Human monkeypox outbreak in 2022

1 INTRODUCTION

A recent case of monkeypox was identified in the UK on May 6, 2022, in a person who had been to Nigeria, where the disease is prevalent and had symptoms consistent with monkeypox. On May 4, the individual returned to the United Kingdom, bringing the first case of the epidemic to the country. On May 15, four new laboratory-confirmed cases of vesicular rash infection were reported among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM). As of May 11, 2022, a systematic effort to identify exposed contacts in medical settings, the community, and on international flights was in progress. These people were monitored for 21 days after their most recent disease exposure. Even though the origin of the virus in Nigeria is unknown, there is still a possibility of continuous transmission in the country. Monkeypox is a rare viral zoonosis that is native to central and western Africa and has just recently appeared in the UK. According to World Health Organization (WHO), around 12 countries have all documented cases of monkeypox as of May 13–21, 2022. A few cases of MSM have been documented. Some instances have also been documented among those who reside in the same home as the affected person. It should be highlighted that according to WHO, individuals most at risk are those who have had close personal contact with someone who has monkeypox, and this risk is not limited to MSM. None of these people reported any recent travel to central or west African nations where monkeypox is widespread, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo or Nigeria.1 Extremely uncommon is the finding of confirmed and probable cases of monkeypox without direct travel linkages to an endemic location. Until recently, monitoring in nonendemic areas was limited, but it is currently rapidly expanding. In the next weeks, the WHO expects further cases to be recorded in non-endemic locations.

2 VIROLOGY

Monkeypox virus (MPV or MPXV) is a double-stranded DNA zoonotic virus that causes monkeypox in humans and other animals. Monkeypox virus is a member of the family Poxviridae, genus Orthopoxvirus. Additional members of this genus include variola virus (VARV), vaccinia virus (VACC), ectromelia (mousepox) virus, and cowpox virus (CPX). It is neither an ancestor nor a descendant of the variola virus, which causes smallpox.2 Naturally, occurring smallpox has been eradicated since 1977, in part because the variola virus was an obligate human disease with no nonhuman animal reservoir. MPXV, on the other hand, is a zoonotic virus that is endemic throughout West Africa and the Congo Basin. MPXV virions are ovoid or brick-shaped particles surrounded by a geometrically corrugated lipoprotein outer membrane, like other orthopoxviruses. MPXV sizes typically vary from 200 to 250 nm. The membrane bond, as well as the densely packed core containing enzymes, a double-stranded DNA genome, and transcription factors, are protected by the outer membrane.3

Monkeypox has a milder rash and a lower-case fatality rate than smallpox, but in the absence of quick treatment, the case fatality rate for monkeypox might approach 10%.4 The strains in Central Africa are more virulent than those in Western Africa. Preben von Magnus discovered it in crab-eating macaque monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) used as study animals in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1958.5 The epidemic in the United States in 2003 was linked to prairie dogs infected by an imported Gambian pouched rat.6 The virus is highly prevalent in the tropical rainforests of Central and Western Africa. Before the epidemic in 2022, the UK had only documented seven cases of monkeypox, all of which had been imported from Africa or treated by healthcare workers. Three such occurrences occurred in 2018, followed by one in 2019, and three more in 2021. The last major monkeypox epidemic in a Western nation occurred which occurred in 2003 in the Midwest of the United States; however, this outbreak did not entail community transmission.7

Between May 13 and May 21, 2022, the WHO received reports of 92 confirmed and 28 suspected cases of monkeypox in 12 nonendemic countries.8 Most cases are in young men, who self-identified as MSM. There have been no deaths, and two hospitalizations for reasons other than isolation were reported worldwide. Scientists believe that monkeypox may have circulated at low levels in the UK or Europe for several years before to its emergence in the MSM community. Currently, research is being conducted to comprehend the introduction and fast spread of monkeypox in these countries.

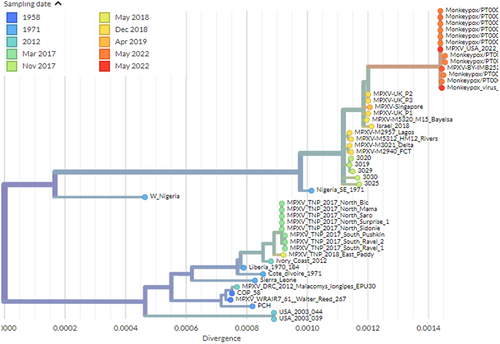

MPXV is a 197 kb linear DNA genome including 190 nonoverlapping ORFs >180 nt in length (1,7,26). The central coding region sequence (CRS) at MPXV nucleotide locations 56000–120000 is highly conserved and flanked by variable ends that include inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), like with other orthopoxviruses.9 The core region of the MPV genome encodes structural and essential enzymes and is like the variola virus by 96.3%. Despite this, the terminal regions of the MPV genome that encode virulence and host-range factors differ considerably. Comparing the genomes of MPV and smallpox virus demonstrates that MPV is a distinct species that evolved from an orthopoxvirus ancestor independently of variola virus.10 The 2022 monkeypox virus is most closely related to viruses associated with the exportation of monkeypox virus from Nigeria to several countries in 2018 and 2019, including the UK, Israel, and Singapore, according to a draft genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis shared by researchers from the National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge (INSA), Lisbon, Portugal.11 According to their preliminary findings, the outbreak virus differs by a mean of 50 SNPs from the 2018–2019 viruses, which is far more than one would expect given the estimated substitution rate for Orthopoxviruses. Gene loss events have already been observed in the context of endemic Monkeypox circulation in Central Africa, and they have been linked to human-to-human transmission. The microevolution scenario also implies that genome sequencing may provide sufficient resolution to track virus spread in the context of the current outbreak. The other recent draft genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis shared by Belgian researchers from the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp and the University of Antwerp in Antwerp indicates that the obtained genome belongs to the West African clade of MPXV and is most closely related to the recently uploaded genome from the outbreak in Portugal, providing further evidence of substantial community spread in Europe.12 Another draft monkeypox viral genome from Massachusetts, USA, confirms that the current epidemic outside of Europe is caused by viruses from the West African clade13 as shown in Figure 1. For all three genomes, molecular clock analyses assumed an evolutionary rate of 5 × 10−6 by following estimates of the variola virus from Firth et al.14 The growing number of cases from various countries has generated concerns about increased virus transmission from person to person.

3 TRANSMISSION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Monkeypox is a sylvatic zoonosis with human infections that is common in forest areas of Central and West Africa. It is caused by the monkeypox virus, which belongs to the orthopoxvirus family. Contact and droplet transmission by large, inhaled droplets to cause monkeypox15 The most common signs and symptoms of illness were rashes, fever, chills, adenopathy, headache, and myalgia.16 According to the WHO and CDC, there seems to be a greater number of individuals with groin rashes in the current epidemic. In rare situations, during the first stages of a disease, the rash has mostly appeared in the genital and perianal areas. In other instances, it has produced anal or genital lesions that resemble herpes, chickenpox, or syphilis.

Monkeypox's incubation period varies from 5 to 21 days but is usually between 6 and 13 days. The illness is often self-limiting, with symptoms generally disappearing on their own after 14–21 days.17 Lesions may be itchy or painful, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe (Table 1). Human monkeypox infection may be naturally acquired via a variety of channels (such as the respiratory system, skin, and mucous membrane) and from a variety of sources (e.g., rodents, humans, and nonhuman primates). Neither the relative contribution of the several probable sources of MPXV to naturally occurring human diseases nor the effect of the various routes of infection on clinical symptoms or disease development has been comprehensively studied. Several species of primates and rodents are known to be susceptible to infection with monkeypox virus. Because the types of animals that may become ill with monkeypox are currently unknown, all mammals should be considered susceptible as a precaution.18 Contact with both live and dead animals, as well as consumption of wild game or bush meat, are known risk factors.

| Characteristic | Monkeypox | Smallpox | Chickenpox |

|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||

| Recent contact with exotic animal | Yes | No | No |

| Recent exposure to a patient with vesicular rash | Possibleb | Yes | Yes |

| Time period | |||

| Incubation period | 7–17 d | 7–17 d | 10–21 d |

| Prodromal period | 1–4 d | 1–4 d | 0–2 d |

| Rash period (from the appearance of lesions to desquamation) | 14–28 d | 14–28 d | 10–21 d |

| Physical examination | |||

| Prodromal fever | Yes, often between 38.5°C and 40.5°C | Yes, often >40°C | Yes, up to 38.8°C |

| Malaise | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Headache | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lymphadenopathy | Yes | NO | NO |

| Distribution of skin lesions | Centrifugal (80%) or centripetal (5%) | Centrifugal | Centripetal |

| Depth of skin lesions | Superficial | Deep | Superficial |

| Evolution of skin lesions | Monomorphic (80%) or pleiomorphic (20%) | Monomorphic | Pleiomorphic |

| Desquamation (days after onset) | 22–24 | 14–21 | 6–14 |

| Lesions on palms and soles | Common | Common | Rare |

| Extracutaneous manifestations | |||

| Secondary skin/soft-tissue infection | 19% | Possible | Possible |

| Pneumonitis | 12% | Possible | 3–16% |

| Ocular complications | 4%–5% | 5%–9% | No |

| Encephalitis | <1% | <1% | <1% |

| Laboratory diagnosis | |||

| DNA detection (e.g., PCR) | MPV | Variola virus | VZV |

| Electron microscopy | Poxvirus particles | Poxvirus particles | Herpesvirus |

| Culture on chick chorioallantois | Characteristic pocks | Characteristic pocks | No growth |

| Serology | Orthopoxvirus and MPV antibodies | Orthopoxvirus and variola virus antibodies | Varicella antibodies |

- Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chaim reaction; VZV, varicella zoster virus.

- a Other diseases that can be confused with these infections include generalized vaccinia, disseminated infection with herpes zoster or herpes simplex virus, drug eruptions, enterovirus infections, dermatitis herpetiformis, rickettsialpox, and molluscum contagiosum.

- b Highest risk among household contacts, with a secondary attack rate of about 12%.

There are two clades of monkeypox virus: West African and Congo Basin (Central African). Although infection with the West African monkeypox virus may cause significant sickness, the disease is typically self-limiting. The case-fatality ratio for the West African clade has been estimated to be less than 1%, but it may surpass 10% for the Congo Basin clade.19 Children are more susceptible, and monkeypox exposure during pregnancy may result in difficulties, congenital monkeypox, or stillbirth.

The present epidemic has occurred first time in Europe when transmission networks have been found without apparent epidemiological ties to West or Central Africa. Furthermore, these are the world's first recorded instances of MSM. Monkeypox is transmitted to humans through close contact with an infected person or animal, or through contact with virus-contaminated material. The monkeypox virus spreads through close contact with lesions, bodily fluids, respiratory droplets, and contaminated materials such as bedding.20

The virus is most likely to transmit by intimate contacts, such as during sexual activity, given the relatively high frequency of human-to-human transmission observed in this event, as well as the possibility of community transmission without a history of travel to endemic regions. The likelihood of transmission without personal contact is regarded to be minimal. Before the 2022 epidemic, monkeypox was not considered a sexually transmitted disease. Nonetheless, the rapid spread of the virus between sexual partners during the early stages of outbreak has fueled concern that sexual contact might be another mechanism of transmission. Monkeypox generally has a mild clinical manifestation. In Nigeria, the West African clade, which has only been detected in European patients, has a case fatality rate of around 3.3%. However, the probability of instances with severe morbidity cannot be estimated with accuracy at this point. The risk is estimated as moderate for those with several sexual partners (including some MSM groups) and as low for the general population. According to the British HIV Association's (BHIVA) rapid statement issued May 17, 2022 on monkeypox virus, there is limited evidence as to how HIV impacts the risk of MPV acquisition or its disease course. Currently, BHIVA does not advocate any interventions for HIV-positive individuals beyond monitoring for clinical manifestations and exposure history. They propose that, for immunocompromised persons, the following are at greater risk and should get priority review: CD4 cell count <200 cells/mm3, recent HIV-associated disease (e.g., AIDS diagnosis in the prior 6 months), and Persistent HIV viraemia (e.g., >200 copies/ml).

According to a WHO statement issued on May 20, 2022—“Investigations ongoing into atypical cases of monkeypox now reported in eight countries in Europe”—the disease may be more severe in young children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals based on information from previous outbreaks. In the case of the most recent epidemic, we must wait for more epidemiological data to determine whether children or immunocompromised patients are susceptible to severe disease. Most patients recover in a few weeks.

4 DIAGNOSIS

Orthopoxvirus infections are usually detected by diagnostic testing (Table 1). Traditional methods like virus isolation from clinical specimens, electron microscopy, and immunohistochemistry are still useful, but they need a modern laboratory and a high level of technical knowledge.21 Orthopoxvirus and monkeypox virus may be detected in lesion samples using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). These tests can distinguish between viruses and their DNA. The real-time polymerase chain reaction is most successful in large facilities right now, which limits its usage in rural and low-resource settings. As technology advances, the PCR usage outside of large facilities may become possible.22

5 TREATMENT

Milder cases of monkeypox may go unreported and pose a danger of transmission from person to person. Because endemic illness is geographically restricted to portions of West and Central Africa, persons who travel and are exposed are likely to have minimal immunity to the infection. JYNNEOSTM™ (also known as Imvamune or Imvanex) has been approved in the United States for the prevention of monkeypox and smallpox.23 Because the virus that causes monkeypox and the virus that causes smallpox are so closely related, smallpox vaccination may also protect against monkeypox. According to African investigations, smallpox vaccination is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox. JYNNEOSTM™ was shown to be efficacious against monkeypox after animal studies and a clinical evaluation of its immunogenicity. Vaccination following exposure to monkeypox, according to experts, may also help prevent or reduce the severity of the disease. ACAM2000, which includes a live vaccinia virus, is approved for use in adults over the age of 18 who are at high risk of contracting smallpox.24 If administered under an extended access experimental new medication procedure, it may be used in patients who have been exposed to monkeypox. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises administering the vaccination within 4 days after exposure to prevent the beginning of the disease. Vaccination administered between 4 and 14 days after exposure may lessen disease symptoms but may not prevent the disease. Although smallpox vaccination previously provided protection against monkeypox, those younger than 40–50 years of age may be more susceptible to infection now, as smallpox vaccination campaigns were halted globally after the disease was eradicated in 1980. Individuals with close contacts of those infected with monkeypox, children, and immunocompromised individuals who have not received the smallpox vaccine in the last 3 years should consider vaccination based on the risk-benefit ratio. The vaccination will be more effective at protecting against the monkeypox virus the sooner it is administered. However, researchers studying monkeypox have identified several proteins on the virus to which macaque antibodies bind strongly, providing researchers working with newer vaccine technologies such as mRNA with some potential targets for monkeypox.

Cidofovir taken intravenously, Brincidavir and Tecovirimat administered orally are three of the most promising antiviral therapies for Orthopoxvirus species. The usefulness of Cidofovir and Brincidavir in treating human instances of monkeypox is unknown. Despite this, in vitro and animal investigations have shown that both are effective against poxviruses.25 According to studies involving numerous animal species, tecovirimat is beneficial for treating diseases caused by the orthopoxvirus. Human clinical trials revealed that the medicine is safe and well-tolerated, with just minor adverse effects.26 Monkeypox therapy should be improved to reduce symptoms, manage complications, and minimize long-term damage. Secondary bacterial infections should be treated according to the recommendations.

6 PREVENTION

To improve community awareness of the dangers of monkeypox transmission, community-based organizations and public health institutions/authorities should interact.27 According to the evidence now available, incidents have been discovered mostly, but not solely, among MSM. People with symptoms that resemble monkeypox should seek medical attention and refrain from sexual or other close contact activities until the virus has been ruled out or the disease has disappeared. However, since monitoring has been restricted, the degree of local transmission is unknown at this time.

For epidemic control, surveillance and early detection of new cases are crucial. Suspect incidents should be identified, tested, and reported as soon as possible. Positive patients should be isolated, and any affected mammalian pets should be tracked down.28 Close contacts at high risk should be vaccinated following a risk-benefit analysis if smallpox vaccinations are available in the country. If a recognized antiviral is available in the nation, severe cases may be treated with it. Most human infections have been transmitted from animal to human throughout time. Contact with wild animals, particularly those that are ill or dead, should be avoided at all costs, including their flesh, blood, and other body parts. All items containing animal flesh or components must also be thoroughly cooked before consumption. Any animals that may have come into touch with an infected animal should be confined, handled with care, and monitored for 30 days for monkeypox signs. Countries that are not endemic must prioritize the rapid detection, management, contact tracing, and reporting of new MPX cases. Countries should upgrade their contact tracing methods, their diagnostic capabilities for orthopoxviruses, and their vaccinations, antivirals, and personal protective equipment (PPE) for health workers.

7 CHALLENGES

Monkeypox has only been isolated in the wild once, from a Funisciurus squirrel in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, although it has the potential to infect a variety of mammalian species. Even though rodents seem to be a possible reservoir, the degree of viral circulation in animal populations and the virus's host species is unknown. Human monkeypox infections are difficult to track in endemic areas.29 Inadequate infrastructure, limited resources, faulty diagnostic tests and/or a lack of specimen collection, and clinical issues in identifying monkeypox disease all provide challenges to monitoring systems. It will be critical to explore the clinical aspects that identify monkeypox from other rash infections whenever further data from current monkeypox patients and earlier research initiatives become available. Even if current case definitions are sensitive and extensively used to identify rash infections, developing, and implementing a more specific case definition will improve the detection of confirmed monkeypox cases, simplify patient treatment, and limit human-to-human transmission. Healthcare workers must be trained regularly to maintain their knowledge, vigilance, and support for monkeypox monitoring. A larger network of laboratory-based monitoring will help us understand disease burden over time.

8 CONCLUSION

The increasing prevalence of human monkeypox occurrence needs additional investigation and analysis, as well as new research, to better understand the numerous elements that contribute to disease transmission and spread. There are various challenges with human disease, animal reservoirs, and the virus itself; an improved understanding of this lethal zoonosis can aid in the development of more effective preventive measures and the prevention of human infections. As a result, active disease monitoring should be employed to search for MPXV changes that are consistent with improving human adaptability. To ascertain the true geographic range of the disease, active surveillance should be maintained and expanded to any other sites where the virus is known or predicted to spread. Given the virus's apparent rapid spread, health workers in currently unaffected areas should be on high alert and ready to respond rapidly if suspected or confirmed cases in individuals are discovered. According to WHO, individuals most at risk are those who have had close personal contact with someone who has monkeypox, and this risk is not confined to MSM. This outbreak emphasizes the critical need for leaders to strengthen pandemic prevention, particularly the development of better community-led capacity and human rights infrastructure to support effective and non-stigmatizing outbreak responses. More incidents involving unknown transmission channels, possibly affecting additional communities, are expected to be reported in the future.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft preparation: Suresh Kumar. Writing—review and editing: Kalimuthu Karuppanan and Gunasekaran Subramaniam. Data curation and formal analysis: Suresh Kumar. Methodology, data curation, investigation, and validation: Suresh Kumar, Kalimuthu Karuppanan, Gunasekaran Subramaniam. Project administration, and supervision: Suresh Kumar.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the authors Selhorst et al., Isidro et al., and Gigante et al. for generating a draft genome of the monkeypox 2022 outbreak and submitting labs of genomic sequences and information for sharing their work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.