Indwelling voice prosthesis insertion after total pharyngolaryngectomy with free jejunal reconstruction

Study location: This work was performed at the Division of Head and Neck, Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation of Cancer Research, Tokyo, Japan.

Abstract

Objectives

Total pharyngolaryngectomy with free jejunal reconstruction is often performed in patients with hypopharyngeal carcinoma. However, postoperative speechlessness significantly decreases patient quality of life. We investigated whether Provox® insertion could preserve speech after total pharyngolaryngectomy with free jejunal reconstruction.

Study Design

Retrospective chart review.

Methods

A total of 130 cases of secondary Provox® insertions after total pharyngolaryngectomy with free jejunal reconstruction were analyzed. Communication outcomes were compared using the Head and Neck Cancer Understandability of Speech Subscale. Outcomes and complications associated with insertion site (jejunal insertion vs. esophageal insertion) and adjuvant irradiation therapy were also evaluated.

Results

Provox® insertion had favorable communication outcomes in 102 cases (78.4%). Neither the insertion site nor irradiation affected the communication outcome. Complications were observed in 20 cases (15.4%). Local infection was the most common complication. Free jejunal insertion, in which the resection range was enlarged, had a lower complication rate than did esophageal insertion, and its complication rate was unaffected by previous irradiation. For all patients, the hospitalization duration and duration of speechlessness were 13.4 days and 14.6 months, respectively. Patients receiving jejunal insertions had a significantly shorter hospitalization duration than did those receiving esophageal insertions. Unlike Provox®2, Provox®Vega significantly reduced the complication rate to zero.

Conclusion

For jejunal inserson of a Provox® prosthetic, a sufficient margin can be maintained during total pharyngolaryngectomy and irradiation can be performed, and satisfactory communication outcomes were observed. Provox® insertion after total pharyngolaryngectomy with free jejunal reconstruction should be considered the standard therapy for voice restoration.

Level of Evidence

4.

INTRODUCTION

Reconstruction with a free revascularized jejunal autograft is performed after total pharyngolaryngectomy (TPL) in patients with advanced laryngeal carcinoma, hypopharyngeal carcinoma, or cervical esophageal carcinoma.1-3 Loss of speech after laryngectomy can significantly decrease patients' quality of life (QOL).4 There are three main methods of voice restoration: usage of an electrolarynx, esophageal speech, and tracheal-esophageal shunt speech using an indwelling voice prosthesis4 inserted primarily or secondarily.5 Voice restoration is more challenging after TPL than after total laryngectomy (TL). Achieving esophageal speech is especially problematic after TPL because of difficulties in producing sounds in the absence of the pharyngeal constrictor and hypopharyngeal mucosa, which are used to construct a new sound source.

The gold standard for TL patients is indwelling voice prosthesis insertion via a tracheal-esophageal puncture.4 Although this procedure is becoming more widespread in patients who undergo TPL with free jejunal reconstruction,6-8 it has been performed in only 10%–20% of such patients in Japan (clinical observations). This might be because the potential complications associated with aggressive treatments such as irradiation and extensive surgery are unknown.

Several studies have reported on the use of prosthetics for voice restoration following TPL.6, 7, 9-11 However, most of these were small case series or included various reconstruction methods. Therefore, the features and complications of an indwelling voice prosthesis in patients who undergo TPL with free jejunal reconstruction have not been established in large cohorts. The aim of the present study was to determine the features and complications associated with secondary indwelling voice prosthesis insertion after TPL with free jejunal reconstruction. We inserted the indwelling voice prosthesis in 130 patients using the same technique and retrospectively analyzed communication outcomes and complications associated with irradiation and the TPL resection range.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. We reviewed 130 consecutive patients who underwent indwelling voice prosthesis insertion following TPL with free jejunal reconstruction at the Department of Head and Neck Surgery, Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, between July 2005 and May 2015. Various sizes of Provox®2 (8-mm, 10-mm, 12.5-mm, and 15-mm) and Provox®Vega (12.5-mm) (Atos Medical, Malmö, Sweden) indwelling voice prostheses were inserted several months after TPL under general anesthesia (secondary insertion). Surgery was conducted according to the modified methods of Hilgers and Schouwenburg.12 Modifications included using a ventilation tube and flexible fiberscope in place of a rigid esophageal scope to minimize intra-jejunal bleeding. The Provox Vega Puncture Set was used when Provox®Vega inserted.13 The mean operative duration was 13.8 min (range, 5–26 min). The surgical procedure is presented in the video in the appendix.

Patient characteristics, communication outcomes after Provox insertion, the complication rate, and factors associated with complications, including prosthesis size, were investigated. Communication outcomes were assessed by an independent speech pathologist or head and neck surgeon. Speech intelligibility was rated categorically according to the Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer (PSS-HN) Understandability of Speech Subscale as follows: 100, understandable all the time; 75, understandable most of the time with occasional repetition necessary; 50, understandable with face-to-face contact; 25, difficult to understand; and 0, never understandable and may use written communication.14 The success rate of prosthetic voice restoration was determined by the percentage of the patients with scores of 100 or 75.

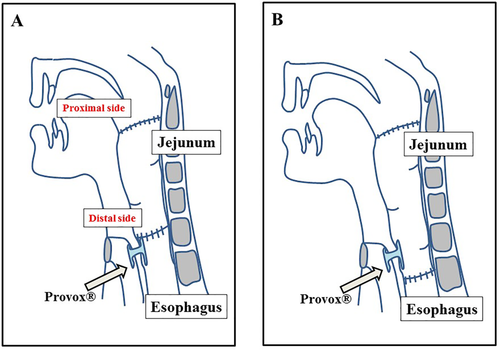

In this series, jejunal or esophageal insertions were used as to determine the extent of resection for TPL (Fig. 1). Distal side resection may affect Provox® function and result in severe complications such as mediastinitis. In a preliminary analysis, this was not the case for proximal side resection. Therefore, we focused on the distal side resection pattern as a candidate index for TPL extension. If the TPL resection was not extended, the back of the membranous portion of the trachea was the residual cervical esophagus (Fig. 1A). If the TPL resection was extended, the back of the membranous portion of the trachea was the grafted jejunum (Fig. 1B). Thus, extended resection was required in cases of jejunal insertion but not in cases of esophageal insertion.

Schema of Provox® voice prosthesis insertion into the free jejunum or esophagus. (A) Esophageal insertion. If the distal end of the resection is not extended, the back of the membranous portion of the trachea represents the residual cervical esophagus, and the Provox® is inserted into the esophagus. (B) Free jejunal insertion. If the distal end of the resection is extended, the back of the membranous portion of the trachea represents the grafted jejunum, and the Provox® is inserted into the grafted jejunum. Jejunal insertion was defined as extended resection of the distal side, and esophageal insertion was defined as non-extended resection.

Statistical analyses were performed using StatMate IV software (ATMS Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher's exact test were used. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the patients' characteristics. Tumors recurred in some patients after concurrent chemoradiotherapy or radical radiotherapy, and all patients underwent TPL. The insertion site depended on the resection range of the TPL with almost two-thirds of patients undergoing esophageal insertion. The mean observation period after Provox® insertion was 57 months (range, 2–116 months). Complications included local infection, leakage, stoma stenosis, and spontaneous extrusion. Local infection was the most frequent complication, but was resolved with treatment and was non-lethal. The 5-year overall survival rate was 85.3%, this higher survival rate suggested that indwelling voice prosthesis insertion did not decrease the survival rate. Patient and procedural characteristics did not significantly affect patient survival.

| Age (years) | 61.3 (range, 38–80) | Cases (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 113 | (86.9) |

| Female | 17 | (13.1) | |

| Primary lesion | Hypopharynx | 120 | (92.4) |

| Larynx | 5 | (3.8) | |

| Cervical esophagus | 5 | (3.8) | |

| T | 1 | 0 | (0) |

| 2 | 28 | (21.5) | |

| 3 | 47 | (36.2) | |

| 4 | 36 | (27.7) | |

| Unknown | 19 | (14.6) | |

| N | 0 | 31 | (23.7) |

| 1 | 17 | (13.0) | |

| 2a | 1 | (0.8) | |

| 2b | 46 | (35.7) | |

| 2c | 14 | (10.7) | |

| 3 | 2 | (1.5) | |

| Unknown | 19 | (14.6) | |

| Stage | I | 0 | (0) |

| II | 11 | (8.5) | |

| III | 25 | (19.2) | |

| IV | 76 | (58.5) | |

| Unknown | 18 | (13.8) | |

| Primary TPL | Our institution | 87 | (66.9) |

| Other institutions | 43 | (33.1) | |

| Irradiation | Irradiation | 68 | (52.3) |

| Non-irradiation | 62 | (47.7) | |

| Puncture site | Jejunum | 46 | (35.4) |

| Esophagus | 84 | (64.6) | |

| Complications | One or more | 20 | (15.4) |

| None | 110 | (76.1) | |

- TPL = total pharyngolaryngectomy.

Communication Outcomes of Provox® Insertion after TPL with Free Jejunal Reconstruction

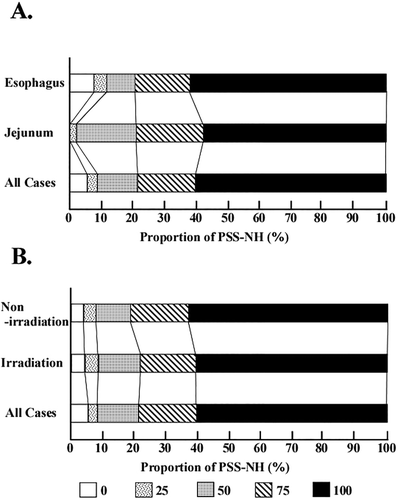

Among the 130 patients in our study, 79 (60.7%) scored 100 and 23 (17.7%) scored 75 on the PSS-HN questionnaire. The success rate of prosthetic voice restoration was 78.4%. Among the 46 patients with jejunal insertions, 27 (58.7%) scored 100 and 9 (19.5%) scored 75; the success rate was 78.2%. Among the 84 patients with esophageal insertions, 52 (61.9%) scored 100 and 14 (16.7%) scored 75, the success rate was 78.6%. Therefore, communication outcomes were similar regardless of the insertion site (Fig. 2A).

Communication outcomes following Provox® insertion. Communication outcomes were measured by using the Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer (PSS-HN) Understandability of Speech Subscale at the patient's last follow-up visit before disease progression. (A) PSS-HN scores according to insertion site. (B) PSS-HN scores according to irradiation status.

Among the 68 patients who underwent irradiation, 41 (60.3%) scored 100 and 11 (16.1%) scored 75, the success rate was 76.4%. Among the 62 patients who did not undergo irradiation, 38 (61.3%) scored 100 and 13 (20.9%) scored 75; the success rate was 82.2%. Therefore, the communication outcomes were similar irrespective of irradiation therapy (Fig. 2B).

Differences in Complication Rates between Jejunal and Esophageal Insertions

Complications were observed in 20 of the 130 patients (15.4%) in our study. Local infection was the most common complication, and other complications included leakage, stenosis, and spontaneous extrusion. Severe complications such as mediastinitis, cervical cellulitis, or septicemia were not observed, and there were no mortalities. As shown in Table 2, three of the 46 patients (6.5%) with jejunal insertions and 17 of the 84 patients (20.2%) with esophageal insertions experienced complications after insertion. The difference in the complication rate between these cohorts was significant (p < 0.05). Two of the 46 patients (4.3%) with jejunal insertions and 14 of the 84 patients (16.6%) with esophageal insertions experienced local infection; this difference was also significant (p < 0.05).

| Jejunum (%) | Esophagus (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Any complication Local infection |

6.5 (3/46) | 20.2 (17/84) | p < 0.05 |

| 4.3 (2/46) | 16.7 (14/84) | p < 0.05 |

Differences in Complication Rates According to Irradiation Status

There is no consensus on the effect of irradiation on the complication rate of Provox® insertion.5, 15, 16 The complication rates according to irradiation in all patients and the jejunal or esophageal insertion cohorts were investigated. As shown in Table 3, in the overall population and the jejunal insertion cohort, there were no significant differences in complication or local infection rates between patients who did or did not undergo irradiation. However, in the esophageal insertion cohort, irradiated patients had significantly higher complication and local infection rates than did non-irradiated patients (both p values < 0.05).

| Irradiation (%) | Non-irradiation (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All case | Any complication | 25.9 (14/54) | 12.5 (4/32) | n.s. |

| Local infection | 20.4 (11/54) | 9.4 (3/32) | n.s. | |

| Jejunum | Any complication | 8.3 (2/24) | 0.0 (0/18) | n.s. |

| Local infection | 8.3 (2/24) | 5.6 (1/18) | n.s. | |

| Esophagus | Any complication | 40.0 (12/30) | 7.1 (1/14) | P<0.05 |

| Local infection | 30.0 (9/30) | 21.4 (3/14) | P<0.05 |

The Effects of Irradiation and Insertion Site on Hospitalization Duration

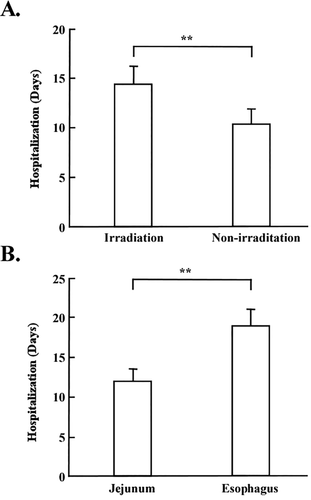

The overall mean hospitalization duration was 13.4 days. Patients who underwent irradiation were hospitalized for 14.1 days, and those who did not undergo irradiation were hospitalized for 11.8 days; this difference was significant (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, patients with esophageal insertions were hospitalized for a significantly longer times (18.2 days) than were those with jejunal insertions (12.4 days; Fig. 3B).

Required hospitalization for secondary Provox® insertion. (A) Hospitalization times of patients with or without irradiation. (B) Hospitalization times of patients with jejunal insertion or esophageal insertions.

The Effect of Irradiation and Insertion Site on the Duration of Speechlessness

Overall, there were no differences in the duration of speechlessness between patients who did or did not undergo irradiation (14.2 vs. 14.8 months). However, subgroup analysis revealed that the duration of speechlessness was significantly longer in patients who underwent postoperative irradiation than in those who underwent preoperative irradiation (18.8 vs. 12.6 months). There were no significant differences in the duration of speechlessness according to insertion site: patients with jejunal insertion were speechless for 14.1 months, and those with esophageal insertion were speechless for 15.1 months.

Differences in Complication Rates According to Device Size

We sequentially used 8-mm or 10-mm Provox®2 prostheses (Size A), 12.5-mm or 15-mm Provox®2 prostheses (Size B), and 12.5-mm Provox®Vega prostheses (Size C). As shown in Table 4, eight of the 29 patients (27.6%) with a Size A device and 12 of the 77 patients (15.6%) with a Size B device experienced complications (p < 0.05). None of the patients with a Size C device experienced complications. Seven of the 29 patients (24.1%) with a Size A device and nine of the 77 patients (1.3%) with a Size B device developed local infections (p < 0.05).

| Size A | Size B | Size C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any complication | 27.6 (8/29) | 15.6 (12/77) | 0.0 (0/13) | P<0.05 |

| Local infection | 24.1 (7/29) | 1.3 (9/77) | 0.0 (0/13) | P<0.05 |

DISCUSSION

In the present study, all patients underwent secondary indwelling Provox® insertion. Primary insertion has the advantage of allowing the patient to speak immediately after surgery, but major complications such as saliva leakage around the prosthesis, mediastinitis, cervical cellulitis, and aspiration of the prosthesis have been reported.17, 18 Following TL, secondary insertion has been shown to have similar success rates (i.e., communication outcomes) as does primary insertion;15, 19 however, the outcomes and complications following TPL have not been investigated fully.20 Of particular interest was whether the need for Provox® insertion would restrict the primary therapeutic strategy (i.e., the extent of resection or multimodal therapy) because hypopharyngeal carcinomas and cervical esophageal carcinomas often require aggressive treatments.1

In the present study, the success rate of prosthetic voice restoration (78.4%) was very satisfactory and was similar to rates previously reported after TL.5, 21, 22 This suggests that secondary Provox® insertion could be a useful tool for voice restoration following TPL with free jejunal reconstruction. A previous study showed that irradiation therapy was not a contraindication to primary indwelling prosthesis insertion5 and did not decrease the success rate of Provox® insertion after TL.16 However, following extensive resection such as that used in TPL, secondary insertion might be preferable especially in previously irradiated patients because of the risk of peristomal and fistula wall necrosis.5, 23 Aside from showing that voice restoration with indwelling voice prostheses is achievable for patients following TPL with free jejunum reconstruction. One of the concepts that make this study even more valuable is that we have divided the patient population according to the puncture site, i.e., a jejunal insertion or an esophageal insertion. With regards to voice outcomes this differentiation is not important: patients with jejunal insertion did as good as patients with esophageal insertion and there were also no differences in voice outcomes between radiated and non-radiated patients. Our findings demonstrate that adjuvant irradiation therapy and extended surgery do not adversely affect communication outcomes following secondary Provox® insertion after TPL with free jejunal reconstruction.

Disadvantages of secondary insertions compared with primary insertions include additional hospitalization time and increased duration of speechlessness. In the present study, the hospitalization duration was 13.4 days. It is not clear whether extended hospitalization significantly impacted patient QOL, but none of the patients expressed dissatisfaction following the procedures. The hospitalization duration was significantly longer in irradiated vs. non-irradiated patients and in those receiving esophageal insertions vs. jejunal insertions. Owing to the potential risk of complications, as evidenced by our clinical observations, careful observation of patients undergoing irradiation or esophageal insertions is warranted.

The duration of speechlessness in our study was 14.2 months, which is similar to that reported in a previous study.24 It was longer in patients who underwent postoperative irradiation than in those who underwent preoperative irradiation. This would be expected since the need for postoperative therapy would delay the time to subsequent insertion and therefore extend the duration of speechlessness. As information about when secondary insertion should take place is limited, unforeseen delays are also possible. Because speechlessness after TL can substantially impair QOL, future studies and treatment goals should focus on determining the shortest period in which secondary Provox® insertion can be performed to minimize the duration of speechlessness.

In the present study, early insertion-related complications were rare, and the majority included local infections that could be easily managed with appropriate treatment such as debridement and administration of antimicrobial agent. Other mild complications included leakage, stenosis, and spontaneous extrusion. Severe complications such as mediastinitis, cervical cellulitis, or septicemia were not observed, and there were no mortalities. Furthermore, the complication rate was significantly lower than that seen in previous studies.19, 25 In the study by Moon et al., 43% of patients undergoing tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) experienced TL-related complications, with no difference in complication rates between primary vs. secondary TEP.19 In the study by Boscolo-Rizzo et al., complications occurred in 20.3% and 16.7% of patients undergoing primary and secondary TEP after TL, respectively.25 Our results regarding complications attest to the safety of secondary Provox® insertion after TPL with free jejunal reconstruction.

Irradiation did not affect the complication rate of secondary Provox® insertion, thus indicating that pre- and post-TPL adjuvant therapy is acceptable. However, the important observation is that patients with jejunal insertion had significantly lower complication rates (leakage, stenosis, spontaneous extrusion, but mostly local infections) than patients with esophageal insertion. This finding is somewhat counterintuitive, and thus all the more relevant. Moreover, in the esophageal insertions cohort, radiated patients had significantly more local infections than non-radiated patients, whereas this was not the case in the jejunal insertions cohort. Hospitalization time was also more unfavorable (longer) for irradiated and for esophageal insertion patients. The reasons for this difference are not clear; however, it is possible that reduced blood flow in the residual esophagus compromises natural immunity. To control recurrence of aggressive diseases such as hypopharyngeal carcinoma and cervical esophageal carcinoma, the paratracheal and esophageal sites are radically dissected,26 which might suppress the blood flow around the residual esophagus. On the other hand, the autografted jejunum has a sufficient blood flow because it has its own vascular system.27 The fact that jejunal insertion has a lower complication rate than does esophageal insertion is suitable for hypopharyngeal carcinoma treatment, which requires extended resection. The duration of speechlessness appeared to be significantly longer in patients who had postoperative irradiation might reflect physician's reluctance to perform indwelling voice prosthesis insertion in such patients because of fear for complications. This study clearly shows that this reluctance is only partly founded and hopefully these positive data will decrease the “speechlessness” duration in this patient population in the future.

Lastly, we evaluated the influence of the device size and type on communication outcomes and complications. Along the improvements in the Provox® device, the complication rate strikingly decreased and was zero when the most advanced device (Provox®Vega) was used. Actually, we could not find the factors decreased the complication in novel devices. But, we used the special disposable puncture tools were used for low traumatic procedure, these progressions would support the decrease in complication rates. Hilgers et al. found that Provox®Vega was quickly and easily inserted in the vast majority of cases and that no other devices were required.13 Hence, use of Provox®Vega would lower the costs associated with complications and hospitalization, in addition to potentially reducing the duration of speechless.

CONCLUSION

For secondary Provox® insertion planning, the present findings suggest that a sufficient safety margin can be maintained for TPL and that full adjuvant therapy can be performed for aggressive carcinoma. Although further studies comparing communication outcomes and complication rates between primary and secondary insertions are required, we propose that secondary Provox® insertion after TPL with free jejunal reconstruction should be considered the standard therapy for voice restoration.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed at and funded internally by the Division of Head and Neck, Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation of Cancer Research, Tokyo, Japan. The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.