Ultrasound Assessment of Entheseal Sites and Anterior Chest Wall in Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Cross-Sectional Study

Haiqin Xie, Gengmin Zhou, and Haiyu Luo contributed equally to this study.

A previous version of this manuscript was published as a preprint. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-95578/v1.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abstract

Objectives

The study was designed to evaluate entheseal sites and anterior chest wall (ACW) of patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) using ultrasound (US) and investigate the correlation between disease activity and US score.

Methods

This prospective cross-sectional study included 104 patients with AS and 50 control subjects. Each patient underwent US scanning of 23 entheses and 11 sites of the ACW. The US features, including hypoechogenicity, thickness, erosion, calcification, bursitis, and Doppler signal, were evaluated. Disease activity was assessed based on C reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), disease activity score-C reactive protein (ASDAS-CRP), and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI).

Results

The most commonly involved entheses on US were the Achilles tendon (AT) and quadriceps tendon (QT). The most involved site of ACW was the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ). Compared with the control group, significant differences were observed in the AS group in the rates of US enthesitis and ACW in AT (P = .01), SCJ (P = .00), and costochondral joint (CCJ) (P = .01). Patients with high or very high disease activity had a higher erosion score (P = .02). The erosion score was weakly positively associated with CRP, ESR, BASDAI, ASDAS-CRP, and ASDAS-ESR (correlation coefficient: 0.22–0.45).

Conclusions

The most commonly involved entheseal sites on US were AT and QT, while the site of ACW was SCJ. The US assessment of AS should take the ACW into account. High disease activity might indicate erosion in AS.

Abbreviations

-

- ACW

-

- anterior chest wall

-

- AS

-

- ankylosing spondylitis

-

- ASDAS-CRP

-

- ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score–C reactive protein

-

- ASIS

-

- anterosuperior iliac spine

-

- AT

-

- Achilles tendon

-

- BASDAI

-

- bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CCJ

-

- costochondral joint

-

- CET

-

- common extensor tendon

-

- CFT

-

- common flexor tendon

-

- CT

-

- computed tomography

-

- DPT

-

- distal patella tendon

-

- ESSR

-

- European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology

-

- GUESS

-

- Glasgow Ultrasound Enthesitis Scoring System

-

- HLA-B27

-

- human leukocyte antigen B27

-

- LCL

-

- lateral collateral ligament

-

- MCL

-

- medial collateral ligament

-

- MRI

-

- magnetic resonance imaging

-

- MSJ

-

- manubriosternal junction

-

- OMERACT

-

- Outcome Measures in Rheumatology

-

- PF

-

- plantar fascia

-

- PPT

-

- proximal patella tendon

-

- PROMs

-

- patient-reported outcome measures

-

- PS

-

- pubic symphysis

-

- QT

-

- quadriceps tendon

-

- SCJ

-

- sternoclavicular joint

-

- SD

-

- standard deviation

-

- SST

-

- supraspinatus tendon

-

- US

-

- ultrasound

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease characterized by enthesitis and primarily involves the axial skeleton, commonly occurring in young males.1 Sacroiliitis is one of the earliest manifestations and peripheral enthesitis is another characteristic of AS. It can cause physical damage and disability, reducing the life quality of patient and increasing the financial burden on both individuals and society. The prevalence of AS ranges from 0.1 to 0.9%.2 Early diagnosis and treatment can decrease the probability of disability and improve patient outcomes. However, due to the absence of both radiographic sacroiliitis and impaired spinal mobility at early stages of the disease, the diagnosis of AS is usually delayed by an average of 6–9 years after the onset of clinical symptoms.3, 4 Even at 10 years from the first presentation, 25–35% of patients still do not have radiographic sacroiliitis.5 Enthesitis is a characteristic sign of AS. It has been validated that enthesitis is important for the diagnosis of AS and monitoring disease activity.6 Hence, imaging methods that facilitate evaluation of enthesitis are of clinical values in diagnosing AS.

X-ray is the first line of investigation for the evaluation of enthesitis, although changes may occur at the late phase. Computed tomography (CT) can demonstrate bone erosion, but it is limited by radiation hazard and low resolution of soft tissue. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been considered more valuable, as it can quantify active inflammatory lesions of sacroiliac joints and entheses.7 Nonetheless, MRI is limited by its low availability and high cost. Further, it cannot assess many entheses due to long examination time. Ultrasound (US), a cheap, portable, non-radiation, and real-time imaging modality, is becoming increasingly accepted by rheumatologists as appropriate for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal diseases.

Studies have reported that US can be used to evaluate enthesitis for disease diagnosis, even in the early stages of spondyloarthritis.8-11 Some of these studies reported AS as the main type of spondyloarthritis.10, 11 According to the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) definitions, elementary lesions of enthesitis in US examinations include hypoechogenicity, increased thickness at enthesis, erosions, calcifications, and Doppler signal at insertion.12 However, it remains unclear which sites should be evaluated for enthesitis. Most studies have focused on the lower limbs,11, 13, 14 while some others investigated the upper and lower limbs.15, 16 Few studies pay attention to the anterior chest wall (ACW).17 The ACW has been demonstrated as the second most commonly involved site in spondyloarthritis just behind the sacroiliac joint.18 Until now, it is still highly controversial whether US associate with disease activity.19-21 Further studies are required to assess whether disease activity is correlated with US elemental lesions.

To further investigate the role of US in evaluating enthesitis in AS patients, we conducted this prospective cross-sectional study. The main objective of the present study was to evaluate the commonly involved entheses in AS, including the upper limbs, lower limbs, trunk, and particularly ACW. Furthermore, the correlations between disease activity of AS and US scores were analyzed to determine whether US enthesitis can be used to monitor disease activity in AS.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Study Design

This was a prospective cross-sectional study with a healthy control group. The study was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki principles and local regulations. The approval was permitted by the ethical committee of Peking University Shenzhen Hospital. All patients and healthy individuals signed informed consents.

The study finally included 104 patients with AS who fulfilled the modified New York criteria from December 2017 and December 2019.22 All the patients were consecutively enrolled from the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology at Peking University Shenzhen Hospital.

Patients were excluded if meeting any of the following exclusion criteria: joint or ACW surgery history, corticoid injection at the enthesis within the last 6 weeks, peripheral neuropathy, age <18 years, diseases other than AS, and unwillingness to sign informed consent, or failure to complete all the examinations or patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Controls

Fifty healthy participants were matched with AS patients in age, gender, and body mass index (BMI). They were selected from hospital workers and healthy volunteers who did not have any symptoms at the entheses and the ACW, were not diagnosed with spondyloarthritis, or had a family history of spondyloarthritis.

Data Collection

Data was collected based on PROMs, laboratory data, and US assessments. All patients were examined by a qualified rheumatologist. The rheumatologist used PROMs. For each patient, the laboratory tests consisted of C reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27). Disease activity was assessed by Disease Activity Score-CRP (ASDAS-CRP), Disease Activity Score-ESR (ASDAS-ESR), and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI). The interval between laboratory tests and ultrasound examination was <1 week. The ASDAS-CRP value (VASDAS-CRP) indicated the disease activity of AS. When the value was <1.3, the disease was inactive. When the value was 1.3 ≤ VASDAS-CRP < 2.1, the disease activity was low. When the index was 2.1 ≤ VASDAS-CRP < 3.5, the disease activity was high. When the index was ≥3.5, the disease activity was very high. BASDAI is a self-assessment tool to measure disease activity. It consists of six questions, and each question is scored from 0 to 10. When the overall score is ≥4, it indicates disease activity. Otherwise, it indicates disease inactivity. A higher score reflects a more active disease.

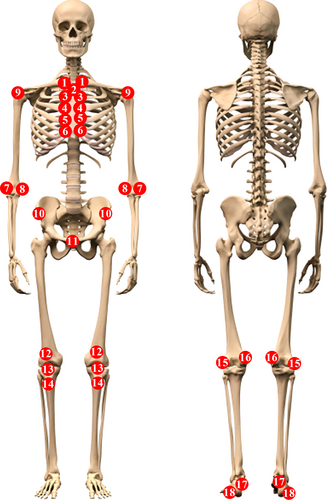

US Assessment

Ultrasonography was performed using Toshiba Aplio 400 equipment with a linear transducer at a frequency of 7–18 MHz by an experienced sonographer who performed musculoskeletal US for >5 years. Each subject was scanned by one sonographer. All subjects were examined by gray scale and power Doppler US. Doppler was set to a pulse repetition frequency of 1000 Hz, low wall filter, and Doppler gain at a level of just below random noise. The sonographer was blinded to clinical information, and patients were advised not to talk with the US examiner. US was used to evaluate 23 entheses in the upper limbs, lower limbs, and trunk, in combination with 11 sites of ACW (Figure 1). The upper limbs contained three bilateral entheses: common extensor tendon (CET), common flexor tendon (CFT), and supraspinatus tendon (SST). The lower limbs were comprised of seven bilateral entheses: quadriceps tendon (QT), proximal patella tendon (PPT), distal patella tendon (DPT), lateral collateral ligament (LCL) on the lateral femoral condyle, medial collateral ligament (MCL) on the medial femoral condyle, Achilles tendon (AT) on the calcaneus, and plantar fascia (PF). The trunk consisted of two entheses: the bilateral anterosuperior iliac spine (ASIS) and the single pubic symphysis (PS). The ACW included three sites: bilateral sternoclavicular joint (SCJ), single manubriosternal junction (MSJ), and costochondral joint (CCJ), in which the CCJ included eight bilateral locations from the 2nd to 5th ribs. Each site was scanned in both longitudinal and transverse planes and the images were saved. Examinations of the SST, CET, and CFT were performed in a sitting position. The QT, PPT, DPT, LCL, and MCL were assessed with the individual in the supine position with knee flexion at 30°–60°. The AT and PF were examined in a prone position with the feet hanging off of the bedside. The remaining entheses were evaluated in a supine position with the elbow contacting the body. All standardized examinations followed the European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology (ESSR).

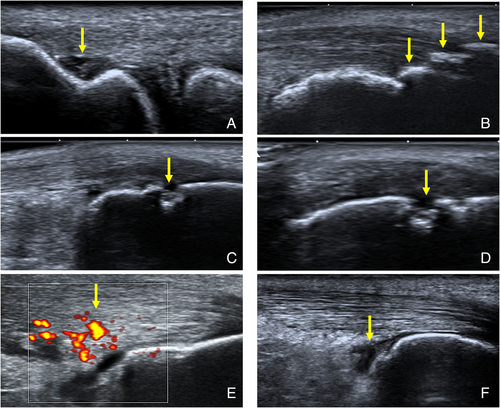

US Definition

The elementary US lesions of enthesitis and the involvement of ACW were as follows (Figure 2): 1) hypoechogenicity with lack of the normal homogeneous fibrillar pattern, 2) increased thickness measured at the insertion of 2 mm near the bone cortex, where the data followed the Glasgow Ultrasound Enthesitis Scoring System (GUESS).11 Except for PPT, DPT, QT, AT, and PF, increased thickness measured by bilateral comparison. However, if bilateral sites were involved, the shape was changed according to the healthy control, 3) bone erosion with cortical breakage with contour defect in both longitudinal and transverse planes, 4) calcification: hyperechoic foci or bony prominence at the end of the bone contour, with or without acoustic shadow. Calcification, ossification, and enthesophytes were sometimes similar in US images, making it difficult to differentiate between them. To simplify the description, ossification and enthesophytes were also considered as calcification, as several other reports have made the same decision,12, 23 5) bursitis: the locations of bursitis consisted of suprapatellar, infrapatellar, and retrocalcaneal bursas, with the normal anteroposterior diameter being <5, 2, and 3 mm, respectively,24 and 6) Doppler signal at the insertion 2 mm near the bone surface with the tendon or ligament in a relaxed position. Lesions of US scores were followed the Madrid sonography enthesitis index (MASEI)10: calcification (0–1–2–3), erosion (0 or 3), Doppler signal (0 or 3), hypoechogenicity (0–1), increased thickness (0–1), and bursitis (0–1). The US images were read by two sonographers. Any disagreement was resolved by involving a third sonographer's opinion. US enthesitis was defined by the presence of at least one abnormal entheses at one site. Each subject with US scores ≥1 point were classified as positive to compare the total numbers of US involved entheses between the AS groups and control groups.

Statistical Analysis

Variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A Student's t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used for quantitative analysis. Chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test when appropriate) was used for the categorical data. Correlations between disease activity and US scores were analyzed using Pearman's or Spearman's test. The correlation coefficient was interpreted as follows: negligible correlation: r < .30, low positive correlation: .30 < r < .50, moderate positive correlation: .50 < r < .70, high correlation: .70 < r < .90, very high positive correlation: r > .90.25 Values of P < .05 were considered as significant. SPSS version 23.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for all data analysis.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Data

The study finally enrolled 104 out of 247 potential subjects with AS (Figure 3). Furthermore, 50 control subjects were included. There were 23 entheses and 11 sites of ACW based on US assessment of each person. Thus, a total of 5236 locations were evaluated, consisting of 3536 sites in patients with AS and 1700 sites in controls. The AS and control groups were matched in age, gender, and BMI. The demographic and clinical data were summarized in Table 1. Most patients with AS were male (71.15%) and 94.23% of patients were tested positive for HLA-B27.

| AS Group (n = 104) | Control Group (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female/male | 30/74 | 8/42 | .018 |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 33.34 ± 8.32 | 33.44 ± 8.52 | .95 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 22.73 ± 1.87 | 22.69 ± 1.87 | .91 |

| Disease duration, years (mean ± SD) | 8.00 ± 6.66 | — | — |

| HLA-B27 (%) | 94.23 | — | — |

| CRP, mg/L (mean ± SD) | 16.33 ± 21.67 | — | — |

| BASDAI (mean ± SD) | 2.73 ± 1.68 | — | — |

| ASDAS-CRP (mean ± SD) | 2.52 ± 0.93 | — | — |

- —, not available; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASDAS-CRP, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score-CRP; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; HLA-B27, human leukocyte antigen B27; SD, standard deviation.

Commonly Involved Entheses and ACW in AS

Each patient carried 15 different sites within a total of 34 locations. Exactly 40–50 minutes of scanning was taken for each case. The total numbers of US involved entheses in the AS groups and control groups were significantly different, 20.16% (713/3536) and 9.65% (164/1700), respectively (P < .001). The most commonly involved entheses were AT and QT, while the site of ACW was SCJ (Table 2). However, compared with the control group, the rates of US involvement in three locations (AT, SCJ, and CCJ) showed significant differences in the AS group (P = .01, .00, and .01, respectively).

| AS Group (n = 104) | Control Group (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 73 (70) | 24 (48) | .01* |

| QT | 53 (51) | 26 (52) | .90 |

| SCJ | 34 (33) | 4 (8) | .00* |

| DPT | 18 (17) | 8 (16) | .84 |

| CET | 14 (13) | 4 (8) | .32 |

| SST | 14 (13) | 2 (4) | .07 |

| CCJ | 12 (11) | 0 (0) | .01* |

| MSJ | 8 (8) | 4 (8) | 1.00 |

| PPT | 6 (6) | 2 (4) | .18 |

| PF | 6 (6) | 0 (0) | .18 |

| ASIS | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | .55 |

| CFT | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| PS | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| MCL | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| LCL | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

- —, not available; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASIS, anterosuperior iliac spine; AT, Achilles tendon; CCJ, costochondral joint; CET, common extensor tendon; CFT, common flexor tendon; DPT, distal patella tendon; LCL, lateral collateral ligament; MCL, medial collateral ligament; MSJ, manubriosternal junction; PF, plantar fascia; PPT, proximal patella tendon; PS, pubic symphysis; QT, quadriceps tendon; SCJ, sternoclavicular joint; SST, supraspinatus tendon; US, ultrasound.

- * P < .05 between two groups.

Comparing US Scores in Different Groups Based on ASDAS-CRP and BASDAI Assessment

In contrast to the control group, the AS group manifested higher US scores, hypoechogenicity, thickness, erosion, and Doppler signal were higher, except for calcification and bursitis, as shown in Table 3.

| AS Group (n = 104) | Control Group (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US scores | 10.39 ± 11.06 | 3.96 ± 3.54 | <.01* |

| Hypoechogenicity | 1.31 ± 1.86 | 0.32 ± 0.68 | <.01* |

| Thickness | 0.98 ± 1.77 | 0.20 ± 0.57 | <.01* |

| Erosion | 1.36 ± 2.92 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | <.01* |

| Calcification | 3.48 ± 3.99 | 2.68 ± 2.84 | .29 |

| Bursitis | 0.79 ± 1.17 | 0.76 ± 0.92 | .75 |

| Doppler signal | 2.48 ± 3.61 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | <.01* |

- AS, ankylosing spondylitis; US, ultrasound.

- * P < .01 between the AS group and the control group.

The US scores did not show significant differences between patients with disease activity (ASDAS-CRP ≥ 1.3) and those with disease inactivity (ASDAS-CRP < 1.3), as seen in Table 4. In addition, patients with high disease activity (ASDAS-CRP ≥ 2.1) had higher scores compared with patients with low activity (ASDAS-CRP < 2.1) in erosion (P = .02) and bursitis (P = .04). Patients with very high disease activity (ASDAS-CRP ≥ 3.5) had a higher score in erosion (P = .02).

| ASDAS-CRP | ASDAS-CRP | ASDAS-CRP | BASDAI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1.3 | <1.3 | P | ≥2.1 | <2.1 | P | ≥3.5 | <3.5 | P | ≥4 | <4 | P | |

| US scores | 10.27 ± 10.12 | 11.88 ± 20.19 | .54 | 10.93 ± 10.15 | 9.34 ± 12.76 | .11 | 11.21 ± 11.91 | 10.27 ± 10.99 | .81 | 13.43 ± 13.26 | 9.53 ± 10.29 | .16 |

| Hypoechogenicity | 1.26 ± 1.64 | 1.88 ± 3.76 | .71 | 1.29 ± 1.57 | 1.34 ± 2.35 | .43 | 4.86 ± 5.02 | 4.83 ± 5.02 | .81 | 1.74 ± 2.09 | 1.19 ± 1.78 | .19 |

| Thickness | 0.90 ± 1.52 | 2.00 ± 3.70 | .32 | 0.96 ± 1.55 | 1.03 ± 2.18 | .42 | 1.21 ± 2.42 | 0.94 ± 1.67 | .96 | 1.35 ± 2.23 | 0.88 ± 1.62 | .32 |

| Erosion | 1.47 ± 3.02 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | .09 | 1.78 ± 3.31 | 0.51 ± 1.70 | .02* | 2.57 ± 3.08 | 1.17 ± 2.87 | .02* | 2.09 ± 4.00 | 1.15 ± 2.54 | .11 |

| Calcification | 3.28 ± 3.28 | 5.88 ± 9.01 | .68 | 3.32 ± 3.06 | 3.80 ± 5.43 | .64 | 2.29 ± 2.946 | 3.67 ± 4.12 | .14 | 3.04 ± 3.27 | 3.62 ± 4.19 | .54 |

| Bursitis | 0.83 ± 1.20 | 0.25 ± 0.46 | .17 | 0.97 ± 1.32 | 0.43 ± 0.70 | .04* | 0.57 ± 0.76 | 0.82 ± 1.22 | .73 | 1.30 ± 1.52 | 0.64 ± 1.02 | .02* |

| Doppler signal | 2.53 ± 3.57 | 1.88 ± 4.22 | .36 | 2.61 ± 3.74 | 2.23 ± 3.36 | .64 | 3.00 ± 4.71 | 2.40 ± 3.43 | .97 | 3.91 ± 4.65 | 2.07 ± 3.17 | .07 |

- ASDAS-CRP, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score-C reactive protein; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; US, ultrasound.

- * P < .05 between two groups.

Correlations between Disease Activity and US Scores in AS

The correlation coefficients between US features and clinical indexes are listed in Table 5. US scores, and some of the US features, including erosion, Doppler signal, and hypoechogenicity, correlated with ESR and CRP, with the correlation coefficient ranging from 0.19 to 0.44. Bone erosion showed the highest correlation with CRP and ESR. US scores, bursitis, erosion, and Doppler signal also correlated with ASDAS-CRP, while only erosion was correlated with BASDAI. Calcification, increased thickness, and hypoechogenicity did not correlate with the disease activity scores. The correlation coefficient between erosion and disease activity score ranged from 0.22 to 0.45 (Table 5). Bone erosion also had the highest correlation coefficient with ASDAS among US features (correlation coefficient between erosion and ASDAS-CRP and ASDAS-ESR: 0.45 [0.28–0.59] and 0.45 [0.28–0.59], respectively, P < .001 for both).

| CRP | ESR | BASDAI | ASDAS-CRP | ASDAS-ESR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r (95% CI) | P | r (95% CI) | P | r (95% CI) | P | r (95% CI) | P | r (95% CI) | P | |

| US scores | 0.27 (0.08–0.44) | .01* | 0.27 (0.08–0.44) | .01* | 0.08 (−0.11 to 0.27) | .42 | 0.22 (0.02–0.39) | .03* | 0.21 (0.02–0.39) | .03 |

| Hypoechogenicity | 0.21 (0.02–0.39) | .03* | 0.20 (0.00–0.37) | .05* | 0.04 (−0.16 to 0.23) | .71 | 0.12 (−0.07 to 0.31) | .21 | 0.12 (−0.07 to 0.31) | .22 |

| Thickness | 0.17 (−0.02 to 0.35) | .08 | 0.19 (0.00–0.37) | .05* | 0.01 (−0.18 to 0.20) | .90 | 0.09 (−0.11 to 0.27) | .39 | 0.09 (−0.10 to 0.28) | .36 |

| Erosion | 0.35 (0.17–0.51) | <.01* | 0.45 (0.28–0.59) | <.01* | 0.22 (0.03–0.39) | .03* | 0.45 (0.28–0.59) | <.01* | 0.45 (0.28–0.59) | <.01* |

| Calcification | 0.02 (−0.17 to 0.21) | .83 | 0.02 (−0.17 to 0.21) | .83 | −0.18 (−0.36 to 0.01) | .07 | −0.13 (−0.31 to 0.07) | .19 | −0.12 (−0.30 to 0.08) | .23 |

| Bursitis | 0.15 (−0.04 to 0.33) | .13 | 0.02 (−0.18 to 0.21) | .88 | 0.19 (0.00–0.37) | .05 | 0.23 (0.04–0.41) | .02* | 0.15 (−0.04 to 0.33) | .13 |

| Doppler signal | 0.27 (0.09–0.44) | <.01* | 0.25 (0.06–0.42) | .01* | 0.18 (−0.01 to 0.36) | .07 | 0.26 (0.07–0.43) | .01* | 0.27 (0.08–0.44) | .01* |

- ASDAS-CRP, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score-C reactive protein; ASDAS-ESR, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score-erythrocyte sedimentation rate; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; MASEI, Madrid Sonography Enthesitis Index; US, ultrasound.

- * P < .05 between two groups.

Discussion

In this study, a total of 5236 sites of entheses and ACW of 104 patients with AS and 50 healthy controls were evaluated. To the best of our knowledge, it was by far the largest number of locations on US evaluation. AT and QT were the most commonly involved entheses on US, while SCJ was the mostly involved ACW site. The rate of US enthesitis in AT showed significant differences in the AS group compared with the control group, similar to the SCJ and CCJ in ACW. Patients with high or very high disease activity had a higher score in erosion (P = .02). The erosion score was weakly correlated CRP, ESR, BASDAI, ASDAS-CRP and ASDAS-ESR with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.22 to 0.45.

In the present study, the most commonly involved entheses were AT and QT. Moreover, SCJ was the most commonly involved site in ACW. These findings can be explained by biomechanics—AT was the site experiencing frequent movement, QT was the site supporting the body, and SCJ was the site connecting the trunk and upper limbs.26 Furthermore, compared with the control group, the frequency of US features found in the three entheses (AT, SCJ, and CCJ) showed significant differences in the AS group. Considering the feasibility of screening for enthesitis in patients with AS, if only a limited number of entheses could be monitored by US, more could be found in AT and QT. In particular, involvement of the AT and SCJ may be of value in distinguishing AS from healthy subjects. Several studies reported that the rate of ACW involvement was 30–50% in spondyloarthritis.27, 28 A study reported that 44.6% of the DESIR cohort was clinically associated with the ACW in early spondyloarthritis.29 Compared with AT, which has been extensively explored by researchers, the ACW (including SCJ and CCJ) is often neglected in US evaluation of AS. Our study suggested that evaluation of ACW is an important imaging index for AS assessment in addition to the upper and lower limbs.

In clinical practice, several modalities are used to assess disease activity, including physical examination, laboratory tests (CRP, ESR), composite indices (BASDAI or ASDAS), and imaging examinations (x-rays, CT, MRI, or US). But the gold standard for monitoring disease activity remains a challenge in AS. Some studies have reported US as a valuable tool for monitoring disease activity and evaluation of therapeutic effect.20, 30, 31 However, one study from the DESIR cohort found that US was not helpful for monitoring disease activity in 402 patients with spondyloarthritis.21 The study showed that patients with high disease activity (ASDAS-CRP ≥ 2.1) or very high disease activity (ASDAS-CRP ≥ 3.5) had a higher erosion score, suggesting that erosion could occur more often in patients with disease activity. Among those US features, bone erosion was also associated with the largest number of disease activity parameters (ESR, CRP, BASDAI, ASDAS-CRP, ASDAS-ESR), but only a weak positive correlation (r = .45) between erosion and ASDAS-CRP and ASDAS-ESR was detected. De Miguel et al reported that Achilles erosion was a significantly associated with objective disease activity in spondyloarthritis.32 It appears that erosion could be correlated with disease activity in AS. However, this still needs to be validated in a larger population and longitudinal study whether erosion would be useful for monitoring disease activity.

Except for erosion, US features, including calcification, increased thickness, hypoechogenicity, erosion, and Doppler signal, hardly correlated with disease activity parameters in the current study. Neither this work nor many other previous studies revealed a high association between disease activity parameters and US scores.30, 33-35 One reason is that enthesitis is not only observed in spondylitis, but can also be seen noninflammatory tendinopathy (such as degenerative tendinopathy) and during intensive sport.36, 37 One limitation of the current study is that physical activity of the controls was not taken into account. On the other hand, the poor correlation between US features and disease activity might suggest that enthesitis tended to be independent from systemic inflammation in AS. Notably, calcification could be found in both the AS and control groups, without significant differences. Calcification in normal individuals may be attributed to repeated biological force or aging.38, 39

There were some limitations in the present study. First, the included patients were all inpatients, and most of them were males. Therefore, there were selection bias and gender bias. More female patients should have been consecutively recruited from the clinics. Second, the disease activity indexes did not contain physical examination data given its low sensitivity and specificity, which should be improved in further studies. Third, there were no standard quantitative metrics for the US features of the ACW and trunk, which might partly impair the stability of the US assessment. Fourth, both US examination and US scoring systems are operator-dependent. However, the intraobserver agreement κ coefficient of 0.74 in this study, which suggested a good intraobserver agreement. In this study, a total of 23 sites throughout the entire body were investigated for enthesitis to find which entheses were more involved. In further studies, a more simplified and time-saving version of US enthesis score with high reliability and repeatability should be explored to enhance the clinical promotion of US assessment for AS.

Conclusions

The most commonly involved entheseal sites and ACW based on US evaluation were AT, QT, and SCJ. Erosion occurred more often in patients with high or very high disease activity. Erosion may indicate a relatively high disease activity in patients with AS.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Shenzhen Hospital, with approval ID 2020030.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by Science, Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality in China (No. JCYJ20210324110015040), Financial support of Guangdong High-level hospital construction fund (No. GD2019260), Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (No. SZSM202111011), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2019A1515011112), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81974253).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.