SARS-CoV-2 infection in children evaluated in an ambulatory setting during Delta and Omicron time periods

Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants and re-emergence of other respiratory viruses highlight the need to understand the presentation of and factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 in pediatric populations over time. The objective of this study was to evaluate the sociodemographic characteristics, symptoms, and epidemiological risk factors associated with ambulatory SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and determine if factors differ by variant type. We conducted a retrospective cohort study of outpatient children undergoing SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction testing between November 2020 and January 2022. Test-positive were compared with test-negative children to evaluate symptoms, exposure risk, demographics, and comparisons between Omicron, Delta, and pre-Delta time periods. Among 2264 encounters, 361 (15.9%) were positive for SARS-CoV-2. The cohort was predominantly Hispanic (51%), 5–11 years (44%), and 53% male; 5% had received two coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine doses. Factors associated with a positive test include loss of taste/smell (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 6.71, [95% confidence interval, CI: 2.99–15.08]), new cough (aOR: 2.38, [95% CI: 1.69–3.36]), headache (aOR: 1.90, [95% CI: 1.28–2.81), fever (aOR: 1.83, [95% CI: 1.29–2.60]), contact with a positive case (aOR: 5.12, [95% CI: 3.75–6.97]), or household contact (aOR: 2.66, [95% CI: 1.96–3.62]). Among positive children, loss of taste/smell was more predominant during the Delta versus Omicron and pre-Delta periods (12% vs. 2% and 3%, respectively, p = 0.0017), cough predominated during Delta/Omicron periods more than the pre-Delta period (69% and 65% vs. 41%, p = 0.0002), and there were more asymptomatic children in the pre-Delta period (30% vs. 18% and 10%, p = 0.0023). These findings demonstrate that the presentation of COVID-19 in children and most susceptible age groups has changed over time.

Abbreviations

-

- CI

-

- confidence intervals

-

- COVID-19

-

- coronavirus disease 2019

-

- EHR

-

- electronic health record

-

- OR

-

- odds ratios

-

- PCR

-

- polymerase chain reaction

-

- SARS-CoV-2

-

- severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

1 INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on nearly every facet of the modern global community. In the United States, there are more than 78 million confirmed cases, and nearly 950 000 deaths as of February 2022.1 Although the prognosis in children remains overall favorable, infection and hospitalization rates increased substantially during the Omicron period, and their role in the transmission of infection to high-risk populations remains important. Since the start of the pandemic, pediatric cases (<18 years of age) have represented 18.9% of the total cumulative cases of COVID-19 in the United States. During the Omicron variant-predominant time period, this proportion increased to 25% of the weekly reported COVID-19 cases.2 The criteria for testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) varies across the United States. While some symptoms of COVID-19 may be similar in children and adults, the frequency of these symptoms varies between these groups.3 There have been studies characterizing the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults, but the pediatric literature is limited. Pediatric studies focus on hospitalized patients, which represent a minority of the population with SARS-CoV-2 infection,4, 5 and many studies were conducted during the early phases of the pandemic, when Alpha strains predominated. Given that most children who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 do not require hospitalization, there remains a need for further investigation into risk factors and symptoms in the ambulatory setting.

The signs and symptoms of COVID-19 in children are similar to other pathogens, including influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and streptococcal pharyngitis.6 The resurgence of seasonal respiratory viruses in 2021 coupled with the emergence of variants and increased infection rates has made the decision of who to test for SARS-CoV-2 has become more challenging. Furthermore, the change in virulence characteristics of newer variants, for example, Omicron's predilection for the upper versus lower respiratory tract for replication,7 may result in altered symptom presentations. The development of variants and potential changes in symptoms highlights the need to increase the understanding of presenting symptoms and risk factors in the pediatric population. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the sociodemographic characteristics, symptoms, and epidemiological risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in children in an outpatient setting and determine if these factors differ by variant predominance.

2 METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of children evaluated in primary care clinics affiliated with Children's Hospital Colorado (CHCO). CHCO is a large academic quaternary care center serving children in the Denver metropolitan area and the greater Colorado area. The affiliated primary care clinics serve approximately 26 000 patients per year. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained through the Colorado Multiple IRB (COMIRB Protocol 21-2805).

Our study population included patients of the three affiliated primary care clinics identified by our institution's clinical scoring algorithm to undergo SARS-CoV-2 testing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) between November 1, 2020 and January 31, 2022. Children presented either in person to the clinic or were evaluated via a nurse phone triage system, with a standardized questionnaire used for both encounter types. Questions included symptoms and epidemiologic risk factors. The scoring algorithm triggered SARS-CoV-2 testing for patients who were either symptomatic or had epidemiologic risk factors (Supporting Information: Digital Content 1. Figure). Children were excluded from the study if they were over 18 years of age at the time of the encounter, did not undergo algorithm scoring, did not have results available, or if the test was done within 90 days of a previous positive test. The SARS-CoV-2 PCR samples were collected by either nasopharyngeal, midturbinate swabs, or saliva. Saliva sample testing became available as a collection method 3 months into the study period in early February 2021. Saliva sample collection was limited to symptomatic patients age 4 and older. Midturbinate swab testing became available 11 months into the study period in October 2021. For this dataset, 23% (n = 512) of the samples were collected by nasopharyngeal, 38% (n = 864) by midturbinate swabs, and 39% (n = 882) by salivary gland. PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 was done at the CHCO microbiology laboratory using Abbott m2000 RealTime assay, Biofire RP 2.1, Cepheid Xpert Xpress, and Simplexa/Diasorin Direct.

Results from the algorithm were entered into the electronic health record (EHR) at the time of the encounter and retrieved for analyses using a secure data reporting workbench (Tableau Version 2020.4.3) run by the hospital's data analytics team. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination status and demographic data were obtained through the EHR, which incorporates parental reports, health-system-based vaccination as well as Colorado Immunization Information System state registry data. Children were characterized as high-risk if they had a comorbidity increasing their risk of complications, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.8 A fully vaccinated individual was defined as a child who received at least two doses of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and at least 2 weeks elapsed since the second dose. A partially vaccinated individual was defined as a child who received only one SARS-CoV-2 vaccine or received a second dose within 2 weeks of the test date. Unvaccinated individuals had not received any SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

The data collection period was further divided into three distinct time periods for variant subanalyses: pre-Delta (before July 2021), Delta (July 1 to November 30, 2021), and Omicron (December 26, 2021 to January 31, 2022). These time periods were established based on when the variant comprised >90% of those sequenced by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.9 Data from December 1–25, 2021 were not included in the analyses given the coexistence of Delta and Omicron variants during this time. The main exposure was SARS-CoV-2 infection based on PCR positivity. The main outcomes of interest included symptoms, epidemiologic risk factors, and variant predominance.

2.1 Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses using χ2 tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests were conducted to assess the demographic and clinical factors of tested patients. Because subjects could have more than one test, subject-level demographic factors were evaluated at the last test encounter for each subject. Clinical factors were evaluated at the test/encounter level. Multivariable logistic regression using generalized estimating equation methods with an autoregressive correlation matrix to account for repeat testing of subjects was used to assess factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity. Covariates were chosen a priori. Spearman correlations were used to assess multicollinearity between covariates. Bivariable analyses comparing factors between variant periods for positive cases were performed using χ2 tests. Cochran–Armitage trend test was used to test for trends across variant periods in asymptomatic, exposed cases. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4. All statistical tests were performed as two-sided tests with a level of significance of 0.05.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Cohort description/sociodemographic characteristics

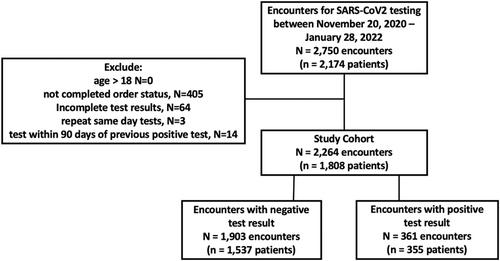

From November 20, 2020 to January 31, 2022, there were 1808 patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR with 344 individuals (19%) having more than one test encounter. There were 2264 total encounters, 361 were associated with a positive SARS-CoV-2 result (Figure 1), with an overall positivity rate of 15.9%. Among the entire cohort, 52% were male, and 51% were Hispanic, with a median age of 5.0 years (interquartile range = 2, 9). Half of the patients were tested during the Delta time period. A higher proportion of testing was performed in children <11 years of age (Table 1). The distribution across different racial groups and ethnicities included in our study was 11% non-Hispanic White, 24% non-Hispanic Black, 51% Hispanic, 9% non-Hispanic other, and 5% unknown. The demographics of children seen at the primary care clinics during this same time frame were 15% non-Hispanic White, 23% non-Hispanic Black, 43% Hispanic, 4% non-Hispanic other, and 14% unknown.

| Demographics and clinical characteristics | Total n (%) | SARS-CoV-2 PCR detected n (%) | SARS-CoV-2 PCR not detected n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient level characteristics | 1808 | 337 | 1471 | |

| Median age (years) at a most recent encounter | 5.0 (2.0, 9.0) | 6.0 (2.0, 10.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 9.0) | 0.10 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <5 | 766 (42) | 135 (40) | 631 (43) | 0.09 |

| 5–11 | 788 (44) | 142 (42) | 646 (44) | |

| ≥12 | 254 (14) | 60 (18) | 194 (13) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 860 (48) | 168 (50) | 692 (47) | 0.35 |

| Male | 948 (52) | 169 (50) | 779 (53) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 191 (11) | 33 (10) | 158 (11) | 0.25 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 434 (24) | 83 (25) | 351 (24) | |

| Hispanic | 920 (51) | 179 (53) | 741 (50) | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 167 (9) | 21 (6) | 146 (10) | |

| Unknown | 96 (5) | 21 (6) | 75 (5) | |

| Vaccination status for COVID at last encounter | ||||

| Not vaccinated | 1661 (92) | 317 (94) | 1344 (91) | 0.26 |

| Partially vaccinated | 41 (2) | 6 (2) | 35 (2) | |

| Fully vaccinated | 106 (6) | 14 (4) | 92 (6) | |

| High-risk medical conditions | 26 (1) | 5 (1) | 21 (1) | 0.94 |

| Encounter level characteristics | 2264 | 361 | 1903 | |

| Visit for COVID-related concern | 1510 (67) | 291 (81) | 1219 (64) | <0.0001 |

| Recent high-risk exposure | 6 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (0) | 0.29 |

| Close contact with a confirmed case | 698 (31) | 227 (63) | 471 (25) | <0.0001 |

| Currently dismissed from school due to illness | 375 (17) | 79 (22) | 296 (16) | 0.003 |

| Household member probable | 329 (15) | 127 (35) | 202 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Fever | 405 (18) | 65 (18) | 340 (18) | 0.95 |

| Loss of taste or smell | 45 (2) | 22 (6) | 23 (1) | <0.0001 |

| Cough | 1,322 (58) | 219 (61) | 1,103 (58) | 0.34 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 277 (12) | 30 (8) | 247 (13) | 0.01 |

| Diarrhea | 203 (9) | 24 (7) | 179 (9) | 0.09 |

| Congestion or rhinorrhea | 1,437 (63) | 203 (56) | 1,234 (65) | 0.002 |

| Fatigue | 448 (20) | 65 (18) | 383 (20) | 0.35 |

| Headache | 288 (13) | 59 (16) | 229 (12) | 0.02 |

| Body or muscle aches | 159 (7) | 29 (8) | 130 (7) | 0.41 |

| Sore throat | 507 (22) | 68 (19) | 439 (23) | 0.08 |

| Asymptomatic | 374 (17) | 66 (18) | 308 (16) | 0.33 |

- Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

3.2 Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection

In bivariable analysis, compared with test-negative children, a higher proportion of children with a positive test had a visit for concern for SARS-CoV-2 infection (81% vs. 64%, p < 0.0001), close contact with a confirmed case (63% vs. 25%, p < 0.0001), dismissal from school due to illness (22% vs. 16%, p < 0.0030), household member of a probable case (35% vs. 11%, p < 0.0001), loss of taste or smell (6% vs. 1%, p < 0.0001), and headache (16% vs. 12%, p < 0.0243) (Table 1). There was no significant difference in age, race/ethnicity, or vaccination status between children testing positive versus negative for SARS-CoV-2. When used as a continuous variable, increasing age was associated with a positive test.

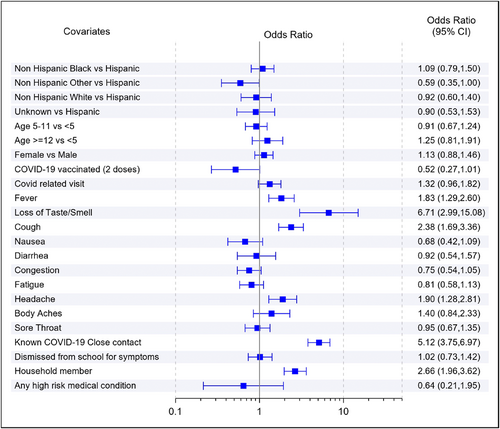

In the multivariable analysis, factors associated with a positive test included fever (odds ratios [OR]: 1.83, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.29–2.60), loss of taste or smell (OR: 6.71, 95% CI: 2.99–15.08), new cough (OR: 2.38, 95% CI: 1.69–3.36), headache (OR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.28–2.81), having a close contact (OR: 5.12, 95% CI: 3.75–6.97), and a household member with probable SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR: 2.66, 95% CI: 1.96–3.62) (Figure 2).

3.3 Differences in a presentation based on the variant period

The percentage of tests with positive results changed throughout the variant periods, increasing from 11% pre-Delta to 12% during Delta and 37% during Omicron (Supporting Information: Digital Content 2. Figure). In bivariable analyses, there were significant differences in age, race/ethnicity, vaccination status, cough, loss of taste or smell, and having an asymptomatic presentation by variant period (Table 2). Among children testing positive, the proportion of those who were non-Hispanic White increased from pre-Delta to Delta and Omicron variants (4% vs. 7% vs. 15%), while non-Hispanic Black positive patients decreased during this same period (35% vs. 23%. vs. 16%, p = 0.0079). A higher proportion of children less than 5 years old tested positive during the Omicron variant period compared with previous periods (p = 0.0361).

| Symptoms | Total positive n (%) | Pre Delta n (%) | Delta n (%) | Omicron n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient level characteristics | 322 | 71 | 134 | 117 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 30 (9) | 3 (4) | 10 (7) | 17 (15) | 0.008 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 75 (23) | 25 (35) | 31 (23) | 19 (16) | |

| Hispanic | 179 (56) | 33 (46) | 80 (60) | 66 (56) | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 19 (6) | 6 (8) | 9 (7) | 4 (3) | |

| Unknown | 19 (6) | 4 (5) | 4 (3) | 11 (9) | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| <5 | 126 (39) | 25 (35) | 43 (31) | 59 (50) | 0.04 |

| 5–11 | 141 (44) | 34 (48) | 66 (49) | 41 (35) | |

| ≥12 | 55 (17) | 12 (17) | 26 (19) | 17 (15) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 157 (49) | 30 (42) | 67 (50) | 60 (51) | 0.45 |

| Male | 165 (51) | 41 (58) | 67 (50) | 57 (49) | |

| High-risk medical conditions | 4 (1) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.39 |

| Vaccination status for COVID | |||||

| Not vaccinated | 305 (95) | 71 (100) | 132 (99) | 102 (87) | 0.0003 |

| Partially vaccinated | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | |

| Fully vaccinated | 13 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 11 (9) | |

| Encounter level characteristics | 327 | 73 | 137 | 117 | |

| Visit for COVID-related concern | 259 (79) | 62 (85) | 110 (80) | 87 (74) | 0.19 |

| Close contact with a confirmed case | 203 (62) | 50 (68) | 84 (61) | 69 (59) | 0.41 |

| Currently dismissed from school | 69 (21) | 13 (18) | 33 (24) | 23 (20) | 0.51 |

| Household member probable | 119 (36) | 29 (40) | 42 (31) | 48 (41) | 0.18 |

| Fever | 62 (19) | 11 (15) | 27 (20) | 24 (21) | 0.62 |

| Loss of taste or smell | 20 (6) | 2 (3) | 16 (12) | 2 (2) | 0.0017 |

| Cough | 201 (61) | 30 (41) | 95 (69) | 76 (65) | 0.0002 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 29 (9) | 4 (5) | 17 (12) | 8 (7) | 0.15 |

| Diarrhea | 24 (7) | 5 (7) | 9 (7) | 10 (9) | 0.82 |

| Congestion or rhinorrhea | 184 (56) | 35 (48) | 78 (57) | 71 (61) | 0.22 |

| Fatigue | 61 (19) | 17 (23) | 27 (20) | 17 (15) | 0.30 |

| Headache | 53 (16) | 12 (16) | 25 (18) | 16 (14) | 0.61 |

| Body or muscle aches | 26 (8) | 9 (12) | 8 (6) | 9 (8) | 0.25 |

| Sore throat | 62 (19) | 11 (15) | 24 (18) | 27 (23) | 0.33 |

| Asymptomatic | 58 (18) | 22 (30) | 24 (18) | 12 (10) | 0.0023 |

- Abbreviation: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

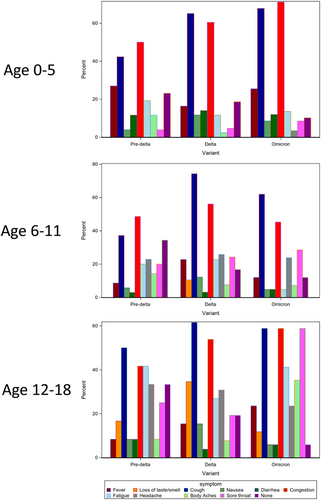

In children with a positive test result, 20 (6%) children experienced the loss of taste or smell, 201 (61%) experienced cough, and 58 (18%) were asymptomatic. There was a significant association between variant period and loss of taste or smell (p = 0.0017), cough (p = 0.0002), and asymptomatic subjects (p = 0.0023). A larger proportion (12%) of children in the Delta period experienced a loss of taste or smell than in either of the other periods (3% pre-Delta and 2% Omicron). A lower proportion of children experience cough in the pre-delta period (41%) than in either of the other periods (69% Delta and 65% Omicron). There were more asymptomatic subjects (30%) in the pre-Delta period than in either of the other periods (18% Delta and 10% Omicron). Of those who were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, either through close contact or a household member with probable infection, there was a significant decreasing trend in the proportion of asymptomatic cases over time periods (pre-Delta 35%, Delta 46%, Omicron 18%, p = 0.0007).

3.4 Reinfection and breakthrough infections following vaccination

Six cases of reinfection (new infection after 3 months of an initial positive test) were identified among 344 individuals who had more than one test. None of the cases with reinfections had any evidence of immunocompromise, immunosuppressing medications, or conditions associated with immune dysfunction. One child with reinfection was recommended to receive prophylactic antibiotics before dental procedures due to a congenital heart condition. All but one patient with reinfection were unvaccinated. Days between reinfections ranged from 99 to 423. Our cohort included 117 fully vaccinated and 48 partially vaccinated patient samples. Among children with breakthrough infections, 79% occurred during the Omicron period.

4 DISCUSSION

This retrospective cohort study of ambulatory children undergoing ambulatory SARS-CoV-2 testing demonstrates that although the presentation of COVID-19 overlaps with other respiratory viruses, loss of taste or smell and exposure are the strongest predictors of SARS-CoV-2 infection across all time periods. This study also reveals differing symptom presentations based on the variant period, as well as differences in predominant race/ethnicity and age groups among children testing positive.

The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in our cohort varied by age and predominant variant period as illustrated in Figure 3. We found an increase in congestion and sore throat in younger children during the Omicron period. Among adolescents, reporting of loss of taste and smell was highest during the Delta period. Children in this age group were less likely to present with fever but had increased reports of sore throat and congestion. Other studies have demonstrated an increase in upper respiratory symptoms and decreased illness severity that may result from lower respiratory tract infection during the Omicron period. One study evaluating the replication competence of different SARS-CoV-2 strains found lower replicative competence of the Omicron variant in human lungs.10 The study also demonstrated enhanced replication of Omicron in the bronchus, which may explain our findings of increased cough during this period compared with the pre-Delta period.

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected minority groups including Hispanic and Black/African American populations.11 In our cohort, the proportion of Hispanic children testing positive remained stable over time (Hispanic children comprised 56% of all SARS-CoV-2 positive cases), but there was a decrease in the proportion of Black/African American children and an increase in the non-Hispanic White testing positive. Similar findings have been observed in other studies.12 We also observed a shift in the age distribution of COVID-19 cases over time, with a higher proportion of children under the age of 5 years testing positive during the Omicron period compared with the Delta and pre-Delta periods, similar to national reports on hospitalization during this time period.13 Reasons for this increased susceptibility are under investigation, with one hypothesis being the variant's high transmissibility, coupled with decreased pre-existing immunity, rendering children more vulnerable to infection than adolescents and adults.14 Our study cohort represents a diverse outpatient sample of children of varying age, race/ethnicity, exposure risk, and symptom presentation. Symptom reporting and other epidemiologic risk factors were systematically collected and reported, and the same protocol was used throughout all evaluated time periods, standardizing testing practices. While data from observational studies may be biased from health-seeking behaviors, these data included in-person as well as telehealth and phone triage encounters, thus capturing a wider spectrum of illness severity. Previous studies have focused on hospitalized children, while these findings provide novel information regarding symptom presentation in outpatient children.

Although vaccination status was included in these analyses, it is important to note that there were only 117 fully vaccinated children at the time of testing, representing just 5% of the entire cohort of patients. The vaccine was not approved for children 12 and over until May 2021 which was close to the beginning of the Delta variant and 6 months into this study period. Due to the overall low number of fully vaccinated patients and the cohort age and timeframe this study took place, we are unable to evaluate the effects of vaccination on the clinical presentations in our study.

5 LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations of our single-center retrospective study. Caution must be taken when interpreting the symptom data in this study as the subset of patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test and a specific symptom, like loss of taste and smell, the number of patients is small. The prevalence of other respiratory viruses dropped significantly throughout the second half of 2020 and the first half of 2021, returning during the Delta predominant period. Our cohort was only tested for SARS-CoV-2, so we are unable to compare our SARS-CoV-2 positive group with other specific viruses or evaluate how co-infection impacted the clinical presentation. Next, the change in the age distribution of SARS-CoV-2-positive children over time may have impacted the change in symptom presentation. For example, younger children and their guardians may be unable to identify symptoms such as loss of taste and smell, headache, and sore throat, so we evaluated symptoms over time in stratified analyses. The noted lower rates of anosmia and ageusia reported during the Omicron predominant period, therefore, may be more of a reflection of a higher proportion of younger children being infected, rather than a true difference in Omicron presentation. Finally, testing practices changed over the course of the pandemic, with increased testing during the Omicron period when transmissibility and positivity were higher within the pediatric population, and when other respiratory viruses were circulating, compared to the other variant periods. This change in testing practices could also potentially impact our study findings.

6 CONCLUSION

While symptoms from SARS-CoV-2 infection are generally not distinguishable from other respiratory viruses, we observed a change in a presentation by variant period. Loss of taste and smell and close contact with a positive case remained the strongest predictors for infection across all time periods. Additional studies are needed to further elucidate the mechanisms for increased susceptibility and change in presentations of SARS-CoV-2 infection in younger children with newer variants and examine the effect of vaccination on illness presentation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Hana Smith and Dr. Allison Mahon conceptualize and designed the screener algorithm and helped create the collection registry. Dr. Hana Smith, Dr. Allison Mahon, and Dr. Suchitra Rao created the initial study design. Dr. Hana Smith, Dr. Allison Mahon, and Dr. Suchitra Rao drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication. Angela Moss helped with the study design, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript, giving final approval for the version to be published. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Suchitra Rao reports prior grant support from GSK and Biofire. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.