Pedicle clamping with ischemic preconditioning in liver resection

Abstract

Hepatic pedicle clamping (HPC) is widely used to control intraoperative bleeding during hepatectomy; intermittent HPC is better tolerated but is associated with blood loss during each period of reperfusion. Recently, it has been shown that ischemic preconditioning (IP) reduces the ischemia-reperfusion damage for up to 30 minutes of continuous clamping in healthy liver. We evaluated the safety of IP for more prolonged periods of continuous clamping in 42 consecutive patients with healthy liver submitted to hepatectomy. IP was used in 21 patients (group A); mean ± SD of liver ischemia was 54 ± 19 minutes (range, 27-110; in 7 cases >60 minutes). In the other 21 patients, continuous clamping alone was used (Group B); liver ischemia lasted 36 ± 14minutes (range, 13-70; in 2 cases >60 minutes). Two patients in Group A (9.5%) and 3 in Group B (14.2%) received blood transfusions. In spite of the longer duration of ischemia (P = .001), patients with IP had lower aspartate aminotransferase (AST; P = .03) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT; P = not significant) at postoperative day 1, with a similar trend at postoperative day 3. This was reconfirmed by multiple regression analysis, which showed that although postoperative transaminases increased with increasing duration of ischemia and of the operation in both groups, the increases were significantly smaller (P < .001) with the use of preconditioning. In conclusion, the present study confirms that IP is safe and effective for liver resection in healthy liver and is also better tolerated than continuous clamping alone for prolonged periods of ischemia. This technique should be preferred to continuous clamping alone in healthy liver. Additional studies are needed to assess the role of IP in cirrhotic liver and to compare IP with intermittent clamping. (Liver Transpl 2004;10:S53–S57.)

Reduction of blood loss and limitation of blood transfusions during liver resection are considered main goals of liver surgery. In fact, the amount of blood transfusion during hepatectomy has a significant impact on morbidity and mortality.1-6 However, low mortality, already achieved by expert surgical teams, can no longer be considered the only criterion for evaluating the results of this surgery. Thus, the capacity to limit the number of transfused patients and the quantity of blood units transfused per patient has become a measure of high-quality liver surgey. Prospective studies and the experiences reported by dedicated centers have demonstrated that vascular clamping techniques, in particular hepatic pedicle clamping (HPC), are effective and safe in limiting bleeding during parenchymal transection.7-11

Recently, a new method of occlusion of inflow to the liver has been proposed by Clavien et al.,12 based on a short period of ischemia of the liver (preconditioning), followed by a short period of reperfusion and subsequent prolonged continuous clamping. Clavien et al. showed that ischemic preconditioning (IP) in noncirrhotic liver, for up to 30 minutes of continuous clamping, increased tolerance to ischemia-reperfusion when compared to continuous clamping alone.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of this preconditioning technique for more prolonged periods of continuous clamping.

Abbreviations

HPC, hepatic pedicle clamping; IP, ischemic preconditioning; DOS, duration of surgery; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Patients and Methods

From January 2001 to December 2002, 42 consecutive patients submitted to major and minor anatomical resections were studied. Patients with liver cirrhosis or jaundice were excluded. Patients were randomized into 2 groups, A and B. Characteristics of the 2 groups of patients are shown in Table 1. In group A, liver resections were performed with continuous clamping after IP. IP consisted of 10 minutes of portal triad clamping followed by 10 minutes of reperfusion-continuous clamping up to the end of resection.

| Preconditioning (Group A) | Continuous Clamping (Group B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 21 | 21 | |

| Age (yr) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 50 ± 14 | p = ns | 57 ± 11 |

| (range) | (22-74) | p = ns | (34-72) |

| Gender (M/F) | 12/9 | p = ns | 11/10 |

| Indications for resection | |||

| Benign disease | 5 | p = ns | 7 |

| Malignant disease | 16 | p = ns | 14 |

| Type of resection* | |||

| Major resections | 6 | p = ns | 8 |

| Right hepatectomy | 4 | 4 | |

| Left hepatectomy | 2 | 3 | |

| Trisegmentectomy | — | 1 | |

| Minor resections | 15 | p = ns | 13 |

| Bisegmentectomy | 8 | 4 | |

| Segmentectomy | 7 | 9 |

- * (according to Couinaud classification)

In group B, liver resections were performed using continuous clamping without preconditioning.

The 2 groups of patients were matched by age, sex, indication for liver resection (malignant/benign disease), and type of resection (major/minor resection according to Couinaud classification).

Surgical Technique

In all patients, bilateral subcostal incision, with a midline incision up to the xiphoid, was used. Intraoperative ultrasound was performed before deciding on the type of resection. In cases of major resection, control of vascular inflow and outflow was obtained beforehand. Hepatic veins were divided with a vascular linear stapler or were ligated by means of 4-0 nonabsorbable running suture. The biliary duct was divided at the end of parenchymal transection. Clamping of the hepatic pedicle was performed with a vascular tourniquet or vascular clamp, which was also used to clamp the accessory left artery when present.

When preconditioning was used, transection of the liver was started immediately after initial clamping and interrupted after the first 10 minutes of preconditioning; a period of reperfusion of 10 minutes was then allowed, during which the parenchymal transection was interrupted. Continuous clamping was subsequently carried out and prolonged until the resection was completed.

Transection of the liver was performed using the Kelly clamp “crushing” technique and bipolar forceps; hemostasis and biliostasis were obtained by absorbable thin (4-0) sutures and absorbable clips (Absolok Extra AP200 and AP300, Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH). In all patients, central venous pressure (CVP) was monitored by a central venous catheter and arterial pressure by a radial catheter. During parenchymal transection, CVP was maintained below 4 cm H2O.

Duration of surgery (DOS) in group A was 321 ± 92 minutes (mean ± SD), and DOS in group B was 339 ± 112 minutes. Duration of liver ischemia in group A (IP) was 54 ±19 minutes (range, 27-110); in 7 cases (33 %), it was prolonged for more than 60 minutes. In group B (continuous clamping alone), duration of liver ischemia was 36 ± 14 minutes (range,13-70 minutes), and in 2 cases (9.5 %) it was prolonged for more than 60 minutes. Duration of ischemia in patients with IP was significantly longer than in those with continuous clamping alone (P = .001).

Intraoperative transfusions were performed for hemoglobin level <9 g/dL and hematocrit <28%; however, in patients over 70 or in those with ischemic cardiac disease, transfusions were perfomed for hemoglobin level <10g/dL and hematocrit <30%.

With the aim of comparing the 2 groups, the following factors were evaluated: perioperative mortality and morbidity rates, number of patients who required blood transfusions during or after surgery, duration of surgical procedures, and postoperative serum profiles of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin, prothrombin activity, and total cholesterol.

Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as mean ±SD. Comparisons were carried out using Student's t test and least square regression analysis: a P value below .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Operative and postoperative mortality were zero. Postoperative complications were observed in 3 patients (7.1%), 2 of whom belonged to group A (9.5 %). The first complication observed was the development of postoperative pneumonia in a 74-year-old woman who underwent right hepatectomy and simultaneous closure of a temporary colostomy and repair of an incisional hernia with an intraperitoneal-expanded polytetrafluoroethylene prosthesis. Wound infection was observed in the second patient, a 52-year-old woman who had undergone right hepatectomy for recurrent cholangitis from benign stenosis of the right hepatic duct. The third patient with a complication belonged to group B (4.7%). This patient was a 60-year-old man who underwent right hepatectomy for hemangioma and subsequently developed a subphrenic abscess. There were no specific complications related to the HPC.

Five patients received intraoperative blood transfusions (11.9%). Two patients in group A received 3 and 5 blood units, respectively. Three patients in group B received 1 blood unit each. Four of these patients had undergone a major resection. In addition, 2 other patients in each group received 1 autologous blood unit each, with no need for postoperative transfusions.

Postoperative blood chemistry showed that, in spite of the significantly longer mean duration of ischemia (54 vs. 36 minutes), patients with preconditioning (compared to those without) had lower values of AST (P = .03) and ALT (P = not significant) at postoperative day 1 (Fig. 1). There was a similar trend for transaminases at postoperative day 3, without evident or significant differences in other variables (Fig. 2).

Postoperative changes in (A) AST and (B) ALT at postoperative day 1, 3, and 7 after liver resection with continuous clamping (- ⊖ -) alone or with preconditioning (

).

).

Postoperative changes in total cholesterol (a), total bilirubin (b), and prothrombin (c) activity at postoperative day 1, 3, and 7 after liver resection with continuous clamping (- ⊖ -) alone or with preconditioning (

).

).

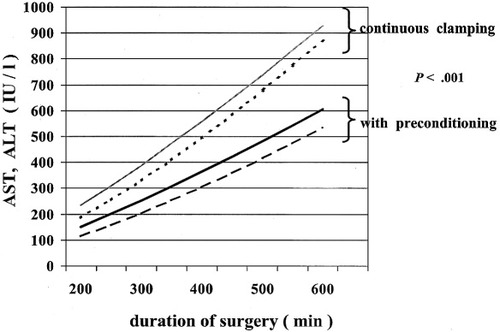

Multiple regression analysis performed on all cases by accounting simultaneously for duration of liver ischemia and for the use or non-use of preconditioning, showed that changes in AST and ALT at postoperative day 1 were directly related to duration of liver ischemia in both groups, with a highly significant decrease in AST and ALT related to the use of preconditioning (P < .01) for any given duration of ischemia.

Graphical display of regressions quantifying the relationship between changes in AST (continuous, ----; preconditioning, – –) and ALT (continuous, ----; preconditioning, ——) at postoperative day 1 and DOS in patients with preconditioning or continuous clamping alone. (P < .001 for whole regressions and each coefficient).

Extension of the regression analysis to AST and ALT for postoperative day 3 yielded weaker but still significant coefficients for the effects of preconditioning (P < .01).

These results were reconfirmed by using the changes in AST and ALT relative to preoperative values, as opposed to use of the absolute postoperative values of AST and ALT.

Discussion

Recently, the positive effects of IP on the tolerance to ischemia-reperfusion damage of the liver have been reported by Clavien et al.12 This technique, as described by Clavien et al., is based on a short period (10 minutes) of HPC, followed by an equivalent period (10 minutes) of reperfusion before the start of prolonged continuous clamping. It has been shown that, after major resection, and for up to 30 minutes of total ischemia in healthy liver, the serum levels of transaminases at postoperative day 1 were reduced more than 2-fold in patients in whom preconditioning was used, compared to patients in whom continuous clamping alone was used. In the same study, in patients in whom preconditioning was used, a significant reduction of cellular ischemic damage (expressed as a reduced number of apoptotic sinusoidal lining cells) was reported. Although the exact mechanisms are not completely known, the positive effects of IP seem to be based on the release of substances such as adenosine and nitric oxide by the ischemic tissue after the period of preconditioning; these substances significantly protect the liver against the subsequent prolonged ischemia.

The beneficial effects of intermittent HPC might be related to the same mechanism.13 The use of the preconditioning technique, which avoids repeated periods of unclamping, could be associated with a reduction of intraoperative bleeding and a decreased duration of liver resection; however, these results were not reported by Clavien et al.12 In fact, no significant differences were detected between the IP group and the continuous clamping group in terms of DOS or blood loss.12

In the present study, we decided to evaluate the effects of IP in both major and minor resections. In our experience, the beneficial effects of vascular clamping, with its reduced risk of bleeding and reduced number of transfusions, have been observed in both major and minor resections.10

Moreover, after preconditioning, we used continuous clamping for more prolonged periods of time than those reported by Clavien et al., and mean duration of ischemia was 54 minutes (range, 27-110), longer than that reported by Clavien et al. (30 minutes).12

In addition, we used the preconditioning technique in a different way: resection was started immediately (during the first 10 minutes of clamping), as is usually done when intermittent clamping is used. The resection was then interrupted during the following 10 minutes of reperfusion and started again at the subsequent continuous clamping. With this protocol, we tried to further limit the total duration of liver ischemia.

The results of our study confirm that preconditioning in healthy liver is as effective in reducing intraoperative bleeding as continuous clamping. In fact, the rates of transfused patients are similar in both groups. In addition, it is confirmed that HPC after ischemic preconditioning is well tolerated for periods longer than 30 minutes: in more than 30% of patients in whom preconditioning was used, total ischemia of the liver was longer than 60 minutes.

Furthermore, the rise of ASL and ALT in patients with IP was lower than that observed in those with continuous clamping alone. These results are even more consistent if one considers that mean duration of liver ischemia was markedly longer in patients with preconditioning than in patients with continuous clamping alone (54 vs. 36 minutes, P = .001).

It has already been widely shown that vascular clamping techniques during liver resection can significantly reduce intraoperative bleeding. In a recent randomized study, Man et al. confirmed that the Pringle maneuver is safe and effective in reducing blood loss.9 The same results were obtained in a large retrospective comparing 125 resections performed with HPC and 120 resections performed without HPC.10 Continuous clamping is generally considered safe for up to 90 minutes in healthy liver.10, 14

In another controlled study, Belghiti et al. showed that intermittent HPC (15 minutes of clamping and 5 minutes of unclamping alternated sequentially up to the end of the resection) is better tolerated than continuous HPC, particularly in abnormal liver.14 Intermittent HPC is considered safe for up to 2 hours; it is safely used in cirrhotic patients,15 and the most prolonged periods of HPC have been reported with this technique (322 minutes in healthy liver16 and 204 minutes in cirrhotic liver17). However, intermittent clamping can be associated with significantly higher blood loss during the reperfusion periods.14

The introduction of preconditioning represents a new step in the evolution of vascular clamping techniques and seems to be associated with evident benefits in comparison to continuous clamping. The present study demonstrates this as well.

In conclusion, our study confirms that IP is a safe and effective technique for vascular clamping during liver resection in healthy liver and is also better tolerated than continuous clamping alone for prolonged periods of ischemia. This technique therefore should be preferred to continuous clamping alone in healthy liver. At present, intermittent clamping remains the method of choice for warm ischemia in pathological liver, especially in cirrhotic liver. Additional studies are needed to assess the role of IP in liver resections for cirrhotic liver and to compare IP with intermittent clamping.

Finally, it is worth stressing that the use of vascular clamping techniques can only contribute to reducing the risk of intraoperative bleeding during liver resection, which remains the major risk of this surgery. In addition, accurate selection of patients, meticulous surgical technique, faultless knowledge of liver anatomy, use of intraoperative ultrasound, and expertise of both the surgical and anesthesiological teams are leading factors in obtaining a significant reduction of intraoperative bleeding during liver resection.