Septal Perforation Repair Using Bilateral Mucosal Flaps With a Temporalis Fascia Interposition Graft

Editor's Note: This Manuscript was accepted for publication on September 8, 2020.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests or financial disclosures. This material has never been published and is not currently under evaluation in any other peer-reviewed publication.

Presented as a podium presentation at Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting, Cornonado, CA, January 23rd 2020.

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Numerous techniques attempting to close perforations of the nasal septum have been described. Fairbanks pioneered the “flap and graft” technique in 1970.1 His procedure utilized bilateral nasal mucosal flaps with an autogenous tissue graft interposed between the flaps. Cited advantages of this repair were the use of well-vascularized physiologic tissue in a single-staged procedure. The interposition graft provided both support for the closure and a third layer barrier to reperforation.

A 2012 systematic review on surgical perforation repair concluded procedures utilizing bipedicle mucosal flaps reported the highest closure rates.2 An updated review of subsequent publications found no statistical difference between multilayer flap, unilateral flap, and substrate (scaffolding) graft procedures.3 The lack of a standardized reporting system for perforation size and symptoms has hindered outcome comparisons between closure techniques.4

The senior author has attempted over 400 perforation repairs utilizing bilateral mucosal flaps with an interposition graft. An endonasal technique using three bipedicle mucosal flaps with a temporalis fascia interposition graft is demonstrated in this report.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study approval was granted through the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. A retrospective chart review was performed of the senior author's (S.F.B.) experience attempting closure of septal perforations utilizing bilateral nasal mucosal flaps with an interposition graft from November 1991 thru December 2019. Patients with minimum of three-month follow-up who underwent a repair utilizing a standard superior bipedicle advancement flap and inferior bipedicle advancement flap on the left side, combined with an inferior bipedicle flap on the right side and a temporalis fascia interposition graft defined the study cohort. Fundamental surgical maneuvers for attempted closure of moderate sized perforations are described subsequently and demonstrated in the video. Patients with repairs that used only one flap on the left side, a posterior rotational flap, or interposition graft material other than temporalis fascia were excluded from this study. Repairs which incorporated mucosa from the ventral surface of the upper lateral cartilage into the superior flap were also excluded.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Mucosal Flap Elevation

A right hemitransfixion incision is made (right-handed surgeon) and mucoperichondrial and periosteal elevation proceed on the left side to the perforation's anterior and superior margins. The elevation contours the perforation margin which is then incised with a #15-blade. The remainder of the perforation circumference is rimmed with the scalpel and mucoperichondrial and periosteal elevation proceed posteriorly, superiorly, inferiorly, and laterally to the inferior meatus with the extent of elevation dictated by perforation size and location. Our case study demonstrates elevation of mucosa extending from the attachment of the upper lateral cartilage to the inferior meatus. Right-sided mucosal elevation proceeds through the perforation and then inferiorly and laterally to the inferior meatus.

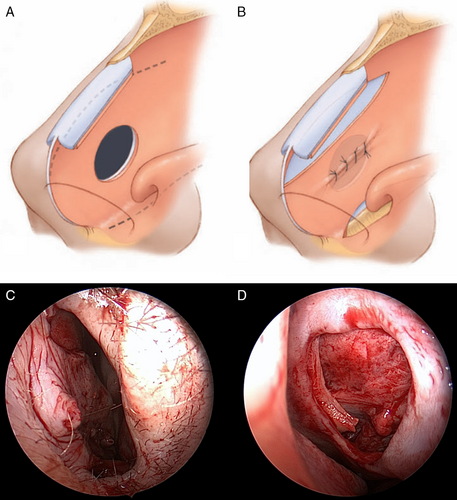

Left Superior and Inferior Bipedicle Flap Development and Perforation Closure

Perforation closure is performed on the left side using mucosa superior and, if necessary because of perforation size, inferior to the perforation to achieve complete coverage of the defect. The septal incision creating the superior flap is performed with a #15 blade near the upper lateral cartilage attachment and extends anteriorly to the valve angle while posteriorly arcing behind the perforation (Fig. 1A).

Inferior bipedicle flap development begins with monopolar cautery to incise the lateral nasal vestibule to the piriform aperture anterior to the head of the inferior turbinate. Mucosal elevation then connects with the prior nasal floor mucoperiosteal elevation. Flap incision is made with a long, curved scissors and extends from just below the inferior turbinate posteriorly within the inferior meatus before crossing the nasal floor posterior to the perforation (Fig. 1A).

The position and extent of left-sided incisions vary with perforation size and position. The incisions proceed up to 2 cm beyond the perforation posterior margin for larger defects to allow for flap release, advancement, and a tension-free closure. Interrupted 4–0 chromic sutures (Fig. 1B–D) on a P-3 needle (Ethicon) are used for the closure.

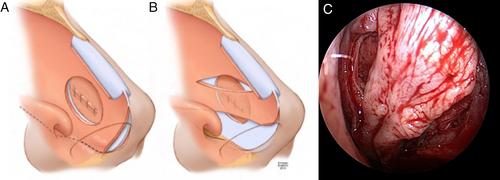

Right Inferior Bipedicle Flap Development and Advancement

The hemitransfixion incision is extended posteriorly and laterally before crossing the nasal floor posterior to the perforation (Fig. 2A). The flap is advanced superiorly to oppose the left suture line, is rarely fixated with sutures, and for most moderate to large perforations does not completely cover the defect (Fig. 2B,C).

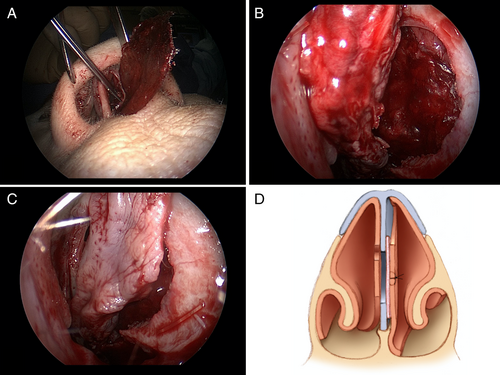

Interposition Graft Placement

Temporalis fascia is obtained at the beginning of the procedure. Enough fascia is harvested to fold over to double thickness and overlap the defect's margins. The graft is dried on a cartilage cutting block prior to insertion through the hemitransfixion incision and placement against the left-sided closure (Fig. 3A,B). The right inferior flap is repositioned to support the graft and oppose the left suture line (Fig. 3C,D).

Placement of Protective Silastic Sheeting and Telfa™ Gauze

The repair is protected with 0.02 inch polymeric silicone (Silastic) sheeting secured with a single nylon suture and bolstered bilaterally with Telfa™ gauze pads. The packing is removed in 2 days and the sheeting in 10–14 days.

RESULTS

The senior author performed 83 perforation repairs from November 1991 through December 2019 using the endonasal 3-flap with temporalis fascia graft technique demonstrated in the video. Three-month minimum postoperative follow-up was available in 75 patients. Demographic and perforation data for this cohort are presented in Table I. The mean follow-up was 24 months (range, 3–136 months). There was no instance of reperforation in any of the study patients. Nine patients underwent revision nasal surgery for persistent postoperative nasal obstruction. Left-sided swell body reduction was performed in eight patients as a stand-alone procedure. The remaining patient underwent revision left-sided external nasal valve surgery utilizing an alar batten graft.

| Characteristic | Sample Distribution |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range) | 51 (19–77) yr |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 30 (40%) |

| Female | 45 (60%) |

| Size | |

| Mean height (range), mm | 12 (5–25) mm |

| Mean length (range), mm | 17 (6–45) mm |

| Etiology, n (%) | |

| Prior septal surgery | 33 (44%) |

| Nasal trauma | 11 (15%) |

| Chemical cautery | 5 (7%) |

| Cocaine | 5 (7%) |

| Digital trauma | 4 (5%) |

| Corticosteroid spray | 2 (3%) |

| Decongestant spray | 2 (3%) |

| Other | 4 (5%) |

| Idiopathic | 9 (12%) |

DISCUSSION

Our repair technique emphasizes a complete, tension-free closure on the left side. Preoperative planning for flap number and design takes into account perforation position, relative size, and distance to the internal nasal valve angle and nasal floor. A single superior or inferior flap can achieve closure for smaller perforations. Mucosa from the undersurface of the upper lateral cartilage can be incorporated into the superior flap for vertically longer perforations or those approaching the internal valve angle. This maneuver is facilitated through the use of an intercartilaginous incision and is considered when the distance from the perforation to the valve angle is less than 50% of the perforation vertical height. For most perforations with a vertical height of 5–15 mm, the technique described in this report using a standard superior and inferior bipedicle flap on the left side will achieve a complete, tension-free closure.

The septum inferior to the perforation and adjacent nasal floor on the right side provides the mucosa for an inferior bipedicle flap. Mucoperichondrial elevation and flap development superior to the perforation on the right side is avoided to minimize the risk of cartilage devascularization, necrosis, and reperforation.1

Our choice of autogenous interposition graft material is generally determined by clinical circumstances and includes temporalis fascia, septal cartilage, or auricular perichondrium. Septal cartilage is used for smaller perforations if available. The ear can provide both cartilage for structural or aesthetic grafting and perichondrium for the perforation repair. Temporalis fascia is preferred for larger perforations and those smaller perforation in which septal cartilage was removed at the time of a prior procedure. Temporalis fascia is available in large quantity, is easy to harvest with low donor site morbidity, and readily integrates into the repair.2 We favor a soft tissue graft for larger perforations because of the risk of cartilage extrusion through the right side of the repair. Review of our experience with interposition grafts will be the subject of a future study.

Placement of silastic sheeting and nasal packs conclude the procedure. Nasal packing tamponades and bolsters the repair to promote graft stabilization and vascular ingrowth. Sheeting protects the repair from desiccation and dehiscence, promotes mucosal migration across the flap donor sites, and protects against problematic valve angle scarring and nasal synechiae. Patients are prepared for hard palate paresthesia lasting 3–4 weeks and nasal congestion lasting 3–4 months.

Timely and successful perforation closure prevents further problematic perforation enlargement and the increased surgical challenge associated with larger perforations. Crusting, obstruction, and epistaxis are the most common symptoms reported with a perforation. Nasal obstruction may be multifactorial and require additional procedures, either performed concurrent to repair or staged. Symptom resolution outcomes among the varied closure techniques have not been well studied. We have noted occasional persistent postoperative left-sided obstruction resulting from the inferior displacement of the nasal swell body (septal turbinate) contained within the superior bipedicle flap.5 Swell body soft tissue and septal cartilage/bone, if present, is resected submucosally. Swell body reduction was performed in eight patients without incidence of reperforation. All patients reported improvement in nasal obstruction following swell body reduction. There was no instance of nasal valve scarring. Placement of the standard superior flap incision avoids demucosalization of both margins of the valve angle and subsequent formation of a synechium.

Mucosal flap procedures are frequently used when attempting repair of the perforated septum. An endonasal, bilateral, 3-flap procedure achieving 100% closure success is presented in this report. High closure rates are reported by others using varied repair techniques. Standardization of perforation evaluation and symptom resolution outcomes may provide information to optimize septal perforation treatment.