Relationship of herpesvirus (HSV1, EBV, CMV, HHV6) seropositivity with depressive disorder and its clinical aspects: The first study in children

Abstract

Infections can lead to the onset of mood disorders in adults, partly through inflammatory mechanisms. However pediatric data are lacking. The aim of this study is to evaluate the relationship between depressive disorder and seropositivity of herpes virus infections in children.

The sample group consisted of patients diagnosed with depressive disorder according to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria and healthy volunteers, being between 11 and 18 years with clinically normal mental capacity. All children completed DSM-5-Level-2 Depression Scale, DSM-5-Level-2 Irritability Scale, DSM-5-Level-2 Sleep Scale, DSM-5-Level-2 Somatic Symptoms Scale. The levels of anti-HSV1-IgG, anti-CMV-IgG, anti-EBNA, and anti-HHV6-IgG were examined in all participants. Patients with an antibody value above the cut-off values specified in the test kits were evaluated as seropositive. The mean age was 15.54 ± 1.57 years in the depression group (DG), 14.87 ± 1.76 years in the healthy control group (CG). There were 4 boys (11.2%), 32 girls (88.8%) in the DG, 9 boys (21.9%) and 32 girls (78.04%) in the CG. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of the presence of seropositivity of HSV1, CMV, EBV, and HHV6. HHV6 antibody levels were significantly higher in the DG (p = 0.000). A significant positive correlation was found between HHV6 antibodies and DSM-5 level-2 somatic symptoms scale score. HHV6 antibody levels were found to be significantly higher in patients with existing suicidal ideation in the DG (n = 13) compared to those without existing suicidal ideation in the DG (p = 0.043). HHV6 persistent infections may be responsible for somatic symptoms and etiology of suicidal ideation in childhood depressive disorder.

1 INTRODUCTION

Depressive disorder is recognized as one of the leading causes of disability worldwide.1 In a meta-analysis evaluating the data of 41 studies from 27 countries, the prevalence of any depressive disorder was found to be 2.6%.2 The prevalence of the depressive disorder in elementary school children in Turkey has been reported as 1.06%.3 However, the rate is between 4% and 12% in studies conducted during adolescence.4, 5 Depressive disorder is associated with both medical morbidity and mortality and has been linked to significant impairments in educational, occupational, and social functioning.6 Therefore, it is important to investigate the etiology of depressive disorder. In several studies, the depressive disorder has been associated with environmental factors, toxins, stress, and infections.7 In the study conducted by Benros et al.,8 hospitalization due to autoimmune disease increased the risk of mood disorder diagnosis by 45%, and a history of hospitalization for any infection increased the risk of subsequent diagnosis by 6%. It was found that approximately one-third (32%) of the participants diagnosed with mood disorders were hospitalized previously due to infection, and 5% of them were hospitalized due to an autoimmune disease. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections have been evaluated as independent and synergistic risk factors for mood disorders. The findings were interpreted in accordance with the general immunological response affecting the brain in subgroups of patients with mood disorders; however, an investigation of how the immunological process affects the brain and whether it is a causal relationship or an epiphenomenon with underlying genetic, psychological, or nonimmune mechanisms has been suggested. In the study by Goodwin et al.,9 infections in the early period of life increased the risk of depressive disorder by approximately four times. Infections can lead to the onset of mood disorders, partly through inflammatory mechanisms. Proinflammatory cytokines triggered in response to infection can increase indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity, cause tryptophan to be metabolized along the kynurenine pathway, and reduce plasma tryptophan levels required for serotonin synthesis. Also, imbalances in kynurenine metabolites acting as N-methyl-d-aspartate agonists or antagonists may contribute to depression onset by altering glutamatergic neurotransmission.10-13

This study aims to investigate whether herpesvirus infections (seropositivity) are related to pediatric depressive disorder.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study involved pediatric patients who visited Manisa Celal Bayar University Faculty of Medicine, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Outpatient Clinic, and Child Health and Diseases Outpatient Clinic. Ethical approval was obtained from the Manisa Celal Bayar University Health Sciences Ethics Committee. Our study was supported by the Manisa Celal Bayar University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (Project number: 2019-148). A written consent form was obtained from all parents and all children aged 13−18.

The study group consisted of patients diagnosed with depressive disorder according to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria and healthy volunteers. There were 35 subjects in the patient group. Inclusion criteria were as follows: between the ages of 11 and 18 years, who volunteered to participate in the study, and a clinically normal mental capacity. Subjects with chronic diseases, psychotic disorders, autistic spectrum disorders, and mental retardation, or participants with symptoms of viral infection were excluded from the patient group. There were 41 children in the healthy control group (CG). Inclusion criteria were similar to those for the patient group. Individuals with active psychopathology according to the applied Computerized Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) or with a history of mental illness, any chronic disease, or participants with symptoms of viral infection were excluded from the study.

K-SADS-PL was administered to all children participating in the study for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders.14-16 In addition, all children completed the DSM-5 Level-2 Depression Scale, DSM-5 Level-2 Sleep Disorders Scale, and DSM-5 Level-2 Somatic Symptom Scale.17-20

The levels of anti-HSV1-IgG, anti-CMV IgG, anti-EBNA, and anti-HHV6 IgG were examined in the patient and CG. Patients with an antibody value above the cut-off values specified in the test kits were evaluated as seropositive.21

2.1 Test procedure

- 1)

For anti-HHV6 IgG detection, the Sunred® commercial kit (Shanghai Sunred Biological Technology) with a pair of antibodies for sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) coated with HHV6 antigen was used. The test was carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The washing process was performed in the Combiwash® washing device (Human GmbH), and the optical densities of the test wells were measured at 450 nm using the Chromate 4300® reader (Awareness Technology). The results were obtained in ng/ml.

- 2)

Anti-HSV1 IgG was detected using an ELISA-based commercial kit (Orgentec Diagnostika GmbH) and a fully automated ELISA analyzer (Alegria®) from the same manufacturer's. The results were evaluated semiquantitatively based on the manufacturer's recommendations with a cut-off value of 25 U/ml.

- 3)

For anti-EBV EBNA IgG and anti-CMV IgG tests, Vidas II® (bioMérieux SA), a fully automated analyzer based on enzyme-linked fluorescent-assay detection, was used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Based on the manufacturer's guidelines, positive cut-off values with 0.21 test value for anti-EBV EBNA IgG and 6 AU/ml for anti-CMV IgG were accepted in the evaluation of the results.

2.2 Evaluation tools

- 1.

Sociodemographic data form: The form was created by the authors to determine the sociodemographic characteristics of the children in the study.

- 2.

Interview Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age (6−18 years) Children-Present and Lifetime Version-Turkish Version (K-SADS-PL): It is a semistructured interview chart used to determine mental disorders in children and adolescents. A Turkish validity and reliability study has been conducted.14-16

- 3.

DSM-5 Level 2 Depression Scale for 11−17-year-old children: It is a 14-item PROMIS Depression Short Form that evaluates the depression domain in children and adolescents. Each item asks the child to rate the severity of depression in the last 7 days. The total score can range from 14 to 70 points. Higher scores indicate that the severity of depression is higher. It has been adapted to Turkish.17, 18

- 4.

DSM-5 Level 2 Sleep Disorders Scale for 11−17-year-old children: It is an 8-item PROMIS Sleep Disorders Short Form that specifically evaluates sleep disorders in children and adolescents. With each item, the child is asked to evaluate the severity of sleep disturbance in the last 7 days. The total score can range from 8 to 40 points. Higher scores indicate the presence of a more severe sleep disorder. It has been adapted to Turkish.17, 19

- 5.

DSM-5 Level 2 Somatic Symptom Scale for 11−17-year-old children: The patient health questionnaire for evaluating somatic symptoms in children and adolescents is an adaptation of the Patient Health Questionnaire Physical Symptoms (PHQ-15). Each item requires the child to rate the severity of somatic symptoms over the past 7 days. The total score can range from 0 to 26. Higher scores indicate that the somatic symptoms are more severe. It has been adapted to Turkish.17, 20

2.3 Statistical analysis

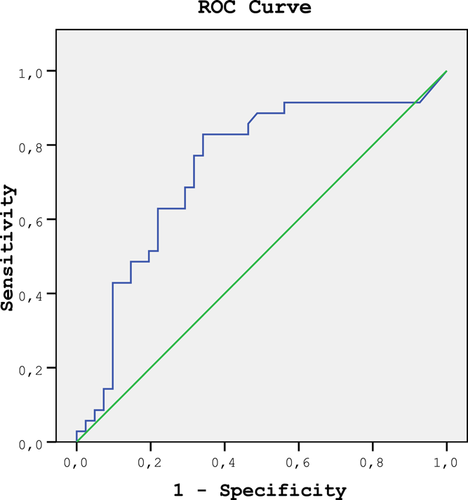

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; SPSS Inc.). Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; the categorical variables of sociodemographic data, clinical data, and scales are expressed as percentages and numbers. Student's t-test was used in independent groups to compare two groups with a normal distribution for numerical variables, and a nonparametric Mann−Whitney U test was used for data without normal distribution. χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare categorical data. To determine the direction and level of the relationship between numerical variables, Pearson's correlation test was used for data with normal distribution, and Spearman's correlation test was used for data without normal distribution. The strength for distinguishing between control and clinical samples was shown by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

3 RESULTS

In this study, 35 pediatric patients with a diagnosis of depression and 41 healthy control children were included. The mean age was 15.54 ± 1.57 years in the depression group (DG) and 14.87 ± 1.76 years in the healthy CG. There were 4 boys (11.2%) and 32 girls (88.8%) in the DG and 9 boys (21.9%) and 32 girls (78.04%) in the CG. There was no statistically significant difference in terms of age and gender between the two groups. In addition, no significant difference was found between the education and employment status of the mothers and fathers (Table 1).

| Depressive disorder (n = 35) | Healthy control group (n = 41) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 15.54 ± 1.57 | 14.87 ± 1.76 | 0.087 |

| Gender (male/female) | 4/31 | 9/32 | 0.225 |

| Parental relationship statusa (together/divorced) | 28/5 | 35/6 | 0.950 |

| Working/nonworking mothera | 12/21 | 18/23 | 0.511 |

| Working/nonworking fathera | 32/2 | 41/0 | 0.115 |

| Maternal educational level | 0.542 | ||

| Primary school | 13 | 20 | |

| Middle school | 10 | 11 | |

| High school/university | 12 | 10 | |

| Paternal educational level | 0.404 | ||

| Primary school | 15 | 19 | |

| Middle school | 9 | 5 | |

| High school/university | 11 | 17 | |

| DSM 5 Level 2 Depression Scale Scores | 55.11 ± 12.71 | 23.80± 6.87 | 0.000 |

| DSM-5 Level-2 Sleep Disorders Scale Scores | 27.37 ± 8.49 | 15.53± 478 | 0.000 |

| DSM-5 Level-2 Somatic Symptom Scale | 10.97 ± 4.68 | 4.92 ± 2.67 | 0.000 |

| HSV-1 IgG (ng/ml) median (min−max) | 81 (2.1−201) | 62.7 (1.1−201) | 0.415 |

| EBNA-IgG (AU/ml) median (min−max) | 4.9 (0−7.6) | 5.78 (0−8.1) | 0.128 |

| CMV-IgG (AU/ml) median (min−max) | 44 (3−95) | 39 (3−140) | 0.187 |

| HHV6- IgG (ng/ml) median (min−max) | 2.48 (0−22.2) | 1.7 (0−8.06) | 0.000 |

- Note: Italic values are considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

- a Deceased parents were not included in the statistics.

In the DG, the number of seropositive patients was 25 (71.4%) for HSV1, 29 (82.9%) for EBV, 33 (94.2%) for CMV, and 32 (91.4%) for HHV6. In the CG, it was 29 (70.7%) for HSV1, 39 (95.1%) for CMV, 39 (95.1%) for EBV, and 38 (92.7%) for HHV6. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of seropositivity.

When herpes virus antibody levels were compared, it was found that the HHV6 antibody level was significantly higher in the DG than in the CG (p = 0.000). There was no significant difference in the antibody levels of CMV, HSV1, and EBV (Table 1).

Correlation analysis was performed for herpes virus antibody levels and DSM-5 Level 2 Depression Scale, DSM-5 Level 2 Sleep Disorders Scale, and DSM-5 Level 2 Somatic Symptom Scale scores. A significant positive correlation was found between the HHV6 antibody level and DSM-5 Level 2 Somatic Symptom Scale score (Table 2).

| HSV-1 IgG IU/ml | EBV IgG AU/ml | CMV IgG AU/ml | HHV6 IgG ng/ml | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM 5 Level 2 Depression Scale Scores, r | 0.048 | 0.094 | 0.041 | 0.167 |

| DSM-5 Level-2 Sleep Disorders Scale Scores, r | 0.134 | 0.142 | 0.010 | 0.098 |

| DSM-5 Level-2 Somatic Symptom Scale, r | 0.066 | 0.038 | 0.007 | 0.358* |

- Note: Pearson correlation test.

- * p = 0.001.

In the DG, 11 patients had psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorder (n = 7), conduct disorder (n = 3), and tic disorder (n = 1). There was no statistically significant difference in herpes virus antibody levels between depressive patients with and without a comorbid diagnosis. There was a history of suicide attempts in 15 patients in the DG. Seven patients attempted suicide in the last month. There was no significant relationship between herpes virus antibody levels and a history of suicide attempts in the DG (Table 3).

| Group with suicide attempt (n = 15) | Group without suicide attempt (n = 20) | p | Group with suicidal ideation (n = 13) | Group without suicidal ideation (n = 22) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 IgG (IU/ml) median (min−max) | 143.9 (2.10−201) | 58.15 (2.5−201) | 0.384 | 19.15 (2.1−164.6) | 96 (2.5−201) | 0.068 |

| EBNA-IgG (AU/ml) median (min−max) | 5.5 (0−7.6) | 4.76 (0−7.58) | 0.763 | 6.03 (0−7.6) | 4.6 (0−7.58) | 0.172 |

| CMV-IgG (AU/ml) median (min−max) | 45 (3−95) | 43 (18−73) | 0.395 | 38 (3−46) | 44 (3−95) | 0.986 |

| HHV6-IgG (ng/ml) median (min−max) | 2.42 (0−22.26) | 2.56 (0−4.69) | 0.726 | 2.89 (1.55−22.26) | 2.48 (0−5.72) | 0.043 |

- Note: Italic values are considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

A total of 13 patients in the DG had suicidal ideation at the time of the interview. HHV6 titer was significantly higher in patients with existing suicidal ideation than in patients without current suicidal ideation in the DG (0.043) (Table 3).

With the ROC analysis of the HHV 6-Ig G that included the healthy group and the group diagnosed depression through a clinical interview, the area under the ROC curve was measured at 0.738 (p < 0.001). (Figure 1).

4 DISCUSSION

In our study, the HHV6 antibody level was significantly higher in children with the depressive disorder than in healthy control children. Also, the HHV6 antibody level was significantly higher in children with suicidal ideation than in children without suicidal ideation in the DG. A positive correlation was found between the HHV6 antibody level and DSM-5 Level 2 Somatic Symptom Scale score. The relationship between HHV6 and mental disorder has been observed in some studies; however, thus far, all studies involved adult patients. This is the first study to include children.

HHV6A/B is known as a neurotropic virus that can remain latent in the central nervous system and other tissues, and mental or cognitive disorders may occur during reactivation.22-24 HHV6A/B late protein and viral DNA levels were found to be significantly higher in patients with depressive disorder and bipolar disorder than in healthy controls in the the postmortem posterior cerebellum.25 Production of the HHV6 latent protein SITH-1 in olfactory astrocytes was associated with apoptosis of olfactory bulb cells along with symptoms that may be associated with depressive disorder.26 Olfactory bulb volume was smaller in patients with a diagnosis of the depressive disorder compared with healthy controls.27, 28 HHV6A/B can also infect various cells of the immune system. Infection of these cells leads to the production of chemokines and various cytokines, resulting in neuroinflammation.29

The relationship between depressive disorder and inflammation has been identified in several studies.30-36 Whether infections trigger depression or depression predisposes individuals to infections is an important question. One study found that the expression of inflammation-related genes was increased and that the expression of antiviral-related genes was decreased in adolescents with clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms compared with their peers with lower levels of depressive symptoms. Clinical and subclinical depression has also been associated with altered immune system function due to increased circulating levels of inflammatory markers and weakened immunity to viral infections.37

In our study, no relationship was found between CMV, HSV1, and EBV seropositivity or antibody levels and depressive disorder. In a follow-up study by Markkula et al.38 on a sample representing the general population of individuals over 30 years old in Finland, no significant relationship was observed between baseline CMV, HSV1, and EBV antibodies and the incidence of depressive disorder. Similarly, in a follow-up study by Simanek et al.39 on a sample of individuals over the age of 18 years, CMV and HSV1 seropositivity detected in the first evaluation was not associated with depressive disorder detected in the second evaluation performed 1 year later. However, among those who were seropositive for CMV, each unit increase in IgG antibody levels detected at the initial evaluation was associated with a 26% greater likelihood of depression at the second follow-up.

Some reports found that CMV seropositivity was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of depression in adult women, and high CMV antibody level was associated with an increased likelihood of mood disorders in women.40, 41 Gale et al.42 evaluated the relationship between depression and viral exposure using data about depression status, antidepressant use, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, HSV1, HSV2, HIV, and CMV and sociodemographic variables in a population sample. There was no association with hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and HSV1; however, HSV2 was associated with the risk of depression. Higher levels of cytomegalovirus antibodies in CMV-seropositive subjects have been associated with depression. In a study involving adolescents, depressive symptoms were found to be associated with EBV reactivation in EBV-positive female adolescents but not male adolescents.43 In our study, differences in the results may be attributed to age, gender, and our status as a developing country. In Europe and Asia, HSV1 seroprevalence is around 32.5%−50.0% and 74.4%−76.5% in children and adults, respectively, and its seroprevalence has been shown to increase with age.44, 45 The CMV reactivation rate is low in childhood, and the rate is increased among women aged 50 years and over.46 Overall, the seroprevalence of HHV6 is around 90% at the age of 2 years or younger,47 increases during infancy, and remains high until the age of 60 years.48 Unlike other herpes viruses, the possible higher frequency of HHV6 infections in the first 2 years of age and higher reactivation rate in childhood with higher antibody level may explain the HHV6-related findings in our study. In previous studies of both CMV and EBV, the relationship between female gender and depressive disorder was evident.41, 43 However, in our study, the female gender predominance in both groups may affect the statistical significance of this difference. In some studies, a high prevalence has been suggested as a reason why infections do not appear to be risk factors for common mental disorders.38, 49 Therefore, the high seroprevalence in both the case and CG may account for our results. In addition, the seroprevalence of herpes viruses is higher in the Turkish population, and differences between countries have been reported.50 These findings may explain the contradictory data between the literature and our study.

Except for the very young, CMV seroprevalence is higher in females and is associated with a higher incidence of infection in females compared with adult males of a similar age.46 Among adults under 45 years of age, the level of HSV1 antibodies increases with reactivation and is high especially in CMV-seropositive patients.51 Therefore, the association between CMV antibody elevation and female gender in some adult studies but not our study may be explained by these findings.

The cross-sectional nature of our study is a limitation. Observational studies are needed to establish the causality relationship. The pediatric sample of this study might miss major population of depressive patients as it is the most common at the of 20−40 years due to its cross-sectional nature. Furthermore, the lower number of male patients compared with female patients does not reflect the general population. The number of reactivations in patients with persistent infection could not be determined. In addition, due to the use of ELISA as an analytical tool, HHV6A and HHV6B could not be distinguished. Viral infections can be asymptomatic and seronegative in the acute period and cannot be diagnosed. This is another limitation of our study. The association between viral infections and mood disorders was based on antibody levels in our study and in previous reports. However, examining the relationship between evidence-based active infections/reactivation and mood disorders will give a more accurate idea about causality.

In conclusion, HHV6 persistent infection may be responsible for the somatic symptoms and etiology of suicidal ideation in childhood depressive disorder. Studies are needed to determine the causal relationship.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Semra Şen and Şermin Yalın Sapmaz worked together on study design, ethical approval, patient enrollment, statistical analysis, data collecting, writing the article. Hasan Kandemir took part in patient enrollment. Aylin Deniz Uzun took part in patient enrollment, clinical interviews with all of the participants, and data collectng. Talat Ecemiş took part in analysis of serum specimens. Semra Bayturan and Şermin Yalın Sapmaz are mentioned as the first author because of the equality in the study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was funded by Manisa Celal Bayar University Department of Scientific Pojects (Project number: 2019-148).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Celal Bayar University Health Sciences Ethics Committee (16/10/2019-20:478.486). Informed consent was signed for all study participants and when the participant was under 13 years old, the parent signed the informed consent for him.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.