Clinical performance of Determine HBsAg 2 rapid test for Hepatitis B detection

Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is estimated to affect 292 million people worldwide, 90% of them are unaware of their HBV status. The Determine HBsAg 2 (Alere Medical Co, Ltd Chiba Japan [Now Abbott]) is a rapid test that meets European Union (EU) regulatory requirements for Hepatitis B surface antigen 2 (HBsAg) analytical sensitivity, detecting the 0.1 IU/mL World Health Organization (WHO) International HBsAg Standard. This prospective, multicentre study was conducted to establish its clinical performance. 351 evaluable subjects were enrolled, 145 HBsAg-positive. The fingerstick whole blood sensitivity and specificity were 97.2% and 98.5% (15′ reading, reference assay cut-off 0.05 IU/mL), sensitivity increasing to 97.9% with the prespecified cut-off 0.13 IU/mL (EU regulations). The venous whole blood, serum and plasma sensitivity was 97.2%, 97.9%, and 98.6%, respectively (15′ reading); reaching 99%, 99.5% and 100% specificity. A testing algorithm following up an initial positive fingerstick test result with plasma/serum test demonstrates 100% specificity. The Determine HBsAg 2 test gives 15-minute results with high sensitivity and specificity, making it an ideal tool for point-of-care testing, with the potential to enable large-scale population-wide screening to reach the WHO HBV diagnostic targets. The evaluated test improves the existing methods as most of the reviewed rapid tests do not meet the EU regulatory requirements of sensitivity.

Highlights

- Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a global health problem, and up to 90% of individuals infected with hepatitis B virus worldwide are unaware of their HBV status.

- Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) is the diagnostic marker used for detection of HBV infection, and is one of the first indicators of the disease.

- DetermineTM HBsAg 2 test is a rapid test providing an HBsAg result in 15 minutes with high sensitivity and specificity. The test meets the EU regulatory requirement for analytical sensitivity for HBsAg tests of 0.13 IU/mL, and is well placed to support the WHO diagnostic target, to diagnose 90% of HBV infected people by 2030.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a communicable disease, which affects approximately 292 million people worldwide, including an estimated 4.7 million infected people (0.9% of the population) in the EU (European Union)/EEA. HBV is 50 to 100 times more infectious than human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and the development of chronic hepatitis B (CHB), defined as Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity for 6 months or longer, is a risk factor for serious liver diseases, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.1-4 As CHB infection may be asymptomatic, and screening programs are not widely implemented, a diagnosis of CHB is often obtained when late-stage symptoms appear. Approximately two-thirds of CHB infected patients in Europe are unaware of their HBV status.5-9 Published estimates show that 96000 people die each year in EU/EEA countries from HBV and hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related liver disease.10, 11

The Global Health Sector Strategy to eliminate viral hepatitis by 2030, approved by the 69th World Health Assembly in 2016, includes the diagnosis of 90% of HBV infected people by 2030. It was estimated in 2016 that only 10% of 292 million HBV infected individuals were diagnosed. Hence a significant increase in HBV screening programs is required. The emergence of directly acting antivirals for the treatment of HCV has increased the emphasis on screen and treatment programs to meet World Health Organization (WHO) targets12; thus parallel screening of HBV could conveniently be incorporated into these new programs.

HBsAg is the outer coat of HBV, which is produced in excess during the course of infection and can be detected easily in blood. HBsAg, together with HBV DNA, is the earliest indicator of acute infection and may be present before symptoms appear. It is also present in patients with chronic infection and is used to screen for and detect hepatitis B at different stages of the disease.13, 14 Identification of infected individuals and initiating treatment in a timely manner, before progression to significant liver disease, is imperative for maximizing treatment efficacy.5, 15

Currently, HBV screening in Europe is largely restricted to laboratory testing. However, rapid tests present several advantages for patient screening, such as easily obtainable results, testing convenience, the potential to facilitate the diagnosis earlier in the disease stage as well as to conduct testing outside established healthcare settings and to reach high-risk groups.6, 16-22

The Determine HBsAg 2 (Alere Medical Co, Ltd Chiba Japan [Now Abbott]) is a recently developed rapid test which uses 50µL plasma, serum or whole blood (venous or fingerstick) for detection of HBsAg, producing a result in 15 minutes. The test is intended as an aid to detect HBsAg in HBV infected individuals.

This prospective study was conducted with the primary objective to establish the clinical test performance (sensitivity and specificity) of the Determine HBsAg 2 test in serum, plasma and whole blood samples collected by venipuncture (all sample types) and fingerstick (whole blood only). The Abbott Architect quantitative HBsAg assay (“Architect”), with the cut-off 0.05 IU/mL, was used as the primary reference method. Prespecified analyses were also conducted using the cut-off 0.13 IU/mL, which is the requirement for analytical sensitivity for an HBsAg test in the EU.23

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design

This study was conducted at multiple study sites in Europe. The applicable Ethics Committee for each participating site approved of the study and all subjects provided written informed consent.

The intended population included individuals of all ages who presented to participating clinical sites for HBsAg screening (high-risk population) or for routine follow-up of confirmed HBV, as well as relevant control populations, including Hepatitis A-, Hepatitis C-, and HIV-positive patients. Subjects who had already participated in this study at a previous date, or who were enrolled in a study evaluating an investigational drug and had started taking this drug (ie, had progressed past the screening stage), or who belonged to a vulnerable population as deemed inappropriate for the study by the study investigator(s), were not eligible for study enrolment.

The subjects provided one ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) whole blood tube, one tube for Serum separator tubes (SST) obtained by venipuncture, and a fingerstick blood sample. The fingerstick blood sample was obtained using an EDTA capillary blood collection tube (n = 223) or a Microsafe capillary blood collection tube (SAFE-TEC Clinical Products LLC, PA) (n = 125). After an aliquot of the EDTA whole blood venipuncture sample had been removed for Determine HBsAg 2 testing, the tube was centrifuged to obtain a plasma specimen. Each sample type was evaluated using Determine HBsAg 2, and each sample type of each patient was measured once only. Fingerstick testing was conducted by nonlaboratory study staff members such as nurses and doctors; venous whole blood, plasma, and serum testing were conducted by nonlaboratory or laboratory study staff members according to local protocol. All testing personnel were blinded to the subject's clinical HBV status. To ensure blinding between sample types, each study staff member tested only one sample type from each subject during each testing occasion, except during batch testing sessions, where the samples were coded. Serum and plasma samples were frozen and batch-tested. A Determine HBsAg 2 test result is intended to be interpreted between 15 and 30 minutes after sample application, and to validate this time interval in this study every Determine HBsAg 2 test was interpreted at 15 minutes, and again at 30 minutes by the same operator. The Abbott ARCHITECT quantitative HBsAg assay (“Architect”), with the cut-off 0.05 IU/mL, was used as the primary reference method. In the EU, an analytical sensitivity of 0.13 IU/mL is required for an HBsAg diagnostic test.23 Hence prespecified statistical analyses were also conducted using the cut-off 0.13 IU/mL. For the resolution of discrepancies and disease reclassification (see reference methods) testing was also performed using the Elecsys HBsAg II assay and Elecsys HBV core antibody testing. Basic demographic information and a brief medical history were collected from each subject. Results from the sites' standard of care HBV diagnostic testing were also recorded.

2.2 Investigational Determine HBsAg 2 test

The Determine HBsAg 2 test is an in vitro, visually read, qualitative, immunochromatographic assay for the detection of HBsAg in human serum, plasma, fingerstick whole blood or venous whole blood.

The Determine HBsAg 2 test consists of single-use test strips and a chase buffer bottle, both stored at room temperature and requires no maintenance. The assay requires 50 µL specimen for a test, and the test result can be interpreted at 15 minutes and no later than at 30 minutes. Details of the test can be found in the package insert.24

2.3 Study reference methods

The reference method for the study, the Abbott ARCHITECT quantitative HBsAg assay, uses a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay and was conducted using the Architect i2000 analyzer (Abbott Diagnostics, IL). A positive result was automatically repeated. For a subset of the subjects who were positive on Architect (above 0.05 IU/mL) without an existing diagnosis of HBV, further testing for potential disease reclassification from HBV disease positive to HBV disease negative was conducted with the Elecsys HBsAg II assay, and with the Elecsys II confirmatory assay where applicable. This testing was performed using the MODULAR E170 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), which uses an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay, and was also conducted for subjects with two or more sample types that showed discrepant results between the Determine HBsAg 2 test and Architect. As part of disease reclassification and discrepant result resolution, total HBV core antibody (immunoglobulin G + immunoglobulin M) analysis using the MODULAR E170 platform was also conducted. EDTA plasma or serum from each subject was used for the reference testing. The assays were conducted according to the manufacturers' instructions.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study population

This study enrolled 365 subjects across five clinical sites in the UK and one clinical site in Spain. In the UK, two sites recruited patients at hepatology clinics, one site recruited patients at a gastroenterology clinic, one at a digestive diseases clinic and a paediatric hepatology clinic, and one at a sexual health clinic. The clinical site in Spain was affiliated with five recruiting hospitals, of which four recruited patients at digestive disease clinics and one at an infectious disease clinic. Eleven subjects had no reference result available or improper sample handling and were excluded from the analyses.

The median age of all evaluable subjects was 49 years (range: 2 to 86 years). Eight children or adolescents (age <18 years) were enrolled into the study. One hundred sixty-three (46.4%) evaluable subjects were female.

Fifty-five patients in the study had Hepatitis A, Hepatitis C, and/or HIV. Sixteen patients had auto-immune liver disease, and 29 additional subjects had undergone liver transplant or had another liver disease, excluding HBV. There were seven pregnant subjects in the study. In total, 90 HBsAg-negative subjects and 12 HBsAg-positive subjects had one of these coexisting conditions. In addition, 16 subjects had evidence of past Hepatitis A infection documented in their medical records and 25 subjects had documented past Hepatitis C.

Subjects without an existing diagnosis of HBV who were positive by the Architect quantitative HBsAg assay were further tested for potential disease reclassification. There were eight subjects with a low positive result on the Abbott Architect assay and no prior clinical diagnosis. Four of these subjects (HBsAg results: 0.1-1.16 IU/mL) had a nonreactive result by Elecsys HBsAg II and nonreactive result for HBV core antibody and were classified as disease negative. Three subjects (HBsAg results: 0.07-0.15 IU/mL) had a nonreactive result by Elecsys HBsAg II and a reactive HBV core antibody result, indicating the possibility of an undetected HBV infection, a past undiagnosed HBV infection or occult Hepatitis B.25-27 These three subjects were classified as indeterminate and were excluded from the study analyses. One of the eight subjects (HBsAg result: 0.14 IU/mL) had a reactive result on the Elecsys II HBsAg test as well as on the Elecsys confirmatory neutralization test and the HBV core antibody test, and was maintained as disease positive in the study analysis.

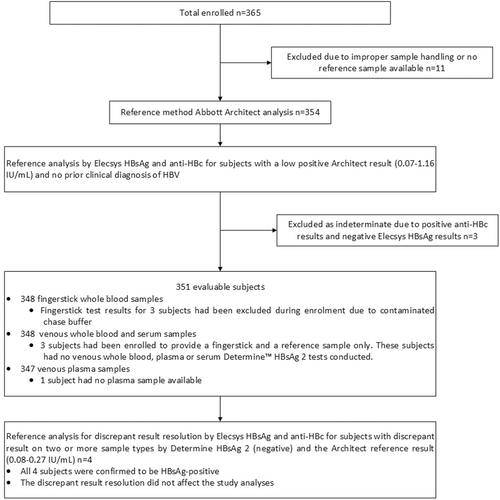

In total, 351 subjects were evaluable, 344 with all sample types. The subject enrolment is described in the flowchart in Figure 1. Three patients had their fingerstick test result excluded due to contaminated chase buffer, and three additional patients were recruited to provide fingerstick samples only to provide the required subject numbers for each sample type. One subject had no plasma sample available. Thus, available samples were: 348 fingerstick whole blood samples, 348 venous whole blood samples, 347 plasmas and 348 sera. From the total, 145 were HBsAg-positive subjects and 206 HBsAg-negative subjects, with patient characteristics are illustrated in Table 1. Of the 206 HBsAg-negative subjects, 203 Determine HBsAg 2 test results were evaluable in fingerstick whole blood, venous whole blood, and serum, and 202 Determine HBsAg 2 test results were evaluable in plasma; all 145 HBsAg-positive subjects had evaluable Determine HBsAg 2 test results for each of the four sample types.

| Descriptive statistics | All (N = 351) | HBsAg-positive patients (N = 145) | HBsAg-negative patients (N = 206) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 49 (15.1) | 46 (14.1) | 51 (15.5) |

| Min-max | 2, 86 | 7, 76 | 2, 86 |

| Gender | |||

| F | 163 (46.4%) | 62 (42.8%) | 101 (49.0%) |

| M | 188 (53.6%) | 83 (57.2%) | 105 (51.0%) |

| Acute Hepatitis B | 8 (2.3%) | 8 (5.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Main conditions, excluding Hepatitis B | |||

| Hepatitis A | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Hepatitis C | 24 (6.8%) | 1 (0.7%) | 23 (11.2%) |

| HIV | 32 (9.1%) | 2 (1.4%) | 30 (14.6%) |

| Auto-immune liver disease | 16 (4.6%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (7.8%) |

| Other liver diseases* | 29 (8.3%) | 2 (1.4%) | 27 (13.1%) |

| Pregnancy | 7 (2.0%) | 6 (4.1%) | 1 (0.5%) |

- Note: In addition, 25 subjects (7.1%) had past Hepatitis C and 16 subjects (4.6%) past Hepatitis A, based on their medical records.

- Abbreviations: F, female; M, male SD, standard deviation.

- * Including liver transplant.

The subjects' clinical HBV status was based on a documented HBV infection in their medical records. Where relevant, standard of care HBsAg testing for study participants had been conducted before study enrolment. With one exception, the HBsAg-positive patients in the study, based on all the reference testing, had a documented HBV diagnosis from the past in their records. Eight subjects had a recent HBV diagnosis (within the last 6 months). The study staff conducting Determine HBsAg testing remained blinded to the subject's HBsAg standard of care results.

3.2 Determine HBsAg test results

A summary of results is shown in Table 2 (all sample type results). With test readings at 15minutes, using the Architect cut-off of 0.05 IU/mL, the Determine HBsAg 2 results obtained were the following: Determine HBsAg 2 with fingerstick whole blood had a sensitivity of 97.2% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 93.1, 99.2), and a specificity of 98.5% (95.7, 99.7). With venous whole blood, Determine HBsAg 2 had a sensitivity of 97.2% (93.1, 99.2) and a specificity of 99.0% (96.5, 99.9). In venous plasma samples, Determine HBsAg 2 had a sensitivity of 98.6% (95.1, 99.8) and a specificity of 100.0% (98.2, 100.0). When using the venous serum, the Determine HBsAg 2 sensitivity was 97.9% (94.1, 99.6) and the specificity was 99.5% (97.3, 100.0).

| aRead time | TP | FN | TN | FP | Total | % Sens (95% CI) | % Spec (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fingerstick whole blood | |||||||

| 15min | 141 | 4 | 200 | 3 | 348 | 97.2 (93.1, 99.2) | 98.5 (95.7, 99.7) |

| 30min | 141 | 4 | 200 | 3 | 348 | 97.2 (93.1, 99.2) | 98.5 (95.7, 99.7) |

| Venous whole blood | |||||||

| 15min | 141 | 4 | 201 | 2 | 348 | 97.2 (93.1, 99.2) | 99.0 (96.5, 99.9) |

| 30min | 141 | 4 | 200 | 3 | 348 | 97.2 (93.1, 99.2) | 98.5 (95.7, 99.7) |

| Plasma | |||||||

| 15min | 143 | 2 | 202 | 0 | 347 | 98.6 (95.1, 99.8) | 100.0 (98.2, 100.0) |

| 30min | 145 | 0 | 202 | 0 | 347 | 100.0 (97.5, 100.0) | 100.0 (98.2, 100.0) |

| Serum | |||||||

| 15min | 142 | 3 | 202 | 1 | 348 | 97.9 (94.1, 99.6) | 99.5 (97.3, 100.0) |

| 30min | 145 | 0 | 202 | 1 | 348 | 100.0 (97.5, 100.0) | 99.5 (97.3, 100.0) |

| Fisher's P value | .1433 | .3666 | |||||

- Note: When using the cut-off 0.13 IU/mL, the Determine TM HBsAg 2 sensitivity increases to 97.9% at 15 and 30minutes for fingerstick and venous whole blood samples, and to 99.3% and 98.6% at 15minutes for plasma and serum samples, respectively.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

Test readings were also recorded at 30minutes (Table 2). The sensitivity with fingerstick whole blood was 97.2% (95% CI: 93.1, 99.2); the specificity was 98.5% (95.7, 99.7). The sensitivity with venous whole blood was 97.2% (93.1, 99.2) and the specificity was 98.5% (95.7, 99.7). In plasma samples the sensitivity was 100.0% (97.5, 100.0) and the specificity was 100.0% (98.2, 100.0). The Determine HBsAg 2 sensitivity with serum was 100.0% (97.5, 100.0) and the specificity was 99.5% (97.3, 100.0).

A Fisher's exact test was performed among the eight categories consisting of sample types and reading times. There was no statistically significant difference among the eight categories for either sensitivity or specificity as the P values were more than .05 (Table 2).

When using the cut-off 0.13 IU/mL, which is the analytical sensitivity required for an HBsAg diagnostic test in the EU,23 the Determine HBsAg 2 sensitivity at 15 and at 30 minutes for fingerstick and venous whole blood samples increased to 97.9% (95% CI: 94.0, 99.6). With this cut-off, the Determine HBsAg 2 sensitivity at 15 minutes increased for plasma samples to 99.3% (96.2, 100.0) and for serum samples to 98.6% (95.1, 99.8). In the study, one sample had a concentration of 0.08 IU/mL, which is higher than the reference method cut-off 0.05 IU/mL, but lower than then EU required analytical sensitivity of 0.13 IU/mL. For this sample, the Determine HBsAg 2 plasma and serum results were positive based on the 30-minute readings, but negative based on the 15-minute readings, and the Determine HBsAg 2 fingerstick and venous whole blood results were negative at both time points.

To increase the diagnostic specificity, the Determine HBsAg 2 performance for fingerstick and venous whole blood was also calculated using an algorithm where a positive Determine HBsAg 2 fingerstick or venous whole blood test result is followed up with a Determine HBsAg 2 test using plasma or serum to confirm results (Table 3). This algorithm resulted in 100% specificity. The fingerstick results with quantitative values are illustrated in Table 4.

| Read time | TP | FN | TN | FP | Total | % Sens (95% CI) | % Spec (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fingerstick whole blood | |||||||

| 15min | 141 | 4 | 203 | 0 | 348 | 97.2 (93.1, 99.2) | 100.0 (98.2, 100.0) |

| 30min | 141 | 4 | 203 | 0 | 348 | 97.2 (93.1, 99.2) | 100.0 (98.2, 100.0) |

| Venous whole blood | |||||||

| 15min | 141 | 4 | 203 | 0 | 348 | 97.2 (93.1, 99.2) | 100.0 (98.2, 100.0) |

| 30min | 141 | 4 | 203 | 0 | 348 | 97.2 (93.1, 99.2) | 100.0 (98.2, 100.0) |

- Note: When using the cut-off 0.13 IU/mL, the Determine HBsAg 2 sensitivity at 15 and 30 minutes for fingerstick and venous whole blood samples is 97.9%.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

| Determine HBsAg 2 fingerstick test result | n | Architect HBsAg, IU/mL |

|---|---|---|

| TN | 200 | <0.05-1.16a |

| FN | 4b | 0.08-0.27 |

| FP | 3 | <0.05 |

| TP | 141 | 1.5-124925 |

| Total | 348 |

- Note: The total number of samples in each group, as well as the HBsAg concentration ranges, are shown.

- Abbreviations: FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

- a Four subjects with Architect values between 0.01 and 1.16 IU/mL were reclassified as HBV negative through additional testing, as described in reference methods.

- b All four FN were positive with the serum and plasma tests based on the 30-minute reading. Two plasma and one serum test results were positive based on the 15-minute reading.

For the eight HBsAg-positive recently diagnosed HBV study subjects, and the eight subjects aged 17 or less (including three subjects younger than 10 years old and three HBsAg-positive subjects), all Determine HBsAg 2 results were correct.

There was no observable difference in the performance of the Determine HBsAg 2 between the fingerstick sampling by a Microsafe capillary tube (n = 125) and an EDTA capillary tube (n = 223). There were two false-positive fingerstick results (at 15 minutes and at 30 minutes each) with the EDTA capillary tube and one false positive fingerstick result (at 15 minutes at 30 minutes) with the Microsafe capillary tube. Using the cut-off 0.13 IU/mL, there were two false-negative fingerstick results (at 15 minutes and at 30 minutes each) with the Microsafe capillary tube and one false-negative fingerstick result (at 15 minutes and at 30 minutes) with the EDTA capillary tube.

The Determine HBsAg 2 test results for the eight subjects eligible for reclassification are as follows: The four subjects that were reclassified as disease negative had Determine HBsAg 2 results that were negative on all sample types at all time points. The one subject classified as disease positive had mixed results on the Determine HBsAg 2; all sample types at 15 minutes were negative, fingerstick and venous whole blood at 30 minutes were negative, and plasma and serum at 30 minutes were positive. The three subjects that were indeterminate had Determine HBsAg 2 results that were negative on all sample types at all time points.

Further discrepant result resolution investigation was conducted for four subjects who had discrepancies between two or more sample types on Determine HBsAg 2 (negative results) and the Architect reference result. Three of these four subjects were known to have chronic HBV and had a low positive result on Architect (0.08-0.27 IU/mL); the fourth subject had an Architect result of 0.14 IU/mL and no previous HBV diagnosis. The fourth subject was investigated for disease reclassification as described above and was kept as disease positive. All four subjects were confirmed positive on the Elecsys HBsAg II assay, and three of the four subjects were also confirmed positive on the Elecsys HBsAg confirmatory test and the HBV core antibody test, whereas there was an insufficient sample for further testing of the fourth subject. The discrepant result resolution results did not affect the study analyses. Notably, one of these four subjects had a previous diagnosis of HIV.

4 DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates successful HBV near-patient testing by the Determine HBsAg 2 test, which meets the EU regulatory requirements for analytical sensitivity and could detect a concentration of 0.1 IU/mL HBsAg28 or even less, 0.03 IU/mL, of HBsAg by testing the WHO International Standard.29 In this prospective study, the fingerstick and venous whole blood diagnostic sensitivity reached 97.9% at 15 and 30 minutes, and 100% for serum and plasma at 30 minutes. Only three samples with concentrations of 0.14 to 0.27 IU/mL showed false-negative Determine HBsAg 2 test results using whole blood. The complexity of the whole blood matrix in comparison with plasma or serum may account for the differences between the sample types in the observed results.

The Determine HBsAg 2 fingerstick test has the potential to yield a rapid and reliable diagnosis at the point-of-care (specificity of 98.5% at 15 and 30 minutes) so that patients with HBV can be appropriately referred to specialist clinics for more detailed disease stratification and treatment where indicated. If confirmed by the Determine HBsAg 2 test using plasma or serum, the specificity increases to 100%.

In the study setting, testing was successfully conducted in hospitals outside laboratories. As demonstrated in the study, the whole blood testing does not require laboratory personnel or equipment, making it suitable for incorporation into the physician office workflow. This emphasizes the potential utility of The Determine HBsAg 2 test to broaden access to screening by bringing the test closer to the subject and away from the confines of clinical and laboratory settings.

Although HBsAg rapid tests are successfully used in developing countries, only a few rapid tests have been approved for use in the EU, as most of the rapid tests do not meet the European regulatory requirement for the analytical sensitivity.23, 30-33 A recent meta-analysis of 49 HBsAg rapid tests found that the analytical sensitivity of most tests was around 4 IU/mL, whereas the claim by most manufacturers was less than 0.5 IU/mL.30 WHO data from their performance evaluations showed that the analytical sensitivity of most rapid tests is in the range of 2 to 10 IU/mL,34 and currently no rapid test included in a recent review has a reported analytical sensitivity of 0.13 IU/mL.33 An analytical sensitivity of more than 1 IU/mL is reported to reduce the reliability of a test to detect asymptomatic HBV infections.30 Notably, false-negative HBsAg rapid test results have been reported with low HBsAg concentrations and viral load, specific genotypes and HBsAg mutants.30, 32, 35

A recent meta-analysis of other HBsAg rapid tests in 30 studies performed between 1996 and 2015 showed an overall pooled sensitivity of 90.0% and a pooled specificity of 99.5%. Most individual HBsAg studies that reported a sensitivity more than 90% in this meta-analysis were conducted in a laboratory setting rather than in a field setting with testing at the point of care, as was done in this report for fingerstick testing, or had a limited number of HBsAg-positive patients (n ≤ 25).33 One study published in 2013, including 3956 subjects in a French general population of whom 85 were HBsAg-positive, reported a sensitivity of 96.5% for Vikia HBsAg, 93.6% for Determine HBsAg (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL; this test is the previous generation of the test evaluated in this report) and 90.5% for Quick Profile (Lumiquick, Santa Clara, CA). This study evaluated venous whole blood samples rather than fingerstick samples.32

Other recent studies have reported sensitivities for HBsAg rapid test of 92.3% to 100%7, 36-41; these studies were conducted in laboratory settings using only serum or plasma samples36, 37, 40, 41 and/or had a limited number of HBsAg-positive subjects (n ≤ 14).7, 38, 39 A sensitivity of 95.2% in fingerstick or venous whole blood samples for an HBsAg test (All Test Biotech Hangzhou China) used at the point of care was reported in a Malaysian study including 295 subjects, of whom 145 were HBsAg-positive.42 The limitations of the current study are the relatively low numbers of recently diagnosed Hepatitis B patients as well as the low number of children tested. However, the strong performance of the Determine HBsAg 2 test merits further investigation in community settings and in studies evaluating patient outcomes based on the incorporation of the test into clinical practice. Furthermore, in the current era of HCV cure and the WHO targets to eliminate viral hepatitis by 2030, there will be a major emphasis on screening and diagnosis of viral hepatitis to meet these challenges. The opportunity to screen for HBV in tandem with HCV, as we scale up public health approaches including test and treat strategies, should not be missed. Point-of-care tests will be an essential tool in the drive to increase testing and diagnosis rates, but it is imperative that the test is robust with high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. The findings of this study make the case for the Determine HBsAg 2 test to facilitate the large increase in population-wide testing, required in most countries, to reach the targets of 90% diagnosed and 80% of eligible patients treated by 2030.1 The performance of the Determine HBsAg 2 test with a readily available result, obtained in 15 minutes, underlines its potential critical role in HBV diagnosis and management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to acknowledge William Tong (RIP) for his prior review and critical comment of the manuscript. The Spanish authors want to acknowledge the following collaborators: Noelia Reyes, Lucia Morago, Sandra Arroyo, Ana Molina, Laura Broto, Silvia Barturen, Paula Doust, Nuria Dominguez, María Ortiz, Yolanda Sanchez, Almudena Acebes, Lourdes Ferreira, Elena Saez, Diana Carrillo, Fernando Cava, Victorino Diez, Jesus Troya Garcia, Guillermo Cuevas Tascón, Javier Solis Villa. This work was supported by Abbott Diagnostics Medical Co., Ltd. Chiba Japan (now Abbott), who provided the funding for the study as the study sponsor.