This suggests that the findings of this study are significant and contribute meaningful insights into the predictors of the studied variables. Specifically, male nurses have more self-leadership traits (Kang 2019), which enable them to have positive attitudes toward the autonomy of clinical judgement and work-related independence in professional attitudes (Knotts et al. 2021). Remuneration is considered a tangible indicator of employees' evaluation of their career prospects, meaning and achievements (Drott et al. 2023). Increasing monthly income effectively improves nurses' perception of their professional values, affective responses and behavioural tendencies (i.e., nurses' professional attitudes). Nurses in tertiary hospitals receive more comprehensive and standardised training; thus, their professional attitude is better than that in secondary hospitals (Yang et al. 2019). Interestingly, the findings showed that nurses in specialty hospitals have better professional attitudes than nurses in general hospitals. It might be easier for nurses in specialty hospitals to focus on their professional fields due to their specific professional priorities and characteristics, which are conducive to forming a positive professional attitude (Feyisa et al. 2022). Indeed, prior studies have found that the prognosis and satisfaction of patients in specialty hospitals are better than those in general hospitals (Leider et al. 2021; Runner et al. 2019). This could be attributed to the fact that nurses in specialist hospitals provide a higher quality of care and exhibit a more positive professional attitude. It is also believed that specialist nurses have a more positive professional attitude, which is attributed to the analogous rationale that they are easier to focus on their professional fields (Kerr et al. 2021). Specialist nurses scored higher than non-specialist nurses regarding professional attitudes, such as role clarity and a sense of community in the workplace (Drott et al. 2023).

A previous study found that internal medicine nurses have higher scores of professional self-determinations relative to obstetrics/paediatrics/psychiatry/intensive care nurses (Chen et al. 2016). In this study, only obstetric nurses were found to have significant characteristics of professional attitudes. This may be because the obstetric nurses in this study include midwives, and most obstetric complications are unpredictable but life-threatening (Kumar and Sweet 2020). Thus, obstetric nurses and midwives need to be engaged in and responsible for many roles in nursing work; they need to be prepared for childbirth and be ready for obstetric complications to provide high-quality and timely emergency obstetric care (Conlon et al. 2019). Obstetric nurses and midwives prioritise professional autonomy and independence in professional attitudes (Melo et al. 2016). Contrary to the findings of Shohani and Zamanzadeh (2017), this study, which included a limited number of postgraduate students, did not find educational background to be a significant factor influencing nurses' professional attitudes. However, notable differences in scores were observed between nurses with postgraduate educational backgrounds and those with other educational levels. Future research should increase the sample size to further investigate whether there is a significant relationship between nurses' professional attitudes and their educational background.

There are certain limitations in this study. First, this study only recruited participants in Tianjin, China, which may cause certain geographical biases. Future research needs larger sample sizes from distinct areas of China to verify the applicability of the PASN-C. Second, our second study did not consider other factors affecting nurses' professional attitudes, including personal traits and work environment. According to previous studies, situational factors (e.g., a leader's management style) compared with personal factors have a stronger influence on intrinsic affective attributes such as employees' professional attitudes and extrinsic job performance (Lin et al. 2022; Piwowar-Sulej and Iqbal 2023). For instance, a study conducted in Italy showed that nurses' satisfaction with the leadership of their managers reduced burnout and tension in their interpersonal relationships and reduced inappropriate nursing behaviours, which consequently improved patients' satisfaction with the care they received from nurses (Zaghini et al. 2020). Additionally, another study emphasised that personal factors, including psychological qualities and attitudes toward the nursing profession, play a vital role in shaping nurses' professional self-concept (Miao et al. 2024). Understanding these dynamics is essential for developing strategies that can improve nurses' professional attitudes and overall job satisfaction. Therefore, this should be carefully considered in future research.

5 Conclusions

This study conducted a translation and testing of the psychometric features of the PASN-C and investigated the current status and associated factors of professional attitude among Chinese nurses. The PASN-C exhibited favourable psychological properties, making it suitable for evaluating the professional attitudes of Chinese nurses. Nursing managers should prioritise examining associated factors and strategies related to these factors and develop evaluations to improve the professional attitudes of Chinese nurses.

6 Implications for the Profession

The PASN-C can be an effective tool for nurse managers, nurse educators and policymakers to assess the professional attitude of Chinese nurses. Efforts should be made to explore the predictors of nurses' professional attitudes and the factors that hinder and promote nurses' professional attitudes to recognise further the opportunities for improvement of nurses' professional attitudes. Furthermore, nursing administrators, educators and clinical nursing practitioners could strengthen training in the dimensions of ‘autonomy of clinical judgment’, ‘work-related independence’, and ‘enhancement of nursing education’ to improve the professional attitude of nurses.

Author Contributions

S.Z. contributed to the work design, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting the article, revising important intellectual content of the article, and the final approval of the version to be submitted. Y.Z., C.Z., Z.W., B.Z. contributed to the data acquisition, data interpretation, drafting the article and the final approval of the version to be submitted. X.L., S.Z., C.L. and J.L. contributed to the analysis of the work, data interpretation, draft the article and the final approval of the version to be submitted. T.F. contributed to the work design, data interpretation, draft the article, revised important intellectual content of the article and the final approval of the version to be submitted.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Professor Takada, who authorised the original scale. In addition, we would like to thank all participating experts, hospital leaders and nurses who participated in this study. And finally, we would like to thank KetengEdit (www.ketengedit.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethics Statement

This research was approved by the ethics committee of Tianjin Chest Hospital. Ethical Approval Number: 2022LW-003.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.