Negative association between workplace violence and patient safety behaviour in male, but not female, nursing interns: A cross-section study

Abstract

Aim

The aim of the study was to compare the associations between workplace violence and patient safety behaviour between male and female nursing interns.

Design

A cross-sectional survey.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was carried out at three general hospitals in Shandong Province in China to collect data from 466 nursing interns. We evaluated the associations between workplace violence and patient safety behaviours in men and women using multiple linear regressions.

Results

Sex moderated the association between workplace violence and patient safety behaviour (B = 1.046, [SE = 0.477]; p = 0.029). Among male nursing interns, there was a significant association between workplace violence and patient safety (B = −1.353, 95% CI [−2.556, −0.151]; p = 0.028). In male nursing interns, verbal violence and sexual violence were significantly negatively associated with patient safety (B = −1.569, SE = 0.492, p = 0.002; B = −45.663, SE = 5.554, p < 0.001). No significant association was found in female nursing interns.

Patient or Public Contribution

This study did not have a patient or public contribution.

1 INTRODUCTION

Patient safety incidents are recognized as the leading cause of hospital morbidity and mortality worldwide (Liu et al., 2019). According to (World Health Organization [WHO], 2018a, 2018b), approximately 43 million patients suffer injury or death yearly due to patient safety incidents; patients face a 1 in 10 chance of being harmed during hospitalization. Nursing interns refer to nursing students who have completed the theoretical courses and then go to an affiliated hospital for 8- to 10-month clinical practice in their senior years (Liu et al., 2021). Clinical nursing practice is a vital process of nursing interns' transition from theoretical learning to clinical practice, where interns begin to face various patients and carry out clinical nursing operations in a hospital environment (Wang et al., 2021). Nursing interns are primary hands-on caregivers of hospitalized patients and play an important role in patient safety and high-quality care delivery (Song & Guo, 2019). However, nursing interns are unfamiliar with the ward environment and have not developed mature knowledge and skills to deliver safe care; both limitations may pose safety hazards such as medication errors, infection and falls (Gorgich et al., 2016; Stevanin et al., 2015). Nursing interns cause approximately 17%–53.2% of patient incidents during clinical learning experiences (Stevanin et al., 2018). Other studies have indicated that patient incidents can lead to additional hospitalizations, medical costs, infections acquired in hospitals and low healthcare efficiency (Song & Guo, 2019). Some studies have reported that the health costs associated with unsafe practices are estimated at $19 billion annually (WHO, 2017).

Patient safety behaviour is a valuable predictor for decreasing patient incidents (Brasaitė et al., 2016). Patient safety-related behaviours refer to non-technical and behavioural skills for enhancing safe delivery while caring for patients. These behaviours include communication, vigilance and decision-making (Brasaitė et al., 2016; Yilmaz et al., 2020). Exploring the factors influencing patient safety behaviour in nursing interns may provide a new avenue for identifying the risk factors and carrying out targeted interventions to prevent the onset of patient incidents in healthcare systems.

Among the numerous factors that influence patient safety behaviours in medical staff, workplace violence has gradually aroused the interest of researchers. Workplace violence is defined as incidents where staff are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances linked to their work (WHO, 2018a, 2018b). This includes verbal abuse or threats, physical assault and sexual harassment (Al-Qadi, 2021). Workplace violence is a widely reported phenomenon among nursing interns, with a high prevalence. For example, one study surveyed 657 nursing interns; nearly 50% reported experiencing harassment or bullying in the past year (Tee et al., 2016). Another cross-sectional study indicated that the prevalence of clinical violence against nursing interns was 37.3% (Cheung et al., 2019).

Affective events theory (AET) suggests that emotional, attitudinal and behavioural reactions are influenced by events in the workplace and resulting affective states (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). The core idea of AET is that one's affective response to workplace events largely determines one's attitudes and subsequent behaviours (Carlson et al., 2011). According to the AET and empirical research, workplace violence could elicit negative nurse outcomes, such as hindering the utilization of patient safety behaviours (Li et al., 2020). Some studies have recently investigated the association between workplace violence and patient safety behaviours, but their conclusions have been inconsistent. For instance, Chen and Kong (2018) surveyed 105 male nurses and found that loneliness and unsafe healthcare behaviour were linked to high levels of workplace violence. However, other studies found no such association. For example, Laschinger (2014) surveyed 336 nurses from acute care settings and showed that bullying and incivility from nurses, physicians and supervisors did not directly affect the quality of patient care.

Some scholars have begun to examine whether gender differences contribute to variability in the relationship between workplace violence and patient safety behaviours. Nursing is a female-dominated profession, and in some cultures, nursing is considered a career more suited to women. The number of male nurses in recent years has gradually increased, especially given the global nursing shortage. According to the National Health Commission (2021), in China, the number of registered Chinese male nurses has reached 125 thousand, which may significantly impact the care of patients. Social role theory posits that men and women rate and respond to stressful events differently based on their different social roles (Eagly & Wood, 1999). Few studies have explored gender differences in the association between workplace violence and patient safety behaviours. Li et al. (2020) conducted a secondary analysis of cross-sectional survey data and found that, compared with female nurses, male nurses experienced more workplace violence. In addition to responding emotionally to workplace violence, male nurses respond behaviourally. In this study, the nurses were evaluated based on burnout, job satisfaction and intention to stay in the field. There were, however, several problems with this study. First, the study was conducted among nursing and non-nursing interns, and the sex-stratified associations between workplace violence and patient safety behaviours were not assessed among nursing interns. Second, measuring nursing outcomes neglected patient safety behaviours. Identifying sex-specific workplace violence predictive factors for patient safety behaviour could improve our understanding of the potential mechanisms involved in the relationship between workplace violence and patient safety behaviours in male and female nursing interns and help nursing managers employ more effective intervention strategies. Therefore, the current study aimed to perform a sex-stratified examination of the associations between workplace violence and patient safety behaviour among nursing interns.

Different dimensions of workplace violence may play varying roles in the unsafe delivery of patient care (Kim et al., 2021). As mentioned above, workplace violence can be divided into verbal, physical and sexual violence. Previous studies have revealed that male nurses are different from female nurses in terms of exposure to workplace violence (Edward et al., 2016). A systematic review of 2042 nurses reported that male nurses were at a higher risk of experiencing physical violence, and female nurses were at a higher risk of verbal violence (Edward et al., 2016). Despite the findings of previous studies, relatively few have discussed how different types of workplace violence impacts patient safety behaviours. Thus, this study's second aim was to explore the role of verbal, physical and sexual violence in patient safety behaviour in nursing interns.

2 METHODS

We performed a cross-sectional study from October to December 2021 on 466 nursing interns. The sampling of nursing interns was conducted based on the convenience sampling method from three general hospitals in Shandong Province, China. These nursing interns met the following study criteria: (1) aged ≥18 years; (2) participating in an internship for more than 6 months; and (3) volunteering for the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) internship of fewer than 6 months; (2) failure to complete the planned hospital internship; (3) inability to fill in the questionnaire; and (4) unwillingness to participate.

2.1 Ethics statement

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Liaocheng People's Hospital before data collection. The study's attributes, benefits, uses and disadvantages were explained to all participants, and informed consent was obtained.

2.2 Data collection

We used Wenjuanxing, a web-based survey tool, to collect data. Initially, we acquired the administrative assistance of the nursing department. Then, we asked the administrative staff who responded to managing nursing interns to post the survey link on their WeChat and QQ contact networks. We introduced the purpose of the survey to the nursing interns on the first page of the questionnaire, and the questionnaire was filled out by nursing interns voluntarily. To ensure the integrity of the data, all entries were set to ‘required questions’. The anonymous self-report structured electronic questionnaires included a demographic information scale, a Chinese version of the workplace violence scale (WVS) and a Patient Safety Behaviour Scale (PSBS).

2.3 Measurements

2.3.1 Demographic characteristics

The demographic information scale comprised questions regarding sociodemographic variables, including age, sex (male/female), ethnicity (Han/others), location (urban or rural), the only child in the family (Yes/No), class officer (Yes/No), level of education (junior college/undergraduate), healthcare workers among family members (Yes/No) and internship time.

2.3.2 Workplace violence

We chose the Chinese version of the WVS to assess the prevalence of workplace violence among nursing interns. The scale was developed by Li (2019) based on the WHO's definition of workplace violence. The WVS aimed to investigate the experiences of workplace violence in nursing interns in the past 6 months. It contains three dimensions (verbal violence, physical violence and sexual violence) and six items. Verbal violence refers to the language used as an assault on another person's ego (e.g. scolding, verbal abuse, verbal threats, insults or belittling; Infante & Wigley, 1986). Physical violence refers to using physical force against others (e.g. slapping, biting, kicking or pinching). Sexual violence refers to any unwanted behaviours or words of a sexual nature (e.g. sexual harassment or sexual assault). Each item is answered on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 4 (1 = 0 time, 2 = 1 time, 3 = 2–3 times, 4 = ≥4 times). The total score is the sum of the six items, and the higher the possible score, the higher the frequency of workplace violence to which the respondent was subjected. The Chinese of the WVS was verified to be reliable, with Cronbach's α of 0.876 (Li, 2019). In the current study, Cronbach's α for the WVS was 0.802.

2.3.3 Patient safety behaviour

The PSBS, developed by Shih et al. (2008), was used to examine the frequency of these patient safety-related adverse events in nursing students. The PSBS consisted of 12 items: collaboration, washing hands, familiarity with standard workflow, aseptic technique and adjusting mental and physical strength. Each item is scored from 1 to 5 (1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = most, 5 = always), with a higher score reflecting a higher level of patient safety-related behaviour. An example item was: ‘when involved in any patient treatment or care activities, I always take the initiative to identify patients correctly’. Previous research confirmed the reliability of this scale, with Cronbach's α of 0.889 (Shih et al., 2008). Cronbach's α for the PSBS in the current study was 0.860.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp.). Means (standard deviations) were used to describe continuous variables, and frequency (percentage) was used for categorical variables. Independent t-tests, χ2 tests and the Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare the characteristics, WVS scores, and PSBS scores between male and female nursing students. We conducted univariate associations between demographic characteristics and patient safety behaviours for all participants and male and female nursing students separately. We analysed the interaction effect between workplace violence and sex on patient safety behaviour using multiple linear regression analyses of all participants. If the interaction was statistically significant, we conducted a linear regression analysis of workplace violence on patient safety behaviour, separately by sex. Finally, we performed a multiple linear regression analysis to distinguish the contributions of verbal, physical and sexual violence to patient safety. The significance level (two-tailed) was set at p < 0.05.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

Tables 1 and 2 show the demographic characteristics and scores on workplace violence and PSBS for the 466 nursing interns. Their mean age was 20.26 (SD = 1.07) years. The mean WVS score was 6.61 (1.42), and the mean PSBS score was 55.63 (5.39). Univariate analysis showed that female nursing interns were significantly younger (p = 0.018), had lower rates of living in urban (p = 0.020), had lower rates of were only children (p < 0.001), lower rates of were class officers (p < 0.001) and lower prevalence of threaten (p = 0.032) than male nursing interns.

| Variable | Total (n = 466) | Male (n = 77) | Female (n = 389) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean [SD]) | 20.26 (1.07) | 20.52 (1.22) | 20.21 (1.03) | 0.018 |

| Ethnic, Han (n [%]) | 461 (98.93) | 77 (100) | 384 (98.71) | 0.606 |

| Location, urban (n [%]) | 95 (20.39) | 23 (29.87) | 72 (18.51) | 0.020 |

| Only child in family, yes (n [%]) | 90 (19.31) | 33 (42.86) | 57 (14.65) | <0.001 |

| Class officer, yes (n [%]) | 149 (31.97) | 42 (54.55) | 107 (27.51) | <0.001 |

| Level of education, undergraduate (n [%]) | 57 (12.23) | 11 (14.29) | 46 (11.83) | 0.863 |

| Healthcare workers among family members, yes (n [%]) | 11 (2.36) | 4 (5.19) | 7 (1.80) | 0.091 |

| WVS score (mean [SD]) | 6.61 (1.42) | 6.70 (1.42) | 6.59 (1.42) | 0.516 |

| PSBS score (mean [SD]) | 55.63 (5.39) | 55.19 (7.35) | 55.71 (4.92) | 0.442 |

- Abbreviations: PSBS, Patient Safety Behaviour Scale; WVS, workplace violence scale.

| Dimensions of workplace violence | Never happened [n (%)] | Had happened [n (%)] | Z value | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 time | 2–3 times | ≥4 times | ||||

| Verbal violence | ||||||

| Scold, verbal abuse, insult or belittle | ||||||

| Male nursing interns (n = 77) | 58 (75.3) | 6 (7.8) | 6 (7.8) | 7 (9.1) | −0.07 | 0.944 |

| Female nursing interns (n = 389) | 286 (73.5) | 58 (14.9) | 34 (8.7) | 11 (2.8) | ||

| Threaten | ||||||

| Male nursing interns (n = 77) | 69 (89.6) | 4 (5.2) | 4 (5.2) | 0 (0) | −2.143 | 0.032 |

| Female nursing interns (n = 389) | 372 (95.6) | 10 (2.6) | 5 (1.3) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Physical violence | ||||||

| Slapping, biting, kicking or pinching | ||||||

| Male nursing interns (n = 77) | 76 (98.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | −0.158 | 0.874 |

| Female nursing interns (n = 389) | 383 (98.5) | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Coerce | ||||||

| Male nursing interns (n = 77) | 77 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | −0.445 | 0.656 |

| Female nursing interns (n = 389) | 388 (99.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Sexual violence | ||||||

| Sexual harassment or sexual advance | ||||||

| Male nursing interns (n = 77) | 77 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | −1.56 | 0.119 |

| Female nursing interns (n = 389) | 377 (96.9) | 7 (1.8) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | ||

| Sexual assault | ||||||

| Male nursing interns (n = 77) | 76 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | −0.005 | 0.996 |

| Female nursing interns (n = 389) | 384 (98.7) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) | ||

- Note: p-Value was derived from the Mann–Whitney U test.

3.2 Univariate analyses of associations between demographic characteristics and patient safety in all participants

Table 3 presents univariate analyses of the relationships between demographic characteristics and patient safety in all participants. The results revealed no significant associations between different demographic characteristics and patient safety scores in all participants. For men, no significant associations were observed between other demographic characteristics and patient safety scores. For women, increased patient safety behaviour scores were significantly associated with a lower level of education (F = 5.140, p = 0.005).

| Variables | Category | N (%) | Total score of patient safety, mean (SD) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic | Han | 461 (98.93) | 55.62 (5.41) | −0.156 | 0.876 |

| Others | 5 (1.07) | 56.00 (3.81) | |||

| Location | Urban | 95 (20.39) | 54.68 (7.66) | −1.915 | 0.056 |

| Rural | 371 (79.61) | 55.87 (4.62) | |||

| Only child in family | Yes | 90 (19.31) | 55.40 (6.48) | −0.444 | 0.658 |

| No | 376 (80.69) | 55.68 (5.10) | |||

| Class officer | Yes | 149 (31.97) | 56.11 (5.15) | 1.34 | 0.181 |

| No | 317 (68.03) | 55.40 (5.49) | |||

| Level of education | Junior College | 408 (87.55) | 55.79 (5.40) | 1.242 | 0.294 |

| Undergraduate | 58 (12.45) | 54.49 (5.31) | |||

| Healthcare workers among family members | Yes | 11 (2.36) | 55.82 (4.81) | 0.119 | 0.905 |

| No | 455 (97.64) | 55.62 (5.41) |

3.3 Workplace violence × sex interaction effects on patient safety

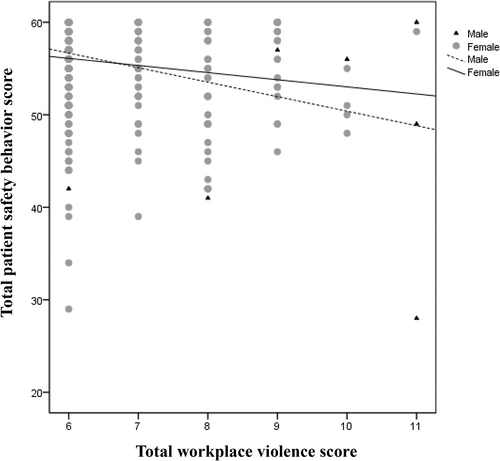

Scatterplots of the actual values of workplace violence and patient safety by sex showed that the linear associations between workplace violence and patient safety differed between male and female nursing interns (Figure 1). The results showed a significant effect of the interaction between workplace violence and sex on patient safety (B = 1.046, [SE = 0.477]; p = 0.029), as shown in Table 4.

| Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | ||||

| Sex | −6.432 | 3.259 | −12.836, −0.028 | 0.042 |

| Workplace violence | −2.400 | 0.893 | −4.155, −0.644 | 0.007 |

| Workplace violence × sex | 1.046 | 0.477 | 0.109, 1.984 | 0.029 |

- Abbreviation: B, unstandardized regression coefficients.

3.4 Associations between workplace violence and patient safety by sex

We conducted a linear regression analysis of workplace violence on patient safety among male and female nursing interns (Table 5). The results showed that in male nursing interns, there was a significant association between workplace violence and patient safety (B = −1.353, 95% CI [−2.556, −0.151]; p = 0.028). However, we did not observe a significant association between workplace violence and patient safety among female nursing interns.

| Variable | B [95%CI] | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||

| Workplace violence | −1.353 [−2.556, −0.151] | −2.242 | 0.028 |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.050 | |||

| F = 5.027 | |||

| Female | |||

| Workplace violence | −0.206 [−0.563, 0.152] | −1.132 | 0.258 |

| Level of education | −1.547 [−3.032, −0.063] | −2.050 | 0.041 |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.013 | |||

| F = 3.647 | |||

3.5 Multiple linear regression models to identify the contribution of different aspects of workplace violence to patient safety in male participants

Multiple linear regression models were used to distinguish the contribution of verbal, physical and sexual violence to the explained variance in patient safety, as shown in Table 6. In male nursing interns, verbal violence and sexual violence were significantly negatively associated with patient safety (B = −1.569, SE = 0.492, p = 0.002; B = −45.663, SE = 5.554, p < 0.001).

| Dependent variable: Patient safety | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | |||

| Constant | 145.515 | 12.581 | 11.567 | <0.001 | |

| Verbal violence | −1.569 | 0.492 | −0.274 | −3.191 | 0.002 |

| Physical violence | 2.806 | 2.894 | 0.083 | 0.970 | 0.335 |

| Sex violence | −45.663 | 5.554 | −0.677 | −8.222 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.487 | ||||

| F | 25.042 | ||||

- Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

4 DISCUSSION

The main goal of the current study was to examine whether a sex-stratified association existed between workplace violence and patient safety behaviour among nursing interns. Our results suggest that sex moderates these associations. Our results demonstrated that elevated workplace violence scores were associated with lower patient safety behaviour scores among male nursing interns. We did not find this association in female nursing interns. Our results are consistent with previous research that indicated that sex predicted students' caring behaviours (Laurella, 1997).

One possible explanation is a difference in social roles. According to the social role theory, the male trait is agentic (goal-achievement traits), and the female trait is communal (expressive traits) in value preferences (Eagly & Wood, 1999). Specifically speaking, males specialized in instrumental behaviours related to task accomplishment. Females, more than males, specialized in socioemotional behaviours related to group maintenance. In the face of stressors, men are easily provoked and prone to behavioural responses (Li et al., 2020). While women are prone to respond to emotional vulnerability (Atwater et al., 2016; Ye et al., 2018). Studies showed that workplace violence is an important stressor in nursing, and workplace violence could distract nurses from work, disrupt nursing interactions and lead to substandard care and errors (Wolf et al., 2017). Therefore, when exposed to workplace violence, male nursing interns were more likely to exhibit poor patient care behaviour; female nursing interns were more likely to exhibit poor moods.

Nevertheless, some research showed that women use social support coping strategies better than men. Social support is a kind of nursing competence because it can enhance resilience to stress, protect them against developing trauma-related behaviour problems and decrease the adverse effects of trauma-induced disorders (Caruso et al., 2016). Ross and Mirowsky (1989) found that women may disclose and perceive higher levels of social support than those reported by men. Women reportedly have a stronger affiliative style than that of men (i.e. a wider social network) as they require greater social support for coping with adverse events. Some studies have considered the potential role of social support as a positive predictor of nurses' competence, behaviours and self-efficacy (Caruso et al., 2017; Zaghini et al., 2016). Therefore, male nursing interns may experience workplace violence from patients; however, they are less likely to seek social support, which is associated with poor patient outcomes. However, it remains unclear whether social support mediates or modifies the relationship between workplace violence and patient safety behaviour; thus, further studies are needed.

Another possible explanation is sex segregation in the nursing workplace. Nursing has been viewed as a female-dominant profession since the Florence Nightingale era (Yi & Keogh, 2016). In some countries, nursing is considered a female-only career (Fernández-Feito et al., 2019; Zhang & Liu, 2015). Compared with women, working as a nurse is much less attractive to men, particularly in Chinese culture, where providing care is a woman's job. Compared with the turnover rate from 2010 to 2015 among female nurses (8.3%), the turnover rate for male nurses was higher (17.2%) (Yu, 2017). A large cross-sectional study revealed that the occupational identity score of male nursing interns was lower than that of female nursing interns (Wang, 2019). Moreover, some studies have shown that male nurses, as the minority, experience discrimination and are victimized by patients and colleagues (Drange & Karlsen, 2016; Eriksen & Einarsen, 2004). We hypothesized that an interaction between workplace violence and a low level of occupational identity might occur when male nursing interns act together to cause poor patient safety behaviour. Further quantitative and qualitative studies are required to increase the understanding of male nursing interns' perceptions of workplace violence and its related negative consequences for better prevention.

Our study showed that among male nursing interns, verbal violence and sexual violence were significantly negatively associated with patient safety. However, physical violence was not found to be associated with patient safety. Sex violence is an offensive behaviour of a sexual nature that may make informal and formal caregivers feel intimidated, humiliated or uncomfortable (International Labor Organisation, 2018). Previous studies also found that sexual violence can affect individuals in several ways, including mental and physical health, job satisfaction, and caring behaviours (Kahsay et al., 2020). In a study conducted in Australia, approximately 34% of male nurses reported having experienced one kind of sexual violence at the hospital (Cogin & Fish, 2009). Sexual violence experienced by male nurses can decrease the quality of care (Chang & Jeong, 2021). Our study verified this conclusion among male nursing interns. Verbal violence refers to the language used as an assault on another person's ego, causing the victim to feel that she or his sense of self has been damaged (Infante & Wigley, 1986). Budin et al. (2013) showed that nurses who experience verbal violence could negatively evaluate their work environment, leading to a deterioration in their quality of nursing and job satisfaction, which is consistent with our findings. Physical violence was not found to be associated with patient safety. This might be related to the low percentage of physical violence experienced by male nursing interns.

This study has some limitations that cannot be ignored. First, the data were cross-sectional, preventing conclusions regarding the association's causality and directionality between workplace violence and patient safety behaviour. Therefore, further longitudinal investigation is required. Second, the current study used a self-report questionnaire to measure the prevalence of workplace violence, which may introduce potential reporter bias due to nursing interns' acceptance of workplace violence as part of the clinical practice (Kennedy, 2005), and the ‘stigma of violence’—that is those who suffer from workplace violence could feel ashamed to report it (Hoff, 1992). Therefore, we emphasize the principle of anonymity in the collection of data. Third, the current study employed a convenience sample, which might affect the generalizability of the results to other populations of nursing interns; thus, replication in future research is warranted.

5 CONCLUSION

Our findings reveal sex-specific associations between workplace violence and patient safety behaviours among nursing interns. We observed that workplace violence was negatively associated with patient safety behaviours in male nursing interns but not females. In addition, the study showed that verbal violence and sexual violence were significantly negatively associated with patient safety in male nursing interns. However, physical violence was not found to be associated with patient safety. From a theoretical point of view, the results of our study add valuable information about the sex differences in the relationship between workplace violence and patient safety behaviours among nursing interns, which is a crucial step for better prevention and support for coping with workplace violence and create a healthy work environment to guarantee the high quality of care delivery. From a practical viewpoint, our findings may raise awareness among head nurses and policymakers to choose sex-based strategies for developing appropriate instruction programmes for nursing interns-such as, for male nursing interns, we could teach them how to avoid verbal and sexual violence effectively by conducting integrated workplace violence management intervention (Chang et al., 2022) and early psychological preventive intervention (Tarquinio et al., 2016).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Qianqian Yang and Linlin Yang contributed to study design. Chunling Yang, Yue Chen Xia Wu, and Li Liu collected the data. Qianqian Yang analysed the data, prepared the first draft and wrote the manuscript. Linlin Yang and Chunling Yang interpreted data for the work. All authors approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All the authors thank all the members who took part in this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There are no conflicts of interest involved in the current study.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Liaocheng People's hospital (2021098), before the data collection.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No external funding.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.