Workplace racial/ethnic similarity, job satisfaction, and lumbar back health among warehouse workers: Asymmetric reactions across racial/ethnic groups

Summary

Racial and ethnic minority employees constitute a significant proportion of the U.S. workforce. The literature on demographic similarity in the workplace suggests that the proportion of co-workers who share the same racial/ethnic background (racial/ethnic similarity) can influence job attitudes and employee well-being and that the reactions to racial/ethnic similarity may differ between the racially dominant and subordinate groups. This study applies status construction theory to examine the extent to which racial/ethnic similarity is associated with job satisfaction and lumbar back health among warehouse employees. We surveyed 361 warehouse workers (204 whites, 94 African-Americans, and 63 Latino workers) in 68 jobs in nine distribution centers in the United States. Multilevel analyses indicate that white and racial/ethnic minority groups react differently to racial/ethnic similarity. For job satisfaction, white employees experience higher job satisfaction when they are highly racially/ethnically similar to their colleagues, whereas Latino employees experience higher job satisfaction when they are racially/ethnically dissimilar to others. As for lumbar back health, among Latino and African-American employees, higher racial/ethnic similarity is associated with better lumbar back health whereas for white employees, the association is the opposite. Across all groups, moderate levels of racial/ethnic similarity were associated with the best lumbar back health. Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

The U.S. workforce is becoming increasingly diverse in terms of race and ethnicity. In 2011, 67% of the workforce comprised white, non-Hispanic employees (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012). This proportion is expected to drop to 51% by 2050. In contrast, the proportion of Latino employees is expected to grow from 13% to nearly 25% during the same time span. African-Americans, which currently account for 11% of the U.S. workforce, are expected to increase to 14% of the workforce (Lee & Mather, 2008). As a result, a growing number of white employees will find themselves working with colleagues of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. Conversely, Latinos and African-American employees, traditionally numerical minority groups, will find more colleagues who share the same racial/ethnic background.

Organizational researchers posit that the extent to which employees work with similar others is important for their job attitudes (Riordan & Wayne, 2008; Tsui, Egan, & O'Reilly, 1992; Wharton, Rotolo, & Bird, 2000; Williams & Meân, 2004). Using the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) and similarity attraction paradigm (Byrne, 1971), earlier studies on racial/ethnic similarity have generally reported that higher racial/ethnic similarity is associated with favorable job attitudes such as higher job satisfaction and commitment (Williams & O'Reilly, 1998). More recent reviews, however, have indicated that the findings are less conclusive than previously reported (Joshi & Roh, 2009; Shore et al., 2009), which suggests that the traditional social identity theory and similarity attraction paradigm may be limited. The literature has shifted its focus to the status associated with demographic characteristics to seek a deeper understanding of reactions to demographic similarity among different demographic groups (Chatman & O'Reilly, 2004; Chattopadhyay, Tluchowska, & Gerge, 2004; DiTomaso, Post, & Parks-Yancy, 2007; Reskin, McBrier, & Kmec, 1999).

In the current study, we use the status construction theory (Ridgeway, 1991; Ridgeway, Boyle, Kuipers, & Robinson, 1998) as a framework for examining reactions to racial/ethnic similarity among white, African-American, and Latino warehouse workers. The status construction theory asserts that when groups differ on nominal characteristics such as race or ethnicity and at the same time differ on the level of access to resources, the nominal characteristics then become a marker for status, competence, and worthiness. Ridgeway (1991) used an example of white men being considered worthier than Black men and women of any race. Once consensual beliefs are formed about nominal characteristics, general expectations emerge about those who display the characteristics. Individuals then apply general expectations to specific individuals, which in turn influences their social interactions. Importantly, members of groups with access to fewer resources also come to accept the beliefs and expectations (Pyke, 2010) and may seek association with dissimilar others who have more resources (Chattopadhyay et al., 2004; Fiske, 2002). This clearly contrasts the status construction theory with the social identity theory and similarity attraction.

Applying the status construction theory framework allows us to link racial/ethnic dynamics in the society and in the workplace. That is, we consider the nature of social interactions in the workplace as consequences of racial/ethnic dynamics in the society in general. We focus on three products of status construction: occupational prestige (i.e., jobs held by whites are considered as more prestigious than jobs held by minorities), status contamination (i.e., whites lose status through frequent contacts with minorities), and value threat (i.e., racial/ethnic minorities are concerned that whites may not recognize their value). We will discuss these constructs as potential mechanisms for different reactions to racial/ethnic similarity across different racial/ethnic groups.

Before presenting our arguments, we point out several challenges in studying the complexity of racial/ethnic dynamics in a white-dominant society. Race/ethnicity is deeply intertwined with socioeconomic position and occupational segregation (Cole & Omari, 2003; Tomaskovic-Devey et al., 2006; Williams & O'Reilly, 1998). Racial/ethnic minorities tend to have less education, less desirable jobs, and lower income. For example, more than 50% of assembly-line workers are racial/ethnic minorities, whereas only about 10% of engineers are minorities (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012). These differences between racially dominant and subordinate groups make it difficult to isolate the effect of racial/ethnic similarity from that of material deprivation and other economic inequalities. One way to avoid this confounding is to focus on a single occupation so that socioeconomic position—often defined by income, education, and occupation—is similar across racial/ethnic groups. Another challenge is numerical underrepresentation of racial/ethnic minorities in study samples. Many studies have been conducted in white-collar workplaces with few racial/ethnic minority employees, which makes it difficult to analyze results for minorities (Tonidandel, Avery, Bucholtz, & McKay, 2008). Focusing on an occupation at the lower end of the socioeconomic strata ensures a larger representation of racial/ethnic minority groups.

In addition to these methodological challenges, the current racial/ethnic similarity literature lacks a focus on health as a consequence of racial/ethnic similarity. Persistent health disparities across racial/ethnic groups are a major problem in the United States (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008). Socioeconomic status and physical working conditions both tend to differ by race/ethnicity and thus may be sources of racial/ethnic health disparities (Murray, 2003). Few studies, however, have investigated psychosocial aspects of the job as potential sources of racial/ethnic health disparities (e.g., Hoppe, 2011; Sundquist, Östergren, Sundquist, & Johansson, 2003). Because work is a major determinant of health, examining the workplace psychosocial environment, especially racial/ethnic similarity, may help us better understand racial/ethnic health disparities.

In this paper, we extend the current literature on racial/ethnic similarity by addressing these limitations. We use a single occupation sample, warehouse workers, from workplaces with varying degrees of racial/ethnic diversity. This helps to limit socioeconomic confounding and to ensure sufficient representation of racial/ethnic minorities. In addition to a traditional outcome of job satisfaction, we focus on objectively measured employee health as a function of racial/ethnic similarity.

Racial/ethnic similarity and job satisfaction: asymmetric reactions across racial/ethnic groups

Job satisfaction is a cognitive and affective evaluation of one's working conditions (Brief & Weiss, 2001). It is closely related to organizational commitment and attachment; it also strongly predicts turnover intention and absenteeism (Dormann & Zapf, 2001). Job satisfaction, an antecedent for organizational performance, has been one of the most intensively researched concepts in occupational and organizational psychology.

Several studies have reported different associations of racial/ethnic similarity with job satisfaction and other closely related constructs (i.e., organizational commitment and attachment). White, Latino, and African-American employees in minority-dominant teams were found to be less committed to the job: whites had lower commitment when their teams were highly racially/ethnically dissimilar to them, whereas Latino and African-Americans had lower commitment when their teams were highly racially/ethnically similar to them (Riordan & Shore, 1997). The positive effect of racial/ethnic similarity on commitment and organizational attachment apparently holds only for white employees; racial/ethnic minorities fail to show such effects (Tsui et al., 1992). Likewise, white teachers in white-dominant schools reported higher job satisfaction, but African-American teachers showed no association between racial composition and job satisfaction (Mueller, Finley, Iverson, & Price, 1999).

Racial/ethnic similarity and working conditions

The literature has provided several starting points to explain the asymmetric reactions. First, compared with white employees, racial/ethnic minority employees typically work in lower-status jobs that have poorer physical and psychosocial working conditions (Murray, 2003). Thus, when white and racial/ethnic minority employees are compared across jobs, it remains unclear whether racial/ethnic groups show differences because of varying levels of racial/ethnic similarity, different working conditions, or both. Among white employees, low racial/ethnic similarity was associated with low job satisfaction, but the association disappeared after working conditions were accounted for (Maume & Sebastian, 2007). The authors concluded that white employees' lower job satisfaction was not a reaction to their decreasing racial/ethnic similarity but rather a reaction to unfavorable working conditions they share with racial/ethnic minorities. Likewise, the higher job satisfaction for white teachers in white-dominant schools vanished after working conditions and co-worker support were controlled for (Mueller et al., 1999).

Because those studies focused on white employees, we do not know whether the results apply to racial/ethnic minorities. A study of African-Americans and Latinos found an inverse J-shaped association between racial/ethnic similarity and job satisfaction (Enchautegui-de-Jesús, Hughes, Johnston, & Oh, 2006). Similar to the Maume and Sebastian study, the authors controlled for work hours, job control, and job demands. Latino and African-American employees who had no or all colleagues of the same race/ethnicity showed the lowest job satisfaction. The authors interpreted racial/ethnic similarity as a marker of working conditions not captured by the measures they used in the analysis. Those two studies suggested that the association between job satisfaction and racial/ethnic similarity may actually be the association between job satisfaction and working conditions, but neither study included both whites and racial/ethnic minorities. Investigating both racial/ethnic majority and minority groups within a single occupation as well as controlling for job characteristics will provide a clearer understanding of the relationship between racial/ethnic similarity and job satisfaction.

Status construction theory and occupational prestige

The status construction theory suggests an additional perspective that helps us understand asymmetric reactions to racial/ethnic similarity. Because different racial/ethnic groups have different status in the society, racial/ethnic concentration in certain jobs intertwines with occupational prestige and the status of the job holder (Kmec, 2003; Xu & Leffler, 1992). Occupational prestige is a collective, subjective consensus on the social status of a particular job (Xu & Leffler, 1992). In a racially homogeneous society, the social status of a job may be determined by the job's earning potential and educational requirement (MacKinnon & Langford, 1994) as well as the job's value to the society (Goyder, 2005). As society becomes more diverse, racial/ethnic minority concentration on the job becomes another marker of the job's status: The higher the minority concentration on the job, the lower is the status of the job (Kmec, 2003; Xu & Leffler, 1992).

In the United States, whites have historically been both the numerical majority and high-status racial group. Although they still have high status based on race, their numerical majority is shrinking, especially in blue-collar workplaces. In 2011, 42% of U.S. warehouse jobs were held by non-whites (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012). The growing proportion of racial/ethnic minority employees signals that these are low-status jobs. Occupational status has been associated with high self-esteem (Faunce, 1989), which is in turn associated with job satisfaction (Judge & Bono, 2001). Therefore, white employees whose colleagues are mainly racial/ethnic minorities would feel less satisfied with their jobs than would those who hold similar jobs in mainly white workplaces. For racial/ethnic minorities, in contrast, a sizable presence of white colleagues signals the job's higher status. Even though they belong to a low-status group based on race/ethnicity, their social status may seem improved if they have many white co-workers.

In sum, the status construction theory posits that Latinos and African-Americans, members of lower-status groups, are likely to favor working with whites, members of the higher-status group. Furthermore, the job's prestige will be perceived to be lower if the workplace has many racial/ethnic minorities. Therefore, after working conditions and social support are controlled for, both white and racial/ethnic minority workers will be more satisfied in white-dominant workplaces.

Hypothesis 1.Racial/ethnic similarity is associated with job satisfaction differently for whites and racial/ethnic minorities. For white workers, higher racial/ethnic similarity is associated with higher job satisfaction; for racial/ethnic minorities, higher racial/ethnic similarity is associated with lower job satisfaction.

Racial/ethnic similarity and health

Lumbar back health among warehouse workers

Job satisfaction is an important organizational outcome commonly linked to productivity and performance (Judge, Thorensen, Bono, & Patton, 2001), but employee health also has strong organizational importance as well because it is a major predictor of absenteeism and rising costs of medical treatment and insurance (Leigh, 2011). Especially in blue-collar workplaces, occupational injuries and illnesses carry higher risk than in other types of workplaces (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011). In this study of warehouse workers, we focus on their most common health problem, lumbar back disorders.

Back disorders are one of the most prevalent and costly occupational health problems in the United States, particularly among warehouse workers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011). Biomechanical risk factors such as heavy lifting, bending, and twisting have been extensively investigated. In addition, job characteristics other than physical demands, such as job control and social support, have also been associated with the onset of and speed of recovery from lumbar back disorders (Davis & Heaney, 2000; National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2001). In the latter line of research, there is burgeoning evidence that interpersonally stressful situations in the workplace increase the loading on the spine through biomechanical changes in trunk kinematics, exerted force, and muscle activity (Marras, Davis, Heaney, Maronitis, & Allread, 2000). That is, when stressed and nonstressed workers lift the same weight, the stressed worker is likely to experience greater compression force on the spine, which increases the risk for lumbar back injury (Marras et al., 2000). These stress-induced changes in the back muscle functioning may link racial/ethnic similarity to lumbar back health among warehouse workers because workplace racial/ethnic composition provides a social context in which the stress process occurs.

Racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health: status contamination

Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) alone is inadequate for explaining asymmetric responses to racial/ethnic similarity among different racial/ethnic groups (Chatman & O'Reilly, 2004). Combining social identity theory with a status-based construct—status contamination (Blalock, 1957; Reskin et al., 1999)—suggests a more complex relationship between racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health across different groups. As the presence of racial/ethnic minority groups grows, white employees may feel a higher risk of status contamination. That is, even though white employees have a high race-based status, their occupation-based status drops if they share the same job with many members of low-status groups (racial/ethnic minorities). Proximity to racial/ethnic minorities contaminates the higher status of being white. White employees, especially warehouse workers who typically have limited education, may be unable to leave a job easily. Thus, they must endure the threat of status contamination.

According to the social identity theory, once categorization occurs, people perceive members of their own social category as superior to others. As a result, they stereotype, distance, and disparage members of other categories (Tajfel, 1982). High-status group members who face the risks of status contamination may try to distinguish themselves clearly by intensifying their in-group favoritism as well as out-group disparagement and undermining (Ellemers, Spears, & Doosje, 2002). In a workplace with a large proportion of racial/ethnic minorities, whites would feel a greater threat of status contamination and be prompted to disparage racial/ethnic minority colleagues. In turn, this disparagement would lead to stressful situations in the workplace for racial/ethnic minorities. Thus, stress-induced spinal load may be increased for minorities who have high racial/ethnic similarity in the workplace (Marras et al., 2000). In other words, even though low-status group members may experience more positive social interactions with in-group members as they have higher racial/ethnic similarity, the benefit of having higher racial/ethnic similarity may be counteracted by negative social interactions with the high-status group members.

In contrast, a large proportion of whites in the workplace does not cause status contamination or loss of social status for racial/ethnic minorities. As the status construction theory suggests, racial/ethnic minorities in a white-dominant society may even prefer being associated with whites (Chattopadhyay et al., 2004; Fiske, 2002). White employees in a white-majority workplace would enjoy better social integration within their large in-group without receiving strong out-group disparagement from minority groups to counteract the benefit. Therefore, for white employees, a high racial/ethnic similarity creates less stressful working conditions, which are protective of their lumbar back health.

In summary, we argue that status contamination predicts stronger negative social interactions between whites and racial/ethnic minorities as minority presence increases because whites perceive status threat. For racial/ethnic minorities, this process may counteract the positive social interactions with in-group members as their racial/ethnic similarity increases, and as a result, positive effects of similarity attraction may diminish. When whites have a large presence, status contamination is not an issue for racial/ethnic minorities, and thus, disparagement against whites does not increase. Thus, we hypothesize the following.

Hypothesis 2.The association between racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health is moderated by race/ethnicity so that the positive association between racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health is significantly stronger for white employees than for racial/ethnic minority employees.

Racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health: social support and value threat

The social identity theory suggests that individuals receive more social support when their workplace includes more similar others (Tajfel, 1982). In a warehouse setting, employees surrounded by many colleagues of the same race/ethnicity may receive more help in handling heavy materials and, consequently, may have lower risk of lumbar back injuries. In addition, communication may be better in racially/ethnically homogeneous groups (cf. van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004), which could prevent accidents and maintain workplace safety in general (DeJoy, Schaffer, Wilson, Vandenberg, & Butts, 2004) and thus reduce the risk of back injuries. In addition to tangible supports, social identity theory suggests that racial/ethnic similarity is associated with emotional support and social integration (Guillaume, Brodbeck, & Ricetta, 2011). Warehouse employees who have low racial/ethnic similarity would have fewer sources of emotional support and would feel the stress of social isolation (Steptoe, Owen, Kunz-Ebrecht, & Brydon, 2004). Social identity theory clearly suggests higher levels of social support for all racial/ethnic groups as their racial/ethnic similarity increases.

Yet incorporating status construction theory indicates additional mechanisms for racial/ethnic minorities' social support exchange. Duguid, Lozd, & Tolbert (2012) argue that low-status racial/ethnic minorities strive to be valued by their high-status (white) co-workers. Concerned that their value may be overlooked because of their race/ethnicity (i.e., “value threat,” Duguid et al., 2012), minority employees may not engage in in-group favoritism and sharing of social resources with their minority colleagues. That is, the combined effect of being a racial/ethnic minority and belonging to a low-status group may limit their willingness to provide social support to their racial/ethnic peers if doing so threatens their status as valued members in a racially/ethnically mixed work unit.

In sum, social identity theory and similarity attraction paradigm suggest social support as a mediator: High racial/ethnic similarity will foster social support, which, in turn, positively affects lumbar back health. This process is likely to hold for all racial/ethnic groups. However, the value threat approach indicates that for racial/ethnic minority employees, the mediating effect of social support may be weaker. We therefore hypothesize the following moderated mediation effects of social support.

Hypothesis 3.The association between racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health is mediated by social support for all racial/ethnic groups. However, this mediation effect is significantly stronger for white workers than for racial/ethnic minorities.

Method

Participants and procedure

The data for this study come from a larger project on lumbar back health among employees handling heavy materials in nine U.S. furniture distribution centers (hereafter workplaces). Altogether, 471 warehouse workers completed the survey (response rate = 88%). Study participants included 254 whites, 105 African-Americans, 65 Latinos, and 47 workers of different or unknown ethnic backgrounds. In each workplace, workers performed a variety of jobs such as assembling furniture, receiving and stocking furniture pieces, keeping inventories, and driving delivery trucks. They mostly worked alone on their tasks but could ask their colleagues for help if needed. We grouped workers according to their job titles. This procedure resulted in 68 jobs nested within the nine workplaces. The number of workers in each job ranged from 2 to 23. Workers in jobs not shared by others could not be assigned to a job group and thus were excluded from the sample (n = 50). We also excluded workers with supervisory responsibilities and those in sales jobs (n = 26). Of the remaining sample, workers with a race/ethnicity other than white, African-American, or Latino as well as those who did not specify their race were excluded (n = 34). This procedure left a final sample of 361 warehouse workers. Table 1 shows the sample characteristics.

| Variables | White (n = 204) | African-American (n = 94) | Latino (n = 63) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%)/M (SD) | N (%)/M (SD) | N (%)/M (SD) | χ2/ANOVA | |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 189 (93%) | 91 (97%) | 60 (95%) | χ2(2, N = 361) = 2.19; p = .34 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 19 (9%) | 9 (10%) | 26 (41%) | χ2(6, N = 358) = 50.73; p < .001 |

| High school degree | 93 (46%) | 51 (54%) | 28 (46%) | |

| Some college | 68 (34%) | 26 (29%) | 7 (11%) | |

| College degree | 23 (11%) | 7 (7%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 97 (48%) | 23 (25%) | 8 (13%) | χ2(2, N = 360) = 31.73; p < .001 |

| Age | 35.89 (12.40) | 35.80 (10.16) | 33.17 (8.47) | F(2, 358) = 1.49; p = .23 |

| BMI | 25.80 (4.98) | 27.12 (4.83) | 27.66 (4.37) | F(2, 342) = 4.31; p = .01 |

| Company tenure (months) | 53.04 (54.48) | 58.19 (57.17) | 25.34 (20.17) | F(2, 352) = 8.51; p < .001 |

| Hours worked per week | 42.94 (6.93) | 42.12 (6.75) | 42.31 (5.94) | F(2, 351) = 0.55; p = .58 |

- ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMI, body mass index.

Almost all participants were men. Latino workers were less educated than African-American and white workers and on average had worked for the company for a shorter time. Thus, education and company tenure were controlled for in all analyses. White workers had a lower mean for the body mass index (BMI) and were more likely to be smokers than racial/ethnic minority workers. As BMI and smoking have been shown to affect lumbar back health (Shiri, Karppinen, Leino-Arjas, Solovieva, & Viikari-Juntura, 2010), they were controlled for in all analyses with lumbar back health as the outcome variable.

The study was approved by the Ohio State University's Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent. In small groups, workers were released from their work responsibilities to complete data collection activities. Self-administered questionnaires were available in English and Spanish. Of the 63 Latino workers, 53 completed the survey in Spanish. Because of low literacy, workers were given the option of having the questionnaire read to them.

Measures

Race/ethnicity

Two dummy variables were created for race/ethnicity: African-American (1 = African-American and 0 = others) and Latino (1 = Latino and 0 = others). Whites were used as the reference category.

Racial/ethnic similarity

Various measures of demographic similarity have been developed (Riordan & Wayne, 2008). Some measures have reflected perceived demographic similarity by asking respondents to report the extent to which they work with employees of the same ethnicity and/or race as themselves (e.g., Avery, Lerman, & Volpone, 2010; Enchautegui-de-Jesús et al., 2006). Other more objective measures have used organizational records to identify group composition and then calculated the similarity score for individual group members (Tsui et al., 1992). A common measure of relational demography is the d-score (Euclidean distance). It assumes that the effects of diversity are based on person-to-person social interaction but fails to capture the degree of social distance or the direction of differences (Joshi, Hui, & Roh, 2011; Riordan & Wayne, 2008). For example, the difference between a Latino worker and white colleagues is treated the same as a white worker's difference from African-American colleagues. Because of unequal social distance among racial/ethnic groups in the United States (McClain et al., 2006), it is inappropriate to use the d-score in a study with more than two racial/ethnic groups. In this study, we regard workplace racial composition as a context for each worker's social experience.

In organizational settings, groups have been defined most often as workgroups—employees who share a supervisor and work tasks. However, in our study sample, tasks were not necessarily assigned to clearly defined teams. Lawrence (2006) suggested using organizational reference groups. These groups are comprised of the employees whose name an individual might list if asked “Who populates your work world?” They may not work together on tasks but are aware of each other at work. Some studies have considered an employee's similarity to the workplace-wide workforce (e.g., Mueller et al., 1999; Zatzick, Elvira, & Cohen, 2003), and we adopt that approach to define workplace racial/ethnic similarity.

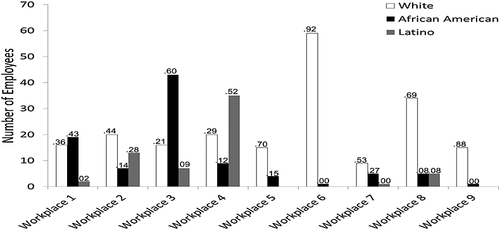

Following Williams and Meân (2004), we operationalized racial/ethnic similarity for each respondent by calculating the proportion of co-workers within the workplace who are of the same race/ethnicity as the respondent (i.e., proportional similarity). For example, if a workplace consists of 10 Latino, 20 African-American, and 70 whites, each Latino worker has a proportional similarity of 0.091 because nine other Latinos are among the 99 co-workers (9/99 = 0.091). For each of the African-Americans, 19 of 99 co-workers are of the same race; thus, proportional similarity is 0.192 for African-American and 0.697 for whites. Scores can range from 0 to 1, with higher numbers indicating higher levels of racial/ethnic similarity. The distribution of racial/ethnic similarity scores for each of the race/ethnicity groups is shown in Figure 1.

The lowest racial/ethnic similarity score for whites was 0.25 (Workplace 3), and the highest scores were 0.95 and 0.96 (Workplaces 6 and 9). For African-Americans, two workplaces (Workplaces 6 and 9) provided the lowest racial/ethnic similarity with 0. The highest racial/ethnic similarity for African-Americans was 0.59 (Workplace 3). The racial/ethnic similarity for Latinos ranged from 0 (Workplace 1) to 0.50 (Workplace 4). Although the groups' racial/ethnic similarity scores overlap considerably, Figure 1 shows that across the nine workplaces, Latino workers have the lowest and white workers have the highest proportion of co-workers of the same race/ethnicity. Note that because white workers account for almost 70% of the U.S. workforce (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012), even in a 45% white workplace, the white workers may experience “low” racial/ethnic similarity. In contrast, a Latino worker in a 45% Latino workplace might perceive quite high racial/ethnic similarity.

Work characteristics

To control for the effects of work characteristics, we used an objective measure for physical demands as well as self-report scales of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Generic Job Stress Questionnaire (GJSQ) for psychosocial work characteristics (Hurrell & McLaney, 1988).

Physical exertion

At the job level, a certified ergonomist measured five physical workload factors for each job: (1) frequency—the number of times per hour the job required physical exertion (e.g., lift, lower, push, pull, or carry an object); (2) duration—the proportion of the work day that demanded physical exertions; (3) force—the amount of weight lifted or force exerted; (4) horizontal distance—the distance from the spine to the hands during exertion; and (5) vertical location—the distance from the ground to the point of force exertion. Data from these five factors were consolidated and compared against threshold limit values (TLVs) determined by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH, 2001). TLVs are weight limits under which nearly all workers can perform physical exertions without developing lumbar back or shoulder disorders. For each job, the number of exertions above the TLVs per hour was calculated.

Perceived workload

Perceived workload was measured with three items asking about the amount of work and the extent to which respondents had to work very hard or fast (e.g., “How often does your job require you to work very fast?”). One item from the original four-item scale (“How often does your job leave you with little time to get things done?”) was deleted across all groups as it did not hold for the Latino subgroup in a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (results available on request). Cronbach's alpha for the three-item scale was .73.

Perceived job control

Five items asked about respondents' influence over job tasks in terms of the amount and type of work, flexibility in work schedules, and control over the process of accomplishing tasks (e.g., “How much influence do you have over the order in which you do tasks at work?”). Again, one item had to be deleted from the original six-item scale as it did not hold for the Latino subgroup (“To what extent can you do your work ahead and take a short rest break during work hours?”). Cronbach's alpha for the five-item-scale was .73.

Response options for both perceived workload and job control scales ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = a very great deal. Both scales were aggregated at the job level. See the Statistical Analysis section for interrater agreement among workers in the same jobs. CFAs at the job level (n = 68) support a good fit for perceived workload and job control as independent but correlated factors (χ2(19) = 21 235, p = .32; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.042 (CI [0.00, 0.12]); latent factor correlation: r = −.09).

Co-worker support

Co-worker support was measured with a four-item scale from the GJSQ (Hurrell & McLaney, 1988). Two items addressed emotional support (e.g., “How much are other people at work willing to listen to your personal problems?”), and two items addressed instrumental support (e.g., “How much can other people be relied on when things get tough at work?”). Cronbach's alpha was .77. Response options ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much. We conducted CFAs at the employee level (n = 361) with all self-report scales to ensure factorial invariance across racial/ethnic groups. CFAs with co-worker support, workload, and job control as independent but correlated factors revealed a good fit across racial/ethnic subgroups (χ2(153) = 177 332, p = .09; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.02 (CI [0.00, 0.03])).

Workplace size

Measures for demographic similarity have been criticized for not accounting for group or workplace size (Williams & Meân, 2004). For example, in large workplaces, a proportion of 30% Latino employees is more easily recognized than the same proportion of Latino employees in smaller workplaces because the actual number of Latino employees differs considerably (e.g., 30 Latinos in a workplace with 100 employees compared with three Latinos in a workplace with 10 employees). Also, having more similar others in larger workplaces is likely to increase the probability of social interactions with persons of the same race/ethnicity (Wegge, Roth, Neubach, & Schmidt, 2008). We therefore added workplace size (number of employees per workplace) as a control variable at the workplace level. The scores are based on the original sample of 471 workers and ranged from 22 for the smallest up to 85 for the largest workplace.

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured with a four-item scale adapted from the GJSQ (Hurrell & McLaney, 1988). The items focused on global job satisfaction (Item 1: “take the same job if you had the choice to start over again”; Item 2: “take the same job if you were free to go into any job you wanted”; Item 3: “recommend the job to friends who are interested in working in your field”; Item 4: “All in all, how satisfied are you with your job?”). Response options ranged from 1 to 3, with higher numbers indicating higher job satisfaction. Cronbach's alpha was .77. CFAs at the employee level support a good fit across the three racial/ethnic subgroups (χ2(6) = 11 515, p = .07; CFI = 0.99; NFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.05 (CI [0.00, 0.08])).

Lumbar back health

The lumbar motion monitor, a triaxial electrogoniometer, was used to quantify dynamic trunk motion performance (Marras, Fathallah, Miller, Davis, & Mirka, 1992). The lumbar motion monitor was placed on each worker with a belt and shoulder harness. The participant was then asked to perform a set of standardized exertion tasks: flexing and extending the trunk, twisting clockwise and counterclockwise, and bending side to side (Marras et al., 2000). From the range of motion, velocity, and acceleration data collected, an age-adjusted summary variable was calculated to indicate the worker's lumbar back health. This variable has a continuous score from 0.0 to 1.0, with higher scores indicating healthier functioning of the back muscles. This measure has been shown to be consistent with clinical history and has been used to measure recovery from lumbar back disorders (Cherniack et al., 2001; Ferguson, Marras, & Gupta, 2000).

Sociodemographic control variables

We controlled for company tenure, education, BMI, and smoking because they influence the outcomes of interest and differ across racial/ethnic groups as shown in Table 1 (Gonzalez & Denisi, 2009; Shiri et al., 2010). Company tenure was measured in months with one item: “How long have you worked for this company?” Participants reported their highest level of education: less than high school diploma, high school diploma, some college or vocational training, and college degree or higher. BMI was calculated with self-reported height and weight. To assess current smoking status, we asked, “Do you currently smoke?” Participants answered yes (1) or no (0).

Statistical analyses

Missing data

As described earlier, workers with unique jobs and no race/ethnicity information were excluded from the analysis, leaving a sample of n = 361. Some study variables had missing data (missing rate = 0.3–4.4%). To account for missing data, we conducted multiple imputation (PROC MI on sas v.9.2) to create 10 complete data sets and analyzed them separately in HLM. Coefficient estimates from the 10 imputed data sets were combined according to Rubin's (1987) procedure. Lumbar back health, one of the dependent variables, had no missing data. Four participants provided no job satisfaction data and were excluded from the job satisfaction analysis because we did not impute dependent variables (von Hippel, 2007).

Interrater agreement

In our data, employees (Level 1) are nested within jobs (Level 2), and we have three variables at Level 2. Whereas physical exertion was objectively measured at the job level, job control and perceived workload were measured at the individual level. Within the context of multilevel modeling, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC(1)) is generally used to indicate the extent to which individual worker ratings are attributable to group membership (de Jonge, Mulder, & Nijhuis, 1999). In our data, workers demonstrated considerable agreement in the evaluation of perceived workload within each job. For perceived job demands, the ICC(1) was 0.14 (F(68, 311) = 1.85, p < .001), which indicates a medium effect (see Murphy & Myors, 1998, for classification of effect sizes) and suggests that the workers' ratings on perceived workload was indeed influenced by the job. For job control, the ICC(1) was 0.07 (F(68, 308) = 1.39, p < .05), which indicates a small effect. The rwg(j), a measure for within-group agreement that compares the observed group variance among raters with an expected random variance (James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1984; Lüdtke & Robitzsch, 2009), was at an adequate level for both scales (the mean rwg(j) = .86 for quantitative workload and .71 for job control). All coefficients indicated that it is acceptable to aggregate perceived workload and job control at the job level.

Multilevel analyses

We tested two three-level hierarchical linear models using HLM 6.08 (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002): one with job satisfaction and the other with lumbar back health as the outcome variable. Our predictor variables at Level 1 (i.e., the employee level) were two dummy variables coding whether the individual's race/ethnicity was African-American or Latino (with whites as the reference group), racial/ethnic similarity, two interaction terms of dummy-coded race/ethnicity by racial/ethnic similarity, and sociodemographic control variables. Predictor variables at Level 2 (the job level) were perceived workload and job control job (as aggregated self-report measures of psychosocial work characteristics), and the physical exertion measure for each job (as an objective measure of physical demands). We included these variables at Level 2 rather than at Level 1 because they measure characteristics of the job rather than characteristics of the individual. Finally, the sole predictor variable at Level 3 (the workplace level) was workplace size.

All continuous variables were grand-mean centered to allow us to interpret the Level 2 and 3 intercepts. Because of a limited number of workplaces at Level 3, we estimated fixed effects at Levels 2 and 3. As goodness-of-fit indicators, deviance, Akaike information criterion, and pseudo-R2s were reported using the calculations recommended by Luke (2004).

Moderated mediation

To test whether co-worker support mediated the effect of racial/ethnic similarity on lumbar back health for white, African-American, and Latino workers, we ran moderated mediation analyses in Mplus 5.2 (1998–2008) (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). We followed Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes's (2007) Model 2, which tests the moderation effect of race/ethnicity on the path from racial/ethnic similarity to co-worker support.

Results

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelation for all study variables at the employee level, stratified by racial/ethnic groups. For job satisfaction, we found significant correlations with psychosocial work characteristics in the expected directions only among whites. Physical exertions were negatively associated with job satisfaction among whites and African-American workers. Co-worker support was positively associated with job satisfaction among whites and Latinos. For lumbar back health, we found mostly null correlations with all psychosocial work characteristics across groups. Co-worker support revealed a significant positive association with lumbar back health for African-American and Latinos workers. We calculated analyses of variance to compare mean differences in all study variables among racial/ethnic groups. Interestingly, white workers consistently differed from African-American and Latino workers by showing higher perceived workload, lower physical exertions, higher racial/ethnic similarity, and poorer lumbar back health. Latino workers showed higher job satisfaction as compared with white and African-American workers.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whitea | — | 53.04 (54.48) | — | 25.80 (4.98) | 3.69 (0.77) | 3.24 (0.85) | 51.50 (24.77) | 2.92 (0.65) | 0.66 (0.26) | 1.56 (0.30) | 0.52 (0.29) |

| African-American | — | 58.19 (57.17) | — | 27.12 (4.83) | 3.40 (0.86) | 3.22 (0.98) | 61.26 (24.78) | 2.99 (0.72) | 0.41 (0.20) | 1.54 (0.28) | 0.68 (0.22) |

| Latino | — | 25.24 (20.17) | — | 27.66 (4.37) | 3.40 (0.90) | 3.40 (0.91) | 59.05 (21.47) | 3.02 (0.70) | 0.38 (0.18) | 1.74 (0.24) | 0.60 (0.25) |

| 1. Educationb | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Company tenureb | .04/−.11/−.09 | — | |||||||||

| 3. Smokingc | −.13/.19/−.08 | −.10/−.31/−.16 | — | ||||||||

| 4. BMIb | .14/.06/.45 | −.12/−.37/−.02 | .16/.30/−.16 | — | |||||||

| 5. Perceived workloadc | −.13/−.10/.07 | −.14/−.11/.15 | .02/.13/.02 | .09/.17/−.16 | — | ||||||

| 6. Perceived job controlc | −.11/.03/.19 | .19/−.02/.11 | −.01/.02/.02 | .08/.02/.02 | −.11/.06/.37 | — | |||||

| 7. Physical exertionc, d | −.05/−.13/−.19 | −.35/−.42/−.17 | −.03/.13/−.10 | .06/.23/−.14 | .15/.01./17 | −.11/−.17/.15 | — | ||||

| 8. Co-worker supportb | .15/.18/−.05 | .21/−.05/−.00 | −.14/.13/−.12 | .05/.06/−.02 | −.06/.01/−.07 | .05/.21/.04 | −.05/.20/.02 | — | |||

| 9. Ethnic/racial similarityb | −.05/.16/−.14 | −.14/.20/−.05 | .04/.07/−.20 | −.12/−.02/−.14 | .09/−.07/−.26 | −.13/−.18/−.32 | −.12/.12/.23 | −.09/.21/.04 | — | ||

| 10. Job satisfactionb | −.06/−.13/−.15 | .18/.35/.02 | −.02/−.12/.16 | −.06/−.21/.16 | −.31/−.09/−.20 | .28/.13/−.08 | −.21/−.25/.10 | .17/.04/.26 | .04/−.02/−.16 | — | |

| 11. Lumbar back healthb | .14/−.05/.14 | −.21/−.01/.09 | −.01/.20/−.13 | .27/.27/.14 | −.01/−.07/.06 | .07/.01/.03 | .02/.05/−.17 | .12/.22/.28 | −.19/.19/.18 | −.04/−.02/.03 | — |

- Bold emphases indicate significant mean differences/correlations at p < .05; bold italics emphases indicate significant mean differences/correlations at p < .01.

- a Mean differences are bolded for the racial/ethnic group that statistically differs from the other two groups; standard deviations are in parentheses. Correlations are reported by race/ethnicity as follows: white/African-American/Latino.

- b Variables used at the employee level in the HLM model.

- c Variables used at the job level in the HLM model;

- d Physical exertion scores were calculated at the job level (n = 68) but then assigned to individual workers.

Multilevel analyses for job satisfaction

The results for the multilevel analyses are presented in Table 3. At the employee level, racial/ethnic similarity, being Latino, and the interaction of the two were all significantly associated with job satisfaction.

| Parameter | Job satisfaction | Lumbar back health | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | B | SE | t | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.54 | 0.02 | 69.72*** | 0.55 | 0.03 | 21.07*** |

| Level 1 (employee) | ||||||

| Education | −0.04 | 0.02 | −2.26* | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.63 |

| Company tenure | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3.30** | −0.01 | 0.00 | −3.17** |

| Smoking | — | — | — | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.51 |

| Body mass index | — | — | — | 0.01 | 0.00 | 4.03*** |

| African-Americana | 0.13 | 0.09 | 1.48 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.20 |

| Latinoa | 0.39 | 0.10 | 4.02*** | −0.17 | 0.09 | −1.85† |

| Racial/ethnic similarity | 0.16 | 0.08 | 2.09* | −0.13 | 0.07 | −1.84† |

| African-American by racial/ethnic similarity | −0.30 | 0.17 | −1.72† | 0.30 | 0.15 | 1.96* |

| Latino by racial/ethnic similarity | −0.47 | 0.21 | −2.27* | 0.36 | 0.20 | 1.79† |

| Co-worker support | 0.06 | 0.02 | 2.88** | 0.06 | 0.02 | 2.90** |

| Level 2 (job) | ||||||

| Perceived workload | –0.05 | 0.03 | −1.48 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.58 |

| Perceived job control | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.80† | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.85 |

| Physical exertions | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.37 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.67† |

| Level 3 (workplace) | ||||||

| Workplace size | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.04 |

| Random effects | ||||||

| Level 1 intercept variance (SE) | 0.07 (0.27) | 0.06 (0.24) | ||||

| Level 2 intercept variance (SE) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.04) | ||||

| Level 3 intercept variance (SE) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | ||||

| Pseudo-R2 | .16 | .20 | ||||

| Fit statisticsb | ||||||

| Deviance | 123.11 (67.18) | 59.78 (0.89) | ||||

| Akaike information criterion | 147.11 (91.18) | 87.78 (28.89) | ||||

- a Whites as reference group.

- b Fit statistics are for the null model and full model (in parentheses).

- † p < .10;

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < 0.001.

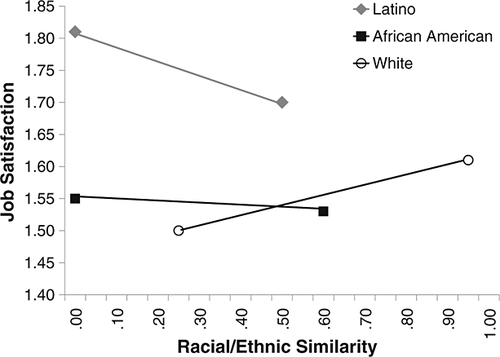

Figure 2 plots these associations, showing that Latino workers were generally more satisfied with their jobs than white workers but that those with higher racial/ethnic similarity had lower job satisfaction. For white workers, the higher the racial/ethnic similarity, the higher is their job satisfaction. The difference between the slopes for white and Latino workers was statistically significant (Β = −0.47, p = .024). The difference between the slopes for white and African-American workers was marginally significant (Β = −0.30, p = .086). For African-American workers, racial/ethnic similarity was not associated with job satisfaction. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported.

Table 3 further shows that at the individual level, company tenure, education, and co-worker support were positively associated with job satisfaction. At the job level, only job control was marginally associated with job satisfaction. We found no effect of workplace size at Level 3. Across all three levels, the predictors accounted for 16% of the variance in job satisfaction. The largest portion of variance was explained at the employee level (pseudo-R2 at Level 1 = .13).

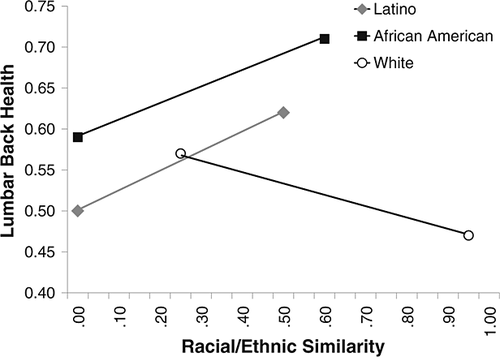

Multilevel analyses for lumbar back health

The results for lumbar back health appear in the right column of Table 3. At the employee level, company tenure, BMI, and co-worker support were significant predictors for lumbar back health. Having worked longer for the company and having a higher BMI both negatively affected lumbar back health. Regarding our hypotheses, we found a significant interaction term for being African-American by racial/ethnic similarity (Β = 0.30, p = .050). We also found a marginal effect for the interaction of being Latino by racial/ethnic similarity (Β = 0.36, p = .074). Figure 3 plots these interactions, showing that among Latino and African-American workers, higher racial/ethnic similarity was associated with better lumbar back health whereas for white workers, higher racial/ethnic similarity was associated with poorer lumbar back health. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

Table 3 also shows that at the job level, we found no significant associations of psychosocial work characteristics with lumbar back health. Physical exertions were marginally negatively associated with lumbar back health (B = −01.67, p = .100). Again, we found no effects of workplace size at Level 3. Across all three levels, the predictors accounted for 20% of the variance in lumbar back health. The largest portion of variance was explained at the employee level (pseudo-R2 at Level 1 = .197).

Mediation effect of co-worker support

As shown in Table 3, co-worker support has a significant direct effect on lumbar back health (B = 0.06, p = .004). We conducted moderated mediation analysis (Preacher et al., 2007) to test the mediation effect of co-worker support in the relationship between racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health separately for racial/ethnic groups. Following Model 2 of Preacher et al. (2007), the moderation effect of race/ethnicity was tested on the path of racial/ethnic similarity on co-worker support (Path a′). For white workers, the mediation effect of co-worker support was not significant (Β = −0.01, SE = 0.01, p = .40). Indirect effects for African-Americans and Latinos were estimated by respecifying the path model using African-Americans and Latinos, respectively, as the reference category for dummy variables. The mediation effect was not significant for either African-American (Β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = .22) or Latino workers (Β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = .39). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was not supported for all racial/ethnic groups.

Discussion

The aim of this study is to investigate different processes through which racial/ethnic similarity affects job satisfaction and lumbar back health among workers of three racial/ethnic groups. As asymmetry hypothesis predicts, racial/ethnic similarity differentially affects worker job satisfaction and objectively measured lumbar back health: Racial/ethnic similarity is positively associated with job satisfaction among whites, but the association is negative for Latinos. The associations are in opposite directions for lumbar back health. After working conditions and social support are controlled for, racial/ethnic similarity is negatively associated with lumbar back health among whites and positively among Latino and African-Americans. Because the two outcomes are quite different in nature, we discuss the results for job satisfaction and lumbar back health separately in the following sections.

Racial/ethnic similarity and job satisfaction

Our asymmetry hypothesis stated that racial/ethnic similarity and job satisfaction would be positively associated for whites and negatively associated for racial/ethnic minorities. The data supported the hypothesis for whites and Latinos but not for African-Americans. During data collection, we did not ascertain participants' immigration status; however, most of the Latinos preferred Spanish as the data collection language, which indicates that most of them may have been recent immigrants (Taylor, Lopez, Martinez, & Velasco, 2012; Vega et al., 1998). Our findings suggest that racial/ethnic composition in the workplace may have different meanings not only for racial/ethnic majority and minorities but also for immigrants (i.e., Latinos in our study) and racial/ethnic minorities native to the country (i.e., African-Americans in our study).

According to the status construction theory, a higher proportion of whites in the workplace signals higher occupational prestige (Kmec, 2003), which could be experienced by immigrants as a marker of upward social mobility. Immigrants and racial/ethnic minorities native to the country may have quite different expectations and perceptions about social mobility (Cole & Omari, 2003; Vallejo, 2012; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Upward social mobility is particularly important for immigrants. For many, seeking economic opportunity is their major reason for migrating (Gong, Xu, Fujishiro, & Takeuchi, 2011; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Because Latino immigrants commonly expect that migration to the United States will provide better jobs, working in a workplace with a high proportion of American employees, especially whites (McClain et al., 2006; Portes & Zhou, 1993), may enhance perceived social standing whereas working in a Latino-dominant workplace may not. Immigrants whose social standing declined after migration (e.g., a physician in the home country now drives a taxi in an adopted country) typically experience low job satisfaction (Dean & Wilson, 2010; Kats, 1983). If the reverse is true, those immigrants who perceive their social standing to be increased would have higher job satisfaction. Thus, our finding for Latinos and job satisfaction may reflect that low racial/ethnic similarity for Latinos implies increased social standing for them, which in turn increases their job satisfaction. We are unaware of any study on immigrants' perceived social standing based on workplace racial composition, but lower neighborhood racial/ethnic similarity for Latinos has been associated with higher subjective social standing (Reitzel et al., 2010).

For African-Americans, upward mobility in the white-dominant society may be more complicated than it is for immigrants. Reviewing the history of class divisions within the African-American community, Cole and Omari (2003) pointed out African-Americans' deep-rooted “consciousness of their race as a socially and economically oppressed group” (p. 790) even after some of them have achieved middle-class status. Merely working with many white colleagues, especially in a low-paid manual-labor occupation, may not give African-American workers a sense of upward mobility. Moreover, African-Americans who have frequent contacts with whites become more aware of systemic disadvantages relative to whites (Hughes & Demo, 1989; Hwang, Fitzpatrick, & Helms, 1998). In our study, the African-American participants with the lowest racial/ethnic similarity worked in strongly white-dominant workplaces (about 95% whites) rather than in racially/ethnically somewhat balanced workplaces. Thus, those who work mainly with whites may have a stronger sense of racial disadvantages, which may have attenuated the benefits of working with a large high-status group. Future studies should investigate directly the role of perceived occupational prestige and racial advantage/disadvantage in relation to the workplace racial composition.

What is clear from our results is that asymmetric reactions to racial/ethnic similarity exist not only between high-status and low-status groups but also among low-status groups. Even though they are both low-status minority groups, Latino immigrants and African-American workers react differently to racial/ethnic similarity. Research on racial/ethnic similarity must carefully consider different histories and relationships with the dominant group.

Racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health

Our hypotheses for racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health were based on different processes from those hypothesized for job satisfaction. As an attitudinal outcome, job satisfaction reflects the person's perceptions of the job; however, a health outcome reflects how the job is performed, whether in health-enhancing or health-damaging ways. Although job perceptions clearly influence employee health (Faragher, Cass, & Cooper, 2005), we examine a direct association between racial/ethnic similarity and health by using lumbar back health as an objective measure. As the first investigation using objective health measures, our analysis provides important evidence for the link between racial/ethnic similarity and employee health.

Our results show that the associations for each of the racial/ethnic groups are in the opposite direction of the associations with job satisfaction. In addition, different racial/ethnic groups have different associations between racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health although the associations were in different directions from what we hypothesized. Among Latino and African-American workers, higher racial/ethnic similarity is associated with better lumbar back health whereas for white workers higher racial/ethnic similarity is associated with poorer lumbar back health.

Same job titles, different tasks: differential distribution of work demands

The only other published study to examine workplace racial/ethnic similarity and health reported that a moderate level of racial/ethnic similarity in the workplace was associated with the lowest level of psychosomatic complaints among Latino and African-American employees (Enchautegui-de-Jesús et al., 2006). The authors argued that poor working conditions are responsible for poorer health for employees in workplaces with a large proportion of non-white employees. Our study was conducted with white, Latino, and African-American employees who worked in the same workplaces, performing similar jobs within a single occupation. In addition, our multivariate models controlled for an objective measure of physical exertion and several psychosocial work characteristics at the job level. Thus, differences among worksites and jobs are unlikely to explain our findings.

However, the status construction theory helps us understand the lumbar back health results. Because African-Americans and Latinos have less access to resources, they have lower social status and are generally seen as less worthy members in society (Ridgeway, 1991) and in the workplace. In addition, if Latino and African-American workers have low racial/ethnic similarity, their presence is highly visible, and their performance is under scrutiny, as the literature on women in men's occupation has shown (Kanter, 1977). In response, racial/ethnic minority employees may try harder (e.g., volunteer for extra work and heavier tasks) to improve their value as workers. This high-effort coping not only causes greater physical demands on the spine but also activates the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis (Merritt, McCallum, & Fritsch, 2011), both of which may increase the risk for lumbar back injuries (Marras et al., 2000).

For white employees, contrary to our hypothesis, higher racial/ethnic similarity was associated with poorer lumbar back health. Some evidence indicates that Spanish-speaking employees and employees with low educational attainment perform more physically demanding tasks than others in the same occupation (Autor & Handel, 2009). Perhaps even within the same jobs, Latino employees perform tasks that negatively affect their lumbar back health more often than do white employees. In white-dominant workplaces, white employees may need to perform these undesirable tasks themselves. Unfortunately, we could not fully explore this possibility because the race/ethnicity of the workers we observed for measuring the physical demands of jobs was not documented. Future studies would benefit from measuring job tasks and characteristics separately for employees in different racial/ethnic groups.

The role of social support

Our data did not support our hypothesis that social support would mediate the association of racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health. The bivariate correlations (Table 2) already show that racial/ethnic similarity and co-worker support are not correlated among whites and Latinos. African-Americans do have a significant bivariate correlation between racial/ethnic similarity and co-worker support, but even for them, the mediation effect is not significant. This is not consistent with the theoretical and empirical literature on racial/ethnic similarity, which has consistently proposed associations with social support, social integration, and related constructs (see Guillaume et al., 2011 for a meta-analytic integration).

Although co-worker support is unlikely to be a function of racial/ethnic similarity in our sample, we find a moderate level of co-worker support across all three racial/ethnic groups and strong direct effects on job satisfaction and lumbar back health (Tables 2 and 3). This suggests that social support can be exchanged regardless of the level of racial/ethnic similarity. There are several possibilities that may explain our findings. First, social support may be exchanged across different racial/ethnic groups. In fact, some community studies have reported no association between racial/ethnic similarity in the neighborhood and social support (Hutchinson et al., 2009; Phan, Blumer, & Demaiter, 2009). Second, although having more similar others in the workplace increases the chance of working directly with co-ethnic co-workers, it is also possible that immediate colleagues may not be of the same race/ethnicity. This ambiguity is a drawback of using the workplace as the unit for defining ethnic/racial similarity rather than a smaller unit such as the work team. Unfortunately, we did not specify the source or type of social support, and thus, we cannot further examine the lack of association between racial/ethnic similarity and co-worker support.

Finally, workplace size could affect the relationship of racial/ethnic similarity and co-worker support. In a large workplace, a moderate proportion of similar others among racial/ethnic minorities provides numerically more possibilities for social interactions with co-ethnic co-workers than a small workplace with the same proportion of minorities. Therefore, effects of co-worker support may be stronger in larger workplaces. Thatcher and Patel (2011) showed in their meta-analysis that a homogeneous subgroup provides social support in the face of a problematic out-group. In a large workplace that provides more possibilities for social interactions, higher racial/ethnic similarity for minorities may buffer the detrimental effects of disparagement from the high-status group. The nine workplaces in this study did not allow us to test for cross-level interactions of workplace size, but future studies on racial/ethnic similarity should consider team or workplace size as a potential moderator.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

We believe this study is the first to assess the relationship between racial/ethnic similarity and employee health using an objective measuring device, the lumber motion monitor, for employee lumbar back health. We also use a computed rather than self-reported measure of racial/ethnic similarity. Computed measures of racial/ethnic similarity allow the possibility that racial/ethnic similarity can influence individuals regardless of how much they notice their differences (Riordan & Wayne, 2008). In using a proportional measure of racial/ethnic similarity, we extend previous studies on asymmetric effects of racial/ethnic similarity on job satisfaction that have typically applied the d-score as a measure for demographic similarity (e.g., Riordan & Shore, 1997; Tsui et al., 1992). Whereas the d-score assesses similarity between an individual's race/ethnicity and that of all others in a unit, our proportional similarity measure allows a clearer differentiation between racial/ethnic subgroups by providing a score representing the proportion of co-workers of the same race/ethnicity. This study also addresses factors that may influence employees' job satisfaction and lumbar back health at multiple levels of analysis. The respondents were all employed in the same occupation, which eliminates the confounding effect of different occupations found in the Enchautegui-de-Jesús et al. (2006) study. However, this also limits the generalizability of our findings; they may not be applicable to other occupations.

Besides limited generalizability, other limitations should be acknowledged. Only nine workplaces participated, which restricted statistical power to detect workplace-level effects and prohibited testing for cross-level interactions. Moreover, we also did not have the full range of racial/ethnic similarity scores for all racial/ethnic groups. For whites, scores ranged from 0.25 to almost 1.00; for minority groups, scores ranged from 0.00 to 0.59 for African-Americans and up to 0.50 for Latinos. Therefore, we could not investigate effects of very low racial/ethnic similarity for whites or very high racial/ethnic similarity for African-Americans or Latinos. A study representing the full range for racial/ethnic similarity would permit testing more precise comparisons across racial/ethnic groups as well as more complex associations such as curvilinear relationships. Yet it would be quite difficult to obtain the full range of racial/ethnic similarity for all racial/ethnic groups because in many organizations, the demographic composition of work units prohibits a balanced design.

Practical implications

Our findings allow first suggestions for practitioners who aim to design healthy workplaces. When we examine the slopes for racial/ethnic similarity and lumbar back health (Figure 3), all three groups seem to show better lumbar back health if their racial/ethnic similarity is between 0.30 and 0.70. That is, both white and minority employees in a somewhat balanced workplace appear to have better lumbar back health. Perhaps under such conditions, race/ethnicity is a less salient characteristic for defining in-groups: Boundaries between groups may be more permeable, and workers may share more resources and give more social support. Our data suggest that racially/ethnically balanced rather than segregated workplaces provide an environment most beneficial to employee health. Research should still investigate mechanisms causing these effects. However, management should be at least aware that in a racially/ethnically diverse workplace, various dynamics other than similarity attraction come into play. Clearly, we need research that explores additional processes that may influence relationships between racial/ethnic similarity and employee health.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (grant number: 5R01OH0391403). We thank JOB's associate editor, B. Baltes, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on drafts of this article.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Biographies

Annekatrin Hoppe is a work and organizational psychologist whose research focuses on occupational health and ethnic health disparities among blue-collar workers. She has focused on the development of research methodologies for surveying multiethnic worker populations and investigated psychosocial working conditions and health among immigrant workers in Western societies. More recently, she has focused on diversity, well-being, and health in culturally diverse teams and organizations.

Kaori Fujishiro is a social epidemiologist who investigates occupational health from a sociostructural perspective. Her recent work analyzes the relationship between work characteristics and subclinical cardiovascular disease using multiethnic samples. Dr. Fujishiro's research strives to disentangle the complex way in which occupation affects workers' health.

Catherine A. Heaney's research program focuses on psychosocial factors at work (occupational stress, social support at work, and organizational justice) that are associated with health and disease. Furthermore, she has specialized on biomechanical risk factors and musculoskeletal disorders. She also conducts intervention research to develop strategies for enhancing employee resiliency and reducing exposure to psychological and behavioral risk factors at work.