Low Rates of Digital Rectal Exam in an Academic Health System Represent a Missed Opportunity

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives

Digital rectal exam (DRE) is an important screening tool for early cancer identification. DRE has become less routinely performed following removal from cancer screening guidelines. The effect of this decreased utilization has not been studied; this study sought to evaluate current DRE utilization and changes over time.

Methods

The electronic medical record database of a regional academic health system was assessed between 2015 and 2020 for encounters with patients aged 45–75. DRE rates and yearly trends were assessed using chi-squared and Cochran–Armitage tests, respectively.

Results

Of 191 329 outpatient encounters, DRE was documented on 8.5% of visits. DRE utilization declined from 2015 to 2020 (9.6% vs. 8.9%). DRE was more often identified as a procedure in surgical specialties, including surgical oncology (55.6%) and general surgery (2.8%), compared to primary care specialties, including family medicine (1.7%) and internal medicine (1.6%). DREs were less frequently documented for non-Hispanic Black patients versus non-Black patients (7.2% vs. 8.4%) and for Hispanic patients versus Non-Hispanic White patients (7.6% vs. 8.5%). Men had a documented DRE procedure more frequently than women overall (10.4% vs. 4.6%) and in encounters with primary care specialties (2.3% vs. 0.5%) and surgical specialties (20.4% vs. 13.5%) (all p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In this contemporary evaluation, DRE was less frequently coded during outpatient clinic visits overall and specifically in primary care compared with surgical specialties. Differences in DRE utilization across sociodemographic factors highlight disparities in cancer screening. Low DRE rates represent a missed opportunity for early identification of high prevalence cancers.

Abbreviations

-

- AAFP

-

- American Academy of Family Physicians

-

- AAPI

-

- American and Pacific Islander

-

- AUA

-

- American Urological Association

-

- DRE

-

- digital rectal exam

-

- FOBT

-

- fecal occult blood test

-

- FIT

-

- fecal immunochemical test

-

- ICD

-

- International Classification of Diseases

-

- mpMRI

-

- multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging

-

- NCCN

-

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

-

- NMEDW

-

- Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse

-

- PSA

-

- prostate-specific antigen

1 Introduction

Prostate and colorectal cancer are amongst the most frequently diagnosed malignancies worldwide [1]. Colorectal cancer is the third most prevalent cancer in both men and women in the United States, with prostate cancer being the most prevalent for men [2]. Given this high national and global prevalence, there is a need for early identification of these neoplasms [3, 4]. Historically, the screening processes for these lesions included the digital rectal exam (DRE), which had long been part of the standard physical exam [5-7]. For prostate cancer screening, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) previously recommended the administration of both the DRE and the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test annually for men aged 40 and older [8]. For colorectal cancer screening, patients have undergone various combinations of DRE, fecal occult blood test (FOBT), barium enema, sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy [9, 10].

As these high prevalence cancers continue to impact patients, new technologies aim to enhance and facilitate screening processes. For instance, options for prostate cancer screening have expanded with the introduction of the multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) and RNA-based biomarkers [11-13]. Likewise, the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) and serum testing have provided patients with colorectal cancer screening alternatives, which have gained popularity in individuals who prefer a noninvasive approach [14, 15]. As these novel techniques are applied in clinical practice, historically used screening techniques, such as the DRE, have become less utilized by physicians. For example, research has shown that there have been low rates of adherence to the American Urological Association's (AUA) guidelines for men presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms, with primary care physicians and urologists performing DREs less often than recommended [16]. Additionally, with the efficacy of the DRE being called into question by the current literature, cancer screening guidelines have shifted [17, 18]. Most notably, in recent years, the NCCN has omitted the DRE from their guidelines for cancer screening. However, in contrast to other testing, DRE can be performed in the office during a physical exam, reducing issues of non-adherence.

Following the alterations to these guidelines, it is unclear how the utilization of the DRE in clinical practice has changed. The objectives of this study are to (1) evaluate the utilization of the DRE across various specialty types, (2) assess differences in the rates of DRE across sociodemographic factors, and (3) analyze how rates of DRE utilization have changed over time.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design, Source, and Participants

This study is a retrospective observational cohort analysis of patients between the ages of 45 and 75 who were seen in Northwestern Medicine clinics for annual physical or nonemergency evaluation. The Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse (NMEDW), which integrates all electronic health records, was used to identify in-person patient encounters between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2020.

2.2 Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristic Variables

Demographic variables, including race, ethnicity, and gender, were collected. Race and ethnicity were categorized as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI), Native American and Alaska Native, or unknown. Clinical encounter characteristics, including department specialty, visit type, encounter diagnosis, receipt of DRE, and cancer diagnosis (i.e. prostate, anal, rectal, or colon), were also extracted. Receipt of DRE was determined based on plain text documentation in patients' charts, and cancer diagnoses were identified based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) or 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes. Specialties were classified as either being primary care (i.e. internal medicine, family medicine, and other primary care) or surgical (i.e. general surgery, surgical oncology, and urology). Visit type was categorized as new patient, return or follow-up, procedure, or annual exam. Encounter diagnoses were extracted from plain text in patient charts. Diagnoses of interest included, but were not limited to, abnormal prostate findings, abnormal/elevated PSA tests, malignant neoplasms of the prostate or colon, rectal adenocarcinoma, rectal bleeding, rectal prolapse, and hemorrhoids. Given that one patient may have returned for numerous nonemergency evaluations during the studied time frame, demographic counts were reported both by encounter and by unique patient.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Rates of DRE utilization were derived by calculating the percentage of encounters with DRE receipts for each variable of interest (i.e. gender, race and ethnicity, specialty, year, encounter diagnosis, and cancer type). Primary care DRE rates and surgical specialty DRE rates were also determined per variable of interest based on the department specialty associated with each encounter. Differences in DRE rates between specialty types, racial and ethnic groups, and genders were assessed using two-sided chi-squared tests. Changes in DRE rates over time were assessed with the Cochran–Armitage test for trend. P-values were derived using two-tailed tests, and a value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel version 16.82, GraphPad, and MedCalc software.

3 Results

3.1 Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The final cohort for analysis included 191 329 outpatient encounters with a total of 29 782 unique patients over a 6-year period. Out of the unique patients included in the analysis, the majority were male (69.3%) or non-Hispanic White (64.1%) (Table 1). Out of all encounters, most encounters were return or follow-up appointments (64.0%), and most patients were seen by the department of internal medicine (51.1%), with the department of urology seeing the second-most patients (34.7%) (Table 2).

| Demographics | Number of encounters | % of Column | Number of unique patients | % of Column |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 203 048 | 100.00 | 30 259 | 100.00 |

| Encounter type | ||||

| Telehealth | 11 719 | 5.77 | 477 | 1.58 |

| Non-telehealth | 191 329 | 94.23 | 29 782 | 98.42 |

| Non-telehealth characteristics | 191 329 | 100.00 | 29 782 | 100.00 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 127 832 | 66.81 | 20 634 | 69.28 |

| Women | 63 497 | 33.19 | 9148 | 30.72 |

| Racial/ethnic identity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 128 058 | 66.93 | 19 075 | 64.05 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 28 036 | 14.65 | 3486 | 11.71 |

| Hispanic | 14 715 | 7.69 | 2274 | 7.64 |

| AAPI | 5470 | 2.86 | 885 | 2.97 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 603 | 0.32 | 61 | 0.20 |

| Unknown | 14 447 | 7.55 | 4002 | 13.44 |

- Note: Bold values are used to delineate the demographics in Table 1. The bolded “Total” values consist of both telehealth and non-teleheath encounters, whereas the rest of the demographics pertain only to “Non-telehealth characteristics.”

- Abbreviation: AAPI, Asian American and Pacific Islander.

| Encounter characteristics | Number of encounters | % of Column |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 203 048 | 100.00 |

| Encounter type | ||

| Telehealth | 11 719 | 5.77 |

| Non-telehealth | 191 329 | 94.23 |

| Non-telehealth characteristics | 191 329 | 100.00 |

| Visit type | ||

| New | 32 215 | 16.84 |

| Return/follow-up | 122 508 | 64.03 |

| Procedure | 12 903 | 6.74 |

| Annual exam | 23 703 | 12.39 |

| Department Specialty | ||

| Internal medicine | 97 693 | 51.06 |

| Family medicine | 3974 | 2.08 |

| Primary care | 12 025 | 6.28 |

| General surgery | 1205 | 0.63 |

| Surgical oncology | 9983 | 5.22 |

| Urology | 66 449 | 34.73 |

| Year | ||

| 2015 | 21 822 | 11.41 |

| 2016 | 18 484 | 9.66 |

| 2017 | 21 526 | 11.25 |

| 2018 | 39 273 | 20.53 |

| 2019 | 51 170 | 26.74 |

| 2020 | 39 054 | 20.41 |

3.2 Rates of DRE Utilization

Overall, DRE was documented on 8.5% of clinic visits. Out of all specialties included in the analysis, DRE was most frequently coded during encounters with surgical oncology (55.6%) and least frequently coded during encounters with internal medicine (1.6%). When comparing the surgical specialties, including general surgery, surgical oncology, and urology, to the primary care specialties, including internal medicine, family medicine, and other primary care specialties, DRE was more frequently documented amongst the surgical specialties (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Specialty name | Specialty type | DRE rate (%) | p-value (surgical vs primary care) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General surgery | Surgical | 2.82 | < 0.001 |

| Surgical oncology | Surgical | 55.63 | |

| Urology | Surgical | 13.36 | |

| Internal medicine | Primary care | 1.57 | |

| Primary care | Primary care | 1.60 | |

| Family medicine | Primary care | 1.74 |

- Abbreviation: DRE, Digital rectal exam.

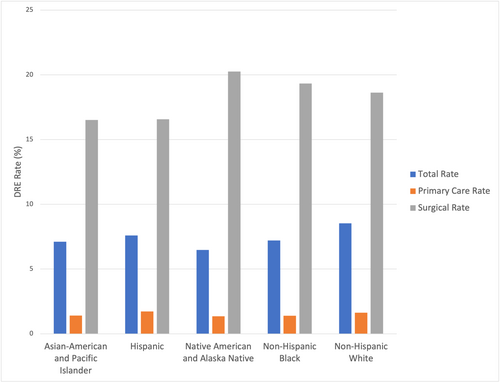

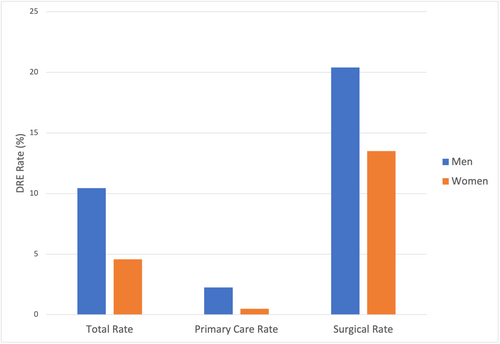

When comparing DRE rates by race and ethnicity, DRE was less frequently coded overall for Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients (7.6% vs. 8.5%, p < 0.001), and for non-Hispanic Black patients compared to non-black patients (7.2% vs. 8.4%, p < 0.001). Out of the primary care encounters, DRE was less frequently documented amongst non-Hispanic Black patients compared to non-Black patients (1.4% vs. 1.6%, p = 0.02). Out of the encounters with surgical specialties, Hispanic patients had less frequently documented DREs compared to non-Hispanic White patients (16.6% vs. 18.6%, p < 0.001), whereas non-Hispanic Black patients had more frequently documented DREs compared to non-Black patients (19.3% vs. 18.4%, p = 0.03) (Table 4) (Figure 1). When comparing DRE rates by gender, men overall had more frequently coded DREs than women (10.4% vs. 4.6%, p < 0.001), including out of all encounters with primary care specialties (2.3% vs. 0.5%, p < 0.001) and surgical specialties (20.4% vs. 13.5%, p < 0.001) (Table 5) (Figure 2).

| DRE rate (%) | Ethnic/racial identity | p-value (non-Hispanic White vs Hispanic) | Ethnic/racial identity | p-value (non-Hispanic Black vs non-Black) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Black | |||

| Total rate | 8.53 | 7.60 | < 0.001 | 7.21 | 8.38 | < 0.001 |

| Primary care rate | 1.63 | 1.73 | 0.48 | 1.39 | 1.63 | 0.02 |

| Surgical rate | 18.63 | 16.56 | < 0.001 | 19.33 | 18.36 | 0.03 |

- Abbreviation: DRE, Digital rectal exam.

| DRE rate (%) | Gender | p-value (men vs women) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||

| Total rate | 10.44 | 4.58 | < 0.001 |

| Primary care rate | 2.25 | 0.49 | < 0.001 |

| Surgical rate | 20.41 | 13.50 | < 0.001 |

- Abbreviation: DRE, Digital rectal exam.

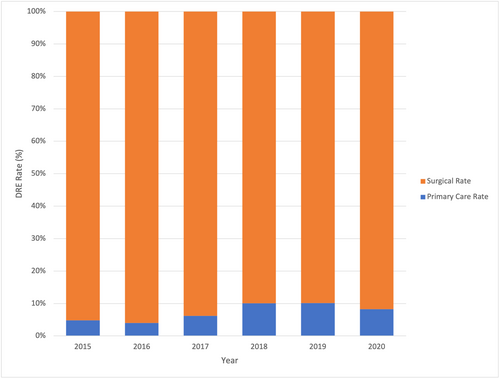

DRE rates significantly differed over time from 2015 to 2020. Notably, there was an overall decrease in DRE rates from 2015 to 2020 (9.6% vs. 8.9%, p < 0.001), especially across surgical specialties (26.0% vs. 18.3%, p < 0.001). On the other hand, there was a slight increase in DRE rates for primary care specialties from 2015 to 2020 (1.3% vs. 1.5%, p < 0.001) (Table 6) (Figure 3).

| DRE rate (%) | Year | p-value (over time) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ||

| Total rate | 9.57 | 11.00 | 7.03 | 7.73 | 8.02 | 8.91 | < 0.001 |

| Primary care rate | 1.31 | 1.31 | 1.26 | 1.91 | 1.78 | 1.47 | < 0.001 |

| Surgical rate | 26.04 | 31.58 | 19.1 | 17.1 | 15.79 | 16.28 | < 0.001 |

- Abbreviation: DRE, Digital rectal exam.

When categorizing patients based on cancer diagnoses, DREs were most frequently coded for patients with anal cancer (41.4%), followed by patients with rectal cancer (37.5%), prostate cancer (17.5%), or colon cancer (13.2%). Similar results were observed for encounters with surgical specialties; DREs were most frequently documented for patients with anal cancer (62.2%), followed by patients with rectal cancer (45.1%), prostate cancer (25.1%), or colon cancer (24.2%). Trends in DRE rates were slightly different for primary care encounters, with the most DREs being documented for patients with rectal cancer (7.7%), followed by patients with prostate cancer (1.3%), colon cancer (0.7%), or anal cancer (0.4%) (Table 7). Notably, non-Hispanic White patients and non-Hispanic Black patients had the highest rates of prostate cancer (9.6% and 9.1%, respectively). Furthermore, colon cancer was diagnosed most frequently amongst non-Hispanic White patients (1.1%), non-Hispanic Black patients (1.3%), and AAPI patients (1.1%).

| DRE Rate (%) | Cancer type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate | Rectal | Anal | Colon | |

| Total rate | 17.47 | 37.50 | 41.43 | 13.22 |

| Primary care rate | 1.33 | 7.69 | 0.35 | 0.67 |

| Surgical rate | 25.12 | 45.10 | 62.19 | 24.16 |

- Abbreviation: DRE, Digital rectal exam.

When assessing the DRE rates for patients who presented with anorectal complaints, DREs were overall more frequently coded for patients who were diagnosed with a rectal nodule (58.3%), rectal mass (52.0%), or abnormal prostate (51.6%). By comparison, DREs were less frequently coded for patients diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm of the colon (9.2%), rectal lesion (17.7%) or prostate cancer screening (18.4%). Out of the primary care encounters, DREs were more frequently documented for patients with abnormal prostate (30.4%), rectal mass (30.0%), or rectal pain (25.3%), and DREs were less frequently documented for patients with rectal adenocarcinoma (0.0%), rectal lesion (0.0%), or rectal tumor (0.0%). Out of the encounters with surgical specialties, DREs were more frequently coded for patients with a rectal nodule (85.7%), hemorrhoids (77.6%), or rectal pain (75.4%), and DREs were less frequently coded for patients with elevated PSA (25.3%), malignant neoplasm of the colon (26.3%), or abnormal PSA (27.1%) (Table 8).

| Encounter diagnosis | DRE rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total rate | Primary care rate | Surgical rate | |

| Abnormal prostate | 51.55 | 30.43 | 58.11 |

| Abnormal PSA | 22.52 | 1.53 | 27.07 |

| Elevated PSA | 20.55 | 4.24 | 25.34 |

| Malignant neoplasm of prostate | 23.80 | 1.95 | 28.26 |

| Prostate cancer screening | 18.38 | 4.01 | 32.41 |

| Prostate nodule | 33.69 | 11.76 | 41.82 |

| Malignant neoplasm of colon | 9.21 | 2.12 | 26.27 |

| Rectal adenocarcinoma | 35.79 | 0.00 | 50.00 |

| Rectal abscess | 25.89 | 3.13 | 56.25 |

| Rectal bleeding | 29.48 | 13.43 | 52.23 |

| Rectal lesion | 17.65 | 0.00 | 60.00 |

| Rectal mass | 52.00 | 30.00 | 66.67 |

| Rectal nodule | 58.33 | 20.00 | 85.71 |

| Rectal pain | 44.87 | 25.26 | 75.41 |

| Rectal prolapse | 47.95 | 3.45 | 58.97 |

| Rectal tumor | 33.33 | 0.00 | 33.33 |

| Hemorrhoids | 51.30 | 10.16 | 77.61 |

- Abbreviations: DRE, Digital rectal exam; PSA, Prostate-specific antigen.

4 Discussion

The results of this study show that the DRE is infrequently utilized in clinical practice, particularly in primary care settings. Patients from marginalized sociodemographic backgrounds received significantly fewer DREs compared to patients from majority racial, ethnic, and gender groups, highlighting a potential disparity in access to comprehensive physical evaluations. Especially considering how there were low rates of DRE utilization for patients diagnosed with high prevalence cancers, such as prostate or colon cancer, this pattern of utilization represents a missed opportunity for early identification and follow-up of malignant neoplasms.

These infrequent rates of DRE utilization in clinical practice are consistent with trends in the literature, which indicate that the DRE has less efficacy when compared to alternative screening techniques [17, 18]. Especially as noninvasive screening tools have become increasingly validated by research, there appears to be an evident shift away from utilizing the DRE in primary care settings [17]. However, it is important to consider that even with these novel technologies and limited evidence regarding the efficacy of the DRE, research shows that the DRE can still provide a benefit in detecting and diagnosing high prevalence diseases, such as prostate cancer, especially when used in conjunction with other screening methods [18]. It is also important to consider that these studies do not take into consideration the benefit that the DRE may have for patients who are hesitant to receive cancer screening. For instance, there are patients who may not want to be screened for cancer but consent to a physical exam, including the DRE. If this exam is abnormal, these patients may be motivated to pursue more comprehensive screening, resulting in earlier intervention and improved outcomes. Furthermore, DRE was underutilized for other anorectal complaints, such as rectal pain or lesions. Since these complaints may not be effectively assessed using alterative screening tools, as with prostate and colorectal cancer, this decrease in DRE utilization could prevent patients with anorectal complaints from receiving comprehensive evaluation and care.

The decrease in rates of DRE for primary care specialties compared to surgical specialties indicates underlying differences in utilization across specialty types. It is important to note that the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) advises primary care physicians to not routinely screening for prostate cancer. Instead, family physicians are encouraged to utilize the DRE in a shared decision-making manner for men who are interested in pursuing screening [19]. Furthermore, it is understandable why rates of DRE utilization were consistently higher amongst surgical subspecialties. These patients were likely referred to surgical subspecialties to receive procedural intervention for anorectal complaints and therefore would have been more likely to receive a comprehensive physical exam, including a DRE.

The decreased rates of DRE utilization for patients of racial and ethnic minorities, including non-Hispanic Black patients and Hispanic patients, may be indicative of a disparity in access to cancer screening. This discrepancy in regard to DRE utilization may be due to a combination of physician bias and cultural beliefs that interfere with these patients seeking cancer screening [20-25]. Additional barriers for this patient population include the cost of screening, access to healthcare, and lack of knowledge [26, 27]. Even with informed decision-making interventions, research has shown that Black men still receive low rates of DRE utilization [28]. This disparity in cancer screening also extends to other non-White racial groups, including American Indian/Alaska Native men [29]. Additional sociodemographic factors, including age, education, and access to healthcare, also impact patients' ability to receive screening via DRE [30]. As a result, it is important for physicians to consider individualized barriers for their patients, including cultural, sociodemographic, and financial concerns, when discussing cancer screening to mitigate these disparities.

Notably, women underwent significantly less DREs compared to men, highlighting another potential disparity in provision of cancer screening and assessing anorectal complaints. Firstly, it is important to consider that a primary indication for receipt of DRE is prostate cancer screening, which does not apply to patients without a prostate. As a result, it would be expected for women to have lower rates of DRE in clinical practice. However, it is possible that other factors may also be contributing to this decrease in DRE utilization for female patients. For instance, there may be physician bias in regard to administering the DRE for female patients, perhaps due to a belief that women do not need to receive the DRE for other anorectal complaints as prostate cancer tends to be the primary indication for DRE, which does not apply to them. Likewise, physicians may assume or hope that women are undergoing DRE in their gynecologist's office, making them less likely to administer DREs during other healthcare visits.

Overall, fear of discomfort plays a considerable role in preventing patients from pursuing prostate and colorectal cancer screening, particularly when it comes to receiving a DRE [31]. Given that the DRE is a more vulnerable, uncomfortable exam compared to alternative screening techniques, it is understandable why both physicians and patients would be hesitant to utilize this screening practice. However, it is important to note that these negative beliefs regarding the DRE may change following informed decision-making and experiencing a DRE firsthand. For example, one study demonstrated that although many patients had prior negative beliefs and concerns about the DRE, these beliefs changed after the patients received a DRE for the first time [32]. Likewise, another study showed that for patients who had previously received a DRE, the discomfort that they experienced during the exam did not prevent them from receiving another DRE in the future [33]. Therefore, physicians should consider and discuss these concerns with patients to alleviate fears that may serve as a barrier to cancer screening.

There are several limitations associated with this study. For instance, it is possible that some of the physicians did not report that they performed DREs in their post-encounter notes. As a result, the true rates of DRE utilization may be underrepresented by this study. Likewise, some physicians reported encounter diagnoses under different terminology or codes, so it is possible that some of these diagnoses were unintentionally excluded during the analysis, which could have lowered the rates of DRE utilization. In addition, since data was collected from a single academic institution in an urban setting, there is sampling bias associated with the patient population that was included in the analysis. As a result, there are some populations that are underrepresented in this study, which could potentially underscore some of the disparities that were observed in the results.

5 Conclusions

The DRE is infrequently performed as a screening practice in outpatient clinics and specifically in primary care settings. Differences in the rates of DRE utilization across sociodemographic factors highlight potential disparities and cultural barriers to accessing cancer screening for minority populations. As the utilization of the DRE declines, there is a missed opportunity for the identification of prostate and colorectal cancer, which could delay early intervention of these high prevalence, high risk malignancies.

Acknowledgements

DJV was supported by NIH SMART R38 grant number 5R38CA245095 and the Steven J. Stryker, MD, Gastrointestinal Surgery Research and Education Endowment. CDL was supported by the Health Services Research and Development Service of the Veterans Affairs grant number IIR 16-232 and by NIH grant number T37MD014248.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Synopsis for Tables of Contents

Digital rectal exam (DRE) has become less routinely utilized following removal from cancer screening guidelines, yet the effect of this has not been studied. This analysis of the electronic medical record database of a regional academic health system assessed the current utilization of DRE and changes over time. Low DRE rates, particularly in primary care settings, represent a missed opportunity for early identification of high prevalence cancers.