Extending the benefits of intergroup contact beyond attitudes: When does intergroup contact predict greater collective action support?

Abstract

It is well established that intergroup contact is associated with more positive intergroup attitudes. Associations between intergroup contact and active outcomes more closely tied to social change are less reliable. Whereas some research demonstrates that intergroup contact can promote social change, other research paradoxically demonstrates that intergroup contact can undermine social change. We review the literature with the goal of explaining this apparent paradox. We present a model for understanding when intergroup contact can contribute positively to active outcomes while still predicting positive intergroup attitudes. Specifically, upon reaching a contact threshold whereby outgroup members are viewed as potential friends, having cross-group friendship that involves recognition of group differences and condemnation of group inequality may promote positive intergroup attitudes as well as positive intergroup behavior, policy support, and collective action aimed at reducing group inequality. We propose that a cross-group friendship involving these qualities will promote ambivalence toward the advantaged group, which will be beneficial in terms of social change related outcomes. It is critical for future research to examine the conditions under which cross-group friendships involving these qualities are formed and maintained.

1 INTRODUCTION

Decades of research has established a consistent negative relationship between intergroup contact—social interaction between members of different groups (e.g., nationality, racial, or religious groups)—and intergroup attitudes (e.g., Dovidio, Love, Schellhaas, & Hewstone, 2017; Hewstone & Swart, 2011; Hodson & Hewstone, 2013a; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; Pettigrew, Tropp, Wagner, & Christ, 2011). Specifically, it is well established that the more contact one has with outgroup members the more positive one's attitudes are toward that outgroup (and some other outgroups, Pettigrew, 2009). This is explained by processes such as lower intergroup anxiety, greater empathy toward the outgroup, and more knowledge about the outgroup (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). Whereas there is a reliable association between more intergroup contact and less biased attitudes, associations between intergroup contact and outcomes such as behavior toward the outgroup (e.g., Van Laar, Levin, Sinclair, & Sidanius, 2005), policy support (e.g., Dixon, Durrheim, et al., 2010), and collective action (e.g., Cakal, Hewstone, Schwär & Heath, 2011), are less consistent. Moreover, in cases when these variables are examined, intergroup contact sometimes predicts detrimental outcomes (e.g., Saguy, Tausch, Dovidio, & Pratto, 2009; Wright & Lubensky, 2008). This presents a paradox: intergroup contact is associated with less negative (and more positive) intergroup attitudes, but can do little good or even impose damage when it comes to practical outcomes in intergroup relations (i.e., behavior, policy support, and collective action). In the current paper, we unpack this apparent paradox and provide a conceptual model for understanding how the effects of contact can be extended beyond attitudes to these more active outcomes.

2 THE CONTACT THRESHOLD

Although much of the research on intergroup contact is cross-sectional (see MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), and the relationship between intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes is bidirectional (Binder et al., 2009), intergroup contact is generally considered as a predictor of intergroup attitudes and related constructs such as intergroup anxiety, intergroup behavior, and collective action support. Here we discuss a paradox on the outcome end of these relationships (i.e., relating to bias-relevant outcome variables). Previous work (i.e., MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015), however, has recognized a paradox at the predictor end of these relationships (i.e., relating to contact-relevant predictor variables). Specifically, not only is there a sizable literature documenting that intergroup contact is associated with lower intergroup anxiety and more positive intergroup attitudes (e.g., Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), but it is also well established that interactions between members of different social groups are associated with stress, anxiety, and avoidance of outgroup members (e.g., Blascovich, Barry Mendes, Hunter, Lickel, & Kowai-Bell, 2001; Hyers & Swim, 1998; Littleford, Wright, & Sayoc-Parial, 2005; Shelton, 2003; Shelton, Dovidio, Hebl, & Richeson, 2009; Shelton, Richeson, & Vorauer, 2006; Trawalter, Richeson, & Shelton, 2009). These findings, on the surface, appear inconsistent given that both of these literatures examine the same topic: social interactions between members of different groups.

As MacInnis and Page-Gould (2015) discuss, it is likely that methodological differences account for these discrepant findings and that both sets of findings are accurate but focus on different levels of the same phenomenon: the intergroup interaction findings focus on shorter term intergroup contact (e.g., one's first intergroup interactions), whereas the intergroup contact findings focus on longer term intergroup contact (e.g., one's lifetime history of intergroup contact). That is, initial experiences interacting with outgroup members are anxiety-provoking and lead to outgroup avoidance, but after a number of positive intergroup interactions take place, intergroup interactions generally become more positive and predictive of more positive intergroup attitudes. This critical number of intergroup interactions, which is influenced by several factors, MacInnis and Page-Gould label the “contact threshold.” Upon reaching the contact threshold, interactions with outgroup members begin to have a beneficial influence on intergroup attitudes (i.e., evaluations). Preliminary evidence supports the asymptotic relationship between intergroup contact and intergroup bias proposed by MacInnis and Page-Gould (i.e., that the relationship between intergroup contact and bias is initially variable but becomes more reliable and linear—with more contact associated with less bias—as interactions increase, I. D. Miller, MacInnis, & Page-Gould, 2017; Page-Gould, MacInnis, & Sharples, 2018). Whereas the focus of MacInnis and Page-Gould's model concerns contact quantity, contact quantity and contact quality are strongly intertwined, and quality can predict bias more strongly than quantity (Barlow et al., 2012). As such, the rate with which one reaches the contact threshold is likely to be heavily influenced by contact quality. High contact quantity and contact quality are likely to result in the fastest reaching of the threshold, but the threshold can be reached with high levels of one or the other (see MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015).

An important avenue for future research is to further explore the contact threshold and the best means to reach it (MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015). However, with the goal of overall intergroup harmony, this is only a starting point. To the best of the field's knowledge, even upon reaching the contact threshold the positive effects of intergroup contact are largely limited to intergroup attitudes and evaluations. How might reaching the contact threshold influence collective action, for example? We encourage that attention be devoted to the outcome variable end of the relationship. A comprehensive bias reduction strategy would influence behavior, collective action, and policy support as well as intergroup attitudes, for both advantaged and disadvantaged group members. Is it possible for intergroup contact to serve this function? Below, we review the existing literature on intergroup contact and each of these outcomes, and then offer a conceptual model to synthesize seeming contradictions in this literature.

3 INTERGROUP CONTACT AND INTERGROUP ATTITUDES

A highly valued and widely cited meta-analysis of 516 studies demonstrated a small but reliable negative relationship between intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes (mean r = —.21, Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). This relationship is relatively consistent across various group domains including ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, mental illness, and religion. In the years following this meta-analysis, numerous examinations have revealed relationships of similar magnitude between intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes (e.g., Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014; Lemmer & Wagner, 2015). Intergroup contact involving conditions identified by Allport (1954) as critical for reducing prejudice—cooperation, common goals, equal group status, and support from authorities—is associated more strongly with less negative intergroup attitudes (mean r = −.28, Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). In addition to intergroup contact generally, a more intimate form of intergroup contact—intergroup friendship, which is typically considered to involve at least the first three of Allport's (1954) optimal contact conditions—is also associated with less negative intergroup attitudes, with a somewhat larger effect size (r = −.25, Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; r = .31, Davies, Tropp, Arthur, Pettigrew, & Wright, 2011).

Despite this consistent negative relationship, two major caveats are in order. First, the effects of intergroup contact are stronger and more consistent for the advantaged than disadvantaged group (Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005). Although a limitation, advantaged group members are typically the perpetrators of prejudice (and disadvantaged group members the victims of prejudice), so this is where attention should be focused in terms of improving intergroup attitudes. Promisingly, intergroup friendship has prejudice-reducing effects for both advantaged and disadvantaged group members (Davies et al., 2011). The second caveat is that intergroup contact quality matters. Whereas positive intergroup contact predicts less negative intergroup attitudes, negative contact predicts more negative intergroup attitudes, with the latter effect being even stronger than the former (Barlow et al., 2012). Fortunately, experiencing positive or high quantity intergroup contact can buffer the effects of negative contact on heightened prejudice (Paolini et al., 2014). Despite these caveats, intergroup contact is generally considered one of the best means of improving intergroup attitudes (e.g., Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014).

4 INTERGROUP CONTACT AND BEHAVIOR

Compared to attitudes, the influence of intergroup contact on intergroup behavior is less consistent. In line with modern conceptualizations of prejudice, attitudes toward outgroup members have become more positive over time, but behaviors toward outgroup members have remained largely unchanged (e.g., Dovidio & Gaertner, 2000, 2004; Quillian, Pager, Hexel, & Midtbøen, 2017). Avoidance of outgroup members (even when desire for intergroup contact is expressed; Shelton & Richeson, 2005) is the norm, segregation is common in settings such as cafeterias, beaches, and lectures (Clack, Dixon, & Tredoux, 2005; Dixon & Durrheim, 2003; Koen & Durrheim, 2010), and racial discrimination in hiring remains prevalent (Quillian et al., 2017). It appears that relative to negative intergroup attitudes, negative intergroup behaviors (e.g., avoidance; discrimination) are more persistent.

Compared to studies examining attitude outcomes of intergroup contact, studies examining behavioral outcomes of intergroup contact are relatively rare. This may be because behavior is more difficult to assess than attitudes. Alternatively, given the strong historical bias of journals accepting predominantly significant results, this might reflect a file drawer effect. Yet there are some studies examining the influence of intergroup contact on behavior. Johnson and Johnson (1981) found that children who participated in an intergroup contact intervention later reported more cross-group friends and were observed engaging in more cross-group interactions. Rooney-Rebeck and Leonard (1986) observed a similar pattern but their results were specific to first-grade children only (first- and third-grade children were examined). Van Laar et al. (2005) demonstrated reliable evidence that contact with an interethnic roommate results in less negative attitudes, but the influence of roommate contact on behavior (as measured by heterogeneity of friendships and interethnic dating) was weaker. Having a cross-ethnic roommate was not associated with more friendship heterogeneity or interethnic dating in the first-year of university. Having more cross-ethnic roommates was, however, associated with more interethnic dating (but again not friendship heterogeneity) by the fourth year of university. Additionally, making a cross-group friend has been found to predict initiating more intergroup interactions, but only among those higher in implicit prejudice (Page-Gould, Mendoza-Denton, & Tropp, 2008), and intergroup contact can predict greater willingness to hire an outgroup member (Fasbender & Wang, 2017), although actual hiring has not been examined. With regard to seating choice, intergroup contact has been associated with less segregated seating patterns for both youth in Northern Ireland (McKeown, Cairns, Stringer & Rae, 2012) and children in racially diverse schools (McKeown, Williams & Pauker, 2017). However, although intergroup contact predicts greater tendency to sit next to an outgroup member these less segregated seating choices do not seem to last over time. Overall, the relationship between intergroup contact and intergroup behavior is far less reliable and understood than the relationship between intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes.

5 INTERGROUP CONTACT AND POLICY SUPPORT

The relationship between intergroup contact and policy support has also been understudied. Although it is often presumed that the positive effects of intergroup contact on intergroup attitudes generalize to other relevant outcomes such as policy, this has not been reliably established (Dixon, Levine, Reicher, & Durrheim, 2012). In fact, a sizable proportion of White Americans (39%) holding positive attitudes toward Black Americans were found to be against policies promoting racial equality in housing, education, and employment (Jackman, 1994). Upon uncovering a disconnect whereby intergroup contact predicted more liking and acceptance of Blacks by Whites but not support for policies intended to reduce inequality between Blacks and Whites, Jackman and Crane (1986) implored researchers to focus more attention on policy support. Relative to the multitude of studies examining intergroup contact as it predicts attitude outcomes, however, only a handful of studies have examined the relationship between intergroup contact and the support of policies benefitting disadvantaged groups. In a few promising examples, those knowing someone with AIDS were more supportive of those living with AIDS continuing to work (Gerbet, Sumser, & Maguire, 1991); White South Africans having contact with Blacks were less opposed to compensatory and preferential policies in favor of Blacks (Dixon, Durrheim et al., 2010); a reanalysis of Jackman and Crane's (1986) work found that Whites having (vs. not having) close ties with Blacks indeed support policies benefitting Blacks (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2011); and interacting with a transgendered person predicted support for policies benefitting transgendered people (Brockman & Kalla, 2016).

On the other hand, other research shows that when White students interacted (via video) with a Black confederate and common group membership (university student identity) was salient (vs. dual identity, Black identity, or individual identity), racial attitudes were relatively positive but support for campus policies encouraging multiculturalism was relatively low and support for campus policies disregarding race was relatively high (Dovidio, Gaertner, Shnabel, Saguy & Johnson, 2010). Additionally, when examining the contact-policy support association among a disadvantaged group—Black South Africans—positive intergroup contact with Whites was associated with less support for policies aimed at reducing racial inequality (Dixon, Durrheim, & Tredoux, 2007). Similarly, contact between White New Zealanders and Maoris predicted lower support of policies aimed at reducing racial injustice among Maori (Sengupta & Sibley, 2013). It seems that in some circumstances, improving intergroup attitudes through intergroup contact can ironically reduce endorsement of policies supporting group equality (Dixon et al., 2012), even (or particularly) among the disadvantaged group. Yet in a multi-level investigation, disadvantaged group members supported anti-discrimination policies more when living in areas with more positive intergroup contact (Kauff, Green, Schmid, Hewstone, & Christ, 2016). Clearly, more research is needed in this domain. Even if the relationship between intergroup contact and policy support were more clear, however, the process of translating research results into effective policy remains extremely challenging (Pettigrew & Hewstone, 2017).

6 INTERGROUP CONTACT AND COLLECTIVE ACTION

Whereas positive intergroup attitudes, positive intergroup behavior, and the support of policies in favor of group equality are important contributors to promoting positive relations between groups, collective action is critical to stimulate the type of broad scale social change needed to achieve intergroup harmony and/or equality. Although intergroup behavior (e.g., [lack of] discrimination) and policy support are often considered forms of collective action, we consider collective action conceptually distinct in its own right. Collective action in the current context refers to action by disadvantaged group members (and/or advantaged group member allies) aimed at reducing injustice/inequality and changing the status quo (Dixon et al., 2012). Akin to the relationships between intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes, intergroup behavior, or policy support, the relationship between intergroup contact and collective action varies depending on whether the disadvantaged or advantaged group perspective is examined. Current evidence suggests that the influence of intergroup contact on collective action and collective action support is negative for disadvantaged group members (e.g., Cakal et al., 2011; Saguy, Shchory-Eyal, Hasan-Aslih, Sobol, & Dovidio, 2017; Tropp, Hawi, Van Laar, & Levin, 2012) but positive for advantaged group members (e.g., Cakal et al., 2011; Fingerhut, 2011; Vezzali, Adrighetto, Capozza, Di Bernardo, & Saguay, 2017). That is, intergroup contact is generally associated with lower collective action participation and support for disadvantaged group members, but heightened collective action participation and support for advantaged group members.

Why might this be the case? It has been argued that intergroup contact can produce a “sedative effect” whereby contact reduces the motivation of disadvantaged group members to participate in collective action (Cakal et al., 2011). Indeed, more intergroup contact predicts lower collective action tendencies among Israeli Arabs, Black South Africans, Black Americans, and Latino Americans (Cakal et al., 2011; Dixon et al., 2012; Saguy et al., 2017; Tropp et al., 2012). In general, it is recognized that some of the very benefits of intergroup contact (e.g., more positive intergroup attitudes, development of a common ingroup identity) undermine collective action among disadvantaged group members. Feeling positively toward the advantaged group and perceiving that intergroup relations are fair serves to decrease collective action motivation (e.g., Becker & Tauch, 2015; Dovidio, Gaertner, Ufkes, Saguy, & Pearson, 2016; McKeown & Dixon, 2017; Wright & Lubensky, 2008). On the other hand, intergroup contact can increase perceptions of group relative deprivation among disadvantaged group members, that is, increase awareness of what the disadvantaged group is deprived of relative to the advantaged group and greater recognition of the inequality that exists between groups. Whereas intergroup contact often reduces the perceptions of discrimination among disadvantaged group members (e.g., Dixon, Tropp et al., 2010), group relative deprivation can increase disadvantaged group members' perceptions of group discrimination (Poore et al., 2002). Although the association between group relative deprivation arising from intergroup contact and collective action has not been examined, perceptions of discrimination can be a precursor to collective action support/participation (McKeown & Dixon, 2017). And, in general, relative deprivation can be associated with heightened collective action (Smith, Pettigrew, Pippin, & Bialosiewicz, 2012). It is possible that contact promoting heightened perceptions of relative group deprivation among disadvantaged group members (and hence heightened perceptions of discrimination) is relatively more negative in valence, whereas contact that undermines collective action among disadvantaged group members is relatively more positive in valence. In a recent investigation, Reimer et al. (2017) found that negative but not positive intergroup contact promoted sexual minority students' involvement in collective action. Thus, the typical form of intergroup contact examined by researchers—intergroup contact aimed at promoting positive intergroup attitudes—may exert a negative impact on collective action engagement for disadvantaged groups.

For advantaged group members, however, intergroup contact tends to promote collective action engagement. Whereas Cakal et al. (2011) found that intergroup contact decreased collective action among Black South Africans, it increased support for collective action among White South Africans. Intergroup contact has also increased motivation to participate in collective action for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgendered (LGBT) community among heterosexuals (Fingerhut, 2011). Cakal et al. (2011) and Fingerhut (2011) examined positive intergroup contact. Similarly—but contrary to their findings for disadvantaged groups—Reimer et al. (2017) found that only positive (and not negative) intergroup contact promoted LGBT activism among heterosexuals. Consistent with this, when group differences are recognized, and when contact involves repeated positive interactions (consistent with reaching a contact threshold, see MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015), intergroup contact is associated with heightened collective action motivation among advantaged group members (Vezzali et al., 2017).

Arguably, learning that the association between intergroup contact and lower prejudice is more reliable for advantaged than disadvantaged group members is not overly concerning given that prejudice held by advantaged group members is that in greatest need of remedy. When it comes to collective action, however, the discrepancy between disadvantaged and advantaged groups is considerably more problematic and consequential. In the interest of positive intergroup relations, collective action support/participation by both advantaged and disadvantaged group members is ideal. Indeed, participation in collective action by advantaged group members reduces advantaged group members' desire to defend the discriminatory status quo and promotes beliefs among the disadvantaged group that collective action may actually promote social change (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2013). But, participation in collective action by those actually experiencing the injustice is critical. Even the best intentioned advantaged group members cannot fully understand the experience of disadvantaged group members (Bilewicz, 2012), nor attain sufficient motivation to engage in action. Thus, it is necessary to resolve these discrepant findings and identify conditions under which intergroup contact can promote collective action support and participation among both advantaged and disadvantaged groups.

7 THE MIXED OUTCOMES OF INTERGROUP CONTACT: WHY DOES THIS PARADOX EXIST?

Upon reaching a contact threshold as identified by MacInnis and Page-Gould (2015), intergroup contact produces largely positive attitudinal outcomes in the form of reduced prejudice. As demonstrated above, there is growing evidence supporting this proposition. There is relatively less research on the influence of intergroup contact on intergroup behavior, policy support, or collective action support/participation, and existing research shows unclear and—under certain circumstances—negative outcomes. Although prejudice reduction is important, these more active outcomes are also essential. Positive attitudes in the absence of positive behavior, policy support, or collective action may mean failing to extend rights to these groups, upholding the status quo, and the perpetuation of inequality, even if unintended. Why does this paradox at the dependent variable end of the intergroup contact–intergroup relations relationship exist? Below we discuss several potential reasons.

First, following intergroup contact theory (Allport, 1954) individual prejudice scores are the dominant outcome assessed in intergroup contact literature. The focus of this literature concerns how intergroup contact reduces personal prejudice and how to strengthen this relationship. It was originally proposed that collective reduction in personal prejudice was the path to social change (Allport, 1954). Of course, focusing mainly on personal prejudices is limited and valid arguments have been made to expand the range of outcomes examined (e.g., Dixon, Durrheim, & Tredoux, 2005), but progress in this regard is slow. There may be practical concerns given that these outcomes can be more difficult to assess than self-report attitudes. There may also exist a large file drawer of studies assessing these other outcomes, although this is speculation. Regardless, the paradox may exist because there simply is not enough research on outcomes of intergroup contact beyond attitudes to understand the actual relationships.

Another recognized limitation is that intergroup contact as typically studied might not emulate “real world” contact (Dixon et al., 2005). High quality intergroup contact—and especially interracial contact—is not common. Perhaps, the relationship between intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes is not as positive as the literature portrays. It is challenging for psychology researchers to assess intergroup contact as it actually unfolds in real life; it may not be possible for intergroup contact measures to fully capture the complexities of human relationships. Perhaps it is only the contact experiences tapped by common contact measures or contact that takes place under well-controlled laboratory conditions that reliably predicts reduced prejudice.

It is also possible that this paradox, whereby intergroup contact is associated with more positive intergroup attitudes but does little for outcomes more closely tied to social change, is not really a paradox at all, especially with regard to outcomes among disadvantaged group members. That is, perhaps these findings should appear inconsistent. It may be that negative attitudes toward the advantaged group are a necessary precursor for policy support and collective action among disadvantaged group members. That is, more positive attitudes toward the advantaged group as a result of intergroup contact removes this necessary precursor and as such undermines disadvantaged group members' policy support and collective action (Dixon, Durrheim et al., 2010). Indeed, support of policies aimed at reducing inequality and collective action against the status quo are more likely when the disadvantaged group feels negatively toward the advantaged group (Becker & Tauch, 2015; Wright & Baray, 2012; Wright & Lubensky, 2008). Consistent with the literature on collective action, it may be conflict (vs. peace) that is necessary for collective action (Wright & Baray, 2012; Wright & Lubensky, 2008). While promoting positive intergroup attitudes, intergroup contact can enhance (inaccurate) expectations that the disadvantaged group will be treated fairly by the advantaged group (Saguy et al., 2009), promote a common ingroup identity (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000) reduce anger toward the outgroup (Tausch, Saguay, & Bryson, 2015) and reduce perceptions of discrimination (Dixon, Tropp et al., 2010). All of these outcomes can reduce perceptions of group inequality and hence reduce motivation to challenge group inequality (Dixon et al., 2012; Saguy et al., 2009; Ufkes, Calcagno, Glasford & Dovidio, 2016; Ufkes, Dovidio & Tel, 2015; van Zomeren, Postmes, & Spears, 2008).

So, is the answer to stimulate more positive contact (and positive attitudes) for advantaged group members but more negative contact (and negative attitudes) for disadvantaged group members? Or should the field be moving away from examining intergroup attitudes and focus more on outcomes more closely tied to social change? We argue that the answer to both of these questions is no. We advise that the field be cautious about encouraging negativity and conflict (see Hewstone, Swart, & Hodson, 2012). And we propose that it may be that what happens during intergroup contact that accounts for discrepant findings depending on intergroup contact outcome assessed. It may be that it is possible for positive intergroup contact to exert positive outcomes on intergroup attitudes, intergroup behavior, policy support, and collective action among both advantaged and disadvantaged groups, but this is only possible under certain contact conditions. We expand on this potential below.

8 HOW CAN THE PARADOX BE RESOLVED?

We propose that this paradox can be reconciled, and we provide a visual depiction in Figure 1 that is explained in detail below. The dominant design of studies on intergroup contact is cross-sectional, asking about a person's history of contact and examining bias-relevant outcomes (MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Many of these studies do not assess the content of the interactions that make up the contact (Harwood, Hewstone, Paolini, & Voci, 2005), and studies that manipulate interaction content often involve contact that focuses on commonalities between group members (e.g., Gaertner & Dovidio, 2009). Although focusing on commonalities can positively influence intergroup attitudes (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2009), political activities that serve to maintain inequality likely remain unchanged, as is often the case when more positive intergroup attitudes are induced (Dixon et al., 2005; Jackman & Crane, 1986). Focusing on intergroup differences and recognizing group inequality may be key to extending these positive outcomes beyond attitudes to more active outcomes such as policy support and collective action participation for both advantaged and disadvantaged group members. This is consistent with the mutual intergroup differentiation approach to intergroup contact, a theoretical perspective suggesting that intergroup contact is most successful when group membership categories are salient (Brown & Hewstone, 2005), and contrasts with the personalization approach to intergroup contact which argues for de-emphasizing group categories during contact (Brewer & Miller, 1984, 1988). It may be that negative contact motivates disadvantaged group members to engage in collective action and positive contact de-motivates such action (as per Reimer et al., 2017) because the former draws attention to group inequality and the latter draws attention away from group inequality. We posit that positive contact with a focus on group inequality will result in the most positive outcomes. Emerging research supports placing emphasis on group memberships and group differences.

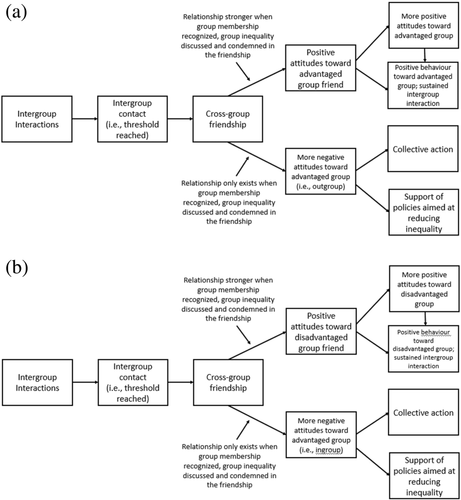

(a) Proposed pattern of relations for disadvantaged group members. (b) Proposed pattern of relations for advantaged group members

For example, among disadvantaged group members, focusing on group commonalities predicts reduced collective action (Ufkes et al., 2015), and emphasizing group differences (vs. commonalities) predicts potential antecedents of collective action engagement such as heightened attention to group inequalities and reduced expectations of outgroup fairness (Saguy et al., 2009) and social change motivation (Glasford & Dovidio, 2011). Becker, Wright, Lubensky, and Zhou (2013) examined intergroup contact where the advantaged group member either communicated that group inequality was legitimate, illegitimate, or did not mention their thoughts on group inequality. They found that this intergroup contact positively influenced disadvantaged group members' intergroup attitudes. However, collective action intentions and engagement were reduced when the advantaged group member viewed group inequality as legitimate or did not discuss it (vs. control) and were not reduced (vs. control) when the advantaged group member viewed group inequality as illegitimate. Although all scenarios in this study involved a recognition of group membership (and hence group differences), recognition of group inequality had the most positive outcomes for collective action. When colourblind perspectives—which, by definition, downplay group differences in the domain of race—are held by advantaged group members, they promote negative intergroup outcomes relative to perspectives recognizing group differences. For example, colourblind perspectives have been associated with increased racial bias (Richeson & Nussbaum, 2004) or less effective responding to racial inequality (Apfelbaum, Pauker, Sommers, & Ambady, 2010), relative to value diversity or multiculturalism perspectives, respectively. Additionally, for advantaged group members, recent evidence demonstrates that a focus on group differences (vs. commonalities) during intergroup interactions promotes greater motivation for social change, but this finding is specific to interactions that are part of repeated positive intergroup contact (Vezzali et al., 2017).

The important boundary condition identified by Vezzali et al. (2017) demonstrates that we must consider these findings supporting a focus on group differences, and recognizing group inequalities, in light of the paradox at the predictor end of the contact–bias relationship and the contact threshold (MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015). In order for intergroup contact to have the most positive intergroup outcomes (i.e., attitudes, behavior, policy support, and collective action) for both disadvantaged and advantaged group members, reaching the contact threshold (whereby intergroup interactions are positive and outgroup members are considered as potential friends) AND focusing on group differences and recognizing group inequalities within intergroup relationships is necessary. That is, reaching the contact threshold is a necessary—but not sufficient—prerequisite to intergroup contact resulting in the most positive intergroup outcomes (i.e., positive attitudes, positive behavior, policy support, and collective action support/participation) for all. In intergroup interactions disadvantaged group members report desire for focus on group differences and group inequality and a chance to offer their perspective (Bruneau & Saxe, 2012), whereas advantaged group members prefer to focus on group commonalities (Saguy & Kteily, 2014). This is not surprising, given that intergroup interactions involving these conditions is difficult and anxiety provoking, especially for advantaged group members who regularly benefit from the status quo (Saguy & Kteily, 2014). However, we contend that when contact involves recognition of group differences and group inequality after reaching of the contact threshold, there is potential for positive outcomes overall. Consistent with MacInnis and Page-Gould, we propose that outcomes will be most ideal when these conditions are present in close, lasting cross-group friendships. That is, rather than simply having a cross-group friend, being (for advantaged group members) or having (for disadvantaged group members) a cross-group friend that is an ally to the disadvantaged group is likely to be most beneficial.

This may seem counterintuitive, however, given that the well-established finding that cross-group friendships predict positive intergroup attitudes (Davies et al., 2011) and negative attitudes or emotions toward the advantaged group have been identified as precursors to collective action for disadvantaged group members (Becker & Tauch, 2015; Dixon, Tropp et al., 2010; van Zomeren, Spears, Fischer, & Leach, 2004). We propose, however, that in cross-group friendships where group inequality is recognized and disavowed, positive and negative group attitudes are not mutually exclusive. For the disadvantaged group member, a cross-group friendship involving regular discussion of group differences, recognition of group inequality, and explicit condemnation of group inequality by the advantaged group friend may promote more positive attitudes toward the advantaged group friend which generalize to his or her group as a whole, but at the same time encourage more negative attitudes toward the advantaged group and that promote or maintain commitment to policy support and collective action. It is suspected that such ambivalent attitudes toward one's own ingroup would also be held by advantaged group members in this type of friendship. For advantaged group members, this type of friendship may promote deprovincialization—that is, broadening one's perspective beyond the advantaged group (Pettigrew, 2011)—a mindset that may be more accepting of this ambivalence. Both positivity toward the outgroup and negativity toward the ingroup may predict policy support and collective action participation for advantaged group members. Although ambivalence is typically characterized as “bad” for intergroup relations (e.g., Glick & Fiske, 1996; Hoffarth & Hodson, 2014), we identify a situation where it may actually be a force for good. That is, for advantaged group members, positive attitudes toward one's ingroup (consistent with basic social identity processes, Tajfel & Turner, 1979) coexist with negative attitudes toward one's ingroup generated by having a close friendship with a disadvantaged group member where group inequality is recognized, discussed, and disavowed. These negative attitudes toward the ingroup then predict the support of policies and collective action aimed at reducing inequality. Indeed, negativity toward the advantaged ingroup in the form of collective guilt can promote reduced prejudice and increased social change motivation (Wohl, Branscombe, & Klar, 2006). Positive intergroup motivations resulting from collective guilt may be largely symbolic, however, and not beneficial for intergroup relations but rather for assuaging guilt (Thomas, McGarty, & Mavor, 2009). We refer to negative attitudes toward the ingroup more generally (of which collective guilt may be a component), suggesting that these negative attitudes developed through a cross-group friendship involving recognition of group inequality will have more reliably positive intergroup outcomes. For disadvantaged group members, positive attitudes toward one's outgroup generated by having a close friendship with an advantaged group coexist with negative attitudes toward the advantaged group generated by recognition, discussion and condemnation of group inequality within this friendship. These negative attitudes toward the outgroup go on to predict the support of policies and collective action aimed at reducing inequality. Thus, in this particular situation, ambivalent attitudes may be beneficial and motivate positive social change.

For a visual depiction of our proposed pattern, see Figure 1. We propose that after engaging in a number of intergroup interactions (this number will vary based on several factors, MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015), a threshold will be reaching whereby intergroup contact produces positive outcomes such as less prejudice. Upon reaching the contact threshold outgroup members may be viewed as potential friends (MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015), and one may form a cross-group friendship. Consistent with previous work, this will promote more positive attitudes toward the friend, which will generalize to the group as a whole (e.g., Davies et al., 2011). This will also be associated with positive behavior toward the group and sustained openness to cross-group friendships. We propose that when the friendship involves recognition of group differences/group inequality and condemnation of group inequality, that this will not only strengthen the relationship between the friendship and positive attitudes toward one's outgroup friend, but also promote heightened negative attitudes toward the advantaged group and its position. When the friendship involves these qualities, this will predict negative attitudes toward the advantaged group among both disadvantaged and advantaged group members. This negativity toward the advantaged group will then promote the support of policies and collective action aimed at reducing inequality (see Figure 1).

We also recognize the possibility that this type of cross-group friendship may stimulate more positive attitudes toward the friend, but that these more positive attitudes would only generalize to the friend's group for advantaged group members and not for disadvantaged group members. The friend may be viewed as an “exception” for disadvantaged group members, especially those with a strong history of negative intergroup contact, and therefore attitudes toward one advantaged group member may not generalize to the group as a whole. Or, it may take more time or more of these cross-group friendships in order for generalization to occur. Generalization may occur more readily for advantaged group members who have less experience with intergroup contact and hence less personal experience with the disadvantaged group to draw on.

8.1 Future research directions

The kind of cross-group friendships we describe above—and, cross-group friendships generally—are not particularly common in real life (Dixon et al., 2005; Jackman & Crane, 1986). This is not surprising, given that advantaged group members avoid interactions involving recognition of group inequality (Saguy & Kteily, 2014). A challenge for future researchers is to identify the conditions under which these rare relationships do occur naturally, and examine means by which to induce them in both the lab and—most critically—real life. What might an intervention look like to promote these relationships and associated outcomes? A starting point may be for diverse environments to promote recognition of group memberships and group inequality. Ideally, this would promote rejection of group inequality and cross-group friendships formed in this environment would involve recognition of group memberships and condemnation of group inequality. Even better would be interventions involving these components coupled with conditions aimed at supporting cross-group friendship formation. One potentially promising intervention among school children involves the former. In Fieldston Lower School in New York City, a program aimed at promoting racial equity involves students—starting in the third grade (i.e., 8 years old)—meeting regularly with racial ingroup members to discuss their racial group membership and the challenges associated with it (e.g., how they were perceived by others based on group membership). Then, children gather in a mixed-race setting to share and discuss what they learned in ingroup groups (L. Miller, 2015). Certainly, this involves explicit recognition of group membership and likely highlights racial inequality and its negative consequences for both disadvantaged and advantaged group members. Thus, the cross-race friendships of children participating in this program may be likely to promote not only more positive intergroup attitudes but also more positive intergroup behavior, collective action, and supporting of policies aimed at reducing inequality. This potential remains unknown empirically, however, and the evaluation of interventions represent an important avenue for future research.

A potential avenue for identifying conditions under which these rare friendships occur naturally is to explore cross-group friendships where both the disadvantaged and advantaged group member are relatively low in social dominance orientation. Social dominance orientation (SDO) is an individual difference characterized by preference for hierarchical intergroup relations and support of inequality (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Whereas those relatively higher in SDO can benefit from intergroup contact in terms of more positive attitudes (e.g., Hodson, 2011; Hodson, Costello, & MacInnis, 2013), those relatively lower in SDO may benefit from intergroup contact in terms of collective action and policy support. Recognition of group memberships and condemnation of group inequality may occur naturally in cross-group friendships where both friends are lower in SDO. Indeed, recent evidence supports the notion that those lower (vs. higher) in social dominance orientation, when in contact with the outgroup, show greater support for policy support to redistribute outcomes (Tausch et al., 2017). It is especially likely that disadvantaged group members lower in SDO would be interested in recognizing and challenging group hierarchies in their relationships (Henry, Sidanius, Levin, & Pratto, 2005), but advantaged group members lower in SDO may do as well as a means to demonstrate commitment to undermining group inequality (Saguy & Kteily, 2014). Additionally, being relatively higher in SDO or right-wing authoritarianism (RWA, i.e., submission to authority, conventionalism, and aggression toward norm violators, Altemeyer, 1996) may influence the speed with which a contact threshold can be reached or whether a contact threshold can be reached at all (MacInnis & Page-Gould, 2015). These individual differences are important factors to consider in future research, as they can help to illuminate boundary conditions and inform interventions.

It is also important to test our proposed pattern in a variety of cultures and geographic areas. The majority of intergroup contact research employs “WEIRD” (i.e., Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic; Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010) samples (see Bilewicz, 2012). The results of these studies and the theoretical model we have introduced based upon these results may not generalize to all geographic areas. Finally, the field would benefit from a clearer operationalization of collective action and the goals of collective action. Does collective action mean action by both disadvantaged and advantaged group members, as we have considered it here, or does action by advantaged group members represent something distinct? Action by advantaged group members can take a number of forms including (a) participating together with the disadvantaged group (e.g., men marching at an anti-sexism demonstration), and (b) participating in advocacy on the behalf of the group (e.g., men accepting a pay reduction to equalize pay for female coworkers). There may be differences in the relationship between intergroup contact and these different forms of advantaged group collective action. Furthermore, the operationalization of collective action may vary based on the perceived goal of the collective action. Goals of collective action could include redistribution of resources or power, obtaining a sense of justice, or simply broad scale recognition of challenges faced by the disadvantaged group. Future research can examine whether the relationship between intergroup contact and collective action varies as a function of these nuances.

9 CONCLUSION

Interest in the contact hypothesis has shown a marked spike over the past two decades (see Hodson & Hewstone, 2013b, Fig. 1.1). This is of little wonder, given the general effectiveness of contact (relative to other interventions) in reducing prejudicial attitudes. In addressing why contact might appear less effective in building support for collective action, we propose that intergroup contact can promote active intergroup outcomes under certain conditions. After reaching a contact threshold, intergroup contact in the form of close bonds (i.e., friendship) involving recognition of group differences and condemnation of group inequality may promote ambivalent attitudes toward the advantaged group. For advantaged group members, such a friendship would promote positive attitudes toward the disadvantaged group (through the generalization of attitudes from friend to outgroup) but also negative attitudes toward the ingroup and its advantaged position the given explicit recognition and discussion of unfair group inequality in the relationship. For disadvantaged group members, such a friendship would promote positive attitudes toward the advantaged group (through the generalization of attitudes from friend to outgroup) but also negative attitudes toward the advantaged group given explicit recognition and discussion of unfair group inequality in the relationship. That is, in a cross-group friendship involving these qualities, a disadvantaged group member could feel justified holding negative attitudes toward the advantaged group because the advantaged group friend also holds these attitudes. This negativity toward the advantaged group may promote collective action aimed at reducing inequalities for both advantaged and disadvantaged group members. The question, therefore, is not whether contact and friendship promote collective action, but when. Cross-group relations that recognize the inequalities presumably play a key role in shaping the factors that determine whether intergroup relations improve or sour.