Association of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo with Depression and Anxiety—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Brian Sheng Yep Yeo and Emma Min Shuen Toh contributed equally to this study.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the extent to which Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) is associated with a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients.

Data Sources

Three databases including PubMed, Embase, and The Cochrane Library were searched by two independent authors from inception to June 12, 2022 for observational studies and randomized controlled trials investigating the association between BPPV and depression and anxiety. We included studies published as full-length articles in peer-reviewed journals with an adult population aged at least 18 years who have BPPV, detected through validated clinical methods like clinical diagnosis, interview and Dix-Hallpike test.

Results

A total of 23 articles met the final inclusion criteria and 19 articles were included in the meta-analysis. BPPV was associated with a 3.19 increased risk of anxiety compared to controls, and 27% (17%–39%) of BPPV patients suffered from anxiety. Furthermore, the weighted average Beck's Anxiety Inventory score was 18.38 (12.57; 24.18), while the weighted average State–Trait Anxiety Index score was 43.08 (37.57; 48.60).

Conclusion

There appears to be some association between BPPV and anxiety, but further studies are required to confirm these associations. Laryngoscope, 134:526–534, 2024

INTRODUCTION

Dizziness is a debilitating symptom experienced by 20%–30% in the population,1 especially those with vertigo.2 Among the types of vertigo, people with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) display high levels of disability and suffer from lower quality of life.3-5 BPPV is a condition where patients have episodes of vertigo with sudden changes in head position,6 because otoconia particles have been displaced from the otolithic membrane in the inner ear.7 Well-known symptoms of BPPV include impaired balance, tiredness, slower walking speed, greater number of falls,8 and motion intolerance.9 However, an issue that remains unaddressed is the association of anxiety and depression with this condition. Abrupt episodes of dizziness caused by BPPV may lead to patients feeling anxious because of its paroxysmal nature.10

Clinical studies have been conducted to evaluate the association between vestibular disorders and psychiatric disorders. It was found that BPPV patients had a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders.11-13 One study indicated that BPPV patients suffered from moderate anxiety,14 while another showed that it was mild anxiety.15 Current standards of clinical care for BPPV mainly revolve around vestibular rehabilitation such as particle repositioning manoeuvres, or surgical interventions,16 with minimal focus on treating the mental health of patients. Thus, it is important that the degree of correlation be established to determine if BPPV patients are at risk for anxiety and depression, for pre-emptive intervention or potential treatment.

The available systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the association of anxiety and depression with BPPV are limited in quantity and suffer from the limitations of confounding variables. Given the importance of mental health in today's context, a comprehensive review of existing literature is timely and important. Hence, we performed this systematic review and meta-analysis to provide clinicians with a clearer picture of the impact of BPPV on patients' mental health. It is our hypothesis that BPPV patients are more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression respectively.

METHODS

This review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022358102). The systematic review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Search Strategy

Two authors (BSYY, EMST) searched three databases, PubMed, Embase, and The Cochrane Library for articles relating to the associated of anxiety and depression with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo of from inception to June 12, 2022.17 The PRISMA checklist is included in Table S1. The general search terms included the use of “Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo”, “depression” and “anxiety”. The full search strategy is included in Table S2.

Study Selection

We included randomized controlled trials and observational studies published as full-length articles in peer-reviewed journals that included adults at least 18 years old who have clinically diagnosed BPPV. We compared these patients with healthy individuals without peripheral vertigo. The main outcomes were either anxiety or depression diagnosed based on acceptable clinical diagnostic criteria (e.g. Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder [DSM] criteria), or measurement of depression or anxiety via commonly used test scores such as Beck's Depression Inventory. We excluded systematic reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, case reports, letters, conference proceedings, paediatric studies and studies published in any language other than English. Titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies, followed by their full texts were independently screened by two authors (BSYY, EMST) to check the eligibility for inclusion, with disputes resolved through the appeal and consensus from a third independent author (RYSN). Article screening was performed on the online platform Rayyan—Intelligent Systematic Review.18

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias of included studies was assessed by reviewers (BSYY, NEL, RSL) using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies or the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias (RoB) tool for randomized controlled trials, with disagreements resolved by consensus or appeal to another author (EMST).19, 20 The NOS is a 9-point scale based on an 8-item checklist that consists of three domains: selection, comparability, and outcome. For each item in the checklist assessed, studies selected that were indicative of low risk of bias were awarded a star. Studies scoring 7–9 points, 4–6 points and 3 or fewer points were at low, moderate, and high risk of biases, respectively. The Cochrane RoB tool used five parameters to determine low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias, including bias from randomization, bias from deviation from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of outcomes and bias in the selection of reported result. The overall risk of bias of each study will be determined subsequently. This can be found in Supplementary Table S3.

Data Extraction

Relevant data from included articles were extracted by a pair of independent authors (NEL, RSL) into a structured proforma. Extraction findings were verified by two other independent reviewers (BSYY, EMST). Study characteristics and patient data including but not limited to first author, year of publication, study design, country, sample size, mean/median age, percentage male, mean primary depression or anxiety test score used, hazard ratios of depression or anxiety among patients with BPPV and healthy controls. A summary of demographic data of included studies can be found in Table I. Further information on the extracted studies such as psychometric test score data and the definition of outcomes can be found in Tables S4 and S5.

| Demographics | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, Journal, Year | Country | Study Design | Continuous/Dichotomised | Population Type | Mean Age, Years | Gender, n | Sample Size, n | Duration of Illness, Months | Follow-Up, Months | ||||

| Mean/Median | SD | M | F | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||

| Bayat et al., Cureus, 2020 | Iran | Cross-Sectional | Continuous | BPPV | 49.88 | 15.06 | 17 | 24 | 41 | - | - | - | - |

| Best et al., Neuroscience, 2009* | Germany | Cohort (Prospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 55.64 | 13.41 | 8 | 11 | 19 | - | - | 12 | - |

| De Stefano et al, Auris Nasus Larynx, 2014 | Italy | Cross-Sectional | Dichotomous | BPPV | 72.9 | 6.14 | 685 | 407 | 1092 | - | - | - | - |

| Eckhardt-Henn et al., Journal of Neurology, 2008 | Germany | Cohort (Prospective) | Both | BPPV | 54.25 | 12.55 | 11 | 9 | 20 | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 43.43 | 16.57 | 12 | 18 | 30 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Ferrari et al., Psychosomatics, 2014 | Italy | Case–Control (Retrospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 52.47 | 11.11 | 28 | 64 | 92 | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 51.39 | 17.28 | 55 | 86 | 141 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Hagr, International Journal of Health Sciences, 2009 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-Sectional | Continuous | BPPV | 46.7 | - | 22 | 28 | 50 | - | - | - | - |

| Hong et al., Otology and Neurotology, 2013 | South Korea | Cohort (Prospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 49.2 | 2.4 | 47 | 147 | 194 | - | - | - | - |

| Kahraman et al., Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 2017 | Turkey | Cohort (Prospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 52/52 | 14.15 | 12 | 20 | 32 | - | - | 0.46 | - |

| Control | 52.94/55 | 15.33 | 14 | 18 | 32 | - | - | 0.46 | - | ||||

| Kozak et al., Arch Neuropsychiatry, 2018 | Turkey | Cross-Sectional | Dichotomized | BPPV | 38.97 | 10.31 | 7 | 39 | 46 | 0.36†; 0.39‡ | 0.42†; 0.44‡ | - | - |

| Control | 41.32 | 11.73 | 9 | 65 | 74 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Lahmann et al., Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 2015 | Germany | Cross-Sectional | Dichotomized | BPPV | - | - | - | - | 87 | - | - | - | - |

| Molnar et al., European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 2022 | Hungary | Cross-Sectional | Continuous | BPPV | - | - | - | - | 47 | 93.2 | 76 | - | - |

| Monzani et al., Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 2001 | Italy | Cross-Sectional | Continuous | BPPV | - | - | 14 | 28 | 42 | 24.3 | - | - | - |

| Control | 52.8 | - | 24 | 62 | 86 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Muñoz et al., BMC Family Practice, 2019 | Spain | Cross-Sectional | Dichotomized | BPPV | 52 | - | 32 | 102 | 134 | - | - | - | - |

| Obermann et al., Journal of Neurology, 2015 | Germany | Cohort (Prospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 64.9 | 13 | 52 | 131 | 183 | 48 | 68.4 | 24 | - |

| Ozdilek et al., The Journal of International Advanced Otology, 2019 | Turkey | Case–Control (Prospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 40.5 | 13.3 | 17 | 43 | 60 | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 38.2 | 11.4 | 31 | 29 | 60 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Pollak et al., American Journal of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Medicine and Surgery, 2017 | Israel | Cohort (Prospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 59.2 | 14.5 | 14 | 23 | 37 | - | - | 2–3 | - |

| Vaduva et al., European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 2018* | Spain | Cohort (Retrospective) | Dichotomized | BPPV | 63.3 | 15.6 | 112 | 249 | 361 | - | - | 1 | - |

| Warninghoff et al., BMC Neurology, 2009 | Germany | Cohort (Prospective) | Both | BPPV | - | - | - | - | 19 | - | - | - | - |

| Wei et al., Frontiers in Neurology, 2018 | China | Cohort (Retrospective) | Dichotomized | BPPV | 53.9 | 13.93 | 46 | 81 | 127 | - | - | 6 | - |

| West et al., The Journal of Advanced Otology, 2019* | Denmark | Cohort (Prospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 56.9 | 14.6 | 8 | 18 | 26 | - | - | 33 | 3 |

| Yardley et al., Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 1999 | Mexico | Case–Control | Continuous | BPPV | - | - | - | - | 13 | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 39.8 | 12.2 | 14 | 26 | 40 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Yuan et al., Medicine, 2015 | China | Cross-Sectional | Continuous | BPPV | 48.9 | 10.07 | 17 | 32 | 49 | - | - | - | - |

| Zhu et al., Medicine, 2020* | China | Cohort (Prospective) | Continuous | BPPV | 50.86 | 13.47 | 43 | 88 | 131 | - | - | 3 | - |

- Abbreviation: BPPV, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

- * Systematic review only papers.

- † Patients without axis I disorder.

- ‡ Unilateral.

Statistical Analysis

For studies with continuous outcomes including depression or anxiety test scores, we pooled the standardized mean differences of depression or anxiety test scores that examine psychological function between patients with BPPV and healthy controls. For studies with dichotomous outcome measures such as depression or anxiety, we pooled adjusted odds ratios.

All analysis was conducted in R Studio (Version 4.0.3) using the meta package.21 Statistical heterogeneity was assessed via I2 and Cochran Q test values, where an I2 value of 25%, 50%, and 75% represented low, moderate, and high degree of heterogeneity respectively.22, 23 A Cochran Q test with p-value of ≤0.10 was considered significant for heterogeneity. However, random effects models were used in all analyses regardless of heterogeneity as this level of heterogeneity was expected among the studies. Statistical significance was considered for outcomes with a p value ≤0.05.

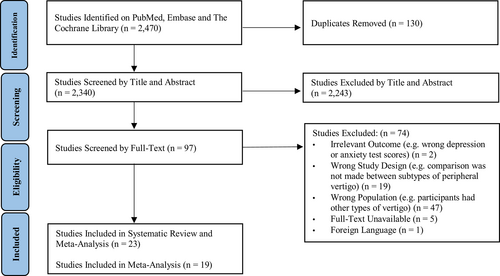

RESULTS

A total of 2470 articles were included in the initial search after removal of duplicates, of which 97 were selected for full text review. There were 23 articles that met the final inclusion criteria and 19 articles were included in the quantitative meta-analysis. (Figure 1). The systematic review included a total of 2902 BPPV patients while 2365 BPPV patients were included in the meta-analysis. Where data was available, there were 1192 male and 1544 female BPPV patients and the mean age among these patients was 62.2. Of the 23 included studies, all were observational studies, with three case–control, 11 cohort studies and nine cross-sectional studies. Fifteen studies were conducted in Europe, one study was conducted in North America and seven studies were conducted in Asia. All included studies were assessed for risk of bias with the NOS score as no randomized controlled trials satisfactory of our inclusion criteria were found (Supplementary Material 3).

Severity of Depression and Anxiety Among those with BPPV

Severity of depression according to single arm questionnaire scores

Nine papers reported depression test scores of patients with BPPV. Three papers reported using the Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI), three papers reported using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), two papers used the General Depression Scale (ADS) and Zung's Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) was utilized by one paper. The mean for depression test scores in BPPV papers were 6.35 (95% CI: 1.39–11.31), 15 (95% CI: 12.28–17.72), 4.92 (95% CI: 3.58–6.26), 33.41 (95% CI: 31.35–35.47) for papers that reported BDI, ADS, HADS and SDS respectively.

Severity of anxiety according to single arm questionnaire scores

Ten papers reported anxiety test scores of patients with BPPV, of which four papers utilized State–Trait Anxiety Index (STAI), three papers utilized Beck's Anxiety Inventory (BAI) while HADS, Zung's Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and vertigo symptom scale-AA were utilized by one paper each. The mean for anxiety test scores in BPPV papers were 43.08 (95% CI: 37.57–48.59), 18.38 (95% CI: 12.57–24.18), 8.67 (95% CI: 6.59–10.75), 34.53 (95% CI: 32.43–36.63), 2.13 (95% CI: 1.67–2.59) for papers that reported STAI, BAI, HADS, SAS, and vertigo-symptom scale-AA respectively.

Association Between BPPV with Depression and Anxiety Test Score Changes

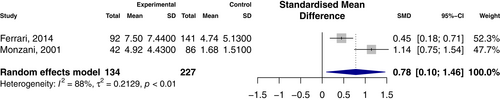

Association with depression scores

Two studies were analyzed to demonstrate the pooled standardized mean differences of depression test scores between patients with BPPV and healthy controls. Pooled analysis of 361 participants revealed a significant difference in depression test scores between BPPV and controls. (SMD: 0.780, 95% CI 0.10–1.46). (Figure 2) There was a high degree of heterogeneity between the studies of I2 = 88%.

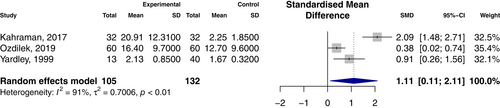

Association with anxiety scores

Three studies were analyzed to demonstrate the pooled standardized mean differences of anxiety test scores between patients with BPPV and healthy. Pooled analysis of 237 participants revealed a significant difference in anxiety test scores between BPPV and controls. (SMD: 1.11, 95% CI 0.11–2.11). (Figure 3) There was a high degree of heterogeneity between studies of I2 = 91%.

Proportion of Depression and Anxiety Among those with BPPV

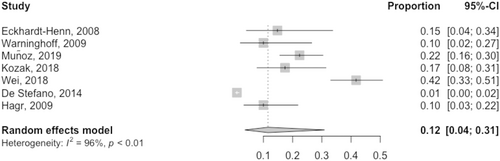

Proportion of depression according to single arm studies

Seven studies reported the prevalence of depression in BPPV patients. The pooled analysis showed that among those with BPPV, the prevalence of depression was 12% (95% CI: 4%–31%). (Figure 4) There was a high degree of heterogeneity between studies of I2 = 96%.

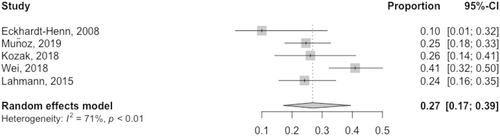

Proportion of anxiety according to single arm studies

Meanwhile, five studies reported the prevalence of anxiety in BPPV patients. The pooled analysis showed that among those with BPPV, the prevalence of anxiety was 27% (95% CI: 17%–39%). (Figure 5) There was a high degree of heterogeneity between studies of I2 = 71%.

Association Between Psychiatric Disorders and Vestibulopathies

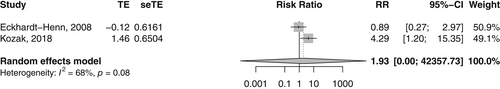

Association with risk of depression

A total of two studies conducted a double-arm analysis to compare the rate of depression in those with BPPV to a control group. There were no associations between depression and vestibulopathy observed in patients with BPPV (RR: 1.93, 95% CI: 0–42357.73). (Figure 6).

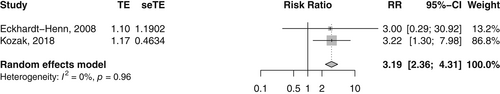

Association with risk of anxiety

Two studies included control groups to compare the rate of anxiety in those with BPPV with controls. A significant association was observed between anxiety among those with BPPV (RR: 3.19, 95% CI: 2.36–4.31). Among the subgroup of patients where anxiety was analyzed with BPPV, there was low heterogeneity (I2 = 0). (Figure 7).

Systematic Review Narrative Summary

There were four studies, while interesting and contributed to the discussion, could not be included in the overall meta-analysis due to lack of reporting of data, or discrepancies in patient selection according to definition of vertigoes or psychiatric disorders. Best et al. is a prospective longitudinal study of 68 patients investigating multiple questionnaire scores for psychological strain, finding that patients with vestibular vertigo syndromes with of psychiatric disorders had significantly more emotional distress, including anxiety and depression, across four vestibular syndromes.24 Vaduva et al. found that there was a high percentage of residual symptoms including anxiety disorders in 361 patients who had been treated for and recovered from BPPV.25 Zhu et al. compared the DHI and HADS scores of 176 patients with BPPV and vestibular migraine and found that changes in DHI scores were significantly correlated with increased in HADS scores towards anxiety and depression.26 West et al. analyzed repositioning chair treatment in refractory BPPV for 26 patients, which reported a decrease in HADS score and vertigo-associated emotional distress after treatment.27

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis comprising 23 studies and 2902 patients studied the association between BPPV and psychiatric disorders. There was a high prevalence of anxiety in patients with BPPV, where a significant association was found between BPPV and anxiety compared to healthy controls.

BPPV and Anxiety

Our study suggests that 27% of BPPV patients suffered from anxiety and BPPV was associated with a 3.19 increased risk of anxiety compared to controls. These findings of the prevalence of anxiety among patients with BPPV is similar to previously reported results.28, 29 These results are higher than literature-reviewed reported adjusted worldwide estimates, which suggest the prevalence of anxiety disorders ranges from 5.3% to 10.4% in the general population.30 In addition, while a direct comparison of scores between BPPV patients and controls would have ideally allowed for a more robust analysis, the average anxiety test scores among the papers determined in our study are indicative of anxiety. A BAI score of >7 indicates a mild anxiety disorder, > 15 indicates a moderate anxiety disorder and >25 demonstrates a severe anxiety disorder. A STAI cut-off score of 40 is normally suggestive of clinically significant symptoms which reflects a state of anxiety.31

Although the standardized mean anxiety questionnaire scores were higher among those with BPPV than controls, this relationship was only analyzed among three studies. Other evidence including the risk ratio and results from single arm studies may lend evidence to suggest that there could be a relationship between BPPV and anxiety. It had been previously suggested that patients with anxiety disorders are at a higher risk of developing BPPV,32 and these abrupt and unexpected changes in head movement for BPPV patients may trigger fear and anxiety.15

Proposed Mechanisms

While there could be associations between BPPV and anxiety, the mechanisms between peripheral vertigos and psychiatric comorbidities are complex. There have been hypotheses attempting to explain the association between vestibular disorders and psychiatric conditions – namely the otogenic and psychogenic hypotheses.33

Under the otogenic hypothesis, vertigo may lead to secondary psychological distress.34 Studies have proposed that the somatopsychic effects of vestibular dysfunction perception can precipitate anxiety. Vertiginous attacks may trigger imbalances, a feeling of environmental spiralling, spatial orientation misjudgements, nausea and vomiting. Patients with BPPV may avoid activities that precipitate dizziness to spare the potential for dizziness to cause physical harm or social embarrassment.26, 35 The unpredictable and uncontrollable nature of vertiginous attacks may exacerbate psychological distress and reduce the patient's quality of life.24, 36, 37

The psychogenic hypothesis suggests that pre-existing psychological distress can manifest as secondary vertigo or dizziness. Hyperventilation secondary to psychological distress may stimulate vestibular dysfunction by interfering with vestibular compensation mechanisms or by altering peripheral and central somatosensory input in the lower limbs.38, 39

The link between the vestibular and emotional processing systems may be explained by several postulated theories. First, neurotransmitters and neuroanatomical regions involved in the vestibular systems and emotional responses are similar.40 For instance, studies by Balaban et al. elucidated how vertigo and anxiety may be explained by an integrated network of various neural components, including afferent interoceptive information processing, a vestibulo–parabrachial nucleus network, a cerebral cortical network, a raphe nuclear–vestibular network, a coeruleo–vestibular network and a raphe–locus coeruleus loop.41, 42 Monoaminergic inputs to the vestibular system may also mediate the effects of anxiety on vestibular function.42

In addition, psychological distress may affect therapeutic outcomes in patients with BPPV. Hence, determining the prevalence of anxiety and depression among BPPV patients may contribute to identifying potential confounders to treatment efficacy, and clinicians can look out for the psychiatric comorbidities on screening.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the large number of studies included, to increase the credibility of the results. Furthermore, we included a variety of effect size measurements such as standardized mean differences, odds ratios, prevalence and weighted mean, to draw conclusions between anxiety and depression and BPPV. We included analysis of multiple questionaries for depression and anxiety, allowing us to be comprehensive in our assessment of psychiatric disorders. One of the limitations of our study is that we were not able to account for the severity of vestibular dysfunction or the chronicity of symptoms, which are known to influence the development of psychological distress,43 as the number of double arm studies with this data was limited. Future subgroup analysis could analyze patients according to severity of BPPV according to the Dizziness-Handicap Index and Vertigo Symptom Scale. Some studies were also specific to studying only patients with intractable or refractory disease, while others were unspecified, adding heterogeneity to the results. Furthermore, there were insufficient studies which included control groups to achieve meaningful dual arm comparisons or statistical significance in all components, which may have strengthened the analysis. The small number of studies also meant we could not assess publication bias in our studies, demonstrate funnel plots or perform Egger's regression tests. Additionally, we noted that there were several studies with a high risk of bias rating on NOS, limiting the credibility of our analysis. We were also not able to perform meta-regression for other confounding variables. Furthermore, we were unable to expand our scope to include all peripheral vestibulopathies and psychiatric conditions, and cannot conclude the effect of other types of vestibulopathy on psychiatric conditions. Selection bias may also be prevalent among studies which investigated the association of BPPV and anxiety. Many patients with BPPV may not seek medical attention, and anxiety may be assumed to have a higher prevalence in those who sought medical attention for the condition. Finally, given that our studies were observational in nature, and we did not include any randomized control trials, all conclusions made are correlational rather than causal.

CONCLUSION

This study adds to the growing evidence to support assessing and potentially screening for psychiatric disorders among patients who present with BPPV. While the association between BPPV and depression did not reach statistical significance, there appears to be some association between BPPV and anxiety. This emphasizes the need to treat multiple domains of health in patients with peripheral vestibulopathies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors have made substantial contributions to all the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted. No writing assistance was obtained in the preparation of the manuscript. The manuscript, including related data, figures and tables has not been previously published and that the manuscript is not under consideration elsewhere.