The optimal intervention for preventing physical restraints among older adults living in the nursing home: A systematic review

[Correction added on 27 April 2023 after first online publication: The corresponding author's affiliation has been updated in this version.]

Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of restraint reduction programs for nursing home care providers in enforcing physical restraint on residents and identify the best strategies for such programs.

Design

Systematic Review.

Methods

We searched for randomized controlled trials published until February 2021 for systematic review. The systematic review captured multifactorial interventions, education and consultation measures, including nursing home residents' and care providers' results. Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration criteria.

Results

In all seven trials, the interventions were led by a nurse specialist or unit leader and targeted at care providers. Five of the restraint reduction programs effectively reduced the rate of physical restraint use; two increased knowledge of restraint reduction for care providers; and one each promoted positive attitudes and behaviours. Duration of at least 6 weeks significantly improved the knowledge of care providers.

1 INTRODUCTION

In nursing homes, the use of physical restraints for older adults is common in many countries (Bellenger et al., 2017; Foebel et al., 2016; Kor et al., 2018). The rate of physical restraint use in nursing homes is 18.8%–51.5% abroad (Abraham et al., 2019; Foebel et al., 2016; Huizing et al., 2009) and 62%–74% in Taiwan (Huang et al., 2014; Huang & Li, 2009; Lan et al., 2017). Compared to other countries, there is a tendency for a higher physical restraint rate in Taiwan's long-term care facilities.

There are different but similar definitions of physical restraint. The International Consensus Statement defines physical restraint as “any action or procedure that prevents a person's free body movement to a position of choice and/or normal access to their body by the use of any method, attached or adjacent to a person's body that they cannot control or remove easily” (Bleijlevens et al., 2016). Physical restraint is any means of restricting individuals' movement that cannot be easily removed by individuals (Collins et al., 2009), or any appliance or device used to prevent physical movement (Said & Kautz, 2013), including the use of bed rails, chair restraint and torso restraint (Foebel et al., 2016). Restraint is defined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (2002) as any device, material or equipment that prevents a person's body from controlling itself or moving freely and efficiently, to prevent the person from moving freely to another chosen position or close to their own body. This includes using a restraint belt tied to a chair or bed, excluding bed rails (Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011). The Taiwan Long-Term Care Professional Association defines physical restraint as the process of using devices or equipment on residents to restrict their freedom to move around or approach their body in their environment. This includes using restraint straps, restraint undershirts, meal boards and gloves, excluding bed rails and medication use (Taiwan Long-Term Care Professional Association, 2012).

Physical restraint is a form of physical elder abuse and a violation of human rights (Ayalon et al., 2016; Gu et al., 2019). However, the use of restraint to protect the safety of the elders is widespread, for example, to prevent falls, avoid self-extubation or interference with therapy, prevent agitation or control disruptive behaviours, and protect residents or others' safety (Estévez-Guerra et al., 2017; Leahy-Warren et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the use of restraints does not prevent them from falling (Dikiciyan, 2012). Some studies (Ferrão et al., 2021; Kor et al., 2018) show that care providers' attitudes tend towards restraint, but the feelings are negative. Furthermore, although they are aware of the need for restraint, there is often a moral conflict; even if they are not sure whether to restrain, they tend to restrain. The complications that result from restraint are often physical dysfunction, disruptive behaviours and the need for care and assistance from others (Estévez-Guerra et al., 2017; Foebel et al., 2016).

The U.S. Federal Nursing Home regulations and practice guidelines are consistent in recommending that restraints should not be used (ANA, 2020; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Many scholars abroad have promoted restraint-free programs in long-term care facilities, including in-service education and research to improve care providers' knowledge or behaviour regarding restraint (Abraham et al., 2019; Kong et al., 2017; Testad et al., 2016). Several scholars have shown that improving care providers' knowledge and awareness of restraint makes the attitudes to physical restraints more positive and can reduce restraint use (Eskandari et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2017; Kor et al., 2018).

Muir-cochrane et al. (2014) revealed that not easily accessible alternatives and unfavourable work environments, facility policies and interpersonal relationships were the main factors influencing care providers to implement restraints. De Bellis et al. (2013) found that care providers were rarely aware of alternatives to physical restraints. Therefore, both Kong et al. (2017) and Schmidtke (2018) suggested using alternative methods to achieve restraint reduction goals. Laiho et al. (2013) indicated that care providers should remove restraints by observing case behaviour, assessing risk factors and selecting interventions during the decision-making process. In geriatric care settings, the use of restraints can be reduced by developing alternative strategies, improving care providers' knowledge and awareness of restraints, and adopting the proper attitudes towards restraints (De Bellis et al., 2013; Kor et al., 2018).

Interventions related to the reduction of elderly restraints have been recently implemented in nursing homes, including multifactorial interventions (Gulpers et al., 2012, 2013; Koczy et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2017), education and consultation (Huizing et al., 2009) or educational approaches alone (Testad et al., 2016), each with different outcome measures and effectiveness.

Möhler et al. (2012) used a systematic review of the effectiveness of prevention and reduction of physical restraints in long-term care for older adults. They searched the literature as of September 2009. The study showed that nurses' educational programs may not effectively reduce physical restraint use among older adults in long-term care. It was also unclear which educational components should be included in educational programs to reduce physical restraints. Lan et al. (2017) performed a systematic literature review and integrated analysis of the impact of educational interventions on the use of physical restraints in long-term care facilities. A search of the database as of January 2017 found that educational interventions reduced physical restraints. A longer duration of education led to less use of physical restraints. Brugnolli et al. (2020) conducted a systematic literature review and integrated analysis of the effectiveness of educational training or multifactorial interventions on the use of physical restraint in long-term care facilities. A search of the database as of September 2019 found that educational programs and other complementary interventions effectively reduced the use of restraints and that longer interventions resulted in less use of physical restraints. In the three systematic reviews of the literature, the findings differed in their focus on educational interventions. Educational programs may not effectively reduce physical restraint. The outcome indicators focused only on the residents' effectiveness (physical restraint rate), without further elaboration on the impact of different interventions on care providers and residents. However, the effectiveness of physical restraint reduction strategies for nursing home residents and care providers is inconclusive. Therefore, there is a lack of inclusion of the effectiveness of various interventions on care providers and residents and a lack of identification of the best intervention strategies for restraint reduction programs.

2 AIMS

This systematic literature review aimed to explore the effectiveness of various interventions on care providers and residents and to identify the best intervention strategies for restraint reduction programs. Hopefully, the results of this study can be used as a reference for long-term care and related research.

3 DESIGN

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021) to conduct our systematic literature review (Appendix S1). Note that PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (For more information, see: www.prisma-statement.org). Given the nature of the study, no ethical issues were at need to be addressed.

4 METHODS

4.1 Search strategy

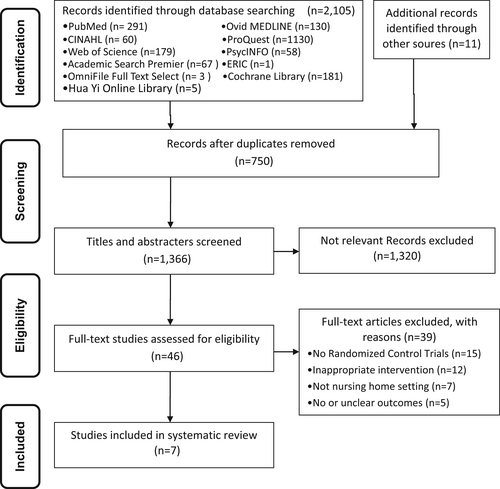

A literature review was conducted to search for literature published in electronic databases PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, ProQuest, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, ERIC, OmniFile Full Text Select, Cochrane Library and Hua Yi Online Library that met the inclusion criteria as of February 2021 (Appendix S2). The key words set were restraint, physical restraint, belt restraint, elderly, reduced physical restraint, multifactorial intervention, education, consultation, nursing home and care provider. In this study, we focused on Chinese and English literature. Systematic reviews were manually checked to distinguish the related studies missed by electronic databases search (Figure 1).

4.2 Inclusion criteria

4.2.1 Types of studies

RCTs with restraint reduction programs as interventions in English and Chinese were used to examine the effectiveness of the restraint reduction programs on older adults' physical restraint in nursing homes. Literature reviews, case reports, retrospective literature and non-English and Chinese literature were excluded.

4.2.2 Types of participants

The study populations were care providers and elderly residents in nursing homes.

4.2.3 Types of interventions

Interventions consist of multi-factor interventions (policies to promote facilities to reduce the use of restraints, education, consultation and development of alternatives), education and consultation, and education or consultation alone.

4.2.4 Types of outcome measures

Based on the selected literature, the outcome measures selected to reduce restraints included the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of care providers in implementing physical restraints to residents, and the physical restraints of residents (restraint rate, restraint type, multiple restraint rate, agitation rate, extubation rate, fall rate and level of injury, and use of psychotropic drugs).

4.3 Search outcomes

We initially searched 2116 studies and deleted 750 duplicate files. After reviewing the title and abstracts of 1366 articles, we selected 46 articles for full-text review. Finally, we determined that seven studies matched the inclusion criteria. The other 39 trials were excluded with reasons documented in Figure 1.

4.3.1 Quality assessment and critical appraisal

A systematic literature review was conducted using a literature search strategy to gain relevant topics and abstracts. Two independent reviewers trained in evidence-based nursing individually assessed each study design's quality according to the Cochrane criteria provided by the Cochrane Collaboration (an evidence-based medical review group) and then confirmed the consistency between each other. In case of disagreement, a third independent reviewer was invited to reach a consensus.

4.3.2 Data extraction and data analysis

The two independent reviewers collected information. The same information collection form was used to collect information on the study design, several subjects, interventions and study results and check the consistency and accuracy. The data collection included the study population, the definition of physical restraint, restraint reduction interventions and outcome measures to understand the impact of restraint reduction. The evaluation results included the effectiveness of physical restraint implementation by care providers and the residents' physical restraint status.

5 RESULTS

Figure 1 shows the literature search and selection process of this study. Seven RCTs were finally selected for this study (Table 1).

| Types of intervention | Authors (year) | Participants | Intervention | Comparison | Losses to follow-up | Outcome measured | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational and consultation | Huizing et al. (2009) | 14 Dutch psychogeriatric nursing home wards (N = 241) |

8-month educational and consultation: 1. Educational program for nursing staff: (1) The intervention consisted of five 2-h educational sessions for selected staff delivered over 2 months, one 90-min plenary session for all staff, and consultation with a nurse specialist (RN level). (2) The educational program was designed to encourage nursing staff to adopt a restraint-free care philosophy and familiarize themselves with individualized care techniques. (3) Several topics concerning physical restraints, such as effectiveness, consequences, decision-making processes and strategies for analysing and responding to residents' risk behaviour, and real-life cases, were discussed in five training sessions of 2 h each. 2. Consultation with a nurse specialist (RN): (1) The nurse specialist was available from the start of the intervention until 8 months after the educational program's end for 28 consultation hours per week. (2) 1–4 h per week at each ward (n = 126) |

Usual care (n = 115) |

Loss: I: 48 (1 month: 25, 4 months: 14, 8 months: 9) C: 82 (1 month: 58, 4 months: 12, 8 months: 12) intention-to-treat analysis: NR |

Residents: 1. Restraint status 2. Restraint types 3. Restraint intensity 4. Multiple restraints |

There is no treatment effect on restraint status, restraint intensity or multiple restraint use in any three post-intervention measurements. |

| Educational | Pellfolk et al. (2010) | 40 group dwelling units for staff (n = 289) and people with dementia (n = 350) in Sweden |

6-month education program: 1. Participants: nursing staff (registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nurse's aides). 2. Before the program started, one volunteer from each unit attended the whole education program compressed into 2 days of seminars. 3. The remaining staff received their education in six 30-min videotaped lectures, one for each month. 4. Main Content of the Education Program: six different themes (1) Dementia (2) Delirium in older adults (3) Falls and fall prevention (4) Use of physical restraints (5) Caring for people with dementia (6) Complications in dementia [staff (n = 156) and residents (n = 185)] |

Usual care [staff (n = 133) and residents (n = 165)] |

Loss: I: 42 C:23 intention-to-treat analysis: YES |

Staff: 1. Knowledgea 2. Attitudes Residents: 1. Physical restraint usea 2. Number of falls 3. Psychoactive medication |

Staff: 1. The staff in the intervention group had more knowledge at follow-up than the staff in the control group (p < 0.05), but there were no intergroup differences about attitudes towards the use of physical restraints at follow-up (p = 0.09). 2. Analyses within the intervention group showed that staff attitudes had changed (p = 0.001) and that their estimated knowledge of dementia care had increased significantly (p < 0.001). Residents: 1. The widespread use of physical restraints decreased significantly in the intervention group between baseline and follow-up (p = 0.03), whereas it was unchanged in the control group (p = 0.08). 2. The intergroup analyses showed less use of restraints in the intervention group at follow-up than in the control group (p < 0.001). 3. There was no significant change in the number of falls or use of psychoactive medication. |

| Multicomponent intervention |

Koczy et al. (2011) Cluster-RCT |

Forty-five nursing homes in Germany (N = 333) |

3-month Multifactorial intervention: 1. One person responsible for the intervention from each participating home (change agent) was appointed. 2. They received one 6-hour mandatory training course. 3. Intervention: (1) Increasing Awareness (2) Education (3) Technical Aids (4) Problem-Solving Tools (5) Implementation of Course Contents (6) Support Intervention group (IG): n = 208 (23 nursing homes) |

Usual care (n = 125) (22 nursing homes) |

Loss: I: 60 C:37 intention-to-treat analysis: NR |

Residents: 1. Main outcome: physical restraint usea 2. Secondary outcomes: (1) Partial reductions in restraint usea (2) Percentage of fallersa (3) Number of psychoactive drugs (4) Behavioural symptoms |

1. Main outcome: After 3 months, the probability of being free of restraints was more than twice as high in the IG (16.8%) as in the CG (8.8%). 2. Secondary outcomes: (1) Reduced restraint use of at least 75%, 50%, or 25% was also achieved approximately twice as often in the IG as in the CG. (2) There was no significant increase in behavioural symptoms or medication. |

| Multicomponent intervention | Köpke et al. (2012) | 36 nursing homes clusters, German (N = 4449) |

6-month Multi-component interventions: 1. 90-min group sessions for all nursing staff: In addition to complete and concise versions of the guideline, the intervention provided information programs for all nursing staff 2. Additional training for nominated essential nurses: (1) education and structured support of essential nurses in each cluster (2) a one-day training workshop for nominated nurses 3. Supportive material for nurses, residents, relatives, and legal guardians (n = 2283) |

Received standard information (n = 2166) |

Loss: I:374 (3 months: 208, 6 months: 166) C:333 (3 months: 156, 6 months: 177) Intention-to-treat analysis: YES |

Residents: 1. Primary outcome: percentage of residents with physical restraintsa 2. Secondary outcomes: (1) Falls, fall-related fractures (2) Psychotropic drug prescriptions |

1. After 3 months, physical restraint prevalence was significantly lower in the intervention group, 23.9%, vs. 30.5% in the control group (p = 0.03). 2. After 6 months, physical restraint prevalence was significantly lower in the intervention group, 22.6%, vs. 29.1% in the control group (p = 0.03). 3. There were no statistically significant differences in falls, fall-related fractures, and psychotropic drug prescriptions. |

| Educational | Testad et al. (2016) | 24 nursing homes, Norway (N = 274) |

7-month training intervention “Trust Before Restraint”: 1. Phase 1: Involved education and coaching to support four teams of facilitators consisting of eight clinical research nurses, standardizing and adjusting the TFT intervention through discussions in groups, and role-playing the seven-step guidance group. 2. Phase 2: (1) Consisted of delivery of the intervention in 2–4 weeks commencing baseline data collection. (2) Similar to the RRC intervention, it consisted of a 2-day seminar (16 h) and followed by 1-h monthly seven-step guidance groups over 6 months. (3) The groups aimed to support nursing home staff in finding alternative solutions to the use of restraint and psychotropic drugs through teaching and coaching. (n = 118) |

Usual care (n = 156) |

Loss: I:33 C:40 intention-to-treat analysis: NR |

Residents: 1. Primary outcome: use of restrainta 2. Secondary outcome: (1) Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) (2) Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) (3) Use of psychotropic drugs |

1. Use of any restraint was statistically significantly reduced in both the intervention group (19.3% → 18.1%) and control group (18.4% → 8.8%) (p = 0.025; p < 0.001). 2. There was a significant reduction in CMAI score in both the intervention group (40.1 → 37.0) and the follow-up group (44.8 → 41.2) (p = 0.078). 3. Total NPI score increased in both groups, reaching significance in the treatment group (12.1 → 17.7) (p = 0.007). 4. Analysis of psychotropic drugs' use showed a slight nonsignificant increase in the use of antipsychotics (14.1–17.7%) and antidepressants (35.9–38.4%) in both groups over 7 months. |

| Multicomponent intervention | Kong et al. (2017) | nursing staff in two Korean nursing homes (N = 122) |

6-week MRRP: 1. Three educational sessions (two classroom-based and one web-based): (1) Session 1: 40-min educational session. Session 1 was repeated once in the same week to assure that all EG participants could attend. (2) Session 2: a self-directed web-based program for the reduction of physical restraint. The 54.33-min program targets nursing home staff and consists of six video modules. EG participants were invited to visit the website at any time over 2 weeks using computers in the nursing homes or their own homes. (3) Session 3: 40-min educational session, the primary investigator shared success stories about physical restraint reduction using a DVD. EG participants were asked to discuss their own experience with barriers to and strategies for restraint reduction. 2. Two unit-based consultations: After the conclusion of the three educational sessions, unit-based consultation was provided for selected EG staff in two separate 1-hour sessions over 2 weeks by two of the gerontological nurse authors. (n = 62) |

Usual care (n = 60) |

Loss: I: 4 C: 0 intention-to-treat analysis: NR |

Staff: 1. Knowledgea 2. Perceptionsa 3. Attitudesa |

The MRRP in the EG resulted in greater improvement in knowledge (p < 0.001), perceptions (p < 0.001), and attitudes (p = 0.011) about restraint compared with the CG |

| Multicomponent intervention | Abraham et al. (2019) | 120 nursing homes in four regions in Germany (N = 12,245) |

3-month Multi-component intervention: Intervention 1: an updated version of a successfully tested guideline-based multi-component intervention (comprising brief education for the nursing staff, intensive training of nominated essential nurses in each cluster, the introduction of a least-restraint policy, and supportive material) Intervention 2: Concise version of the original program (concise version, comprising the intensive training for essential nurses, the organizational component and all supplemental materials.) intervention groups 1 (n = 4126) Intervention groups (n = 3547) |

Optimized usual care (supportive materials only) (n = 4572) |

Loss: I:1127 (6 months): 536 12 months: 591 C:1251 (6 months: 581, 12 months: 670) Intention-to-treat analysis: YES |

Residents: 1. Primary outcome: physicala restraint prevalence 2. Secondary outcomes: (1) Falls, fall-related fractures (2) Quality of life. |

1. Primary outcome (1) After 12 months, physical restraint prevalence was significantly lower in the intervention group 1 (17.4% → 14.6%) (p = 0.042). (2) After 12 months, physical restraint prevalence was significantly lower in the intervention group 2 (19.6% → 15.7%) (p = 0.009). 2. Secondary outcome (1) No significant differences in the secondary outcomes |

- a Significantly different between the intervention and comparison group.

5.1 Research objectives and subjects

The seven papers included in the analysis were all designed to examine the effectiveness of reducing elderly restraint. For the definition of physical restraint, one study (Koczy et al., 2011) was based on the definition of restraint by Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Furthermore, another study (Pellfolk et al., 2010) explicitly excluded bedrails. However, four studies (Abraham et al., 2019; Huizing et al., 2009; Köpke et al., 2012; Testad et al., 2016) considered any restriction on a person's freedom of movement as physical restraint, including the bedrail. Furthermore, one study (Kong et al., 2017) did not define restraint.

In terms of the study population, six studies (Abraham et al., 2019; Huizing et al., 2009; Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Pellfolk et al., 2010; Testad et al., 2016) were conducted among residents, all of whom were elderly, and the majority of whom were female. For the sampling criteria, two studies (Köpke et al., 2012; Pellfolk et al., 2010) used physical restraint for 20% or more of the residents in the facilities; however, one study (Abraham et al., 2019) did not consider it necessary to specify the rate of physical restraint. Additionally, in one study (Koczy et al., 2011), at least five residents used physical restraint. The exclusion criteria were Korsakov's disease and mental illness (Huizing et al., 2009) and the absence of residents on the day of evaluation (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012). Furthermore, three studies examined from the age of care providers, two of which (Huizing et al., 2009; Pellfolk et al., 2010) had an average age of 37–43.5 years, while the sample in Kong et al. (2017) was over 50 years old. These three studies were conducted on female subjects. About the sample criteria, only one (Kong et al., 2017) specified that each nursing home had more than 70 care providers who had experience with physical restraint, had not received any education about restraint in the past 6 months.

5.2 Interventions

Six of the seven studies were based on theory (Abraham et al., 2019; Huizing et al., 2009; Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2017; Testad et al., 2016) to design interventions. All literature interventions were led by nurse specialists or unit leaders, or representatives to give care providers' interventions. Nursing staff includes registered nurses, licensed practical nurses and nurse's aides (Huizing et al., 2009; Kong et al., 2017; Pellfolk et al., 2010), whereas Testad et al. (2016) included all staff working in nursing homes, including non-nursing staff. Interventions include multifactorial interventions (4 papers), education (2 papers), education and consultation (1 paper) (Table 1).

The multifactorial interventions in four studies (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2017) consisted of policy statements on minimum restraints, education (40–90 min/session, 1 to 3 sessions), intensive training (6 h to 1.5 days), consultation (1 hour/session, 2 h/2 weeks), alternatives and provision of support (e.g. providing needs and advice to care providers, residents, relatives and legal guardians), with a duration of 6 weeks to 6 months for the restraint reduction program (Table 1). Education was adopted in one study (Pellfolk et al., 2010): in addition to representatives who participated in a 2-day education seminar, other care providers attended one education session per month, 30 min each time for 6 months, which was effective in increasing the knowledge of care providers or reducing restraints. However, concerning education in a study (Testad et al., 2016), in addition to unit representatives participating in group discussions and 2-day seminars, other care providers attended a 1-h session per month for at least 7 months, which resulted in a significant reduction in restraint rate in the control group compared to the experimental group. In terms of education and consultation in a study (Huizing et al., 2009), the participants attended a 2-h education program (90 min of education and 30 min of consultation) for five sessions for 2 months, and 1–4 h of consultation each time, at least once a week for 8 months, but they were not effective in reducing restraint. Overall, the above RCT literature suggests that educational interventions are a common strategy to reduce physical restraints among older residents in nursing homes.

5.3 Measurement methods

The outcome scores covered both care providers and residents. For care providers, physical restraint knowledge, attitudes (Kong et al., 2017; Pellfolk et al., 2010) and restraint status (Pellfolk et al., 2010) were included. Based on residents, the main results were restraint rate (Abraham et al., 2019; Huizing et al., 2009; Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Testad et al., 2016). While the secondary results included restraint type, restraint intensity, multiple restraints (Huizing et al., 2009; Koczy et al., 2011), falls and related injuries (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Pellfolk et al., 2010), use of psychotropic drugs (Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Pellfolk et al., 2010; Testad et al., 2016), behavioural symptoms (Koczy et al., 2011; Testad et al., 2016) and quality of life (Abraham et al., 2019). Only one of these trials (Pellfolk et al., 2010) evaluated the effectiveness of physical restraint implemented by care providers and physical restraint status among residents.

5.4 Efficacy of physical restraints

First, in terms of care providers, two trials (Kong et al., 2017; Pellfolk et al., 2010) confirmed that a restraint reduction program could increase care providers' knowledge. Contrastingly, the effectiveness of care provider attitudes (Kong et al., 2017) and restraint reduction (Pellfolk et al., 2010) were only confirmed by one trial each. In terms of timing, the effectiveness of the restraint reduction program on care providers' knowledge was confirmed 6 weeks after the intervention (Kong et al., 2017) and 6 months after the intervention (Pellfolk et al., 2010).

Second, in terms of residents, five trials (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Pellfolk et al., 2010; Testad et al., 2016) demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the restraint rate, with one of them (Koczy et al., 2011) confirming the effectiveness of the restraint reduction program on the restraint intensity. However, one study (Huizing et al., 2009) showed no effect in reducing the restraint rate. Three trials (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012; Pellfolk et al., 2010) demonstrated no restraint reduction on falls and related injuries. Four trials (Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Pellfolk et al., 2010; Testad et al., 2016) confirmed no significant increase in restraint's adverse effects reduction programs on psychotropic drug use. Two trials (Koczy et al., 2011; Testad et al., 2016) proved that restraint reduction programs had no significant effect on behavioural symptoms (agitation).

In terms of timing, the reduction in restraint rate was achieved at 3 months (Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011), 6 months (Köpke et al., 2012; Pellfolk et al., 2010) and 12 months (Abraham et al., 2019) after the intervention. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of falls, fall-related injuries (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012; Pellfolk et al., 2010), psychotropic drugs (Köpke et al., 2012; Koczy et al., 2011; Pellfolk et al., 2010; Testad et al., 2016) and behavioural symptoms (agitation) (Koczy et al., 2011; Testad et al., 2016). Nevertheless, Testad et al. (2016) found that at 7 months after the intervention, there was a significant reduction in the restraint rate in the control group (18.4% → 8.8%) compared to the experimental group (19.3% → 18.1%) (p < 0.001; p = 0.025).

5.5 Methodological quality and risk of bias

The quality of the research literature was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, and the results of the quality assessment of seven studies are shown in Table 2. Five trials (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012; Kong et al., 2017; Pellfolk et al., 2010; Testad et al., 2016) described methods for generating or assigning random sequences. Three RCTs (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012; Kong et al., 2017) had appropriate control on the confidentiality principle. One trial (Kong et al., 2017) was blinded to participants and researchers. Three trials (Abraham et al., 2019; Huizing et al., 2009; Köpke et al., 2012) presented blinding of outcome assessors and were rated as low risk of bias.

| Authors (year) | Random sequence generation (selection bias)a | Allocation concealment (selection bias)a | Blinding of participants and researchers (performance bias)a | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)a | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)a | Selective reporting (reporting bias)a | Other biasa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Huizing et al. (2009) | ? | ? | − | + | ? | + | ? |

| 2. Pellfolk et al. (2010) | + | ? | − | − | + | + | ? |

| 3. Koczy et al. (2011) | ? | ? | ? | − | ? | + | ? |

| 4. Köpke et al. (2012) | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? |

| 5. Testad et al. (2016) | + | ? | ? | − | ? | + | ? |

| 6. Kong et al. (2017) | + | + | + | − | ? | + | ? |

| 7. Abraham et al. (2019) | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? |

- Note: +, low risk of bias; ?, unclear risk of bias; −, high risk of bias.

- a Criteria for judging the risk of bias were based on the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing the risk of bias (https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_8/table_8_5_d_criteria_for_judging_risk_of_bias_in_the_risk_of.htm).

Four studies (Huizing et al., 2009; Koczy et al., 2011; Pellfolk et al., 2010; Testad et al., 2016) had dropout rates or loss to follow-up of over 20%, and one of them performed an intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis and was rated as low risk of bias. Seven RCTs could report results as predetermined in the study and were rated as low risk of bias.

Deeks et al. (2011) suggested that any type of variability among studies in systematic reviews can be heterogeneous. This includes clinical heterogeneity (variability in participants, interventions and study outcomes), methodological heterogeneity (variability in study design and risk of bias) and statistical heterogeneity (differences in intervention effects assessed across studies). When there are fewer than 10 studies, meta-analysis should not usually be considered (Higgins et al., 2022; Ryan et al., 2016). The inclusion of studies in the meta-analysis was considered inappropriate due to incomplete data (participants) or the heterogeneity in presentation (interventions and outcomes) in the literature, especially when only seven trials were included.

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 Research objectives and subjects

The purpose of all seven studies was to investigate the effectiveness of reducing elderly restraint. The definition of physical restraint in the literature is that any restriction on individuals' freedom of movement is considered physical restraint, including bedrails (4 articles), which agrees with Möhler et al. (2012). The use of bedrails is common in clinical practice, and many studies (Brugnolli et al., 2020; Lan et al., 2017; Möhler et al., 2012) refer to inconsistencies in the definition of body restraint, with different definitions of the use of bedrails. Lan et al. (2017) still suggest that the definition of physical restraint should be consistent and expressly stated in the article.

Care providers in the study were primarily female, with an average age of 37–43.5 years (2 articles), and residents were mainly female elderly, which accords with several studies (Hofmann & Hahn, 2014; Huang et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2014) that women live longer and are more likely to be admitted to a long-term care facility when disabled. One article specified the characteristics of care providers in each nursing home, and the inclusion (4 articles) and exclusion (3 articles) criteria for resident selection were consistent with Lan et al. (2017) suggestion. Both resident characteristics and the work environment of care providers affect the use of physical restraints.

6.2 Interventions

The results of this study indicated that six of the seven studies designed interventions based on theory. Several trials used decision-making process and empirical guidelines (4 papers), and one trial each applied the theory of planned behaviour (1 paper) and the theory of change (1 paper) as strategies for implementing restraint reduction programs; however, there was insufficient evidence to evaluate or discuss these theories or to evaluate or discuss in-depth whether the results confirmed the theory (Lan et al., 2017; Möhler et al., 2012). However, “reducing restraint in care” is the desired goal for all long-term care providers (Kong et al., 2017; Kor et al., 2018) and is the goal for the highest quality of care (Möhler et al., 2012); thus, ongoing quality assessment and management is essential to ensure the quality of care.

Three out of the seven trials identified nursing staff as including registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nurse's aides; their restraint reduction programs were targeted at the nursing staff, and interventions were provided by nurse specialists or unit leaders, which were consistent with Hubbs (2013) and Möhler et al.'s findings (2012). Three other publications supported education or consultation of care providers by specialist nurses or unit leaders (American Nurses Association, 2012; Gulpers et al., 2013; Möhler et al., 2012) and indicated that only trained care providers should implement restraints (Dikiciyan, 2012).

The interventions in restraint reduction programs include (1) multifactorial interventions (4 articles) such as policy statements on least restraint policies, education, intensive training (workshop training and consultation), consultation and provision of support; (2) education (2 articles); and (3) education and consultation (1 article). Four multifactorial interventions and one educational intervention improved care providers' knowledge and attitudes, or reduced restraints, which agrees with Lan et al. (2017).

In summary, there is evidence to support the use of multifactorial interventions over single interventions, such as policy changes (reducing the use of restraint policies), education and consultation (by specialist nurses or unit leaders for care providers), development and provision of alternative interventions (e.g. sensor pads, balance training, exercise, special pillows and lowering bed height), and the inclusion of residents and family members (Gulpers et al., 2013).

6.3 Measurement methods

In this paper, the outcome evaluations involved both care providers (restraint reduction knowledge, attitudes and behaviours) and residents (restraint rate, restraint type, restraint intensity, multiple restraints, falls and related injuries, psychotropic drug use, behavioural symptoms and quality of life). Only one study (Pellfolk et al., 2010) evaluated the effectiveness of both care providers and residents, and the results of this study are consistent with those of Möhler et al. (2012) and Lan et al. (2017).

Reduced physical restraint can be considered a quality indicator of long-term care (Fashaw et al., 2020; Mashouri et al., 2020) and is, therefore, associated with physical injuries in the older people, such as immobilization leading to functional decline, pressure sores, falls and cognitive decline (Hofmann & Hahn, 2014), depression (Fariña-López et al., 2013), and quality of life (Hubbs, 2013; Möhler et al., 2012). None of the included trials investigated the impact of the restraint reduction program on physical functioning, pressure sores and depression of residents in nursing homes.

Care providers' knowledge of restraint implementation may influence their attitudes and behaviours toward restraint implementation (Azab & Negm, 2013). Nurses are often the first line of decision-makers about restraint, and care providers are the restraint implementers. Therefore, to implement restraint reduction care, it is vital to understand care providers' knowledge and attitudes about restraint reduction (Azab & Negm, 2013; Kor et al., 2018).

6.4 Efficacy of physical restraints

This study's findings highlight a restraint reduction program's effectiveness in improving care providers (restraint reduction knowledge, attitudes and behaviours) and residents (restraint rate, restraint intensity, falls and related injuries, psychotropic drug use and behavioural symptoms) in nursing homes. Such results agree with the findings of Brugnolli et al. (2020) and Lan et al. (2017); however, their systematic review and statistical analysis were effective only in residents (restraint rate). Moreover, the present study results differ from those of Möhler et al. (2012), whose systematic review only demonstrated ineffectiveness in residents (restraint rate). The possible explanation is that the purpose of the present study and the inclusion criteria varied (intervention type and outcome variables), thus causing different results.

Among the indicators included in the trials for residents, one educational intervention (Testad et al., 2016) instead showed a significant reduction in restraint rate in the control group compared to the experimental group, possibly because the Norwegian government at that time had a comprehensive staff education program and legislative policies in place to support nurses' attitudes and behaviours to reduce restraint. Alternatively, the intervention of education and consultation (Huizing et al., 2009) was not effective, which may be related to the need to explain the definition of physical restraint, the characteristics of dropouts (older and impaired) during the study period, and whether the control group was provided with general routine care or optimized routine care.

6.5 Methodological quality and risk of bias

Five of the seven included studies described random assignment procedures, which are a lottery system using identification codes (Pellfolk et al., 2010), computer-generated randomization (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012), listing nursing homes in random order (Testad et al., 2016), sealed opaque assignment envelopes (Kong et al., 2017), to determine the randomization mode and to achieve a balance between the experimental group and the control group, rated as low risk of bias. However, in one paper (Abraham et al., 2019), due to poor communication, participants who should have been randomized to intervention group 1 were incorrectly assigned to the control group; however, the authors did not consider this to be a risk of bias as they had done sensitivity analyses on the primary outcomes, which showed comparable results. The other two articles (Huizing et al., 2009; Koczy et al., 2011) only mentioned conducting randomized trials, but they did not give details on how the randomization process was conducted, nor did they give details on the participant selection method, possibly suggesting that the selection of subjects was based on non-probability sampling for convenience (Hubbs, 2013).

Three studies described concealed assignment grouping, either by envelope method (Kong et al., 2017) or by non-participants (Abraham et al., 2019; Köpke et al., 2012). One trial presented blinding of participants and researchers. Furthermore, three trials presented blinding of outcome assessors, which would avoid leading to the Hawthorne effect or assessor bias that reduces intrinsic validity (Hubbs, 2013).

Four studies had dropout rates or loss to follow-up of more than 20%, and one of them performed an ITT analysis to overcome attrition bias. Seven RCTs in the literature could present the results in the manner predetermined in the program. Möhler et al. (2012) suggested that reporting bias was unlikely to affect the results because of the extensive literature search of the registered trials in electronic databases (PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, etc.).

This study used the RCT system to evaluate the impact of restraint reduction programs on older adults' physical restraints in nursing homes. This review's strength is that it analyses only RCTs on the impact of physical restraints on residents implemented by care providers and the impact on residents' physical restraint status. The results demonstrate that a restraint reduction program led by nurse specialists or unit leaders and targeting care providers provides multifactorial interventions and improves restraint reduction more effectively than an education or consultation intervention alone. The program includes policies that promote institutional restraint reduction, educational sessions (40–90 min/session, 1–3 sessions), consultation (1 h/session, 2 sessions), development and provision of alternative interventions, and support. The duration of effective restraint reduction programs is 6 weeks to 6 months: at least 6 weeks significantly improves care providers' knowledge. The duration of at least 3 months significantly improves the restraint rate of residents. Outcome measures should cover both care providers (restraint reduction knowledge, attitudes and behaviours) and residents (restraint rate, restraint type, restraint intensity, multiple restraints, falls and related injuries, psychotropic drugs, behavioural symptoms, quality of life, physical functioning, pressure sores and depression).

6.6 Limitations

This review has several limitations: (1) Our criteria for inclusion of articles were limited to Chinese and English literature only, and we did not include unpublished literature or manuscripts, which may have omitted parts of the literature, resulting in sampling bias and publication bias and affecting the analysis results; (2) the literature was not included in the meta-analysis due to incomplete data or differences in presentation; and, (3) being limited to the term “restraint reduction program” may have led to the omission of some interventions that were not identified as restraint reduction programs due to inconsistent definitions of restraint. Inconsistent definitions of restraint may lead to different restraint reduction outcomes, such as whether the use of bed rails is considered physical restraint or not (Huizing et al., 2009), but this may be a subject for future research.

7 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, five of the restraint reduction programs effectively reduced the rate of physical restraint use; two increased knowledge of restraint reduction for care providers; and one each promoted positive attitudes and behaviours. This review further demonstrates that restraint reduction programs, particularly those led by specialist nurses or unit leaders, can use multifactorial interventions (policies to promote institutional restraint reduction, education, consultation and development of alternatives) for a minimum of 6 weeks or more to improve care providers' knowledge, attitudes and behaviours about physical restraint and reduce the implementation of restraint. Therefore, this may be a valuable strategy for reducing older adults' physical restraints in nursing home in the future.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Su-Hua Liang and Tzu-Ting Huang: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization and manuscript preparation and revisions. Su-Hua Liang: Data curation, Project administration. Tzu-Ting Huang: Supervision.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interests to be declared.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Given the nature of the study, no ethical issue were at need to be addressed.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.