Bilioenteric Reconstruction Techniques in Pediatric Living Donor Liver Transplantation

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abstract

Biliary complications (BCs) are still a major cause of morbidity following liver transplantation despite the advancements in the surgical technique. Although Roux-en-Y (RY) hepaticojejunostomy has been the standard technique for years in pediatric patients, there is a limited number of reports on the feasibility of duct-to-duct (DD) anastomosis, and those reports have controversial outcomes. With the largest number of patients ever reported on the topic, this study aims to discuss the feasibility of the DD biliary reconstruction technique in pediatric living donor liver transplantation (LDLT). After the exclusion of the patients with biliary atresia, patients who received either deceased donor or right lobe grafts, and retransplantation patients, data from 154 pediatric LDLTs were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were grouped according to the applied biliary reconstruction technique, and the groups were compared using BCs as the outcome. The overall BC rate was 13% (n = 20), and the groups showed no significant difference (P = 0.6). Stricture was more frequent in the DD reconstruction group; however, this was not statistically significant (P = 0.6). The rate of bile leak was also similar in both groups (P = 0.6). The results show that the DD reconstruction technique can achieve similar outcomes when compared with RY anastomosis. Because DD reconstruction is a more physiological way of establishing bilioenteric integrity, it can safely be applied.

Abbreviations

-

- BA

-

- biliary atresia

-

- BC

-

- biliary complication

-

- DD

-

- duct-to-duct

-

- ERCP

-

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

-

- LDLT

-

- living donor liver transplantation

-

- LLS

-

- left lateral segment

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- PDS

-

- polydioxanone sutures

-

- PELD

-

- Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- PFIC

-

- progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

-

- PTC

-

- percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography

-

- RY

-

- Roux-en-Y

Great advances have been achieved by means of patient management and outcomes in the field of pediatric liver transplantation (LT) because the availability of grafts expanded dramatically with living donor liver transplantation (LDLT), especially in the last 2 decades.(1-3) However, biliary problems remain a major cause of morbidity, and the preferred method of biliary reconstruction is still under debate. Moreover, biliary complications (BCs) seem to be encountered more often with partial liver grafts.(4, 5) Although Roux-en-Y (RY) hepaticojejunostomy has been the standard technique for years, there is a limited number of reports on the feasibility of duct-to-duct (DD) anastomosis, and those reports have controversial outcomes.(6-11)

The advantages of DD anastomosis over RY reconstruction have not been proven in pediatric LT yet, and studies comparing both techniques are limited in terms of patient volume.(12, 13)

Therefore, this study aims to determine the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of DD biliary anastomosis among a relatively larger number of pediatric LT recipients in comparison to RY reconstruction.

Patients and Method

Patient Characteristics

A database search through the recordings of 1097 consecutive LTs from June 2009 to February 2020 was conducted. From a total number of 307 pediatric LTs, the outcomes of 154 patients transplanted with left-sided allografts from living donors were retrospectively analyzed after the exclusion of 71 patients with biliary atresia (BA), 26 patients who received grafts from deceased donors, 34 right lobe liver graft recipients, 18 patients with early mortality, and 8 patients who received a retransplantation. The study was exempt from ethics committee approval due to its retrospective design. All the patients’ informed consents were obtained before the surgery. The patients were then divided into 2 major groups according to the type of biliary reconstruction. The DD reconstruction (n = 112) was employed almost 3 times more frequently than the RY reconstruction (n = 42).

Demographics as well as disease-related data, number of bile ducts, graft and reconstruction types, type of BC (bile leak and stricture), and the time elapsed from the date of transplantation to the diagnosis of BC were recorded for each patient.

Bile leak was defined as a bilirubin concentration in the drain fluid at least 3 times the serum bilirubin concentration on or after postoperative day 3 or if a radiologic or operative intervention for a bile collection or bile peritonitis was required.(14) Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the patient population.

| Variable | DD Group (n = 112) | RY Group (n = 42) | Population (n = 154) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 4.2 (0.29-17) | 1.9 (0.08-14) | 3.5 (0.08-17) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 58 (51.8) | 24 (57.1) | 82 (53.2) | |

| Female | 54 (48.2) | 18 (42.9) | 72 (46.8) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Acute liver failure | 27 (24.1) | 1 (2.4) | 28 (18.2) | |

| PFIC | 16 (14.3) | 9 (21.4) | 25 (16.2) | |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 13 (11.6) | 10 (23.8) | 23 (14.9) | |

| Chronic liver failure | 7 (6.3) | 8 (19) | 15 (9.7) | |

| Hepatoblastoma | 13 (10.9) | 1 (2.4) | 14 (9.1) | |

| Tyrosinemia | 10 (8.9) | 1 (2.4) | 11 (7.1) | |

| Other | 26 (23.2) | 12 (28.6) | 38 (24.7) | |

| PELD score | 17.6 (−11 to 47) | 23.7 (−6 to 44) | 19.3 (−11 to 47) | 0.01 |

| Child score | 8.7 (4-15) | 9.9 (4-15) | 9.1 (4-15) | 0.01 |

| Weight, kg | 16.3 (4-55) | 9.8 (3.5-44) | 14.6 (3.5-55) | <0.001 |

| Graft type | ||||

| LLS | 79 (70.5) | 23 (54.8) | 102 (66.2) | 0.08 |

| Reduced LLS | 10 (8.9) | 16 (38.1) | 26 (16.9) | <0.01 |

| Extended LLS | 9 (8) | 2 (4.8) | 11 (7.1) | 0.5 |

| Left lobe | 14 (12.5) | 1 (2.4) | 15 (9.7) | 0.07 |

| GRWR, % | 1.94 (0.64-4) | 2.62 (0.8-5) | 2.3 (0.64-5) | <0.001 |

| Number of graft bile ducts | 0.06 | |||

| 1 duct | 86 (76.8) | 38 (90.5) | 124 (80.5) | |

| 2 ducts | 26 (23.2) | 4 (9.5) | 30 (19.5) | |

| Number of anastomoses | 1 | |||

| 1 anastomosis | 100 (89.3) | 38 (90.5) | 138 (89.6) | |

| 2 anastomoses | 12 (10.7) | 4 (9.5) | 16 (10.4) | |

| BCs | 16 (14.3) | 4 (9.5) | 20 (13) | 0.6 |

| Bile leak | 3 (2.7) | — | 3 (1.9) | 0.6 |

| Stricture | 15 (13.4) | 4 (9.5) | 19 (12.3) | 0.6 |

| BC incidence in <10 kg patients | 8 (25) | 2 (6) | 10 (15.4) | 0.03 |

| Preferred treatment | ||||

| Operative treatment | 13 (11.6) | — | 13 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Minimally invasive procedures* | 13 (11.6) | 4 (9.5) | 17 (11) | 1 |

| Observation only | 2 (1.7) | — | 2 (1.3) | 1 |

| Time to complication, months | 15.3 (0-62) | 26.5 (0-100) | 21.5 (0-100) | 0.25 |

| Follow-up, months | 81.3 (12-128) | 80.2 (12-128) | 81 (12-128) | 0.47 |

NOTE:

- Data are given as n (%) or median (range).

- * Percutaneous and/or endoscopic biliary drainage procedures.

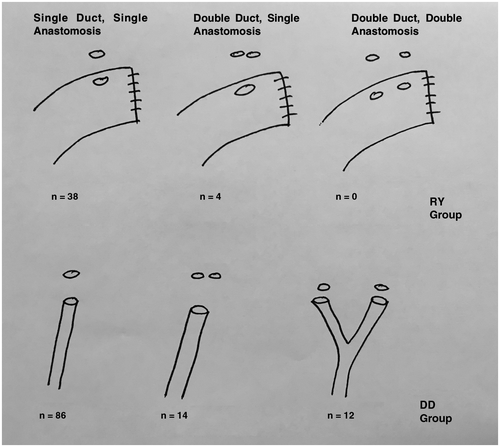

The total number of bile graft bile ducts and number of anastomoses performed were similar between the groups. The majority of the grafts had a single bile duct (n = 124). The biliary reconstruction of 30 grafts with multiple bile ducts was either achieved through a single anastomosis or separate anastomoses, which were performed whenever necessary. Figure 1 schematically demonstrates the types of biliary reconstructions applied.

The mean age was 3.5 years (range, 1 month to 17 years), the mean weight was 14.5 kg (range, 3.5-55 kg), and the mean Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease (PELD) score was 19.3 (range, 11-47). See Table 1 for details.

Donors and the Donor Operation

Donor hepatectomy was performed according to the technique previously described.(15) The bile duct of the graft was cut sharply with scissors at the end of parenchymal transection. Electrocautery was avoided around the bile ducts, and a sharp dissection was preferred without extensive dissection. Intraoperative cholangiography was not routinely used. After harvesting, the liver segment was weighed, and the liver was perfused via the left portal vein with histidine tryptophan ketoglutarate solution.

There was no mortality among the 154 donors in this series. One of the donors (0.6%) experienced grade 3 complication according to the classification by Clavien et al.,(16) which was a reoperation for postoperative hemorrhage and required 2 units of packed red blood cells. This donor recovered uneventfully afterward and was discharged home on postoperative day 7. Minor complications, all grade 1, occurred in 15 (9.7%) donors: fever and atelectasis in 12 patients, gastric dilatation in 2 patients, and neuropraxia in 1 patient. Overall donor morbidity was 7.2%.

Recipient Operation

The recipient total hepatectomy was performed according to classical techniques, preserving the inferior vena cava. The recipient bile duct was not dissected to preserve the blood supply as much as possible and was divided above the bifurcation of the right and left hepatic ducts in most patients. The graft was reperfused after completion of the portal vein anastomosis, and the microsurgical reconstruction of the hepatic artery was subsequently performed.

DD anastomosis was the procedure of choice for all patients meeting the following conditions: <2-fold size discrepancy between the ducts and multiple ducts <1 cm apart allowing for 2 separate anastomoses. The diameter of the duct itself did not affect the decision on anastomosis type.

The bifurcation of the right and left hepatic ducts were unified as a branch patch to achieve a greater circumference of duct size in some of the recipients.

In 86 patients, the left hepatic duct was single, and a single anastomosis between the graft’s duct and the recipient’s common hepatic duct was established. In 14 patients, the graft ducts were double-barrel shaped, and they were close enough to permit a single anastomosis. However, in the remaining 12 patients, the distance between the 2 separate ducts did not allow for a single anastomosis, thus 2 separate anastomoses were performed. DD anastomoses were performed using interrupted 6/0 or 7/0 polydioxanone sutures (PDS) between the recipient’s common hepatic duct and the donor’s left hepatic duct. Either the common hepatic duct or the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts was used for reconstruction on the recipient site. The stitches were tied outside the lumen of the anastomosis. No internal or external stents or catheters were employed in any kind of DD anastomoses.

In the RY group, bile duct reconstructions were performed through a RY limb of the jejunum using interrupted 6/0 or 7/0 PDS. A single anastomosis was performed between the graft duct and the jejunum in all but 4 patients (see Table 1). The stitches were tied outside the lumen of the anastomosis except one to secure the internal stent. After completing the posterior row, a 3-to-4-cm length of a 4 or 5 Fr silastic feeding tube was inserted through the anastomosis and tied, and then the anterior row was completed.

The liver graft was placed to line up with the natural position of the left side of the vena cava, and the round ligament was additionally fixed to the anterior abdominal wall to prevent possible vascular torsion of the graft hilum. All patients received ABO-identical or ABO-compatible grafts from the donors. Prophylactic antibiotics were routinely used. Postoperative immunosuppressive regimen consisted of tacrolimus and steroids in most patients, and mycophenolate mofetil was added to the regimen when needed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was made using SPSS, version 25.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used for the comparison of categorical data, and analysis of variance was performed for continuous parametric variables. Cox regression was used for covariate analysis. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Recipient Complications and Outcome

The patients were followed up for an average of 81 months (range, 12-128 months). None of the recipients in either group experienced hepatic artery thrombosis, and portal vein thrombosis was observed in only 1 patient in the RY group.

The average PELD score was 19.3, and the mean PELD score was significantly higher in the patients in the RY group (P = 0.01). However, the PELD score also did not affect the outcomes significantly (P = 0.23) when tested as a covariate.

The number of anastomoses performed was not significantly different among the groups (P = 1) even though the number of grafts with multiple bile ducts was higher in the DD group (P = 0.06). Neither the number of ducts on the graft nor the number of anastomoses performed significantly altered the outcomes (both P = 1).

The overall rate of BC in the patient population was 13% (n = 20), and there was no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.59). Considering the significant age difference between the patient groups, the rate of BC among the groups was tested using age and weight as a covariate. There was no significant difference by means of BC between those age-adjusted groups (P = 0.1).

The Cox regression analysis of the individual groups revealed that the recipient weight was an independent risk factor predicting BC only for the patients in the DD group (P = 0.02). No other correlation of any type was found for any variable in either of the groups. The subgroup of patients weighing <10 kg in both groups were further compared with the remaining patients of the same group by means of BC occurrence. The patients weighing <10 kg had significantly higher rates of BC in the DD group (n = 32 of 112, P = 0.04); however, this was not valid for the RY group (n = 33 of 42, P = 0.25). Moreover, when these patients were compared between DD and RY groups, the patients weighing <10 kg in the DD group had a significantly higher rate of BC than similar patients in the RY group (P = 0.03). It is important to note that because the number of patients weighing <10 kg was small and the number of BC events was even smaller, a Yate’s correction of this comparison retrieved a P value of 0.07.

When the complications were individually compared as either bile leak or stricture, stricture was more frequent in the DD group, though this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.59).

In the DD group, strictures were mainly corrected by conversion of the anastomoses to a RY reconstruction in 13 of the 15 patients. Bilioenteric continuity was successfully established in all of these 13 patients. The average age and weight of the children experiencing this complication were 2.2 years and 10.8 kg, respectively. The remaining 2 patients were observed with mild stricture because these patients had normal liver function tests without any signs of cholangitis. In the RY group, strictures were managed by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) and balloon dilation in 4 patients.

The patients in the DD group were more likely (P < 0.001) to undergo operative treatment than the patients in the RY group. However, the rate of minimally invasive procedures showed no significant difference among the groups (P = 1).

There were 3 bile leaks in the DD group, which were managed mainly by conservative treatment. Bile leaks were not encountered in the RY group, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.56). See Table 1 for the preferred treatment modalities.

Lastly, the average time from LT to the diagnosis of complication was 21.5 months, and the groups showed no significant difference on this parameter (P = 0.25).

Discussion

BCs are one of the leading causes of postoperative complications in pediatric LT. Although the overall rate was documented to be approximately 15% in large series,(1, 3) there are studies reporting rates of as low as 6% and as high as 38% in the literature.(17, 18) Since the description of biliary anastomosis as the Achilles’ heel of LT by Sir Roy Calne,(19) the complications related to the bile ducts are still the most important technical cause of morbidity following LDLT.

Anastomotic bile leaks and strictures, stent or t-tube problems, and nonanastomotic strictures or bilomas are among the possible BCs following LT. Subsequently, these complications may lead to cholangitis, sepsis, and graft failure and even to retransplantation or patient death.

Surgical technique, anatomical variations, duration of the cold ischemia time, quality of the arterial supply of the donor, and recipient bile ducts and immunological factors are considered as the possible causes of BCs.(13) Despite advances and refinements in surgical technique, relatively shorter cold ischemia times, and perfection of the hepatic arterial reconstruction with microsurgery, BCs are still frequent.

Although DD anastomosis eventually has become the alternative method of biliary reconstruction in adult right lobe LT, this transition has not been widely transferred to pediatric LT.(7, 20, 21) Nonetheless, there are great differences between adult and pediatric LT, such as the dominance of BA among children and technical difficulties due to the smaller size of the bile ducts, especially in children with lower body weight. These are the main restrictions against DD reconstruction.

On the other hand, DD biliary reconstruction is a physiological and quicker method for preserving physiological bilioenteric continuity. Thus, the reflux of intestinal content into the bile ducts and the higher risk of ascending cholangitis as well as the delay in bowel movements due to the intestinal anastomosis are eliminated. Roux limb–related complications, such as bleeding from the enteral anastomosis or mechanical bowel obstruction, are also avoided. Moreover, DD anastomosis allows easy access via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) although the applicability depends on the size and age of the patient. Studies have demonstrated that the arterial supply to the duct is mainly in axial fashion by the periductal arterial plexus,(22) and concerns regarding the vascularization of the recipient’s common hepatic duct are no longer an issue as the method is well established in right lobe LDLT.(20, 21, 23)

There are only a few reports about utilization of DD anastomosis among children, though they show conflicting results in a restricted number of patients. In the series reported by Sakamoto et al. among 19 patients reconstructed via DD, 47% of patients experienced complications and 26% patients were converted to RY.(9) The technique was referred to as challenging but feasible in selected cases. In another series from Taiwan, 7 patients were reconstructed via DD, and 3 of them were converted to RY with 1 bile leak, resulting in a complication rate of 57%, whereas the technique was referred to as feasible in selected cases.(8) In another series from Japan, the technique of DD reconstruction was employed on 14 patients. The overall complication rate was found to be 35%, and the procedure was not found to be preferable over RY reconstruction.(7)

Another report from Canada by Laurence et al. also favored RY over DD reconstruction by means of BC. Although the number of patients is high, this report compares results from an inhomogeneous type of graft from both living and deceased donors. Moreover, the RY reconstruction was not shown to be superior over DD among partial grafts.(13)

There are also very few reports in favor of DD reconstruction. Haberal et al. from Turkey reported their experience of 32 children reconstructed with DD anastomosis, and the BC rate was found to be 16% with results that were found to be safe and feasible.(11) A Japanese group from Kumamoto first published their experience on 6 patients with a complication rate of 16%. Then they reported their experience among 10 patients weighing <10 kg, and the complication rate was found to be 10%, which was not statistically different from the RY group.(10)

This is the highest volume study so far comparing the outcomes of DD reconstruction with RY in a pediatric patient population.

The overall BC rate was not significantly different among the 2 groups in this series nor were the individual complication types, namely, stricture and leak. However, the management of the strictures differed among the groups as the patients in the DD group were more likely to be managed with operative measures (P < 0.001) as instrumentation with ERCP would be hazardous on such small bile ducts. Thus, operative conversion to RY was the treatment of choice after decompression by PTC. Although the higher rate of operative management in the DD group can be considered as a drawback at first glance, RY reconstruction still remains as a second alternative in this subgroup of patients.

Among 154 patients, 112 of them were reconstructed with DD resulting in a rate of 73% feasibility. A size discrepancy that is more frequently encountered in younger patients with lower body weights may have led to a selection bias in which these patients tended to be treated with a RY anastomosis. DD reconstruction could not be employed in a total of 42 patients mainly for anatomical reasons, such as having a very small caliber bile duct or 2 distant bile orifices. In the DD group, there were 32 patients weighing <10 kg, which also demonstrates that this technique is also feasible in small children. However, BCs were significantly higher in this group when compared with the patients weighing <10 kg in the RY group (P = 0.03).

The use of various kinds of stents is another ongoing discussion in LDLT practice. Using a transanastomotic stent may help to decrease the anastomotic pressure by draining bile outside. However, stenting of the bile ducts through the cystic duct or via an opening in the common bile duct may cause further complications. We did not prefer to use stents for DD reconstruction because the caliber of the bile ducts was very small and stenting would be difficult. We believe further studies are needed to compare the results with or without stents in pediatric patients.

In conclusion, DD anastomosis is a safe and feasible method of biliary reconstruction in pediatric LDLT. It seems to be an easier and safer technique by preserving physiological bilioenteric continuity in comparison to RY reconstruction. Accordingly, our findings indicate that DD biliary reconstruction can be the method of choice for pediatric patients with suitable bile ducts for reconstruction.