Quantitative analyses of the distal bipolar electrogram for focal premature ventricular contraction ablation

Abstract

Background

Accurate interpretation of the distal bipolar electrogram (bi-EGM) is essential for successful ablation of idiopathic focal PVC. Sharp, early, and fractionated bi-EGM is often considered to be near-field and targeted, but in an empiric fashion rather than by quantitative criteria.

Objectives

To quantify the distal bi-EGM with five parameters to elucidate quantitative criteria distinguishing near-field from far-field bi-EGM.

Methods

The distal bi-EGM was quantified and analyzed using: half time of activation (t½), slope factor (S, derived by fitting the Boltzmann equation), linear slope (dV/dt), time from onset of bi-EGM to surface ECG (Ts) and number of deflections (De#).

Results

Among 41 patients, 26 were ablated successfully and 15 unsuccessfully. t½ and S, defining the sharpness of the activation process, were significantly different between the two groups (3.2 ± 0.3 vs. 5.9 ± 0.6 ms, p < 0.001 and 0.8 ± 0.1 vs. 4.8 ± 2.0, p = 0.01). Ts was earlier in the successful group (35.6 ± 1.3 vs. 25.8 ± 1.6 ms, p < 0.01). dV/dt and De# were not statistically different (0.2 ± 0.04 vs. 0.1 ± 0.02 mV/ms, p = 0.06; and 2.7 ± 0.2 vs. 2.3 ± 0.3, p = 0.22). The 5 parameters showed indifference across anatomic locations. AUCs of ROC curve are >0.8 (t½ 0.85, S 0.85 and Ts 0.87).

Conclusion

t½, S and Ts are precise in quantifying the sharpness and earliness of distal bi-EGM; therefore, discriminating the near-field from far-field bi-EGM for guiding successful ablation.

1 INTRODUCTION

The activation and propagation of idiopathic focal premature ventricular contraction (PVC) are complex and non-linear. Accurate interpretation of the intracardiac electrogram (EGM) recordings, both bipolar (bi-EGM) and unipolar (uni-EGM), has been a focal point of research and clinical practice for nearly 60 years since the inception of intracardiac recording in the clinical electrophysiology lab.1-3 Multiple factors may influence the recordings, including the location and depth of PVC origin, resistive conduction, anisotropy of the surrounding tissue, and the recording techniques such as filtering, electrode spacing, and catheter orientation.1, 4, 5 Recent studies suggest that uni-EGM may have limited utility in guiding successful ablation of focal PVCs. Rather, bi-EGM may have a more advantageous role in this regard.6, 7

bi-EGM is recorded between more closely spaced extracellular electrodes, providing information of “local” electrical activities. Typical bi-EGM consists of multiple components in the case of focal PVCs, reflecting the initial activation beneath the recording electrodes and subsequent propagations centrifugally.1, 4 Often vaguely defined terms of near-field and far-field bi-EGM are used to determine the location of focal PVCs and therefore the site for ablation,1, 8, 9 a process mostly empirical and visual. The near-field bi-EGM is generally considered as being sharp, early, and more fractionated, therefore targeted for ablation, while the far-field bi-EGM is considered as being the opposite. However, no quantitative criteria have been established to distinguish the two for the purpose of successful ablation.

This retrospective study aims to (1) define a set of quantitative parameters to quantify the distal bi-EGM for its sharpness, earliness, and degree of fractionation; (2) determine the differences in these parameters between successful and unsuccessful ablations and therefore define the near-field and far-field bi-EGM for the purpose of successful ablation; and (3) establish the performance value of these parameters.

2 METHODS

2.1 Patient population

Seventy-four consecutive patients with PVCs who underwent catheter ablations at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center Los Angeles from 1/2021 to 12/2023 were queried. Of these, 41 were included in the study for having undergone ablations for idiopathic focal PVCs after excluding cases with scar-related or multi-focal PVCs. All patients were symptomatic from PVCs that were refractory to at least one antiarrhythmic, including calcium channel blocker, beta-blocker, and/or class Ic antiarrhythmic. Comprehensive clinical evaluations were performed in all patients, which included medical history, physical exam, mobile cardiac monitoring for PVC burden, 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs) for PVC morphology, and 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) to assess LVEF and rule out wall motion abnormalities. Cardiac MRI was done in 22 patients to rule out structural and infiltrative heart disease, and ischemic work-ups were done as needed. The average LVEF was 55.6% (Table 1). Electronic medical records (EMR) were used to categorize patient demographics, including sex and race identified based on self-identification, and identify medical comorbidities and variables for the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and data collection and analyses were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kaiser Permanente Southern California-Hawaii region and in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

| Successful N = 26 | Unsuccessful N = 15 | Combined N = 41 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (n ± SD) | 49.85 ± 15.05 | 54.53 ± 11.83 | 51.56 ± 13.99 | 0.30 |

| Sex | 0.62 | |||

| Men | 10 (38.46) | 7 (46.67) | 17 (41.46) | |

| Women | 16 (61.54) | 8 (53.33) | 24 (58.54) | |

| Race | 0.49 | |||

| White | 13 (50.00) | 5 (33.33) | 18 (43.90) | |

| Asian | 8 (30.77) | 4 (26.67) | 12 (29.27) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (15.38) | 4 (26.67) | 8 (19.51) | |

| Black | 1 (3.85) | 2 (13.33) | 3 (7.32) | |

| Hypertension | 8 (30.77) | 4 (26.67) | 12 (29.27) | 0.08 |

| Type II diabetes | 3 (11.54) | 2 (13.33) | 5 (12.20) | 0.87 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7 (26.92) | 5 (33.33) | 12 (29.27) | 0.67 |

| LVEF (n ± SD) | 56.31 ± 8.49 | 54.33 ± 10.50 | 55.59 ± 9.20 | 0.52 |

| PVC burden (n ± SD) | 20.17 ± 12.83 | 22.43 ± 14.43 | 21.05 ± 13.31 | 0.63 |

| Prior ablation | 1 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.44) | 0.44 |

2.2 Electrophysiology study and catheter ablation

All patients were prepared and draped in standard sterile fashion. Venous accesses were obtained via the right femoral vein, and the catheters were advanced to the coronary sinus, RV apex, and RV outflow track under the guidance of the fluoroscope and CARTO mapping system (Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, California). Access to the aortic cusp and the LV was achieved through either a retrograde aortic approach or a transseptal puncture performed under the guidance of fluoroscope, intracardiac echocardiography, and intracardiac pressure monitoring. The targeted activated clotting time was 300–400 s using heparin boluses or infusions. Mapping and ablation in all cases were performed using a 3.5 mm RMT quadripolar ablation catheter with a 2–5–2 mm spacing (Biosense Webster), either irrigated or non-irrigated as per the operator's preference and location of the PVC. The catheter was maneuvered using the Stereotaxis magnetic navigation system (Stereotaxis, St Louis, MO) with the magnetic force vector directed toward the myocardium to maximize contact force as much as possible.

- Electroanatomic mapping: An EAM was created first with vital anatomic structures such as pulmonic and tricuspid valves, and His bundle identified. LAT map was then generated based on the maximal negative slope of the uni-EGM (-dV/dtmax, filtered at 1–240 Hz) provided by the CARTO mapping system. Attention was paid to make sure that the LAT was complete with a “focal” activation site by mapping the majority to the entirety of the right ventricle.

- Bipolar EGM mapping: local bi-EGM (filtered at 30–400 Hz) was then carefully mapped to refine the focus with the earliest bi-EGM, ignoring-dV/dtmax from this point on.

- Sharpest bi-EGM mapping: The sharpest bi-EGM was further identified with extensive local mapping before ablation.

If spontaneous PVCs were absent, isoproterenol infusion at various rates (2–8 μg/min), calcium chloride infusion, atropine boluses, and/or programmed/burst stimulation were performed. In the cases with presenting ECG showing LBBB morphology, mapping and ablation were first attempted in RVOT if local bi-EGM was 20 ms earlier than the surface QRS. If unsuccessful, or the presenting PVCs had a RBBB morphology, then the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) and the left ventricle (LV) would be mapped and ablated. Based on the location of the earliest activation site in RVOT, that is, the anterior or anteroseptal, late timing of bi-EGM to surface QRS, and ablation in RVOT unsuccessful, the anterior interventricular vein-great cardiac vein (AIV-GCV) area may be mapped if access into the site was achievable. The LV summit area was not accessed.

Ablation power setting was 35–45 watts for non-irrigated and 30–40 watts for irrigated catheter, ensuring adequate power was delivered. Duration of radiofrequency (RF) energy application was variable: up to 30 s if there was no suppression of PVC, and up to 60 s if PVCs were suppressed within the first 30 s, followed by consolidation lesions usually for 30 s at the discretion of the operator. If the last ablation was considered successful, isoproterenol infusion at a rate up to 8 μg/min was administered. If there were no recurrences of PVCs after 30 min, the procedure was deemed successful. If recurrent after multiple attempts of bi-EGM mapping and ablation at different sites over a prolonged time period at each site, the procedure might be considered unsuccessful and terminated at the discretion of the operator.

2.3 Electrogram analyses

The bi-EGM was downloaded as ASCII files from the WorkMate Claris™ recording system (Abbott, Chicago, IL) and analyzed offline digitally (Graphic abstract) after converting to real-time voltage and timing based on a conversion factor of 78 nano-volts per pixel and a sampling rate of 2000 Hz. The EGM was analyzed by two investigators (SYJ and SJ) based on pre-defined criteria for successful vs. unsuccessful group and for five pre-defined parameters (see below) to quantitate the bi-EGM. The PVC with the earliest bi-EGM timing to surface QRS and sharpest initial deflection was selected for the analyses.

2.4 Quantitative parameters

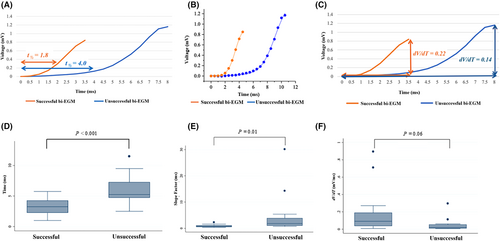

- The half time of activation (measured at the half time point from the onset to the peak of initial deflection of the distal bi-EGM), t½, was measured as a non-weighted parameter (Figure 2A).

- The slope factor, S, was calculated by fitting the data with the Boltzmann equation as a weighted parameter to account for its nonlinearity (Figure 2B, Figure S1).

- Then a linear slope, dV/dt, was calculated as a counter-check parameter against t½ and S, specifically, the peak amplitude of the initial bi-EGM divided by the time from the onset to the peak (Figure 2C).

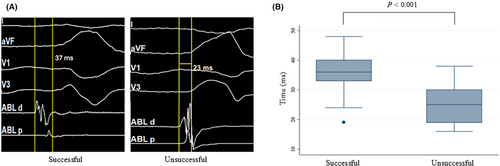

- The time from the onset of the initial bi-EGM to surface QRS, Ts, was measured to define the earliness of local activation, reflecting the distance of the PVC origin or the activation site to the distal bipolar electrodes of the ablation catheter (Figure 3A).

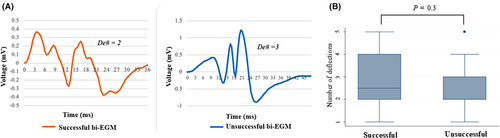

- The number of deflections, De#, was counted to define the degree of fractionation of the focal VA reflecting its further propagation. One deflection is defined as a complete polarity reversal, from positive to negative and vice versa from the baseline. (Figure 4A).

2.5 Clinical follow-up

All patients were followed up post-procedurally via telephonic assessment for any symptomatic recurrences or complications within the first 1–2 weeks. Further clinical follow-ups in 4–8 weeks and 3–6 months included evaluations of symptoms and ECGs. During follow-ups, up to 6 months, no recurrence by symptoms and on ECG in the successful group. Cardiac mobile monitoring was performed as needed based on clinical symptoms.

2.6 Statistical analyses

Data analyses were performed using STATA 17 (STATACorp LLC, College Station, TX). Continuous variables were summarized and reported as mean ± SD and compared between the successful and the unsuccessful groups using unpaired Student's t-test. Categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages and analyzed using the chi-square test. Mean and standard deviation of each parameter were also categorized by location of PVCs among successful ablation cases. A one-way ANOVA test was performed to compare the means for each parameter by PVC location. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to examine predictive accuracy. The cut-off value was determined based on Youden's J statistic. Optimal parameters were calculated by determining whether an observation predicted a positive outcome using a cut-off point of >0.5 for the predicted probability. Maximized parameters were identified by selecting cut-offs that yielded the highest sensitivity. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Baseline demographic characteristics

Out of 74 patients referred to our institution for PVC ablations, 41 consecutive patients were included in this study for having symptomatic antiarrhythmic-refractory idiopathic focal PVC. The average age was 52 ± 14 years, with 17 (42%) being male. The overall mean PVC burden was 21.1 ± 13.3%, with the successful group at 20.2 ± 12.8% and the unsuccessful group at 22.4 ± 14.4%, which were not statistically different. Only one patient had prior ablation. Ventricular systolic function was essentially normal in all patients. The age of the unsuccessful group trended older but was not statistically significant (54.5 ± 11.8 vs. 50.0 ± 15.1, p = 0.3). Otherwise, clinical characteristics overall are well matched between the two groups (Table 1).

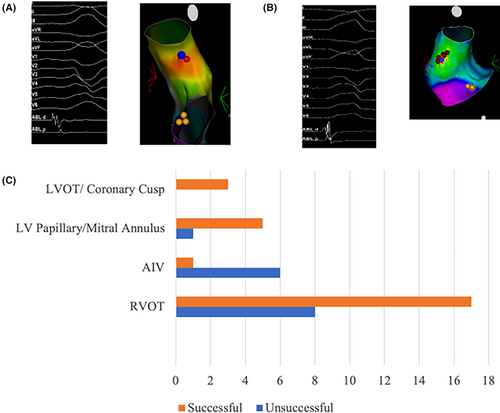

3.2 Electrophysiology study, PVC location and ablation outcome

The mapping and ablation protocol were described in the Methods section. PVC location was determined based on the final successful ablation site and the earliest timing of the distal bi-EGM to the surface ECG (Ts) if successful, or the earliest timing (Ts) only if unsuccessful. They were further categorized into 4 groups based on their anatomic locations: 25 of the cases were located in RVOT, 6 in LV, which includes locations at the mitral annulus and the papillary muscles, 3 in LVOT/coronary cusps, and 7 in AIV-GCV (anterior interventricular vein and great cardiac vein). The overall ablation success rate was 63.4% (26 out of 41 patients). By location, 68% were successful in RVOT, 83.3% in LV (mitral annulus/papillary muscle), 100% in LVOT/cusp, and 14.3% in AIV-GCV (Figure 1C).

3.3 Sharpness of the distal bi-EGM and the relationship to ablation outcome

The initial deflection of the distal bi-EGM is considered to reflect the initial activation of a focal PVC beneath the recording electrodes. To compare the sharpness of the distal bi-EGM between the two groups, the t½ was measured digitally, the slope factor S was obtained by fitting the data with the Boltzmann equation offline, and the linear dV/dt was calculated manually (Figure 2 and Table 2). The t½ is significantly smaller in the successful group as compared to the unsuccessful group (3.1 ± 0.3 vs. 5.9 ± 0.6 ms, p < 0.001), indicating a quicker activation time, thus a sharper deflection (Figure 2A,D). The slope factor S was also significantly different between the two groups (0.8 ± 0.1 vs. 4.8 ± 2.0 ms, p = 0.01), with the smaller slope factor indicating a steeper slope, thus sharper deflection in the successful group (Figure 2B,E). However, the linear parameter dV/dt did not differ significantly between the groups (0.16 ± 0.04 vs. 0.05 ± 0.02 mV/ms, p = 0.06) (Figure 2C,F), consistent with the activation being non-linear.

| Successful | Unsuccessful | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 26 | N = 15 | ||

| Half time of activation, ms (T1/2) | 3.18 ± 0.25 | 5.85 ± 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Slope factor, ms (S) | 0.82 ± 0.09 | 4.83 ± 2.01 | 0.01 |

| bi-EGM to EKG, ms (Ts) | 35.62 ± 1.25 | 25.80 ± 1.64 | <0.001 |

| Linear slope, mV/ms (dV/dT) | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Number of deflections (De#) | 2.65 ± 0.22 | 2.27 ± 0.28 | 0.29 |

3.4 Earliness of the distal bi-EGM to surface ECG and the relationship to ablation outcome

When compared for the earliest timing of the distal bi-EGM at the focal PVC site to the surface ECG, Ts, between the successful and unsuccessful group, it was found that the difference was statistically significant (35.6 ± 1.3 vs. 25.8 ± 1.6 ms, p < 0.001) (Figure 3A,B, and Table 2), with the successful group being earlier.

3.5 Number of deflections of the distal bi-EGM and the ablation outcome

The bi-EGM was further examined for the degree of fractionation by counting the number of deflections it possessed as the fractionated distal bi-EGM is often considered a target for ablation in both focal PVCs and scar VT. The successful and unsuccessful groups showed a similar number of deflections without a statistically significant difference (2.7 ± 0.2 vs. 2.3 ± 0.3, p = 0.22) (Figure 4A,B, and Table 2).

3.6 Comparison of the five parameters among different locations

To evaluate if the distal bi-EGM in successfully ablated cases is truly more a reflection of local electrical activities, the five parameters were then compared among four anatomic locations: RVOT, LVOT, LV, and AIV-GCV. All five parameters (t½, S, Ts, dV/dt and De#) were not statistically different across the four locations with p-values of 0.74, 0.42, 0.94, 0.59, and 0.59 respectively (Table 3).

| Half time of activation, ms (T1/2) | Slope factor, ms (S) | bi-EGM to EKG, ms (Ts) | Linear slope, mV/ms (dV/dT) | Number of deflections (De#) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location (N, p-value) | p = 0.74 | p = 0.42 | p = 0.94 | p = 0.59 | p = 0.75 |

| RVOT (17) | 3.07 ± 1.24 | 0.76 ± 0.47 | 35.12 ± 7.25 | 0.18 ± 0.20 | 2.47 ± 1.18 |

| AIV (1) | 2.25 ± n/a | 0.73 ± n/a | 39.00 ± n/a | 0.03 ± n/a | 3.00 ± n/a |

| LV Papillary/mitral annulus (5) | 3.40 ± 1.65 | 0.81 ± 0.34 | 36.20 ± 5.07 | 0.18 ± 0.30 | 3.00 ± 0.71 |

| LVOT/coronary cusp (3) | 3.75 ± 1.32 | 1.23 ± 0.38 | 36.33 ± 4.93 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 3.00 ± 1.73 |

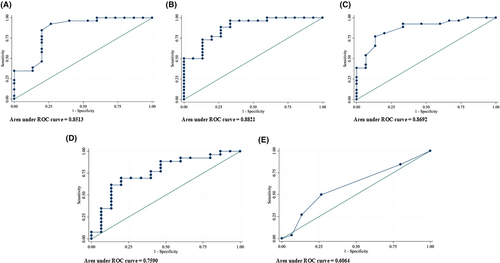

3.7 Predictive values of t½, S and Ts

The predictive values of each parameter were further assessed by constructing receiver-operating characteristic curves (ROC, Figure 5, and Table 4). The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.85 for t½, 0.88 for slope factor S, and 0.87 for Ts, all greater than 0.8, showing good power in predicting successful ablation. An optimal cut-off value of 5.0 ms for t½ yielded a sensitivity of 92.3% and specificity of 73.3%, 1.8 ms for S yielded a sensitivity of 92.3% and specificity of 66.7%, and 33 ms for Ts gave a sensitivity of 92.3% and specificity of 67.7%. However, as the goal of ablation is not to miss any case with a possibly ablatable PVC focus, the cut-off values for achieving 100% sensitivity for our cohort are listed in Table 4 as the maximized parameters, compared with the optimal cut-offs.

| Optimal parameters | Maximized parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

| Half time of activation, ms (T1/2) | 5.00 | 92.31 | 73.33 | 5.75 | 100.00 | 40.00 |

| Slope factor, ms (S) | 1.80 | 92.31 | 66.67 | 2.29 | 100.00 | 40.00 |

| bi-EGM to EKG, ms (Ts) | 33 | 92.31 | 66.67 | 23.00 | 100.00 | 80.00 |

- Note: Optimal parameters were calculated by determining whether an observation predicted a positive outcome using a cut-off point of >0.5 for the predicted probability. Maximized parameters were identified by selecting cut-offs that yielded the highest sensitivity.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Main findings

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the distal bi-EGM using five quantifiable parameters in order to distinguish the sites of successful from unsuccessful ablation of idiopathic focal PVCs and further define the corresponding bi-EGM as near-field and far-field. The key findings are as follows: (1) The sharpness of the initial deflection of intracardiac distal bi-EGM may be better quantified by the half time of activation (t½) and the slope factor (S), but not by the linear slope (dV/dt), supporting the notion that the initial activation is non-linear and voltage dependent. (2) t½, S, and the time from onset of bi-EGM to the surface QRS (Ts) are significantly different between the successful and unsuccessful groups, suggesting these parameters could provide quantitative criteria to differentiate near-field from far-field bi-EGM, aiding in the successful ablations. (3) The difference of Ts between the two groups, when converted into distance based on published conduction velocity in the ventricular myocardium, demarcates a cut-off distance of approximately 4 mm into the myocardium for successful ablation (see discussion below). (4) The degree of fractionations (De#) appears to reflect centrifugal conductions beyond the initial activation from focal PVC origin, and bears no clear implication for distinguishing successful from unsuccessful sites, different from ischemic VT.

4.2 Smaller t½ and S, and earlier Ts may define the “true” near-field bi-EGM for the purpose of successful ablation

Bipolar recording electrodes, closely spaced at 2 mm, can be positioned close to the site of PVC origin. As the “far-field components and noises” encountered at the different and indifferent electrodes are similar,1, 2 therefore subtracted out, the bi-EGM is hence considered to be “near-field and local” with a sharp initial deflection. However, when considering unsuccessful ablation sites, should these bi-EGMs still be considered as near-field? Our data show that the sharpness of bi-EGM, defined by t½, and S, is significantly different between successful and unsuccessful group, with smaller t½, and S found at the successful sites (Table 2 and Figure 2). Additionally, Ts is also significantly earlier in the successful group (Table 2 and Figure 3). The ROC curves of t½, S and Ts have an AUC 0.85, 0.88, and 0.87, greater than 0.8 for good predictive power, suggesting these parameters may be used as practical surrogates to define clinically relevant near-field bi-EGMs, which originate within the thermal field of the radiofrequency energy. The decrease in sharpness and timing at the unsuccessful sites is consistent with a reduction in current because of the inverse relationship over the increased distance that bi-EGM must travel from focal PVC origin to the ablation electrode, same as the well-known path loss phenomenon in signal transmission. Consequently, bi-EGMs at these sites should be considered as far-field.

In contrast, the linear parameter dV/dt, calculated as the peak current of the initial deflection divided by the time, showed a trend of difference between the successful and unsuccessful groups, but not statistically significant, aligning with the understanding that focal PVC activation is non-linear.

4.3 The earliness of bi-EGM may define the depth of PVC origin

This is consistent with the usual effective lesion depth of ~3–5 mm achieved in successful thermal ablation,17, 18 depending on factors such as contact force and tissue types. Therefore, our data imply that PVCs successfully ablated may originate within 4 mm of the myocardium, whereas PVCs that fail to be ablated are likely located deeper than 4 mm. This is in line with a recent study on atrial fibrillation in which a cut-off of 4 mm was determined for differentiating near-field from far-field EGM.19

4.4 “True” bi-EGMs may be less likely affected by anatomic locations

Myocardium thickness and connective tissue content may vary significantly throughout the heart and influence the bi-EGM. RVOT consists mostly of myocardium with variable thickness, while the mitral annulus and papillary muscles may have more fibrous tissue, and probably more so in the AIV/GCV region in addition to smooth muscles.20, 21 However, when comparing the five parameters across anatomic locations, RVOT, LOVT, LV mitral annulus and papillary muscles, and AIV-GCV locations (Table 3) in the successful groups, no significant differences were found among the five parameters over different locations. This indifference may suggest that the distal bi-EGM is less likely affected by the tissue composition when PVC origin is within 4 mm in the myocardium, and similarly useful in guiding ablations at different locations, unlike uni-EGM which has been shown to vary based on PVC locations.6, 7 The cut-off values shown in Table 4 may represent the true near-field bi-EGM and be applicable for the purpose of successful ablation across different anatomic sites.

4.5 Different components of the bi-EGM may reflect different processes

The propagation of activation wavefront is a complex process that depends on multiple factors and gives rise to multiple components in the distal bi-EGM. For ischemic VT ablation, fractionated diastolic bi-EGM, caused by complex conduction processes through the VT diastolic isthmus, is an important target for successful substrate ablation.22-24 Our study, however, found no significant difference in the degree of fraction, defined by the number of deflections between successful and unsuccessful groups (Figure 4). We hypothesize that the initial deflection of the distal bi-EGM reflects the activation of a focal PVC, and the fractionation likely represents how it conducts centrifugally out of its origin. It is probably caused by anisotropic conduction or discontinuities of effective axial resistivity proposed by Spach et al.,4 because of the complex histological and electrical properties of the surrounding myocardium and may not serve as a predictor for successful ablation for idiopathic focal PVCs, in line with the low AUC (0.6, <0.8) of its ROC curve. This is contrary to the customary practice of targeting fractionated bi-EGMs for focal PVC ablation but aligns with the current understanding that idiopathic focal PVCs arise from focal triggered activity or increased automaticity rather than a reentrant mechanism, as seen in ischemic VT.

4.6 Potential clinical application

Potentially, the parameters with good predictive power on ROC curves, namely t½, TS, and S may be integrated into currently available mapping systems. This is probably more likely for t½ and TS, while S may require more computational power. The integration would help validate their clinical utility and, as a result, guide the ablation processes. For example, if the values of these parameters are falling below cut-offs at one site, an alternate location should be quickly considered even without attempting ablation at the current site.

5 LIMITATIONS

Our study has several limitations. It is a single-center retrospective offline study with a relatively small sample size. This may make the data analyses prone to type I error, but our findings align with the underlying physiology of focal PVC. A prospective multi-center study incorporating machine assistance would be beneficial to further validate our results. Additionally, ablation using the magnetic navigation system (Stereotaxis) likely results in less contact force as opposed to manually performed ablations and contributes to a slightly lower success rate as compared with other published data.25 Limited access to the AIV-GCV-LV summit area could have also impacted the success rate, particularly for the RVOT group in which most unsuccessful cases were in the anteroseptal region (Figure 1B), opposite to the AIV-GCV-LV summit area where their true origins may be located. However, they are assigned to RVOT by the definition for this study that a PVC location is determined by the site where the earliest available bi-EGM is identified. Furthermore, we did not conduct concomitant analyses of uni-EGM, as other studies have consistently shown its limited predictive value in guiding successful ablations.6, 7

6 CONCLUSION

The initial activation phase of distal bi-EGM from focal PVCs can be quantitatively assessed using a set of numerical parameters, t½, S, dV/dt, Ts, and De#. Among these, t½ and S can quantitate the sharpness and Ts the earliness of distal bi-EGM for the differences between successful and unsuccessful ablations. These differences may help differentiate the “true” near-field from far-field bi-EGM with an estimated “cut-off” depth of PVC origin at ~4 mm. Prospective studies are needed to validate these findings and assess their applicability in the clinical electrophysiology lab, including the incorporation of t½, TS, and S into a mapping software.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Dr. Peng-Sheng Chen for his insightful discussions on the project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interests to disclose.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data in this study are not openly available because of patient privacy and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.