An organizational ethic of care and employee involvement in sustainability-related behaviors: A social identity perspective

Summary

We expand on the emergent research of an ethic of care (EoC) to theorize why and how an organizational EoC fosters employee involvement in sustainability-related behaviors at work. Across two studies, we explore the socio-psychological mechanisms that link an EoC and involvement in sustainability-related behaviors. The results of Study 1, in which we applied an experimental design, indicate that an EoC is significantly related, through employees' affective reaction towards organizational sustainability, to involvement in sustainability-related behaviors. In Study 2, in which we used time-lagged data, we further drew on social identity theory to suggest that an EoC is both directly and indirectly, through enhanced organizational identification, related to employees' satisfaction with organizational sustainability. Through these two mechanisms, we explain the process by which an EoC can drive employee involvement in sustainability-related behaviors. These theoretical developments and empirical findings help to better understand the micro-foundations of organizational sustainability by building upon the moral theorizing of care.

1 INTRODUCTION

The scale, scope, and complexity of environmental issues pose a major challenge for organizations and require them to mobilize substantial resources and capabilities to achieve a transition towards greater sustainability (Andersson, Jackson, & Russell, 2013; Zhu, Cordeiro & Sarkis, 2013). In attempts to understand how organizations respond to demands for sustainability, scholars tended to apply a macro-level approach and focus on the importance of formal management systems, processes, structures, and certifications (Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia, & Larraza-Kintana, 2010; Darnall, Henriques, & Sadorsky, 2010; Delmas & Toffel, 2008; Reid & Toffel, 2009; Walls, Berrone, & Phan, 2012).

However, a focus on formal structures and processes does not allow us to fully capture the micro-foundations of sustainability. An emergent stream of research in the fields of organization theory and strategy points to the importance of micro-foundations in explaining higher level phenomena (Barney & Felin, 2013; Felin & Foss, 2005; Foss, 2011; Foss & Linderberg, 2013; Powell, Lovallo, & Fox, 2011). Such a search for micro-foundations of significant organizational and strategic phenomena have begun to make significant contributions to research in entrepreneurship (Dai, Roundy, Chok, Ding, & Byun, 2016), human resource management (Raffiee & Coff, 2016), organization studies (Jones, 2016), and strategy (Aguinis & Molina-Azorín, 2015; Felin, Foss, Heimeriks, & Madsen, 2012; Greve, 2013). Despite the importance of a micro-level perspective, research on “micro-foundations of CSR (i.e., foundations of CSR that are based on individual actions and interactions)” has yet to be fully developed (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012, p. 956). Specifically, we need to direct attention to examine micro-level mechanisms that help translate “higher level variables” into behaviors and actions that may benefit the organization (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; see also Carmeli, Gilat, & Waldman, 2007; Graves, Sarkis, & Zhu, 2013; Ones & Dilchert, 2012; Ramus & Steger, 2000; Robertson & Barling, 2013).

Revealing what underpins one's involvement in sustainability initiatives can inform research and theory of organizational or corporate sustainability and social responsibility (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012) for at least two main reasons. First, we know that employees' involvement and engagement at work play a crucial role in driving important organizational-level outcomes (Macey, Schneider, Barbera, & Young, 2009). Second, driving and enhancing sustainability is a complex task, which requires the collective effort and collaborative involvement of all organizational actors (Daily, Bishop, & Govindarajulu, 2009; Norton, Parker, Zacher, & Ashkanasy, 2015; Ones & Dilchert, 2012). Oftentimes, however, driving sustainability depends on employees' discretionary efforts and behaviors (Lamm, Tosti-Kharas, & Williams, 2013; Ramus, 2001; Ramus & Killmer, 2007), but their underlining drivers remain relatively understudied (Tosti-Kharas, Lamm, & Thomas, 2016). This led scholars to call for adopting a behavioral perspective in examining how transitions to greater sustainability might be achieved (Andersson et al., 2013; Norton et al., 2015; Paillé & Raineri, 2016). For example, research examined both the antecedents of employee pro-environmental behavior (Whillans & Dunn, 2015; Wiernik, Dilchert, & Ones, 2016), as well as how attractive is organizational sustainability for newcomers (Jones, Willness, & Heller, 2016). This stream of research sheds light on the conditions in which employees are more likely to engage in discretionary pro-sustainability behaviors at work (Boiral, Talbot, & Paillé, 2013; Lamm et al., 2013). At the same time, relatively little attention has been paid to the need to more directly and explicitly examine the relationships and the ways organizational-level influences shape such employee discretionary behaviors in the workplace (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Carmeli et al., 2007). What is particularly lacking in the extant literature is an understanding of the “the mechanisms through which various personal and contextual antecedents influence employee green behavior, the conditions under which the antecedents are particularly influential…” (Norton et al., 2015, p. 114).

This research aims to reveal how socio-psychological mechanisms through organizational-level influences translate into employee involvement in pro-sustainability behaviors. We draw and expand on recent developments in applications of ethical theory; these developments offer an alternative normative foundation for moral decision-making that is grounded in an ethic of care (Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012) and studies that point to the power of care and compassion within organizations (Bolino, Hsiung, Harvey, & LePine, 2015; Kahn, 2005; Lilius et al., 2008; Mitchell & Boyle, 2015; Rynes, Bartunek, Dutton, & Margolis, 2012; Snoeren, Raaijmakers, Niessen, & Abma, 2016; Watkins et al., 2015). However, this theoretical lens has yet to be explored in relation to sustainability within organizations, and we suggest here that an ethic of care (EoC) perspective may inform theory and research of sustainability. Drawing from Lawrence and Maitlis' (2012) research, we suggest that examining the contribution of an organizational EoC to sustainability is potentially fruitful for a number of reasons. First, an EoC perspective responds to limitations of justice-based perspectives to understanding engagement and behavior in relation to sustainability, especially by emphasizing the emotional rather than the rational motives for moral reasoning and behavior (Held, 1990), and the importance of context, capacity, and situation to evaluating morally appropriate conduct (Held, 2005; Noddings, 2003). Second, an EoC perspective is well suited to informing sustainability because the complexity and multi-dimensionality of sustainability means that its achievement is not susceptible to simple universal rules and principles, whereas an EoC reflects a “concern about how to fulfill conflicting responsibilities to different people” (Simola, 2003, p. 354). Third, the emphasis on relationships within an EoC perspective, and especially relationships characterized by inequalities of power and position (Noddings, 2003), seems especially well suited to shedding light on how individuals and organizations navigate relationships between traditional economic outcomes and ecological outcomes given the limited agency and capacity to influence the natural environment (Driscoll & Starik, 2004; Jacobs, 1997).

In light of this opportunity, our research aims to enhance our understanding of how employees' perceptions of their organization's ethic of care influence their involvement in sustainability-related behaviors. We advance a micro-foundation lens to the study of the micro-mechanisms that translate an organizational EoC into higher levels of employee involvement in sustainability behaviors. We develop our theorizing that an EoC creates a caring and compassionate organizational system that fuels employees' involvement in workplace sustainability behaviors, both directly and indirectly via enhanced organizational identification and a higher level of satisfaction. We tested this conceptualization in both an experimental and a time-lagged study that allowed us to better understand micro-socio-psychological mechanisms by which an organizational EoC helps enhance employee involvement in sustainability-related behaviors at work. In so doing, we make three significant contributions. First, we propose an alternative conceptual micro-foundation for sustainability within organizations grounded in an EoC and thus draw on distinct normative processes relative to extant research to inform how greater sustainability might be achieved in organizations. Second, we extend the very limited amount of empirical work that has examined the organizational implications of an EoC and contribute the first empirical study that examines the potential of developing caring organizations for sustainability. Third, using two empirical studies we explore how the influence of an organizational EoC on employee sustainability behaviors is contingent on employee organizational identification and affective reaction to organizational sustainability efforts. Thus, we hope to expand research that examines the situational and contextual factors that shape employee sustainability attitudes and behaviors in the workplace.

2 THEORY AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

2.1 An ethic of care and employee involvement in sustainability activities

The EoC perspective emphasizes relationships, people's needs, and the situations and realities in which dilemmas arise as a context for moral judgment and decisions (Gilligan, 1982; Held, 2005; Noddings, 2003; in Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012). Its origins can be traced to feminist moral theory that challenges dominant models of moral maturity, such as Kohlberg's (1969) stages of moral development, which proposes an alternative normative basis for moral decision-making grounded in a “‘care perspective’ that pays more attention to people's needs, to how actual relations between people can be maintained and repaired, and that values narrative and sensitivity to context in arriving at moral judgments” (Gilligan, 1982, quoted in Held, 2005, p. 28). Thus, Lawrence and Maitlis (2012) conclude that an EoC contrasts with other moral perspectives that emphasize rational, universal, principle, or rule-based and impersonal approaches to ethics (Held, 2005), based on “a felt concern for the good of others and for community with them” (Baier, 1987, p. 721).

While organizational behavior research that draws on the EoC perspective has been relatively limited until recently (Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012), there has been a significant growth of interest in organizational research in issues of care and compassion and their relevance to a range of issues and domains in recent years (e.g., Atkins & Parker, 2012; Frost et al., 2006; Kanov et al., 2004; Lilius et al., 2008). The concept of “care” has been examined in Positive Organizational Scholarship (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Frost et al., 2006; Rynes et al., 2012), and studies have established links between care and compassion and organizational commitment (Lilius, Kanov, Dutton, Worline, & Maitlis, 2012), reduced work-based anxiety (Kahn, 2001), improved workplace self-esteem (McAllister & Bigley, 2002), and resilience (Waldman, Carmeli, & Halevi, 2011).

Recent organization theorists have sought to identify pathways to more concretely examine what an ethic of care perspective implies for organizations and organizing, what practices and processes might characterize a caring organization, and what the effects and boundary conditions of a caring organization could be (Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012; Rynes et al., 2012). In particular, research has suggested that relational forms of organizing and structuring an organization might foster more care and compassion in organizations (Gittell & Douglass, 2012). In addition, it suggests that dialogical, discursive, and narrative practices are central to enacting and sustaining caring in an organization; caring, in turn, promotes an “ontology of possibility” where “a team's potency, collective agency, and transcendent hope” are built and cultivated (Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012, p. 653). These studies have begun to shed light on care and compassion as situated social and organizational practices (Dutton, Worline, Frost, & Lilius, 2006; Jacques, 1992; Liedtka, 1996; Tronto, 1993; Worline & Dutton, 2017) that take a wide range of specific forms including constructing organizational narratives to support the development of caring organizational cultures (Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012), involving, and practicing open dialogue with employees (Liedtka, 1996) and stakeholder management practices (Wicks, Gilbert, & Freeman, 1994).

In this paper, we extend recent theorizing on the potential role of an organizational EoC in shaping organizational processes and outcomes by examining its role in relation to employee involvement in sustainability behaviors. Consistent with prior research on caring in organizations (Kahn, 1993; Lee & Miller, 1999; Liedtka, 1996; Wicks et al., 1994), we conceptualize EoC as an organization-level construct concerned with an organization's “‘deep structure’ of values and organizing principles centered on fulfilling employees' needs, promoting employees' best interests, and valuing employees' contributions” (McAllister & Bigley, 2002, 895). As such, an EoC captures all policies, practices, and behaviors of an organization that aim to advance employee satisfaction and well-being (Lee & Miller, 1999; McAllister & Bigley, 2002), including employee pro-active approaches to practice in areas such as training, development, and informal dialogical practices that signal intrinsic care and concern for employees (Houghton, Pearce, Manz, Courtright, & Stewart, 2015; Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012; Rynes et al., 2012). As such, an EoC encompasses a range of practice and behaviors united by the “firm's intent to ‘go the extra mile’ in treating its employees well” (Bammens, 2016, p. 246), however motivated or manifested.

Organizational or corporate sustainability is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, whose conceptualization and measurement has been contested in much prior research (see Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010). Generally, research has tended to conceptualize organizational sustainability in relation to limiting ecological or environmental harm, though social and community factors have also been emphasized in more recent research. Significantly, previous research has acknowledged the challenging nature of achieving improved organizational sustainability and highlights the complex nature of doing so. For example, while some sustainability practices, such as eco-efficiency drives, might be “no brainers” (Salzmann, Ionescu-Somers, & Steger, 2005, p. 33), the environmental, economic, and social impacts of most sustainability practices are characterized by a need for significant up-front investment and highly uncertain returns and impacts (Marcus, Shrivastava, Sharma, & Pogutz, 2011). Moreover, there is a realization that becoming more sustainable requires significant efforts across an organization's sites, processes, value chains, product design teams, and individual employees (Fey & Furu, 2008; Gulati, Lawrence, & Puranam, 2005; Russo & Harrison, 2005). Consequently, sustainability can be achieved through collaborative efforts and involvement on the part of the employees in the organization (Gittell, Seidner, & Wimbush, 2010; Ramus & Steger, 2000; Siemsen, Balasubramanian, & Roth, 2007). The distributed nature and causes of organizational sustainability therefore necessitate improvements across the entire organization.

Reflecting the varied nature of organizational sustainability, a wide range of employee behaviors play a role in promoting or reducing sustainable outcomes (Ones & Dilchert, 2012). Recent literature has distinguished between “required” or “task-based” sustainability behaviors (Bissing-Olson et al., 2013; Norton et al., 2015) such as complying with organizational policies, changing work practices to select more sustainable alternatives, and creating sustainable products, services, and processes, and “voluntary” aspects of employee sustainability behavior, such as prioritizing environmental interests, initiating environmental programs and policies, lobbying and activism, and encouraging others to behave more sustainably.

Nevertheless, a key question concerns the way in which an EoC in an organization fosters greater employee involvement in sustainability behaviors. We theorize that EoC elicits employees' involvement with organizational sustainability-related behaviors through the lens of social identity theory (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Tajfel & Turner, 1985). Prior research has examined the impacts of caring on various organizational attitudes and behaviors using various theoretical perspectives including social exchange theory (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002), self-determination theory (Bammens, 2016), and emotional contagion (Barsade & O'Neill, 2014), among other perspectives. We build on social identity theory to theorize regarding EoC and employee involvement in sustainability both because social-identification has been shown to relate to employee attitudes to sustainability in prior research (Berens, Van Riel, & Van Rekom, 2007; Folkes & Kamins, 1999; Handelman & Arnold, 1999), as well as because narrower conceptual explanations regarding how caring shapes employee attitudes and behaviors, such as reciprocity and emotional attachment, do not fully account for the association between organizational care and employees' pro-sustainability attitudes and behaviors.

We posit that EoC promotes greater employee involvement in sustainability behaviors for at least three reasons. First, an EoC signals that the organization's commitment to sustainability is authentic, thus reinforcing employee engagement with such practices. Social psychology research has shown that wider employee evaluations of organizational characteristics shape how employees interpret and respond to CSR activities because they influence whether such activities are perceived as authentic reflections of a firm's commitment to pro-sociality (Berens et al., 2007; Folkes & Kamins, 1999; Handelman & Arnold, 1999). Second, an EoC involves dialogue and employee involvement and instills a sense of meaningfulness such that caring for the environment and society helps satisfy people's need to feel part of a greater effort to make a positive change (Spreitzer & Sonenshein, 2004). Third, an EoC entails an environment in which there is a high level of inclusiveness that embraces diversity and builds greater attention to others' concerns and needs (Shore et al., 2011).

2.2 An ethic of care and identification with an organization

Research concerned with employee responses to organizational policies, practices, strategies, and outcomes has often drawn upon social identity theory (Haslam, 2004; Van Dick, 2004; Van Dick et al., 2004). Social identity theory (Hogg & Abrams, 1988; Tajfel & Turner, 1985) sees individual identities as being importantly shaped by the groups (organizations, categories, etc.) of which an individual is a member. In that sense, an individual's identity reflects those groups that he or she is, or is not, a member of and the “individual is argued to vicariously partake in the successes and status of the group” (Ashforth & Mael, 1989, p. 22), as well as other benefits (e.g., emotional support) vital for one's self-conception. Lastly, individuals are understood to have “a basic need to see themselves in a positive light in relation to relevant others (i.e., to have an evaluatively positive self-concept), and that self-enhancement can be achieved in groups by making comparisons between the in-group and relevant out-groups in ways that favor the in-group” (Hogg, Terry, & White, 1995, p. 260).

Organizational identification (OID) refers to “a cognitive linking between the definition of the organization and the definition of the self” (Dutton, Dukerich, & Harquail, 1994, p. 242), or “a perceived oneness with an organization and the experience of the organization's successes and failures as one's own” (Mael & Ashforth, 1992, p. 103). Much of the work on organizational identity builds on the conceptualization postulated by Albert and Whetten (1985) who defined OID as that which is central, enduring, and distinctive within the organization. Thus, OID arises when employees see an organization's essence as self-defining (Ashforth et al., 2008; Haslam, 2004), and OID reflects the “the degree to which a member defines him- or herself by the same attributes that he or she believes define the organization” (Dutton et al., 1994, p. 239).

We suggest that an EoC positively influences OID because it strengthens two key processes that are associated with social identification, namely, uncertainty reduction and self-enhancement (Hogg & Terry, 2000). Bauman and Skitka (2012) built on Hogg and Terry (2000) to develop a conceptual model of the way in which organizational ethics, conceptualized as corporate social responsibility (CSR), shape employee perceptions and psychological responses to organizations. They identified four psychological processes by which CSR supports stronger organizational identification among employees by (1) reassuring employee concerns regarding safety and security, (2) providing positive distinctiveness and enhanced social identity, (3) symbolizing commitment to important values and engendering a sense of belongingness, and (4) adding meaning and a sense of purpose at work (Bauman & Skitka, 2012, p. 3). This is consistent with recent work in psychology that examines the role of organizational ethics in strengthening OID. May, Chang, and Shao (2015) proposed a new construct termed moral identification which is “defined as the perception of oneness or belongingness associated with an organization that exhibits ethical traits (e.g., care, kindness, compassion)” (p. 682).

Drawing on social identity theory, we specify two processes through which an EoC augments OID: (1) by meeting employees' basic psychological needs and reducing uncertainty and (2) by reinforcing employee's self-perceptions via enhanced external organizational esteem and status. Research on caring in organizations has highlighted a number of ways in which caring attributes of organizations (high employee involvement, concern and support for employees, etc.) support employees' psychological needs for belongingness and relatedness. Caring, and the other-centered nature of caring organizations, shapes individuals' concepts of self because people draw inferences about themselves from how others (individuals, groups, and organizations) treat them (Tyler, Kramer, & John, 1999). Through this, caring organizational practices promote employee perceptions of self-worth and value (Worline & Dutton, 2017). Organizational care promotes employees' feelings of relatedness (Bammens, 2016) and well-being. Moreover, a body of empirical evidence suggests that employees hold broadly pro-social values and seek these values to be mirrored in the organizations they work for (Jones et al., 2016). Thus, an EoC promotes OID among employees by promoting employees' sense of well-being, safety, belongingness, and relatedness.

A second process by which EoC promotes OID is via the concept of construed external image (Dutton et al., 1994) or perceived external prestige (Smidts, Pruyn, & Van Riel, 2001), which captures employee perceptions regarding external actors' view of organizations (Dutton et al., 1994). A considerable amount of research has found evidence that perceived external prestige is positively related to OID (Mael & Ashforth, 1992; Smidts et al., 2001). There are a number of strands of research that suggest that caring attributes in organizations generate significant status and esteem for organizations which is likely to enhance OID. Research shows that people are attracted to organizations with caring, honest, pro-social attributes, often termed the “boy scout” personality in such research (Slaughter, Zickar, Highhouse, & Mohr, 2004). Others showed that social organizational performance may be more powerful then economic performance in enhancing one's attachment to the organization (Carmeli, 2005). Research also indicated that more socially responsible companies are highly attractive to prospective employees (Greening & Turban, 2000; Turban & Greening, 1997). Given that an EoC encompasses a range of caring practices, policies and structures that seek to promote employee well-being, fairness, engagement and involvement, these studies suggest that an EoC is likely to be externally recognized and positively evaluated in ways that enhance the identification employees develop towards their organization. Thus, we suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.There is a positive relationship between an organizational EoC and employees' identification with their organization.

3 AN ETHIC OF CARE AND AFFECTIVE REACTION TOWARDS ORGANIZATIONAL SUSTAINABILITY

We also suggest that an organizational EoC is likely to shape individuals' affective reaction towards organizational sustainability. We use the conceptualization of Wageman, Hackman, and Lehman (2005) who originally discussed individuals' affective reaction to a team and its work (p. 388) and use it to refer to one's general satisfaction with the organization's care for sustainability issues and the motivation to follow and strengthen the organization's sustainability values. As such, by affective reaction towards organizational sustainability, we capture both general satisfaction and internal motivation of the employees.

People seek to find meaning in a place they spend many hours every week. A sense of meaningfulness can derive from both belonging to a particular social group but also from the work one does (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003). When employees believe that organizational values, norms, and practices fit their own, they develop a higher level of satisfaction as their need to satisfy what is meaningful for them has been achieved. Second, employees aim to strike a balance between the “prototypical(ity) of the(ir) group” (Hogg & Hardie, 1992; In: Stets & Burke, 2000, p. 226) and their uniqueness as elaborated in self role-based identity theory (McCall & Simmons, 1978). When an organization enacts an EoC, it shapes a space for members to open up and develops greater attention to others' needs. The appraisal theory of emotions suggests that people develop emotions based on the ways they interpret situations they experience (Roseman, Spindel, & Jose, 1990; Smith & Ellsworth, 1985). Following this line of theorizing, we suggest that when employees sense that the organization is engaged in activities that contribute to improving societal and environmental issues and strengthening its relationships with the community, they are likely to see themselves as part of this effort and develop a sense of satisfaction with this set of sustainability activities. Third, drawing on the literature on growth need satisfaction (Alderfer, 1972), we reason that when organizations are perceived to be acting to make a positive influence on the whole system, employees are likely to develop a sense of fullness as human beings, which makes them more content (Schneider & Alderfer, 1973). Hence, the following hypothesis is suggested:

Hypothesis 2.There is a positive relationship between an organizational EoC and employees' affective reaction towards organizational sustainability.

We also theorize on the intervening role of identification with an organization. Research suggests that identification helps people to satisfy their basic need to belong and avoid feelings of being alienated. As Van Knippenberg and Van Schie (2000) noted: “through identification, ‘the job’ becomes in a sense part of the self...(and) it may be expected to add to feelings of job satisfaction because people tend to evaluate attitude objects associated with the self positively (cf. Beggan, 1992)” (p. 141). That is, when individuals' self-concept is closely aligned with what the organization represents and stands for, their positive subjective psychological state and experience (e.g., job satisfaction) are likely to be higher (Van Dick, van Knippenberg, Kerschreiter, Hertel, & Wieseke, 2008).

Gioia, Price, Hamilton, and Thomas (2010) investigated the processes involved in the formation of an organizational identity using an interpretive, insider–outsider research approach and concluded that internal and external, as well as micro and macro factors affect the forging of an organizational identity. For example, the study by Rothausen, Henderson, Arnold, and Malshe (2015) utilized a sensemaking perspective to explore the reasons for employees' decision to quit or stay in the organization and found that perceived threat to identity and well-being across life domains leads to varying levels of psychophysiological strain, coping with threat and strain, often in escalating cycles eventually resulting in turnover. Mesmer-Magnus, Asencio, Seely, and DeChurch (2015), on their part, found that whereas team identity fully mediates the relationship between organizational identity and team affective constructs (i.e., aspects of team functioning are not instrumental to the fulfillment of organizational identity), organizational identity uniquely and directly affects cooperative team behavior and team performance. Exploring the differential relationships of organizational and work group identification with employee attitudes and behavior, Van Dick et al. (2008) found that in cases of positive overlap of identifications (i.e., high work group and organizational identification), employees report higher levels of job satisfaction. When people identify with a social group, they satisfy their need to belong and develop feelings of social inclusion, which is likely to generate affective reaction to the work. Further, research of meaningfulness suggests that people develop a sense of meaningfulness through belonging to a social group (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003), which in turn can engender positive psychological experiences (Cohen-Meitar, Carmeli, & Waldman, 2009). Extending this logic, Johnson, Morgeson, and Hekman (2012) examined two different forms of social identification (cognitive and affective) in organizational settings and found that affective identification provides incremental predictive validity over and above cognitive identification in the prediction of organizational commitment, organizational involvement, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Thus, we posit that an EoC is likely to augment a sense of identification which helps develop affective reactions towards the organization's sustainability values and efforts. Thus, we suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.There is a direct and indirect relationship, through employees' identification with their organization, between an organizational EoC and employees' affective reaction towards organizational sustainability.

3.1 Organizational identification, affective reaction towards organizational sustainability, and employee involvement in sustainability-related behaviors

Individuals' involvement in specific behaviors can take many forms. In the context of work organizations, we expand on the concept of job involvement which is defined as “a belief descriptive of the present job that tends to be a function of how much the job can satisfy one's present needs” (Kanungo, 1982, p. 342). In the context of this study, we define involvement in sustainability-related behaviors as the extent to which one makes an effort and acts to enhance organization-related sustainability actions. From an identity theoretical lens, our theorizing suggests that an EoC is interpreted by members with regard to the extent to which members think that the organization developed an identity of EOC (perceived organizational identity), and when the same attributes are central to them, it is likely that an organizational identification will be developed (see Dutton et al., 1994). When they are aligned with their own beliefs, their positive emotional state or response (see Locke, 1976) is likely to increase, and this sense of satisfaction is likely to channel more energy and prompt them to devote further efforts that are likely to reinforce this identity; in our case, EoC is likely to lead, through identification and satisfaction, to greater involvement in sustainability-related activities. This logic leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.There is an indirect relationship (serially through identification with the organization and affective reaction towards organizational sustainability) between an organizational EoC and employees' involvement in sustainability-related behaviors.

4 STUDY 1, METHOD

4.1 Sample and procedure

The participant pool was made up of 218 respondents recruited through Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk; Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011). Participation was limited to full-time employees in the USA (we excluded 32 participants who reported that they were not currently employed), resulting in a sample of 186 participants who had completed fewer than 50 surveys through this platform. The participants were compensated with $1. One hundred and nineteen participants were women (54.6 percent). The participants' educational level ranged from high school degree (19.3 percent), BA (65.6 percent), MA (12.4 percent) to PhD (2.8 percent). The average age of the participants was 31.93 (SD = 10.17), and the mean tenure with their employer/organization was 3.73 (SD = 4.45). The sample was ethnically diverse: 78 percent were European American, 5.5 percent Hispanic, 6.9 percent African-American, 5.5 percent Asian, 0.9 percent Middle Eastern, and 3.2 percent reported other ethnicity. Employment status was verified at the beginning of the survey. All participants completed the survey in less than 15 minutes.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions of organizational EoC (high EoC group, low EoC group, and control group). After providing their consent, two groups were asked to read their assigned scenario in which the organization acted with a high or low level of EoC, and the third (control) group was simply given a short description of an organization identical to the one that appeared in the first sentences of each condition but without any reference to the subject matter (i.e., EoC; Appendix B). They were asked to reflect on the scenario, after which they filled in manipulation check questions and completed the other parts of the questionnaire. The respondents completed a filler task between the three parts of the survey (independent, mediation, and dependent variables), such as describing a recent movie they had seen and or the place they went to on their last vacation.

4.2 Measures

All measurement items appear in Appendix B. Responses were all on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very large extent.

4.2.1 Organizational ethic of care

Following Lawrence and Maitlis (2012), we constructed a six-item measure that assessed the extent to which an organization is environmentally ethical and cares for creating a healthier and sustainable environment and community. Factor analysis results indicated a one-factor solution that explained 81.86 percent of the variance and had eigenvalues of 4.91 (α = .95). To construct this scale items, we asked a group of graduate students to assess the extent to which each item adequately reflected the essence and substance of the concept of EoC. Following this process, we also ran a pilot study on 158 full-time employees. Sixty-three of the participants were women (39.9 percent), and their average age was 31.94 (SD = 8.41). We sought to further explore the construct validity and factor-analyzed the EoC items and six items from Lindgreen, Swaen, and Johnston's (2009) research that assessed CSR (philanthropic activities). The results indicated a two-factor solution with one factor (EoC) that accounted for 50.29 percent of the variance and a second factor [CSR (philanthropic activities)] that accounted for an additional 18.83 percent of the variance. None of the factor items exhibited cross-loadings >0.24 (except for one item that had a cross loading of 0.34). This provides additional evidence for the validity of the construct.

4.2.2 Employee affective reaction towards organizational sustainability

We adapted four items from the study of Wageman et al. (2005) that originally aimed to assess individuals' affective reaction to a team and its work (p. 388). We focused on two dimensions—internal motivation and general satisfaction—and adapted the items such that they captured motivation for and satisfaction with organizational sustainability. Factor analysis results indicated a one-factor solution, which explained 73.67 percent of the variance, and had eigenvalues of 2.95 (α = .79).

4.2.3 Employee involvement in organizational sustainability

We used nine items from the Kanungo (1982) scale, which originally assessed people's involvement in their job. We adapted the scale items to specifically assess involvement in organizational-related sustainability activities. Factor analysis results indicated a one-factor solution, which explained 73.99 percent of the variance, and had eigenvalues of 6.66 (α = .95).

4.2.4 Controls

We controlled for employee age (in years), gender (female = 1), educational level [high school, BA, MA, and PhD], and tenure in the organization (in years).

5 STUDY 1, RESULTS

5.1 Manipulation check

The manipulation of an organizational EoC was successful. Participants in the low EoC condition rated the care of their organization as lower (M = 2.68, SD = 1.10) compared with participants in the control condition (M = 3.19, SD = 1.15) and participants in the high EoC condition (M = 3.23, SD = .90), F(2, 183) = 5.31, p = .006, η2 = .055. The high EoC condition did not differ from the control condition, p = .84.

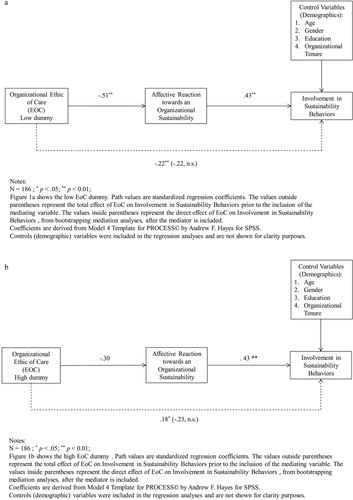

5.2 Indirect relationship analysis

We tested whether affective reaction towards organizational sustainability (AROS) mediated the effect of EoC on employee involvement in organizational sustainability (IVL), using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2012; Hayes & Preacher, 2014). This program provides a regression-based analysis for mediation models (see Model 4 in PROCESS). It also provides standard tests and bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs), which here were based on 10 000 samplings, for individual regression coefficients and for indirect effects. We constructed two dummy variables: EoC (low) with the control condition as the reference group (control = 0), and EoC (high) with the control condition as the reference group (control = 0). We controlled for the demographic variables of age, gender, education, and organizational tenure. Out of all the control variables, only education was significantly related to IVL. As predicted, for the low EoC versus control comparison, the CI did not include zero (−.59 to −.10) indicating a significant indirect effect through AROS. For high EoC versus control group comparison, the CI did include zero (− .42 to .03; see Table 1 for the separate regression analyses). The findings are illustrated in Figure 1.

| Regression | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression 1: EoC on IVL | ||||

| Low EoC dummy | −.223 | .170 | −2.62 | .010 |

| High EoC dummy | .182 | .169 | −2.12 | .035 |

| Age | −.038 | .007 | −.480 | .632 |

| Gender | .001 | .137 | .009 | .992 |

| Education | −.191 | .107 | −2.64 | .009 |

| Tenure | −.065 | .017 | −.819 | .414 |

| Regression 2: EoC on AROS | ||||

| Low EoC dummy | −.508 | .170 | −2.98 | .003 |

| High EoC dummy | −.299 | .169 | −1.76 | .078 |

| Age | −.003 | .007 | −.514 | .608 |

| Gender | −.183 | .137 | −1.33 | .184 |

| Education | −.081 | .107 | −.757 | .449 |

| Tenure | −.025 | .016 | 1.54 | .124 |

| Regression 3: EoC and AROS on IVL | ||||

| Low EoC dummy | −.224 | .156 | −1.42 | .155 |

| High EoC dummy | −.228 | .154 | −1.48 | .82 |

| AROS | .433 | .067 | 6.44 | .001 |

| Age | −.002 | .006 | −.284 | .777 |

| Gender | .080 | .124 | .648 | .518 |

| Education | −.247 | .096 | −2.56 | .011 |

| Tenure | −.024 | .015 | −1.64 | .103 |

- Note: EoC, ethic of care; AROS, affective reaction towards organizational sustainability; IVL, involvement in organizational sustainability.

6 STUDY 2, METHOD

6.1 Sample and procedure

Study 2 was designed to elaborate the research model and further examine the relationships between EoC, AROS, and IVL. In particular, we sought to examine whether a social identity perspective can inform our model by exploring whether OID serves as an intervening mechanism that connects EOC and AROS and thereby influences IVL.

To this end, we used time-lagged data collected from part-time students who reported on at least 10 working hours in a week. They have been employed in a variety of organizations and sectors [educational, service, knowledge-intensive, and more traditional settings (e.g., food chains]. We believe that this variety enhanced the generalizability of the findings. The participants were recruited through a behavioral lab in a large university and were given course credit points as specified by the school's pre-structured scheme. We asked the participants to complete each part of the survey with a lag of about 10 days to separate responses on the control (Time 1), independent (Time 1), mediation (Time 2), and dependent variables (Time 3), such that response bias associated with responses at a single point in time would be alleviated.

Overall, we received usable surveys (excluding 59 surveys for which we had only partial data due to incomplete questionnaires) from 110 respondents. Sixty-three participants were women (57.3%), and the vast majority was studying for a college degree (97 percent), with about 3 percent having MA degree. The average age of the participants was 22.84 (SD = 2.31), and the mean tenure with their employer/organization was 1.46 (SD = 1.34).

6.2 Measures

All measurement items appear in Appendix B.

6.2.1 Organizational ethic of care

As in Study 1, we used the same measurement items (α = .93).

6.2.2 Identification with the organization

We used three items from the Smidts et al. (2001) scale of organizational identification. Factor analysis results indicated a one-factor solution (α = .81).

6.2.3 Employee affective reaction towards organizational sustainability (AROS)

As in Study 1, we used the same scale items adapted from Wageman et al. (2005; α = .84).

6.2.4 Employee involvement in organizational sustainability

As in Study 1, we used the same scale items adapted from Kanungo (1982). (α = .96).

6.2.5 Controls

We controlled for employee age (in years), gender (female = 1), educational level, tenure in an organization (in years), and employee pro-environmental behaviors (EPB), which was assessed using three items from Robertson and Barling (2013; α = .67). These data were collected at Time 1.

7 STUDY 2, RESULTS

We performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess whether our four-factor structure fit the data. CFA results for the four-factor structure had a good fit with the data (χ2 203) = 311.5, p < .01, CFI = .945, TLI = .938, RMSEA = .07). We then compared it to a three-factor structure where OID and AROS collapsed onto one latent variable, whereas EoC and IVL were collapsed onto two different latent variables. The results indicated a poorer fit with the data (χ2206) = 419.7, p < .01, CFI = .892, TLI = .879, RMSEA = .098). Third, we tested a two-factor structure where EoC, OID, and AROS were collapsed onto one latent variable and IVL was collapsed on a different latent variable (χ2208) = 525.2, p < .01, CFI = .840, TLI = .822, RMSEA = .118). Finally, we tested a one-factor structure, and the results indicated a poor fit with the data (χ2209) = 895.4, p < .01, CFI = .653, TLI = .617, RMSEA = .174).

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the research variables are presented in Table 2.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (1 = Female) | — | — | — | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 22.83 | 2.31 | −.38** | — | |||||||

| 3. Education | 1.25 | .50 | .07 | .09 | — | ||||||

| 4. Tenure with an employer/organization | 1.46 | 1.34 | −.01 | .30** | .02 | — | |||||

| 5. Pro-environmental behaviors | 2.55 | .94 | −.17 | −.04 | .12 | .04 | (.67) | ||||

| 6. Organizational ethics of care | 2.47 | .91 | −.21* | −.04 | .13 | .00 | .24* | (.93) | |||

| 7. Organizational identification | 3.07 | .93 | .00 | −.20 | .23** | −.13 | .32** | .43** | (.81) | ||

| 8. Affective reaction towards organizational sustainability | 2.53 | .88 | −.10 | −.09 | .19 | .02 | .35** | .64** | .58** | (.84) | |

| 9. Employee involvement in organizational sustainability | 1.91 | .85 | .03 | −.19* | .05 | −.04 | .25** | .20* | .16 | .38** | (.96) |

- Note: N = 110; two-tailed test; reliabilities are in parentheses on the diagonal.

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

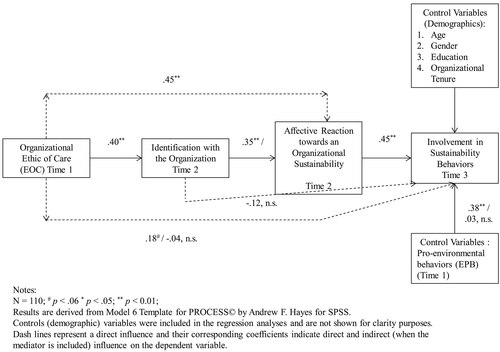

As in Study 1, we tested our model and hypotheses using the computer program PROCESS (Hayes, 2012). This program provides a regression-based analysis for serial mediation models (cf. Model 6 in PROCESS). It also provides standard tests and bootstrap CIs, which here were based on 10 000 samplings, for individual regression coefficients and for indirect effects.

PROCESS makes it possible to test a model that includes multiple mediators operating serially by estimating the three stages in a sequential manner, that is, in the first stage of the model, the EoC → OID link is estimated first; in the second stage, the OID → AROS link is estimated with EoC included as a predictor, followed by the third stage in which the AROS and IVL link is tested with EoC and OID included as predictors. Table 3 summarizes the model results for the relationships of EoC → OID → AROS → IVL. The bootstrap CIs were based on 10 000 samplings. In all of the analyses, we included employee gender, age, tenure in the organization, education, and EPB as control variables.

| B130 | Organizational identification (OID) | Affective reaction towards an organizational sustainability (AROS) | Employee involvement in organizational sustainability (IVL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variable | β | SE | 95% bias corrected bootstrap CIb | β | SE | 95% bias corrected bootstrap CIb | β | SE | 95% bias corrected bootstrap CIb |

| Constanta | 3.34 | .98 | (1.41, 5.28) | .45 | .79 | (−1.11, 2.01) | 2.62 | 1.00 | (.64, 4.62) |

| Organizational ethics of care (EoC) | .40** | .09 | (.22, .58) | .45** | .08 | (.30, .60) | −.04 | .11 | (−.27, .18) |

| OID | .35** | .07 | (.20, .50) | −.12 | .10 | (−.32, .09) | |||

| AROS | .45** | .13 | (.20, .70) | ||||||

| R2 | .26** | .53** | .18** | ||||||

- Note: N = 110.

- a Coefficients are unstandardized.

- b Tests were conducted using PROCESS (Hayes, 2012).

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

As shown in Table 3, with OID as the dependent variable, the regression coefficient for EoC was significant (.40, p < .01). The bootstrap CI for this coefficient was (95% CI [.22, .58]), indicating a reliably significant effect.

At the second step, in which AROS was regressed on OID, the coefficient was significant (.35, p < .01), and the bootstrap CI for this coefficient was (95% CI [.20, .50]). However, the relationship for EoC and AROS was statistically significant (.45, p < .01), and its bootstrap CI was (95% CI [.30, .60]). This indicates that there was a direct effect of EoC on AROS. In the third step in which IVL was regressed on EoC, OID, and AROS, only AROS had a significant coefficient (.45, p < .01) and a bootstrap CI that did not include zero (95% CI [.20, .70]). This supports our mediation hypothesis that EoC indirectly influences IVL, through OID and AROS. The indirect effect of EoC → OID → AROS → IVL was .64 (Booth SE = 0.0262; BootLLCI = .0258; BootULCI = .1368. The findings are illustrated in Figure 2.

8 DISCUSSION

The goal of this paper was to develop a conceptualization of the micro-foundations of organizational sustainability grounded in an Eoc perspective and to provide an initial empirical examination of the process by which caring and compassionate workplaces might foster employees' involvement in activities that are likely to improve organizational sustainability. Overall, the findings of these two studies demonstrate the importance of an organizational EoC in motivating employees to become involved in sustainability-related behaviors in the workplace.

8.1 Theoretical implications

Our research contributes to the literature in several ways. First, the EoC perspective we draw on points to “organizations as potential caregiving and care-supporting systems” (Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012, p. 644) that care for their surroundings (i.e., constituencies and their relationships). Our research shows why this perspective, which offers a unique outlook that goes beyond the rule-based duty approach and complements the justice theory (Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012), can inform research and theory on organizational sustainability by explaining why caring and compassionate organizations can drive their employees' involvement in sustainability-related behaviors. While caring and compassion in organizational life have been a key subject of inquiry in recent years (Dutton, Workman, & Hardin, 2014), this framework has not been directly applied in studies of organizational sustainability and CSR. Our work provides new insights about the power of caring organizations in shaping employees' perceptions and involvement in sustainability-related activities. This is important as it combines both organizational architectures and individuals' actions that are likely to help build a greater sustainable whole.

Second, research on sustainability has often taken a macro-to-macro level approach (e.g., Berrone et al., 2010; Reid & Toffel, 2009; Walls et al., 2012), but scholars have encouraged further studies on the importance of employees in improving organizational sustainability (Norton et al., 2015). We advance theory and research by adopting a macro-to-micro conceptual approach (Carmeli et al., 2007) and integrating a micro-foundation perspective (Foss, 2011; Powell et al., 2011) to explain the micro socio-psychological mechanisms through which this influence process unfolds (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). Specifically, our findings help explain why and how an EoC at the organization level translates into employees' involvement in activities that can benefit organizational sustainability efforts and goals.

Finally, our study also contributes to social identity theory and particularly to research on OID. We show that identification with an organization is a key socio-psychological mechanism and expand theorizing that explains why an EoC can enable people to both satisfy their need to belong and maintain their uniqueness (McCall & Simmons, 1978) and how this translates into a positive affective reaction (i.e., satisfaction; Schneider & Alderfer, 1973), and hence involvement in sustainability behaviors.

8.2 Practical implications

Our results may have some important practical implications for organizations and their managers. First, they provide some evidence for the notion that an EoC enacted by small steps towards a healthy and sustainable community can drive members to develop a higher level of attachment to the organization. This is vital because recent reports indicate that employees tend to voluntarily leave their organizations after ever shorter periods of time. Building a strong identity depends on the ability of the organization to harness members' belief in the values, norms, and practices it attempts to maintain over a long period of time. This poses a key challenge to managing organizations which on the one hand strive for stewardship and on the other depend heavily on their members who act as the real agents of these values.

Clearly, organizations need to develop mechanisms for recruiting and developing members who can act as ultimate and authentic agents of the EoC the organization stands for and strive to demonstrate this in day-to-day activities. This requires a more in-depth process than simply posting a set of values and objectives on the organization's intranet portal and expecting employees to follow them. Instead, managers need to lead by example and build work environments in which an EoC is embedded in work processes naturally. These practices can be further developed, refined, and reconfigured by employees who appreciate these values and engage in strengthening and sustaining the identity of the organization and by implication defining their self.

Employee involvement is not only important for reinforcing sustainability values and practices within the organization but also for disseminating these norms and activities to influence the industry such that other players can adopt them to create a more viable community. For example, when an organization develop these values and norms and engage others in this set of values, this process can reshape the ways the entire community approaches sustainability issues. In many ways, it can create a reinforcing process in which sustainability guides all actors in the value chain and as a result shapes and redefine the identity of a community and its sub-groups.

In addition, senior executives, through press releases and media channels, can convey the message of an EoC to all stakeholders. However, for certain stakeholders, employees may be able to make a more substantial difference because they engage on a daily basis with customers, suppliers, regulators, and others, and more authentically demonstrate how these values define what the organization does and does not do. In order to build such missionary zeal among employees, organizations must understand that employees not only seek to be part of a system that cherishes this set of values and norms but also help them enact it such that a sense of meaningfulness is derived from the day-to-day work they do. This can be performed through various activities. For example, acts of appreciation that recognize stewardship behaviors (e.g., sharing an anecdotal story of an employee who demonstrated care for the environment) signal a message of worth that not only strengthens the level of attachment but also harnesses colleagues to follow and act responsibly. We advocate the idea that small acts can make a significant difference. This is because they are like the “glue that puts together” the ingredients and components that make up an organization that believes in and practices an EoC.

8.3 Limitations and future research directions

Beyond the future lines of enquiry signaled by our comments concerning the managerial and conceptual opportunities suggested by our study, some future lines of enquiry flow directly from the limitations of the present study. In particular, our study is a first step towards addressing the macro-to-micro issues and integrating a micro-foundation perspective into the study of sustainability. At the same time, there is much to be done to more fully conceptualize, and subsequently empirically examine, an EoC approach to addressing sustainability challenges. EOC is an emergent concept, and despite our evidence, we need further studies that validate the measure employed here and replicate our findings. In addition, it would be worth examining how practices that build and sustain an EoC within organizations including narrative practices, positive organizational psychology, compassionate approaches to leadership, and forgiveness, among others, shape and influence attitudes and behaviors in relation to sustainability. For example, we can only speculate whether the design of an organization in its early days can influence the development of an EoC or how CEO leadership influences the level of an EoC and the ways the latter is enacted in day-to-day activities. Moreover, further conceptual and empirical research into the boundary conditions that define the circumstances and contexts in which an EoC promotes pro-sustainability attitudes and conduct, the contingencies that intervene in such processes, and examinations of the complementarities and tradeoffs between caring and compassionate practices, and alternative forms of organizational ethical climates would also be very fruitful lines of enquiry.

In spite of our experiment study and time-lagged data, caution should be exercised when attempting to draw causal inferences. In addition, although we believe that people's involvement is more subjective because there can be many forms, some of which are invisible, of engaging in particular behaviors, future studies should integrate perceptions of peers and supervisors. Although we used time-lagged data in Study 2, one should cautiously interpret the findings as both mediation mechanisms were assessed at the same point in time. Furthermore, we did not examine behaviors per se because we were mainly interested in the motivational process. However, scholars can integrate actual behaviors and examine when involvement translates or not into behavioral outcomes. We also examined employees' perceptions of an organizational EoC; it may be useful to examine other levels such as direct supervisors' and senior leaders' EoC. For example, leader EoC may be more likely to directly influence people's identification with their leader (i.e., relational identification). Finally, studies could explore how an EoC influences employees and other constituencies' well-being and economic welfare over time.

9 CONCLUSION

This paper presented, through two studies, an initial exploration of the role of an organizational EoC and micro-mechanisms that translates this identity into employee involvement in sustainability-related behaviors. In so doing, we hoped to contribute both to emergent research on the ways in which an EoC shapes attitudes and behaviors within organizations and cultivate a new research agenda on organizational sustainability that builds upon an EoC perspective. Our findings indicate that an EoC helps shaping employees' positive attitudes (higher levels of identification with the organization and affective reaction towards the organizational sustainability) and that these mechanisms foster them to be more involved in sustainability-related activities. Taken together, our theoretical development and empirical analyses open up novel future opportunities to better understand the micro-foundations of organizational sustainability by building upon moral theorizing of care.

10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the guest editor and three anonymous reviewers for their constrictive and helpful comments and suggestions. We also benefited from the helpful feedback from participants of the 2016 SEE conference in which we presented an earlier version of this work. We thank Anna Dorfman for her assistance with the analyses.

Appendix A: Manipulation of an Organizational Ethic of Care

A.1. High Level of Ethic of Care

Please read the following text.

Imagine that you have been working at Xbonix, a fictitious company that develops advanced solutions in the biotechnology industry. Last month, the company announced that it would contribute 10 percent of its profits to social and environmental efforts in the community. In a press release, the company managers stated: “we feel proud to be able to make this ongoing contribution to help build a more environmentally and socially responsible community. Our credo guides us to make substantial efforts to make our world more sustainable.”

A.2. Low Level of Ethic of Care

Please read the following text.

Imagine that you have been working at Xbonix, a fictitious company that develops advanced solutions in the biotechnology industry. Last month, a rival company announced that it would contribute 10 percent of its profits to social and environmental efforts in the community. A Xbonix employee sent an email via the company internal mail system to inquire: “shouldn't we also do something for the community?” In response, Xbonix's managers sent a signed email stating: “we need to take care of our own interests and those interests alone!”

Appendix B: Measurement Items

| Employee pro-environmental behaviors [source: adapted from Robertson and Barling (2013)] |

| 1. I put compostable items in the compost bin. |

| 2. I put recyclable material (e.g., cans, paper, bottles, and batteries) in the recycling bins. |

| 3. I take part in environmentally friendly programs (e.g., bike/walk to work day, bring your own local lunch day) |

| An organizational ethic of care |

| This organization |

| 1. Cares deeply for environmental issues |

| 2. Cares for a healthy ecosystem |

| 3. Shows genuine concerns for natural resources |

| 4. Demonstrates clear support in efforts aimed to enhance sustainability |

| 5. Acts virtuously for building a healthier community |

| 6. Acts responsibly to remove any potential harms for the environment |

| Identification with the organization [Adapted from Smidts et al. (2001)] |

| 1. I feel strong ties with this organization |

| 2. I experience a strong sense of belonging in this organization |

| 3. I am glad to be a member of this organization |

| Affective reaction towards organizational sustainability (AROS) [adapted from (Wageman et al., 2005)] |

| 1. I feel a real sense of personal satisfaction when this organization does well on sustainability |

| 2. I feel bad and unhappy when this organization has performed poorly on sustainability |

| 3. My own feelings are not affected one way or the other by how well this organization performs on sustainability (reverse-scored item) |

| 4. I enjoy the kind of work done in this organization on sustainability |

| 5. Generally speaking, I am very satisfied with this organization and its approach to sustainability issues |

| Employee involvement in organizational sustainability-related behaviors (IVL) [adapted from Kanungo (1982)] |

| 1. The most important things that happen to me involve the work I do to improve sustainability in this organization |

| 2. I am highly involved personally in improving sustainability in this organization |

| 3. I live, eat and breathe to improve sustainability in this organization |

| 4. Most of my interests are centered around my attempts to improve sustainability in this organization |

| 5. I have very strong ties to my involvement in sustainability in this organization which would be very difficult to break |

| 6. In this organization, most of my personal goals are sustinability-oriented |

| 7. I consider my efforts to improve sustainability in this organization to be very central to my existence |

| 8. In this organization, I like to be absorbed in sustainability issues most of the time |

| 9. The most important things that happen to me in this organization involve my present engagement in sustainability issues |

Biographies

Abraham Carmeli is a faculty member at Tel Aviv University. He received his PhD from the University of Haifa. His current research interests include leadership and top management teams, relational dynamics, learning from failures, and creativity and innovation in the workplace.

Stephen Brammer is a professor and an executive dean of the Faculty of Business and Economics at Macquarie University. He received his PhD in Economics from the University of East Anglia. His current research interests include stakeholder management, environmental management, institutional influences on corporate responsibility, and corporate reputation.

Emanuel Gomes is a senior lecturer (Associate Professor) in International Business and Strategy at the University of Birmingham, Birmingham Business School (UK), and a visiting associate professor at Nova School of Business, Portugal. His research interest is in the areas of M&A, strategic alliances, internationalization of the firm, and product service innovation

Shlomo Y. Tarba is a reader (Associate Professor) in Business Strategy and head of the Department of Strategy & International Business at the Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham, UK. He is a visiting professor in Recanati Business School, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. He received his PhD in Strategic Management from Ben-Gurion University and Masters in Biotechnology degree at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel. His research interests include agility, organizational ambidexterity and innovation, emotions, resilience, cross-cultural management, HRM, and mergers and acquisitions.