Direct-acting antiviral agents in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C—Real-life experience from clinical practices in Pakistan

Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the clinical effectiveness in terms of sustained virological response (SVR), predictors of SVR and safety of available second-generation generic direct-acting antivirals in Pakistani chronic hepatitis C patients. This is a retrospective study conducted in multiple centers of Pakistan from January 2015 to January 2019. The samples include patients infected with chronic hepatitis C virus, regardless of virus genotype, cirrhosis, or prior treatment. A total of 993 patients were included in the present study, with the majority receiving sofosbuvir with daclatasvir (95%), sofosbuvir with daclatasvir and ribavirin (4%), and sofosbuvir with ribavirin (1%). There were 96% cases of chronic hepatitis, 3% cases compensated cirrhosis, and 1% cases of decompensated cirrhosis. Genotype 3 (99.6%) was the most common genotype. Overall SVR after 12 weeks was 98% for all treatment regimens. High SVR12 was observed with sofosbuvir in combination with daclatasvir (98.5%), then sofosbuvir in combination with daclatasvir and ribavirin (90.2%) and sofosbuvir in combination with ribavirin (75%). SVR rates were high in chronic hepatitis C patients (98.2%) as compared with cirrhotic patients (92.1%) and it was high in treatment-naive (98.8%) then interferon experienced patients (90.1%). In multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, patients’ education status, treatment strategy, viral load, and alanine aminotransferase had a statistically significant association with SVR at 12 weeks. No major adverse events occurred which required treatment discontinuation. Generic oral direct acting antiviralss (sofosbuvir with daclatasvir) achieved higher SVR12 rates and were well tolerated in this large real-world cohort of genotype 3 infected patients.

Highlights

-

In this study we have analyzed the clinical effectiveness, predictors and safety profile of available second generation generic direct-acting antivirals in Pakistani chronic Hepatitis C patients.

-

Generic sofosbuvir with daclatasvir achieved 98% SVR rate after 12 weeks in this large real-world cohort of genotype 3 infected patients.

-

The predictors of low SVR12 were poor education status, high viral load and elevated level of ALT.

Abbreviations

-

- ALP

-

- alkaline phosphatase

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- AST

-

- aspartate aminotransferase

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CKD

-

- chronic kidney disease

-

- DAA

-

- direct acting antivirals

-

- DCV

-

- daclatasvir

-

- DM

-

- diabetes mellitus

-

- ETR

-

- end-of-treatment response

-

- HB

-

- hemoglobin

-

- HBV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- HIV

-

- human immunodeficiency virus

-

- HTN

-

- hypertension

-

- IFN

-

- interferon

-

- IHD

-

- ischemic heart disease

-

- PLT

-

- platelets

-

- RBV

-

- ribavirin

-

- RVR

-

- rapid virological response

-

- SOF

-

- sofosbuvir

-

- SVR

-

- sustained virological response

-

- TBR

-

- total bilirubin

-

- WBCs

-

- white blood cells

1 INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the main cause of liver pathologies and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) worldwide.1 Globally, 71 million people infected with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) infection, with an estimated 3.5 to 5 million death annually.2 According to recent estimates, Pakistan has the second-largest HCV burden in the world, with 4.5% to 8.2% HCV seroprevalence.3, 4 Out of the seven major HCV genotypes,5 the majority of HCV infections in Pakistan are GT3a (69.1%), followed by GT1 (7.1%), GT2 (4.2%), and GT4 (2.2%).4, 6 In Pakistan, HCV is transmitted by many risk factors, such as health care practices, that is injections and blood transfusion in health care professionals (27%-42.3%) and in the general population (7.8%-68%), community-based activities, that is ear and nose piercing, barbering, and injecting drug use.4, 7, 8

Before the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), the HCV treatment was interferon (IFN)-based that had many side effects, that is poorly tolerated and low sustained virological response (SVR) rate (50%).9 In spite of “Chief Minister's Program for Hepatitis B and C Control in Pakistan,” the IFN-based treatment was only effective in 67% to 74% of the infected population.10, 11

Hepatitis C treatment has been transformed by the development of DAAs. HCV replication cycle is inhibited by these drugs mainly interfering with the activity of nonstructural proteins of HCV.12 Three drug classes (inhibitors of the NS3/NS4A protease, inhibitors of the NS5A complex, and inhibitors of the NS5B polymerase) have been developed and approved by the FDA. Combinations of two or more drugs from three classes achieve high (>90%) SVR rates and are well tolerated.12

In Pakistan, the treatment for CHC infection is changing to the new DAAs. Since November 2014, sofosbuvir and ribavirin were the registered and widely available DAAs in Pakistan.13, 14 Sofosbuvir (SOF) inhibits the NS5B region of HCV which encodes RNA-dependent RNA polymerase enzyme for viral replication. SOF has pangenotypic action with less side effects as compared with IFN-based therapy.15 Pakistan is among the high-burden countries for HCV where the majority of the HCV-infected population fall in the lower-income category. They are unable to buy high priced branded SOF for their treatment. Therefore, the government of Pakistan and the pharmaceutical companies started manufacturing SOF generics at low prices to control the HCV prevalence.16

The inclusion of SOF-based DAAs in the “National Guidelines for HCV Treatment in Pakistan” has increased its use by clinicians. Recently, daclatasvir (DCV; HCV NS5A replication complex inhibitor) the new DAAs are also available in Pakistan and added in the national treatment program with a combination of SOF against GT3. Such additions will certainly offer a better safety profile with improving patient compliance to treatment.15, 17

However, these DAAs are designed on the basis of the structure of the protein of GT1HCV. Also, the registration trials for these drugs contained few patients infected with GT3HCV, which is highly prevalent in Pakistan. This raises a concern about the effectiveness of these drugs on Pakistani patients. Given the limited data on treatment of chronic GT3 HCV infection with DAAs and the above concerns, this study was conducted to gather data on the antiviral efficacy of generic DAAs with respect to treatment outcome in chronic HCV Pakistani patients. The predictors of SVR at 12 weeks and the safety profile of DAAs were also determined in this cohort.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study population

This was a retrospective cohort study of 1200 CHC patients, who were treated with different sofosbuvir-based DAAs between January 2015 and January 2019. The patient records were collected from Centre for Liver and Digestive Diseases, Holy family Hospital, Rawalpindi and outdoor patient department of General Teaching Hospital, Islamabad. Both hospitals are tertiary care hospitals. Out of 1200 patients, 993 patients completed the therapy while 207 patients were lost of follow-ups and missing data. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Holy Family Hospital, Institute of Biomedical and Genetic Engineering and National University of Science and Technology.

2.2 Medications

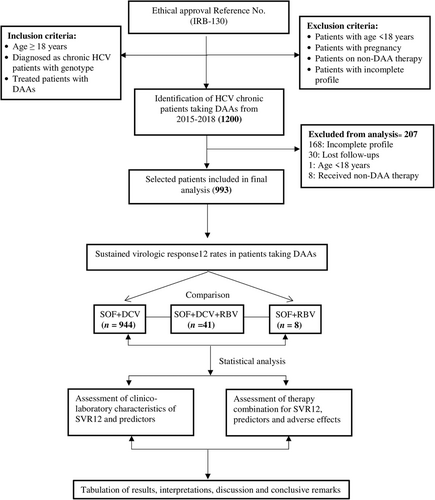

Treatment and management of patients at study centers were as per the national guidelines. Generic SOF was given in a dose of 400 mg/day, DCV in a dose of 60 mg/day, both in a single daily dose and patients were advised to take them after breakfast for 12 weeks. Ribavirin 1000 mg (in patients < 75 kg) or 1200 mg (in patients >75 kg) was added to the regimen (Figure 1).

2.3 Endpoint

Treatment response was assessed with HCV RNA viral load (IU/mL) at 4 weeks after initiation of treatment (RVR; defined as undetectable HCV RNA after 4 weeks of therapy), at the end of treatment (EOT; defined as undetectable HCV RNA at treatment completion), and 12 weeks after completion of treatment (SVR12; defined as undetectable viral load at 12 weeks after the end of treatment). Tests were performed using Artus HCV RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen) or Hepatitis C Viral RNA Quantitative/Qualitative Fluorescence Diagnostic Kit (PCR Fluorescence Probing) by Sansure Biotech. The lower limit of detection of HCV RNA was 34 IU/mL for Artus HCV RT-PCR Kit and 50 IU/mL for Sansure Biotech Kit. Patients that completed the therapy but did not had any SVR results (ie, missing data or lost to follow up) were excluded from the analysis.

2.4 Safety assessments

All patients were included in the safety assessment. Laboratory tests for assessments of biochemical and hematological parameters, and safety assessments were recommended at baseline, treatment at week 4, EOT (week 12) and posttreatment week 12.

2.5 Demographics data

Data about the following variables were obtained from all patients included in the analyses.

Age, gender, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, residence, socioeconomic status, education, marital status, employment, race, previous treatment status (naıve or experienced) and if treatment experienced, details about previously administered medications.

2.6 Clinical data

Data were collected at baseline including blood count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), bilirubin, HBsAg, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and HCV-RNA. For the determination of cirrhosis status, data from abdominal ultrasonography reports included echo pattern of the liver, the presence of hepatic focal lesions, ascites, splenomegaly or any other comorbidities like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and ischemic heart disease records were included. Pretreatment PCR ≥ 80 000 IU/mL was considered as high viral load whereas PCR < 80 000 IU/mL was considered as low viral load.18

2.7 Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 was used for the analysis of the data. One-way analysis of variance was used for the calculation of means and standard deviations of continuous variables. Categorical data is presented in the form of frequencies and percentages. For observing the significance between categorical variables, we used a χ2 test. Relevant variables with a P value <.25 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis.19 For obtaining a final model, multivariate logistic regression analysis with the Wald statistical criteria was considered and used. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlations assessed among those variables which were included in multivariate analysis. The results of multivariate analysis were presented as P value, adjusted odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval (CI). The fit of the model was assessed by Hosmer Lemeshow and overall classification percentage.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of patients at baseline

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients at baseline are shown in Table 1. Mean age of the cohort was 45.6 ranging from 18 to 90 years with females in majority than males (55%). Comorbidities at baseline included diabetes (26.1%), hypertension (11.5%), chronic kidney disease (6.3%), ischemic heart disease (4.3%), HIV (0.4%), and HBV (1.8%). Significant differences were observed in age groups (P = .054), gender (P = 0.016), ethnicity (P = .004), and HCV genotype (P ≤ .001). Socioeconomic status of lower and middle classes was affected more than the upper class (P = .030); marital status (P ≤ .001), diabetes mellitus (P = .013), viral load (P = .051), AST (P = .012), and ALT (P = .015) also showed significant differences.

| Treatment regimens | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | SOF + DCV 12 W (n = 944) | SOF + DCV + RBV 12 W (n = 41) | SOF + RBV 12 W (n = 8) | Total (n = 993) | P value |

| Age, y | 45.57 (18-90) | 45.44 (19-75) | 52.63 (33-62) | 45.62 (18-90) | .288 |

| Age groups, y | .054 | ||||

| Adults (18-60) | 832 (88.1%) | 38 (92.7%) | 5 (62.5%) | 875 (88%) | |

| Elders (>60) | 112 (11.9%) | 3 (7.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 118 (12%) | |

| Gender | .016 | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 433 (96.7%) | 10 (2.2%) | 5 (1.1%) | 448 (45%) | |

| Female, n (%) | 511 (54.1%) | 31 (75.6%) | 3 (37.5) | 545 (55%) | |

| Weight, kg | 59.22 (12.2-124) | 65.83 (37.8-97) | 73.66 (59-97) | 59.55 (12.2-124) | .089 |

| Height, cm | 153.06 (32-182) | 153.06 (133-172) | 156.50 (151-1161) | 153.10 (32-182) | .928 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.05 (2-51.61) | 27.96 (19.71-38.86) | 30.04 (22.76-38.86) | 25.18 (2-51.61) | .097 |

| Ethnicity | .004 | ||||

| Punjabi | 581 (61.5%) | 19 (46.3%) | 4 (50.0%) | 604 (60.8%) | |

| Pathan | 296 (31.4%) | 17 (41.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 314 (31.6%) | |

| Balochi | 42 (4.4%) | 5 (12.2%) | 2 (25.0%) | 49 (4.9%) | |

| Sindhi | 25 (2.6%) | – | 1 (12.5%) | 26 (2.6%) | |

| HCV genotype | <.001 | ||||

| 1 | 1 (0.1%) | – | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (0.2%) | |

| 2 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (2.4%) | – | 2 (0.2%) | |

| 3 | 942 (99.8%) | 40 (97.6%) | 7 (87.5%) | 989 (99.6%) | |

| Resident | .809 | ||||

| Rural | 391 (41.4%) | 15 (36.6%) | 3 (37.5%) | 409 (41.2%) | |

| Urban | 553 (58.6%) | 26 (63.4%) | 5 (62.5%) | 584 (58.8%) | |

| Socioeconomic status | .030 | ||||

| Low | 307 (32.5%) | 17 (41.5%) | – | 324 (32.6%) | |

| Middle | 478 (50.6%) | 15 (36.6%) | 4 (50%) | 497 (50.1%) | |

| High | 159 (16.8%) | 9 (22%) | 4 (50%) | 172 (17.3%) | |

| Education | .153 | ||||

| No | 203 (21.5%) | 10 (24.4%) | 5 (62.5%) | 218 (22%) | |

| Primary | 390 (41.3%) | 15 (34.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | 406 (40.9%) | |

| Secondary | 291 (30.8%) | 13 (31.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 305 (30.7%) | |

| Tertiary | 60 (6.4%) | 3 (7.3%) | 1 (12.5%) | 64 (6.4%) | |

| Marital status | <.001 | ||||

| Single | 383 (40.6%) | – | – | 383 (38.6%) | |

| Married | 561 (59.4%) | 41 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 610 (61.4%) | |

| Employment | .067 | ||||

| Employed | 381 (40.4%) | 24 (58.5%) | 3 (37.5%) | 408 (41.1%) | |

| Unemployed | 563 (59.6%) | 17 (41.5) | 5 (62.5%) | 585 (58.9%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| DM | 255 (27.0%) | 3 (7.3%) | 1 (12.5%) | 259 (26.1%) | .013 |

| HTN | 110 (11.7%) | 4 (9.8%) | – | 114 (11.5%) | .553 |

| CKD | 61 (6.5%) | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (12.5%) | 63 (6.3%) | .453 |

| IHD | 39 (4.1%) | 4 (9.8%) | – | 43 (4.3%) | .186 |

| HIV | 4 (0.4%) | – | – | 4 (0.4%) | .901 |

| HBV | 18 (1.7%) | – | – | 18 (1.8%) | .621 |

| Cirrhosis | .359 | ||||

| Absent | 906 (96%) | 41 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 955 (96%) | |

| Present | 38 (4%) | – | – | 38 (4%) | |

| Child-Pugh score | .548 | ||||

| Class A | 938 (99.4%) | 41 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 987 (99.4%) | |

| Class B | 6 (0.6%) | – | – | 6 (0.6%) | |

| RVR | .001 | ||||

| No | 116 (12.3%) | 9 (22%) | 4 (50%) | 129 (13%) | |

| Yes | 828 (87.7%) | 32 (78%) | 4 (50%) | 864 (87%) | |

| ETR | .002 | ||||

| No | 31 (3.3%) | 3 (7.3%) | 2 (25%) | 36 (4%) | |

| Yes | 913 (96.7%) | 38 (92.7%) | 6 (75%) | 957 (96%) | |

| SVR12 | <.001 | ||||

| No | 14 (1.5%) | 4 (9.8%) | 2 (25%) | 20 (2%) | |

| Yes | 930 (98.5%) | 37 (90.2%) | 6 (75%) | 973 (98%) | |

| Previous experience | .001 | ||||

| Naive | 864 (91.5%) | 33 (80.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 902 (91%) | |

| IFN experienced | 80 (8.5%) | 8 (19.5%) | 3 (37.5%) | 91 (9%) | |

| Viral load | .051 | ||||

| ≥800.000 IU/mL | 281 (29.8%) | 5 (12.2%) | 2 (25%) | 288 (29%) | |

| <800.000 IU/mL | 663 (70.2) | 36 (87.8%) | 6 (75%) | 705 (71%) | |

| HB (g/dL) | 13.018 (5.3-19.1) | 12.944 (9.3-17.1) | 13.925 (10.6-17.4) | 13.022 (5.3-19) | .477 |

| WBCs ( × 109/L) | 7.42 (2-17) | 7.10 (3-10) | 7.81 (4-10) | 7.41 (2-17) | .512 |

| PLT ( × 109/L) | 218.95 (19-610) | 209.49 (53-395) | 159.63 (75-339) | 218.08 (19-610) | .149 |

| TBR, μmol/L | 12.21 (1-183) | 10.26 (3-55) | 14.00 (7-26) | 12.14 (1-183) | .769 |

| ALP, IU/L | 92.22 (28-621) | 92.20 (29-270) | 91.38 (28-250) | 250 (28-621) | .999 |

| AST, IU/L | 151.11 (7-1454) | 148.91 (19-1168) | 363.13 (30-1161) | 153.06 (7-1454) | .012 |

| ALT, IU/L | 103.97 (24-629) | 109.94 (34-330) | 175.13 (54-505) | 104.89 (24-629) | .015 |

- Note: Data are presented as mean (range) or n (%). P value for continuous variables is calculated by one-way ANOVA, P value for categorical variables is calculated by Pearson χ2 test by comparing three groups.

- Abbreviations: ALP, Alkaline phosphatase; ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DAA, direct-acting antivirals; DCV, daclatasvir; DM, diabetes mellitus; ETR, end-of-treatment response; HB, Hemoglobin; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTN, hypertension; IFN, interferon; IHD, ischemic heart disease; PLT, platelets; RBV, ribavirin; RVR, Rapid virological response; SOF, Sofosbuvir; SVR12, Sustained virological response; TBR, total bilirubin; WBCs, white blood cells.

3.2 Treatment regimens

Among the 993 patients with chronic HCV infection, 944 (95.1%) patients were in DCV + SOF group, 41(4.1%) patients in DCV + SOF + RBV group, and 8 (28.1%) patients in SOF + RBV group (Figure 1).

3.3 Treatment response and SVR predictors

The overall SVR12 was 98% (973 of 993). In univariate analysis, it was identified that patients who achieved SVR12 when compared with those who did not achieve SVR12 showed statistically significant differences at various parameters. These included relationship in age, socioeconomic status, education, race, marital status, hypertension, cirrhosis, child-Pugh score, treatment given, RVR, ETR, prior treatment, viral load, AST and ALT. However, in multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, patients’ education status, treatment, viral load and ALT had a statistically significant association with the sustained viral response at 12 weeks (SVR 12). Educated patients were more likely to achieve SVR than non-educated as shown in Table 2. Furthermore, combination therapy to achieved SVR 12 (sofosbuvir + daclatasvir) showed significant results compared with other treatment regimens (OR, 31.23; 95% CI, 2.179-447.813, P = .011). Similarly, patients with lower viral loads, that is less than 800.000 IU/mL showed good response to treatment as compared with higher viral loads (SVR12: OR, 20.31; 95% CI, 1.549-266.519; P = .022). Higher ALT levels were also less likely to achieve SVR12 (OR, 0.093; 95% CI, 0.014-0.611; P = .013). This model fit was based on nonsignificant Hosmer Lemeshow test (P = 1) and an overall classification percentage of 98.7% from the classification table. SVR12 was not affected by HIV or HBV status, the presence of comorbidities, cirrhosis or previous treatment (Table 2).

| Variables | SVR12 (No. %) | Univariate analysis OR (95% CI) | P value | Multivariate analysis OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 440 (98.2) | 8 (1.8) | Reference | .643 | NA | |

| Female | 553 (97.8) | 12 (2.2) | 1.238 (0.502-3.056) | |||

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18-60 | 862 (98.5) | 13 (1.5) | Reference | .003 | Reference | |

| > 60 | 111 (94.1) | 7 (5.9) | 4.182 (1.634-10.703) | 1.420 (0.112-18.060) | .787 | |

| HCV Genotype | ||||||

| 1 | 2 (100) | – | Non-computable | |||

| 2 | 2 (100) | – | ||||

| 3 | 969 (98) | 20 (2) | ||||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Low | 319 (98.5) | 5 (1.5) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Middle | 489 (98.4) | 8 (1.6) | 1.044 (0.338-3.219) | .941 | 0.269 (0.022-3.313) | .305 |

| High | 165 (95.9) | 7 (4.1) | 2.707 (0.846-8.659) | .093 | 0.224 (0.016-3.185) | .269 |

| Education | ||||||

| No | 205 (94) | 13 (6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Primary | 404 (99.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0.078 (0.017-0.349) | .001 | 36.425 (1.487-892.175) | .028 |

| Secondary | 303 (99.3) | 2(0.7) | 0.104 ((0.023-0.466) | .003 | 12.268 (1.237-121.658) | .032 |

| Tertiary | 61 (95.3) | 3 (4.7) | 0.776 (0.214-2.810) | .699 | 0.576 (0.037-8.976) | .694 |

| Race | ||||||

| Punjabi | 595 (98.2) | 9 (1.8) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Pathan | 310 (99) | 4 (1) | 0.853 (0.261-2.792) | .793 | 2.441 (0.271-21.945) | .426 |

| Balochi | 46 (93.9) | 3 (6.1) | 4.312 (1.128-16.476) | .033 | 3.523 (0.041-305.376) | .580 |

| Sindhi | 22 (88) | 4 (12) | 12.02 (3.436-42.0511) | <.001 | 3.209 (0.024-425.812) | .640 |

| Resident | ||||||

| Rural | 402 (98.3) | 7 (1.7) | Reference | NA | ||

| Urban | 571 (97.8) | 13 (2.2) | 1.307 (0.543-3.306) | .571 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 381 (99.5) | 2 (0.5) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Married | 592 (97) | 18 (3) | 5.792 (1.336-25.105) | .019 | 0.276 (0.019-3.936) | .342 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 401 (98.3) | 7 (1.7) | Reference | NA | ||

| Unemployed | 572 (97.8) | 13 (2.2) | 1.302 (0.515-3.292) | .577 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | .533 | |||||

| No | 718 (97.8) | 16 (2.2) | Reference | NA | ||

| Yes | 255 (98.5) | 4 (1.5) | 0.704 (0.233-2.125) | |||

| Hypertension | ||||||

| No | 863 (98.2) | 16 (1.8) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 110 (96.5) | 4 (3.5) | 1.961 (0.644-5.972) | .236 | 0.116 (0.010-1.326) | .083 |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||||

| No | 911 (98) | 19 (2) | Reference | NA | ||

| Yes | 62 (98.4) | 1 (1.6) | 0.773 (0.102-5.872) | .804 | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | ||||||

| No | 931 (98) | 19 (2) | Reference | NA | ||

| Yes | 42 (97.7) | 1 (2.3) | 1.167 (0.153-8.923) | .882 | ||

| HIV | ||||||

| No | 973 (98.4) | 16 (1.6) | Non-computable | NA | ||

| Yes | – | 4 (100) | ||||

| HBV | ||||||

| No | 955 (97.9) | 20 (2.1) | Non-computable | NA | ||

| Yes | 18 (100) | – | ||||

| Cirrhosis | ||||||

| Absent | 938 (98.2) | 17 (1.8) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 35 (92.1) | 3 (7.9) | 0.211 (0.059-0.755) | .017 | 0.103 (0.009-1.193) | .069 |

| Child-pugh score | ||||||

| Class A | 968 (98.1) | 19 (1.9) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Class B | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0.098 (0.011-0.881) | .038 | 1.171 (0.003-540.931) | .960 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| SOF + DCV + RBV | 37 (90.2) | 4 (9.8) | Reference | Reference | ||

| SOF + DCV | 930 (98.5) | 14 (1.5) | 7.181 (2.254-22.880) | .001 | 31.239 (2.179-447.813) | .011 |

| SOF + RBV | 6 (75) | 2 (25) | 0.324 (0.048-2.177) | .246 | 12.032 (0.185-780.994) | .243 |

| RVR | ||||||

| No | 117 (90.7) | 12 (9.3) | Reference | Non-computable | ||

| Yes | 856 (99.1) | 8 (0.9) | 10.974 (4.394-27.406) | <.001 | ||

| ETR | ||||||

| No | 24 (66.7) | 12 (33.3) | Reference | Non-computable | ||

| Yes | 949 (99.2) | 8 (0.8) | 59.312 (22.215-158.359) | <.001 | ||

| Prior treatment | ||||||

| Treatment Naive | 891 (98.8) | 11 (1.2) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Pretreated with IFN | 82 (90.1) | 9 (9.9) | 8.890 (3.580-22.075) | <.001 | 0.119 (0.012-1.196) | .071 |

| Viral load | ||||||

| ≥800.000 IU/mL | 273 (94.8) | 15 (5.2) | Reference | Reference | ||

| <800.000 IU/mL | 700 (99.3) | 5 (0.7) | 0.130 (0.047-0.361) | <.001 | 20.319 (1.549-266.519) | .022 |

| ALP | ||||||

| ≤168 | 97 (100) | – | Non-computable | |||

| >168 | 876 (97.8) | 20 (2.2) | ||||

| AST | ||||||

| ≤34 | 207 (99) | 2 (1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| >34 | 668 (97.7) | 16 (2.3) | 2.479 (0.565-10.871) | .229 | 0.291 (0.021-3.995) | .356 |

| ALT | ||||||

| ≤35 | 743 (99.1) | 7 (0.9) | Reference | Reference | ||

| >35 | 185 (93.4) | 13 (6.6) | 7.459 (2.934-18.958) | <.001 | 0.093 (0.014-0.611) | .013 |

- Note: All variables with P-value < .25 were included in the multivariate analysis.

- Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; DCV, daclatasvir; ETR, end-of-treatment response; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency viruses; IFN, interferon; OR, odds ratio; RBV, ribavirin; RVR, rapid virological response; SOF, sofosbuvir; SVR, sustained virological response.

3.4 Comparison of different treatment regimens

In sofosbuvir + daclatasvir group, 98.5% patients achieved SVR. In multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, education status (OR, 42.037; 95% CI, 1.596-1107.522, P = .025) and elevated ALT (OR, 0.003; 95% CI, 0.000-0.252; P = 0.010) had statistically significant association with SVR12 (Table 3).

| Responses | SVR12 rate | Univariate P value | Multivariate P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 930/944 (98.5) | ||

| Age groups, y | |||

| Adults (18-60) | 823/832 (98.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Elders (>60) | 107/112 (95.5) | .010 | .685 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 426/433 (98.4) | Reference | |

| Female | 504/511 (98.6) | .755 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Punjabi | 574/582 (98.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Pathan | 296/296 (100) | .994 | .992 |

| Balochi | 39/42 (92.9) | .014 | .791 |

| Sindhi | 21/24 (87.5) | .001 | .954 |

| HCV genotype | |||

| 1 | 1/1 (100) | Reference | |

| 2 | 1/1 (100) | 1.000 | |

| 3 | 928/942 (98.5) | 1.000 | |

| Resident | |||

| Rural | 386/391 (98.7) | Reference | |

| Urban | 544/553 (98.4) | .663 | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Low | 302/307 (98.4) | Reference | |

| Middle | 472/478 (98.7) | .665 | |

| High | 156/159 (98.1) | .839 | |

| Education | |||

| No | 194/203 (95.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Primary | 390/390 (100) | .993 | .989 |

| Secondary | 289/211 (99.3) | .016 | .025 |

| Tertiary | 57/60 (95) | .854 | .832 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 381/383 (99.5) | Reference | Reference |

| Married | 549/561 (97.9) | .063 | .231 |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 375/381 (98.4) | Reference | |

| Unemployed | 555/563 (98.6) | .848 | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| DM | 251/255 (98.4) | .895 | |

| HTN | 107/110 (97.3) | .261 | |

| CKD | 61/61 (100) | .997 | |

| IHD | 38/39 (97.4) | .574 | |

| HIV | 0/4 (00) | .999 | |

| HBV | 18/18 (100) | .999 | |

| Cirrhosis | |||

| Absent | 895/906 (98.2) | Reference | Reference |

| Present | 35/38 (92.1) | .143 | .091 |

| Child-Pugh score | |||

| Class A | 925/938(98.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Class B | 5/6(83.3) | .019 | .980 |

| RVR | |||

| No | 106/116 (91.4) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 824/828 (99.5) | <.001 | .997 |

| ETR | |||

| No | 21/31 (67.7) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 909/913 (99.6) | <.001 | .995 |

| Previous experience | |||

| Naive | 857/864 (99.2) | Reference | Reference |

| IFN experienced | 73/80 (91.3) | <.001 | .098 |

| Viral load | |||

| ≥800.000 IU/mL | 271/281 (96.4) | Reference | Reference |

| <800.000 IU/mL | 659/663 (99.4) | .002 | .196 |

| Elevated ALP | 838/852 (98.4) | .997 | |

| Elevated AST | 636/646 (98.5) | .557 | NA |

| Elevated ALT | 177/187 (94.7) | <.001 | .010 |

- Note: All variables with P value < .25 were included in the multivariate analysis.

- Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ETR, end-of-treatment response; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency viruses; HTN, hypertension; IFN, interferon; IHD, ischemic heart disease; OR, odds ratio; RVR, rapid virological response; SVR, sustained virological response.

Sofosbuvir + daclatasvir + ribavirin group achieved 90.2% SVR rate as depicted in Table (Supporting Information). Presence of cirrhosis, prior treatment experience, elevated liver enzymes and other comorbid conditions did not exhibit significant association with SVR12 in multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. However viral load, employment and education status were significant factors in univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis.

Sofosbuvir + ribavirin group overall SVR 12 rate was reported as 75% as shown in Table (Supporting Information). In this group, no significant association was observed between SVR12 and any variable in multivariate analysis.

3.5 Rates of sustained virological response in chronic and cirrhotic HCV patients

The SVR rates were higher in chronic HCV patients (98.2%) as compared with cirrhotic patients (CC = 93.8%, DC = 83%). Sofosbuvir in combination with ribavirin was not as effective as the other combinations in chronic HCV patients with SVR rate 75%. However, only decompensated cirrhosis was difficult to treat group achieving 83% SVR rates than the rest of the patient groups. A highest SVR rate in all patient groups was achieved by sofosbuvir and daclatasvir combination (Table 4).

| Treatment regimen | Chronic HCV (no cirrhosis) | Compensated cirrhosis (CC) | Decompensated cirrhosis (DC) | Total (N = 993) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOF + DCV | 895/906 (98.8%) | 30/32 (93.8%) | 5/6 (83.3%) | 930/944 (98.5%) |

| SOF + DCV + RBV | 37/41 (90.2%) | – | – | 37/41 (90.2%) |

| SOF + RBV | 6/8 (75%) | – | – | 6/8 (75%) |

| Total | 938/955 (98.2%) | 30/32 (93.8%) | 5/6 (83.3%) | 973/993 (98%) |

- Abbreviations: DCV, daclatasvir; HCV, hepatitis C virus; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir; SVR, sustained virological response.

3.6 Adverse events reported by treatment regimen

Table 5 describes the association between treatment regimens and adverse events (AEs) reported during the study. Statistically significant association was observed between treatment regimens and skin rash (43.8%), Insomnia (33%), Oral ulcers (30.2%) and fatigue (16.6%).

| Treatment regimen | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse events | SOF + DCV (N = 944) | SOF + DCV + RBV (N = 41) | SOF + RBV (N = 8) | Total (N = 993) | P value |

| Headache | 551 (58.4%) | 19 (46.3%) | 7 (87.5%) | 577 (58.1%) | .074 |

| Nausea | 521 (55.2%) | 25 (61%) | 3 (37.5%) | 549 (55.3%) | .457 |

| Abdominal pain | 442 (46.8%) | 19 (46.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 464 (46.7%) | .870 |

| Myalgia | 698 (73.9%) | 28 (68.3%) | 8 (100%) | 734 (73.9%) | .174 |

| Arthralgia | 566 (60%) | 26 (63.4%) | 5 (62.5%) | 597 (60.1%) | .898 |

| Dizziness | 154 (16.3%) | 9 (22%) | 1 (25.5%) | 164 (16.5%) | .607 |

| Insomnia | 320 (33.9%) | 8 (19.5%) | – | 328 (33%) | .022 |

| Fatigue | 153 (16.2%) | 12 (29.3%) | – | 165 (16.6%) | .040 |

| Skin rash | 414 (43.9%) | 21 (51.2%) | – | 435 (43.8%) | .028 |

| Oral ulcers | 283 (30%) | 17 (41.5%) | – | 300(30.2%) | .051 |

- Abbreviations: DCV, daclatasvir; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir.

4 DISCUSSION

Development of DAA agents is the landmark in the treatment of HCV infection. This IFN-free treatment provides high SVR rates and tends to prevent liver disease progression. The availability of DAA regimens replaced IFN treatment for HCV therapy across the globe.12 A notable decline was observed in the prices of DAAs by the DAAs generics availability in 101 developing countries,20 but the scientific assessment is required for the efficacy of these generics. However, to design and to implement strategies regarding the treatment of HCV on a large scale, it is necessary to review the existing experience with DAAs in Pakistani population.

We report here a real-world experience with generic DCV and SOF with or without RBV as combination therapy and SOF with RBV as monotherapy for treating the patient with HCV-GT3. This is one of the largest reports presenting real-life data using this combination in treating HCV-GT3 patients from Pakistan. More than 90% of patients in Pakistan are infected with HCV-GT3,6 therefore, subgenotyping was not performed at baseline, thus this report is taken to represent results of HCV-GT3 treatment. DCV and SOF with or without RBV is recommended by both US treatment guidelines and European guidelines against HCV-GT3 irrespective of HCV treatment experience or cirrhosis status and subgenotype.21

In this study, the overall clinical effectiveness (SVR12) of DCV + SOF ( ± RBV) treatment was 98% (98.8% without RBV and 90.2% with RBV). These findings are comparable with the Indian study where SVR12 rate was 96% in GT3.22 Likewise, also, these results are aligned with ALLY-3+ studies where ≥96% SVR12 rates achieved in GT3 patients.23 This response rate is in agreement with the results of Sulkowski et al24 where HCV-GT1, 2 and 3 achieved 89% to 98% SVR12 rate depending on the genotype. Another large cohort of Egypt with GT4 was analyzed by Omar et al25 with 95.1% SVR12 rate (95.4% without RBV and 94.7% with RBV). Belperio et al26 reported SVR12 rate in GT2 (94.5% without RBV and 88.1% with RBV) and GT3 (90.8% without RBV and 88.1% with RBV). In comparison to our response rate, similar findings are reported in other studies.22, 27-30 These results supported that the chance of achieving a cure was higher with DCV + SOF then the DCV + SOF + RBV. It shows the use of RBV did not improve the SVR rate. Moreover, a study reported that RBV should be avoided due to its associated adverse effects and anemia.31

In our study, the regimen DCV and SOF found to be superior to the previous standard of care SOF and RBV that shows lower SVR12 (75%) in the treatment of CHC GT3. This is in agreement with the results of the study conducted by del Rio-Valencia et al30 where the response rate was 75% and Jacobson et al32 where they reported 78% SVR12. This indicates that only SOF is less effective than other combinational therapies. Thus, a longer period of therapy is required to remove remaining viral reservoirs or the addition of other DAAs to the treatment.

For HCV patients with GT3, prior treatment experience and advanced liver disease are found to be significant predictors of SVR rate in multiple studies. In the current study, treatment-naive patients treated with DCV + SOF achieved higher SVR12 (99%) as compared with pretreated patients (90%) of GT3. This is in line with the results published by Nelson et al28 where SVR12 rates were 90% in treatment-naive and 86% in pretreated patients and SVR12 was 84% and 80% in treatment-naive and pretreated patients, respectively, in a study by Umar et al.33 Similarly, in our study, cirrhotic patients treated with DCV + SOF achieved (92% SVR12) as compared with non-cirrhotic patients (98% SVR12). In compliance with our study findings, SVR12 rates greater than 90% in cirrhotic patients was reported in respective studies conducted elsewhere.22, 27-29, 31, 34 The present data indicate that DCV + SOF achieved high SVR rates even among cirrhotic patients irrespective of RBV use.

Cure rates above 90% have been reported using different combinations of all-oral DAAs in CHC patients treated in several clinical trials.35, 36 Initial real-world results support these findings, but the efficacy tends to be lower mainly due to predictors of lower SVR rate in registration trials. Furthermore, doctor's limited expertise using these new DAAs led to the impairment of their success.35-42 Given the high SVR rates with DAAs, treatment failure studies are comparatively low and largely influenced by treatment strategies explored and drug combinations.41, 43, 44 Furthermore, predictors of SVR rates are not uniform in different trials making it difficult to make comparisons. Baseline variables associated with a lower SVR rate includes the presence of natural polymorphisms at the viral nonstructural genes that reduce drug susceptibility, infection with HCV GT1 and GT3, liver cirrhosis, prior treatment experience, and elevated viral load.5, 43, 44

In our multivariate models, significant predictors of SVR12 were patients’ education status, treatment regimen, viral load, and ALT. Educated patients achieved a higher rate of SVR12 as compared with uneducated patients. During therapy, uneducated people with an incomplete profile (n = 198) were excluded from the study due to the premature drug cessation. However, among the included study participants, 13 of 20 treatment failure cases were uneducated due to recurrent missing doses. In agreement with our results, various studies reported that higher education level is associated with better compliance and treatment outcomes.45-48

In our study, those patients who were treated with DCV + SOF significantly achieved higher SVR12 (P = .011) than those who were treated with other treatments like DCV + SOF + RBV and SOF + RBV. These findings are in alliance with the results of a study by Welzel et al.29 Patients with viral load <800.000 IU/mL significantly achieved higher SVR12 (P = .022) than viral load ≥800.000 IU/mL. These findings are comparable with the results of a Brazilian study18 and Lourianne study.15 In our study, the negative predictor of SVR12 was elevated ALT level. Those patients who had elevated ALT levels were less likely to achieve higher SVR12 (P = .013). Our findings are supported by a study conducted by Huynh et al49 where ALT levels were associated with SVR rate. In another study, the authors reported that ALT can serve as a potential biochemical marker for HCV treatment response.50 A study conducted by Khan et al51 reported that baseline ALT level was significantly associated with SVR rate in multivariate analysis.

As the treatment with generic DAAs is a safe and effective alternative toward the elimination of HCV,52 the safety profile of these generic DAAs in our study was well tolerated. The most common AEs were skin rash, insomnia, oral ulcers, and fatigue which is comparable with study findings conducted by Leroy et al,23 where fatigue and insomnia were major side effects. In our study apart from these major AEs, the patient also complained of skin rash (43.8%) and oral ulcers (30.2%). A study from Egypt reported a skin rash up to 9.8% of the patients using generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.20 Oral ulcers have been found 8.8% with this combination in Pakistani population.33

5 CONCLUSIONS

The findings of the current study confirmed that second-generation generic DAAs (sofosbuvir with daclatasvir) are highly effective for CHC patient's treatment in Pakistan, particularly for genotype 3. Current SVR rates with sofosbuvir-based DAAs were higher as compared with previous therapies. Host factors like education level, treatment strategy, viral load, and ALT were seemed to be the predictors of SVR rate. The safety profile of these DAAs was well tolerated and safe. A large multicenter prospective study is recommended to confirm the present findings.

6 STUDY LIMITATIONS

This study was limited to only 3 months follow-up. A multicenter study with a longer follow-up of 6 months is recommended. Furthermore, only host factors being assessed in this study, the viral factors (resistance-associated substitutions) need to be assessed for the efficacy of the therapeutic regimens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all the hospital and laboratory staff, and patients who participated in this study. This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors (SM, AM, MU, AK, SS, and SM) made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study. SM and AK made substantial contributions to the acquisition and analysis of the data. SM drafted the manuscript and AM, MU, SS, and SM were involved in critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Study is supervised by SM.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the ethical review board of Rawalpindi Medical University, Holy family, Institute of Biomedical and Genetic Engineering and National University of Science and Technology (IRB-130). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this current article. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.