Should we still offer split-liver transplantation for two adult recipients? A retrospective study of our experience†

See Editorial on Page 919

Abstract

The role of split-liver transplantation (SLT) for two adult recipients is still a matter of debate, and no agreement exists on indications, surgical techniques, and results. The aim of this study was to retrospectively analyze the outcome of our series of SLT. From May 1999 to December 2006, 16 patients underwent SLT at our unit. We used 9 full right grafts (segments 5-8) and 7 full left grafts (segments 1-4). The splitting procedure was always carried out in situ with a fully perfused liver. Postoperative complications were recorded in 8 (50%) patients: 5 (55%) in full right grafts and 3 (43%) in full left grafts. No one was retransplanted. After a median follow-up of 55.82 months (range, 0.4-91.2), 5 (31%) patients died, and the 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rate for patients and grafts was 69%. We considered as a control group for the global outcome 232 whole liver transplantations performed at our unit in the same period of time. Postoperative complications were recorded in 53 (23%) patients, and after a median follow-up of 57.37 months (mean, 55.11; range, 1-102.83), the 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall patient survival was 87%, 82%, and 80%, respectively. In conclusion, SLT for two adult recipients is a technically demanding procedure that requires complex logistics and surgical teams experienced in both liver resection and transplantation. Although the reported rate of survival might be adequate for such a procedure, more efforts have to be made to improve the short-term outcome, which is inadequate in our opinion. The true feasibility of SLT for two adults has to be considered as still under investigation. Liver Transpl 14:999–1006, 2008. © 2008 AASLD.

The use of marginal grafts or extended criteria for deceased donor selection and the use of partial liver grafts have been proposed to expand the donor pool and to reduce the mortality rate for patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation, which has been reported to be up to 20% according to the United Network for Organ Sharing and the European Liver Transplant Registry data.1-4 Largely on the basis of the encouraging results of split-liver transplantation (SLT) in the pediatric population, SLT for two adult recipients has been promoted by some centers. However, despite the theoretical benefits of this procedure in reducing mortality for patients on the waiting list, SLT for two adults is still a matter of debate. Indeed, approximately 100 cases have been reported worldwide so far, and no agreement exists on indications, surgical techniques, and results.5-15 We here describe our experience with SLT for two adult recipients, focusing on indications, surgical technique, and results.

Abbreviations

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; EAD, early allograft dysfunction; FLG, full left graft(s); FRG, full right graft(s); GRWR, graft-to-recipient weight ratio; HAT, hepatic artery thrombosis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; HVT, hepatic vein thrombosis; ICU, intensive care unit; IVC, inferior vena cava; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MHV, middle hepatic vein; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; SLT, split-liver transplantation; TIPSS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We reviewed the records of 16 consecutive patients who underwent SLT for two adult recipients at our unit between May 1999 and December 2006. The complete demographic, clinical, surgical, and pathologic characteristics were recorded in a dedicated and prospectively maintained institutional liver transplantation database.

Donor Selection

The criteria to select donors for SLT were as follows: young age (less than 50 years old), stable hemodynamic conditions with minimal use of inotropic drugs, intensive care unit stay shorter than 1 week, normal or minimally abnormal blood tests, and no macroscopic evidence of steatosis. Liver biopsy was not routinely performed for this purpose.

Eleven deceased donors were considered for graft harvesting to perform SLT. According to Couinaud's classification of liver anatomy, among the 16 split-liver transplants, 9 (56%) were full right grafts (FRG; segments 5-8), and 7 (44%) were full left grafts (FLG; segments 1-4).16 Of the remaining 6 contralateral grafts (2 FRG and 4 FLG), 1 was not used because of operative damage to the right hepatic vein, and 5 were transplanted in other centers according to our program for organ sharing.17 Donors were 7 (64%) men and 4 (36%) women. The median age was 28 years (range, 20-46 years). The median body weight was 82 kg (range, 65-97 kg). The FRG and FLG median weights were 786 (range, 712-860 g) and 568 g (range, 480-610 g), respectively. Table 1 shows the donor characteristics.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of donors | 11 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 7 (64%) |

| Female | 4 (36%) |

| Age (years): median; range | 28; 20-46 |

| Body weight (kg): median; range | 82; 65-97 |

| FRG weight (g): median; range | 786; 712-860 |

| FLG weight (g): median; range | 568; 480-610 |

| ICU stay (days): median; range | 2.45; 1-10 |

| Laboratories | |

| AST (U/L): median; range | 53; 10-108 |

| Peak of serum sodium (mEq/L): median; range | 148; 138-160 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL): median; range | 1.6; 0.4-3.8 |

| Vasopressor (dopamine) | |

| <5 μg/kg/min | 8 (73%) |

| >5 and <10 μg/kg/min | 3 (27%) |

| Cause of death | |

| Trauma | 9 (82%) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 1 (9%) |

| Edema post-neurosurgery | 1 (9%) |

- NOTE: The values in the table are numbers of patients (percentages) unless otherwise specified.

- Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; FLG, full left graft; FRG, full right graft; ICU, intensive care unit.

Recipient Selection

Recipients were on the waiting list for liver transplantation, and they followed the usual selection process for that surgical procedure. However, they were selected for SLT on the basis of the donor-recipient size match and absence of relevant clinically evident portal hypertension. A thorough informed consent was obtained from each recipient, who was fully informed about SLT. They were 5 (31%) men and 11 (69%) women. The median age was 49.3 years (range, 44-59 years) for the FRG and 48.2 years (range, 32-61 years) for the FLG. The median body weight was 65.2 kg (range, 61-76 kg) for the FRG and 62.4 kg (range, 56-74 kg) for the FLG. The median graft-to-recipient body weight ratio was 0.84% (range, 0.72-1.12%) in FRG and 0.82% (range, 0.76-1.04%) in FLG. The median cold ischemic time was 410 minutes (range, 124-760 minutes) for the FRG and 460 minutes (range, 360-780) for the FLG. Table 2 shows the recipients characteristics and their indications for liver transplantation.

| Variable | Full Right Graft | Full Left Graft |

|---|---|---|

| Number of recipients | 9 (56%) | 7 (44%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 3 (33%) | 2 (29%) |

| Female | 6 (67%) | 5 (71%) |

| Age (years): median; range | 49.3; 44-59 | 48.2; 32-61 |

| Body weight (kg): median; range | 65.2; 61-76 | 62,4; 56-74 |

| GRWR (%): median; range | 0.84; 0.72-1.12 | 0.82; 0.76-1.04 |

| Cold ischemia time (minutes): median; range | 410; 124-760 | 460; 360-780 |

| TIPSS | 1 (11%) | 1 (14%) |

| MELD: median; range | 21.5; 15-35 | 20; 10-21 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | — | 1 (14%) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| HCC in HCV cirrhosis | — | 1 |

| HCC in HCV/HBV cirrhosis | 1 (11%) | — |

| HCV cirrhosis | 2 (22%) | 2 (29%) |

| HBV cirrhosis | 2 (22%) | 0 |

| HBV/HDV cirrhosis | 1 (11%) | 0 |

| HBV + alcoholic cirrhosis | 1 (11%) | 0 |

| HCV + PBC + alcoholic cirrhosis | 1 (11%) | 0 |

| Wilson's disease | — | 1 (14%) |

| Primary hyperoxaluria | 1 (11%) | 0 |

| PBC | — | 2 (29%) |

| Caroli's disease | — | 1 (14%) |

- NOTE: The values in the table are numbers of patients (percentages) unless otherwise specified.

- Abbreviations: GRWR, graft-to-recipient weight ratio; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; TIPSS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Surgical Technique

Before any splitting technique, a careful evaluation of the macroscopic appearance of the liver should be carried out to confirm the feasibility of SLT. Then, a standard technique for abdominal organ procurement is initially applied.18

In all cases, the splitting procedure was carried out in situ with a fully perfused liver during multiorgan recovery at the donor institution. Imaging techniques, such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, angiography, or intraoperative cholangiography, were not performed. However, we scanned the liver before the split with intraoperative ultrasound to verify the quality of the liver and to map the middle hepatic vein (MHV) on the liver surface. The resection plane was defined both by the intraoperative ultrasound and by the parenchymal demarcation obtained by the clamping of the right hepatic artery and right portal vein at the hepatic hilum. Thus, we marked the line of parenchymal transection just a few millimeters from the right side of the MHV, and we started the liver parenchymal transection, which was accomplished with the Kelly crush technique, electrocautery, 4/0 monofilament sutures, and metallic clips. The intermittent Pringle maneuver was considered only in case of severe bleeding. Therefore, no technological instruments, such as ultrasonic or radiofrequency dissectors, were used for the splitting procedure. The biliary anatomy was explored with a probe as described by others.19, 20 The final vessel section with the removal of the two liver grafts was done in situ after flushing of the abdominal organs with a cold solution via the aorta. In all cases, the MHV was retained with the FLG along with the inferior vena cava (IVC).

In all the cases, recipient total hepatectomy was carried out with IVC preservation and without venous-venous bypass or any temporary portacaval shunt. In the FRG transplantation, the right hepatic vein was anastomosed end to side to the recipient IVC through a caval slitting or cavoplasty to optimize the venous outflow with a 4/0 running prolene suture.21-23 In the FLG transplantation, a side-to-side caval-caval anastomosis was performed with a 4/0 running prolene suture. End-to-end portal vein anastomosis was done with a 6/0 running prolene suture with growth factor. The arterial anastomoses were performed with a 7/0 running prolene suture directly in 9 (56%) patients and with the use of vascular grafts in the remaining 7 (44%) patients as follows: 3 jump grafts to the aorta (3 FRG) and 4 extension grafts (3 FRG, 1 FLG). Thirteen (81%) patients had direct duct-to-duct biliary anastomoses according to the original surgical technique previously reported by us.24 Using a 6/0 polydioxanone surgical running suture, we performed a wide longitudinal plasty of both the donor and recipient bile ducts to produce the effect of side-to-side anastomosis. The remaining 3 (19%) patients had Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy performed with a 6/0 polydioxanone surgical running suture. In 12 (75%) patients, we placed biliary transanastomotic T-tubes.

Immune Suppression and Postoperative Care

The immune suppression was induced with rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin, cyclosporine or tacrolimus, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids. The immunosuppressive regimen was maintained only with calcineurin inhibitors since the first month after transplantation in the absence of related complications. The patients stayed in the intensive care unit for the first few days until they were recovered from a general standpoint. Then, they stayed in the surgical high-dependency unit until the discharge. Bedside color Doppler ultrasound was regularly performed to check the viability of vascular anastomoses. Postoperative trans-T-tube cholangiography was performed in patients with T-tubes 1 week after transplantation.

Control Group

From the same prospectively maintained institutional liver transplantation database, we identified 232 consecutive whole liver transplantations performed at our unit between May 1999 and December 2006 by the same surgical team: this cohort of patients was used as a control group to compare the short-term and long-term results of SLT presented here. They were 156 (68%) men and 76 (32%) women on the institutional waiting list for liver transplantations because of end-stage liver diseases.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the short-term result of SLT. For this purpose, we analyzed postoperative complications and their management. We also focused our analysis on the presence of early allograft dysfunction (EAD), a reliable and recognized indicator of the functional recovery of the graft. According to the definition made by Deschenes et al.,25 we considered EAD as the presence of at least one of the following variables between postoperative days 2 and 7 after SLT: serum total bilirubin > 10 mg/dL, prothrombin time international normalized ratio ≥ 1.6, and hepatic encephalopathy. The secondary outcome measure was the long-term result of SLT, which was mainly described by the rate of overall graft and patient survival. Finally, the tertiary outcome measure was the overall reliability of this specific transplantation, which was analyzed by a comparison of SLT with the series of whole liver transplants performed in the same period at our unit.

Continuous variables were presented as median and range. Discrete variables were presented as number and percentage. Survival time was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method from the date of transplant until death, and the statistical significance level was tested with the log rank method. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Short-Term Outcome

Early postoperative complications were recorded in 8 (50%) patients. In the FRG group, 5 (5/9, 55%) patients developed complications as follows: anastomotic biliary leakages (2), cut-edge surface biliary leakage (1), bleeding (1), and hepatic artery thrombosis (1). In the FLG group, 2 patients had hepatic vein thromboses, and 1 had cut-edge surface biliary leakage (3/7, 43%). Those patients underwent at least one resolving relaparotomy during the hospitalization. None of them was retransplanted. Table 3 shows the postoperative complications and their management.

| Graft | Complications | Management |

|---|---|---|

| FRG | Anastomotic leak (Roux) | Relaparotomy, toilette |

| FRG | Surface leak | Relaparotomy, toilette |

| FRG | Anastomotic leak (duct-to-duct anastomosis) | Relaparotomy, Roux |

| FRG | HAT | Relaparotomy, Fogarty + graft |

| FRG | Surface leak, hemorrhage | Relaparotomy, toilette |

| FLG | HVT | Relaparotomy |

| FLG | HVT, hemorrhage | Relaparotomy, toilette, new side-to-side cavocaval anastomosis |

| FLG | Hemorrhage | Relaparotomy, toilette |

- Abbreviations: FRG, full right graft; FLG, full left graft; HAT, hepatic artery thrombosis; HVT, hepatic vein thrombosis; Roux, Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy.

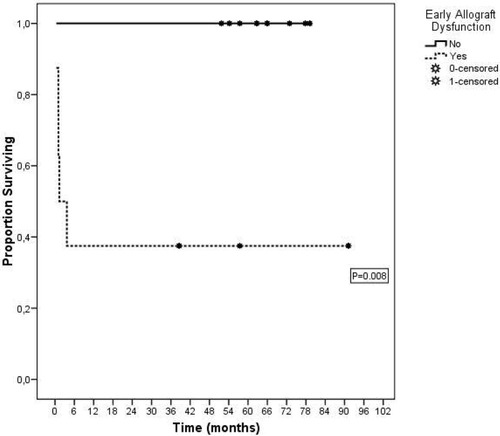

According to the previously reported definition, 8 (50%) patients developed EAD, and the survival rate was significantly poorer compared with that of patients with good functional recovery of the graft (P = 0.008). Indeed, not even one patient died in the group without EAD, and the 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rate for patients with EAD was 37.5%, all the deaths being recorded during the first 3 months after transplantation (Fig. 1).

Overall survival curves of patients and grafts after split-liver transplantation for two adult recipients calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method and stratified on the presence/absence of early allograft dysfunction.

Long-Term Outcome

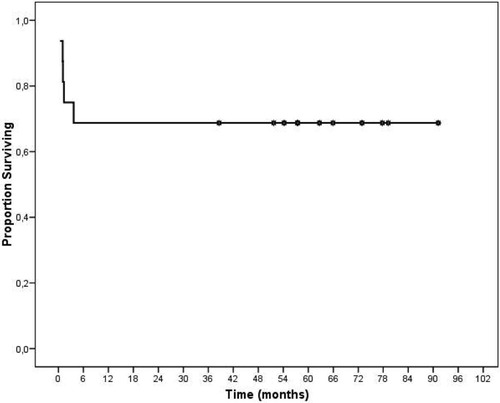

After a median follow-up of 55.82 months (mean, 44.78; range, 0.4-91.2), 5 (31%) patients died because of delayed postoperative complications. Out of those 5 patients, 3 had FRG, and 2 had FLG transplantation. They developed the following severe complications, which were fully, but unsuccessfully, treated: sepsis from biliary leakage from the Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy (1; postoperative day 110), multiorgan failure (2; postoperative days 31 and 112), hepatic artery thrombosis and sepsis (1; postoperative day 40), and hepatic vein thrombosis (1; postoperative day 32). When these patients were also considered, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rate for patients and grafts was 69% (67% for FRG and 71% for FLG). Figure 2 shows the overall survival for patients and grafts calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method.

Overall survival curve of patients and grafts after split-liver transplantation for two adult recipients calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method.

We also reviewed the outcome of the 5 contralateral liver grafts transplanted in other centers according to our program for organ sharing as previously described. Of these 5 patients, 1 died 3 months after transplantation because of septic complications in a small-for-size syndrome, whereas the remaining 4 patients were alive: 3 of them, however, experienced major morbidities in the postoperative course. We did not consider further these 5 patients in our analysis because they were transplanted in other centers, most likely with differences in indication, surgical technique, and postoperative care.

Short-Term and Long-Term Outcome of Whole Liver Transplantation as a Control Group

Among the 232 whole liver transplants performed in the same period of time, 53 (23%) developed early or delayed postoperative complications: 9 (4%) had arterial-related complications, and 30 (13%) had biliary-related complications. After a median follow-up of 57.37 months (mean, 55.11; range, 1-102.83), the 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall patient survival was 87%, 82%, and 80%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study shows the results of 16 consecutive split-liver transplants for two adults performed in a single institution with the FRG or FLG according to a well-established technique for liver resection and liver transplantation.

Full right and full left SLT was first described in 1999, but despite the initial enthusiasm, this procedure did not maintain its attractive promise.11 Indeed, approximately 100 cases of this procedure have been described worldwide with sparse and disparate results, and nowadays, SLT for two adults is still considered an experimental operation by some authors.26, 27

There are several reasons for this lack of popularity. First and foremost, the procurement of FRG and FLG for two adult recipients is a technically demanding surgical procedure that mandates surgeons very experienced in liver resection and transplantation both during the graft procurement and during the transplant. Second, there is no agreement on indications, surgical technique, and results, and therefore it is difficult to draw precise conclusions on the basis of previously published series. Third, SLT requires a very efficient system for organ sharing, which should be able to support a dedicated program for appropriate coordination between the donor and recipient teams, which are often working in different institutions. Indeed, some SLT programs have been closed after a few cases because of technical and logistical issues and because of the poor initial results.26, 28 Fourth, the theoretical feasibility of SLT for two adults has been estimated to be less than 15%. This is a very low rate that may be explained by the consideration that the finding of healthy big donors is rare at best.29, 30

On the basis of the short-term results herein reported, 50% of our patients developed complications after SLT. In our opinion, such a high morbidity rate is hard to accept and represents a major caveat for the real feasibility of SLT for two adults. In fact, only 23% of the patients who underwent whole liver transplantation in the same period developed complications. This finding might support the observation that SLT is still an experimental procedure. As a matter of fact, two main issues seem to jeopardize the feasibility of SLT for two adults: the biliary and venous outflow complications.

The previously reported studies on living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) showed a rate of biliary complications between 22% and 64%.31-35 In the series herein reported, those complications affected 4 patients (3 FRG, 1 FLG; 25%); among them, 2 had anastomotic leakages, and 2 had cut-edge surface biliary leakages. Generally, most biliary complications are expected in the case of FRG without the main bile duct because the presence of multiple sectorial or segmental bile ducts is a well-known risk factor for biliary complications, as confirmed by others in LDLT.36-40 Therefore, we strongly recommend keeping the main bile duct with FRG whenever possible. However, we also had 2 cases of cut-edge surface biliary leakages, which are most likely dependent on the hepatic surface care during the split procedure and possibly on the venous outflow congestion that may develop in the area close to the cut surface. The venous outflow is in fact the second critical point.

In this series, we experienced 2 (12.5%) cases of hepatic vein thromboses in the FLG group. In FLG transplantation, we did side-to-side caval-caval anastomosis, and probably a slight twist of the graft along the caval plane caused the hepatic vein thromboses. Similarly to LDLT, the performance of wide caval anastomosis to optimize the venous outflow is a crucial step.41, 42

Another key point of paramount importance is the adequate liver mass, which should be a guarantee in SLT. On the basis of the experience in LDLT, a graft-to-recipient weight ratio above 0.8 is considered adequate and safe.43, 44 However, the quality of the right or left lobe in LDLT is definitively higher than the quality of the same lobe harvested from a deceased donor. Therefore, we believe that a greater liver mass should be ensured, and further prospective studies are required to investigate this point.

The finding of EAD is useful for identifying patients at high risk for early death due to poor initial function. Unfortunately, the 5 patients who developed EAD and who died could not be retransplanted, mainly because of a septic state complicating the aforementioned reported major morbidities.

We did not perform preoperative imaging techniques on the donor because of the lack of logistic coordination between the donor and recipient institutions. However, we believe that such preoperative evaluation, carried out by computed tomography and intraoperative cholangiography, should be performed to have the best information on the vascular and biliary anatomy, particularly with respect to the MHV tributaries, and to calculate the liver volume.

The liver parenchymal transection can be done in situ or ex situ.45, 46 In situ splitting allowed us to have a shorter cold ischemic time, meticulous control of the graft perfusion before the final division, and minimal bleeding from the cut surface on reperfusion. However, in situ splitting is a time-consuming procedure that requires stable hemodynamic conditions and excellent coordination with other transplant teams. The liver parenchymal transection was carried out without dedicated technological instruments, and this point might be blamed for the theoretically increased risk of bleeding intraoperatively in the donor and postoperatively in the recipient. Indeed, we believe that appropriate technological instruments, such as the ultrasonic liver dissector, may offer several benefits and should be part of the harvesting armamentarium.

Regarding the long-term survival of SLT, the 3-year survival rate (69%) is comparable to that based on the European Liver Transplant Registry data on transplantation with right extended grafts, which has been reported to be 70%.4 Therefore, according to this point of view, the survival rate in our series may be considered adequate, especially for a procedure still considered experimental in some centers. In our opinion, however, a much more reliable comparison should be made with the results of whole liver transplantation, which is still the standard of care in liver transplantation. Our data on 232 consecutive whole liver transplants performed by the same surgical team show a substantial difference in terms of both short-term and long-term results. If we consider the 1-year survival rate as an outcome indicator in transplantation, the finding of 69% for SLT versus 87% for whole liver grafts is compelling evidence for poorer reliability of SLT for two adults.

Finally, we believe that SLT for two adult recipients should be carried out only in the case of absence of an urgent need for a pediatric graft because to deny such transplantation would be unethical at best. Indeed, in our country, SLT is possible only because the pediatric waiting-list mortality for liver transplantation is close to zero.47, 48

In conclusion, SLT for two adult recipients is a technically demanding procedure that requires complex logistics and surgical teams very experienced in both liver resection and transplantation but yields results debatable at best. Strong refinements in donor-recipient matching, preoperative donor evaluation, and surgical technique might be the tools to improve the outcome. The true feasibility of such transplantation remains under investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Rita De Gasperi for her valuable assistance during the manuscript preparation.