Hit and run oncogeneses in head and neck cancers requires greater investigation

Peter Goon, Martin Goerner, and Holger Sudhoff are senior authors.

Abstract

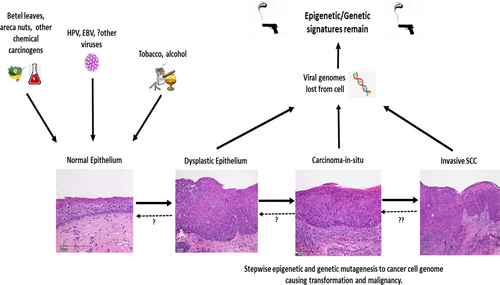

Head and neck cancers are unique in so far that two major oncogenic viruses, Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and Human papillomavirus (HPV) infect adjacent anatomy and cause nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal cancers, respectively. Dominant recognized carcinogens are alcohol and tobacco but some head and neck cancers have been found to have mixed carcinogens (including betel leaf, areca nuts, slaked lime, viruses, etc.) involved in their oncogenesis and conversely, groups of patients with unknown or less dominant carcinogens involved in their development. These cancers may have had viral involvement in the past but then lost most of their viral nucleic acids (be they DNA and/or RNA) below a detection threshold, thus rendering them virus-negative. Some of these virus-negative tumors appear to have mutagenic signatures associated with virus-positive cancers, for example, from the APOBEC defense mechanism which is known to mutate viral nucleic acids as well as cause collateral damage to host DNA, with subsequent development of strongly viral prejudiced mutational signatures. These mechanisms are likely to be less efficient at oncogenesis than traditional EBV and HPV oncogenes directly driving mutagenesis, thus accounting for the smaller frequencies of these cancers found. More profound investigations of these unusual tumors are warranted to dissect out these mechanistic pathways.

Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) are two of the most oncogenic viruses in the world and are estimated to be collectively responsible for approximately 10% of the total annual worldwide cancer burden, and account for 500 000 deaths1-3 per annum. These two DNA viruses have been definitively and causally associated with certain head and neck cancers that is, nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) with EBV, and oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) with HPV, and especially uniquely, these anatomically and structurally adjacent areas in the pharynx.

The concept of virus “Hit and Run”(H&R) in carcinogenesis and malignancy was first mentioned by Skinner in 19764 when describing the transformation of primary hamster embryo fibroblasts by Herpes simplex virus 2 in vitro. The search for the viral cause of cervical cancer led investigators metaphorically up the wrong garden path, as team after team chased down HSV as the cause. 70%−80% of all cervical cancers contain integrated HPV DNA5 (as do similar frequencies of HPV + OPC),6 but EBV + NPC tend to remain unintegrated from the cellular genome (episomal viral forms).7 This important point gives us strong clues that the biological pathways driving these viral cancers are not necessarily identical even within a “virus positive” group, and that there are likely to be significant differences within and without currently accepted oncogenic pathways.

For example, stricter stratification of HNSCC subgroups has revealed a group of HPV-negative oral cavity cancers with few or silent copy number alterations or mutations. This unusual group usually involve female patients, they are very young (<40 years) or elderly (>70 years) with some history of smoking and little/no alcohol intake.8 Prognosis is better than the usual HPV-negative head and neck cancer patient, and similar to the HPV+ patient. Is it possible that HPV itself (or some other pathogen(s)) has caused sufficient genetic instability and sustained significant key mutations that allow maintenance of the malignant phenotype without detectable viral oncogenes being present? Why not?

We suggest that HPV (or EBV or other unknown viruses) may be able to function in this manner, and that these mechanisms may be much less efficient than currently known and accepted pathways, thus accounting only for a small number of cancers of that type. EBV in particular, encodes >85 genes in its genome, and the functions of many of these are as yet unclear. Could viruses be acting in concert with other carcinogens to drive the cell toward transformation or subsequent malignancy? It is eminently logical that two or more important risk factors with strong oncogenic drive can occur in certain groups of patients and that those cancers would have different oncogenic pathways compared to groups with just one or other risk factors. Focal infection and latency are known features of EBV and likely HPV as well,7, 9 the two viruses associated causally with head and neck cancers. These interesting features therefore suggest that the very low copy numbers found in latent infections may confound detection of these viruses and lead to an erroneous conclusion that a tumor is wrongly classified as virus negative.

Again using head and neck cancer as an example, there appears to be evidence that there is a group of HPV + HNSCC patients with heavy smoking (>10 pack years) and/or heavy tobacco/betel leaf/areca nut chewing, and that all the risk factors appear to be causing their typical signature mutations and driving the cell oncogenically with a mixed additive effect.10, 11 Genomic analyses using WES from India demonstrated that the mutational burden amongst HPV + HNSCC (mostly oral SCCs) with the added mutational oncogenic drive of betel quid+/- tobacco chewing did not show significantly different mutational burdens compared to the larger group of HPV− HNSCC,12 demonstrating that the mutagenic effects of those factors were added to the HPV+ fraction (which is usually much less than the HPV− fraction).

If HPV or EBV are the main oncogenic viruses involved in the carcinogenesis of some of these virus-ve and tobacco/alcohol-ve groups, then we would expect to see some residual epigenetic or genetic (i.e., APOBEC3 [apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like], ADAR [adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 1], etc.) patterns left on the cancer cell genome within the cell. These specific patterns indicate the molecular signatures of a specific virus' activity, the so-called “smoking guns.” Recent studies have revealed patterns for both EBV+ and HPV + HNSCC.13 Baker et al.14 have recently provided convincing mechanistic evidence that reactivation of latent BK polyomavirus in patients strongly increases the risk of developing bladder cancer through a H&R mechanism via the APOBEC3 antiviral mechanism. HPV studies in animal models15 and in vitro16 also provide suggestive evidence for the possibility of H&R oncogeneses. These studies provide compelling evidence that the concept of a viral “Hit and Run” is not as far-fetched as previously thought (see Figure 1).

APOBEC mutagenic signatures have been found to be heavily skewed toward the HPV+ head and neck cancer fraction (98%) compared to 76% of HPV− head and neck cancers.17 This interesting paper highlights that even in head and neck cancers that are designated HPV− with viral RNA transcripts <100 per 100 million, 76% of these HPV− cancers carried detectable APOBEC signatures. This is supportive evidence that our best available methods of classifying tumors as HPV+ or −, and determining dominant mutagenic patterns in tumors lie on a detectable/diagnostic spectrum.

Testing these hypotheses requires animal models to follow changes after viral infection, and more importantly, prospective longitudinal human studies with repeated DNA/RNA/epigenetic sampling from affected sites during the dysplastic phase, carcinoma-in-situ, frank invasion, and metastatic phases. Finding evidence for this mechanism and proving its importance in the viral causality of certain cancers (fulfilling Koch's & Bradford-Hill criteria), will be more difficult than proving a mere association, but will increase the importance of prophylactic vaccines (available for HPV but not for EBV so far) and also specific antiviral therapies against these ubiquitous viral pathogens in ultimately preventing important cancers and saving lives.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Associate Professor Peter Goon, Professor Holger Sudhoff, and Dr. Martin Görner were involved in all aspects of the writing of this article, specifically in the conceptualization, data collation, analyses, and visualization. Dr Peter Goon performed the majority of the writing and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study