Towards negotiation: A RAMESES narrative review of social enterprise to support sustainability in Sport for Social Change (S4SC)

Abstract

This article engages in a systematic narrative review, executed according to RAMESES (Realist and Meta-Narrative Evidence Synthesis) standards, to unpack the literature on social enterprise. The case of Sport for Social Change and Development (S4SC) is presented as a global field of organizations facing early engagement with the concept of social enterprise as an innovative solution to increasing pressure in the NGO landscape. Yet, social enterprise is a complex term, which requires a solid theoretical approach before gaining currency as an operational term in the S4SC field. As researchers, we need to first and foremost consider how our research in this area supports organizations. Due to this, the way we theorize a concept before operationalizing the concept needs to appreciate the lived reality of these organizations and the efficiencies they aim to gain to benefit their social mission. The RAMESES narrative review is engaged to consider the different angles of thought regarding social enterprise. Findings articulate three prominent methods to conceptualize social enterprise and query how these methods can be used to support the development and growth of the social enterprise model in the S4SC field. Concluding remarks suggest that research on social enterprise in S4SC needs to better understand the purpose of this concept in the field to mitigate any risk of a priori assumptions being imposed on these organizations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Certain environmental conditions create a sense of insecurity for traditional community-based non-profit organizations to address their social purposes. This includes an increase in funding competition with other non-profits (Young, Salamon, & Grinsfelder, 2002; Mikołajczak, 2019); policy changes that potentially contribute to new social challenges or an increased population of organization beneficiaries (Maier, Meyer, & Steinbereithner, 2016); and a “failure” of the market and public sector to address development challenges (Lee, Battilana, & Wang, 2014). These challenges hinder organizations' capacity to foster lasting social change, scale their impact, and maintain and grow a dedicated workforce (Rottkamp & Bahazhevska, 2016). Ultimately, this is a challenge to organization efficiency. As a result, organizations have sourced more innovative approaches rather than relying solely on the traditional methods of program delivery and resourcing (Roy, Donaldson, Baker, & Kerr, 2014). Coupled with this, there is ongoing pressure on the organizations to be more accountable and business-like in their management practices (Eikenberry & Kluver, 2004; Marciszewska, 2014).

Social enterprise is a means to face this challenging environment. However, the overall development of this form of community-based organization is tested by broad conceptualizations and diversity of operation. For example, scholars have proposed a myriad of definitions including “nongovernmental, market-based approaches to address social issues” (Kerlin, 2013, p. 84); NGOs that have their own earned-income strategies or “for-profit” approach (Katz & Page, 2010; Singh & Singh, 2014); organizations that meet the triple-bottom line by “achieving economic, social, and environmental value by trading for a social purpose” (Haugh, 2012, p. 9); organizations that put people first and, through their economic activities, seek to deliver employment opportunities and other social, environmental, or community benefits; and “organizations that use market solutions to address pervasive social problems” (Hoffmann, 2016, p. 40). How does a field of community-based non-profits interested in social enterprise development begin to make sense of this conceptual incongruity? Furthermore, how does this inform the research process? We employ a RAMESES (Realist and Meta-Narrative Evidence Synthesis) narrative review to address this question. This review has a simple aim: to draw out the main conceptual considerations addressed by researchers to query what may inform social enterprise conceptualization by the unique, global case of community-based non-profits, Sport for Development and Social Change (S4SC).

The structure of this review is as follows. First, we make an introduction to the S4SC field and a unique, global study on social enterprise, S4SC, and organization sustainability. This is achieved not only to introduce a gap in the S4SC and social enterprise literature, but to highlight the methodological underpinnings of this literature review, an evaluation approach known as Fourth Generation Evaluation (4GE). We turn to the literature to ensure that as a research team we are both teacher and learner. We must enter our interviews armed with theoretical knowledge for the purpose of assimilating end-user experiences into our own background (Guba & Lincoln, 1989). Moving forward, we provide a description of how we addressed each step of the narrative review. Based on the reviewed literature, three social enterprise conceptual entry points are described. In our discussion, we present a paradigm that frames how the key conceptual approaches to social enterprise may inform an end-user's conceptualization of the term. In conclusion, we argue this paradigm must inform our engagement with the study's end-users to ensure that we do not impose social enterprise interpretations onto the organization during the research process.

1.1 Social enterprise and S4SC

This current study is situated in a larger, global study that aims at contributing to the development of social enterprise theory for S4SC. Sport is more than just a platform for entertainment and competition; it is a tool for social change when used intentionally and with purpose (UNICEF, 2003). Therefore, S4SC is the umbrella term referring to organizations that use sport to yield “positive influence on [the] public health” of often marginalized and vulnerable communities (Lyras & Peachey, 2011, p. 311). Over 900 community-based organizations across low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries engage this approach to address the social determinants of health, including increasing social inclusion, building community capacity, and fostering social change (Nathan et al., 2013; Whitley et al., 2019). On an important note, we understand that for many scholars, this field is bigger than just the community-based non-profit. For example, some scholars argue community sport programs should be considered in this field. This brings existing sport programs and governing bodies into the boundaries of the S4SC field. However, we agree with those who consider S4SC as operations outside of existing sports systems (Peachey, Schulenkorf, & Spaaij, 2019; Thorpe & Chawansky, 2017). Svensson, Hancock & Hums (2017) provide a prominent argument in our favor by suggesting the “social change-focused mission” of the community-based non-profit differentiates them from the traditional sport organization and from sport governing bodies (p. 2). In addition, we find community-based non-profits operate most of the S4SC programs, though with the support and cooperation of other actors such as international NGOs, community-based non-profits, governments, and corporations (Giulianotti, 2011; Giulianotti & Armstrong, 2013).

Until recently, there has been an absence of research dedicated to understanding “the provision and actual management of these S4SC programs” in order to discuss the “associated practical and policy implications” (Schulenkorf, Sherry, & Rowe, 2016, p. 1). To address this gap, social enterprise has become an emerging concept in the S4SC scholarship. However, it is rarely queried on its own and typically folded into research on social innovation and/or social entrepreneurship (e.g., Hayhurst, 2014; Svensson & Mahoney, 2020). This muddies the conceptual clarity of what social enterprise actually means. It is important to distinguish the differences between these terms and social enterprise to ensure we do not provide misguided representations (Peredo and McLean, 2006).

For example, Hayhurst (2014) introduces the concept of social enterprise in her study on the impact of the Nike “Girl Effect” program. She argues social entrepreneurship is a viable strategy for this organization to face the environmental challenges we cited earlier. This occurred in two ways. First, the program empowers female youth to become social entrepreneurs to face gender stigmatization in their communities. Svensson and Cohen (2020) note a similar form of innovation in the Play International program and the Playlab experiment. This is a program that is designed with the intent to promote social entrepreneurship amongst program youth. Second, she introduces the term social enterprise as a mechanism to cut ties from the “purse strings of donors” (p. 310). By employing both these forms of entrepreneurship, the organization should engage in smart development economics to empower the organization and the youth. It is probable that Hayhurst considered that social enterprises are vessels for social entrepreneurial activity (El Ebrashi, 2013). However, we did not find explicit clarification to distinguish the two.

Other scholars query the antecedents of social innovation in the field (Svensson et al., 2020a,b; Whitley et al., 2019). One such study explores how to resource social innovation. Whitley et al. (2019) argue that one antecedent to social innovation is a comprehensive realignment of funders intention to the innovation goals of the organization. Joachim, Schulenkorf, Schlenker, and Frawley (2020) suggest a reorientation of S4SC management so that innovation will stem from a human-centered design. Yet, it is Svensson's complex work on organizational capacity and social innovation that provides much of what we know about social enterprise within the field to date (Svensson & Cohen, 2020; Svensson, Mahoney, & Hambrick, 2020). One key study (Svensson, 2017) explores social innovation through hybrid logic. Organizations adapt their traditional models to respond to environmental stresses. In order to do this, they must balance competing institutional values, beliefs, rules, and systems (“the logics”), which may not have been present in early program delivery. How they balance them informs the overall hybrid model of program delivery. Svensson (2017) offers insight into how this occurs in the S4SC organization. For some, they may adapt their funding strategy and balance the new funder's values with their own. Others may engage in a differentiated model. In this model, for example, a revenue-generating activity is structurally different than the social delivery. What Svensson (2017) offers in this article is an introduction to social enterprise organization structure. These structures are those we may find in the S4SC space. He clarifies that these types of innovation taken by the community-based non-profit is dependent on the context of the organization.

Despite these efforts, there remains a “discrepancy between theory and practice” and how to progress innovations in the S4SC field (Svensson & Cohen, 2020, p. 139). Svensson and Cohen (2020) claim that despite this, “it is just as crucial to relay these findings to SDP [S4SC] stakeholders” (p. 142). However, in our experience, this is not enough when it comes to working through complex, umbrella-like terms such as social enterprise and social innovation. Although these findings stem from methodological practice which is typically participatory in nature (e.g., Giulianotti, Coalter, Collison, & Darnell, 2019; Joachim et al., 2020), participation requires a strong paradigmatic foundation and protocol that structures how we give voice and give accountability to those living the experience (Oetzel et al., 2018). For our purposes, it is best to negotiate the conceptual underpinnings of social enterprise with the end-user before operationalizing the term in our own study. Why we assume this is explored below.

1.2 Background and purpose

Not surprisingly, finance plays an integral role in the capacity of the organization, making it this study's original entry point into social enterprise theory (Svensson & Cohen, 2020; Svensson & Hambrick, 2019). There are financial challenges within the field that cannot be missed. Kidd (2008) went so far to claim that they are “woefully underfunded” alongside being poorly planned and unregulated. Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, the financial realities become more evident and frightening for the survival of the field. Approximately 56.2% of organizations believe that it will take up to 3 years to recover to a pre-pandemic level of funding and program delivery (Oaks Consultancy, 2020).

This research team, working in partnership with the largest network of S4SC organizations, Streetfootballworld (SFW),1 has developed a global, in-depth exploration of social enterprise in the field of S4SC for the purpose of supporting the ongoing development of a social enterprise capacity-building program. A pilot survey provided our initial step into this research by mapping the types of sustainable funding mechanisms used in the field of S4SC. In response, 27 S4SC organizations indicated the development of social enterprise activity within the past 5 years to face the challenges associated with the “non-profit starvation cycle” (Elkington, Bunde-Birouste, & Apoifis, 2019). In-depth follow-up was conducted during a series of preliminary capacity-building events. In addition to providing key insights, this initial exploratory process made us question the research team's interpretation of social enterprise. At this junction of the process, our interpretation of social enterprise aligned with an earned-income description (Arpinte, 2010; Kerlin, 2010). Defourny and Nyssens (2017) explain this as the entrepreneurial non-profit (ENP), an organization with a trading arm to earn income that will directly support their social programs. They pursue commercial activity alongside traditional non-profit operations and governance to “compliment public grants and donations with new sources of funding” (Defourny & Nyssens, 2017, p. 2481). Yet, not all organizations querying a transition to social enterprise aligned their interest to this definition.

This study, in response, sought a methodology that puts the voices of the study end-users first. Community-based non-profits often fall subject to the whims of external stakeholders, and many times, this can include the researcher (Anheier, Simmons, & Winder, 2007). This can lead, though not all the time, to an understanding and appreciation of the dimensions of the research that are possibly limited and biased (Johansson, Ericsson, Boström, Björklund, & Fristedt, 2018; Potvin & McQueen, 2008). We observed this bias in our own research. Therefore, we engage Fourth-Generation Realist Evaluation (4GE). This evaluation protocol promotes the negotiation between researcher and end-user, whereby both are participants in developing the research trajectory. The end-users enter into negotiation as lived experts on the topic. The researcher, in contrast, enters with a firm theoretical foundation.

For the purpose of this study, we must therefore return to the literature to firm up an approach to how we can conceptualize social enterprise for the purpose of this negotiation (Guba & Lincoln, 1989). We engage in a systematic narrative review, executed according to RAMESES standards, to address the question: How can we communicate social enterprise in negotiation with SFW network members who look to transition to a social enterprise model? We first present why RAMESES is an appropriate method of synthesis. Then we turn to a description of our findings before presenting the conclusion.

2 METHOD

2.1 The narrative review

We draw on the guidelines of the RAMESES narrative review. Review types such as the systematic or meta-analysis predominantly aim at identifying gaps in research and subsequently form hypotheses, which may fill these gaps (Gunnell, Poitras, & Tod, 2020). The narrative review does not take this approach. We aim at viewing social enterprise “through multiple sets of eyes,” a nod to the realist underpinning of this review type and our understanding that context informs how researchers ask their questions (Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, & Pawson, 2013, p. 2). Based on this, we create a narrative arc to credit the different perceptions. For the quality assurance purposes of this review, the established 20 RAMESES standards were followed to ensure validity and reliability of the findings (Wong et al., 2013). The following is laid out according to these steps. Table 1 provides a description of how we engaged each task. For conceptual purposes, we have aggregated the steps into high-level dimensions to remain considerate of the length of the paper. Those that merit further description are illustrated by the subheadings. The following search and appraisal were conducted by three members of the research team.

| Step | Step name | Description of our engagement with guideline |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Name a title | Title of the document includes identification of document as RAMESES narrative review: “A Negotiation, not an Imposition: A RAMESES Narrative Review of Social Enterprise for Sport for Social Change (S4SC)” |

| 2 | Develop an abstract | The abstract clearly describes why we entered this study to inform the development of social enterprise theory as a negotiation between researchers and practitioners. Present our question: “how can we communicate social enterprise in negotiation with Streetfootballworld (SFW) network members who look to transition to a social enterprise model?” |

| 3 | Identify rationale of review | Clearly explains the purpose of the review. As described, we want to face the current challenge across social enterprise literature within the S4SC field and clarify what social enterprise means in this field. |

| 4 | Identify objectives and focus of review | Introduction highlights that we require a communication approach that does not impose our assumptions of the term but enables us to come to the table with all options available, but in a synthesized manner |

| 5 | Clarify any changes made to the review process | No changes were made to the review process |

| 6 | Explain why RAMESESS was selected | Introduction to the methods clearly highlights we require the narrative RAMESES guidelines to inform the field's consideration of social enterprise. By looking through the eyes of other authors, we will build understanding that broadly considers social enterprise across research approaches. |

| 7 | Describe how process adheres to RAMESES guidelines | Provides this table to identify our engagement with the RAMESES process. |

| 8 | Scope literature | Explains how we engaged with the SFW network members, literature, and conferences on social enterprise to firm up our assumption that social enterprise is a broadly defined and operationalized concept across fields, not only S4SC |

| 9 | Conduct literature search | Clearly identifies ProQuest and Scopus as the most appropriate search databases; confirms the associations of terms submitted to the literature so that the literature returned is most reflective of the study objective |

| 10 | Select and appraise documents | Clear articulation of why we excluded terms in our literature search process and why this was reflective of our study objective |

| 11 | Extract data | Clearly defines in Table 3 the criterion we searched in review of all abstracts searched following the return of the literature. |

| 12 | Analyze and synthesize data | Conducted coding of the returned abstracts; analysis coded broadly for research approach particularly looking at the types of questions being asked within the literature and the concepts they use within these questions. This will help us understand the key concepts in social enterprise literature as it pertains to non-profits and their purpose in social enterprise development |

| 13 | Provide flow diagram | A flow diagram documents this process from step 8 to step 12 |

| 14 | Explain why documents chosen for findings | Documents chosen specifically illustrated an association between non-profit and social enterprise and offered new ways to consider this association |

| 15 | Describe key findings | We present a list of the three key findings, which reflect the three parent codes we uncovered during the analysis |

| 16 | Provide summary of findings | Present findings by explaining and describing the key narratives that arose through our coding; the narrative we aim to tell is how researchers interpret social enterprise in non-profits and how that influences how understanding of how to negotiate social enterprise in S4SC |

| 17 | Discuss strengths, limitations, and future research | This is found in our conclusion where we highlight the strengths of negotiation to work with the S4SC field to interpret social enterprise holistically. Here, we highlight key concepts that should be further explored in future research. |

| 18 | Compare with existing literature | We explain our concluding thoughts against the literature on S4SC and social enterprise presented in the introduction of this review |

| 19 | Provide recommendations | The recommendations we provide are in line with the limitations we identify. |

| 20 | Explain funding if applicable | There was no funding support for this article |

2.2 The literature search process

We first conducted an informal exploration of the current literature on social enterprise (Wong et al., 2013). We found this is a particularly appropriate step to commence a literature search exploring social enterprise as the concept “remains hard to grasp” because at the core of the term is a “complexity of overlapping key concepts [which] create major challenges” (Maier et al., 2016, p. 64). We initiated the conversation with those across the SFW network, including members of the steering committee and respondents to the pilot survey. We also read publications and attended two conferences on social enterprise to broaden our interpretation of the concept to be applied to this research. Following this initial foray into the literature, we found it is in our best interest to source information on social enterprise, which associates across multiple research approaches and terms. However, we must only consider the literature, which regards the community-based non-profit as the key actor engaging in enterprise activity, rather than a corporation (Ridley-Duff and Bull, 2015; Trivedi & Stokols, 2011).

Based on this initial foray, we selected Scopus and ProQuest as appropriate databases to conduct the next, in-depth search. These databases were selected based on their multidisciplinary approach to index and provide access to bodies of knowledge. For example, it was beneficial to this review to aggregate literature across the ProQuest index of databases, including those related to humanities, education, business, and public health. This ensures we give credit to the underpinning health and development objectives as well as the models of program delivery across the S4SC field. We conducted an individual search for each association of terms selected, which encompass the social enterprise literature (i.e., “social enterprise*” AND “NGO*” as one search, and “Social enterprise* AND “non-profit*” as another, and so on and so forth). The list of associated terms to social enterprise included: “NGO*”, “nongovernmental organization*”, “non-profit*,” “NPO*,” and “non-profit organization*,” “third sector,” “civil society,” and “social economy.”

Inclusion of the broad terms social economy, third sector, and civil society was considered necessary to account for, either rightly or wrongly, their occasional, synonymous use across the literature (Viterna, Clough and Clarke, 2015). According to scholars, these terms encompass a myriad of individual activities and institutions including non-profits, non-governmental organizations, independents, charities, faith-based organizations, and voluntary organizations (e.g., Corry, 2010; Dacheux & Goujon, 2011; Salamon, Hems, & Chinnock, 2000). Specifically, within this literature, we are interested in the community-based organizations, which engage in problem-solving, advocating, shaping society norms and articulating society purpose, and democratic change. Therefore, further inclusion of the terms non-profit, non-governmental organizations, and associated entries were submitted (Knutsen, 2016). Many times, the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and non-profit organization are used synonymously, but this is not without flaw and conceptual incongruity (Salamon & Anheier, 1997; Salamon & Sokolowski, 2016). For some, the NGO is subsumed within the non-profit literature or the private arm of governments' international interest (Sama, 2009). Yet, for others, such as conceptualizations in the United States, the NGO broadly accepts the place of the non-profit and arguably shares the same purpose. We cannot, for the purpose of this review, delineate by law or organizational structure, as these are too context-dependent for the scope of organizations we aim to support (Til, 2009).

We included all articles between 2000 and 2020. These dates were chosen in consideration of the most contemporary conceptualizations of the term. Even though social enterprise is not a novel concept, it has been continually refined and reworked with considerable efforts since the early 2000s (Sepulveda, 2015). The search was limited to English, peer-reviewed articles and editorials where the full-article was available. Title, abstract, and keywords were initially searched, returning 1,238 articles (See Table 2). This was conducted within the study objective to consider the association between social enterprise and existing community-based organizations. Thereby, if the association was not made within the abstract, title, or keyword, then it was not the key consideration of the article. Articles were then collated across databases and checked for duplicates, resulting in the removal of 411 articles.

| Search association | Database: ProQuest | Database: Scopus |

|---|---|---|

| Return # | Return # | |

| “Social Enterprise” AND “NGO*” | n = 29 | n = 110 |

| “Social Enterprise” AND “non-governmental organization*” | n = 8 | n = 38 |

| “Social Enterprise” AND “NPO*” | n = 9 | n = 21 |

| “Social Enterprise” AND “non-profit*” | n = 110 | n = 182 |

| “Social Enterprise” AND “non-profit organization*” | n = 78 | n = 66 |

| “Social Enterprise” AND “third sector” | n = 55 | n = 166 |

| “Social Enterprise” AND “civil society” | n = 41 | n = 110 |

| “Social Enterprise” AND “social economy” | n = 62 | n = 153 |

2.3 Selection and appraisal of documents

The appraisal phase of the narrative review is not a technical process, but one that brings to light those articles that best contribute to the validity of the literature search. In order to achieve this, we had to map the remaining literature against the study objective in accordance with RAMESES guidelines (Wong et al., 2013). To start this evaluation process, the criteria in Table 3 were set and agreed to by the research team to ensure the results are feasible and reflect the study's purpose (Wong et al., 2013). For example, we considered that those articles that strictly consider social enterprise within medical literature outside the current scope of the SFW network and, therefore, outside of the scope of this review. To start this process, the lead author screened the database hits against the criteria, using title information/abstracts to conduct the review. Where there were any questions, the article was set aside to be dually reviewed and negotiated by the research team. A further removal of 671 articles ensued.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

Given this, articles will be included if they focus primarily on one or a combination of the following:

|

|

2.4 Data extraction, analysis, and synthesis

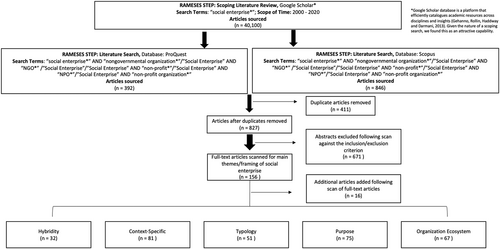

A total of 156 full-text articles were assessed to classify the key concepts reflective of the study objective (see Figure 1). This method led to the identification of an additional 16 relevant references. We conducted thematic coding of these remaining articles. Following an inductive process, we applied descriptive codes to each article (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We placed similar codes (child codes) together, so they formed metacodes (Bazeley, 2013; Saldana, 2016) (see Figure 1). These metacodes were a means to paint a larger picture of the overarching considerations researchers have brought into the discussion of social enterprise as it relates to existing non-profits. This process was iterative as we continued to digest conflicting and complimentary approaches to social enterprise. The child codes will be discussed within our summary of findings. We find these underpin these overarching considerations. However, in reality, there is an overlap of codes across the sourced articles suggesting social enterprise conceptualizations may draw on the same foundations but with different objectives of the explanation. This is illustrated in the flow diagram. In addition, these codes were not based on any particular keywords or phrases within the studies. They represented what the authors believe are the main ways the current research frames the balance between social purpose and financial mission. The primary author was the lead researcher conducting the analysis. Quality assurance was provided by discussion with feedback from the larger research team and colleagues at the researchers' institutional base.

3 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Our review of the literature showed that there are numerous approaches of which a seminal aspect considers the association between social enterprise and non-profits. The literature search revealed five prominent themes, each overlapping and underpinned by notable considerations, which we will review in this summary. What we present here are the three entry points we consider to be the overarching themes within the literature that address our purpose: to draw out the main conceptual considerations addressed by researchers to query how social enterprise transpires in community-based non-profits. We present a description of each of these entry points. Following each description, we present an initial conclusion where we question how this may inform our negotiation with the S4SC organizations. These initial conclusions will contribute towards a synthesis of findings and development of a negotiation approach presented in the final conclusion.

3.1 Social enterprise: Context and purpose

Many scholars find that social enterprise is best understood as a place-based approach (Ferguson, 2018; Mazzei, 2018). In this sense, the concepts associated with social enterprise are based on consideration of context first. For some scholars, this association is made through the relationship of enterprise activity to the social, institutional, and environmental factors within a specific context (Kerlin, 2013). Social enterprise has gained increasing currency to fill key gaps caused by the retrenchment of state welfare and to respond to the inclusion or absence of international interest (Arantes, 2020). What this means is social enterprise is a response to certain socioeconomic factors which influence a context's overall civil sector (Kerlin, 2012; Zimmer & Obuch, 2017). In South Korea for example, the non-profit sector is moving away from state-sponsored approaches providing greater room for bottom-up driven enterprises (Jang, 2017).

Many social enterprise definitions are attributed to a single context, taking into account these contextual factors (Gonzales, Forrest, & Balos, 2013). According to Kerlin (2012) “world regions have come to identify different definitions and concepts with the social enterprise movement in their areas” (p. 91). Pestoff and Hulgård (2016) progress this consideration by claiming that definitions are the results of a particular political agenda. Across our findings, three examples are prominently used as examples, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and EMES, a social enterprise research network that investigates the development of social enterprise across the European Union (Arpinte, 2010; Rostron, 2015). The United Kingdom Department of Trade and Industry defines social enterprise “as a business with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in that business or in the community rather than being driven by the need to maximize profit for shareholders and owners” (as cited in Rostron, 2015, p. 88). The contextual drivers of this definition stem from a retrenchment of welfare funds, and as such, social enterprises are those that benefit the welfare objectives of the country, by creating “new goods and services” where mainstream businesses and potentially, the government, will not go (Spear, 2009).

A more explicit interpretation is found within the United States, whereby the social enterprise definition stems from the role of the social entrepreneur (Pestoff & Hulgård, 2016). The entrepreneur is one that takes risks, innovates, adapts, and pursues any opportunity that will benefit the social purpose (Jones & Keaugh, 2006). Social enterprise is therefore, in this context, a non-profit organization that builds upon these characteristics of the social entrepreneur and moves “away from reliance on more traditional forms of income” by developing their own businesses to approach revenue generation (Arpinte, 2010, p. 154).

The legality of social enterprise is an additional concept to consider as an underpinning descriptor of context-based approaches. Is there a welcoming environment for social enterprise activity (Orhei, Vinke, & Nandram, 2014; Praszkier, Petrushak, Kacprzyk-Murawska, & Zabłocka, 2017)? For instance, recent policy reform has created a welcoming gateway for social entrepreneurship activity to generate new and innovative routes to employability in Italy. This includes the enactment of new legal organizational forms, means of governance, and encouragement of cross-sector interaction and partnership (Pulino, Maiolini, & Venturi, 2019). Yet, this type of environment is not fluid across countries (Doherty & Kittipanya-Ngam, 2020). For example, Hojnik (2020) concludes in her review of social entrepreneurship in Slovenia that there is not a welcoming legal environment to support this activity. What she means by this is that there is an ecosystem surrounding social enterprises, which we must consider when questioning the viability of social enterprise in a specific context. This includes potential for impact measurement and communication, certification, external stakeholder support from businesses, investment market, and the current legal system in which the enterprise will operate. Hojnik concludes that even though there is not a breadth of legal social enterprises, there are many organizations in Slovenia currently operating according to social enterprise principles. What we take away from this is the heightened need for context-based advocacy to create a more welcoming environment for this enterprising activity. In addition, even though there are not always stringent laws to guide social enterprise development, organizations may be able to operate according to social enterprise principles reflective in the social enterprise definitions put forth. Therefore, we may be able to assume that it is up to the organization to articulate the principles, which may be the most welcoming and applicable to their own context (Babić & Baturina, 2020; Monzon-Campos & Herrero-Montagud, 2016).

But why do this in the first place? The literature considers context not only within definition and regulatory environment, but within the social purpose of the enterprise. Roy et al. (2014) suggest that social enterprises exist for the main purpose of alleviating the “preventable and unfair differences between social groups, populations and individuals” (p. 183). This is achieved, for example, by empowering communities with accessible healthcare (Henderson, Reilly, Moyes, & Whittam, 2018); the unregulated sale of basic medicines in impoverished low-income countries (Smith-Nonini, 2016); building capacity of female entrepreneurs (Hossein, 2017); and facilitating community adaptation to the decline of the welfare state by providing opportunities such as housing and employment (Cornelius & Wallace, 2013; Murtagh & McFerran, 2015).

The approach employed by EMES offers potential solution to this challenge to embedding social purpose and context within the definition of social enterprise. We find it does so without strict parameters. These dimensions are guidelines for social enterprises to define as well as refine their approach (see Table 4; Defourny & Nyssens, 2017).

| Economic and entrepreneurial dimensions | Social dimensions | Participatory governance |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous activity producing goods and/or selling services | Explicit aim to benefit the community | High degree of autonomy |

| Significant level of economic risk | Initiative launched by a group of citizens or social society organizations | Decision-making power not based on capital ownership |

| Minimum amount of paid work | Limited profit distribution | Participatory nature, which involves various parties affected by the activity |

3.2 Context, social enterprise, and S4SC

We find there is a clear purpose for social enterprise development. This can be directly attributed to the organization context. Much of the literature focuses heavily on broad institutional factors, such as those articulated by Kerlin (2012). Yet, is in our opinion that the organizations we work with are already filling a key gap in their nation's social economy but are searching for ways to do this more efficiently. Therefore, we draw from this finding very practical insight into the factors that may inform how the existing non-profit organization transitions to a social enterprise model. Without fail, there must be an environment that supports their activity. Clearly, the literature suggests it is easier to progress to this model when policy supports the transition. However, we do find that even without clearly defined legal structures, organizations can continue to draw on the principles of social enterprise. We must also take into account the niche factors within specific contexts, which are attributed to the larger socioeconomic factors. These are defined by the organization's primary purpose such as to provide education, to provide employment, and to foster space for women entrepreneurship. Finally, we also find in this first entry point consideration of social enterprise definitions. Scholars argue that definitions in the social sphere tend to be in flux, yet they remain widely used to describe certain activity within the social enterprise space (Bazeley, 2013). Therefore, it is appropriate for this review to consider definitions as guidelines; potential avenues for social enterprise operationalization that may be fluid across context. Context-based explorations into social enterprise, though offering strategically narrow insight into particular cases, are a lens into the varying social enterprise typologies.

3.3 Purpose: A matter of model and typology

For the second entry point, we find researchers consider organization purpose through the lens of institutional logic (Besharov & Smith, 2014; Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, 2015). These logics are the overarching norms, values, missions, and rules that guide enterprise development (Battilana and Dorado, 2010; Thornton et al., 2015). In the transition to social enterprise from traditional non-profit, these logics are subject to change, whereby the innovation the organization seeks may not be directly aligned to the organization's existing values and beliefs. This potentially leads to ethical dilemmas, another entry point into the consideration of organizational purpose (Albrecht, Varkey, Colville, & Clerkin, 2018; Bull, 2008; McDonald, Weerawardena, Madhavaram, & Mort, 2015; Raišienė & Urmanavičienė, 2017). What this means is that non-profits transitioning into a social enterprise approach may change their underpinning values, beliefs, and systems, which govern how they approach their participants and their communities. Yet, these organizations want to stay true to their social engagement by reconciling the tensions between “social purpose and market” and that this balancing act is how organizations work towards the double-bottom line (Child, Witesman, & Spencer, 2016).

Researchers consider social enterprise typologies as a conceptual approach to orienting how these logics, or more broadly, organization purposes, work within the overall operation of the social enterprise (Besharov & Smith, 2014). Typologies are lenses to explore social enterprise; they provide an entry point into understanding why a social enterprise exists, for what purposes, and the types of operations it conducts to address that purpose. Typologies are a way to show how organizations enact the balance of their core purposes; that is, how these organizations trade to fulfill their purpose (Defourny & Nyssens, 2017). Social enterprises present themselves in many ways, and very differently within the literature, falling under different names, which tend to articulate their purpose.

For example, a WISE is a Work Integrated Social Enterprise. These “employment provider” social enterprises conduct trade for the purpose of providing disadvantaged persons the opportunity to earn an income. It is an enterprise that serves “the low-qualified, long-term unemployed at risk of permanent exclusion from the labor market” by directly employing them to sell goods or services, which further generates revenue for the social enterprise (Woodside, 2018, p. 41). The WISE model, however, is also not a “one size fits all” approach. Our findings show that context also informs WISE typology. In a review of a London-based charity's transition to social enterprise to better support the city's homeless, Leadbeater (2013) noted that “some social enterprise models have a better ‘fit’ for supporting the homeless sector than others” (p. 266). Similarly, drawing on a series of cases in Spain, Salvà and Rosselló (2012) identified two prominent types of WISEs. These are special employment centers and insertion enterprises. A review of Nordic enterprises it is a matter of both name and law. Developing accessible work opportunities must be pursued by those that label themselves “social enterprises” (Pestoff & Hulgård, 2016). In this sense, the WISE is synonymous with social enterprise by law.

Much of the recent scholarship we find considers typologies through the EMES approach. Defourny and Nyssens (2017) suggest that in order to hone our understanding of typologies, we need to consider the stakes and interest in social enterprise. They present these interests across four typologies. These typologies are based on the interest of three stakeholder groups: the specific population (mutual); the broad population (general); or for capital interest. Traditionally, mutuals and cooperatives work for mutual interest, the state and traditional non-profits work for general interest, and a for-profit business works for capital interest. Social enterprises are essentially spin-off organizations of each traditional business by drawing on and incorporating other interests into their business model. The following four typologies represent these spinoffs.

The ENP encompasses traditional non-profits, which derive a trading arm to earn income that will directly support their social programs. They pursue commercial activity alongside traditional non-profit operations and governance to “compliment public grants and donations with new sources of funding” (Defourny & Nyssens, 2017, p. 2481). The Social Cooperative (SC) derives from the traditional cooperative and mutual, which works for the benefit of members by giving members the governance of the organization. The SC also works for general interest, such that their trading activity may benefit a larger development objective. The authors provide the example of a social energy cooperative, which seeks to provide financially accessible energy to its members, but because it pursues renewable energy, it also works towards larger environmental objectives, which benefit the population. The Social Business (SB) draws on capital interest. However, the authors claim that when a for-profit business is instituted by a social entrepreneur, the business actually draws on both capital and general interest because it provides goods or services for the public good. The provision of a good or service is embedded in the business model, and inherently generates general interest no matter the governance structure or profit distribution. For example, a business that provides affordable housing to the elderly or a fair-trade organization.

3.4 Purpose, typology, and S4SC

It is clear that the organizations we work with will face tensions in their underpinning logic. This particular finding illustrates ways to consider these tensions, a notion we find beneficial to our own negotiation. We cannot assume for an organization how they balance rival and corresponding logics and the typology that overarchingly describes their operations. Therefore, we must put it to the organization, offering insight into the potential typologies. Yet, we do find that without fail, both context and the overall creation of social value remain at the core of the enterprises we work with. There is considerable insight within the literature that social enterprise typology is informed by both organizational and community needs.

3.5 Purpose and the external environment

Finally, we find research must consider the inherent challenges in social enterprise despite ongoing consideration of this activity as a tool to face the challenges within the non-profit environment. Therefore, there is a durst of research, which focuses on meeting these challenges—another purpose for us to consider (Herbst, 2019). One scholarly track focuses on the “organizational ecology” in which the social enterprise operates (Searing, Lecy, & Andersson, 2016). In order to meet their purposes, they must operate across multiple stakeholders, a market of participants, customers, funders, and policy officials (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010). Operating in this external environment is based on the organization's strategic position and overall management of knowledge to achieve this position. Strategic position is a business term that describes how the organization distinguishes itself from its competitors (Salavou & Manolopoulos, 2019). The literature tells us that social enterprises increase the business capacity of the organization such that they become more appealing to the external partners and donors (Mikołajczak, 2019). Organizations that transition to social enterprise for this purpose do so to build not only financial capacity, but also human resource, structural and operational capacity for the purpose of fulfilling external relationships and positive social development, factors appealing to others in the organizational ecosystem (Christensen & Gazley, 2008; Eisinger, 2002).

Many scholars also propose that interaction with actors in this ecosystem must be grounded in the cocreation of value. Yet, this can happen in a myriad of ways (Brinkerhoff & Brinkerhoff, 2011; Herbst, 2019; Pulino et al., 2019). One means has already been discussed in our findings. This is the cocreation of a welcoming social enterprise environment at the policy level. In this sense, the social enterprise takes on the role of an advocate or policy influencer given their lived experience. However, Karanda and Toledano (2020) have suggested this remains a challenging space to occupy. Even though the social enterprise provides instrumental insight as a case study to policy reform, many times the policy process is not participatory, limiting the potential for social enterprise advocacy in the space.

Scholars also focus on social enterprises that co-develop strategies with the government and other actors in the organization's ecosystem (Cook, Benson, & Inman, 2014). In one sense, we see social enterprises operating in partnership with governments. Based on the UK definition of social enterprise, these organizations are the “spin outs” of public welfare provision following the retrenchment of public funds (Spear, 2009). Yet, we find in the literature that this discussion resonates across varying contexts. Herbst (2019) illustrates the benefits of government alignment in Australia. Social enterprises that embed their interventions in either government or other institutional strategies have neutralized external threats to their program survivability. Working with higher-degree institutions to develop employment-specific certifications for intervention participants or working with government agencies to subsidize programs that work across product supply chain to create a more circular and environmentally conscious product production provide key examples (Salavou & Manolopoulos, 2019). Not only does this subsidize costs and increase program survivability, production, and delivery of consumer goods and services is grounded in consumer-supported ethos (Herbst, 2019). Thompson, Williams, Kwong, and Thomas (2015) additionally illustrate that many social enterprises, particularly in deprived, rural locales, require subsidization by government funding, despite trading activity. This funding can support organizational costs, but if organizations aim at continuing their program delivery, a funding mix, potentially assumed through partnership, must be achieved.

Ko and Liu (2015) offer the lens of knowledge spillover for further explanation on working in and outside of the organization's direct ecosystem. Knowledge spillover refers to an unintentional flow of knowledge from one member of the ecosystem to another. It is grounded in social interaction. Yet, based on Ko and Liu's findings, this social interaction must be intentional to aid the enterprises survival. It is in the organization's best interest to work with a diversity of actors both in their direct ecosystem and external to it to gain critical knowledge to business management. They should also work in accordance with local experts to understand the community market for their goods and services (Kirkman, 2012). Contrary to this research approach are those that consider actors in this ecosystem as detrimental to the organization core purpose.

Scholars also enter this discussion by focusing on the internal capacities of the organization as key to the organization ecosystem. These capacities drive the strategic position. Peng and Liang (2019), for example, explore the challenges within the transition from non-profit to social enterprise. What they find is creative leadership and staffing are core to the success of this transition. Without this, the social enterprise may remain ambiguous to developing competitive advantage as they remain risk averse rather than pursue the risk associated with social entrepreneurship. In addition, scholarly findings show that those non-profits with integral understanding of the core business of the enterprise will progress the transition (Cho & Sultana, 2015).

3.6 Organization ecosystem, social enterprise, and S4SC

What we find in this specific discussion is the inherent need for potential enterprise to actively engage with their direct and indirect ecosystems to face competitive challenges. This requires clear communication and strategy. We have already concluded that organizations must consider the legal environment in which to operate a social enterprise. Now we find that they may act as advocates towards the creation of this environment by engaging with and working across the key actors in the organizational ecosystem. Actors in the organizational ecosystem are also beneficial to the social enterprise in the transition from community-based non-profit. We must consider moving forward the opportunity in this engagement and how those in the SFW network may consider social enterprise through partnership and interaction with other actors.

4 DISCUSSION

There is clear fluidity across the research concepts and approaches we present in the discussion and our initial conclusions. Therefore, the first thing we must consider in negotiation with the SFW network and the S4SC field is this fluidity. How can we draw across these concepts when negotiating what is a social enterprise within the SFW network? This conclusion is a presentation of the key concepts that researchers in the S4SC field should consider when working alongside S4SC organizations to interpret social enterprise. We contend that this must occur in negotiation with organizations. It is the reason we do not just draw on a single conceptual approach. What is described in the following conclusion is how we as researchers can become informed on social enterprise to enter into these negotiations.

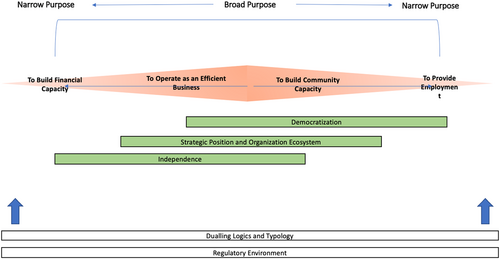

We address this by presenting our own paradigm underpinned in the conclusions we have drawn during the presentation of the literature narrative (see Figure 2). First, we find that there are four broad purposes of social enterprise revealed within the literature. We consider that each purpose is an organization's first consideration of engaging in social enterprise activity. It is based on their context and participant and community needs (Roy et al., 2014). While we find there is a primary purpose, there are additional secondary and tertiary purposes as well (See Figure 2).

Explained from left to right, we first have the purpose to build financial capacity. The organizations we work with face the ongoing challenge of financial sustainability, which hinders their capacity to contribute towards sustainable social development. These organizations have to “remain financially viable” in order to “accomplish their social missions” (Litrico & Besharov, 2019, p. 343). In this context, social enterprise purpose is as a “novel solution” to promote “financial independence” through the generation of their own income (Kirkman, 2012, p. 143). Integral to this process is developing business-like management processes, not only to manage enterprise activity, but to drive greater efficiencies in achieving the original non-profit purpose (Mersha, Sriram, & Elliott, 2014). Moving to the right, organizations transitioning to social enterprise may do so with the purpose to provide employment opportunities to marginalized communities (Woodside, 2018). This can be achieved within the larger purpose, however, of building community capacity. The literature implies that social enterprises are organizations equipped to employ mechanisms that empower their community (Audebrand, 2017; Ng, Leung, & Tsang, 2018).

Integral to each purpose are a series of factors that organizations may address in their transition. These factors may help them articulate or orient their purpose and overall operationalization of social enterprise. For example, we have underpinned “business management,” “employment,” and “capacity building” in democratization. What we find is that the way an organization approaches their human resources can lead to increased employee well-being (Roumpi, Magrizos, & Nicolopoulou, 2020). If an organization considers that either their key or peripheral purpose is to provide employment, then management of their human resources will be integral to their consideration of their social enterprises. What this means is that their enterprising activity does not negatively impact their participants. Democratization is a term that regularly presents itself in conversations on cooperatives, yet is integral to the EMES guidelines, making it relevant across different contextual approaches (Audebrand, 2017; Wagenaar, 2019). Prominently employment of participatory decision-making builds community capacity, reflective of the participatory governance dimension of the EMES definition (Singh & Singh, 2014; Spencer, Brueckner, Wise, & Marika, 2017; Urban & Gaffurini, 2018). Granados and Rivera (2018) suggest a flexible and decentralized structure benefits both employee and the competitive advantage of the organization.

We situate external ecosystem and strategic position underneath “business management.” The literature suggests that organizations must consider their direct and indirect ecosystem. Scholars argue that social enterprise employees are integral to the strategic position of the organization. However, successful social enterprises heavily consider the expertise they may gain from others in the field, such as other social enterprises, and external to it, such as private sector practitioners. Furthermore, when considering purpose, organizations may also consider how their purpose aligns with the interests of those in their ecosystem to develop key partnerships. Given this, we must consider that though organizations seek independence, as evidenced in the next factor, they gain efficiencies through partnership as well (Brinkerhoff & Brinkerhoff, 2011).

We must also credit those scholars who suggest social enterprise is a mechanism for community-based organizations to operate more independently. Yes, this attributes to the financial independence they can gain. However, there are many scholars who still consider social enterprises require a funding mix to support their social missions. What we also mean by independence is independence in program delivery. We find social enterprise is a means for organizations to dictate their programming, rather than in response to donors' needs (Cornforth, 2014).

Underpinning this spectrum are key considerations into how the organization will operationalize their enterprise. This is illustrated by dualling logics and typology and regulatory environment. First, we find it may be inherent for an organization to discuss social enterprise as an ethical challenge to their overall organization. What we mean by this is that the organization may have to consider new values and beliefs, which align to their stated purposes. We find the literature draws on this to articulate how the organization will operationalize their purpose. Therefore, we can negotiate with organizations on how the social enterprise may transpire in their own context based on how they embed or disassociate their social enterprise purpose from their traditional operations (Besharov & Smith, 2014; Defourny & Nyssens, 2017).

We also find in this review that purpose can inform how an organization operates (i.e., typology) but it is also informed by the regulatory environment in which it operates. Therefore, we must consider the context of the organizations we are working with to interpret how they fit in the current regulatory environment. Yet, we must also consider if it is not a welcoming environment, what role can that organization play. We also find that conversation with other organizations may be integral to understanding this environment, further bolstering the need to consider the current organization ecosystem (Ko & Liu, 2015).

5 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

We engaged RAMESES to find the conceptual approaches across social enterprise scholarship associated with social enterprise development within existing community-based non-profits. We did not enter to find new conceptual approaches to social enterprise (Wong et al., 2013). We want to credit the contexts of those who come before us to ensure when we enter negotiation with our study's end-users that we enter with broad insights. This approach is grounded in the Fourth-Generation Evaluation methodological approach to the larger study (Guba & Lincoln, 1989). Therefore, the model we present illustrates the considerations we must make in our own negotiation approach based on the fluidity of concepts and approaches across the literature. Our goal moving forward is to apply this knowledge and build holistic interpretation in our own research and across the S4SC field as scholars such as us in the field aim to contribute understanding and practical application towards the innovation and survival of these organizations (Schulenkorf et al., 2016; Svensson, 2017; Svensson & Cohen, 2020).

This study makes significant contribution to non-profit management research by highlighting a preliminary research process that can be engaged to limit bias. Though the focus to this study regarded the case of S4SC, it is probably the foundation of negotiation appropriate for others in the non-profit space. Non-profit research faces considerable challenges of bias, which can exacerbate non-profit dependency. Even though participatory research is a predominant methodological approach in the non-profit literature, in our experience, studies can still be constrained by existing, preconceived conceptual notion, which may not always reflect the nuances and perceptions of the lived-experience expert, the organization (de Leeuw & Harris-Roxas, 2016).

The findings in this article also reveal opportunity for the community-based non-profit in the S4SC field and beyond. Due to the specificity of our approach to the community-based organization, the model we present provides key information practitioners can use to consider their transition to and/or engagement with social enterprise in their organization. The article has offered key challenges and considerations, which could reflect the diverse contexts of lived experiences across practitioners.

In addition, the article indicates where there may be challenges to social enterprise development including context-specific policy and partnership management. The negotiation approach offered in this article can also be used for practitioners to identify the challenges and opportunities in their direct organization ecosystem. Included in this is also opportunity for negotiation between the practitioner and policy officials and partners. Organizations can use this approach to help them speak to where partners and policy support could bolster their social enterprise development and activities.

Further research in the S4SC field should move to understand and interpret each factor and consideration highlighted in this negotiation process. The more we are able to draw on existing practice and how organizations orient themselves around these factors, the more we are able to support those in the field working towards this organizational model. We also recognize this as a limitation of this current work. It was not within the scope of this review to identify all country-specific regulations, prominent typologies, and core institutional considerations to social enterprise. Rather we take this opportunity to present broad concepts, which may frame the future discussion of SE across the S4SC field. We have therefore presented the “philosophical or cultural position adopted” (Jones & Keaugh, 2006, p. 12) rather than the economic position.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Alex Richmond conceived the concept and presented to Evelyne de Leeuw and Anne Bunde-Birouste. Alex Richmond performed the analysis and developed the narrative and conclusions. Evelyne de Leeuw and Anne Bunde-Birouste supervised the manuscript and contributed to the final version.

ENDNOTE

Biographies

Alex Richmond is a doctoral candidate at the School of Population Health, University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. She has a background in non-profit program development and sustainability, with particular focus to build capacity in the field of Sport for Development and Social Change (S4SC). She is increasingly experienced in fourth generation evaluation, an evaluation protocol designed to put the voice of the stakeholders at the center of research and development challenges. She holds dual B.A/B. S degrees from the University of Georgia, and an MSc. in Sport Management, Policy, and International Development from the University of Edinburgh.

Evelyne de Leeuw is operating at the interface of health research, policy and practice at the University of New South Wales, the South Western Sydney Local Health District/Population Health, and the Ingham Institute. She is the Director of the HUE (Healthy Urban Environments) Collaboratory, a Maridulu Budyari Gumal partnership, run by three universities (UNSW, UTS and WSU) and two large Local Health Districts. She has glocal roles in Healthy Cities development with WHO and several NGOs. She serves on the Board of IUHPE and is active in the scientific health promotion arena, as chair of IUHPE2022, and Editor-in-Chief of Health Promotion International. She (co)leads initiatives to establish a health political science disciplinary effort.

Dr. Anne Bunde-Birouste is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer at the School of Population Health at the University of New South Wales, Professor of Leadership at the international Football Business Academy and a member of the Academic Board of the Australian College of Physical Activity. Anne is internationally recognized for her expertise in health promotion, sport for development and social change, innovative community-based approaches for working with disadvantaged groups. Anne specialises in fostering the nexus between practice-based research, teaching, and social impact. Anne is the Founding Director of Football United (http://footballunited.org.au/), Director of the Creating Chances Social Enterprise (http://creatingchances.org.au/), and an elected member of the Street football world international football for good network, https://www.streetfootballworld.org/

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.