Feeling alone in your subjectivity: Introducing the State Trait Existential Isolation Model (STEIM)

Abstract

Psychologists have devoted substantial attention to social isolation and to loneliness but only recently have psychologists begun to consider existential isolation. Existential isolation is a unique form of interpersonal isolation, related to, but distinct from loneliness and social isolation. Feeling existentially isolated is the subjective sense one is alone in one's experience, and that others cannot understand one's perspective. In the current paper, we propose a conceptual model of existential isolation and review relevant evidence. The model proposes that the experience of existential isolation can be situational, context dependent, or a trait-like pervasive sense that others do not validate one's subjective experience. The model posits acute and chronic causes of existential isolation and consequences of the state and trait forms of it. Reactions to state existential isolation produce momentary and short-term effects whereby an individual's sense of validation of their worldview is threatened and attempts are made to eliminate this feeling. In contrast, trait existential isolation leads to reduced identification with cultural sources of meaning and withdrawal from seeking rewarding relationships, which leads to more long-term consequences such as chronic need depletion and deficits in well-being. We briefly discuss potential moderators that may affect whether and when individuals experience existential isolation and possible strategies for reducing existential isolation, and recommend directions for future research.

By its very nature every embodied spirit is doomed to suffer and enjoy in solitude. Sensations, feelings, insights, fancies – all these are private and, except through symbols and at second hand, incommunicable. We can pool information about experiences, but never the experiences themselves.

Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception

In Existential Psychotherapy, Yalom (1980) defines existential isolation (EI) as the “unbridgeable gulf between oneself and any other being … [and as] an isolation even more fundamental—a separation between the individual and the world” (p. 355). Echoing Huxley, Yalom is pointing out that, regardless of whether people find themselves physically together or physically alone, in a relationship with another person or not, an impenetrable divide results from the way in which humans sense, perceive, interpret—in short, experience—stimuli.

There is a difference between this inherent isolation, however, and how much individuals actually experience EI. Although no one can truly know first-hand the experience of another (Mueller, 1834/1912), not everyone reports feeling this EI to the same extent. According to Pinel, Long, Murdoch, and Helm (2017), people who feel existentially isolated feel different from others with regard to their in-the-moment subjective experiences. In short, “people feel existentially isolated when they feel alone in their experience, as though nobody else shares their experience or could come close to understanding it” (Pinel et al., 2017, p. 55).

Thus, the experience of EI occurs when the individual feels like she or he has a unique perspective unshared by others around them. People seem to vary greatly in how much they have this feeling. The purpose of this paper is to present a conceptual model of EI, its causes and consequences, to present relevant evidence to date, and to point to future directions for research.

1 DISTINGUISHING EXISTENTIAL ISOLATION FROM OTHER FORMS OF INTERPERSONAL ISOLATION

Existential isolation is related to, but distinct from, two other forms of interpersonal isolation that have been studied: loneliness and social isolation. This distinction is in contrast to Yalom's (1980) conceptualization, where he distinguishes EI from interpersonal isolation. Other papers discussing EI (e.g., Pinel et al., 2017; Pinel, Long, Landau, & Pyszczynski, 2004) have made similar distinctions and used social isolation as an umbrella term that encompasses EI and other forms of isolation. However, a great deal of literature uses social isolation to refer to the objective condition of having few contacts with family and community (e.g., Pressman et al., 2005; Townsend, 1968) or to the absence of relationships with other people (e.g., De Jong Gierveld & Van Tillburg, 2006). Thus, here we are using interpersonal isolation as an umbrella term to be consistent with other researchers.

Interpersonal isolation broadly refers to any type of isolation or separation between individuals. Loneliness is the distressing feeling accompanied by the subjective evaluation that there is a discrepancy between one's desired and one's actual social relationships (Cacioppo et al., 2006; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014). Therefore, in contrast to social isolation, both loneliness and EI are subjective evaluations of how one relates to others. However, loneliness specifically refers to the presence or absence of fulfilling social relationships, whereas EI refers to the sense that others do not validate one's subjective experience of reality.

Empirical psychologists have only recently begun to consider EI as a construct worthy of study (e.g., Helm, Rothschild, Greenberg, & Croft, 2018; Pinel, Long, & Crimin, 2010; Pinel & Long, 2012; Pinel et al., 2017). Pinel and colleagues (2017) developed and validated the Existential Isolation Scale and established both its distinctness from commonly used measures of social isolation and its relevance to interpersonal and intergroup phenomena. The Existential Isolation Scale contains six items measuring the extent to which people feel as though they regularly differ from others with regard to their own subjective experience of stimuli. Example items include “other people usually do not understand my experiences,” and “people around me tend to react to things in the environment in the same way I do” (reverse coded).

In differentiating feelings of EI from other forms of interpersonal isolation, Pinel et al. (2017) correlated EI with a host of other constructs that tap forms of interpersonal isolation, including loneliness, the need to belong, and alienation. They found that EI correlated most with alienation (r = 0.32), loneliness (r = 0.34), and extroversion (r = −0.30). However, these constructs had reasonable divergent correlations. Whereas alienation was significantly correlated with need to belong and social desirability, EI was not. Further, the magnitude of the correlation between alienation and loneliness was much stronger than was the relationship between EI and loneliness. EI was negatively correlated with extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability.

Recent empirical investigations have established the importance of considering the construct of EI in our understanding of human psychology. Here, we offer an overarching theoretical framework that is meant to guide further investigations on this topic. We address questions about how existential isolation develops, its state and trait manifestations, and potential consequences of existential isolation.

2 INTRODUCING THE STATE TRAIT EXISTENTIAL ISOLATION MODEL

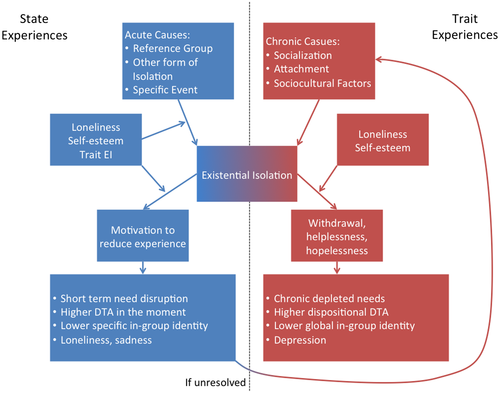

Ultimately, all humans—insofar as they can only know the outside world through their own sensory experience with it and not through others’ sensory experiences—are isolated in an existential sense—it is a fact of existence. However, differing circumstances may bring this awareness to the surface and cause an individual to feel existentially isolated. In particular, there may be both acute and chronic causes, leading to situational (state) or dispositional (trait) feelings of EI, which should engender different reactions to and outcomes (see Figure 1). Below we propose a conceptual model of EI, which specifies two types of EI: state or in-the-moment feelings and trait or generalized feelings.

Acute experiences, such as a specific event or comparing oneself to a particular reference group, can elicit state EI. State EI then serves to motivate the individual to reduce this experience and leads to short-term need disruption, higher death-thought accessibility, lower identity with any group associated with the experience, and loneliness. If the individual is unable to successfully reduce state EI, or if the individual has many such acute experiences, state EI can turn into trait EI. Trait EI is a generalized experience where an individual feels as though others generally do not, or cannot, understand their subjective experience. In addition to unresolved state EI, more chronic causes contribute to trait EI, including aspects of the socialization process and sociocultural factors. Unlike state EI, which motivates individuals to try and reduce the experience, trait EI leads to social withdrawal and feelings of hopelessness. Trait EI then leads to more chronically depleted needs, higher dispositional death-thought accessibility, lower global in-group identity, and increases vulnerability to depression.

In Table 1, we list a series of primary hypotheses that can be drawn from our model. Throughout the text, we will reference relevant hypotheses outlined in Table 1. We believe more hypotheses could be derived from the model based on the relationships among the constructs (e.g., hypotheses concerning the bidirectional relationship between EI, social isolation, and loneliness), but for the sake of brevity we limit ourselves to the primary hypotheses of our model.

| Hypothesis number | Hypothesis description |

|---|---|

| H1 | Instances that highlight an individual is having a different experience or reaction than others (either a person or group) should increase state EI. |

| H2 | Experiences of loneliness or social isolation can result in increased state EI. |

| H3 | Specific consequential life events that change an individual's perspective can lead to greater state, context dependent, or trait EI. |

| H4 | Individuals with insecure attachment, particularly avoidant attachment, are likely to experience greater trait EI than those with secure attachment. |

| H5 | Male socialization processes lead to higher levels of trait EI |

| H6 | Members of non-dominate groups should have higher EI than members of dominate groups. |

| H7 | Independent self-construal and individualism should be associated with higher trait EI. |

| H8 | Experiences of state EI lead to negative feelings, which motivate the individual to reduce those feelings. |

| H9 | State EI should produce short-term effects, such as short-term need disruption, higher death-thought accessibility, lower specific group identity, and loneliness. |

| H10 | State EI serves as a differentiation cue, which should motivate the individual to seek assimilation. |

| H11 | If state EI remains unresolved over weeks or months, it will increase trait EI. |

| H12 | Experiences of trait EI should lead an individual to feel helpless, hopeless, and to display withdrawal behaviors. |

| H13 | Those with trait EI should report chronically depleted needs, higher dispositional death-thought accessibility, lower group identity across groups, and higher depression. |

| H14 | Loneliness will moderate trait EI processes, such that those with higher EI and higher loneliness should be more likely to experience negative outcomes. |

| H15 | Loneliness will moderate state EI processes, such that those with higher loneliness should be both more likely to experience state EI when in a situation that makes EI salient, and those with higher loneliness should be more likely to experience negative outcomes once experiencing state EI. |

| H16 | Anxiety buffers, such as self-esteem, should moderate both state and trait processes, such that those with higher self-esteem should be less susceptible to experiencing state EI, should report less negative consequences after feeling state EI, and should report less negative consequences after having trait EI. |

| H17 | Trait EI should moderate state EI processes, such that those with higher trait EI should be more likely to experience state EI resulting from having or recalling different experiences than others, and should report greater negative consequences when experiencing state EI. |

Note

- Table lists the hypotheses numerically and follows the presentation of the hypotheses in the text. EI refers to existential isolation.

In the following sections, we break down each component of our model. We first consider the causes of both state and trait EI. We then consider reactions and outcomes to state EI, followed by reactions and outcomes to trait EI.

2.1 Causes

At a young age, humans develop a theory of mind (Baron-Cohen, 2000; Becker, 1971) and so realize that their subjective experience does not necessarily match another person's. By four years of age (Cadinu & Kiesner, 2000), children begin to realize they have access to their own inner worlds but are only able to come into contact with others externally—physically or via symbols (Becker, 1971). Once children have developed a theory of mind, they have the potential to experience at least an inchoate sense of EI. From that point on, the degree to which individuals actually experience EI depends upon a host of situational, psychological, and cultural variables. We delineate acute and chronic causes of experiencing EI in the next sections.

2.1.1 Acute causes

Acute causes are discrete events that lead to increases in EI. Their effects can range from a momentary increase in state EI to a more permanent increase in trait EI if the state feelings remain unresolved in general or in most social contexts. They may include a specific experience or set of experiences, one's situationally salient reference group, or the experience of another form of isolation.

Certain life events or experiences should create short-term feelings of EI. Generally, these events should highlight that an individual is having a different experience than others around them with regard to the same external stimuli (H1). This might be a singular event, such as standing up for something only you believe in or watching a movie you do not think is funny when everyone else is laughing. In this moment, it is not that two people are merely disagreeing on a topic, but rather the individual's experience is contrasted with the seemingly normative experience of others (i.e., the sense that most others are having a different experience than the individual).

An individual’s reference group may also affect the levels of EI. Because feeling EI involves some comparison, who or what the individual compares themselves to can contribute to feeling existentially isolated. Drawing on social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954), individuals make a self-evaluation against others with respect to their experiences, perceptions, reactions, and inner states. If an individual perceives himself or herself to have very different experiences from another (or another group), it may increase state EI (also H1). For example, one of the authors was giving a talk presenting some EI research and a community member raised her hand and stated that if she were taking the EI scale, she would not know how to respond. She said she had just moved to the area from out-of-state and into a retirement community, and would complete the scale very differently if she were thinking about her hometown than if she was thinking about her new community. In this case, depending on which group the individual was comparing herself to she felt differing amounts of EI. This reference group effect should be considered in research because participants may report different levels of EI depending on who the researcher asks the participants to think about when completing the scale.

Other forms of isolation (e.g., loneliness or social isolation) should also contribute to experiences of EI (H2). Yalom (1980) wrote that the boundaries between types of isolation are semipermeable and that one type can lead to another. For example, if someone starts to feel like they have fewer social connections than they desire (i.e., they feel lonely), it could start to manifest in feelings that others do not see the world as they do (i.e., feeling EI). Likewise, if someone is in a situation in life in which they have few social contacts and is socially isolated, eventually they may begin to feel as if their view of the world is not shared by other people. However, it is likely that these relationships are bidirectional. It is also possible that EI could increase feelings of loneliness in the short term. Different types of isolation thus should be correlated with one another, but EI and loneliness should be more correlated with each other than with social isolation, given that they are both subjective experiences.

When considering acute causes and state EI, it is also important to consider context-dependent processes. In some contexts, an individual may feel validated and understood, but in other contexts differences in perspective may be painfully clear. Following the logic of the personality and role identity structural model (PRISM; Wood & Roberts, 2006), general dispositions can vary depending on one's context-dependent role identity. In other words, someone may have a general tendency to feel like others understand their experiences in one role but not another. This perspective is supported by research that has found that different personality traits can manifest in response to different role demands (e.g., Neyer & Asendorpf, 2001; Roberts, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2003).

For example, an African American may feel EI when around primarily Euro Americans, but not feel EI when in their predominately African American neighborhood. Other examples could include an alcoholic who only feels understood when at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, or a member of the LGBTQ community struggling with EI when living in a conservative, not very inclusive community.

Specific consequential life events may change one's perspective leading to shifts in identity or social role, such as losing a parent, being diagnosed with a terminal illness, or experiencing a traumatic event. In this case, the individual's mindset or outlook shifts, leading them to feel that others are not understanding their experiences (H3). Consider the military veteran who experienced combat oversees and then returns to civilian life. Traumatic experiences during combat are not necessarily existentially isolating while the person is still in the military around others who have had similar experiences. However, once this person returns home, their context and reference groups change to civilians. Civilians without combat experience cannot possibly understand what it was like in combat situations, leaving the veteran to feel as though only others with that experience can relate to them (Greening, 1997; Herman, 1997). In his work with war veterans with PTSD, Rollo May (1999) noted that they “were unable to take part in the feelings and thoughts of others or share oneself with others” (p. 21). In this case, situations that make salient the discrepancy between the veteran's worldview (via the lens of trauma) and other civilian's worldview (without the lens of those experiences) produce elevated EI. This person's EI is context dependent because they only experience EI when around others without their military experiences. In preliminary support for this hypothesis, Helm and colleagues (Helm, Marchant, & Greenberg, 2018) found that student military veterans reported a standard deviation higher EI than did their non-veteran counterparts.

Each of the above examples outlines different circumstances that may foster experiences of EI that could be brief lived or context dependent. If the EI-eliciting context becomes prevalent in one's life, as for the veteran returned to civilian life, it becomes a trait-like general feeling of EI. However, chronic experiences, those occurring over long periods of time, are probably the most common causes of high trait EI. To date, most research on EI has focused on it as a trait and has conceptualized it as a stable individual difference (e.g., Costello, 2017; Helm, Lifshin, Chau, & Greenberg, 2018).

2.1.2 Chronic causes

Chronic causes that contribute to trait EI may occur because of attachment or other socialization processes, and sociocultural factors. Across multiple studies, researchers have found consistent correlations between EI and insecure attachment (Helm, Lifshin, & Greenberg, 2016, 2017). In particular, EI is correlated with avoidant attachment. Avoidant attachment is often marked by a self-reliant orientation where the individual is closed off from others and uncomfortable with intimacy (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Individuals may develop avoidant attachment to the extent that their primary caregivers were consistently unavailable (Bowlby, 1980). From an attachment perspective, one function of primary caregivers is to help the child orient to the world. Consistent and attentive caregivers successfully validate the child's experiences which help them develop mature self-efficacy, self-regulation, and the ability to balance self-reliance with reliance on others (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). In contrast, children with inconsistent or unavailable caregivers are left to rely on themselves to make sense of the world. Shared reality researchers (e.g., Echterhoff, Higgins, & Levine, 2009) argue secure attachment helps the individual feel as though they experience a more valid and reliable view of the world. Thus, if the caregivers are unavailable and do not validate or guide the child's perspective, the child must rely on their own sense of reality, thus leaving the child vulnerable to chronic feelings of EI (H4).

How individuals are gender-socialized may also contribute to trait EI (H5). Multiple studies have found consistent sex differences in reported EI (Costello, 2017; Helm, Lifshin, Chau, et al., 2018; Pinel et al., 2017) in which men report higher EI than do women. Helm, Lifshin, Chau, et al. (2018) found that sex differences in endorsing communal values helps explain this difference. Communal values revolve around valuing characteristics that are group-oriented (e.g., loyalty, equality) and prosocial (e.g., forgiveness, altruism). Thus, having a group-focused orientation and focusing on the needs or concerns of others is at least correlated with lower EI. These data suggest that sex role socialization according to prevailing cultural norms that discourage men (or other individuals) from displaying emotions and connecting to others may result in higher dispositional EI.

Turning to culture, Yawger, Pinel, Scharnetzki, Miller, and Helm (2018) reported that in the U.S., members of the nondominant groups (e.g., gay men and lesbians; Latinas/Latinos; people from low SES households) have higher levels of EI than members of the dominant groups (H6) (e.g., (heterosexuals; non-Latinos/non-Latinas; people from high SES households). Yawger et al. (2018) submit that these higher EI levels exist because members of the nondominant groups do not shape the cultural dialogue and thus the shared cultural reality (Echterhoff & Higgins, 2017) in the same way as members of the dominant groups. Generally, these data suggest that having identities that fall outside of the normative cultural script may contribute to dispositional EI, although again, this form of EI may be context dependent in that, when around people with the same stigmatized social identity, feelings of EI may be alleviated.

Broader sociocultural factors may also contribute to trait levels of EI (H7). In a recent study conducted by Park and Pinel (2018) in South Korea, EI was negatively associated with collectivism and importance of Korean identity. In American samples, Helm, Lifshin, and Greenberg (2018) have found EI to correlate negatively with collectivism and positively with individualism. This evidence is consistent with the negative correlation between EI and communal value endorsement noted earlier. Drawing on Markus and Kitayama's (1991, 2010) distinction between independent and interdependent self-construal, it is logical that individuals who see themselves as distinct and separate from others (independent self-construal) would feel more EI than individuals who see themselves as inherently interrelated to others (interdependent self-construal).

In summary, acute causes are discrete, time-limited events that provoke feelings that others do not understand one's perspective. In contrast, chronic causes are those with repeated or prolonged influence that consistently shapes the individual's perspective over time, leading to generalized trait EI. Among the most potent chronic causes are attachment style and other consequences of the socialization process.

2.2 Outcomes

2.2.1 Reactions and outcomes to state existential isolation

When feelings of EI become heightened in a particular situation (state EI), the individual should be motived to reduce the experience. Yalom (1980) writes, “the experience of EI produces a highly uncomfortable subjective state and…is not tolerated by the individual for long” (p. 362). Thus, feeling existentially isolated should lead to negative feelings, which in turn motivate an individual to reduce those feelings (H8).

State feelings of EI should produce short-term effects. These effects may include short-term need disruption, higher in-the-moment death-thought accessibility, lower specific in-group identity, and feelings of loneliness or sadness (H9). Because situational experiences of EI should be relatively short-lived, the effects should also be fairly brief.

Very little research has been conducted on state EI. But there are a few exceptions. Helm and colleagues (Helm, Lifshin, Chau, et al., 2018) found that priming feelings of EI increased death-thought accessibility relative to a loneliness or boredom prime. Death-thought accessibility refers to how accessible death-related cognition is in consciousness (Hayes, Schimel, Faucher, & Williams, 2008). This study is generally consistent with the anxiety buffer disruption theory (Pyszczynski & Kesebit, 2011) and the terror management theory (Hayes, Schimel, Arndt, & Faucher, 2010), which posit that traumatic events can disrupt the efficacy of one's anxiety buffer or worldview, which functions to provide a sense of security and safety to the individual. When one's worldview is threatened or undermined, death thoughts become more accessible in consciousness (e.g., Hayes et al., 2008). To the extent that our worldviews and cultural reality are substantiated by social validation (e.g., Berger & Luckmann, 1966), feelings of EI may undermine the strength and perceived validity of these worldviews.

In addition to threatening the strength of one's cultural worldview, situational reminders of EI should threaten one's self-esteem, sense of belonging or connection, meaning, and social integration. Again, because awareness of EI leaves the individual feeling alone in their experience, they feel vulnerable and less enmeshed with groups.

By extension, situational reminders of EI should also lower group identity especially with the group that causes or makes salient the separation. Group identity could mean importance of one's identity or feelings of closeness and affiliation with the group. In various studies attempting to prime EI using the open-ended prime used in Pinel et al. (2017), a reoccurring theme in participant responses has been that when participants report feeling disconnected (i.e., existentially isolated) from a particular group (e.g., from their fraternity, sports team, group of friends, etc.), they subsequently feel like outsiders and marginalized from that group. In other words, when participants recall an instance when they felt existentially isolated from a group, they often subsequently wrote about feeling less identified with that particular group. From a social identity perspective (Hogg, 2003; Tajfel, 1972), situations that increase awareness of one's EI serve to increase a sense of individuation and decrease a sense of belonging and identification (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Further, this process may occur outside the individual as groups may actively discredit and marginalize deviant members (Marques, Abrams, & Serôdio, 2001; Williams, 2001, 2007).

Importantly, the individual should typically try to eliminate feelings of EI produced by various short-term or situational influences. How do we reduce, “bury,” or “undo” experiences of EI? The primary mechanism is relational in nature (Fromm, 1963; Yalom, 1980). This can take the form of relationship with work (e.g., an artist becomes completely immersed in their craft; or a workaholic); orgiastic states (e.g., religious, sexual, or drug-induced); mergence or fusion with a group; or investment in interpersonal relationships (Yalom, 1980). However, people can also try to avoid feelings of EI by assuming that others share their internal states (e.g., Murray, Holmes, Bellavia, Griffin, & Dolderman, 2002) or their beliefs and attitudes (e.g., Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). Additionally, individuals may try to avoid isolation by changing their views to match those around them (e.g., Asch, 1951; Echterhoff et al., 2009). Perhaps in extreme examples, individuals may seek to fuse their identity with their groups, risking losing their sense of individuality (Swann, Jetten, Gómez, Whitehouse, & Bastian, 2012). In essence, following the logic of distinctiveness theories (e.g., Brewer, 1991; Snyder & Fromkin, 1977), EI serves as a differentiation cue motivating the individual to seek assimilation (H10). All of these hypotheses, although consistent with prior theory and research on social judgments and behavior, are in need of direct testing.

However, if these feelings remain unresolved, either because the situation becomes chronic (e.g., the war veteran is constantly around civilians who cannot understand) or there are repeated instances of feeling separate and disconnected (e.g., the socially anxious individual who cannot seem to accurately read social cues), the individual may begin to feel a chronic sense of EI (H11). This transition likely occurs via self-perception processes (Bem, 1972; Fazio, 1987) through which the individual seeks to explain their behavior and circumstances. In this case, the individual may adopt the perspective that they are different from others with a unique perspective that others do not understand.

2.2.2 Reactions and outcomes to trait existential isolation

In contrast to state EI, where some event or interaction makes one feel as though they have different experiences than other people, trait EI is a chronic and pervasive sense that one is alone in their experiences. Given its ever-present nature, individuals are less likely to try to actively avoid these feelings or even know how to do so. Rather, they are more likely to give into them, resulting in feelings of helplessness or hopelessness and withdrawal behaviors (H12).

Because humans rely on shared reality (Hardin & Higgins, 1996) and socially agreed upon norms to substantiate our cultural worldviews (e.g., Greenberg, Solomon, & Arndt, 2008), constant feelings of EI should make the individual feel vulnerable and have diminished need satisfaction (Vangelisti, 2001). The vulnerable individual, barring other defensive or buffering mechanisms, does not want to be hurt further, and thus is likely to distance themselves from a future possibility of discomfort (Vangelisti, Young, Carpenter-Theune, & Alexander, 2005). Since EI creates an uncomfortable state, situations in which EI is heightened should be particularly painful for those who chronically experience EI. Furthermore, the existentially isolated individual should have a low expectation of relationship repair (Richman & Leary, 2009). In general, these tendencies are consistent with the prediction that existentially isolated individuals should be more likely to withdraw from social interactions following rejection.

There is some initial evidence for this line of thinking. Pinel et al. (2017) found that trait EI was uncorrelated with the need to belong (Leary, Kelly, Cottrell, & Schreindorfer, 2013), which suggests that heightened feelings of EI are not associated with an increased need to belong. In contrast, Pinel et al., (2017) found that loneliness was positively correlated with a need to belong. There is a plethora of research connecting feelings of loneliness with increased desire for social connection (e.g., Gardner, Pickett, Jefferis, & Knowles, 2005) including the need to belong. Cacioppo et al. (2006) argued that the experience of loneliness “drives” individuals to seek fulfillment of social needs. Thus, if high trait EI individuals do not report greater need to belong, it suggests that they do not have the same increased desire to seek social connection that those experiencing other forms of isolation do. In the same study, Pinel et al. (2017) found that EI was positively correlated with alienation, which supports the notion that chronically existentially isolated individuals are more resigned to their situation (Riva, Montali, Wirth, Curioni, & Williams, 2017; Williams, 2009).

Other work (Pinel, Long, & Murdoch, 2018) has found that people high in trait EI have lower levels of egalitarianism, empathy, sense of community, and satisfied needs for relatedness compared to those low in trait EI. Using mediational analysis, the researchers found that a composite measure of basic needs mediates the relation between EI and egalitarianism, empathy, and sense of community. Generally, these data suggest high trait EI is associated with patterns of disengagement with others (feeling alienated, not needing to belong, less sense of community and empathy) and that unsatisfied basic needs (e.g., relatedness) may contribute to these tendencies.

Given that the initial state experiences of EI should result in attempts to reduce the feeling, those with high trait EI may have at first attempted to reduce these feelings but were unsuccessful. An unsuccessful attempt at connecting with others would reiterate the painful experience of EI and eventually cause the individual to give up trying to connect in order to avoid what may come to be seen as an unbridgeable gap.

When feeling existentially isolated becomes part of one's self-concept and an individual feels a general sense of separation or disconnect from others, the consequences also become more severe. Rather than in-the-moment need depletion, the individual should generally report lower well-being, unsatisfied needs, and should be more withdrawn from others (H13). Helm et al. (2018) found that trait EI was negatively correlated with self-esteem and with endorsement of communal values (e.g., trust, altruism, loyalty, and compassion). Pinel et al. (2017) found trait EI to be negatively correlated with extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience. Costello and Long (2014) found that trait EI was positively correlated with generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and self-concealment. Although these findings are correlational, taken together they suggest that the chronically existentially isolated individual has lower need satisfaction, tendencies that separate the individual from others, and does not endorse prosocial group-oriented values (H13).

It takes so little, so infinitely little, for a person to cross the border beyond which everything loses meaning: love, convictions, faith, history. Human life – and herein lies its secret – takes place in the immediate proximity of that border, even in direct contact with it; it is not miles away, but a fraction of an inch.

What keeps people on the preferred side of that border is feeling that their view of the world is validated by others. Existentialist thinkers argue that there is no objective meaning in the world (e.g., Camus, 1955; Heidegger, 1927). Without an objective truth to rely on, people turn to each other for meaning through their relationships and communities to create a sense of shared reality (Baumeister, 1991; Chiu & Hong, 2007; Hardin & Higgins, 1996; Sullivan, Kosloff, & Greenberg, 2012). A part of this process involves individuals feeling as though their personal perspectives are validated in social interactions (Swann, Stein-Seroussl, & Giesler, 1992). Feelings of EI thwart this process because the individual feels as though they have a unique perspective and that others do not, or cannot, understand their outlook.

One correlational study provided evidence for the link between EI and perceived meaning. Pinel and colleagues (Pinel, Long, Johnson, & Yawger, 2018) looked at the correlation between EI and several indices of meaning including the meaningfulness subscale of the Sense of Coherence Scale (Antonovsky, 1983), the Life Regard Index (Battista & Almond, 1973), which measures perceptions of one's life as meaningful; and the Purpose in Life Test (Crumbaugh, 1968). For all the three measures of sense of meaning, these researchers found significant negative correlations with EI. These findings point to the meaning implications of EI and corroborate Yalom's (1980) writings, in which he maintains that struggles with EI can increase other existential problems, such as lack of meaning.

In another study that highlights EI's implications for meaning, the researchers explored the implications of EI for targets of stigma (Long, Pinel, & Murdoch, 2018). Participants who identified as Black and who varied in their levels of EI rated the degree to which they perceived three ambiguously racist scenarios to reflect racism; the participants also indicated how certain they were of their judgments (Long et al., 2018). As one would predict based on the arguments we have articulated here, compared to participants low in EI, those high in EI expressed significantly greater uncertainty in their judgments as to whether the scenarios actually depicted acts of racism. This finding again supports the idea that the existentially isolated are less confident in their perceptions of reality, which should undermine meaning.

According to our model, the existentially isolated individual should feel separated from others and may have psychological tendencies that make connecting with others more difficult. These tendencies may develop into diminished group identities at a global level. In contrast to diminished specific in-group identity as a consequence of state EI, individuals with trait EI should feel less identity to most of their social groups (H13). Social group identifications are important bases of meaning. They afford meaning by providing validation for one's meaning structures (Hogg & Mahajan, 2018; Marques & Paez, 1994; Marques & Yzerbyt, 1988). To the extent that EI challenges people's ability to acquire and maintain meaning, someone high in EI, who feels as though no one can validate his or her unique experience of reality, should therefore not derive the same meaning from identification with his or her social groups generally.

Correlational studies provide preliminary evidence for this account (Helm, et al., 2018). In a large sample of undergraduates, the researchers measured trait EI and the importance participants placed on both their American identity and their college identity. EI correlated negatively with both identity measures. Related research by Park and Pinel (2018) examined EI in South Korea and found a significant negative correlation between EI and both levels of nationalism and satisfaction with South Korea.

From a terror management theory perspective, cultural groups, such as those based on national or college identity, provide a meaningful base from which one can build self-esteem and psychological security (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1992). Consequently, threats to people's social identities increase the accessibility of death-related thought (e.g., Arndt, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski, & Simon, 1997). To the extent that people high in EI do not identify with these groups, they also do not benefit from the protective meaning that such identification provides.

As noted previously, participants primed with feelings of EI reported higher death-thought accessibility than those primed with control topics (Helm, Lifshin, Chau, et al., 2018). In a separate study, these researchers also found that trait EI positively correlates with high dispositional death-thought accessibility (Hayes et al., 2010). Dispositional death-thought accessibility refers to how accessible death thoughts are without the presence of a threat and is indicative of a “relatively weak or unstable anxiety buffer” (Hayes et al., 2010, p. 710). Finding that EI is correlated with both lower in-group identity and higher dispositional death-thought accessibility, and that experimental manipulations of EI increase death-thought accessibility, supports the notion that those who are existentially isolated have less certain bases of meaning.

Trait EI should also have consequences for mental health. In particular, EI should be particularly problematic for mental health because a meaningful view of the world and positive social connections are valuable resources for sustaining mental health (H13). There is some preliminary evidence to support these connections. As mentioned previously, Costello and Long (2014) found that trait EI was positively correlated with general and social anxiety.

A more recent set of studies has focused on depression. Helm, Medrano, Greenberg, and Allen (2018) predicted that because trait EI undermines a meaningful view of reality, it is associated with higher depression and higher suicide ideation among college undergraduates. In support of their hypothesis, the researchers found that trait EI predicted higher depression and suicide ideation. Further, they found that EI interacted with loneliness to predict greater depression and suicide ideation. Although not initially predicted, this interaction has been found in three consecutive large samples of undergraduates. The individual who is both lonely (i.e., feels like they do not have the desired social connections) and existentially isolated (i.e., feeling unable to connect with others and has withdrawing from social situations) is particularly susceptible to feelings of depression and suicide ideation. This may be because the person who still wants social connections but at the same time has given up on such possibilities is in an impossible dilemma, driving them toward despair. Although these studies suggest that EI may be quite consequential for mental health, additional research is needed to understand possible causal relationships among these constructs.

2.3 Other potential moderators of EI effects

Although feelings of trait EI hinder need satisfaction in a number of ways, particularly needs of relatedness and connection, need for meaning, need for shared reality, and need for validation of self-esteem, trait EI should not affect everyone equally. The evidence that has been reviewed above suggests moderation by loneliness—it is the high EI people who are also lonely who are most troubled (H14). Or, put differently, high EI people who are not lonely may have somehow accepted their EI and be functioning well. Loneliness should also moderate state EI processes, such that those with higher loneliness should be more susceptible to feeling state EI, and should be more likely to experience the negative outcomes related to state EI (H15). Other psychological constructs that help buffer individuals from anxiety may also moderate the impact of EI. We refer to anxiety buffers in particular because these protective mechanisms serve to help the individual maintain psychological equanimity (Pyszczynski & Kesebir, 2011), and these same mechanisms should also help buffer the individual against EI (H16). For example, self-esteem functions to buffer against and ameliorate anxiety (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1992), and numerous studies have found that high self-esteem is associated with greater mental and physical health (e.g., Antonucci & Jackson, 1983; Kernis, 2005). In terms of EI, those with high and stable self-esteem should be more self-assured and less defensive (Kernis, 2005). Thus, when a situation increases feelings of EI, high self-esteem individuals should more easily be able to rationalize, justify, or let go of the negative affect. For example, a new employee on her first day of work tries to tell a joke to her coworkers and nobody laughs. Although likely uncomfortable for everyone, someone with low self-esteem should be more sensitive to this situation and feel disconnected from her coworkers. In contrast, someone with high self-esteem should be less affected by this situation and have an easier time rationalizing the situation.

Additionally, reactions to state EI may be moderated by the levels of trait EI (H17). When an individual has incorporated EI into their self-concept and has a general sense that they have a different subjective experience than others, it leaves them more vulnerable to situations that may elicit EI. For the same reason that those high in trait EI withdraw from social situations, situations that make salient the discrepancy between the self and others may be particularly painful. In their studies examining the relationship between death-thought accessibility and EI, Helm, Lifshin, Chau, et al. (2018) found that the EI prime was particularly powerful for those already high in EI. This makes sense given that the high trait EI individual should have numerous previous experiences in which they felt disconnected from others to draw upon. Thus, each additional new experience can easily trigger memories and feelings that further perpetuate their EI.

2.4 Causal paths

Of course, much of the evidence discussed above is correlational, and we can interpret it in multiple ways. Perhaps people high in EI—who do not feel validated by others—become alienated from mainstream social identities and cultural institutions, which results in diminished importance of some group identities. On the other hand, perhaps the inability to form or sustain such social identifications causes people to experience elevated levels of EI. We find both of these possibilities to be plausible. However, our model specifies that particular circumstances (e.g., specific event, relationship with a group, attachment orientation) create opportunities to experience EI. Once someone is experiencing EI, it could create a cycle in which the individual creates situations that perpetuate EI. However, these causal paths have yet to be fully explored. We suggest that future studies consider utilizing longitudinal designs with cross-lagged panel analyses in order to begin parsing apart the directionality of these relationships.

Another important hypothesis that warrants investigation is how high trait EI people respond to rejection. Prior research (Gardner et al., 2005; Richman & Leary, 2009) suggests that people in general, and lonely people in particular, react to rejection with efforts to enhance social connections. But the present model proposes that high trait EI people should respond to rejection with withdrawal instead (H12). Bringing in high and low EI people and having some of them experience a rejection would help test this idea.

2.5 Possible avenues for ameliorating existential isolation

Our model and research to date suggest that experiences of EI can become a general, stable outlook that hinders well-being. And approaches to the problem of loneliness, such a social skills training and providing better opportunities for cultivating relationships (e.g., Rook, 1984), are not as likely to work with high EI people. But a line of research regarding I-sharing provides a glimmer of optimism (Pinel et al., 2004; Pinel, Long, Landau, Alexander, & Pyszczynski, 2006; Pinel et al., 2010; Pinel & Long, 2012; Pinel, Bernecker, & Rampy, 2015; Pinel et al., 2018). I-sharing refers to those moments when people believe they have the same internal, in-the-moment experience as one or more other people. When people I-share, at least for that I-sharing moment, they experience a moment of existential connection. Not surprisingly then, people high in EI show strong levels of liking for I-sharers. This is true regardless of whether the EI is of the state variety (Pinel et al., 2006) or of the trait variety (Pinel & Long, 2012). Moreover, people high in EI like I-sharers precisely because I-sharers make them feel subjectively similar (i.e., existentially connected; Pinel et al., 2018). This literature suggests that experiences of I-sharing might shift people toward a greater sense of subjective similarity to others and thus lower trait EI.

Of course, for those high in trait EI it would take a lot more than a single or a small set of I-sharing moments to shift their outlook. But a relationship in which I-sharing plays a central role might do the trick. Indeed, numerous thinkers (e.g., Buber, 1947; Fromm, 1963; Yalom, 1980) have argued that what Buber (1970) would called an “I-Thou” relationship is the best hope for reducing high EI. Contrasted with an “I-It” relationship, which is one in which a person is in a relationship for a specific purpose, an “I-Thou” relationship is a mutual relationship marked by empathy, perspective taking, and reciprocity. This relationship is posited to be best suited to alleviate feelings of EI because the relationship involves validating the subjective experiences of the individual. Because high EI is associated with an avoidant attachment style, it would be no easy task to facilitate such a validating I-Thou relationship in high EI people, but some hope can be found in evidence that, although attachment style is moderately stable over time, people do shift in their attachment styles over a four-year period (Kirkpatrick & Hazan, 1994). Perhaps future research could thus focus on how to break down the high EI person's avoidant tendencies that block the development of validating, secure relationships, and thereby bring their level of EI down.

3 CONCLUSION

We have proposed a model of EI that has significant implications for psychological well-being, adjustment, and mental health. Although empirical research on this construct is in its early stages, we have reviewed data that fit the model and that point to the promise of pursuing the connection between both state and trait EI and other psychological constructs. EI predicts lower certainty, lower levels of basic need satisfaction, higher dispositional death-thought accessibility, lower purpose in life, and lower meaningfulness. These correlations are consistent with the notion that EI makes people more vulnerable to feelings of maladjustment. Indeed, EI correlates positively with general anxiety, social anxiety, and depression. Data also consistently show that existentially isolated individuals tend not to identify with social groups that would otherwise afford them with a sense of meaning, and this is true for participants sampled in both the United States and in South Korea. On perhaps a more positive note, existential isolation does make people who I-share with us more attractive, and this can suggest one route to helping the existentially isolated.

The State Trait Existential Isolation Model posits a variety of hypotheses that are ripe for further investigation. Researchers have given a lot of attention to other forms of interpersonal isolation and have found that they go hand in hand with a host of disturbing consequences, including depression (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010), suicide (Gini & Espelage, 2014), aggression (DeWall, Twenge, Gitter, & Baumeister, 2009; Gaertner, Iuzzini, & O'Mara, 2008; Twenge, Baumeister, Tice, & Stucke, 2001), and homicide (Leary, Kowalski, Smith, & Phillips, 2003). We believe the current model offers a variety of avenues for research to build a more nuanced understanding of existential isolation, and this will clarify the role of EI in these kinds of significant problems as well. Once we grasp how the distinct varieties of interpersonal isolation account for their many negative consequences, we will be in a much better position to develop therapeutic and social approaches to remedying these problems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was not supported by any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.