Histologic findings in recurrent HBV

Abstract

Key Concepts:

- 1

The histopathologic presentation of hepatitis B (HB) infection in liver allografts is generally similar to that seen in the nonallografts.

- 2

An atypical pattern of recurrent HB, i.e., fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis (FCH) occurs in a small number of patients. These patients present with a severe cholestatic syndrome, which may clinically resemble acute or chronic rejection.

- 3

There are several other possible causes of acute and chronic hepatitis in liver allografts that may need to be considered.

- 4

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the liver allograft can easily be confirmed by performing immunohistochemical stains for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). The expression pattern of these HBV antigens varies and is sometimes helpful in determining whether the liver injury is mainly from the HBV or from other causes in coexistence with the HBV infection.

- 5

Histological grading of the necroinflammatory activity and staging of the fibrosis should only be applied when the changes are related to the recurrent HB.

- 6

The pathology of liver transplantation is complex; therefore, clinical correlations remain extremely important in arriving at the final and correct diagnosis. Liver Transpl 12:S50–S53, 2006. © 2006 AASLD.

Chronic hepatitis B infection of the allografts is largely restricted to patients whose original liver disease was caused by hepatitis B. In general, without preventive measures the vast majority of patients who have HBV replication before transplantation will reinfect their allograft. Both preventive and therapeutic measures have allowed us to keep the impact of viral recurrence at an acceptable level1-3 Reinfection and recurrent hepatitis B are less predictable in patients who were transplanted for acute fulminant liver failure, or when there was coinfection with other hepatotropic viruses. This was observed best with hepatitis D virus (HDV), but was also seen with hepatitis C virus coinfection.4, 5 Coinfection with HDV or hepatitis C virus typically reduces HBV replication, which in turn diminishes the risk of HBV recurrence. As a matter of fact, the number of HDV-infected patients who had active HBV replication before transplantation was small.6 Fulminant recurrent hepatitis B and hepatitis D, however, have been reported in patients with HDV infection and active HBV replication, as they were hepatitis B e antigen– and HBV deoxyribonucleic acid–positive.7 The histopathologic features of recurrent hepatitis B or HBV/HDV are virtually similar to those seen in nonallograft livers. All forms of hepatitis, i.e., acute and chronic hepatitis of varying severity, have been described.8-10 The liver biopsy interpretation, however, may not be easy due to a number of posttransplantation complications that can occur singly or in combination with the recurrent hepatitis, and several pathologic diagnoses may need to be rendered on a single needle biopsy specimen. As a matter of fact, the detection of HBV antigens in the allograft does not always equate to HB disease.

ACUTE HEPATITIS

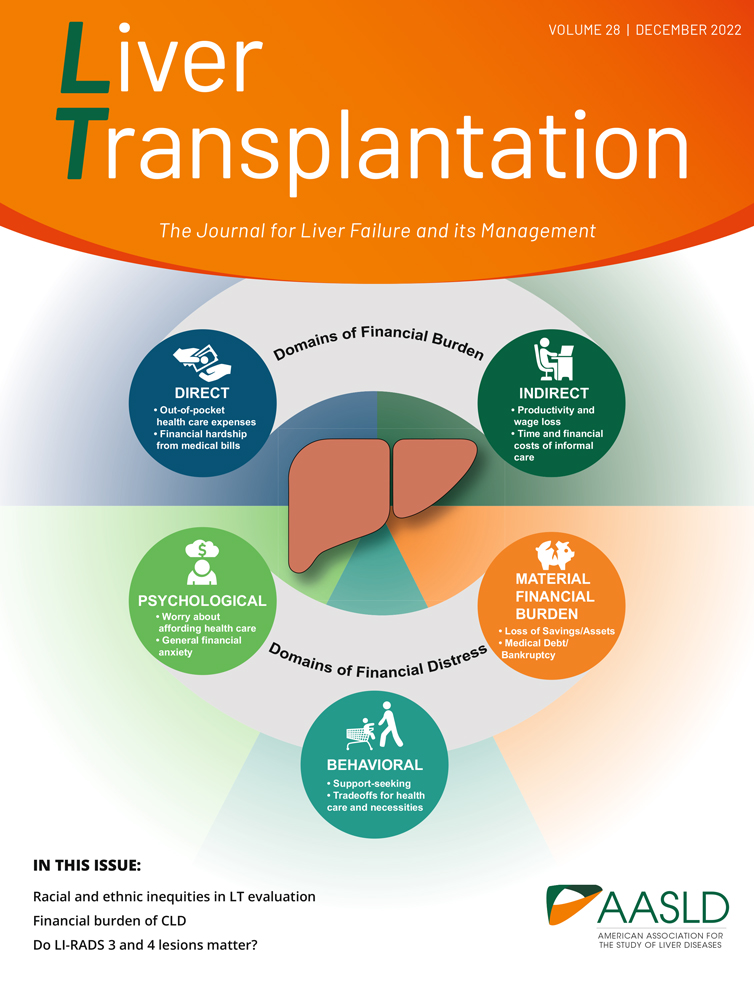

Acute hepatitis B in the allograft has a variety of presentations, ranging from asymptomatic rise of serum aminotransferase activities to gastrointestinal and influenza-like symptoms with or without jaundice. In most patients with HBV reinfection, cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of HBcAg in rare hepatocytes can be demonstrated by immunostaining 2 to 5 weeks after transplantation.9 In HDV/HBV coinfection, hepatitis D antigen is demonstrable in the nuclei of infected hepatocytes by immunostain. A mild lobular hepatitis follows at 8 to 10 weeks and usually corresponds to the first graft dysfunction that can be attributed to recurrent HBV infection. Acute hepatitis predominantly affects the hepatic parenchyma, resulting in diffuse necroinflammatory changes, Kupffer cell hypertrophy, and lobular disarray. Individual hepatocytes undergoing eosinophilic or ballooning degeneration are scattered throughout the lobules (spotty necrosis) (Fig. 1). Portal inflammation is seen to varying degrees. The inflammatory response may be somewhat reduced, presumably due to the immunosuppression. Changes milder than seen in “classic” acute hepatitis are often encountered, because posttransplantation patients are closely monitored, particularly early after transplant, thus liver biopsy is performed more readily in these patients. Stainable HBsAg follows, but ground glass hepatocytes are usually difficult to find in the acute phase.11 A more severe hepatitis with bridging necrosis and submassive necrosis may occur in a small percentage of patients. An autonomous or “isolated” HDV infection following liver transplantation with no evidence of HBV infection has been reported.12 Further studies, however, did not support this idea of HDV persistence for several weeks after transplant without the helper function of HBV infection.13

Recurrent acute hepatitis B with diffuse necroinflammatory changes in the lobules. There are scattered acidophilic bodies (arrows) and foci of parenchymal necroses (arrowheads) (hematoxylin and eosin, 100×).

Abbreviations

HB, hepatitis B; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAg, hepatitis B core antigen; HDV; hepatitis D virus; FCH, fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis.

CHRONIC HEPATITIS

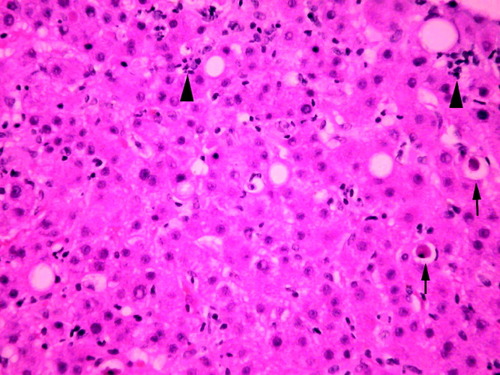

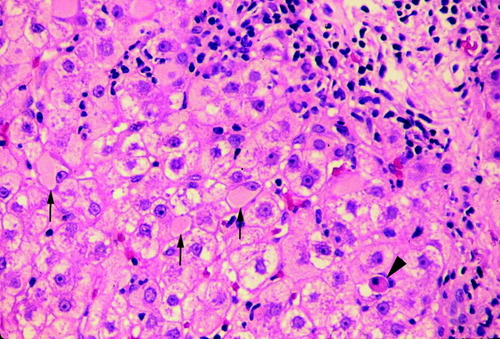

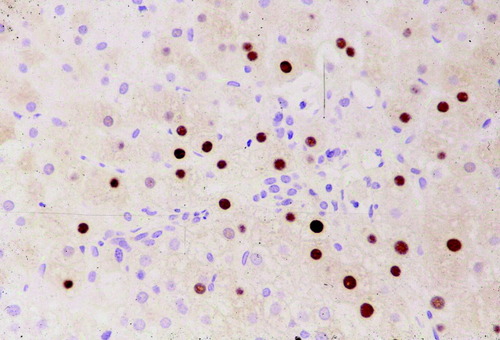

In patients with active viral replication, the disease may progress to chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. Patients with HB may be without symptoms or may complain of fatigue or other nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms. The spectrum of histopathologic findings of HB in liver allografts is similar to that in a nontransplant setting, except for a more rapid progression of the fibrosis, a more severe activity with bridging and confluent necrosis, and FCH leading to early graft failure in a small group of patients.10, 14, 15 The more aggressive course of HBV infection after transplant probably results from enhanced viral replication and attenuated host response in these patients. Chronic HB is characterized by portal fibrosis and inflammation, with or without fibrous septa, and various degrees of lobular and periportal necroinflammatory activity (interface hepatitis) (Fig. 2). The inflammatory cells are composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells. There is a reverse correlation between the number of ground glass hepatocytes and the necroinflammatory activity (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemical studies for HBsAg and HBcAg should always be performed in these cases. As in other immunocompromised hosts, HBcAg is detectable in the cytoplasm and nucleus of a large number of hepatocytes (“HBcAg predominance type”) (Fig. 4). A complete absence of stainable HBcAg in a biopsy should make us consider other causes of the allograft dysfunction besides HBV, or dual infections with hepatitis C virus or HDV.16, 17 Recurrent HDV infection could be confirmed by immunostaining of the liver for HDV antigen, the presence of HDV ribonucleic acid by molecular techniques or the presence of immunoglobulin M anti-HDV.18

Chronic hepatitis in a patient with recurrent HBV infection. There is fibrous septum with interface hepatitis, scattered ground glass hepatocytes (arrows), and acidophilic body (arrowhead) (hematoxylin and eosin, 100×).

A sheet of ground glass hepatocytes on hematoxylin and eosin (A; 200×), immunostained for HBsAg (B; 100×) and on Victoria blue stain (C; 200×).

Large number of HBcAg-containing nuclei in a typically “HBcAg predominance type” in immunosuppressed patients (Immunostain, 100×).

FIBROSING CHOLESTATIC HEPATITIS (FCH)

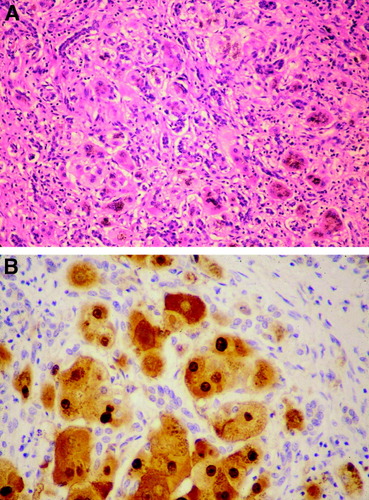

FCH is an atypical pattern of liver injury associated with HBV infection in immunosuppressed patients.19 FCH has also been reported in renal transplant recipients. It is a rapidly progressive disease with severe parenchymal damage, extensive fibrosis, and mild inflammatory reaction. The parenchymal changes include marked hepatocyte swelling and cholestasis with marked ductular reaction. Cases of FCH often progress to portal and periportal sinusoidal fibrosis and lobular collapse (Fig. 5). The extremely high levels of viral replication and the massive HBcAg and HBsAg expression in the liver, in addition to the nonsignificant inflammatory component suggest a direct cytopathic effect of HBV.20 Other atypical forms of recurrent hepatitis B associated with heavy viral burden have also been described: fibrosing cytolytic hepatitis,21 fibroviral hepatitis B, and steatoviral hepatitis B.22 FCH has not been reported in HDV/HBV coinfected patients.23

FCH with marked ductular reaction (A; hematoxylin and eosin, 100×) and high level of HBcAg expression in nuclei and cytoplasm of hepatocytes (B; Immunostain, 200×).

IMMUNOPATHOGENESIS

In nonimmunocompromised patients, HBV is considered to be noncytopathic, and elimination of HBV-infected hepatocytes at the cost of hepatocyte injury is mediated by cytotoxic T cells. Marinos et al.24 suggested that the same mechanism apply in liver allograft, in that cytotoxic T cells recognize HBV determinants, most importantly HBcAg,25 expressed in association with human leukocyte antigen class 1 on the surface of hepatocytes. In acute hepatitis B, an immune-mediated cytolytic response aids in resolution of viral infection. In orthotopic liver transplantation recipients, the human leukocyte antigen class 1 mismatch between the graft and the host is typical. This may contribute to the uncontrolled viral replication, and suggests an alternative mechanism independent of human leukocyte antigen class 1 restriction leading to cytokine (interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-7α) release in the hepatocyte injury.24

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES

Nonhepatotropic viruses, hepatitis C virus, drug-induced, and immune-mediated hepatitis are among the differential diagnoses of recurrent hepatitis B. The clinical differentiation between recurrent hepatitis B and acute or chronic rejection may also be difficult.26