Feasibility of using the cystic duct for biliary reconstruction in right-lobe living donor liver transplantation

Abstract

Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction has been introduced in adult living donor liver transplantation (LDLT). In right-lobe grafts, however, the presence of two or three separated bile duct orifices is not rare and makes an alternative approach for reconstruction necessary. We used the cystic duct for one of the anastomoses in biliary reconstruction for 5 right-lobe living donor liver transplants with two separated ducts. Before the anastomosis, the inside lumen of the cystic duct was straightened with a metal probe. Two external drainage tubes were placed in all recipients, and posttransplant cholangiography through the tubes approximately one month after transplantation showed no leakage or stricture at any of the anastomotic sites. The drainage tubes were removed between 17 and 37 weeks after transplantation. All of the patients except one who died of chronic rejection have been doing well without any late biliary complications during follow-up periods ranging from 10 to 28 months after transplantation. In conclusion, our results indicate that biliary reconstruction using the cystic duct is feasible and safe for living donor liver transplantation and that external drainage tubes may be effective for prevention of complications. (Liver Transpl 2005;11:1431–1434.)

Biliary tract complications are some of the most frequent problems after living donor liver transplantation (LDLT).1 In an effort to prevent the serious complications that can occur in hepaticojejunostomy, duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction, especially in right-lobe LDLT, has recently become widely accepted.2-5 The biliary tree of right-lobe grafts, however, features many anatomical variations, with absence of the right hepatic duct reported in as many as 26% of 110 resected livers.6 In many instances, two or three bile-duct reconstructions may therefore be necessary, and modified techniques for these situations have been employed.7 In situations where the distance between orifices permits it, two orifices have been transformed into one. In other cases, the right and left hepatic ducts have been used for separate anastomoses. Furthermore, if the two orifices are far apart, combining a hepaticojejunostomy with a duct-to-duct anastomosis has been attempted.2 In these special cases, a modified technique using the cystic duct for the reconstruction of one of the separated orifices of the bile duct is needed. Sue et al. reported successful use of the cystic duct for biliary reconstruction in three cases.8 However, only two of the three cases underwent a double-biliary anastomosis, and the follow-up periods were relatively short. In the study presented here, we review 5 LDLT transplants performed with a double-biliary reconstruction technique that uses the cystic duct and the right hepatic duct for two separate anastomoses as well as two external biliary stent tubes. The efficacy of biliary reconstruction using the cystic duct with an external drainage tube was assessed during both short- and long-term follow-up periods after LDLT.

Abbreviation

LDLT, living donor liver transplantation.

Patients and Methods

Between September 2000 and December 2004, 80 cases of living donor liver transplantation were performed at our institution. Left-lobe grafts were used in 45 cases and right lobes in 30. The remaining 5 cases underwent domino transplantation with whole-liver grafts. Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction was performed for all of the right-lobe graft cases, 15 of whom had one hepatic duct, 15 had two, and none had triple orifices. At the back table, 8 double orifices were transformed into single ones. The other 7 cases needed two separate reconstructions, and for two of them the right and left hepatic branches of the recipient's hepatic duct could be used. The two orifices of the anterior and posterior branches of the graft bile duct were too far apart in the remaining 5 cases; however, the recipient's cystic duct was used for reconstruction of one of the orifices (Fig. 1).

Modalities of duct-to-duct reconstructions for right-lobe grafts.

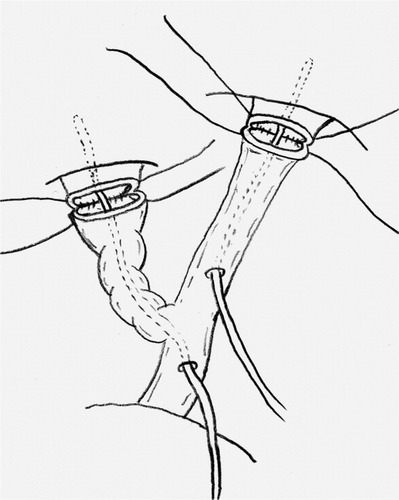

The right and left hepatic ducts were dissected at the hepatic hilum during the recipient operation and cut separately to preserve the two small orifices of the bile duct. If the information obtained from the preoperative biliary computed tomography (CT) scan or intraoperative cholangiography suggested the presence of two separate orifices of the graft bile duct, the cystic duct including the neck of the gall bladder was preserved as long as possible during the recipient operation. The stump of the cystic duct was tapered down to the size of the graft bile duct before reconstruction. We usually confirmed the arterial blood supply at the stump of the cystic duct by cutting the wall of the edge. Before the anastomosis, the spiral form of the inside lumen of the cystic duct was straightened by gently prodding it with a metal probe until it was dilated and entirely passable. Reconstruction was performed in an end-to-end fashion between the graft bile duct and the recipient hepatic duct or cystic duct with interrupted 6-0 PDS suture. Two 4-French polyethylene tubes, inserted via the left hepatic duct in one, via the cystic duct in one, and via the common bile duct in the other cases, were used for external drainage (Fig. 2). Cholangiography through both tubes was performed approximately one month after transplantation. Biliary complications were diagnosed clinically, biochemically, or radiologically.

Schema of separated anastomosis of two bile ducts using the cystic duct and the placement of two external drainage tubes.

Results

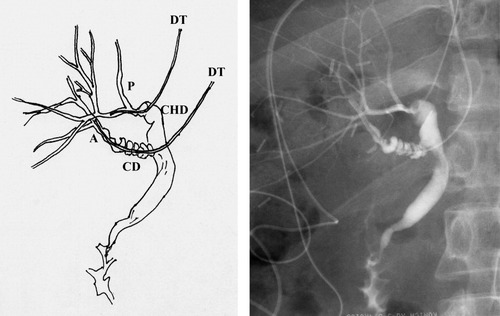

Patients' demographics are shown in Table 1. There were 5 males and one female with an age range from 18 to 58 years. The underlying diseases were hepatitis C with hepatocellular carcinoma in two patients, and hepatitis B, Caroli disease, and fulminant hepatic failure in one each. The distance between the orifice of the anterior branch and the posterior branch in the right-lobe grafts of all the patients was more than 1.5 cm. The cystic duct was anastomosed to the anterior branch in three and to the posterior branch in two. The right hepatic duct was used for all other reconstructions. There were no clinical signs of leakage during the early postoperative periods, and cholangiography performed around one month after transplantation did not show either leakage or stricture of the anastomotic sites (Fig. 3). The external biliary drainage tubes were removed between 17 and 37 weeks after transplantation. Patient 1 died of chronic rejection 13 months after transplantation without any signs of biliary complications throughout the entire postoperative course. Although patients 2 and 3 suffered from recurrence of hepatitis C as evidenced by abnormal biochemical findings, they recovered with the aid of interferon and ribavirin therapy. Patient 5 exhibited hyperbilirubinemia due to rejection but recovered after administration of silorimus. Follow-up periods ranged from 11 to 28 months (median 14 months). All patients but one are alive and doing well without any clinical signs of biliary complications more than 10 months after transplantation.

| Patient | Age/Gender | Disease | Mode of Biliary Reconstruction | Follow-up Periods | Results (Biliary Complication) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39/M | HBV | Ant-CD, Post-RHD | 13 months | Dead* (none) |

| 2 | 53/M | HCV/HCC | Ant-RHD, Post-CD | 28 months | Alive (none) |

| 3 | 58/M | HCV/HCC | Ant-CD, Post-RHD | 14 months | Alive (none) |

| 4 | 18/M | Caroli disease | Ant-RHD, Post-CD | 13 months | Alive (none) |

| 5 | 44/F | FHF | Ant-CD, Post-RHD | 10 months | Alive (none) |

- Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B; HCV, hepatitis C; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; FHF, fulminant hepatic failure; Ant, anterior branch of the right hepatic duct of the graft; Post, posterior branch of the right hepatic duct of the graft; CD, cystic duct of the recipient; RHD, right hepatic duct of the recipient.

- * Patient 1 died of chronic rejection.

Cholangiography through the external drainage tubes one month after liver transplantation in patient 1. Neither leakage nor stricture was detected. CD, cystic duct; CHD, common hepatic duct; A, anterior branch of right hepatic duct of the graft; P, posterior branch of right hepatic duct of the graft; DT, external drainage tube.

Discussion

During the early stages of LDLT development, the biliary system usually was reconstructed by means of a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Later, duct-to-duct reconstruction was introduced, especially for adult LDLT, because of its advantages over hepaticojejunostomy, such as shorter operation time and simpler biliary reconstruction. Furthermore, in the event of leakage at the anastomotic site, serious complications in duct-to-duct reconstructions are rare in contrast to hepaticojejunostomy, where division of the Roux-en-Y limb may be necessary. Therefore, duct-to-duct reconstruction for adult LDLT has been widely accepted in conjunction with the increase in right-lobe LDLT. However, because there are many variations in bile-duct branches, especially in the case of right-lobe grafts, some modifications are needed for multiple bile-duct reconstructions. Sometimes hepaticojejunostomy combined with duct-to duct reconstruction should be considered for reconstruction of two bile ducts that are too far apart. One of the solutions for this particular problem is to use the cystic duct for one biliary anastomosis. Although use of the cystic duct for duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction has been previously reported, there are few descriptions of this technique as an alternative to a two-bile-duct reconstruction, and none of them report long-term outcomes.3, 9

Cholangiography performed through the external drainage tubes about one month after transplantation showed no leakage or stricture at the anastomotic site in any of our 5 recipients. During dissection of the bile duct and cystic duct for the recipient operation, we paid attention to preserving the connective tissue around the wall as much as possible to keep the blood supply and tried to ensure the patency of the cystic duct by dilating the spiral lumen before anastomosis. Although Liu et al. reported excellent results for duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction of right-lobe LDLT without biliary drainage10 and also reported that the biliary stenting was one of the risk factors for biliary complications,11 we still consider the use of small external drainage tubes preferable because of several advantages. First, it allows us to obtain information about bile juice production and hence about the graft function. Second, biliary drainage can be used to reduce pressure at the anasomotic site to prevent leakage. And finally, the external drainage tubes can help to keep the lumen open, which may be important particularly when dealing with a spiral cystic duct. A recent study described complete obstruction of the anastomosis of a cystic duct and a donor right anterior hepatic duct one month after transplantation because of fibrous tissue replacing the anastomotic site.12 The technique described here, including the use of drainage tubes, could avoid early obstruction. In addition, cholangiography can be performed through the tubes to determine whether any leakage or stricture has occurred. However, this technique also has some disadvantages, such as a waiting period of several months before the tubes can be removed because of the possibility of bile leakage from the insertion site in the wall of the bile duct. This is especially problematic when the tubes need to be kept in place for long periods of time, such as in the case of recipients who show continuous ascites after transplantation. Moreover, immediately after we removed the drainage tubes three months posttransplantation, fever, abdominal pain, and signs of infection developed in some recipients and required administration of antibiotics.

These disadvantages are in addition to the fact that biliary strictures occur in 15 to 33% of patients who undergo LDLT with duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction, whereas such strictures do not occur as frequently in hepaticojejunostomy.2, 9, 10, 13 However, endoscopic access is easier in duct-to-duct reconstruction for either examination or treatment of biliary strictures. Hisatsue et al. reported that 13 of 14 patients who showed biliary stricture after duct-to-duct reconstruction were successfully treated with an internal stent.14 It could therefore be argued that even though a cystic duct anastomosis has its problems, they are outweighed by the possibility of endoscopic access after transplantation.

In conclusion, using the cystic duct for separated biliary duct reconstruction is a feasible and safe technique as demonstrated by short-term as well as long-term results after LDLT. In addition, external drainage tubes may be effective for preventing leakage or stricture of the cystic duct anastomosis.