The Social Network of Otolaryngology: Collaborative Publishing Relationships by Gender

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Niketna Vivek and Evan Clark contributed equally to this manuscript.

ABSTRACT

Objective

This study aims to evaluate if gender differences exist in social connectedness (betweenness centrality) and professional impact (h-indices) within Otolaryngology when controlling for variables such as academic rank, subspecialty, and geographic region.

Methods

Physician faculty (n = 2494) from 129 US ACGME accredited otolaryngology programs were identified. Characteristics included gender, academic rank, sub-specialty, and SCOPUS IDs. The co-authorship network was visualized and consisted of 2265 physicians (nodes) connected by 28,408 collaborative relationships (edges). The professional connectedness of physicians was calculated using betweenness centrality (BWC), which quantifies how frequently a physician node appears on the shortest path between two other nodes. Analysis employed ordinal regression fitting semiparametric multivariable cumulative probability models.

Results

Among 2265 faculty physicians identified, 69% were male, 26% were female, and 5% were unknown. Female faculty had lower h-index and BWC scores compared to their male colleagues. When controlling for subspecialty and region, male and female assistant professors did not show evidence of a difference in BWC scores (odds ratio (OR) = 0.96, p = 0.80). However, among associate and full professors, males tended to have higher BWC compared to female counterparts (OR = 1.47, p = 0.0086 for associate and OR = 2.05, p < 0.0001 for full professors).

Conclusion

Analysis of our co-authorship network showed that current male and female Otolaryngology faculty have equivalent academic impact and professional connectedness at lower academic ranks but diverge at higher ranks. These findings suggest that increased efforts to support female academic development at the mid-career level may reduce the observed gender disparities at higher academic ranks.

Level of Evidence

N/A.

1 Introduction

Gender disparity among academic physicians is well-documented, with numerous studies highlighting the discrepancies in academic impact and promotion [1, 2]. Women have lower h-index scores and tend to be underrepresented at higher academic ranks in surgical specialties [3-5]. In Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (OHNS) in 2020, women represented 36% of full-time academic faculty yet held less than 5% of department chair positions [6]. McCrary et al. found that after completing an Advanced Head & Neck Surgical Oncology fellowship, females initially demonstrated high levels of academic productivity but then had lower h-indices than their male colleagues during later stages in their career [7]. Miller et al. found that while a proportional number of women who completed head & neck fellowship entered academic practice, females were less likely to hold full professor roles than their male counterparts [8, 9].

While many studies highlight the gender disparity that exists in the field of otolaryngology, the cause of these gender differences and when they occur along career trajectories remain unclear. Metrics including h-index, academic rank, and fellowship training have been used to elucidate factors contributing to gender disparities in otolaryngology. One newer method that has the potential to provide insight into gender differences in academic impact and ranking is social network analysis of co-authorship networks [10].

By examining trends in academic OHNS faculty, we seek to identify barriers to gender equity and propose strategies to increase representation of women in academic leadership roles. These results can guide programmatic efforts in female academic career development aimed at reducing gender disparities in OHNS.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Collection and Processing

Physician faculty (n = 2494) from all US ACGME accredited otolaryngology residency programs (n = 129) were identified using brute force web search in January 2024. Information collected included: physician name, gender, academic title, degrees obtained, primary institutional affiliation, region of practice, and subspecialty within otolaryngology based on board certification. Subspecialties included facial plastics, general, head & neck, laryngology, neurotology, pediatrics, and rhinology. Several subspecialties fell outside these classifications including sleep, allergy, oral and maxillofacial, academic researchers, and otherwise unknown, and were excluded from further downstream analysis.

A Python script was used to identify the Scopus IDs for these physicians using their name, affiliations, and ORCID identifiers. Academic impact was quantified using h-indices, a metric using the number of publications and citations to describe a researcher's scientific productivity and impact. H-indices were queried using the Elsevier Author Lookup API. Titles, coauthors, and identifiers (DOI, PMID, and publication Scopus ID) for all publications were queried using the Elsevier Scopus Search API. Total publications (n = 25,095) were filtered to only include those containing at least two identified physicians, resulting in a total of 24,095 publications co-authored through 88,245 collaborations by 2265 identified physicians.

2.2 Network Map Visualization and Analysis

Network maps of the co-authorship network were generated and analyzed using statistical packages in Gephi (Gephi 0.10.1) and custom R scripts (R Core Team, 2023, Version 4.3.3). The centrality measures of degree and betweenness were explored. Degree centrality measures the number of adjacent connections a node has. Betweenness centrality measures how often a node appears on the shortest path between two other nodes. Odds ratios (OR) were used to analyze the difference in likelihood that a male or female faculty member would have a higher BWC or h-index compared to other members of the group. Further explanation of OR in context can be found in Figure S1.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Due to the skewness in the distribution of BWC and h-index, semiparametric multivariable cumulative probability models (CPM) were fit to study their association with gender while adjusting for academic rank and subspecialty [11]. CPM analyses were conducted using the Regression Modeling Strategies (rms, Version 6.8–1) package in R. The interaction terms between gender, academic rank, and subspecialty were included in these models. The estimated OR of higher BWC or h-index with a 95% confidence interval between groups was reported from the regression model. Data, Python, and R scripts availability information is located in the Data Sharing Statement Supplement.

3 Results

3.1 Gender Differences Based on Academic Rank, Subspecialty, and Region

Of academic otolaryngologists included, 25.9% (n = 586) were female, 68.6% (n = 1553) were male, and 5.6% (n = 126) were missing gender information. Comparisons between male and female physicians regarding their regions, specialties, and academic positions are shown in Table 1. Women tended to have lower median h-index than their male counterparts (p < 0.001). Similarly, women also tended to have lower BWC scores.

| Gender | p b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, N = 586a | Male, N = 1553a | ||

| Region | 0.003 | ||

| Midwest | 141 (28.1%) | 360 (71.9%) | |

| Northeast | 144 (22.3%) | 502 (77.7%) | |

| Puerto Rico | 3 (20.0%) | 12 (80.0%) | |

| South | 167 (28.7%) | 414 (71.3%) | |

| West | 131 (33.1%) | 265 (66.9%) | |

| Specialty | < 0.001 | ||

| Facial Plastics | 47 (21.6%) | 171 (78.4%) | |

| General | 76 (21.9%) | 271 (78.1%) | |

| Head & Neck | 100 (23.4%) | 327 (76.6%) | |

| Laryngology | 59 (36.4%) | 103 (63.6%) | |

| Neurotology | 55 (21.7%) | 198 (78.3%) | |

| Pediatric | 156 (39.2%) | 242 (60.8%) | |

| Rhinology | 44 (23.7%) | 142 (76.3%) | |

| Unknown | 49 (33.1%) | 99 (66.9%) | |

| Academic title | < 0.001 | ||

| Assis. Prof. | 266 (36.6%) | 461 (63.4%) | |

| Asso. Prof. | 134 (25.4%) | 393 (74.6%) | |

| Prof. | 76 (15.3%) | 421 (84.7%) | |

| Unknown | 110 (28.4%) | 278 (71.6%) | |

| H-index | 7 (4, 13) | 11 (5, 20) | < 0.001 |

| Betweenness centrality (BWC) | 384 (33, 1676) | 817 (72, 3311) | < 0.001 |

- a Median (IQR) or Frequency (row %).

- b Pearson's Chi-squared test; Wilcoxon rank sum test.

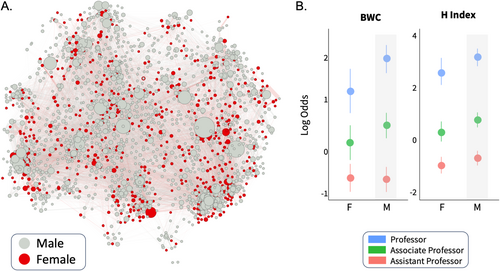

The constructed co-authorship network contained 2265 nodes (physicians) and 28,408 edges (collaborative relationships) from the 24,095 publications satisfying inclusion criteria. The network plotted with color and size gradients representing gender and BWC respectively is shown in Figure 1A.

3.2 Regression Analysis Reveals the Emergence of Disparities at Higher Academic Rank

To investigate whether the differences in h-index and BWC between males and females were due to differences in subspecialty and academic rank, multivariable regression analyses (CPM models due to skewness of the data) was performed. We first fit a model for BWC on gender, academic rank, and the interaction between them. We found that the BWC difference between gender groups depended on academic rank (p interaction = 0.01). The OR (for higher BWC) of male to female was estimated to be 0.96, p = 0.80, among assistant professors, but was 1.47, p = 0.0086, and 2.05, p < 0.0001, among associate professors and professors, respectively (Figure 1B, Table 2). These findings indicate that female and male assistant professors may have similar BWC; however, female associate and full professors have lower BWC than male counterparts. Results from a model for h-index paralleled the BWC findings. (OR of male to female: Assistant Professor 1.31: p = 0.0605, Associate Professor 1.57: p = 0.0023, Professor 1.72: p = 0.0018).

| Academic title | Male—Log odds | Female—Log odds | Odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWC | Professor | 1.99 | 1.28 | 2.05 |

| Asso. Professor | 0.50 | 0.12 | 1.47 | |

| Assis. Professor | −0.71 | −0.68 | 0.96 | |

| H Index | Professor | 3.20 | 2.66 | 1.72 |

| Asso. Professor | 0.79 | 0.34 | 1.57 | |

| Assis. Professor | −0.69 | −0.96 | 1.31 |

We next added subspecialty to the regression models with both two-way and 3-way interactions between gender, academic rank, and subspecialty. While OR differed across all subspecialties, disparities in BWC and h-index were more evident in certain fields. These differences were most pronounced in Neurotology, Pediatric Otolaryngology, and Head & Neck Surgery, particularly at the full professor level (Table 3, Figure S1).

| Betweenness centrality | H-Index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | Academic title | Male—Log odds | Female—Log odds | Odds ratio | Male—Log odds | Female—Log odds | Odds ratio |

| Facial Plastics | Prof. | 1.12 | 0.08 | 2.83 | 1.91 | 1.00 | 2.48 |

| Asso. Prof. | −0.66 | −0.34 | 0.73 | 0.19 | −0.63 | 2.27 | |

| Assis. Prof. | −1.66 | −1.21 | 0.64 | −1.70 | −1.76 | 1.07 | |

| General | Prof. | 1.58 | 1.73 | 0.86 | 2.66 | 3.12 | 0.63 |

| Asso. Prof. | −1.40 | −2.00 | 1.83 | −1.15 | −0.56 | 0.55 | |

| Assis. Prof. | −2.29 | −2.39 | 1.10 | −2.45 | −2.80 | 1.42 | |

| Head & neck | Prof. | 1.78 | 1.11 | 1.95 | 3.16 | 2.42 | 2.11 |

| Asso. Prof. | 0.62 | −0.11 | 2.06 | 0.77 | −0.04 | 2.25 | |

| Assis. Prof. | −0.52 | −0.68 | 1.18 | −0.43 | −1.09 | 1.94 | |

| Laryngology | Prof. | 1.59 | 1.30 | 1.33 | 2.28 | 2.78 | 0.61 |

| Asso. Prof. | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.77 | −0.17 | 0.35 | 0.59 | |

| Assis. Prof. | −0.78 | −0.64 | 0.87 | −1.39 | −1.91 | 1.68 | |

| Neurotology | Prof. | 1.55 | −0.06 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 2.24 | 2.14 |

| Asso. Prof. | 0.22 | 0.14 | 1.08 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 1.09 | |

| Assis. Prof. | −0.80 | −0.99 | 1.20 | −0.65 | −1.32 | 1.96 | |

| Pediatric | Prof. | 1.77 | 0.76 | 2.76 | 2.32 | 1.98 | 1.40 |

| Asso. Prof. | 0.59 | −0.48 | 2.91 | 0.23 | −0.84 | 2.92 | |

| Assis. Prof. | −1.08 | −0.98 | 0.91 | −1.49 | −1.47 | 0.99 | |

| Rhinology | Prof. | 2.48 | 2.84 | 0.70 | 3.75 | 2.46 | 3.66 |

| Asso. Prof. | 1.01 | 0.81 | 1.22 | 1.12 | −0.10 | 3.38 | |

| Assis. Prof. | −0.34 | −0.24 | 0.90 | −0.47 | −0.38 | 0.91 | |

4 Discussion

Our study investigated gender disparities in scholarly impact and professional connectedness among academic otolaryngologists. Our results demonstrated that male and female Otolaryngology faculty have equivalent academic impact and professional connectedness at lower academic rank. However, among current associate and full professors, males tended to have higher BWC and h-indices compared to female counterparts.

Recent analysis of gender composition of residents and faculty in OHNS residency programs in the United States demonstrated that women accounted for 42%, 30%, 27%, and 8% of current residents, residency program directors, faculty, and department chairs, respectively. The underrepresentation of women in higher academic ranks persists despite efforts to promote gender diversity and inclusivity in academic medicine. The importance of female mentorship and role models in the recruitment, retention, and promotion of women in medicine has been well demonstrated in multiple academic specialties including OHNS [6, 12-14]. Our results raise the possibility that these mentorship programs may succeed at reducing gender disparities when they increase the social connectedness of junior faculty in established professional networks.

Our findings are consistent with prior literature documenting gender disparities in academic medicine, particularly in authorship networks and scholarly productivity. Warner et al. [10] found that female faculty had significantly less reach within co-author networks, which correlated with slower promotion rates and higher attrition, even after adjusting for publication count and specialty. Similarly, Li et al. [1] demonstrated in a meta-analysis that women are consistently underrepresented at higher academic ranks across multiple specialties, often with lower h-indices than their male counterparts. Meta-regression by data collection year did demonstrate improvement with time. Our results in otolaryngology mirror these trends within literature, showing that gender disparities in both professional connectedness (BWC) and scholarly impact (h-index) become more apparent at the associate and full professor levels.

Compared to prior studies, our methodology adds granularity by using semiparametric cumulative probability models, which allowed us to account for skewed distributions in BWC and h-index while including interaction terms across gender, academic rank, and subspecialty. This approach not only confirmed previously observed disparities, but also identified which subspecialties showed the most pronounced gender differences. While earlier studies have focused on binary comparisons of gender or basic network metrics, our stratified regression analysis provides deeper insight into where these disparities emerge, offering clearer targets for mid-career interventions.

There are limitations to our study. First, the cross-sectional design prevents an analysis of trends over time and limits conclusions on causation. Second, while we observed disparities at higher academic ranks, these may partially reflect historical demographic trends—such as the lower proportion of women in academic otolaryngology several decades ago—which could have influenced early-career networking opportunities among current senior faculty. Additionally, this work focuses on gender without considering the impact of other personal identities such as race and ethnicity. Finally, this data was abstracted from program websites and assessed using personal pronouns and photographs and does not conform to the gold standard of self-identified gender.

Gender disparities in academic medicine impact patient care and health policy by influencing the diversity of perspectives and expertise within the field. Addressing gender inequities in academic surgery requires multifaceted approaches, necessitating targeted interventions to support career development coupled with institutional commitment to promote gender parity. Our work underscores the need to utilize these policies during the mid-career stage to accelerate gender equity within the field.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.