Lessons for a learning health system: Effectively communicating to patients about research with their health information and biospecimens

Abstract

Introduction

Sharing patient health information and biospecimens can improve health outcomes and accelerate breakthroughs in medical research. But patients generally lack understanding of how their clinical data and biospecimens are used or commercialized for research. In this mixed methods project, we assessed the impact of communication materials on patient understanding, attitudes, and perceptions.

Methods

Michigan Medicine patients were recruited for a survey (n = 480) or focus group (n = 33) via a web-based research study portal. The survey assessed the impact of mode of communication about health data and biospecimen sharing (via an informational poster vs. a news article) on patient perceptions of privacy, transparency, comfort, respect, and trust. Focus groups provided in-depth qualitative feedback on three communication materials, including a poster, FAQ webpage, and a consent form excerpt.

Results

Among survey respondents, the type of intervention (poster vs. news) made no statistically significant difference in its influence on any characteristic. However, 95% preferred that Michigan Medicine tell them about patient data and biospecimen research sharing versus hearing it from the news. Focus group participants provided additional insights, discussing values and perceptions of altruism and reciprocity, concerns about commercialization, privacy, and security; and the desire for consent, control, and transparency.

Conclusion

Developing our understanding of patient data-sharing practices and integrating patient preferences into health system policy, through this work and continued exploration, contributes to building infrastructure that can be used to support the development of a learning health system across hospital systems nationally.

1 INTRODUCTION

The sharing of patient health information or biospecimens across academic institutions, government, and industry can improve patient outcomes and accelerate breakthroughs in medical research.1 The adoption of electronic medical records (EMRs) across most medical centers has steadily increased the number of hospitals electronically exchanging patient health information for clinical purposes, with over 75% of engaged physicians reporting they “experienced improvements in quality of care, practice efficiency, and patient safety.”2

Legally, entities are allowed to share patient data and biospecimens for research purposes without express consent under certain conditions, such as if they are de-identified or the research poses low risk to individuals.3 Because of the potential benefit of such research to advancing science and medicine and the legality of such an approach, many institutions share patient data and biospecimens broadly.4 Ethics scholars have argued that patients may have a moral obligation of reciprocity to participate in low-risk research if they have benefited from receiving care improved by the research themselves,5, 6 although this is hotly contested as it applies to biomedical research, generally.7, 8 While not legally required, some hospitals share basic information about research use of patient data and biospecimens in their clinical consent forms.9

That said, patients generally do not understand whether or how their clinical health information or biospecimens are used for research, and, if they do, many report discomfort with how the current system is structured.10 Patients report particular discomfort with data or biospecimen commercialization by private entities11, 12 and have expressed concerns about who profits from their data, even when de-identified, and how those profits are used.13-15 The majority of patients want to be notified about health information and biospecimen commercialization, but very few are comfortable with such use.16, 17 However, some patients view the sale of health data as acceptable if profits are put back into public health services.12 Tiered consent approaches have been explored for different types of research,18, 19 but implementation could be challenging for hospital systems. Hospitals have counter-argued that setting up a consent process for all secondary research use of data and biospecimens would be both costly and expensive and would likely result in less data being available for research.20 Therefore, many hospitals continue such sharing, even with the knowledge that it makes some patients uncomfortable.

But, even if specific consent structures for secondary research use of health data and biospecimens are untenable, that does not mean that entities lack the moral obligation to at least notify patients about such use.21 Yet the best methods of going about such notification, and having that notification enable patients to better understand the system, have yet to be fully elucidated. This information is critical for establishing trust between patients and the medical system, a key priority identified by the National Academy of Medicine.22 Identified methods of increasing transparency and understanding for patients include detailed information on clinical informed consent forms, poster or visual campaigns, or further information on hospital websites.

The goal of this mixed methods project was to assess the impact of these communication and marketing materials on patient understanding of health data and biospecimen uses—as well as their attitudes and perceptions regarding sharing their health data and biospecimens for research—embedded within the Michigan Medicine (MM) system at the University of Michigan (U-M).23 Developing our understanding of patient data-sharing practices and integrating patient preferences into health system policy, through this work and continued exploration, contributes to building infrastructure that can be used to support the development of a learning health system across hospital systems nationally.

2 METHODS

This study employed a convergent mixed methods approach,24 merging qualitative data from Zoom focus groups and quantitative data from an online survey of MM patients. Survey respondents and focus group participants were recruited separately from the U-M Health Research (UMHR) website,25 a platform that helps connect researchers with interested volunteers for U-M research studies. Participants for this study had to be 18 years of age or older, fluent in English, and must have seen a U-M provider sometime in the past. This study was deemed exempt by U-M IRBMED (HUM00236265 and HUM00235071).

2.1 Survey

Survey respondents were asked to complete a 15-min online survey, administered via Qualtrics,26 about their perspectives and preferences toward patient health data and biospecimen sharing for research purposes. The survey was carried out between September and October 2023. Respondents received a $10.00 Amazon gift code via email for participating.

Together for tomorrow: We have the power to create breakthroughs, together

Like other hospitals around the country, Michigan Medicine uses patient health information and biospecimens to help researchers better understand diseases and health conditions. Working together we can find ways to provide better, safer, more effective health care for all. Learn more about how we protect your privacy and how you are helping to advance research at [FAQ Webpage].

Michigan Medicine uses its patients' health information and biospecimens for research. Representatives from Michigan Medicine say this advances health research, helping researchers better understand disease and health conditions and allowing them to provide better, safer, more effective health care. They also say they have measures in place to protect patient privacy.

(Appendix 1: Discussion materials). After the intervention, respondents were then asked the same set of questions as at baseline.

Finally, all survey respondents were asked to identify which potential questions about health data and biospecimen sharing they would like to have answered on a “frequently asked questions” webpage from 10 randomized options (to avoid order bias). These questions were initially generated from a group of expert stakeholders (the MM Human Data and Biospecimen Release Committee23) aligning with the kind of information the committee hypothesized that patients would want to know (Appendix 1: Discussion materials). Respondents were presented with a mock FAQ webpage with three pre-selected questions and answers. Respondents were then asked the baseline questions again (Appendix 2: Survey instrument).

2.2 Focus groups

Three 90-min facilitated focus groups of 10–12 participants were conducted in June 2023. Participants received the same two materials as the survey respondents, the: (1) informational poster, and (2) a mock-up of the FAQ webpage. In addition, focus group participants were given an excerpt from an updated MM clinical informed consent form disclosing additional information about research use of patient data and biospecimens (this consent form excerpt was not given to the survey respondents to keep the survey under 15 min and preserve focus to improve validity of results27) (Appendix 1: Discussion materials).

Participants were asked about their understanding and perspectives related to each of the materials, as well as their hopes and concerns related to health data and biospecimen sharing (Appendix 3: Focus group guide). Participants received a $50.00 gift card via mail for participating.

2.3 Analysis

Survey: We used descriptive statistics to describe respondents' demographic and baseline characteristics. We used repeated measures ANOVA to assess whether the poster or media intervention impacted respondents' characteristics, such as trust, and whether there was a difference in impact across the two interventions (poster vs. news article). The effect size was reported to illustrate the degree of intervention impact. Cohen's d effect sizes were categorized as large (≥0.80), medium (≥0.50), and small (≥0.20).28 The Spearman's rank-order correlation was also used to assess whether reading the FAQ webpage was associated with knowledge about research use of data and biospecimens. SPSS was used for all analyses, all statistical tests are two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We defined “strongly” and “somewhat agree” as the combined variable “agreed,” and “strongly” and “somewhat disagree” as the combined variable “disagreed” for purposes of this analysis (the fifth option on the Likert scale was “Neither agree nor disagree”).

Focus groups: Zoom recordings of the focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim and de-identified. Thematic analysis was performed by an experienced qualitative researcher (KAR) to summarize the important themes and identify relevant quotations. This analysis was then reviewed by the research team.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Description of study population

Sixty one percent of our final survey sample were female and 71% were White (non-Hispanic and non-Middle Eastern or North African), with a mean age of 47.5 years. As interested volunteers from the UMHR website were disproportionately women, White, and had advanced degrees, focus group participants were purposively sampled to increase gender balance and diversity of race, ethnicity, and education. Forty six percent of focus group participants were female and 45% were non-Hispanic White, with a mean age of 45.2 years (see Table 1).

| Characteristic | Survey (% or SD) n = 480 | Focus group (% or SD) n = 33 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 293 (61.0%) | 15 (45.5%) |

| Male | 180 (37.5%) | 18 (54.5%) |

| Neither of these describe me | 7 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Mean Age | 47.5 (17.4) | 45.2 (16) |

| Race (Select one) | ||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 3 (0.6%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Asian | 39 (8.1%) | 5 (15.2%) |

| Black or African American | 42 (8.8%) | 9 (27.3%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| White | 365 (76.0%) | 18 (54.5%) |

| Multi-race or other | 17 (3.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| None of these describe me | 13 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 28 (5.8%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| Middle Eastern/North African | 14 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Highest level of school completed | ||

| Less than BA | 128 (26.7%) | 7 (21.2%) |

| BA | 151 (31.5%) | 16 (48.5%) |

| More than BA | 201 (41.9%) | 10 (30.3%) |

3.2 Survey outcomes

3.2.1 Baseline

At baseline (before seeing either intervention), 60.6% (n = 291) of respondents agreed that they know how MM uses health information and biospecimens for research; 25.6% (n = 123) disagreed. In a “Select all that apply” question, half of respondents reported that they learned about it from the MM informed consent form (50%, n = 240) and one-third from a healthcare provider or researcher (34.4%, n = 165). A minority reported learning about it from an MM website or other advertising (17.1%, n = 82), or from the news (1.3%, n = 6). In addition, 75.2% (n = 361) reported they carefully read clinical forms, and those who read forms were also more likely to report knowledge (Spearman's rho = 0.193, p < 0.001). Those who reported that they were a fan of U-M sports were more likely to report trust in MM (Spearman's rho = 0.261, p < 0.0001).

The majority agreed that MM is transparent about how information and biospecimens are used for research (59.0%, n = 283). While a majority also agreed that patients should share their health info and biospecimens for health research that is low risk to them (72.3%, n = 347), almost all agreed that hospitals should tell patients how they are used (97.9%, n = 470). Respondents who reported that MM's research improves patient care were also more likely to report that patients should share their data and biospecimens (Spearman's rho = 0.197, p < 0.0001).

While the majority of respondents reported they were not concerned about their health privacy (64.4%, n = 309), nor have done anything in response to such concerns (67.7%, n = 325), a minority did report having privacy concerns (17.7%, n = 85) and having taken some action. Reported actions (presented as “select all”) included: kept some health information from their clinician (16.7%, n = 80), looked for additional information about privacy (11%, n = 53), chose a different healthcare provider (11%, n = 52), avoided seeking healthcare (8.3%, n = 40), or asked their clinician not to record or share private information (6%, n = 29).

3.2.2 Poster or media intervention

Viewing either the informational poster or the news article resulted in statistically significant decreases in trust (mean difference ± sd: −0.077 ± 0.663, p = 0.011, Cohen's d = 0.12) and comfort (−0.065 ± 0.591,p = 0.017, d = 0.11), and an increase in concern for privacy (0.163 ± 1.07, p < 0.001, d = 0.15) and perception of transparency (0.096 ± 0.8, p = 0.009, d = 0.12), but all effect sizes were small. The type of intervention (poster vs news) made no statistically significant difference in its influence on any characteristic (privacy, transparency, comfort, respect, or trust). However, 94.6% (n = 452/478) of respondents said they would rather have MM tell them about patient data and biospecimen research sharing as opposed to hearing it from another source (like on the news). U-M sports fans were more likely to report continued trust in MM both after seeing the poster (Spearman's rho = 0.205, p < 0.0001) or the news (Spearman's rho = 0.225, p < 0.0001).

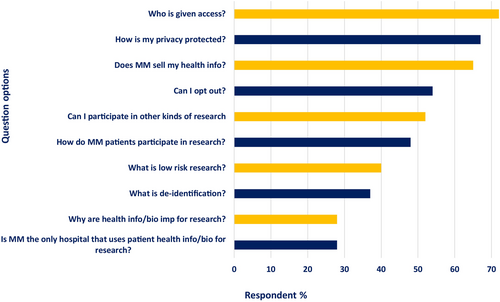

3.2.3 FAQ webpage

Half of respondents who viewed the poster reported that they would visit the FAQ webpage, advertised via QR code and a link on the poster itself (50.2%, n = 120/239); respondents who reported that they carefully read forms at baseline were more likely to do so (r = 0.231, p < 0.0001). Across both groups, a large majority of respondents wanted to know the answers to the following, select all, questions: “Who is given access?” (72.3%, n = 347), “How is my privacy protected?” (67.1%, n = 322), and “Does Michigan Medicine sell my health information?” (65.2%, n = 313). Fewer respondents wanted to know answers to contextual questions such as: “Why are health information and biospecimens important for research?” (27.7%, n = 133) and “Is Michigan Medicine the only hospital that uses patient health information and biospecimens for research?” (27.5%, n = 132) (Figure 1). After reviewing the webpage, respondents were significantly more likely to report knowledge about MM use of data and biospecimens for research (p < 0.0001).

3.3 Focus group outcomes

In the context of giving feedback on the MM communication materials (including the informational poster, consent form excerpt, and FAQ webpage), focus group participants discussed how the information in these materials might impact their relationship with MM. As they reviewed these materials, participants discussed their values and perceptions around altruism and reciprocity, commercialization, consent and control, privacy and security, and transparency as they related to MM's use of health data and biospecimens for research (Table 2: Focus Group Illustrative Quotes).

| Overarching: Impact of data sharing policies | “I don't agree with everything that was [in the materials] maybe, but I'm not going to start looking for some place else to go.” |

| “…the reality of the world is, it costs a lot more money to go somewhere if you're not insured by them or whatever, so it's a real pain. You just have to suck it up and do it, which would not make me happy and feel good about U of M Medicine.” | |

| “Ultimately, you're just forcing [patients] into this position.” | |

| Theme 1: Altruism and Reciprocity | “…without data, no research can move forward…” |

| “I'm sure that [MM] used technology and stuff that they learned prior to what they did to me from someone else, and I hope that they can use what they've gained from me to help someone else, because I do think that they are doing good work.” | |

| “…from [the poster, it] sounds like [sharing data is] to help humanity, but I have a little bit of cynicism there too like, what is this really going to be used for…?” | |

| Theme 2. Discomfort with Commercialization | “[the website] got me concerned. …I don't want someone to financially profit off my body and my specimens, my data.” |

| “I would like to know who these industry researchers are, because I would not want to give my information to certain companies. I wouldn't feel comfortable with that.” | |

| Theme 3. Consent and Control | “I feel this is absolutely wrong, that you cannot opt out of this. […] I don't like it one bit that my information is used, and I have no control over it, what it's being used for, what those studies are.” |

| “[The poster is] just a statement of fact. Not asking us to participate. Now that that's been brought up, it's kind of made me uneasy because I'm thinking like, when did I sign a waiver for this? Did I agree to this?” | |

| “If I decline to sign [the consent form], I probably wouldn't be able to get health treatment from the U of M.” | |

| Theme 4. Privacy and security | “… could you imagine if it's your specimen/ biomedical research stuff floating around…different places [with] different standards, and not all people think and feel the same?” |

| “Are they getting my name, address, birth date, mother's maiden name, and the whole nine yards?” | |

| “I didn't even know the IRB existed, so they need to let us know more about that.” | |

| Theme 5. Improving Transparency and Understanding | “I feel like a lot of institutions are doing it, but I kind of respect Michigan's transparency in doing so.” |

| “[The QR code is] a quick and easy way to get to where you want to go if you're interested in looking at more of that information.” | |

| “[The consent form is] a lot to read in one go, and I probably would read just three or four lines, and I will see that, ‘okay, they are probably going to use it for the research,’ but I might be not knowing that it could have been transferred to some third-party entities…” | |

| “I thought [the website] was clear and concise and simple. Not a lot of lawyer stuff in there to confuse you or anything…” |

3.3.1 Focus group participant views

After viewing the informational poster, the consent form excerpt, and the FAQ webpage, the majority of focus group participants expressed either positive or ambivalent attitudes toward MM. These views mirrored those of our survey respondents, who also remained largely positive toward MM after exposure to the materials. For those with more ambivalent attitudes, they expressed appreciation for MM, but were concerned about particular aspects of its approach to patient health data and biospecimen sharing (such as no opt-out and commercialization). However, most reported that they would not seek care elsewhere. Only a few participants expressed more negative views after viewing the materials and reported that they would consider seeking healthcare elsewhere if they could. One participant, however, highlighted insurance coverage and other financial challenges of seeking care elsewhere in response to this discomfort. Another participant also brought up the impact of limitations of insurance and observed that, if a patient cannot go somewhere else, patients are essentially coerced into consenting.

3.3.2 Theme 1. Altruism and reciprocity

Several focus group participants pointed out that they were aware that being a patient at a teaching and research institution means participating in research, which also may lead to benefits for oneself and others. Some participants appreciated how the informational poster emphasized helping others, but wondered about the types of research that were being conducted with their health data and biospecimens, and whether and how sharing is promoting patient health.

Some discussed being motivated by the values of altruism and reciprocity. These participants expressed the desire to support research advances that could help themselves and others. However, their support was tempered by concerns about commercialization and lack of control over what their data and biospecimens are used for.

3.3.3 Theme 2. Discomfort with commercialization

Focus group participants felt uncomfortable with the prospect of their data and biospecimens contributing to the financial benefit of researchers or commercial profit as described in the consent form excerpt and the FAQ webpage. Participants wanted more information about the commercial companies involved, as well as the policies and safeguards in place. As one participant explained, they have their own opinions about certain companies and wanted control over whether their data were shared with them.

3.3.4 Theme 3. Consent and control

Participants across all three focus groups wanted to have a choice about whether to share their health data and biospecimens. Many were surprised or dismayed that they were not being asked permission for sharing, and that they could not opt out. The poster alone, without the additional context from the FAQ webpage links, also led to some initial questions and confusion related to control and consent related to health data and biospecimen sharing.

When reviewing the consent form excerpt and FAQ webpage mock-up, focus group participants expressed concern about the loss of control over their information and biospecimens, especially when it comes to sharing data with third parties. One pointed out the coercive nature of embedding the data and biospecimen research disclosure within the clinical consent form because, without signing it, patients cannot otherwise receive care at MM. Others wanted to be able accept or reject specific aspects in the consent rather than it being an all-or-nothing approach.

3.3.5 Theme 4. Privacy and security

Like our survey respondents, focus group participants also expressed concerns about privacy and security associated with the sharing of their data and biospecimens after viewing the informational materials. They worried about whether their privacy would be protected, especially when third parties are involved. Participants wanted more information about what was being shared, who had access, and how information was kept private and secure. While some participants reported they would feel more comfortable if assured their data and biospecimens were not identifiable, others expressed concern that such procedures would not truly ensure confidentiality.

Another safeguard that focus group participants valued was the oversight by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Participants wanted additional information about the IRB, how IRB members are selected, and its research review process. Some participants suggested adding links to more information about the IRB from the FAQ webpage.

3.3.6 Theme 5. Improving transparency and understanding

Although the focus group participants had concerns about commercialization, control, and privacy, some participants pointed out that they appreciated MM's efforts toward transparency. Like our survey respondents, our focus group participants preferred being informed by MM about MM health data and biospecimen sharing.

Regarding the specific materials, focus group participants generally had a very positive response to the informational poster and perceived it to be eye-catching and easy to understand. Some participants favorably noted the perceived gender, race, and ethnic diversity of the patients represented on the poster. Some also liked the use of a QR code on the poster to redirect patients to more information on the FAQ webpage. However, a few participants misinterpreted the disclosure poster as research recruitment material, asking individuals to volunteer to donate data or biospecimens for research.

While the poster was generally well-received, with only a few expressing misunderstandings, there were more concerns about the understandability and readability of the consent form excerpt. Several participants commented that the excerpt was difficult to read or overwhelming. Some pointed out that the form used terminology that would be unfamiliar to the general public and should be edited for comprehensibility.

As compared to the consent form excerpt, focus group participants tended to view the FAQ questions on the webpage as easier to read and more accessible. However, participants also provided feedback to improve the FAQs such as further clarification about “low risk” research. Others felt that some of the FAQ answers were too long and suggested ways to make the answers easier (or more appealing) to read.

4 DISCUSSION

In this mixed methods project, we examined patient understanding, attitudes, and perceptions regarding sharing their health data and biospecimens for research through exposure to an informational poster, a FAQ webpage, and a revised consent form excerpt (focus group only). Overall, both our survey and focus group participants reported a high level of trust and comfort with MM. That trust might not always be specific to the health system—as indicated by our previous qualitative research,29 we found that being a fan of U-M sports was associated with a higher trust in the medical center, both before and after the interventions.

Consistent with previous ethical arguments for reciprocity in the learning health system,5 many survey respondents agreed that patients should contribute to low-risk research, especially those that believed that such research would translate into improved care. But almost everyone both in the survey and the focus groups reported that hospitals should tell patients this – and that they would certainly rather hear it from the hospital than from another source, like the news. Previous studies have found contrasting views on this point with some finding that a notification-only approach would be unacceptable to a majority,30 while others finding that notification is acceptable where written consent is not feasible.31 These types of findings have also been associated with self-identified race and ethnicity.32 There was also a low level of reported baseline concern for privacy, and the majority reported that they would not change behavior if they were concerned. However, a substantial minority reported potential behaviors, like keeping relevant information from their clinicians, that could have a significant impact on clinical care.33

Focusing on the clinical consent form, the majority of survey respondents subjectively reported that they knew how MM uses patient data and biospecimens for research, and that half learned it from the consent directly. But our focus group participants, who read the revised consent form excerpt as part of this research, emphasized the consent document's low readability and comprehensibility. It is hard to harmonize these two findings together. One possibility is that, because our focus group participants had lower educational attainment on average than our survey respondents, it was in fact true that our survey respondents were more likely to learn relevant information from the informed consent. Another possibility, because the survey respondents did not see the informed consent form and the focus group participants did, that the survey respondents suffered from recall bias. Or, perhaps the additional information that we added to the focus group's informed consent excerpt—intended to increase understanding and disclosure—was more likely to result in confusion. All these hypotheses warrant further review and research.

In addition, focus group participants highlighted the inherent coerciveness of requiring patients to agree to research with their data and biospecimens to receive clinical care. Our research findings continue to underscore that while patients might be conceptually supportive of contributing to minimal risk research with their clinical data and biospecimens, they remain adamant about wanting the opportunity to know and to opt-out.

Viewing the informational poster or the news article resulted in statistically significant decreases in trust and comfort, an increase in concern for privacy, and an increase in perception of transparency. That said, all findings had a small effect size. For example, while the mean of responses for “I trust Michigan Medicine” (on a 5-point Likert with “strongly agree” being 1) rose by 0.07, which was statistically significant, the average response went from a mean of 1.66 (between “strongly agree” (1) to “agree” (2)) to 1.74 (remaining between “strongly agree” and “agree”). None of the other characteristics (comfort, privacy, or transparency) with significant differences made a categorical difference either—suggesting little to no clinical impact of the results. Thus, while an argument against increased transparency about research use of data and biospecimens has been that it would impact patient care or the reputation of the hospital among patients, those concerns were not reflected in our data in a policy-relevant manner.

And, while a significant majority of survey respondents reported that they would rather hear about research use of their data and biospecimens from MM as opposed to another source, we did not find any significant difference in reported characteristics across interventions (e.g., respondents were no more likely to report decreased comfort if they learned about research use from the news versus the institution itself). This is likely because of the homogenous nature of our survey respondents, a high baseline rate of comfort and trust, and the neutral framing of the hypothetical news article. Often, when hospital data or biospecimen sharing policies are covered by media it is framed as a scandal, like the expose on Google's “Project Nightengale,” in which it collected millions of fully identified medical records from hospitals associated with Ascension.34 While we intentionally chose to keep our hypothetical news article neutral—to focus our analysis on the comparison of modes of communication as opposed to content—it is highly likely that a negative news article would have had a greater impact.

Participants in the focus groups were also confused by the difference between transparency regarding how MM is already using their data and biospecimens for research and optional research recruitment (which also is often advertised by poster throughout the MM hospital). Their responses also underscored the inherent tension between designing an informational poster that will attract patient attention (i.e. with large photos of patient faces and minimal text) and wanting to immediately understand more detailed information (which would have required the inverse). Given this feedback, an image-centric poster that can immediately link to additional information on a website, might remain the right balance.

Promisingly, we found that reviewing the FAQ webpage was associated with a significant increase in subjective knowledge regarding MM research use of patient data and biospecimens in our survey respondents. Respondents were also most likely to report interest in questions regarding access to data and biospecimens, whether access is sold, and how patient privacy is protected. They reported less interest in questions that might provide helpful context into why the institution makes certain choices, such as why health data and biospecimens benefit research and whether MM is the only hospital that uses patient data in this way. These considerations seem to emphasize the importance of including contextual information on a permanent platform, such as the website's landing page, to ensure that it is continually available to users and does not require an additional “click” to reveal. Additional information regarding advances research has achieved would also likely add to such context and reinforce respondents' already high levels of reported altruism.

Focus group participants also reported both appreciating succinct answers to questions but also wanting to know all relevant information beneath whichever “accordion”-style question (i.e., the answer only appeared if the user selected the question) they selected—which might be improved by additional linking between answers. Participants also described reassurance regarding IRB oversight and the potential benefit of additional information and reassurances about review processes.

This study had limitations. First, the survey cohort was largely well-educated White women. In addition, when studying patient perspectives on enrolling in research, one inherently must rely on a cohort that has consented to research. These two factors combined suggest our research sample consisted of people who already have a high baseline trust of MM and are supportive of research overall. That said, we were able to purposively sample our focus group participants for more diverse input over gender, race, ethnicity, and education—and the findings from the focus group supported many of those from the survey. Second, while past studies have found differences in perspectives on enrolling in secondary research across race and ethnicity,32, 33, 35 we did not observe the same pattern of results, likely due to the homogenous nature of our cohort. Third, the poster and news article differed in imagery and language, which might have impacted results.

5 CONCLUSION

In this mixed methods project with survey respondents and focus group participants, we assessed the impact of a new campaign at a major academic medical center to promote transparency regarding how patient data and biospecimens are used for research. We found that while most survey respondents agreed patients should share data and biospecimens for minimal-risk research, almost all reported that hospitals should tell patients how they are used. After reviewing an informational poster or hypothetical news article disclosing how the hospital uses patient data and biospecimens, survey respondents reported no policy-relevant change in concerns for privacy, transparency, comfort, respect, or trust. But the vast majority reported they would rather learn this information from the hospital than the news. Our focus group participants also expressed largely favorable or ambivalent views after reviewing the same material and discussed related values—such as altruism and reciprocity—in depth. These findings can help inform hospitals acting as learning health systems to use validated methods to increase transparency and predict patient response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (R01TR004244, UM1TR004404), the National Cancer Institute (R01CA214829), and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R01EB030492).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no relevant conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data is publicly available via OpenICPSR, the open-access data repository of the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan.