Survival benefit associated with screening of patients at elevated risk for pancreatic cancer

Abstract

Background & Objectives

Screening for pancreatic cancer is recommended for individuals with a strong family history, certain genetic syndromes, or a neoplastic cyst of the pancreas. However, limited data supports a survival benefit attributable to screening these higher-risk individuals.

Methods

All patients enrolled in screening at a High-Risk Pancreatic Cancer Clinic (HRC) from July 2013 to June 2020 were identified from a prospectively maintained institutional database and compared to patients evaluated at a Surgical Oncology Clinic (SOC) at the same institution during the same period. Clinical outcomes of patients selected for surgical resection, particularly clinicopathologic stage and overall survival, were compared.

Results

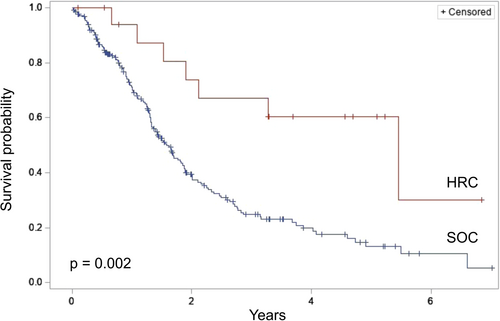

Among 826 HRC patients followed for a median (IQR) of 2.3 (0.8–4.2) years, 128 were selected for surgical resection and compared to 402 SOC patients selected for resection. Overall survival was significantly longer among HRC patients (median survival: not reached vs. 2.6 years, p < 0.001). Among 31 HRC and 217 SOC patients with a diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the majority of HRC patients were diagnosed with stage 0 disease (carcinoma in situ), while the majority of SOC patients were diagnosed with stage II disease (p < 0.001). Overall survival after resection of invasive PDAC was also significantly longer among HRC patients compared to SOC patients (median survival 5.5 vs. 1.6 years, p = 0.002).

Conclusion

Patients at increased risk for PDAC and followed with guideline-based screening exhibited downstaging of disease and improved survival from PDAC in comparison to patients who were not screened.

ACRONYMS

-

- EUS

-

- endoscopic ultrasound

-

- HRC

-

- high risk clinic

-

- IPMN

-

- intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

-

- MCN

-

- mucinous cystic neoplasm

-

- MRI

-

- magnetic resonance imaging

-

- PDAC

-

- pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

-

- SOC

-

- surgical oncology clinic

1 INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States and is expected to become the second leading cause by 2030.1, 2 A primary challenge in treating pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is that the majority of patients present with locally-advanced or metastatic disease, rendering them ineligible for potentially curative resection.3 Earlier detection of PDAC has long been considered essential to improving survival from the disease; however, there has been insufficient evidence to justify screening of asymptomatic average-risk individuals.4

Nonetheless, surveillance of certain patients who are at higher risk for PDAC has been recommended and is increasingly utilized. Patients at elevated risk for PDAC largely fall into two groups: individuals with a familial or genetic predisposition to developing PDAC and those with a cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Evidence-based screening guidelines for both groups have been proposed based on the recognition that earlier detection of premalignant and malignant lesions of the pancreas can lead to downstaging of the disease.5-11 Despite these recommendations, an improvement in long-term survival associated with screening has mostly been conducted in comparison to historical controls.12, 13 Accordingly, the 2020 International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium advised that further evidence was needed to demonstrate that surveillance improves survival from PDAC.6 Subsequently, the multicenter CAPS-5 results and updated CAPS1-5 results demonstrated a significant survival benefit for the screening cohort.14 Importantly, the CAPS studies enrolled patients with hereditary syndromes, germline variant carriers, and those with strong family history but did not include patients at risk for PDAC due to the presence of a neoplastic pancreatic cyst.

As such, the objective of this study was to assess the survival of patients enrolled in a pancreatic cancer surveillance clinic, including those with neoplastic cysts or those with CAPS criteria who underwent surgical resection. We aimed to compare these high-risk patients to patients who did not undergo surveillance but were also selected for surgical resection. We hypothesized that guideline-based screening of individuals at elevated risk for PDAC would be associated with downstaging of disease and improved overall survival.

2 MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1 Patient population

All patients enrolled at a High-Risk Pancreatic Cancer Clinic (HRC) within a single tertiary-referral academic medical center from July 2013 to June 2020 and selected for pancreatic resection were identified from a prospectively maintained institutional database and included in this observational cohort study. Similarly, patients who were not undergoing surveillance at the HRC but were evaluated at the Surgical Oncology Clinic (SOC) at the same academic medical center during the same time period who were selected for pancreatic resection were also identified for comparison. Patients with a history of a previous operation on the pancreas were excluded. Additionally, among the HRC and SOC patient cohorts, patients confirmed to have a pathologic diagnosis of PDAC (including patients with carcinoma in situ) were identified for subgroup analysis.

2.2 HRC patient enrollment and screening

HRC patients consisted of all patients referred for screening due to a familial or genetic predisposition to PDAC or due to a neoplastic cyst of the pancreas. Patients with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer (e.g., at least one first-degree relative and 1 s-degree relative with pancreatic cancer) or genetic germline mutation (e.g., patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; FAMMM syndrome [p16/CDKN2A mutation carriers]; ataxia-telangiectasia [ATM mutation carriers]; BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, TP53 or mismatch repair gene mutation carriers with 1 or more affected first or second-degree relatives) were screened in accordance with International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Consortium (CAPS) and/or National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.5, 15 Screening for these individuals was performed annually with either endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Patients were also selected for surgery as per CAPS and/or NCCN recommendations.

HRC patients with a neoplastic cystic lesion of the pancreas were managed according to the most recent Fukuoka Guidelines.7, 8 Briefly, patients with a cystic lesion (including intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms [IPMNs] and mucinous cystic neoplasms [MCNs]) that met criteria for surveillance (i.e., based on ductal location, size, and/or morphology) were followed with interval pancreatic protocol computed tomography (CT) or MRI/MRCP every 3–12 months, depending on the characteristics of the lesion. Additional workup with EUS and, ultimately, surgical resection was similarly performed in accordance with the latest Fukuoka Guidelines. All operations were performed by the same three surgeons (VMZ, RBA, TWB) for the HRC and SOC.

2.3 Variable definitions and outcome measures

All variables were captured within a prospectively maintained institutional database. Patient demographics included age at their initial clinic visit, sex, and self-reported race/ethnicity. Patient characteristics included risk factors for the development of PDAC, namely any history of obesity, diabetes, smoking, and alcohol use.16-20 Each patient's clinicopathologic diagnosis was grouped into one of the following categories: PDAC (including carcinoma in situ), cystic neoplasm (including IPMN, MCN, and serous cystadenoma), neuroendocrine tumor, pancreatitis, other malignant lesion (e.g., cholangiocarcinoma, duodenal adenocarcinoma, solid pseudopapillary tumor), or other benign lesion (e.g., adenoma, annular pancreas, pseudocyst). Among patients diagnosed with PDAC, additional variables included the patient's clinicopathologic stage at the time of surgery (per The American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] Cancer Staging Manual, 7th or 8th edition as appropriate21, 22), surgical procedure performed, and receipt of neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation.

The primary outcome of this study was overall survival from the time of surgery among HRC and SOC patients diagnosed with PDAC. Secondary outcomes of interest included the clinicopathologic stage of PDAC among HRC and SOC patients and overall survival among all HRC and SOC patients selected for surgical resection. Additionally, sensitivity analysis of overall survival among patients with invasive PDAC (i.e., not including carcinoma in situ) was performed to test the robustness of findings.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate for categorical variables. Overall survival was visualized with Kaplan-Meier curves and compared between groups using log-rank testing. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered significant, and all analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). The University of Virginia Institutional Review Board approved this study.

3 RESULTS

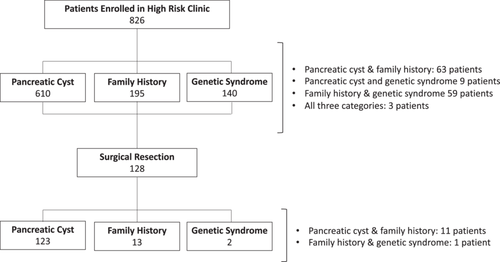

Among 826 eligible HRC patients followed for a median (IQR) of 2.3 (0.8–4.2) years, 128 were selected for surgical resection (Figure 1). During this same period, 402 patients evaluated at the SOC were similarly selected for surgery.

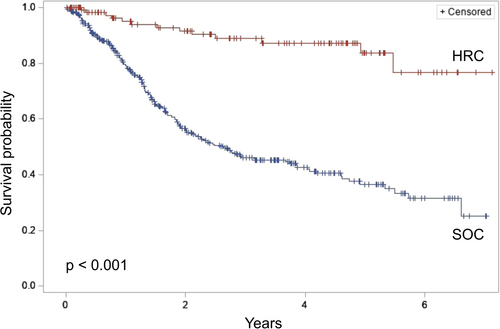

A comparison of HRC and SOC patients who underwent surgical resection is presented in Table 1. HRC and SOC patients were of similar age, though HRC patients were more likely to be female and of nonwhite race. HRC patients also demonstrated a greater prevalence of obesity and a history of alcohol use. Clinicopathologic diagnoses differed significantly between groups, with SOC patients more likely to be diagnosed with PDAC (54.0% vs. 24.2%) and neuroendocrine tumors (13.7% vs. 5.5%). In comparison, HRC patients were diagnosed more often with cystic neoplasms (59.4% vs. 1.2%, p < 0.001). Overall survival from the time of surgery was significantly longer among HRC patients (median survival: not reached vs. 2.6 years, p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

| SOC (N = 402) | HRC (N = 128) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 65.0 (56.4–72.3) | 65.8 (52.1–72.3) | 0.29 |

| Male sex | 223 (55.5%) | 52 (40.6%) | 0.003 |

| Race | 0.04 | ||

| White | 352 (87.6%) | 107 (83.6%) | |

| Black | 31 (7.7%) | 14 (10.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (0.8%) | 5 (4.0%) | |

| Asian | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Unknown | 14 (3.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Obesity | 105 (26.1%) | 45 (35.2%) | 0.048 |

| Diabetes | 121 (30.1%) | 41 (32.0%) | 0.68 |

| Smoking | 198 (49.3%) | 66 (51.6%) | 0.65 |

| Alcohol use | 164 (40.8%) | 66 (51.6%) | 0.03 |

| Diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| PDAC | 217 (54.0%) | 31 (24.2%) | |

| Invasive cancer | 217 (54.0%) | 18 (58.1%) | |

| Carcinoma in situ | 0 (0%) | 13 (41.9%) | |

| Cystic neoplasm | 5 (1.2%) | 76 (59.4%) | |

| Neuroendocrine | 55 (13.7%) | 7 (5.5%) | |

| Pancreatitis | 34 (8.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Other malignanta | 74 (18.4%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| Other benignb | 17 (4.2%) | 11 (8.6%) |

- Abbreviations: HRC, high risk clinic; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; SOC, surgical oncology clinic.

- a Includes: cholangiocarcinoma, duodenal adenocarcinoma, solid pseudopapillary tumor, metastatic carcinoma, and other diagnoses.

- b Includes: ampullary adenoma, pseudocyst, lipoma, lymphoma, and other diagnoses.

Among 31 HRC and 217 SOC patients with a pathologic diagnosis of PDAC, there were no differences in age, sex, or race, as presented in Table 2. However, HRC patients did demonstrate a greater prevalence of obesity and alcohol use than SOC patients. Importantly, HRC patients, compared to SOC patients, displayed a significantly lower clinicopathologic stage at the time of surgery, with most HRC patients demonstrating stage 0 disease (carcinoma in situ) compared to the majority of SOC patients exhibiting stage II disease (p < 0.001). Similarly, there were significant differences in the procedures performed between groups, with 15.2% of SOC patients undergoing an aborted or palliative procedure, while none of the HRC patient procedures were aborted or palliative (p = 0.04).

| SOC (N = 217) | HRC (N = 31) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 65.9 (57.9–73.4) | 66.5 (57.9–72.7) | 0.92 |

| Male sex | 117 (53.9%) | 16 (51.6%) | 0.81 |

| Race | 0.22 | ||

| White | 189 (87.1%) | 26 (83.9%) | |

| Black | 16 (7.4%) | 4 (12.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Asian | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (3.2%) | |

| Unknown | 10 (4.6%) | 0 (%) | |

| Obesity | 40 (18.4%) | 11 (35.5%) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 75 (34.6%) | 10 (32.3%) | 0.80 |

| Smoking | 105 (48.4%) | 19 (61.3%) | 0.18 |

| Alcohol use | 81 (37.3%) | 18 (58.1%) | 0.03 |

| Clinicopathologic stage | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 3 (1.4%) | 16 (51.6%) | |

| I | 41 (18.9%) | 6 (19.4%) | |

| II | 134 (61.8%) | 8 (25.8%) | |

| III | 26 (12.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| IV | 13 (6.0%) | 1 (3.2%) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 34 (15.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.01 |

| Neoadjuvant radiation | 16 (7.4%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.70 |

| Procedure | 0.04 | ||

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | 141 (65.0%) | 22 (71.0%) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 32 (14.8%) | 8 (25.8%) | |

| Total pancreatectomy | 11 (5.1%) | 1 (3.2%) | |

| Aborted/palliative procedure | 33 (15.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 74 (34.1%) | 8 (25.8%) | 0.36 |

| Adjuvant radiation | 17 (7.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.14 |

- Abbreviations: HRC, high risk clinic; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; SOC, surgical oncology clinic.

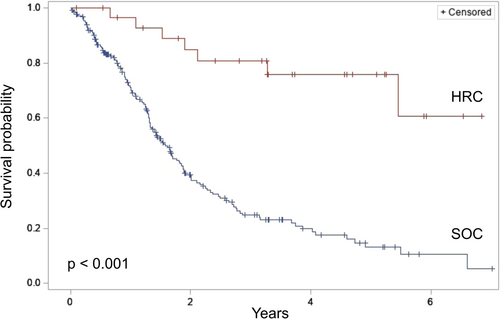

Comparison of overall survival from the time of surgery between HRC and SOC patients diagnosed with PDAC demonstrated a significantly improved survival among HRC patients (median survival: not reached vs. 1.6 years, p < 0.001) (Figure 3). Five-year survival was 75.7% among HRC patients versus 13.1% among SOC patients (p < 0.001). Sensitivity analysis of only patients with invasive PDAC revealed a persistent survival advantage among HRC patients (median survival: 5.5 vs. 1.6 years, p = 0.002) (Figure 4). Further sensitivity analysis of patients with invasive PDAC but excluding those who underwent an aborted or palliative procedure again demonstrated a survival advantage among HRC patients (median survival: 5.5 vs. 1.8 years, p = 0.005).

4 DISCUSSION

In this observational cohort study, over a 7-year period, elevated-risk patients who underwent resection for screening-detected PDAC demonstrated improved overall survival as compared to patients who were not screened and underwent resection for PDAC. This survival benefit associated with screening patients at higher risk for pancreatic cancer was likely attributable to early detection of PDAC, as evidenced by the significantly lower stage of disease among HRC patients. Additionally, the survival benefit of screening individuals at elevated risk was consistent upon comparison of individuals with any indication for surgery as well as individuals only diagnosed with invasive PDAC. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that screening patients at elevated risk for pancreatic cancer is associated with improved overall survival compared to individuals who are not screened. Just as screening individuals for breast and colon cancer has been demonstrated to improve survival,23, 24 the present study similarly supports screening of appropriately selected patients for pancreatic cancer.

The demonstration of a survival benefit through screening of higher-risk individuals for pancreatic cancer provides an important contribution to the current literature. Previous examinations of screening programs for individuals with a familial or hereditary risk of pancreatic cancer have largely focused on the incidence of PDAC and, in particular, the impact of surveillance on downstaging of PDAC.12, 13, 25-28 For example, the original Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) cohort study followed 216 asymptomatic high-risk individuals at 5 United States centers for a mean of 29 months, among whom 92 pancreatic lesions were identified—5 requiring pancreatectomy and 3 demonstrating high-grade dysplasia.26 Similarly, the subsequent CAPS cohort included 354 high-risk individuals with a median follow-up of 5.6 years, among whom 24 patients developed neoplastic progression to high-grade dysplasia or PDAC.12 Notably, 4 high-risk individuals within the CAPS cohort developed PDAC outside surveillance and subsequently demonstrated significantly worse long-term survival, providing one of the earliest hints of the impact of screening on survival. Accordingly, the 2020 update from the International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium specifically emphasized that pancreatic surveillance programs must demonstrate better evidence that survival from pancreatic cancer can be improved through screening.6 The CAPS-5 multicenter trial importantly demonstrated a survival benefit associated with screening among patients with hereditary syndromes, germline variant carriers, and those with strong family history; however did not include patients with cystic neoplasms of the pancreas.14 The present study fills this gap in the literature by providing a real-world experience outside of a clinical trial, demonstrating long-term survival among high-risk patients with screening-detected PDAC, including those who were followed for a cystic neoplasm.

This study also highlights the feasibility of including patients with neoplastic cysts as well as patients with a genetic or familial predisposition to pancreatic cancer in the same, multidisciplinary screening program. Though managed differently, these two patient populations both require frequent imaging of their pancreas and thus lend themselves well to being evaluated and counseled in the same clinic. Although the current study examined these populations as a single cohort, demonstrating a survival benefit associated with screening among those patients with a cystic neoplasm is noteworthy. To date, only a limited number of studies have evaluated the impact screening has on survival among patients with cystic neoplasms of the pancreas.29, 30 While the optimal strategies for screening and indications for surgical resection of cystic lesions of the pancreas continue to be updated,7, 8 the present study displays how survival can be improved through early detection of PDAC with careful consideration of screening guidelines and individualized patient management.

The prolonged survival among patients with screening-detected PDAC in this study is largely attributable to earlier detection and associated downstaging of disease. The majority of HRC patients selected for surgery were resected with stage 0 disease (carcinoma in situ), compared to SOC patients who were primarily diagnosed with stage II PDAC. Previous works corroborate this observation, with the downstaging of disease due to screening being one of the primary justifications for the surveillance of high-risk individuals and patients with cystic neoplasms.6-8, 30, 31 Notably, the present study only compared patients selected for surgical resection, meaning that many patients with locally-advanced or metastatic disease were excluded. A comparison of all patients evaluated at the HRC and SOC would likely include many more patients with stage III and IV PDAC at the SOC and highlight an even more pronounced downstaging of disease and survival associated with the screening of HRC patients. Despite this, one HRC patient was ultimately found to have stage IV PDAC during surgical resection, underscoring the need for earlier detection of premalignant disease and continued optimization of screening programs. Given the updated current NCCN guidelines for germline testing of all patients with PDAC,32 more patients and their families will continue to be identified that require pancreatic cancer screening. As such, these data are important and timely in supporting the screening of high-risk patients.

This study has several limitations. First, it is important to note that this study compares survival outcomes of higher-risk individuals who underwent pancreatic cancer screening to average-risk individuals who did not. A more rigorous assessment of a survival benefit associated with screening for pancreatic cancer would compare higher-risk individuals who were screened to other higher-risk individuals who were not screened. However, given that all individuals who met HRC inclusion criteria were referred for HRC enrollment at our institution, this comparison could not be performed. Additionally, it would be unethical to not offer screening to patients at high risk for pancreatic cancer, given current CAPS and Fukuoka guidelines. Second, database limitations only allowed for reliable comparison of patients undergoing surgical resection, and as such, a selection bias may exist. However, the inclusion of patients with unresectable and metastatic disease who were not selected for surgery—likely almost entirely SOC patients—would be expected to only further establish a relative survival benefit among HRC patients. Third, as with any observational evaluation of a screening intervention, this study is subject to lead time bias. Screened patients were detected to have PDAC at lower stages than non-screened patients, suggesting the survival benefit associated with screening may be an overestimate in part attributable to earlier detection. Despite this, demonstrating a long-term survival improvement among patients selected for surgery through early detection of PDAC is critically important, given that the vast majority of patients who undergo resection for PDAC develop disease recurrence and die within 5 years.33, 34 Fourth, the institutional database used in this study did not include detailed information on referral patterns, comorbid conditions, or cause of death, precluding more nuanced analyses such as disease-specific survival. Nevertheless, overall survival is generally a preferred outcome measure that, in the setting of an aggressive disease like PDAC, is less likely to be confounded by non-cancer causes of death. Finally, the results of this observational study should not be confused with causation. Future randomized studies are needed to confirm a causal link between screening and survival among patients at elevated risk for pancreatic cancer.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In sum, this study found that higher-risk patients—including those with neoplastic cysts and those with hereditary risk—who underwent screening for pancreatic cancer, had improved overall survival after surgical resection of PDAC as compared to patients who were not screened. Moreover, this long-term relative survival benefit was primarily attributable to downstaging of disease, with a majority of screening-detected patients resected with stage 0 PDAC (carcinoma in situ). These findings support screening for pancreatic cancer among patients with a strong family history of PDAC, genetic predisposition, or neoplastic cysts of the pancreas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant number: T32CA163177). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Wang discloses owning publicly traded stock in GE HealthCare Technologies and Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Owing to patient privacy restrictions, the research data used in this work are not shared.

REFERENCES

SYNOPSIS FOR TABLE OF CONTENTS

Guideline-based screening of patients at elevated risk for pancreatic cancer was associated with downstaging of disease and improved survival from pancreatic cancer in comparison to patients who were not screened