Outcomes of Cochlear implantation in early-deafened patients with Waardenburg syndrome: A systematic review and narrative synthesis

Abstract

Objective

This systematic review aims to establish the expected hearing and speech outcomes following cochlear implantation (CI) in patients with profound congenital deafness secondary to Waardenburg syndrome (WS).

Methods

A systematic review of the literature and narrative synthesis was performed in accordance with the PRISMA statement. Databases searched: Medline, Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Collection, and ClinicalTrials.gov. No limits were placed on language or year of publication.

Results

Searches identified 186 abstracts and full texts. Of these, 16 studies met inclusion criteria reporting outcomes in 179 patients and at least 194 implants. Hearing outcomes of those receiving cochlear implantation were generally good. Five studies included genetic analysis of one or more of the participants. A total of 11 peri/post-operative complications were reported. The methodological quality of included studies was modest, mainly comprising noncontrolled case series with small cohort size. All studies were OCEBM grade III–IV.

Conclusion

Cochlear implantation in congenitally deafened children with Waardenburg Syndrome is a well-established intervention as a method of auditory rehabilitation. Due to the uncommon nature of the condition, there is a lack of large-scale high-quality studies examining the use of cochlear implantation in this patient group. However, overall outcomes following implantation are positive with the majority of patients demonstrating improved audiometry, speech perception and speech intelligibility supporting its use in appropriately selected cases.

1 INTRODUCTION

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) is an inherited disorder defined by hypopigmentation of the skin, hair, and irides and a varying degree of sensorineural hearing loss. It was first described by the Dutch ophthalmologist, Petrus Waardenburg, in 1951 highlighting features now defining WS type I: dystopia canthorum, hypopigmentation of the forelock, heterochromic irides and synophrys.1 WS type II is variation on these clinical features, with the absence of dystopia canthorum, and is divided into subtypes A-D based on the type of genetic mutation. WS type III is the addition of musculoskeletal abnormalities to features defining WS type I. Finally, WS type IV is the addition of Hirschsprung disease to WS type II features. The overall prevalence of Waardenburg syndrome in the general population is estimated at 1 in 40,0002 with WS type I and II being the most common.3

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is a commonly reported feature of WS, with a prevalence of over 70%.4 The extent of hearing loss can be variable, even within families, ranging from profound deafness to a progressive postlingual hearing loss.5, 6 A systematic review by Song et al.4 demonstrated that hearing loss was almost exclusively sensorineural and that almost 90% of patients suffer from bilateral hearing loss. They also highlight an association between different disease-causing genes and the auditory phenotype. It is acknowledged that mutations in PAX3 are associated with WS type I and III,4, 7, 8 MITF with WS type II only,4, 9, 10 and SOX10 with WS type II and IV.4, 8, 11 Hearing loss is found in over half of patients with a PAX3 mutation and 90% of patients with SOX10 or MITF mutations. The SOX10 mutation is associated with more severe hearing loss with the majority of cases having profound congenital deafness compared to just 60% for MITF mutations.4

The degree of hearing loss observed is more related to the underlying genetic mutation rather than clinical classification as PAX3, SOX10, and MITF have all been shown to play a role in inner ear function in either human or animal models via various mechanisms.12-14

Anatomical variations of the inner ear are frequently identified in patients with WS being present in up to 50% of cases.15-18 Commonly reported inner ear abnormalities include vestibular aqueduct enlargement, widening of vestibule, internal auditory canal hypoplasia, decreased modiolus size and aplasia or hypoplasia of the posterior semicircular canal seen in roughly 26% of cases.19 Of note, temporal bone abnormalities may be more strongly associated with a SOX10 mutation phenotype.20

In cases of profound congenital deafness cochlear implantation may be considered. This systematic review aims to examine the current literature to identify what are the expected hearing and speech outcomes following cochlear implantation (CI) in patients with a diagnosis of Waardenburg syndrome (WS)?

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Population: The participants included were children or adults with Waardenburg syndrome causing profound hearing loss.

Intervention: The intervention was cochlear implantation. No restrictions were placed on implant device or method of insertion.

Comparison: No formal comparison group was used as hearing function was not expected to change without implantation. However, any comparison to other indications for CI was noted.

Outcomes: The primary outcomes were pre- and post-implantation audiometric outcomes using audiometry and/or speech perception and/or speech production. Where pre-implantation outcomes were not available, post-implantation audiometric outcomes were analyzed only. The secondary outcomes considered were genetic analysis, pre-implantation radiological findings and intra- or post-operative complications.

2.2 Study inclusion criteria

Clinical studies of cochlear implantation in patients with Waardenburg Syndrome with hearing outcomes reported at a minimum of 3 months post implantation were included. Diagnosis of WS may be clinical or genetic and of any subtype. Human studies of any methodology other than case reports or case series <3 patients were included. Studies without report of postoperative audiometric outcomes or where the abstract or full text were unavailable were excluded.

2.3 Search strategy

Searches were initially performed by our information specialist librarian and subsequently repeated by ME, and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (AL/ME). The following databases were searched: Medline, Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Collection, ClinicalTrials.gov (via Cochrane).

- “Cochlear Implants”

- “Cochlear Implantation”

- Cochlear Implant* (title)

- 1 OR 2 OR 3

- “Waardenburg syndrome”

- Waardenburg* (title)

- EDN3, EDNRB, MITF, PAX3, SNAI2 and SOX10

- 5 OR 6 OR 7

- 4 AND 8

No limit was placed on language or year of publication.

2.4 Selection of studies

Two reviewers (AL/ME) independently screened all records identified from the database searches. Studies describing cochlear implantation in patients with WS were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with any disagreement resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (CM). Studies without an accessible abstract or full text after the title/abstract screening were followed up by attempting to contact the study authors. If they remained unavailable the study was excluded. Studies were excluded if they did not report post intervention audiometric outcomes at a minimum of 3 months post procedure. Studies presenting overlapping populations were limited to the largest study sharing data. Potentially relevant studies highlighted from the initial searches and abstract screening underwent full-text screening by two independent reviewers (AL/ME) prior to data extraction. Conflicts on the selection were resolved by discussion between the reviewers.

2.5 Data extraction

Data was extracted by the first reviewer (AL) and then checked by a second reviewer (ME). Extracted data was collected in a spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft Corp, WA, USA). The data of interest comprised of location, study design, participant characteristics (including age at implantation, WS subtype, genetic analysis, and anatomy on imaging), intervention characteristics (including operative technique, implant type and perioperative complications), and primary outcome data (including follow-up timeframe).

2.6 Risk of bias quality scoring

Two reviewers (AL/ME) independently assessed the risk of bias using the Brazzelli Risk of Bias Tool for NonRandomized Studies.21 Studies were also graded according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine Grading System.22 Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (CM).

2.7 Synthesis of results

Study results have been presented by outcome measures. Additional study characteristics and findings of WS subtype, genetic analysis and radiological findings have been collated. No meta-analysis was undertaken due to the heterogeneity in methodology and outcome measures reported between and within studies.

3 RESULTS

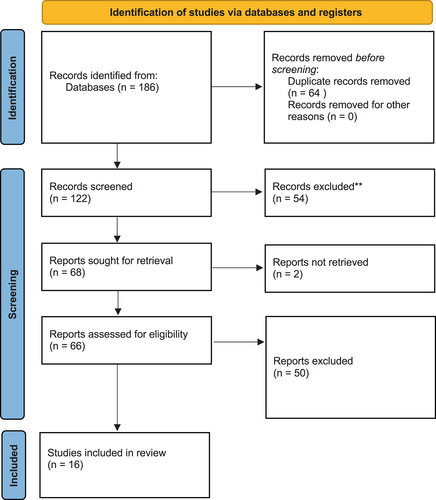

Searches were initially run 10/05/2020 and repeated 25/07/2022. A flowsheet detailing study selection according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines is included in Figure 1.23

3.1 Description of studies

Sixteen studies met the inclusion criteria with a total of 179 patients and at least 194 implants. There were nine case series, two case–control, and five cohort studies; all included between three and 30 WS patients. All studies were published between 2000 and 2022. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.15, 24-38

| Study | Year | Country | No. of patients | Population | Age at implantation (months) | WS subtype | Genetic analysis | Radiology findings | Study type | OCEBM grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daneshi et al. | 2004 | Iran | 6 | Children | 78 (24–175) | I (4), II (1), III (1) | Not specified | No abnormality | Retrospective case series | IV |

| Migirov et al. | 2005 | Israel | 5 | Children | 58 (12–187) | I (4), II (1) | Not specified | No abnormality | Retrospective case series | IV |

| Cullen et al. | 2006 | USA | 7 | Children | 37 (16–64) | Not specified | Not specified | ELS enlargement (1) PSC aplasia (1) |

Retrospective case series | IV |

| Pau et al. | 2006 | Australia | 20 | Children | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Retrospective cohort | III |

| Deka et al. | 2010 | India | 4 | Children | 64 (18–120) | I (2), II (2) | Not specified | No abnormality | Retrospective case series | IV |

| Amirsalari et al. | 2011 | Iran | 6 | Children | 26 (11–51) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Prospective cohort | III |

| Kontorinis et al. | 2011 | Germany | 25 | Children | 71 (13–180) | I (8), II (8), III (3), N/A (6) | Not specified | Enlarged vestibule (1) | Retrospective case–control | III |

| de Sousa Andrade et al. | 2012 | Portugal | 7 | Children | 30.6 (19–42) | I (6), II (1) | MITF (1) | Enlarged vestibule + semicircular canals (1) | Retrospective cohort | III |

| El Bakkouri et al. | 2012 | France | 30 | Children | 57.6 (16–192) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Retrospective cohort | III |

| Broomfield et al. | 2013 | UK | 10 | Children | 53 (14–167) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Retrospective case series | IV |

| Magalhães et al. | 2014 | Brazil | 10 | Mixed | 44 (18–264) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Retrospective case series | IV |

| Koyama et al. | 2016 | Japan | 5 | Children | 35 (21–75) | I (3), II (1), IV (1) | PAX3 (1) | IP-2 (2) | Retrospective case series | IV |

| van Nierop et al. | 2016 | Netherlands | 14 | Children | 19 (12–31) | I (3), II (10), IV (1) | MITF (3), PAX3 (1) | IP-2 (1) EVA (3) Hypoplastic SSC (1) |

Retrospective case–control | IV |

| Clarós et al. | 2019 | Spain | 22 | Children | 23.5 (12–36) | I (12), II (3), III (4), IV (3) | PAX3 (16), SOX10 (1), EDN3 (1), SNA12 (1), EDNRB (1), SW2B (1), SW2C (1) | EVA (2) IP-2 (1) CCD (1) |

Retrospective cohort | III |

| Polanski et al. | 2020 | Brazil | 3 | Children | 21.6 (21–22) | I (2), II (1) | Not specified | Not specified | Retrospective case series | IV |

| Fan et al. | 2022 | China | 5 | Children | 12 (8–21) | I (3), II (1), IV (1) | PAX3 (3), SOX10 (2) | Dysplastic SSC (1) CH-IV |

Retrospective case series | IV |

- Abbreviations: CCD, common cavity deformity; CH-IV, cochlea + hypoplastic middle and apical turns; ELS, endolymphatic sac; EVA, enlarged vestibular aquaduct; IP-2, incomplete partition type 2; PSC, posterior semicircular canal; SSC, superior semicircular canal.

3.2 Demographics

Fifteen studies included pediatric patients only, one study included both children and adults.26 The average age at time of cochlear implantation ranged from 12 months to 6.5 years; the oldest patient included was 22 years old. One study did not report the age at implantation.33 Thirteen studies reported on the type of implant used.15, 24-32, 37, 38 Reporting on WS type was variable, with 10 studies specifying the subtype of the condition based on clinical manifestation of the syndrome.24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 32, 34, 37, 38 Five studies reported on genetic analysis in 29 patients following identification of hearing loss or clinical diagnosis; range of mutations including SOX10/PAX3/SNA12/SW2B/SW2C/EDN3/EDNRB/MITF, though the method of identification of these mutations was not reported in any series.24, 25, 30, 34, 37 Radiological assessment with either preoperative computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was reported in 100 patients across 10 studies (Table 1)15, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30-32, 34, 37; findings varied from normal anatomy, to malformations of the cochlea, vestibule or semicircular canals. Only one study discussed pre-implantation radiological findings in relation to genetic analysis, highlighting one case of bilateral cochlear hypoplasia in a patient with SOX10 mutation.37

3.3 Quality of studies

The methodological quality of included studies was modest, predominantly consisting of retrospective noncontrolled case series with small numbers of patients. All studies were OCEBM grade III-IV (Table 1). In addition to the heterogeneity of study types included, there were inconsistencies in reporting of pre-implantation assessment and use of variable audiological outcomes presented within and between studies which precluded formal meta-analysis. There were also limitations in reporting of WS subtype, genetic analysis, pre-implantation radiological findings, surgical technique and rehabilitation protocols (Table 2).

| Study | Number of implants | Type of implant | Implant laterality | Approach | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daneshi et al. | 6 | Nucleus 24 (4), Nucleus 22 (1), MED-EL (combi 40+) (1) | UL (6) | Not specified | Non-reported |

| Migirov et al. | 5 | Nucleus 22 (2), Nucleus 24 (1), Clarion (1), Med-El Combi 40 (1) | UL (5) | Posterior tympanotomy (3) Suprameatal (2) |

Reimplantation-device failure (1) |

| Cullen et al. | 7 | Clarion (4), Nucleus 24 (1), Nucleus 22 (1), Med-El Combi 40 (1) | UL (7) | Not specified | Seroma (1) Reimplantation-device failure (1) |

| Pau et al. | 20 | Not specified | UL (20) | Not specified | Non-reported |

| Deka et al. | 4 | Nucleus 24 (4) | UL (4) | Posterior Tympanotomy (4) | Non-reported |

| Amirsalari et al. | 6 | Nucleus 24 (6) | UL (6) | Not specified | Non-reported |

| Kontorinis et al. | 32 | Clarion (6), Nucleus 24 (20), Nucleus 22 (3), HiRes 90 K (3) | UL (18) BL (7) |

Not specified | Reimplantation (3) |

| de Sousa Andrade et al. | 7 | CI24R (7) | UL (7) | Posterior Tympanotomy (7) | Non-reported |

| El Bakkouri et al. | 30 | Not specified | UL (30) | Not specified | Non-reported |

| Broomfield et al. | 10 | Not specified | UL (10) | Not specified | Non-reported |

| Magalhães et al. | 10 | Nucleus 24 (8), Digisonic (2) | UL (10) | Not specified | Non-reported |

| Koyama et al. | 5 | CI24RE (5) | UL (5) | Scala Tympani (5) | Non-reported |

| van Nierop et al. | 16 | CI24RE (10), CI24M (3), CI500 (1) | UL (12) BL (2) |

Not specified | Non-reported |

| Clarós et al. | 25 | Cl24R (3), Cl24RE (19), Clarion CII (3) | UL (19) BL (3) |

Posterior Tympanotomy (25) | CSF Gusher (4) |

| Polanski et al. | 3 | Contour Advance (2), HiFocus (1) | UL (3) | Not specified | Reimplantation-displaced electrode (1) |

| Fan et al. | 8 | Nucleus CI512 (8) | UL (2) BL (3) |

Posterior Tympanotomy (8) | Non-reported |

- Abbreviations: BL, bilateral; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; UL, unilateral.

3.4 Audiological outcomes

Reporting of preoperative audiological assessment was highly variable. Seven studies provided pre-implantation pure tone audiometry (PTA) and five utilized speech perception scores, six reported vague description of hearing level with one study providing no details of baseline hearing (Table 3). Where provided pre-op hearing loss was in keeping with severe to profound hearing loss.

| Study | Descriptive analysis | Pure tone audiometry | Speech perception/intelligibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daneshi et al. | Bilateral profound hearing loss (n = 3) | Unaided (average) threshold: 86.7 dB (75–95 dB) | CAP median: 0 (0–1), SIR median: 1 (0–5), PAPT/HI mean: 1.7% (0%–10%), Persian spondee word test mean: 4.1% (0%–25%) |

| Migirov et al. | Bilateral profound hearing loss (n = 5) | Unaided (average) threshold: 117 dB (106–130) Unaided voice detection level mean: 89 dB (85–105 dB) |

IT-MAIS (n = 1): 28% ESP: unattainable (1), Category 1 (1), Category 2 (1), Category 3 (1) |

| Cullen et al. | Severe to profound hearing loss (n = 7) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Pau et al. | 16 had normal intraoperative EABR. 4 reported abnormal intraoperative EABR. |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Deka et al. | Congenital deafness with limited language acquisition (n = 4) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Amirsalari et al. | WS group—profound-to-severe hearing loss (n = 6) Reference group—sensorineural hearing loss (n = 75) No significant difference in baseline characteristics |

Not reported | WS group—CAP mean: 0.33 ± 0.5, SIR mean: 0 Reference group—CAP mean: 0.49 ± 0.02, SIR mean: 0.47 ± 0.03 No significant difference in baseline speech perception (p ≥ .05) |

| Kontorinis et al. | WS group—hearing loss meeting criteria for CI (n = 25) Reference group—nonsyndromic hearing loss (n = 50) |

Not reported | Not reported |

| de Sousa Andrade et al. | WS group—documented bilateral profound hearing loss and limited acquired language (n = 7) Reference group—bilateral profound hearing loss in nonsyndromic children (n = 261) |

Not reported | Not reported |

| El Bakkouri et al. | WS group—profound prelingual SNHL (n = 30) Reference group—profound prelingual SNHL with connexin mutation (n = 85) |

WS group—Unaided (average) threshold: 110 ± 10 dB Reference group—Unaided (average) threshold: 110 ± 10 dB |

Not reported |

| Broomfield et al. | Severe to profound hearing loss (n = 10) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Magalhães et al. | Severe to profound hearing loss (n = 10) | Unaided (average) threshold: 71.1 dB (70–110 dB) (2 absent) |

Speech Perception (GASP/ESP): 0, IT-MAIS/MAIS mean: 14.7% (0–62.5), MUSS mean: 30% (0–80) |

| Koyama et al. | Four patients diagnosed with congenital hearing loss and one with progressive hearing loss | Unaided (average) threshold: 117.2 dB (105–135 dB) | Not reported |

| van Nierop et al. | Not reported. | Not reported | Not reported |

| Clarós et al. | WS group—profound hearing loss (n = 22) Reference group—profound bilateral deafness (n = 86) |

WS group—Unaided (average) threshold: 95.4 dB ± 4.2 Reference group—Not reported |

Not reported |

| Polanski et al. | Bilateral profound hearing loss (n = 3) | Not reported | Hearing and speech category: H—0 S—1 IT-MAIS/MAIS mean: 3% (2.5–5), MUSS mean: 10.8% (5–20) |

| Fan et al. | Bilateral severe deafness (n = 5) | EABR >97 dB, failed otoacoustic emissions | Not reported |

- Abbreviations: CI, Cochlear Implantation; CAP, Categories of Auditory Performance; EABR, Evoked Auditory Brainstem Response; ESP, Early Speech Perception test; GASP, Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure; IT-MAIS, Infant-Toddler Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale; MAIS, Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale; MUSS, Meaningful Use of Speech Scale; PAPT/HI, Persian Auditory Perception Test for the Hearing Impaired; SIR, Speech Intelligibility Rating; WS, Waardenburg Syndrome.

Post-implantation hearing outcomes demonstrated improvement across all studies; however, reporting of follow up duration and outcome measures was heterogenous across studies. The shortest average duration of follow up was 12 months and the longest follow up period was 15 years.

Post-implantation hearing outcomes are summarized in Table 4. A total of 22 different audiological outcome measures were used with heterogeneity in outcome measures reported between studies. There was also variability seen within studies particularly regarding pre- and post-implantation outcome measures used.

| Study | Descriptive analysis | Pure tone audiometry | Speech perception/intelligibility | Overall benefit (subjective assessment) | Average follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daneshi et al. | All attending regular school and regular implant users | Not reported | CAP median: 4.5 (4–5), SIR median: 3 (3–5), PAPT/HI mean: 61.7% (35–78), Persian spondee word test mean: 85.8% (55–100) | Improvement in audiological outcomes with CI. | 3.6 y |

| Migirov et al. | Not reported | Average threshold: 31.3 dB (22.5–42.5) Voice detection level: 25 dB (10–35 dB) |

Open Set %—Monosyllable's median: 40% (25–85), Two-syllables median: 80% (65–100), Words in sentences mean: 84% (59–100) two not tested | Improvement in audiological outcomes following CI | 4.4 y |

| Cullen et al. | Not reported | Not reported | Early Speech Perception test mean (Closed Set): 96.5% (79–100) PBK test (Open Set) mean: 66% (40–84) (1 not tested short duration of use) |

Good audiological outcomes following CI | 5.8 y |

| Pau et al. | Not reported | Not reported | WS group (7 lost to follow up) Abnormal EABR (n = 3)—Melbourne Speech Perception Category: 1 Normal EABR (n = 10)—Melbourne Speech Perception category: 7 Reference group 38 of 264 had abnormal EABR and performed poorly following CI |

Patients with normal EABR benefit from CI. Abnormal intraoperative EABR associated with poor outcomes after CI | 1 y |

| Deka et al. | Not reported | Not reported | CAP mean: 4 (3–5), SIR mean: 2.75 (2–3), MAIS mean: 24.75 (18–30) | Improvement in audiological outcomes with CI. | 1 y |

| Amirsalari et al. | Not reported | Not reported | WS group (n = 6) CAP mean: 4.00 ± 1.26, SIR mean: 2.67 ± 1.03 Reference Group (n = 75) CAP mean: 5.13 ± 1.13, SIR mean: 3.79 ± 1.11 - Both groups improved SIR/CAP (p < .05), SIR significantly higher in reference group (p = .02). Age did not influence outcomes (p > .05) |

Improvement in audiological outcomes with CI. Age at implantation not significant factor in outcome | 1 y |

| Kontorinis et al. | Not reported | Not reported | HSM score mean (n = 18): 75.3% (22.6–99), FMT score mean (n = 18): 67.8% (14–95), CAP score mean (n = 5): 3.2 (min:2, max:4) - No significant difference between WS and control (p = .56) |

Good outcomes following CI. Comparable to other CI indications | 8.3 y |

| de Sousa Andrade et al. | All employ oral language as sole communication | Not reported | WS group (n = 7) Open Set-Monosyllables mean: 60.22% ± 16.5, Numbers mean: 91.66% ± 5.77, Words in sentences mean: 47.75% ± 16.7, Vowels mean: 100%. (3 not tested due to age), CAP mean: 5.63 ± 0.74, SIR mean: 3.88 ± 1.12, MAIS mean: 37.4 ± 3.97, MUSS mean: 33.20 ± 9.55 Reference group (n = 261) Open Set-Monosyllables mean: 63.6% ± 19.19, Numbers mean: 86.5% ± 20.81, Words in sentences mean: 57.8% ± 32.8, Vowels mean: 97.6% ± 10.87 CAP mean: 5.74 ± 1.24, SIR mean: 3.98 ± 1.23, MAIS mean: 36.46 ± 5.91, MUSS mean: 32.23 ± 9.95 - No difference in outcomes between WS and control (p > .05) |

Good audiological outcomes following CI. Comparable with other CI indications | 4.8 y |

| El Bakkouri et al. | Not reported | Not reported | WS group (n = 30) Closed Set Words mean: 46%, Open Set Words mean: 78% ± 26.3% Speech production level 4 or 5 (n = 27): 66% Reference group (n = 85) Closed Set Words mean: 55%, Open Set Words mean: 75% ± 25.5% Speech production level 4 or 5 (n = 60): 58% - No difference in outcomes between WS and control (p > .05) |

Good audiological outcomes following CI. No significant difference in outcomes compared to control group. | 7.1 y |

| Broomfield et al. | Communication: speech (5), speech/sign (4), pictures (1). Attend regular school (7) | Not reported | BKB score mean (n = 7): 69.4% (42–94) Speech Reception Score: 6 (n = 4), 5 (n = 5), non-user (n = 1) |

Good audiological outcomes following CI. One non-user with severe autism | 11.8 y |

| Magalhães et al. | Not reported | Average threshold: 41.1 dB (20–110 dB) | Speech Perception (GASP/ESP): 6 (n = 2), 5 (n = 1), 4 (n = 1), 2 (n = 1), 1 (n = 3), 0 (n = 1) Closed Set Word (n = 1): 80%, IT-MAIS/MAIS mean (n = 9): 63.6% (17.5–100), MUSS mean (n = 9): 65% (2.5–100) |

Improvement in audiological outcomes in effective users of CI. Early rehabilitation & family involvement key | 4 y |

| Koyama et al. | Not reported | Average threshold: 29.5 dB (23.8–35 dB) | CI-2004 three words test average score: 78% (70–92) 67-s monosyllable words test average score: 87% (80–100) - MAIS/MUSS scores all improved post operatively |

Improvement in audiological outcomes with CI. | 2 y |

| van Nierop et al. | Five children attending mainstream education | Not reported | WS group: (n = 14) RDLS LQ mean: 0.74 ± 0.21, Phoneme score mean: 80% ± 23 Reference group: (n = 48) RDLS LQ mean 0.87 ± 0.15, Phoneme score mean: 86% ± (10) |

Good audiological outcomes following CI. Comparable to reference group however additional disability may negatively impact outcomes | 8.32 y |

| Clarós et al. | Not reported | WS group Average threshold: 23.2 ± 9.9 Reference group Average threshold 21.51 - No difference in PTA between groups post CI (p = .49) |

WS group (n = 22) CAP mean: 5.8 ± 0.7, SIR mean: 4.7 ± 0.5, MAIS/IT-MAIS mean: 34.8 ± 1.7, MUSS mean: 35.6 ± 3.5 Reference group ( = 86) CAP mean: 6.2, SIR mean: 4.3, MAIS/IT-MAIS mean: 35.0, MUSS mean: 30.4. - WS group, better SIR and MUSS scores post CI (p < .05), reference group better CAP score (p < .05). No difference in IT-MAIS (p = .75) |

Improvement in audiological outcomes with CI. | 15 y |

| Polanski et al. | Not reported | Not reported | Hearing & Speech Category: H—6(2), 5(1), S–5(2) 3(1) IT-MAIS/MAIS mean: 90% (70–100), MUSS mean: 66.3% (54–85) (one case 12 months follow up) |

Improved audiological and speech outcomes post CI | 5 y |

| Fan et al. | Not reported | Not reported | IT-MAIS mean 2 years (n = 4): 83.5% (75–90), IT-MAIS 6 months (n = 1): 19%, MUSS mean 2 years (n = 4): 64.3% (57–70), MUSS 6 months (n = 1): 17% (1 child only 6 months follow up) | Improved audiological outcomes post CI. Worse than normal hearing children | 2 y |

- Abbreviations: BKB, Bamford-Kowal-Bench; CI, Cochlear Implantation; CAP, Categories of Auditory Performance; EABR, Evoked Auditory Brainstem Response; ESP, Early Speech Perception test; FMT, Freiburg Monosyllabic Test; GASP, Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure; HSM, Hochmair-Schulz-Moser sentence test; IT-MAIS, Infant-Toddler Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale; MAIS, Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale; MUSS, Meaningful Use of Speech Scale; PAPT/HI, Persian Auditory Perception Test for the Hearing Impaired; PBK, Phonetically Balanced Kindergarten test; RDLS-LQ, Reynell Developmental Language Scales Language Quotient; SIR, Speech Intelligibility Rating; WS, Waardenburg Syndrome.

PTA was reported both pre- and post-implantation in four studies24, 26, 28, 34 all of which demonstrated improvement in average thresholds across their respective cohorts. Claros et al. demonstrated an improvement in average thresholds from 95.4 dB ± 4.2 to 23.2 ± 9.9 post-CI with no significant difference in post-implantation thresholds when compared to a reference group of 86 nonsyndromic children (p = .49).24

Speech perception was assessed in all studies through varied tools. The Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale (MAIS) or the Infant-Toddler Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale (IT-MAIS) was used most frequently across six studies to assess postoperative speech perception.24, 26, 30, 32, 37, 38 Polanski et al., reported both pre and post intervention IT-MAIS/MAIS demonstrating improvement from average scores of 3%–90%. Categories of Auditory Performance (CAP) were also commonly used to assess postoperative performance in six studies,24, 27, 29-32 with two also utilizing CAP preoperatively.27, 29 Amilsari et al. demonstrated statistically significant improvement in CAP scores post-CI in 6 WS children (0.33 ± 0.5 to 4.00 ± 1.26 (p < .05)) with no significant difference in outcome when compared to a reference group of 75 implanted nonsyndromic children.29 Other assessment tools included speech recognition scores (SRS), phoneme scores, Open-Set Words (OSW), Closed-Set Words (CSW), CI-2004 test and the Melbourne Speech Perception Score.

Speech intelligibility was assessed in 10 studies through a variety of measures. The Speech Intelligibility Rating (SIR) was utilized in five studies24, 27, 29, 30, 32 and the Meaningful Use of Speech Scale (MUSS) was implemented in six to assess post-implantation speech intelligibility.24, 26, 30, 34, 37, 38 Claros et al., demonstrated significantly better speech intelligibility outcomes (SIR/MUSS) following CI compared to a reference group of 86 implanted non syndromic hearing loss cases (p < .05).24 No study used a formal framework to evaluate quality of life following CI, although four studies provided descriptive analysis through main method of communication and attendance of mainstream education.25, 27, 30, 35

Overall, outcomes were favorable following cochlear implantation regardless of assessment method used. However, follow-up post implantation was variable, as were the assessment tools used to report audiological outcomes. Pre-implantation hearing status audiology was not routinely reported and in many cases measures did not correlate with those used post-CI limiting comparison. A number of studies also provided comparison with reference groups however, these groups were often much larger, limited baseline data and not matched to the study population.

3.5 Surgical outcomes

Five studies reported on intra- or post-operative complications.15, 24, 28, 31, 38 A total of 12 complications were reported in as many patients. The most frequently reported were implant failure and CSF gusher accounting for four cases each. In patients with CSF gusher inner ear abnormalities were identified including two cases of enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA), one common cavity deformity (CCD) and one incomplete partition type II (IP-2) deformity. The EVA and IP-II were related to WS type 2, and CCD to WS type 4. Other less frequent complications included displaced electrode, seroma formation and wound infection (Table 2).

4 DISCUSSION

This systematic review and narrative synthesis reports on outcomes of cochlear implantation in profoundly deafened children diagnosed with WS. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first systematic review on this topic.

There were good audiological outcomes found across all studies, with the majority of patients reporting benefit from cochlear implantation. A wide range of assessment tools were used with few studies having comparable pre- and post-operative assessment tools. Where comparable measures were used improvement in CAP and MAIS score demonstrated improvement from baseline assessment for speech recognition.26, 27, 29 Similarly, where SIR or MUSS scores were reported pre- and post-implantation, studies demonstrated improved functionality following cochlear implantation.26, 27, 29 Whilst the majority of studies assessed either pure-tone audiometry or speech perception postoperatively, all studies that assessed speech intelligibility showed improvement in the linguistic ability following CI.24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34

Five studies also compared WS outcomes to reference groups of other causes of hearing loss undergoing CI.24, 25, 29, 30, 36 Amirsalari et al., highlighted significantly better SIR scores in reference group but no difference in CAP post CI.29 Conversely, Claros et al., identified that WS patients had better SIR but worse CAP scores. Two studies highlighted no significant difference in speech intelligibility or speech perception scores between WS and reference groups post-CI.30, 36 As such it appears that CI outcomes in WS patients are comparable to other indications for CI however, often little to no data on baseline characteristics of reference groups were provided and in all studies number of cases in reference populations vastly outnumbered the study group.

Studies highlighted several factors which may be associated with poorer outcomes following CI. These included delayed implantation, concomitant cognitive impairment and poor engagement with rehabilitation. Claros et al., discussed the importance of early implantation demonstrating benefit from CI in their population of children with WS implanted before the age of three.24 The rationale for early implantation is based on there being a period of maximal neural plasticity in the auditory pathways which ends at around age 3.5.39, 40 This was supported by Magalhaes et al., who found that in their cohort children who had later implantation after the age of three had worse hearing and speech outcomes following CI, these children also had later initial fitting of hearing aids and aural rehabilitation.26 Conversely, Amirsalari et al., found that age at implantation had no significant effect on hearing and speech outcomes however, this may influenced by their small study population.29 Van Nierop et al., found that early implantation alone was not sufficient as the presence of cognitive and physical impairments in their early implanted cohort also resulted in poorer post-CI hearing outcomes.25 Family engagement in rehabilitation was also an important factor in hearing and speech outcomes post-CI. Magalhaes et al., identified that children with lower levels of family engagement in the rehabilitation process and poor acceptance of the device tended toward poorer speech outcomes even in the presence of improved speech perception.26

The effect of WS subtype on audiological outcomes post-CI was not established, with only 12 studies detailing a broad spectrum of subtypes through clinical or genetic assessment of patients.24, 25, 27, 28, 30-32, 34 No negative impact on audiological outcomes was demonstrated following cochlear implantation regardless of the responsible mutation. Sub-analysis of audiological outcomes with varying genetic mutations was only possible in five patients given the heterogeneity of audiological measures; there was no difference between the two gene mutations, PAX3 and MITF, and post-implantation linguistic ability,25, 30 but such a small sample size can only demonstrate huge effect sizes.

The majority of WS patients who underwent either CT or MRI were found to have normal imaging and demonstrated functional improvement following CI.27, 28, 31, 32, 34 Moreover, those with IP-2, EVA, malformation of semicircular canals, vestibule or cochlea preoperatively did not exhibit a detrimental impact on audiological outcomes.15, 24, 25, 30, 31, 37 Although radiological findings had no reported impact on hearing and speech outcomes studies provided limited data on type and detail of imaging as well as reported outcome variables. It is important to note that all intraoperative gusher leaks occurred in patients with imaging demonstrating IP-2, EVA or common cavity deformity highlighting potential increased risk of complication in these patients.24

4.1 Limitations and recommendations

This is an uncommon condition and as such studies present small sample sizes and varied outcome measures limits pooled analysis. These issues could be addressed by large-scale mandatory registries of implantation recipients and results, particularly useful for such types of rare diseases. Such registries are not yet in use but the proliferation of electronic patient records and increased interest in outcome measures is likely to drive adoption. While a number of challenges exist in the implementation of national registries, including oversight, funding and legal implications, there are trends toward the development of such a database for cochlear implantation.40, 41

Additionally, the inclusion of studies presenting a diverse spectrum of audiological outcomes, many without reported pre-implantation audiological assessment, resulted in heterogeneity. Moreover, the categorical scales used for measurement of performance outcome following CI are subjective, being dependent on the assessing clinician's judgment. The audiological tools have been developed for assessment of individuals with hearing loss and therefore comparison to normative population outcomes is not possible. The use of standardized auditory and spoken language assessment tools, in addition to audiology, would allow clinicians the ability to critically assess outcomes following cochlear implantation as well as facilitate the synthesis of a wider pool of data and provide opportunities to more accurately assess outcomes on a larger scale.

Furthermore, assessment of appropriate diagnosis, either by genetic analysis or clinical classification, was difficult to ascertain in the included studies. For the five studies including genetic analysis to aid or support diagnosis of WS, it was evident that not all genetic mutations had been tested for in each patient. In the future, it would be useful if genetic testing and appropriate counseling could be undertaken whenever possible, with a variety of gene loci mutations being assessed regardless of the phenotypical clinical classification of the disease.

5 CONCLUSION

CI in congenitally deafened children with WS is a well-established intervention as a method of auditory rehabilitation. However, due to the uncommon nature of the condition, there is a lack of large-scale high-quality studies examining the use of CI in this patient group. Importantly children with WS are at risk of temporal bone abnormalities which may complicated CI and as such imaging is vital for prior to intervention for surgical planning. Overall, outcomes following CI are good with most patients demonstrating improved audiometry, speech perception and speech intelligibility. Outcomes are also comparable to those of other cohorts of congenitally deafened children. Although further high-quality studies are required, the existing evidence base supports the use of cochlear implantation in appropriately selected cases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With thanks to Matthew Stone, Clinical Effectiveness Librarian at University Hospitals of North Midlands.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.