Perceived brand transparency: A conceptualization and measurement scale

Abstract

Amid product scandals, corporate malpractices, and the proliferation of misinformation, consumers are becoming increasingly more skeptical about the brands they purchase. Transparency is often hailed as a strategic imperative to reassure consumers and increase brand trust; however, its deployment can be complex. With additional transparency, consumers may become overloaded with information, and the brand may be exposed to unwanted external scrutiny. Consequently, before disclosing strategically sensitive information, brands need more insight into how increasing transparency might translate into strategically desirable consumers' brand evaluations. Addressing this need, we examine how transparency initiatives translate into consumers' evaluation of brands by delineating the dimensions of the perceived brand transparency construct, namely, observability, comprehensibility, and intentionality. Next, we use this conceptualization to develop and validate a scale to measure perceived brand transparency. We close with a brand transparency research agenda, as well as practical guidance for managers considering investing in strategic transparency initiatives.

1 INTRODUCTION

Aiming to purchase and consume higher quality, safer, and more sustainable market offerings, many consumers seek more transparency from brands (de Ruyter et al., 2022). Reflecting this emerging consumer preference, research by Fashion Revolution (2023), a global fashion industry body, identifies the transparency of product provenance as a critical strategic priority to reassure consumers and regain brand trust. Many brands seek to meet this transparency demand by investing in advanced technological infrastructures (e.g., blockchain) that enable visibility and traceability of brand policies, processes, and governance mechanisms (Plangger et al., 2022).

There is increasing evidence of the strategic use of transparency. Consider, for example, the skincare brand Paula's Choice, which provides a detailed “ingredients dictionary” to ensure that consumers are fully aware of what they put on their skin. Thanks to its commitment to transparency and straightforward communications, the brand is a popular choice among Generation Z consumers and one of the most talked about brands on the social media platform Reddit (Robert, 2021). In the personal data domain, the videoconferencing platform Zoom now provides detailed information on how it handles governments' and enforcement agencies' data requests. By actively embracing transparency, Zoom rebuilt trust with its privacy-concerned users (Barber, 2020). In the sustainability and social responsibility domains, outdoor clothing brand Patagonia openly communicates about the environmental impact of raw materials and manufacturing processes and discloses its strict suppliers' vetting criteria. Transparency allows Patagonia to stand out in a sector characterized by opaque communications on environmental and social sustainability issues (Marquis, 2020).

By placing transparency at the core of their competitive strategy, these brands were able to build long-lasting customer relationships, elicit trust, and create new avenues for differentiation (Keller, 2020; Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020). However, implementing transparency can both increase operational costs and expose brands to leaks of proprietary information, leading to unwanted external scrutiny (Suddaby & Panwar, 2022). Furthermore, consumers can easily become overloaded with information, leading to incomplete processing of the available evidence that, in turn, may hinder decision-making quality and effectiveness (Branco et al., 2016). Thus, despite the promising role that transparency could play as an intangible source of brand differentiation (Keller, 2020), managers are largely unaware of how to assess the effectiveness of transparency initiatives to positively influence how consumers evaluate brands.

How do brands become subjectively perceived as transparent by consumers? Existing studies primarily examine transparency's objective properties, such as information asymmetry reduction (e.g., Simintiras et al., 2015) or information disclosure characteristics and delivery methods (e.g., Chen et al., 2022), instead of assessing how perceived transparency might impact consumers' brand evaluations and decisions. Moreover, unintentionally, several studies conflate transparency with the visibility of a brand's corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts (e.g., Foscht et al., 2018), leading to an overlap between these two constructs. This lack of clarity on the nature of perceived transparency and how it can be applied to brands has led several marketing scholars to adopt ad-hoc definitions and operationalizations (e.g., Cambier & Poncin, 2020). Thus, from both managerial and academic perspectives, there is an urgent need for scholarship that conceptualizes perceived brand transparency and provides a robust measurement instrument to evaluate its effectiveness in academic and industry-led research.

Addressing this need, this research offers two key contributions: (1) a conceptualization of perceived brand transparency, and (2) a validated measure to empirically test this construct's impact on consumers' brand evaluations and purchase intentions. First, guided by theoretical perspectives on transparency, we define perceived brand transparency as the extent to which consumers perceive that a brand provides visibility of how it creates and delivers consumer value, communicates in a straightforward and accessible way, and voluntarily discloses relevant information. Specifically, we conceptualize perceived brand transparency as having three reflective dimensions: value creation and delivery observability, brand message comprehensibility, and information disclosure intentionality. This conceptualization transcends the information-asymmetry view of transparency (e.g., Granados & Gupta, 2013) by both integrating subjective perceptions of the information disclosed and by demonstrating that these perceptions are important to consumers when forming holistic evaluations of brand transparency. Over several studies, we conceptually and empirically demonstrate that perceived brand transparency encompasses a broader set of cognitive associations. Second, we provide a measurement tool of consumers' perceptions of brand transparency that is psychometrically robust across different studies and samples.

In what follows, we combine an assessment of existing transparency scholarship with a preliminary exploratory study to inform our conceptualization of perceived brand transparency. Then, we report the results of six studies designed to build and validate a measurement scale and examine how perceived brand transparency is related to other theoretically relevant constructs. Next, we conclude with an assessment of how perceived brand transparency affects consumers' evaluations and purchase intentions through a final experimental study. We close by discussing academic and practical implications, as well as suggesting a future research agenda.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND: CONCEPTUAL PERSPECTIVES ON TRANSPARENCY

The broader concept of transparency has generated significant interest across a variety of disciplines, including management and leadership (Schnackenberg et al., 2020), operations and supply chain management (Mohr & Thissen, 2022), CSR (Tang & Higgins, 2022), information systems (Granados & Gupta, 2013), and communications (Gibbs et al., 2022). Within the marketing and consumer behavior literature, researchers have focused primarily on empirical investigations of how transparency, in the form of disclosure of information, applies to different marketing and branding strategies (Lambillotte et al., 2022; Totzek & Jurgensen, 2021). The growing number of multidisciplinary contributions largely reflects the promising role that transparency could play as an intangible source of brand value (Keller, 2020).

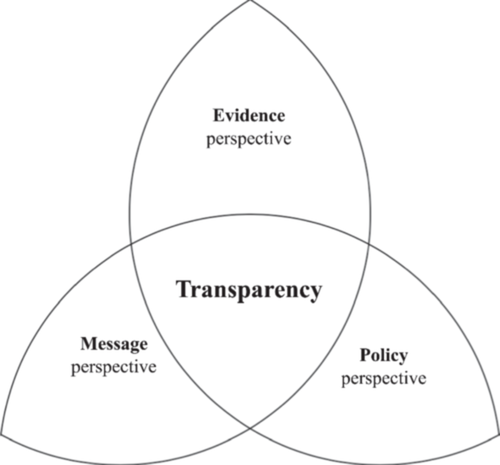

In what follows, we examine how the current literature defines transparency (see Table 1) and identify three perspectives through which transparency can be understood, namely, evidence, information, and policy transparency (see Figure 1). Consistent with these three perspectives, transparency can be extracted from the different stages of the brand value creation process (the evidence perspective), demonstrated through communications that influence stakeholders' evaluations and decisions (the information perspective), and codified into organizational policies and procedures that increase public scrutiny (the policy perspective). These perspectives are not mutually exclusive but represent a set of interconnected conceptual lenses through which transparency can be understood.

| Context | Study | Transparency definition | Dimensions | Transparency perspective | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | I | P | ||||

| Organization and stakeholders' relationships | Eggert and Helm (2003) | “An individual's subjective perception of being informed about the relevant actions and properties of the other party in the interaction” |

|

x | ||

|

||||||

| Hultman and Axelsson (2007) | “The ability to ‘see through’ and to share information that is usually not shared between two businesses” |

|

x | |||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Leitch (2017); Rawlins (2008) | “The deliberate attempt to make available all legally releasable information – whether positive or negative in nature—in a manner that is accurate, timely, balanced, and unequivocal” |

|

x | x | ||

|

||||||

| Schnackenberg et al. (2020) | “The perceived quality of intentionally shared information from a sender” |

|

x | |||

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Tang and Higgins (2022) | “Openness in organizational activities and a willingness to intentionally share information with stakeholders to inform and enhance their decision making” |

|

x' | |||

| Organizational processes and performance | Bernstein (2012) | “Accurate observability of an organization's low-level activities, routines, behaviors, output, and performance” |

|

x | ||

|

||||||

| Liu et al. (2015) | “The extent to which customers view the information provided by firms about their services as accessible and objective” |

|

x | x | ||

|

||||||

| Madhavan (2000) | “The quantity and quality of the information provided to market participants during the trading process” |

|

x | |||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Mohan et al. (2020) | “Firm's disclosure of the costs that the firm incurs to provide a given product or service” |

|

x | |||

| Market transactions | Foscht et al. (2018) | “The offering of critical evaluation about the pros and cons of a business's products/services that are easily accessible to and easily understood by customers” |

|

x | x | |

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Zhou et al. (2018) | “The extent to which consumers could easily access and clearly understand the information needed to evaluate the performance of a product, vendor, and transaction” |

|

x | |||

| Zhu (2002) | “The degree of accessibility and visibility of the information” |

|

x | |||

|

||||||

| Consumer brand perceptions | This article | The extent to which consumers perceive that a brand provides visibility of how it creates and delivers consumer value, communicates in a straightforward and accessible way, and voluntarily discloses relevant information. |

|

x | x | x |

- Abbreviations: E, evidence; I, Information; P, Policy.

2.1 Transparency as evidence

Conceptualizations of transparency, aligned with the evidence perspective, are built upon the assumption that a transparent system can be observed and scrutinized (Bernstein, 2012; Hultman & Axelsson, 2007). As such, evidence-derived transparency allows observers to discover the objective truth about a system and becomes a verification tool that enables control of the system (Mohr & Thissen, 2022). Within this perspective, transparency becomes the mechanism through which internal and external stakeholders can observe and evaluate the activities, performances, and outputs of different organizational processes (Liu et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2018).

Translated to a consumption context, evidence-derived transparency allows consumers to access and evaluate accurate information pertaining to a brand and its products or services in an easy and accessible manner (Foscht et al., 2018). For instance, transparency technologies such as radio-frequency identification (RFID) and blockchain (Bai & Sarkis, 2020) allow consumers to trace product journeys from sourcing to production to commercialization. This kind of transparency can result in product integrity assurance (Saak, 2016), consumer empowerment (Kanagaretnam et al., 2014), and brand trust (Tan & Saraniemi, 2022).

2.2 Transparency as information

Transparency is often conceptualized as a knowledge-sharing mechanism that increases the logic and understandability of information messages (Granados et al., 2010; Lambillotte et al., 2022). Brands that invest in the communication of transparent messages disclose information multilaterally to stakeholders with the aim of keeping them informed and fostering trust-based relationships (Schnackenberg et al., 2020). Conceptualizations of transparency consistent with the information perspective associate transparency with information quantity and quality (Zhou & Zhu, 2010). In this context, transparency lowers information asymmetry between participants in market exchanges, leading to a reduction of uncertainty and improvements in decision quality (Board & Lu, 2018). Information transparency's effectiveness builds upon the assumptions that the disclosed information is comprehensible and that the receiver is sufficiently competent, interested, and involved to process that information (Christensen & Cheney, 2015).

While employees or suppliers might have stronger incentives to process transparency messages (Scheibehenne et al., 2010), consumers are often overwhelmed with information (Branco et al., 2016), lack sufficient motivation (Maclnnis et al., 1991), and regularly rely on heuristics to direct thinking and behavior (Basu et al., 2022). Messages containing new information can be distorted by consumers' pre-existing beliefs (Hernandez & Preston, 2013), leading to message resistance and resulting in biased judgments (Anglin, 2019). Brands must, therefore, calibrate their information disclosure strategies to ensure that consumers process their messages to generate their intended outcomes.

2.3 Transparency as policy

Within the policy perspective, transparency refers to a broad range of organizational practices that increase public scrutiny (Bushman et al., 2004), promote good governance (Christensen & Cheney, 2015), and encourage accountability of decision-makers (Leitch, 2017). Transparency policies can target critical issues relevant to multiple stakeholders, including, for example, pay information disclosure (Brown et al., 2022) or environmental, social, and governance performance (Reber et al., 2022). Transparency in the form of voluntary disclosure signals openness (Leitch, 2017; Rawlins, 2008), mitigates the negative consequences of the information made available outside the firm (e.g., negative financial assessments; Dennis et al., 2019), and elicits credibility and trust (Hogreve et al., 2019). Moreover, successful transparency policies can foster stronger relationships between supply chain partners (Montecchi et al., 2021). By increasing transparency, a partner might experience the perception of being kept informed about the actions and intentions of others, leading to increased trust and commitment (Eggert & Helm, 2003).

Similarly, brands with transparency policies can often enjoy stronger relationships with their consumers, as evidenced by research into CSR practices (Buell & Kalkanci, 2021) and consumer transparency movements (Mol, 2015). Consumers are increasingly concerned with brands' operating practices, including employee diversity and inclusivity commitments (Arsel et al., 2022), working conditions, slavery and human trafficking (Islam & Van Staden, 2022), and local communities engagement (Yuan & Zhang, 2020). Brands with effective transparency policies often voluntarily report environmental and social impacts, as well as outline and plan corrective actions required by regulators and industry bodies (Du et al., 2017).

3 THE DIMENSIONS OF PERCEIVED BRAND TRANSPARENCY: EXPLORATORY STUDY

Through our examination of the broader transparency literature, we identify three interconnected transparency perspectives: evidence, information, and policy. While there is some overlap between these perspectives, our discussion illustrates their distinctive characteristics that encapsulate the multifaceted nature of transparency. By combining conceptual insights derived from these perspectives with an exploratory empirical study, we now further explore how consumers experience transparency in relation to brands.

3.1 Method

This exploratory study included 120 participants recruited through the research crowdsourcing platform Prolific Academic. After excluding incomplete responses, we obtained a final sample of 102 participants involving a 40:60 female/male ratio predominantly aged between 18 and 34 (82.35%). Participants were asked to answer a series of open questions that prompted them to reflect on how transparency might influence how they evaluate brands. The first 20 responses were coded inductively, and the emerging codes were used to analyze the full set of responses through several rounds of data reduction. To check the interpretive validity of these findings, we discussed our preliminary results with 14 experts (a split of academics and doctoral students) in marketing, supply chain, and law. This iterative analysis led to the identification of three dimensions of perceived brand transparency, namely observability, comprehensibility, and intentionality. In the following sections, we discuss these inductively derived insights with reference to the transparency perspectives of evidence, information, and policy identified in the literature (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix A).

3.2 The observability dimension

Participants indicate that transparent brands allow consumers to “see through every aspect and see what they [the brand] are doing right and wrong,” explain “where and how products are made,” and enable an “open dialogue on topics such as manufacturing and sustainability.” As such, consumers directly observe the evidence of value creation and value delivery processes. Several participants mention that transparent brands allow consumers to trace products from material sourcing through to manufacturing and distribution. Some transparent brands provide a detailed breakdown of the costs associated with each stage and explain how these costs contribute to the price paid by the consumer. In line with these findings, we define observability as the extent to which a brand's value creation and value delivery processes can be equated to the products or services associated with the brand.

The observability dimension reflects the evidence perspective that examines the coordination of supply chain visibility strategies and traceability systems to increase transparency (Sodhi & Tang, 2019). By providing observability, transparent brands allow consumers to establish a link between the output of a system (i.e., a brand's product or service) and its inputs and internal workings. The enhanced contextual knowledge that consumers gain through observability can reduce perceived risks (Yoo et al., 2015) and increase their perception of choice control and empowerment (Kanagaretnam et al., 2014).

3.3 The comprehensibility dimension

When asked what makes a brand transparent, several participants stress the importance of clear and understandable brand messages. Transparent brands not only disclose a wealth of information through a series of touchpoints (e.g., advertising, websites, social media platforms), but they also provide information that is “well designed” and expressed “in plain English.” Furthermore, participants note that transparent brands signal a “willingness to explain” the functional and symbolic benefits provided to consumers. In doing so, transparent brands do not exaggerate claims, overpromise benefits, or try to persuade consumers to buy products not worth their real value. Thus, the comprehensibility dimension refers to the extent to which consumers perceive brand messages to be clear, accessible, and easy to process.

The comprehensibility dimension reflects the information perspective that views transparency as the extent of information asymmetry reduction (Madhavan, 2000) and the quality of the information disclosed (Schnackenberg et al., 2020). However, we propose that comprehensibility evaluations in the context of a transparent brand's message exceed the mere information quantity and quality aspects. As comprehensible messages lead to more fluent processing of the information presented (Miele & Molden, 2010), the source is perceived as safer to trust by the receiver (Janiszewski & Meyvis, 2001).

3.4 The intentionality dimension

The intentionality of information disclosure emerges as a prominent characteristic that participants associate with transparent brands. Although firms are required to comply with several regulatory frameworks that mandate the disclosure of information (e.g., financial statements), participants solely regard voluntary disclosures as genuine brand transparency strategies. Transparent brands are seen as “upfront” in their dealings with consumers and attempt to openly address what consumers “would want to know about the brand that would make it more reliable.” Participants' expectations of intentional disclosure involve issues that are becoming increasingly more important to consumers, such as fair pay and working conditions of the “people behind the brand” (e.g., suppliers, factory workers, retail staff), local community engagement, and commitment to environmental sustainability. However, many participants expect brands to engage in intentional disclosure beyond CSR and sustainability issues. Several participants mention that brands have a duty to keep consumers informed throughout the consumption journey. Building on these insights, we conceptualize intentionality as consumers' perception of a brand's deliberate attempt to make information available for public scrutiny.

This dimension is consistent with transparency theoretics in the policy perspective, which highlights how intentional disclosure of organizational commitments toward stakeholders promotes a culture of openness (Walker, 2016) and builds trust-based relationships (Foscht et al., 2018; Tan & Saraniemi, 2022). Furthermore, as consumers often attempt to infer motives behind firms' actions beyond the information that is made readily available to them (Berry et al., 2018), intentionality is likely to reinforce perceptions of the brand's openness, integrity, and honesty.

3.5 Summary: Definition and dimensionality of perceived brand transparency

Perceived brand transparency is the extent to which consumers perceive that a brand provides visibility of how it creates and delivers consumer value (observability), communicates in a straightforward and accessible way (comprehensibility), and voluntarily discloses relevant information (intentionality).

Following guidelines on construct dimensionality specification, we interpret perceived brand transparency as a second-order reflective construct (MacKenzie et al., 2011). First, this formal specification underscores how perceived brand transparency is not merely about information disclosure but rather is the manifestation of multifaceted consumer perceptions encompassed in the three dimensions identified in the exploratory study. Removing any of the dimensions would substantially reduce the conceptual scope of the construct. Second, our earlier examination of the three overarching transparency perspectives (evidence, information, and policy) reveals that while substantially distinct, these perspectives conceptually overlap. Consistent with this theorizing, we expect the dimensions identified in our exploratory study to share a substantial commonality, as brand transparency evaluations are likely to be holistic consumer assessments (Law et al., 1998). In line with these arguments, adopting a latent, multidimensional reflective model enables us to integrate diverse yet related brand transparency perceptions into a unified conceptual entity that explains the common variance between the dimensions (Wong et al., 2008). This type of dimensionality specification is also aligned with other overarching brand constructs that require holistic stakeholder evaluations of comparable complexity (e.g., brand orientation; Piha et al., 2021).

4 MEASURING PERCEIVED BRAND TRANSPARENCY

The construction and validation of a perceived brand transparency scale that captures the identified dimensions of observability, comprehensibility, and intentionality involved seven quantitative studies (see Table 2 for an overview of the studies). We followed MacKenzie et al. (2011) scale development procedures and guidelines from scale development research in the marketing branding domains (e.g., Golossenko et al., 2020; Morhart et al., 2015; Sample et al., 2023). The initial item generation and content validity study (Study 1) is followed by five survey-based studies that include initial dimensionality assessment and item reduction (Study 2), scale refinement and confirmation of dimensionality (Study 3), validation sample (Study 4), discriminant and incremental predictive validity assessments (Study 5), evaluation of the construct in its nomological network (Study 6). We conclude with an experimental study that provides evidence of how perceived brand transparency might influence consumers' brand evaluations and purchase intentions (Study 7).

| Step | Method | Sample(s) | Main results | Additional evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1—Conceptual definition and dimensionality of the perceived brand transparency construct |

|

|

|

|

| Step 2—Scale items generation and item content validity assessment |

|

|

|

– |

| Step 3—Construct initial dimensionality and items reduction. |

|

Study 2 (survey): n = 288 consumers |

|

|

| Step 4—Scale refinement and confirmation of dimensionality |

|

Study 3 (survey): n = 284 consumers Study 4 (survey): n = 591 consumers |

|

|

| Step 5—Discriminant validity, incremental predictive validity, and nomological network |

|

Study 5 (survey): n = 579 consumers Study 6 (survey): n = 596 consumers |

|

|

| Step 6—Experimental validity and effects on behavioral intention |

|

Study 7 (between-subjects experiment): n = 225 consumers |

|

|

- Abbreviations: CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; EFA, exploratory factor analysis.

4.1 Study 1: Scale items development

The objective of Study 1 was to develop an initial set of items to represent the three hypothesized dimensions of perceived brand transparency. We generated a pool of 137 items drawing from the findings of our exploratory study and insights from the transparency perspectives identified in the literature. We also examined existing scales in the general transparency domain (e.g., Rawlins, 2008; Schnackenberg et al., 2020) to evaluate the suitability of some of the items. Although related, these scales were primarily designed to capture employee's perceptions of the transparency of organizational policies. While we decided not to incorporate existing items into the new scale, this step was essential to ensure the initial pool of items captured all the necessary transparency facets already conceptualized in the literature.

Acting as independent judges, three authors conducted an initial screening to evaluate the face validity of each item in relation to the proposed dimensions (average proportion of interjudge agreement = 0.781; Rust & Cooil, 1994). Only items unanimously selected were retained, resulting in a refined set of 39 items after several iterations. Next, a panel of 20 experts (balanced between academics and doctoral students) assessed the content validity of the 39 items by rating on a 5-point scale (1 = low, 5 = high) the extent to which each item captured each dimension of the construct. Before scoring the items, the experts were asked to comment on the proposed conceptualization of perceived brand transparency. The experts were also encouraged to offer feedback on the specific wording of each individual item. Items questioned by raters or that did not yield a statistically significantly higher mean score on the a priori dimension were highlighted for further editing or removal, resulting in a set of 26 items.

4.2 Study 2: Assessment of scale dimensionality and item reduction

Study 2's primary objectives were to explore the factor structure of perceived brand transparency and increase the measure's parsimony with exploratory factor analysis.

4.2.1 Sample and procedure

Through Prolific Academic, this study recruited 361 participants who rated one randomly assigned brand out of four on the 26 items from Study 1 (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree). The four brands were pretested to represent different levels of high (H&M, Lush) and low (Primark, Amazon) brand transparency (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix B for further details on the pretest studies). Participants also rated their level of familiarity with the brand on a three-item scale (Zhou et al., 2010; ⍺ = 0.82). Incomplete responses, responses from participants who did not pass attention and data quality checks, or indicated low brand familiarity (Mbrand familiarity ≤ 2) were removed, resulting in a final sample of 288 participants (female = 66.67%, Mage = 32.09).

We conducted exploratory factor analysis with principal axis factoring as an extraction method in combination with direct Oblimin rotation to account for the expected correlation between the conceptual dimensions of perceived brand transparency. We estimated the number of factors to retain by combining insights from parallel analysis (Hayton et al., 2004), the Kaiser criterion, and visual scree plot analysis. To produce a more parsimonious solution, we examined the factor loadings using cut-off criteria of 0.60 for factor loadings to the primary factor (Golossenko et al., 2020), and 0.32 for cross-loadings (Costello & Osborne, 2005), removing items that did not meet these criteria one at a time. This analysis resulted in a three-factor solution of 15 items consistent with the three hypothesized dimensions of observability, comprehensibility, and intentionality. The substantial correlations between the three dimensions (rint-obs = 0.54, p < 0.001; rint-comp = 0.54, p < 0.001; robs-comp = 0.57, p < 0.001) provide initial evidence of the presence of second-order perceived brand transparency factor, reflected by the three first-order dimensions (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix C for further details). We tested this higher-order factor structure in subsequent studies.

4.3 Study 3: Scale refinement, convergent validity, and confirmation of dimensionality

Study 3's objectives were to (1) further purify the perceived brand transparency scale, (2) examine the scale's convergent validity and internal consistency reliability, and (3) validate its factor structure with confirmatory factor analysis.

4.3.1 Sample and procedures

Through Prolific Academic, we recruited 357 participants who rated one randomly assigned brand out of the six pretested brands (high transparency: The Body Shop, Lush; medium transparency: Adidas, McDonald's; low transparency: Primark, Facebook) on the revised 15 items scale. We excluded participants who provided incomplete responses, did not pass attention and data quality checks, or indicated low levels of brand familiarity (Mbrand Familiarity ≤ 2; Zhou et al., 2010; ⍺ = 0.84), obtaining a sample size of 284 usable responses (female = 50.70%, Mage = 34.53).

4.3.2 Scale refinement

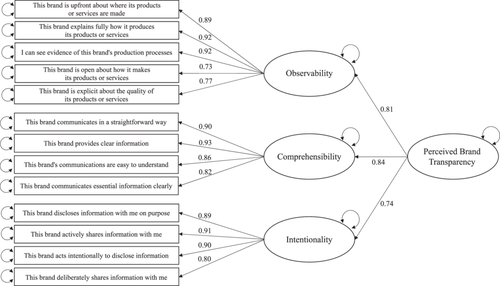

Consistent with Study 2 results, we hypothesize perceived brand transparency as a second-order construct reflected on three dimensions. To test this factor structure, we performed confirmatory factor analysis on a model with three first-order factors accounting for the 15 items identified in Study 2 and one second-order factor. While the analysis produced acceptable results (χ2 = 296.92 (87), p < 0.001; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.95; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.94; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.092; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.073), some fit indexes suggested that the measurement model could be improved. First, we examined the first-order factor loadings (λ) for evidence of nonsignificant or weak relationships (λ2 < 0.50) with the latent constructs (MacKenzie et al., 2011). We removed one item with a square standardized factor loading score below 0.50. Next, we examined the modification indexes and excluded one item accounting for a single high modification index (>30; Golossenko et al., 2020). Finally, we examined a revised model with the remaining 13 items using confirmatory factor analysis. Table 3 results indicate an improvement in the overall model fit (χ2 = 167.41 (62), p < 0.001; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.077; SRMR = 0.038).

| Study 3 | Study 4 | Study 5 | Study 6 | Study 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 284 | 591 | 579 | 596 | 225 |

| Number of items | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Model fit indexes | |||||

| χ2 (df) | 167.41 (62) | 231.12 (62) | 258.19 (62) | 208.43 (62) | 161.79 (62) |

| CFI | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| TLI | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| RMSEA | 0.077 | 0.068 | 0.074 | 0.063 | 0.084 |

| SRMR | 0.038 | 0.040 | 0.041 | 0.039 | 0.059 |

| First-order: Factor loadings (λ)a | |||||

| Observability | 0.81–0.93 | 0.73–0.92 | 0.74–0.95 | 0.75–0.91 | 0.61–0.93 |

| Comprehensibility | 0.84–0.94 | 0.82–0.93 | 0.83–0.92 | 0.78–0.90 | 0.86–0.93 |

| Intentionality | 0.75–0.91 | 0.80–0.91 | 0.85–0.93 | 0.83–0.92 | 0.85–0.93 |

| First-order: AVE; CR; Cronbach's ⍺ | |||||

| Observability | 0.77; 0.94; 0.94 | 0.72; 0.93; 0.93 | 0.75; 0.93; 0.93 | 0.70; 0.92; 0.92 | 0.70; 0.93; 0.91 |

| Comprehensibility | 0.81; 0.94; 0.94 | 0.77; 0.93; 0.93 | 0.79; 0.94; 0.94 | 0.71; 0.91; 0.90 | 0.83; 0.95; 0.95 |

| Intentionality | 0.75; 0.92; 0.92 | 0.77; 0.93; 0.93 | 0.82; 0.95; 0.95 | 0.77; 0.93; 0.93 | 0.77; 0.93; 0.93 |

| Second-order: Factor loadings (γ)a | |||||

| Observability | 0.94 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Comprehensibility | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.7 |

| Intentionality | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.82 |

| Second-order: AVE; CLVR | 0.65; 0.84 | 0.63; 0.84 | 0.61;0.82 | 0.60; 0.82 | 0.65; 0.85 |

- Note: For the CFI and the TLI, values above 0.90 and close to 0.95 are considered good indication of model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For the RMSEA and the SRMR, values below 0.08 are considered acceptable by most researchers (Golossenko et al., 2020; Schnackenberg et al., 2020).

- Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; CFI, comparative fit index; CLVR, composite latent variable reliability; CR, composite reliability; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index.

- a Factor loadings are reported completely standardized. All factor loadings are significant at p < 0.001.

4.3.3 Construct validation

We examined the convergent validity and internal consistency reliability of the scale. Average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach's coefficient ⍺ scores for the first-order factors met the threshold values (see Table 3; AVE > 0.5, ⍺ > 0.7, CR > 0.7). At the second-order level, the AVE (=0.65) also exceeded the recommended 0.50 threshold, suggesting that the second-order perceived brand transparency factor accounts for the majority of the variance of the first-order dimensions (MacKenzie et al., 2011). Overall, Study 3 results provide evidence of the convergent validity and internal consistency reliability of the proposed scale.

4.3.4 Confirmation of construct dimensionality

We validated the dimensionality of the perceived brand transparency construct by comparing the hypothesized second-order factor structure with alternative models consisting of different combinations of the three first-order factors, and with a model in which all items were loaded onto a single perceived brand transparency factor (Golossenko et al., 2020). To compare the alternative models, we examined fit indexes, χ2 differences (Δχ2), comparative fit index differences (ΔCFI), and Akaike information criterion (AIC) differences (Δi). We expected the hypothesized model to exhibit greater fit, as well as significant and positive Δχ2 (Schnackenberg et al., 2020), ΔCFI > 0.01 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), and Δi (ΔAIC) > 2 (Burnham & Anderson, 2004). The results of multiple comparisons (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix D) confirmed our expectations, indicating that our hypothesized second-order factor model outperformed alternative models on all comparison criteria considered.

4.3.5 Known-groups comparisons

To assess the content validity of the scale, we averaged the 13 items and performed a series of comparisons (MacKenzie et al., 2011; Morhart et al., 2015) between brands representing expected variations of perceived brand transparency (high: The Body Shop, Lush; medium: Adidas, McDonald's; low: Primark, Facebook). We anticipated that brands in the high-transparency group would score significantly higher on the proposed perceived brand transparency scale. Overall, the results2 confirmed our predictions, providing support to the anticipated systematic variations of the scale.

4.4 Study 4: Validation sample and final dimensionality assessment

As some items were removed or partially modified due to Study 3,3 we designed Study 4 with the primary objective of validating the final version scale on a new sample. In this study, we also established measurement invariance of the perceived brand transparency scale with respect to gender.

4.4.1 Sample and procedures

From Prolific Academic, this study recruited 659 participants who rated the perceived brand transparency of one randomly assigned brand out of three pretested brands (high: The Body Shop; medium: McDonald's; low: Primark). After removing participants who provided incomplete responses, did not pass attention and quality checks, or had indicated low brand familiarity (Mbrand Familiarity ≤ 2; Zhou et al., 2010; ⍺ = 0.72), we obtained a final sample size of 591 (female = 63.60%; Mage = 31.70).

4.4.2 Validation sample

We examined our hypothesized model of three first-order factors and one second-order factor (see Figure 2) with confirmatory factor analysis. The model had an appropriate level of fit (χ2 = 231.12 (62), p < 0.001; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.068; SRMR = 0.040), and all scale items loaded significantly to the expected first-order factors with standardized loadings (λ) ranging from 0.73 to 0.93. The first-order dimensions loaded significantly to the higher-order perceived brand transparency factor, with second-order standardized loadings (γ) ranging from 0.74 to 0.84 (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix E for further details).

4.4.3 Test of measurement invariance

In Study 4, we tested the invariance of the second-order perceived brand transparency construct in relation to gender. We selected gender for invariance testing as the variable is often used in marketing research studies (Golossenko et al., 2020). As we do not envisage any theoretically plausible reason for brand transparency perceptions to differ between men and women, it is important to verify if our scale produces consistent measures for these two groups. Following Rudnev et al.'s (2018) guidelines for testing measurement invariance of second-order latent factors, we examined several nested models through multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. The different models were compared by testing χ2 differences and by examining deteriorations of model fit. Specifically, we examined ΔCFI and accepted models exhibiting a change in CFI smaller than 0.01 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Overall, the results of multiple model comparisons provide strong support to the measurement invariance of the perceived brand transparency scale in relation to gender (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix E for further details).

4.5 Study 5: Discriminant validity and incremental predictive validity

Study 5 examined the discriminant validity of the perceived brand transparency scale when compared to scales designed to measure related yet conceptually different constructs in the broader transparency domain. The study also examined the ability of perceived brand transparency to adequately predict relevant criterion variables, including brand attitude, brand trust, positive word of mouth, and purchase intention.

4.5.1 Sample and procedure

From Prolific Academic, this study recruited 664 participants who rated one randomly allocated brand out of six pretested brands (The Body Shop, McDonald's, Adidas, Ikea, Coca-Cola, and Primark) on measures of brand attitude (Sengupta & Johar, 2002; ⍺ = 0.92), brand trust (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; ⍺ = 0.89), word of mouth likelihood (Alexandrov et al., 2013; ⍺ = 0.96) and purchase intention (De Vries & Duque, 2018, ⍺ = 0.97). Next, participants evaluated the assigned brand on the 13-item perceived brand transparency scale, and on five related constructs, including performance transparency (Liu et al., 2015, ⍺ = 0.80), product transparency (Zhou et al., 2018; ⍺ = 0.97), vendor transparency (Zhou et al., 2018; ⍺ = 0.97), information transparency (Schnackenberg et al., 2020; ⍺ = 0.96), and organization reputation for transparency (Rawlins, 2008; ⍺ = 0.94). We assessed all transparency-related constructs for convergent validity and internal consistency reliability (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix F for further details on the measurements used in Study 5). Following the approach employed in the previous studies, we removed participants who provided incomplete responses, did not pass the attention and quality checks, or indicated low brand familiarity (Mbrand Familiarity ≤ 2; Zhou et al., 2010; ⍺ = 0.74), obtaining a final sample size of 579 (female = 49.9%, Mage = 40.86).

4.5.2 Discriminant validity

Results of confirmatory factor analysis for a model with three first-order dimensions and one second-order perceived brand transparency factor revealed a good level of fit (Table 3), consistent with the results of studies 3 and 4 (χ2 = 258.19 (62), p < 0.001; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.075; SRMR = 0.041). First, we assessed the discriminant validity of perceived brand transparency by adopting the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion that requires the AVE of each construct to exceed the square correlation coefficient between the pair of constructs considered. Table 4 results show that the AVE scores of perceived brand transparency were consistently higher than the square correlation coefficient with each construct, thus meeting the recommended threshold for discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

| Construct | CR | AVE | Square correlation coefficients (r2)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1. Perceived brand transparency | 0.82b | 0.60 | – | ||||

| 2. Performance transparency | 0.82 | 0.56 | 0.45 | – | |||

| 3. Product transparency | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.27 | 0.29 | – | ||

| 4. Vendor transparency | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.48 | – | |

| 5. Information transparency | 0.90b | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.31 | |

| 6. Organization reputation for transparency | 0.85 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.52 |

- Note: n = 579.

- Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; CR, composite reliability.

- a All correlations are significant at p < 0.001.

- b For perceived brand transparency and information transparency, we report the composite latent variable reliability score.

4.5.3 Incremental predictive validity

Following Kinicki et al.'s (2013) approach, we conducted a usefulness analysis to evaluate how perceived brand transparency accounts for incremental variance in brand attitude, brand trust, positive word of mouth, and purchase intention, above the variance accounted by the other constructs considered. Although these constructs are conceptually related as they represent different aspects of the broader transparency domain, we expect that perceived brand transparency will significantly improve the prediction of the four criterion variables. To test the predictive contribution of perceived brand transparency, we estimated several hierarchical regression models by entering the related constructs in the first step and perceived brand transparency in the second step. Next, we compared these results to reverse models estimated by entering perceived brand transparency as the first predictor.

Results indicate that including perceived brand transparency as the second stage significantly increases the R2 in all hierarchical regression models when predicting brand attitude (ΔR2: 0.03–0.28, p < 0.001), brand trust (ΔR2: 0.05–0.30, p < 0.001), word of mouth (ΔR2: 0.02–0.19, p < 0.001), and purchase intent (ΔR2: 0.01, p < 0.01–0.09, p < 0.001). When perceived brand transparency is entered in the first stage, the reverse models predict a significant amount of variance in brand attitude (R2 = 0.40, p < 0.001), brand trust (R2 = 0.42, p < 0.001), word of mouth (R2 = 0.27, p < 0.001), and purchase intent (R2 = 0.14, p < 0.001). Taken together, these results provide evidence of the incremental predictive validity of the perceived brand transparency scale (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix F for details).

4.6 Study 6: Assessment of perceived brand transparency nomological network

Study 6 assesses the broader nomological validity of the perceived brand transparency construct by examining its relationships with other conceptually relevant constructs. To this end, we examined how perceived brand transparency is positively related to brand credibility, brand integrity, brand authenticity, and brand CSR. For completeness, we also re-assessed the relationship between perceived brand transparency and brand trust, given the central role that the latter plays in explaining how brand transparency might influence behaviors (Woisetschläger et al., 2017). Before presenting the results of Study 6, we discuss the theoretical justifications for the hypothesized relationships.

Brand credibility is a composite brand evaluation based on consumers' perceptions of the brand's willingness (trustworthiness) and ability (expertise) to fulfill its promises (Erdem & Swait, 2004). In the presence of information asymmetry, consumers form perceptions of credibility by using cues manipulated by the brand (Yazdanparast & Kukar-Kinney, 2023). These cues help them to build a schematic image of the brand and to decide whether brand claims are believable or not (Meyvis & Janiszewski, 2004). Transparent brands enable consumers to observe how the products and services that the brand contains create and deliver value, communicate brand messages and policies in a comprehensible manner, and intentionally disclose relevant information. The perceived brand transparency dimensions operate as highly diagnostic cues that enhance the believability of a brand's claim, thus triggering a mental image of a “credible entity.” Formally, we propose:

H1.Perceived brand transparency is positively related to brand credibility.

Brand integrity refers to a holistic brand characteristic that integrates desirable qualities such as adherence to codes of practice, alignment between words and actions, and responsibility (Grewal et al., 1998). Overt brand promises of functional and symbolic performances become a psychological contract between the consumers and the brand (Davis & Rothstein, 2006). Driven by a need for consistency (Russo et al., 2008), consumers will expect the brand to fulfill this contract by behaving in a manner coherent with marketing claims, internal policies, and quality standards. By providing insights into these inner workings, transparency allows consumers to verify the extent to which the brand meets its obligations and to hold the brand responsible for its actions. Therefore, we predict that:

H2.Perceived brand transparency is positively related to brand integrity.

Brand authenticity can be conceptualized as the extent to which consumers perceive that a brand corresponds to certain standards. In the eyes of consumers, judged against these standards, authentic brands stay true to their history and heritage, are accurate about claims of originality, and prioritize the integrity of their market offerings over short-term commercial gains (Moulard et al., 2021). While some brands can live up to these standards, others fabricate perceptions of authenticity by focusing on the more salient authenticity cues (e.g., “made in…”). By allowing consumers to visualize the brand's inputs and outputs, transparency cues reduce potential contradictions and conflicting signals, thus reinforcing perceptions of authenticity (Fritz, Schöggl, et al., 2017). Consequently, we anticipate that:

H3.Perceived brand transparency is positively related to brand authenticity.

Perceived brand transparency is also conceptually related to brand CSR, which reflects consumers' perceptions of a brand's fairness and adherence to sound principles that benefit consumers and society at large (Grohmann & Bodur, 2015). Establishing transparency strategies when implementing CSR policies is of paramount importance to reduce consumers' and other stakeholders' skepticism (Buell & Kalkanci, 2021), increase internal and external engagement (Sen et al., 2023), and ultimately avoid accusations of green-washing (Wu et al., 2020). However, while many brand transparency strategies involve CSR communication, brands can signal transparency by revealing other aspects of their value creation that are relevant to the consumer (e.g., origin, certification of authenticity, or pricing). As such, transparent brands intentionally disclose credible and diagnostic information that enhances consumers' “reasons to believe” marketing claims beyond the narrower scope of CSR disclosures (Batra & Keller, 2016). It is, therefore, essential to examine the extent to which brand transparency and brand CSR are conceptually related yet different constructs. In line with these arguments, we propose:

H4.Perceived brand transparency is positively related to brand CSR.

Brand trust refers to consumers' willingness to rely on a brand's ability to deliver the expected benefits (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). Brands that are transparent mitigate consumers' perceived risks by reducing the uncertainty associated with the expected functional or symbolic benefits that the brand provides. As the choice process is simplified, consumers are likely to experience transparent brands and their communications as clearer, more honest, and ultimately safer to trust. Furthermore, through transparency, brands can signal openness and altruistic motives (Woisetschläger et al., 2017), thus reinforcing consumers' trust perceptions. Based on these considerations, we predict that:

H5.Perceived brand transparency is positively related to brand trust.

4.6.1 Sample, procedures, and measurements

From Prolific Academic, this study recruited 660 participants who evaluated one randomly assigned brand out of six pretested brands (The Body Shop, McDonald's, Adidas, Ikea, Coca-Cola, and Primark) on the 13-item perceived brand transparency scale. We used established scales to measure brand credibility (Erdem & Swait, 2004; expertise ⍺ = 0.82, trustworthiness ⍺ = 0.91), brand integrity (Cambier & Poncin, 2020; ⍺ = 0.77), brand authenticity (Fritz, Schöggl, et al., 2017; ⍺ = 0.95), and brand trust (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; ⍺ = 0.89). Brand CSR was measured by employing two scales—brand social responsibility beliefs (Grohmann & Bodur, 2015; ⍺ = 0.93) and brand ethics (Mpinganjira & Maduku, 2019; ⍺ = 0.94), in an effort to capture different aspects of this multifaceted construct. All constructs were measured on 7-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) and assessed for convergent validity and internal consistency with confirmatory factor analysis (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix G for further details of Study 6). Following the same procedure used in Studies 2–5, we removed participants who provided incomplete responses, did not pass attention and data quality checks, or indicated low levels of brand familiarity (Mbrand Familiarity ≤ 2; Zhou et al., 2010; ⍺ = 0.68), obtaining a final sample size of 596 (female = 73.3%, Mage = 33.31).

4.6.2 Results

Results of a confirmatory factor analysis for a model with three first-order dimensions and one second-order perceived brand transparency factor revealed a good level of fit, consistent with the results of the previous studies (χ2 = 208.43 (62), p < 0.001; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.063; SRMR = 0.039). First, following the same approach implemented in Study 5, we examined the discriminant validity of perceived brand transparency by adopting the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion. Table 5 results indicate that the AVE scores for perceived brand transparency consistently exceeded the square correlation coefficient with each construct considered in the study, thus satisfying the recommended threshold for discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

| Construct | CR | AVE | Square correlation coefficients (r2)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| 1. Perceived brand transparency | 0.81b | 0.60 | |||||||

| 2. Brand credibility—expertise | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.32 | ||||||

| 3. Brand credibility—trustworthiness | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.54 | |||||

| 4. Brand integrity | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.55 | ||||

| 5. Brand authenticity | 0.92 | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 0.57 | |||

| 6. Brand CSR—CSR beliefs | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.51 | ||

| 7. Brand CSR—ethics | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.59 | |

| 8. Brand trust | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.65 |

- Note: n = 596.

- Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; CR, composite reliability; CSR, corporate social responsibility.

- a All correlations are significant at p < 0.001.

- b For perceived brand transparency, we report the composite latent variable reliability score.

Next, we tested the hypothesized relationships between perceived brand transparency and each of the variables considered with structural equation modeling using maximum likelihood as the estimation method. The overall measurement model provided a good level of fit (χ2 = 3188.04 (1092), p < 0.001; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.057; SRMR = 0.052), and the structural model coefficients indicated that perceived brand transparency positively relates to the expertise (β = 0.70, p < 0.001) and trustworthiness (β = 0.76, p < 0.001) dimensions of brand credibility, as well as to brand integrity (β = 0.82, p < 0.001), brand authenticity (β = 0.82, p < 0.001), brand CSR (ethics: β = 0.80, p < 0.001; CSR beliefs: β = 0.80, p < 0.001), and brand trust (β = 0.82, p < 0.001). Overall, these results confirmed the hypothesized relationships (H1–H5), offering further evidence of nomological validity of the construct within its identified nomological network.

4.7 Study 7: Experimental validity—Effects on consumer purchase intentions

Study 7 evaluated the effects of perceived brand transparency on consumer brand evaluations and purchase intention. In doing so, we provide evidence of the scale's experimental validity. We begin by discussing the hypothesized direct and indirect effects of perceived brand transparency on purchase intention. Then, we outline the experimental procedure designed to test these effects and report Study 7 results.

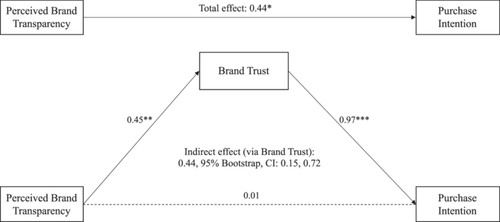

Perceived brand transparency likely has a positive effect on consumers' purchase intention toward brands. Incomplete information between buyers and sellers leads to an increase in the uncertainty of the outcome of a market transaction (Shulman et al., 2015). As the possibility of a loss appears (i.e., the brand might not deliver on its expected benefits), consumer uncertainty increases, which can negatively impact the likelihood of purchase (Verhagen et al., 2006). By reducing information asymmetry, brand transparency mitigates the perceived risks induced by transaction uncertainty, thus leading to an increase in purchase intention. Therefore, we propose:

H6.Higher (vs. lower) perceived brand transparency positively influences purchase intention toward the brand.

In the presence of asymmetric information, consumers might also be anxious about sellers' opportunistic behaviors (Reeder et al., 2004), such as overplaying symbolic benefits, hiding potential drawbacks, or misrepresenting transaction collaterals (e.g., refund policies or warranties). Brands that are perceived as transparent counteract consumers' attributions of opportunistic behaviors by allowing consumers to observe and verify brand claims, communicating in a comprehensible and accessible manner, and intentionally keeping consumers informed. We expect consumers to interpret transparency as a signal that the brand is trustworthy and genuinely committed to satisfying their needs, likely leading to increases in consumer brand trust evaluations and, subsequently, positive purchase intention. Based on these arguments, we propose:

H7.Increased perceived transparency positively affects purchase intention toward the brand by positively influencing brand trust.

4.7.1 Participants, design, and procedures

From Prolific Academic, 258 participants took part in a between-subjects experiment with two conditions (high vs. low perceived brand transparency). We excluded participants who provided incomplete responses or did not pass attention and data quality checks, obtaining a final sample size of 225 participants (female = 50.7%; Mage = 40.91). The experimental manipulation involved participants watching a promotional video describing a fictitious fashion brand. Participants were randomly allocated to one of two alternative versions of the video that were purposely edited to trigger perceptions of high or low brand transparency across its three dimensions (see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix H for details).

We varied the observability dimension by adding a description of additional details provided by the brand, such as production location, supplier names, and material used (high perceived brand transparency) or more standard details that customers would expect to find (low perceived brand transparency). We varied intentionality by describing investments in brand traceability to keep consumers informed (high perceived brand transparency) or investments in marketing campaigns to reach the target market more effectively (low perceived brand transparency). We varied comprehensibility by describing several options for customers to access and process transparency (high perceived brand transparency) or more typical channels such as store associates (low perceived brand transparency). We chose a fictitious brand to control for the potential confounding effects of pre-existing consumer attitudes associated with real brands.

4.7.2 Measures

We measured perceived brand transparency on the 13-item scale. Results of confirmatory factor analysis revealed a satisfactory level of fit (χ2 = 161.15 (62), p < 0.001; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.084; SRMR = 0.059), convergent validity (AVE = 0.65) and internal consistency reliability (composite latent variable reliability = 0.85) of the scale. We assessed brand trust on a four-item, 7-point Likert scale (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; ⍺ = 0.89), and purchase intention toward the brand on five-item, 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; De Vries & Duque, 2018, ⍺ = 0.97).

4.7.3 Manipulations checks

The manipulation performed as expected, with participants in the high transparency condition reporting higher perceived brand transparency ratings (MHigh = 5.94, MLow = 5.09; t(223) = −7.26, p < 0.001). To further check the accuracy of our manipulation, we compared the two conditions on the mean ratings of the three perceived brand transparency dimensions of observability (α = 0.91), comprehensibility (α = 0.95), and intentionality (α = 0.93). All comparisons indicated that the manipulation was also effective at the level of the individual dimensions of perceived brand transparency (observability: Mhigh = 5.92, Mlow = 4.59; t(223) = −9.218, p < 0.001; comprehensibility: Mhigh = 5.94, Mlow = 5.55; t(223) = −2.948, p = 0.004; intentionality: Mhigh = 5.98, Mlow = 5.28; t(223) = −5.54, p < 0.001).

4.7.4 Results

Results of an independent sample t test revealed a significant effect of perceived brand transparency on consumer purchase intention toward the brand (Mpurchase intention high transparency = 5.06, Mpurchase intention low transparency = 5.50; t(223) = −2.23, p = 0.026), thus providing empirical support for H6. Consistent with our expectations, participants in the high perceived brand transparency condition exhibited significantly more positive purchase intention for the brand described in the promotional video.

We tested the hypothesized indirect effect by using the PROCESS macro Model 4 with bias-corrected bootstrapping and 5000 subsamples (Hayes, 2018). The analysis revealed a significant indirect effect of perceived brand transparency on purchase intent via brand trust (d = 0.44, 95% bootstrap, confidence interval: 0.15, 0.72). In the presence of this mediation, the direct effect was not statistically significant (b = 0.01, p = 0.964), thus providing evidence of full mediation (see Figure 3). Overall, the mediation analysis results confirmed the hypothesized indirect effect via brand trust (H7; see Supporting Information S1: Web Appendix H for further details).

5 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Attempting to address increasing consumer skepticism about the honesty and accountability of marketing claims, many brands have implemented objective transparency strategies that decrease information asymmetry between the brand and customers to mitigate purchase or consumption uncertainty. By combining the three transparency perspectives (evidence, information, and policy) derived from adjacent literatures and extended through an exploratory study, we theorize that consumers use observability, comprehensibility, and intentionality cues to form holistic perceptions of brand transparency. Guided by this novel conceptualization, through seven quantitative studies, we develop and validate a 13-item measure of perceived brand transparency. Our conceptualization of perceived brand transparency, together with the empirical evidence reported above, has substantive implications for marketing researchers and practitioners, as detailed below.

5.1 Theoretical implications and research contributions

Researchers exploring transparency strategies in marketing and consumer behavior can implement both the conceptual and methodological contributions of this article in tandem. First, building on an examination of three conceptual perspectives within which the transparency of an object can exist, our novel conceptualization of perceived brand transparency identifies three reflective dimensions, namely observability, comprehensibly, and intentionality, that delineate how consumers form holistic and subjective perceptions of a brand's transparency. By integrating these subjective perceptions, our conceptualization enhances the information quantity and quality perception of transparency that is predominant in the extant literature (c.f., Madhavan, 2000; Zhu, 2002). Furthermore, we differentiate perceived brand transparency in a nomological network that integrates related, yet distinct brand intangibles (Keller, 2020), such as consumer perceptions of a brand's integrity (Mayer & Davis, 1999), authenticity (Fritz, Schoenmueller, et al., 2017), or CSR (Grohmann & Bodur, 2015; Mpinganjira & Maduku, 2019). Specifically, while CSR initiatives can be the target of some transparency strategies (Buell & Kalkanci, 2021), our central proposition is that consumers form perceptions of brand transparency from a wider set of observability, comprehensibility, and intentionality cues. Moreover, we demonstrate that perceived brand transparency elicits brand trust evaluations, leading to positive purchase intentions toward a brand that is perceived as transparent. These findings extend our understanding of the relationship between transparency and trust by providing conceptual and empirical support to the mechanism through which perceived brand transparency operates (Schnackenberg et al., 2020; Tan & Saraniemi, 2022).

Second, empirically actioning this conceptualization, we develop a measure of perceived brand transparency that reflects the observability, intentionality, and comprehensibility dimensions. Following a robust scale development process (MacKenzie et al., 2011), we validate a 13-item scale that allows marketing researchers to assess consumers' perceptions of brand transparency either by measuring the extent of these perceptions (Studies 3-6) or by assuring researchers of the success of their experimental manipulations (Study 7).

5.2 Managerial implications

Many marketing and brand managers struggle to understand or meet consumer demands for transparency, and, to some extent, to convince executives of the value of directing resources to transparency. We demonstrate how investments in objective transparency initiatives could be translated into consumer-subjective brand transparency perceptions. Three managerial implications emerge from our research: (1) a strategic roadmap for transparency initiatives, (2) transparency positioning, and (3) a perceived brand transparency assessment tool (see Table 6 for a summary of main managerial implications).

| Managerial implications | Suggested managerial guidance | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| A strategic roadmap for transparency initiatives |

|

|

| Transparency positioning |

|

|

| A perceived transparency assessment tool |

|

|

First, the three dimensions of perceived brand transparency offer a strategic roadmap when considering investing in objective transparency initiatives by ensuring sufficient attention is devoted to observability, comprehensibility, and intentionality. Observability requires managers to coordinate with supply chain partners' leading to enhanced traceability and increased visibility that provide consumers with enhanced access to accurate and relevant information. For example, jewelry brand Brilliant Earth (BrilliantEarth.com) has partnered with the technology company Everledger (Everledger.io) to offer full traceability and visibility of the diamond lifecycle using blockchain. Thus, Brilliant Earth's customers can readily observe a diamond's origin, authenticity, custody, and integrity directly through the brand's digital store. Comprehensibility necessitates managers to communicate specific product benefits in the hope that consumers associate this information with their brand and its market positioning. Consider Southwest Airlines' advertising campaigns that have concentrated on consumer fairness (i.e., transparency) by focusing on funny, easy-to-process claims that set service expectations, such as “no hidden fee zone,” “reward seats are only available on days ending in ‘y’,” and “yes, we actually want you to use your points.” Intentionality demands that managers provide easy-to-access, relevant brand information beyond what they would expect to find in the public domain or required to do so by law. For example, Coca-Cola works with Smart Labels (smartlabel.org) to provide additional information (e.g., ingredients sourcing, sustainability compliance, or usage instructions) that is easily accessible using a QR code, thus exceeding consumers' information expectations and increasing intentionality perceptions. Taken together, brand managers can optimize their investments in transparency initiatives to maximize perceived brand transparency by illustrating how the brand provides observable, comprehensible, and intentional information.

Second, as our findings indicate, transparency perceptions can potentially generate new differentiation avenues and reinforce the brand's unique positioning and competitive advantage. While there is an ecological and social sustainability imperative for brands to improve the impact of their operations (de Ruyter et al., 2022), a sustainability brand positioning is not necessarily desirable for all brands due to the potential negative effects of this type of positioning, including reduced enjoyment, satisfaction, value perceptions, and increased negative emotions (Acuti et al., 2022). Brand transparency strategies have the potential to meet this sustainable imperative and minimize divergence from entrenched brand positionings that have been successful previously in communicating the brand's value to consumers.

Third, our scale provides managers with a robust assessment tool to evaluate how transparency translates into desirable brand perceptions. While managerial guidelines on what constitutes product or corporate-level objective transparency exist (e.g., the Fashion Transparency Index), for the most part, these guidelines do not take into consideration consumers' subjective evaluations of transparency, or instead focus on CSR and sustainability perceptions. Our scale provides marketing managers with a new and valuable tool to monitor consumers' holistic brand transparency perceptions. This scale not only enables managers to measure the extent to which consumers recognize the value of initiatives designed to increase the transparency of a brand but also to benchmark their efforts against key competitors to identify areas that need further development.

6 DEVELOPING FUTURE RESEARCH ON PERCEIVED BRAND TRANSPARENCY

While this paper has examined the dimensions of the perceived brand transparency construct and delineated its immediate nomological relationships, many critical future research avenues could extend our initial understanding of the construct. In what follows, we delineate how future research could examine critical antecedents, mediators, and moderators of perceived brand transparency to better understand the construct's broader nomological network and offer a more nuanced investigation of its effects on consumer behavior.

First, further scrutiny of perceived brand transparency antecedents would extend the theoretical understanding of the construct and enhance its managerial relevance. To this end, future research should examine how objective (e.g., presence of certifications or seals) or subjective (e.g., brand messages focused on the country of origin or manufacturing) cues might contribute to the formation of brand transparency perceptions. Cue utilization frameworks (e.g., Rao & Monroe, 1988) and semiotic perspectives that examine indexical and iconic brand cues (e.g., Grayson & Martinec, 2004) can provide suitable conceptual lenses to underpin these investigations.

Second, other critical mediators beyond trust could help explain the mechanisms through which perceived brand transparency influences consumers' evaluations and decisions. Beyond reducing information asymmetry and mitigating consumers' sense of vulnerability toward the brand (Martin et al., 2017), transparency initiatives can influence consumers by triggering their interpretative orientation (Friestad & Wright, 1994). According to attribution theory (Heider, 1958; Kelley, 1967, 1973), individuals are naturally motivated to interpret and explain the social world by inferring the underlying causes of the events and behaviors that they experience. Translated into a consumption context, attribution theory can explain consumers' tendency to infer motives behind a brand's actions beyond the information that is available to them. For example, consumers infer extra service efforts when retailers display products neatly, and this attribution translates into a higher willingness to pay (Morales, 2005). In a similar vein, given the association between brand transparency, integrity, and ethical brand perceptions (Cambier & Poncin, 2020), initiatives that signal a brand's intent to be transparent can trigger inferences of altruistic motives (i.e., the firm cares for consumers and society). When consumers' brand perceptions change from self-interest (i.e., the brand is focused solely on making profits) to social good (i.e., the brand cares about consumers and the broader society), the shift could lead to revised consumers' morality judgments toward the brand (Campbell & Winterich, 2018). These inferences and judgments can potentially mediate the effects that perceived brand transparency might have on consumers' evaluations and decisions.

Third, while our results provide initial evidence of the direct and indirect effects of perceived brand transparency on consumer behavioral intention, we do not test the boundary conditions of these effects. In some circumstances, consumers might not want to know all the details about the brands that they purchase or consume. For example, learning that their favorite brand is not ethically sourced would likely trigger negative psychological consequences (e.g., cognitive dissonance) and increase decision complexity by forcing consumers to deal with painful decision trade-offs (Paharia et al., 2013). In these instances, the anticipation of regret from knowing could force consumers into a state of deliberate ignorance (Gigerenzer & Garcia-Retamero, 2017), which could interfere with the processing of brand transparency signals. Further research should examine the trade-off between consumers' desire for brand transparency and the activation of mental processes that lead to deliberate ignorance to help managers identify the appropriate level of transparency that brands should deploy. Furthermore, future studies could examine if presenting specific transparency signals at different stages of the consumer journey can influence consumers' likelihood of processing these signals. While strategically delaying the flow of relevant brand information could increase initial curiosity, consumers might feel deceived by a lack of brand transparency in the early stages of the journey. These perceptual tradeoffs between transparency, curiosity, and deliberate ignorance represent promising future research directions to better understand how brand transparency might influence consumers.

Fourth, accounting for relevant consumer characteristics would enable future researchers to better understand the nuances of perceived brand transparency effects on consumer behavior. For example, consumers' ability to process communication messages, or need for cognition could be plausible moderators predicted by information processing and persuasion theories (Cacioppo et al., 2018). Personality traits such as openness to new experiences (Schwaba et al., 2018) or cognitive tendencies such as skepticism (Leonidou & Skarmeas, 2017) could change consumers' susceptibility to brand transparency messages. Furthermore, an increasing number of consumers are becoming aware of wider social and environmental issues associated with consumption and embracing marketplace activism (e.g., brand boycotts) (Romani et al., 2015). A focused examination of consumer activist groups could shed light on the extent to which brand transparency could mitigate the negative effects of brand wrongdoings.

This discussion of potential areas of future research inspired us to offer research questions for researchers to expand our understanding of perceived brand transparency nomological network and downstream effects on consumers' brand evaluations and purchase decisions (see Table 7).

| Research theme | Potential research questions |

|---|---|

| Antecedents |

|

| Mediators |

|

| Moderators |

|

| Consumer characteristics |

|

7 CONCLUSIONS

7.1 Research limitations

As with most social science research, this paper is not immune from limitations. At the conceptual level, while we theorize and test several relationships between perceived brand transparency and other conceptually related constructs, an exhaustive mapping of the construct's broader nomological network is outside the scope of a single research project. To partially address these limitations, we have provided a future-looking research agenda (see Table 7 and associated discussion) to guide researchers in examining the broader nomological network of perceived brand transparency. At the empirical level, our studies are based on a sample of pretested brands that respondents evaluated on the perceived brand transparency scale. While we believe this sample is sufficiently comprehensive to provide initial evidence of the scale's validity and reliability, extending the investigation to a broader set of brands could offer more insights into its psychometric properties. Finally, in this research, we focus solely on consumers and examine how this specific stakeholder group forms evaluations of brand transparency. In line with this research aim, we have conceptualized the construct as consumers' perceptions of brand transparency. While these findings are promising, further examinations of how other relevant stakeholder groups (e.g., investors, employees) form brand transparency perceptions, could reveal new insights on this construct.

7.2 Concluding thoughts