Anti-erythropoietin antibody–mediated pure red cell aplasia in a living donor liver transplant recipient treated for hepatitis C virus

Abstract

After liver transplantation, reinfection of the newly engrafted liver with hepatitis C virus is essentially universal in patients who are viremic at the time of transplantation. Treatment with interferon preparations with or without ribavirin is recommended in patients with marked histologic injury; however, hematologic toxicity associated with therapy has been reported, which is usually treated with growth factor support, including erythropoietin analogues. We present the first reported case of anti-erythropoietin antibody–mediated pure red cell aplasia arising in the setting of hepatitis C virus therapy in a patient who underwent living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpt 13: 1589–1592. 2007. © 2007 AASLD.

End-stage liver disease due to hepatitis C infection represents the most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States. Unfortunately, reinfection of the allograft with histologic injury is essentially universal in patients who are hepatitis C virus (HCV) viremic at the time of transplantation.1 At present, anti-HCV directed therapy that uses interferon (IFN) preparations with or without ribavirin is recommended in patients with marked histologic injury.2, 3 However, several investigators have noted both a decrease in efficacy of these preparations and an increase in side effects associated with therapy when comparing HCV-infected patients after transplantation to patients who did not undergo transplantation,4, 5 likely because of bone marrow suppression in the setting of multiple pharmacologic agents and renal insufficiency, which exacerbates ribavirin-induced hemolysis. In response to anemia precipitated by HCV therapy, the use of erythropoietin (EPO) analogues is recommended. In nonimmunosuppressed patients, particularly in individuals undergoing prolonged therapy, anti-EPO antibody–mediated pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) has been rarely reported.6, 7 Herein we describe what is to our knowledge the only reported case of this disease entity arising in an immunosuppressed patient after liver transplantation.

Abbreviations

HCV, hepatitis C virus; IFN, interferon; EPO, erythropoietin; PRCA, pure red cell aplasia; IFN-α, interferon alfa; cpm, counts per minute.

PATIENT AND METHODS

The patient was a 56-year-old white man who underwent living donor liver transplantation in July 2002. The patient was clinically stable on an immunosuppression regimen that consisted of cyclosporine (Neoral, Novartis, East Hanover, NJ), mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept Roche, Nutley, NJ), and prednisone. In February 2003, the regimen was changed to tacrolimus (Prograf, Astellas Pharma, Deerfield, IL). Surveillance for histologic recurrence of hepatitis C was performed via liver biopsy every 6 months. In November 2004, in response to liver biopsy results revealing recurrent hepatitis C infection with marked histologic injury (grade 2, stage 2), therapy was initiated with pegylated IFN alfa (IFN-α; Peg-Intron, Schering Plough, Kennilworth, NJ) and ribavirin, at an initial dosage of 0.5 μg/kg a week and 200 mg a day, respectively. Baseline hemoglobin was 14.0 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 91.2 fl.

Twelve weeks into therapy, the patient developed a normocytic anemia. His hemoglobin level decreased to 10.6 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 98.8 fl. Serum chemistries revealed normal iron stores. In September 2005, treatment with subcutaneous Procrit Epoetin alpha (Ortho Biotech, Inc., Bridgewater, NJ) was initiated at a dosage of 40,000 U weekly. Treatment with pegylated IFN and ribavirin continued at a dosage of 1.5 μg/kg a week and 200 mg twice a day, respectively, and the hemoglobin levels remained stable at approximately 11.0 g/dL.

In November 2005, the patient's hemoglobin decreased to 7.9 g/dL. Because the patient had completed 48 weeks of treatment with IFN and ribavirin and was aviremic, treatment was discontinued. Procrit was continued at the same dose. Despite these interventions, the patient remained anemic and was referred to a hematologist-oncologist (J.G.M.) for further evaluation in February 2006.

Hematologic evaluation revealed a normocytic anemia with the hemoglobin reaching a nadir of 4.5 g/dL. The reticulocyte count was 0.7%. Iron studies were compatible with ineffective erythropoiesis. Serologic testing for parvovirus B19 antibodies, a potential cause of PRCA in solid organ transplant recipients, was negative. Bone marrow evaluation showed a normocellular bone marrow with maturing hematopoietic cells with mild to moderate erythroid hypoplasia and no maturation arrest or infiltrative disorder. Stains for acid-fast bacilli were negative. Flow cytometry and karyotype analyses were normal.

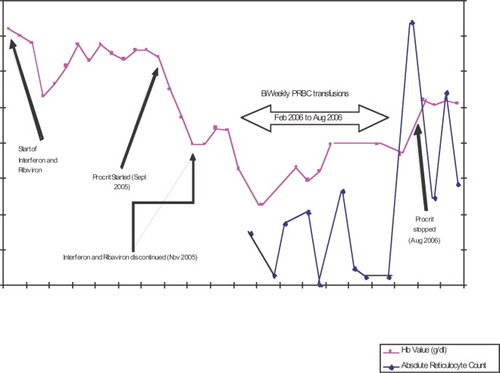

The patient required 2 U of packed red cell transfusions on a biweekly basis to maintain hemoglobin values of approximately 7.0 g/dL (Fig. 1). Subcutaneous Procrit was continued at 40,000 U per week. Eight months after withdrawal of pegylated IFN and ribavirin, a second bone marrow biopsy and aspirate was performed. This evaluation revealed a hypocellular marrow with nearly absent erythroid precursors, suggesting a diagnosis of pure red cell aplasia. Megakaryocytes and cells of the myeloid lineage were normal in number and morphology. In situ hybridization performed to detect Epstein-Barr virus was negative. Flow cytometry, karyotype, and fluorescent in situ hybridization tests for known chromosomal abnormalities that accompany myelodysplastic syndromes were normal. The diagnosis of EPO antibody–mediated PRCA was considered, and Procrit was discontinued. Serum collected from the patient was sent for analysis. Twelve weeks after Procrit was withdrawn, the anemia improved, and the patient no longer required red cell transfusion support.

Hemoglobin trend.

RESULTS

Serum collected in August 2006 was sent to PPD CLIA Immunochemistry Laboratory in Richmond, Virginia, and EPO level and antibody concentration were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and radioimmunoprecipitation assay, respectively. At a 1:20 dilution, the patient's serum EPO antibody concentration was positive at 9.8% counts per minute (cpm; radioimmunoprecipitation assay: negative/normal, ≤0.6; borderline, >0.6-<0.9; positive ≥0.9% cpm). Serum collected from the patient had an EPO level of 82.9 mU/mL (reference range, 10-30 mU/mL). This value was considered to be high because of the patient's endogenous EPO production because Procrit had been discontinued in July 2006, approximately 1 month before specimen collection.

A second serum specimen was collected in October 2006, approximately 6 weeks after the first serum specimen collection. The analysis revealed an EPO level of 54.6 mU/mL and an EPO antibody titer of 17.6% cpm (1:20 dilution). A confirmatory assay for EPO-neutralizing antibodies (Johnson & Johnson, Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Raritan, NJ) was performed and was positive as determined by 3H thymidine UT-7/EPO cell proliferation assay, as described by Kelley et al.8

DISCUSSION

Recurrence of hepatitis C infection with histologic injury is essentially universal after liver transplantation in patients who are viremic at the time of transplantation. In the setting of histologic recurrence, therapy with IFN and ribavirin is recommended; however, response rates are decreased and the incidence of hematologic side effects is increased in the posttransplantation setting when compared with nontransplanted patients.4, 5 When hematologic side effects associated with IFN and ribavirin therapy are encountered, growth factor support is recommended; however, anti-EPO antibody–PRCA can be a rare side effect of the use of recombinant EPO products used to treat anemia. Herein, we describe what is to our knowledge the first reported case of anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA in a transplant recipient.

Our patient underwent living donor liver transplantation and developed histologic recurrence of hepatitis C. During therapy with pegylated IFN and ribavirin, the patient developed refractory anemia, which persisted despite the use of growth factor support. After an extensive evaluation to explore alternative causes of anemia, we concluded that the patient developed anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA.

PRCA is a red cell disorder characterized by absent red cell precursors in the bone marrow, anemia, and reticulocytopenia. This disorder may be congenital (Diamond-Blackfan syndrome) or induced by medication, viral infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disorders.6 With the advent of recombinant human EPO therapy in the late 1980s, anti-EPO antibody–associated PRCA has emerged as a clinical entity. To date, >200 cases of this disorder have been described.7 Diagnostic criteria for the syndrome include use of EPO for ≥3 weeks, a drop in hemoglobin level approximating 1 g/L a day in the absence of transfusion, reticulocyte count of <10 × 109/L, and no clinically significant decrease in white cell or platelet counts.9 The diagnosis, as in our patient, is typically confirmed by a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy, which demonstrate maturation arrest of red cell precursors and a serum assay showing presence of EPO antibody with neutralizing ability. Because of formulation issues presumed to increase immunogenicity, most anti-EPO antibody–associated PRCA has been attributed to the rHuEPO products available in Europe, including the following: Eprex (epoetin alpha; manufactured by Ortho Biologics and distributed and marketed as Eprex or Erypo by Ortho Biotech, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and Janssen-Cilag, Issey-les-Moulineaux, France), Aranesp (darbepoetin alpha, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), and NeoRecormon (epoetin beta, Roche, Basel, Switzerland).10, 11

Two confirmed cases of anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA arising from use of Procrit (epoetin alpha, manufactured by Amgen and distributed and marketed by Ortho Biotech Products, Bridgewater, NJ) have been described in the United States.12, 13 The first case occurred in a 66-year-old woman with polycystic kidney disease who developed PRCA after treatment with Procrit for refractory anemia. The second case involved a 50-year-old man who was treated with Procrit after he developed anemia secondary to IFN-α and ribavirin therapy for hepatitis C infection. In both cases, EPO antibodies were detected by bioassay. In contradistinction, there have been other case reports of anemia presumably due to PRCA developing in patients treated with ribavirin in combination with IFN,14 and ribavirin in combination with mycophenolate mofetil.15 In addition, IFN-α monotherapy as therapy for hepatitis C has been implicated in a case of PRCA16 and in 2 cases when combined with hydroxyurea to treat hematologic malignancies.17, 18 However, in these cases, no documentation of the presence of EPO antibodies was found.

Previously published case reports in which 2 of 3 patients developed anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA from exposure to Procrit reveals that these patients were also receiving IFN-α and ribavirin for the treatment of hepatitis C. We hypothesize that the immunomodulating effects of IFN-α, including its ability to promote autoimmunity,19, 20 are permissive in the development of EPO antibody–mediated PRCA after exposure to Procrit. The incidence of Procrit related anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA is decreased when compared with Eprex, an EPO product with a different degree of glycosylation thought to be more immunogenic.21 Thus, the clinical development of anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA after exposure to EPO analogues may be due to immune dysregulation.

It is noteworthy that the patient we describe in this report developed anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA despite an immunosuppression regimen that would presumably minimize antibody production. This phenomenon is even more striking when coupled with the observation that although there are no standard guidelines for the treatment of anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA, immunosuppressive medications are often the mainstay of therapy.22 Retrospective data from European centers have documented varying levels of clinical recovery in patients with PRCA treated with combinations of corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporin, rituximab, or mycophenolate mofetil.23 As an interesting contrast to our case, IFN has been used successfully in the treatment of idiopathic pure red cell aplasia.24

In conclusion, we report a patient with anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA who developed this phenomenon despite immunosuppression after living donor liver transplantation. This is a rare but distinct clinical complication of recombinant EPO therapy and should be considered in the evaluation of any patient with worsening anemia despite the use of EPO products, particularly if the patient is known to have altered immune function. As in our patient, prompt recognition of anti-EPO antibody–mediated PRCA and withdrawal of EPO can be associated with clinical recovery. Further exploration of the concept of immunostimulation as a mechanism to induce this phenomenon is warranted.