Signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: Grounded theory study in a Wuhan hospital

Abstract

Aim

Being front-line healthcare professionals is associated with possible severe information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Investigating signs of information anxiety is the first and key step of its targeted medical intervention. This study aims to explore the signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

This study is qualitative research. Grounded theory was used to classify information anxiety signs of front-line healthcare professionals.

Methods

Twenty-four front-line healthcare professionals from a general hospital with over 5000 beds in Wuhan were recruited to participate in semi-structured interviews. According to the frequency and frequency variation of signs appearing in interviews, the trends of signs during the virus encounter, lockdown, flattening and second wave were compared. Based on the interviews, those signs that were conceptually related to each other were extracted to construct a conceptual model.

Results

Psychological signs (emotion, worry, doubt, caution, hope), physical signs (insomnia, inattention, memory loss, appetite decreased) and behavioural signs (panic buying of goods, be at a loss, pay attention to relevant information, change habits) could be generalized from 13 subcategories of information anxiety signs. Psychological signs were the most in every period of the pandemic. Furthermore, psychological signs decreased significantly during lockdown, while behavioural and physical signs increased. Finally, severe psychological and behavioural signs were associated with physical signs.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the first cluster of cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection was reported in Wuhan, China, at the end of December 2019 (Sim, 2020), the increasing number of patients and pandemic-related deaths, exhausting workload, unavailability of ventilators and intensive care unit (ICU) beds and shortage of personnel protection equipment (PPE) in the COVID-19 pandemic have caused emotional and physical burnout over time among front-line healthcare professionals (Huang & Zhao, 2020). During the pandemic, front-line healthcare professionals in Wuhan hospitals were exposed to infection, contamination, work overload and isolation (Kang, Ma, et al., 2020). They had not only to obtain, judge and use necessary information related to their own medical work and daily life but also respond to extensive information demands from patients, relatives, friends and colleagues as essential information providers, which usually exceeds the information and information ability they have, and leads to a high risk of information anxiety.

Anxiety is a common psychiatric disorder in the general population, caused by the inability to resolve mental conflicts (Salari et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). Many studies have shown that being front-line healthcare professionals is associated with possible severe anxiety (Lai et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Signs are considered essential clues and the basis for identifying psychiatric disorders such as anxiety. Through observation, self-reported and experimentation (Richard et al., 2022; Spinhoven et al., 2022), various signs of anxiety have been identified, including avoidance, fear, worry, anxiety, and other psychological stress (Cankurtaran et al., 2021). Further studies confirmed associations between anxiety and signs such as diet quality (Richard et al., 2022), sleep quality (Li et al., 2022), smoking and alcohol abuse (Duko et al., 2022). Based on the above signs, targeted medical interventions were applied, among which psychotherapy, medication and physiotherapy were the most common treatments. In addition, some studies try to explore new medical interventions. For example, Deka et al. (2021) stated that listening to raga todi could be useful in reducing the state anxiety level provoked by a stressful life event like the lethal coronavirus pandemic. And Liu et al. (2022) believed that aromatherapy, especially inhalation aromatherapy, may help relieve anxiety symptoms in people with cancer.

Existing studies have indicated that various factors may contribute to the perceived altered anxiety levels among front-line healthcare professionals in emerging infectious disease pandemics, such as environmental (Sun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), sociodemographic (Huang & Zhao, 2020), psychosocial and occupational (Cao et al., 2020; Kang, Li, et al., 2020) factors. Furthermore, Alenazi et al. (2020) stated that the quality of knowledge presented on the official portals or social media will cause anxiety, which has actually attributed one of the causes of anxiety to information. However, the severity of COVID-19 and the infodemic (information pandemic) kept front-line healthcare professionals in chronic information anxiety, which is rarely studied. Their information anxiety is kind of but quite different from the anxiety in existing research. Therefore, exploring the information anxiety of front-line healthcare professionals plays a vital role in ensuring their health.

Information anxiety (IA) is produced by the ever-widening gap between what we understand and what we think we should understand. It happens when information does not tell us what we want or need to know (Wurman, 1989). Information anxiety can reduce both the work performance and the life quality of physicians, nurses and health personnel and impair their health. Currently, studies seldom explored information anxiety based on signs. Wurman (2000) stated that information anxiety can have many forms, the first of which is frustration with the inability to keep up with the amount of data in our lives. Second, the frustration with the quality of what we encounter – especially what passes as news. It can be seen that information anxiety signs are described as frustration in terms of forms. Other studies (Xiang et al., 2021) took the theory of intergroup emotion as an analytical framework to explore hotel employees' information anxiety under normal epidemic prevention measures. However, these studies have summarized information anxiety signs as negative emotions without a comprehensive analysis. With regard to research groups, many studies assessed information anxiety levels of students, workers and patients for convenience of data acquisition and the particularity of research objects in public health emergencies while ignoring front-line healthcare professionals prone to information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the signs were explored to clarify the conceptual scope of information anxiety and provide evidence for the medical institutions and governments to understand the mental and physical changes of front-line healthcare professionals in this study, thus becoming the first and key step of its targeted medical intervention.

The COVID-19 pandemic could be divided into four periods: virus encounter, lockdown, flattening and second wave (National Health Commission, 2022). Studies have shown that different periods will affect the psychological responses of front-line healthcare professionals (Samantaray et al., 2022). The information source, information content and information dissemination environment in various periods may cause different information anxiety signs in front-line healthcare professionals. The rebound of COVID-19 makes front-line healthcare professionals in Wuhan hospitals face a high risk of information anxiety again. Therefore, it is necessary to explore information anxiety signs of front-line healthcare professionals during various periods of the COVID-19 pandemic to provide a basis for understanding the psychological state of front-line healthcare professionals and paying attention to their health in various periods of public health emergencies in the future.

Thus, this study aimed to (1) understand signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) compare signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety in different periods of the COVID-19 pandemic and (3) construct a conceptual model of signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Grounded theory (GT) is a qualitative research methodology that aims to explain social phenomena (Brunet et al., 2022), which is useful when it comes to acquiring insight into new and unexplored areas, as it enables researchers to examine areas from different angles. Information anxiety of front-line healthcare professionals is a common social phenomenon during the COVID-19 pandemic, and its signs are rarely studied yet. Accordingly, grounded theory has strong adaptability and pertinence to this study.

Given the current studies about signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings will enhance the practical knowledge of medical institutions and governments for efficient dealing of mental health issues related to front-line healthcare professionals, prevent the negative effects of information anxiety and accordingly provide targeted medical intervention in public health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study setting

According to the National Health Commission in China, there were four periods of plague prevention: ① virus encounter (from December 27, 2019 to January 19, 2020), ② lockdown (from January 23, 2020 to April 8, 2020), ③ flattening (from April 9, 2020 to March 4, 2022) and ④ Second Wave (from March 5, 2022 to December 5, 2022). In the virus encounter, front-line healthcare professionals in Wuhan hospitals faced COVID-19 for the first time; In the lockdown, Wuhan was in a period of closure, and front-line healthcare professionals in Wuhan hospitals had dual pressures on work and life; In the flattening, the epidemic gradually subsided with sporadic cases of COVID-19 in China; In the second wave, the epidemic was making a comeback, and front-line healthcare professionals in Wuhan hospitals need to deal with sudden cases again. Subsequently, epidemic prevention and control became normalized until December 5, 2022, when it was announced that isolation measures will no longer be implemented for people infected with novel coronavirus, close contacts will no longer be determined, and high- and low-risk areas will no longer be delineated.

The interviews were conducted from April 16, 2022 to May 16, 2022. The interviews are in second wave. At this time, the second wave of the outbreak has just ended, and prevention and control are gradually becoming normalized. The reason for the interview time is that the interval among the first three periods is relatively short, and the epidemic prevention and control status during this period are stable, which helps participants recall their experiences of information anxiety in the four periods.

2.2 Participants and sampling

Approved by the Biomedical Ethic Committee of Wuhan University, the sample comprised front-line healthcare professionals with signs of information anxiety in the treatment and nursing of COVID-19 in a Wuhan hospital with over 5000 beds. Front-line healthcare professionals were recruited to participate in the study through network announcements, which briefly described the study. By recommendation, some participants were then snowballed the study details to other eligible potential participants (Sant, 2019). Thirty-three participants were recruited, some of whom could not complete the interview due to privacy concerns. As a result, interviews with 24 participants were used for analysis.

To ensure the screening of front-line healthcare professionals who meet the criteria of participants, they were identified and selected based on the following criteria: (1) ≥18 years of age, (2) working time ≥1 year and participated in healthcare work of the COVID-19 pandemic, (3) exclude trainees, students and off-duty workers and (4) able to read and provide informed consent, as shown in Table 1. As a result, the participants came from nine departments, including internal medicine, surgery, infection, etc.

| Demographic variable | Descriptives, n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (29.1) |

| Female | 17 (70.8) |

| Age | |

| <31 years | 3 (12.5) |

| 31–40 years | 19 (79.1) |

| >40 years | 2 (8.3) |

| Role | |

| Physician | 9 (37.5) |

| Nurse | 15 (62.5) |

| Title of a public health technician | |

| Physician/Nurse | 13 (54.1) |

| Doctor/Nurse in charge | 7 (29.1) |

| Assistant Director Physician/Nurse | 2 (8.3) |

| Director Physician/Nurse | 2 (8.3) |

| Education | |

| Bachelor | 13 (54.1) |

| Master or Doctor | 11 (45.8) |

| Working experience | |

| <6 years | 12 (50.0) |

| 6–10 years | 8 (33.3) |

| 11–20 years | 2 (8.3) |

| >20 years | 2 (8.3) |

- a n = 24.

Researchers explained the research contents and procedures in detail to 24 front-line healthcare professionals. The duration of this process should not exceed 10 min. If the participant has any doubts, they could raise them during this process. Interviews were arranged with their permission. All front-line healthcare professionals provided written informed consent prior to data collection.

2.3 Data collection

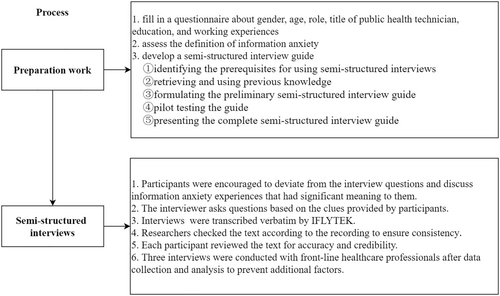

The data collection process includes preparation work and semi-structured interviews, as shown in Figure 1.

2.3.1 Preparation work

Three steps are used to complete the preparation work.

Firstly, the participants filled in a questionnaire about gender, age, role, title of public health technician, education and working experiences. In the questionnaire, participants do not need to fill in their names, but instead use their numbers to represent themselves. Before the interview, participants were informed that the information collected would be strictly confidential and anonymous (Kallio et al., 2016). In addition, participants were informed that their answers were collected for academic purposes only.

Secondly, the definition of information anxiety was assessed. The interviewer explained the definition of information anxiety to participants and provided examples. Then, the interviewer asked participants to describe an information anxiety experience in their daily lives. Based on their statements, the interviewer could confirm whether participants have an appropriate understanding of information anxiety.

Thirdly, the development of a semi-structured interview guide includes five phases: (1) identifying the prerequisites for using semi-structured interviews; (2) retrieving and using previous knowledge; (3) formulating the preliminary semi-structured interview guide; (4) pilot testing the guide and (5) presenting the complete semi-structured interview guide (Kallio et al., 2016). Information anxiety of front-line healthcare professionals is a new phenomenon in the context of the infodemic, information anxiety signs could be explored by the semi-structured interview method. Then, the interviewer used the interview guide written by several researchers familiar with the literature and the reality of front-line healthcare professionals. The interview guide included introductory questions focused on understanding the concept of information anxiety and the four periods of the COVID-19 pandemic. These were followed by main questions informed by the research aim and relevant literature that covered: (1) Do you have information anxiety in the virus encounter/lockdown/flattening/second wave? (2) Please describe your information anxiety experiences in detail. (3) What are your signs of information anxiety? During the interview, the same participant was asked about their experience and signs of information anxiety in each period.

Subsequently, the interviewer tested the interview guide with three front-line healthcare professionals who met the criteria. The purpose of the test interview was to determine if the questions were straightforward to respond to. Based on feedback received during the test interview, questions were revised. Data from the test interview were not analysed for the study.

2.3.2 Semi-structured interviews

Six steps are used to complete the semi-structured interviews.

Front-line healthcare professionals took part in one semi-structured interview face to face (n = 23) or via videoconferencing (n = 1) with a trained interviewer who was a staff member of this hospital. The interviewer was a colleague of the participants, which could ensure the convenience of communication. All of the researchers involved in the study were doctoral candidates or PhDs in information science. All researchers had more than 1 year of qualitative research experience.

Front-line healthcare professionals were encouraged to deviate from the interview questions and discuss information anxiety experiences that had significant meaning to them. Moreover, the interviewer asks questions based on the clues provided by participants, avoiding biased and guiding questions as much as possible. Expert reviews provided quality assurance for this study, which conformed to the principle of theoretical sampling (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Interviews ranged from 15 to 33 min (M = 20 min) and were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by IFLYTEK. Researchers then checked the text according to the recording to ensure consistency. Each participant reviewed the text for accuracy and credibility. All interviews were conducted in Chinese, and corpuses were presented in English.

Experts contend that there was no definitive numerical recommendation for determining sample size for a grounded theory study (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Saturation was reached within the 24 interviews based on this criterion. The reason is that three interviews were conducted with front-line healthcare professionals after data collection and analysis to prevent additional factors. The results showed that no additional factors were present in either the sign or the relationship between the signs. Based on existing literature, the number of participants in most studies ranged from 8 to 48. Therefore, 24 participants were used as research samples. Data from the three additional interviews were not analysed for the study.

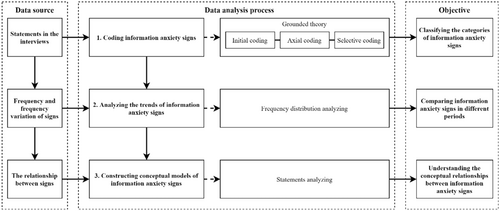

2.4 Data analysis

Coding information anxiety signs, comparing the frequency and frequency variation of information anxiety signs and constructing conceptual models of information anxiety signs were the three main steps in the data analysis process, as shown in Figure 2.

2.4.1 Coding information anxiety signs

The study followed a grounded theory analysis methodology to explore information anxiety signs of front-line healthcare professionals. Therefore, the transcribed data were analysed using open, axial and selective coding approaches (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). In the open and axial coding process, the two researchers independently coded and checked inter-coder agreement. Two experts reviewed the open and axial coding results. The controversial coding results were judged and decided by the third expert to obtain the final open and axial coding results. The subcategory with the highest frequency was regarded as the selective coding result and presented in the study. Categories of information anxiety signs were obtained by induction of correlations between selective coding results. Finally, the results were analysed by the statements and opinions of the participants.

Grounded theory analysis contains seven fundamental principles (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Montgomery et al., 2023; Silverio et al., 2021): (1) No a priori assumptions, (2) Data-driven analysis, (3) In vivo coding, (4) Constant comparison, (5) Reflexive practice, (6) Theoretical sampling and (7) Testable theory. Two researchers used NVIVO 12 for independent coding. In the coding process, researchers were not given any pre-assumptions, and the coding was completely in accordance with the interview text. Furthermore, researchers repeatedly compared the coding results and recorded the coding process and their views on the data through online shared documents (www.kdocs.cn). Once a particular category occurred, the third researcher would evaluate whether the result was caused by sampling deviation and whether all final analytical results were testable.

2.4.2 Analysing the trends of information anxiety signs

According to the frequency and frequency variation of different signs (selective coding result) appearing in interviews, the trends of information anxiety signs in various pandemic periods were compared.

2.4.3 Constructing conceptual models of information anxiety signs

The relationships between categories of information anxiety signs could be used to construct conceptual models. Those signs that were conceptually related to each other based on the statements were extracted. In the conceptual model, the related words and level of information anxiety signs also came from the statements of the participants. Only when more than half of the subcategories of information anxiety signs were given a level by the participants, the category of information anxiety signs to which the subcategory belonged would have the level. For example, severe depression, continuous state of anxiety and long-term concerns could be summarized as severe psychological signs of information anxiety.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Results of coding

Twenty-four interviews were analysed, and the categories were extracted. The coding results are shown in Table 2. Each category will be described in detail.

| Category (frequency) | Selective coding/subcategories (frequency) | Axial coding | Initial coding (examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological signs (103) | Emotion (54) | Change of emotion | A lot of news about the COVID-19 pandemic made me panic and confused |

| Worry (39) | Worry about others or yourself | When I saw the message forwarded to me by a colleague, I began to worry about infecting my family | |

| Worry about materials | News of shortages often came from the hospital, and I worried about the adequacy of medical supplies | ||

| Worry about epidemic situation | I check the number of new cases daily and worry when the epidemic is worsening | ||

| Caution (5) | Enhance awareness | Based on the protection recommendations made by experts, I have become more cautious about prevention at medical work | |

| Doubt (3) | Doubt the authenticity of the information | There was also no clear information, so I began to doubt whether the news I saw was true or false | |

| Hope (2) | Hope for a normal life | Every so often, there would be news discussions about when the epidemic would end, and I would miss the old days of not wearing a mask and wanting to live everyday life | |

| Physical signs (6) | Insomnia (3) | Insomnia | I often read everyone's comments until 2 a.m. and then start to lose sleep |

| Inattention (1) | Inattention | When I see epidemic news, my attention will be distracted | |

| Memory loss (1) | Memory loss | I occasionally experience memory loss | |

| Appetite decreased (1) | Appetite decreased | I will have the feeling of not thinking about eating | |

| Behavioural signs (27) | Pay attention to relevant information (16) | Pay attention to information | As the outbreak develops, I pay extra attention to the epidemic information |

| Panic buying of goods (6) | Panic buying of medical supplies | I also stocked up on masks for the family | |

| Panic buying of living materials | Because I saw much information about the rush of supplies, so I also began to buy food | ||

| Be at a loss (3) | Not knowing what to do | I don't know what to do because there is no information about it | |

| Change habits (2) | Change search habits | I used to browse social networking sites, but now I have to reduce the frequency of searches to avoid anxiety |

Thirteen subcategories of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety signs during the COVID-19 pandemic could be classified into three categories: psychological, physical and behavioural signs.

3.1.1 Psychological signs

Psychological signs are the psychological changes of front-line healthcare professionals caused by information anxiety, which includes five subcategories: emotion, worry, caution, doubt and hope.

Emotion is defined as flustered, frightened, fidgety and other emotional signs of front-line healthcare professionals when they experience information anxiety. For example, “I am a little nervous and uneasy because I can't get valid information about COVID-19 (P9)”. Another participant also stated, “There will be some panic, that is, because I don't know the virus and the epidemic (P14)”. Worry is defined as front-line healthcare professionals worrying about the people, materials and epidemic situations around them when they experience information anxiety. For example, “Once I see new cases around me published on the Internet, I will start to worry about whether I have been in contact with these cases and that I have been infected (P13)”. Another participant also stated, “The notice said that doctors and nurses working in the hospital are at risk of infecting their families. I am also worried that I have not taken effective preventive measures to spread the virus to my family. However, I am very homesick (P22)”. Doubt is defined as the feeling of distrust in the authenticity of information when healthcare professionals experience information anxiety. For example, “At that time, I felt that I began to doubt whether the information I saw on the Internet was true or false (P6)”. Another participant also stated, “When everyone doesn't know much about this virus, I suspect that many sudden messages are false (P17)”. Caution is defined as the psychological changes that healthcare professionals had improved their awareness of protection when they experienced information anxiety. For example, “At the beginning of the epidemic, I didn't think it was a severe disease. But when I realized the outbreak began, I felt I needed stronger protection, according to the official information (P21)”. Another participant also stated, “I realized that I need to protect myself from infection at work (P23)”. Hope is defined as the psychological changes that healthcare professionals expect to live an everyday life when they experienced information anxiety. For example, “I feel that this place is suddenly quiet. I still miss the prosperous time in the past (P11)”. Another participant also stated, “After returning to work and production, I wonder when I can return to normal life (P13)”.

Psychological signs of front-line healthcare professionals in information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic are expressed as their intuitive feelings about the epidemic and virus news when they search, browse, judge and use information. According to the above statements of the participants, the less healthcare professionals understand the virus information, the more obvious their psychological signs of information anxiety will be.

3.1.2 Physical signs

Physical signs are adverse physical changes of front-line healthcare professionals caused by information anxiety, which includes four subcategories: insomnia, inattention, memory loss and appetite decreased.

Insomnia is defined as the difficulty of falling asleep caused by information anxiety. For example, “I have been very nervous reading messages on my phone until 2 or 3 o'clock, and I basically lose sleep (P7)”. Inattention is the physical sign of difficulty concentrating at medical work or in life due to information anxiety. For example, “When I see epidemic news, my attention will be distracted (P7)”. Memory loss is defined as memory declined caused by information anxiety. For example, “I occasionally experience memory loss (P7)”. Appetite decreased is defined as being busy with medical work and not having time to think about eating caused by information anxiety. For example, “I will have the feeling of not thinking about eating (P16)”.

Physical signs of front-line healthcare professionals with information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic often appear when they are eager to obtain specific information to complete the information task but fail to achieve it. In addition, only a few front-line healthcare professionals have suffered from insomnia, inattention, memory loss and appetite decreased caused by information anxiety in the interviews. Some healthcare professionals said that although they experienced information anxiety, it was not severe enough to show physical signs.

3.1.3 Behavioural signs

Behavioural signs are the abnormal behaviours of front-line healthcare professionals caused by information anxiety. These include four subcategories: panic buying of goods, be at a loss, pay attention to relevant information and change habits.

Panic buying of goods is defined as the behaviour of front-line healthcare professionals purchasing materials due to information anxiety. For example, “Seeing the news that supplies were snapped up, I went to stock up some food (P14)”. Another participant also stated, “Panic to buy expensive masks (P6)”. Be at a loss is defined as an act of not knowing what to do due to information anxiety. For example, “Every day in the clinical diagnosis, I don't know how to deal with this epidemic (P16)”. Another participant also stated, “At this time, I don't know how to deal with it (P9)”. Pay attention to relevant information is defined as the behaviour of front-line healthcare professionals searching for information and paying attention to epidemic news because of information anxiety. For example, “As soon as I open my phone, I see many new cases or new positive patients around (P17)”. Another participant also stated, “We pay attention to these data and the progress of the epidemic daily (P20)”. Change habits is defined as the behaviour of front-line healthcare professionals changing their searching habits due to information anxiety. For example, “I avoid letting myself read some news on the Internet (P8)”. Another participant also stated, “It used to be a very relaxed state to look at the mobile phone. But now I reduce the time of browsing information (P9)”.

Behavioural signs of front-line healthcare professionals in information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic often appear when they want to relieve anxiety. Therefore, behavioural signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety are mostly targeted, which change according to the causes of information anxiety.

3.2 Signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety in different periods of the COVID-19 pandemic

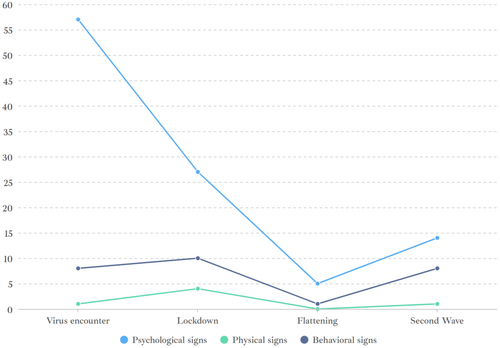

According to the frequency and frequency variation of psychological, physical and behavioural signs in various periods of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2 shows the sum of signs in four periods), the trends of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety signs could be drawn, as shown in Figure 3.

As seen in Figure 3, psychological signs were the most in every pandemic period according to the frequency of signs. The statements of front-line healthcare professionals can explain this phenomenon. During the virus encounter, a participant stated, “If you don't understand COVID-19 at all, you will have a certain fear (P4)”. During lockdown, another participant stated, “It's a nervous mood to see these messages every day, so everyone seems a little unnatural (P21)”. During flattening, a participant stated, “After returning to work, I hope to return to normal life (P13)”. During second wave, a participant stated, “But in recent days, there are always sporadic local cases, which is still a little worried (P20)”. There are differences in psychological signs of information anxiety during different periods of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The frequency variation of psychological, physical and behavioural signs in four periods shows different characteristics. Firstly, it can be seen from the figure that psychological signs are the most obvious, and the behavioural and physical signs are not obvious during the virus encounter because participants said they were prepared for such public health emergencies but did not realize the severe consequences of the virus. Secondly, psychological signs decreased, and the behavioural and physical signs suddenly increased during lockdown. Most front-line healthcare professionals began searching for information about the epidemic and were eager to buy medical and emergency supplies. If the anxiety is not eliminated with the behaviour, they will show physical signs. Thirdly, all signs decreased during flattening. For example, a participant stated, “In the meantime, the epidemic has disappeared, so I don't feel anything special. I thought this matter might finally end (P24)”. Another participant also stated, “Knowing that there were no new cases, I became happy (P9)”. Finally, all signs increased during second wave. Participants stated that they were afraid and worried about the epidemic because of the rebound of the epidemic (P20). And they paid more attention to the new number of epidemic cases (P18).

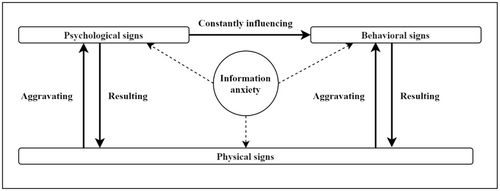

3.3 Grounded theory conceptual model during the COVID-19 pandemic

Twenty-four interviews of front-line healthcare professionals were used to construct conceptual models. Axial coding results in different periods were used to identify the relationships between the core categories. To explore the relationships between the core categories, the interviews were reviewed, and those signs that were conceptually related to each other based on the statements of the participants were extracted, as shown in Figure 4.

Conceptual models only appeared during virus encounter and lockdown, in which the subcategories were conceptually related to each other. However, the frequency of physical signs was not enough to construct a model in the flattening, while signs were relatively independent, and there was no conceptual correlation, so it was not enough to construct a model either. Therefore, there is no obvious correlation between the signs during flattening and second Wave.

Psychological signs constantly influence behavioural signs. Most front-line healthcare professionals said they hoped that some behaviours could alleviate their psychological difficulties because of fear and tension. For example, a participant stated, “I am very anxious about the epidemic information (psychological sign). The first thing I open my eyes every morning is to check Weibo (behavioral sign), hoping to get some good news (P11)”. Due to the lack of understanding of the virus, most participants, under the constant influence of psychological signs, were eager to make up for the gap between themselves and knowledge or did not know how to make up.

Severe psychological and behavioural signs are associated with physical signs. On the one hand, psychological and behavioural signs result in physical signs. For example, a participant stated, “Paying attention to the epidemic news (behavioral sign) until two or three o'clock in the morning, and I will lose sleep (physical sign) (P7)”. Another participant also said, “If I don't know the situation (behavioral sign), I will not think about eating (physical sign) (P16)”. On the other hand, physical signs aggravate psychological and behavioural signs. For example, a participant stated, “We still suffer from insomnia occasionally (physical sign) because we need to continue to support the community. And we need to wait for the information. We need to wait for the prevention and control headquarters to notify our hospital, so we are particularly anxious (psychological sign) while waiting for information (P7)”. Another participant also stated, “I don't want to eat (physical sign). Then the epidemic information continues to affect my life, so I can only divert my attention more (behavioral sign) (P16)”.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Information anxiety signs

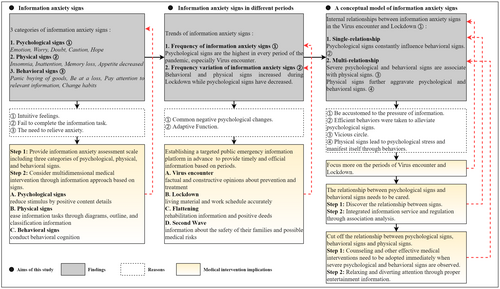

The study explored signs of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Wuhan hospital. Then, it was found that the periods of virus encounter, lockdown, flattening and second wave impacted information anxiety signs. Subsequently, a conceptual model of healthcare professionals' information anxiety signs was conducted. Here are several main contributions of this study:

First, three categories of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety signs during the COVID-19 pandemic were found, including five subcategories of psychological signs (emotion, worry, doubt, caution and hope), four subcategories of physical signs (insomnia, inattention, memory loss and appetite decreased) and four subcategories of behavioural signs (panic buying of goods, be at a loss, pay attention to relevant information and change habits), which extended existing dimensions of information anxiety sign. Several studies indicated that information anxiety signs could be described as fear, worry, anxiety and other psychological signs (Naveed & Ameen, 2017; Wurman, 2000; Xiang et al., 2021), while accurate classification and comprehensive analysis of information anxiety signs were also not emphasized in existing studies. In addition to psychological signs, anxiety signs generally include smoking, alcohol abuse, inattention and other behavioural or physical signs (Duko et al., 2022). By comparing the signs of information anxiety and anxiety, anxiety signs are more complex and extreme according to the studies, so it is worth targeted analysis and treatment for a specific sign or symptom, but information anxiety signs are more multidimensional, so it is suggested to consider multidimensional medical intervention, especially the corresponding information approaches.

Second, studies explained the effect of various periods of the COVID-19 pandemic on the signs of information anxiety according to the frequency of signs. The findings revealed that psychological signs were the most in every period of the pandemic, especially virus encounter. The reason is that healthcare professionals will have common negative psychological changes in the face of a large number of false and frightening news based on their statements. However, they have a lot of knowledge and experience in dealing with public health emergencies, which has been confirmed (Cankurtaran et al., 2021). It means that psychological signs of information anxiety are the most noteworthy issue among healthcare professionals.

The trends of psychological, physical and behavioural signs in various periods had characteristics according to the frequency variation of signs. Particularly, behavioural and physical signs increased during the lockdown while psychological signs decreased, which showed an adaptive function of healthcare professionals (Bowlby, 1973). The reason is that information anxiety during virus encounter has brought specific psychological preparation to healthcare professionals. Even if they face a severe impact during the lockdown, their psychological signs of information anxiety will not increase. Many studies have confirmed that the early period of COVID-19 was more likely to lead to psychological problems such as anxiety (Hawes et al., 2021; Shevlin et al., 2020). However, there are obvious differences in information anxiety signs at different periods of the COVID-19 pandemic in this study. Psychological signs were very obvious in every period of the pandemic and generally changed with the severity of the pandemic; Physical signs were not obvious in every period of the pandemic, which would only appear when the pandemic situation was grim; Behavioural signs were obvious in every period of the pandemic, but the behaviour sign in every period of the pandemic was different. For example, healthcare professionals tended to search for information excessively during the virus encounter and lockdown, while they tended to avoid information notification in the second wave. Therefore, it is necessary to determine information approaches according to the trends of signs in various periods.

Third, although there are three categories of information anxiety signs during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a certain internal relationship between them in the virus encounter and lockdown. However, there is no internal relationship between information anxiety signs in the flattening and second Wave. The reason is that healthcare professionals have been accustomed to the pressure of information search and information inquiry brought by the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, information anxiety signs are unclear, and the relationships between the signs are weakened. Therefore, medical interventions should focus more on the periods of virus encounter and lockdown.

On the one hand, psychological signs constantly influence behavioural signs. The reason is that front-line healthcare professionals will take efficient behaviours to alleviate psychological signs and avoid incalculable medical and social risks. The relationship between psychological and behavioural signs is reaffirmed by many studies on anxiety and information anxiety. For example, Piccirillo et al. stated that safety behaviours are typically employed by socially anxious individuals to reduce anxiety in feared social situations. It means that people in different situations will take types of behavioural measures to deal with psychological signs such as anxiety and fear. Therefore, the relationship between the psychological and behavioural signs of front-line healthcare professionals needs to be cared for during the epidemic.

On the other hand, severe psychological and behavioural signs are associated with physical signs. The reason is that physical signs of healthcare professionals often occur after work when the information they get in a day's work has reached the limit. At this time, they have no time and energy to take action to alleviate anxiety, so physical signs often occur and affect the work and life of the next day, causing a vicious circle. In addition, physical signs further aggravate psychological and behavioural signs. The reason is that physical signs affect the medical and nursing work of healthcare professionals in public health emergencies, further leading to psychological stress and manifesting itself through behaviours. Obviously, it requires taking information approaches to cut off the relationship between psychological, behavioural and physical signs and pay attention to the retroaction of physical signs to psychological and behavioural signs.

4.2 Implications for medical intervention of information anxiety

The analysis of information anxiety signs was essential for understanding the information anxiety of front-line healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic and providing evidence for medical institutions to trigger immediate and effective medical intervention through an information approach. In Figure 5, key findings of this study and their reasons, and suggested medical intervention through an information approach are presented as well.

First, psychological, physical and behavioural signs should be included in the scope of assessing information anxiety levels by medical institutions and governments, and 13 subcategories are used as secondary assessment indicators. At present, psychological assessment research involves multidimensional items, which mostly adopt methods of self-reported, questionnaires and interviews. Then, ambulatory assessment or ecological momentary assessment enjoyed enthusiastic implementation in psychological research (Wright & Zimmermann, 2019), which confirmed the feasibility and necessity of long-term psychological assessment. Although Zung's self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) and its related improved scales have been widely used in anxiety disorder screening (Dunstan & Scott, 2020), whether it can be applied to information anxiety assessment needs further research. Therefore, it is necessary to design an information anxiety scale (IAS) of psychological, behavioural and physical signs to enhance the practical knowledge for efficiently dealing with information anxiety related to front-line healthcare professionals. Based on the results of IAS, if information anxiety signs are within the normal range, assessment results of information anxiety need to be recorded and archived. If not, medical interventions need to be adopted according to their assessment level of information anxiety.

On this basis, multidimensional medical intervention through an information approach should be considered based on signs. In terms of psychological signs, medical institutions should help healthcare professionals reduce stimulus by positive content details (Hallford et al., 2022) during the pandemic and avoid negative emotional reactions. In terms of physical signs, healthcare professionals are often multi-tasked and are constantly impacted by a large number of fragmented information in the process of completing the task, which leads to continuous partial attention (Saxena et al., 2017). When the task is difficult to complete, they often have physical signs. It is necessary to ease information tasks through diagrams, outlines and classification information (Zhang et al., 2017) to avoid information overload. In terms of behavioural signs, it is suggested to conduct behavioural cognition (Fernandez-Alvarez & Fernandez-Alvarez, 2019) when necessary to make healthcare professionals understand their excessive behaviours and adjust themselves.

Second, actively and purposefully alleviating information anxiety during different periods is suggested. A targeted public emergency information platform could be established in advance to provide timely and official information that front-line healthcare professionals are concerned about according to the periods of a pandemic. For example, providing factual and constructive opinions about prevention and treatment for healthcare professionals to assist medical work during virus encounter, providing information on living materials and work schedules accurately to support their daily life during lockdown, providing rehabilitation information and positive deeds make healthcare professionals maintain a good attitude during flattening and providing information about the safety of their families and possible medical risks to reduce panic during second wave.

Third, the relationship between psychological signs and behavioural signs of front-line healthcare professionals needs to be cared for. Information research methods such as questionnaires and interviews can be used to obtain the causes of signs so as to discover the relationship between signs according to the analysis results. Once it is found that psychological signs are affecting behavioural signs, it is necessary to take psychosocial support, adaptive emotion regulation and tailoring mental health interventions (Asmundson et al., 2020; Breidenbach et al., 2022) to provide integrated information service and regulation on psychological signs and behavioural signs through association analysis.

Furthermore, the relationship is cut off among psychological, behavioural and physical signs. Existing studies have been conducted in proposing medical interventions for single signs but have ignored the relationship between different signs of information anxiety. Hence, counselling and other effective medical interventions need to be adopted immediately when serious psychological and behavioural signs are observed so as to ensure the regular operation of medical institutions during public health emergencies. Then, it is worth relaxing and diverting attention through proper entertainment information (Hwang & Borah, 2022) and physical activity (Marconcin et al., 2022) during the rest time so as to keep their physical health and prevent more severe psychological and behavioural signs.

This study has theoretical and practical strengths. From the perspective of theoretical strengths, the study considers the phenomenon of information anxiety among front-line healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic, and accurately classifies and comprehensively analyses the categories of information anxiety signs. This deepens the research on the mental health of front-line healthcare professionals during public health emergencies, and expands the research dimensions and contexts of information anxiety. From the perspective of practical strengths, this study proposes intervention through information approaches, providing suggestions for maintaining the health of healthcare professionals, thereby helping medical institutions operate efficiently and orderly and further providing practical experience for future response to public health emergencies.

There are also limitations. This study adopts the steps of semi-structured interviews and programmatic grounded theory to identify the information anxiety signs of front-line healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic and the relationship between signs. In the process of data collection and analysis, the researcher's understanding of information anxiety is integrated. Further quantitative research can be carried out to understand and modify the conceptual model of information anxiety signs.

5 CONCLUSION

In order to explore information anxiety signs of front-line healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic, 24 front-line healthcare professionals who worked in a Wuhan hospital during the pandemic were recruited to participate in semi-structured interviews, and the data obtained were used for subsequent grounded theory analysis. The results of the present study showed that 13 subcategories of front-line healthcare professionals' information anxiety signs during the COVID-19 pandemic could be classified into three categories: psychological, physical and behavioural signs. Psychological signs were the most common in the four periods of the pandemic according to the frequency of signs. Psychological signs decreased significantly, while behavioural and physical signs increased during the lockdown according to the frequency variation of signs. Then, all signs decreased during flattening and increased during second wave. According to the summary, a conceptual model consisting of psychological, physical and behavioural signs could be constructed. The results help to understand the information anxiety of front-line healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic and urge medical institutions and governments to trigger effective medical interventions through an information approach to maintain the mental and physical health of front-line healthcare professionals so as to promote the normal operation of medical institutions in public health emergencies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Quan Lu: Conceptualization, formulation or evolution of overarching research goals and aims. Liang Tao: Resources, provision of study materials, patients and other analysis tools. Xueying Peng: Writing, preparation, creation and presentation of the published work, specifically writing the initial draft (including substantive translation). Jing Chen: Supervision, oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (No: 20ATQ008).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no known competing interests, financial interests or other relationships that could appear to influence the article.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Our study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Wuhan University (approval no. IRB2022012). All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the participant's requirements but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.