Assessing patient perceptions of cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy

Abstract

Pregnant women impacted by cytomegalovirus (CMV) make clinical decisions despite uncertain outcomes. Intolerance of uncertainty score (IUS) is a validated measure of tendency for individuals to find unacceptable that a negative event might occur. We investigated patient perceptions of CMV infection during pregnancy and correlated IUS and knowledge with decision-making. Electronic questionnaire was sent to women from July to August 2017. The questionnaire evaluated knowledge of CMV, IUS, and responses regarding management to three clinical scenarios with escalating risk of CMV including choices for no further testing, ultrasound, amniocentesis, or abortion. For each scenario, logistic regression was used to model IUS on responses. A total of 815 women were included. The majority of participants was white (63.1%) and 42% had a postgraduate degree. Over 70% reported that they had not previously heard of CMV. In the scenario with only CMV exposure, participants with increasing IUS were more likely to choose abortion (odds ratio [OR] = 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.01, 1.06) and no further testing (OR = 0.97; 95% CI: 0.95, 0.99). In the scenario with mild ultrasound findings in setting of CMV exposure, increasing IUS was associated with higher odds of choosing no further testing (OR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94, 0.99). No significant association was observed between IUS and responses in the scenario with severe ultrasound abnormalities in setting of CMV exposure. The majority of patients had no knowledge of CMV. Higher IUS was associated more intervention in low severity scenarios, but in severe scenarios, IUS was not associated with participants' choices.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is common in the general population, with more than half of adults being infected by middle age.1 Most healthy children and adults experience no symptoms or sequela of infection. However, CMV infection during pregnancy can result in congenital infection of the fetus. In the United States, up to 1% to 4% of seronegative women will have primary CMV infection during a pregnancy, and about 40% of these women will pass the virus to their infants. The range of disease severity of congenital CMV is very wide from normal development to sensorineural hearing loss, chorioretinitis, and cognitive or neurologic deficits that may be mild or severe.2

Although CMV is the most common congenital viral infection in the United States, pregnant women are not routinely screened for CMV infection due to the lack of available therapies. If exposure is suspected, testing for primary infection involves serologic screening. Amniocentesis for CMV polymerase chain reaction may provide additional information about the likelihood of fetal infection. Ultrasound findings may be present in infected infants as well, but absence of findings is common even among affected fetuses.3, 4

At this time, there is no known efficacious treatment to mitigate fetal infection in an infected mother and treatment outside of research protocols is not recommended. Some studies have suggested that hygiene education in pregnant patients may decrease the risk of maternal infection or seroconversion; however, there are no randomized trials demonstrating efficacy of maternal hygiene education to prevent congenital infection.5, 6

Given the variable outcomes of congenital infection and in the absence of effective preventive measures or treatment, the prognosis is difficult to predict. Women participate in the decision of whether to pursue maternal testing, possible follow-up fetal testing, or pregnancy termination in suspected CMV infection often without definitive information on precise prognosis. Intolerance to uncertainty score (IUS) measures individuals' responses to uncertainty, ambiguity, and the future to determine the overall tendency of an individual to find it unacceptable that a negative event might occur. Good convergent and discriminate validity, as well as internal consistency, have been demonstrated.7 The IUS tool has also been used extensively in research in the field of psychiatry.8-10 In this study, we sought to understand patient perceptions and tolerance of risk with regard to congenital CMV infection and to determine factors that may influence patient decision-making and inform provider counseling.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

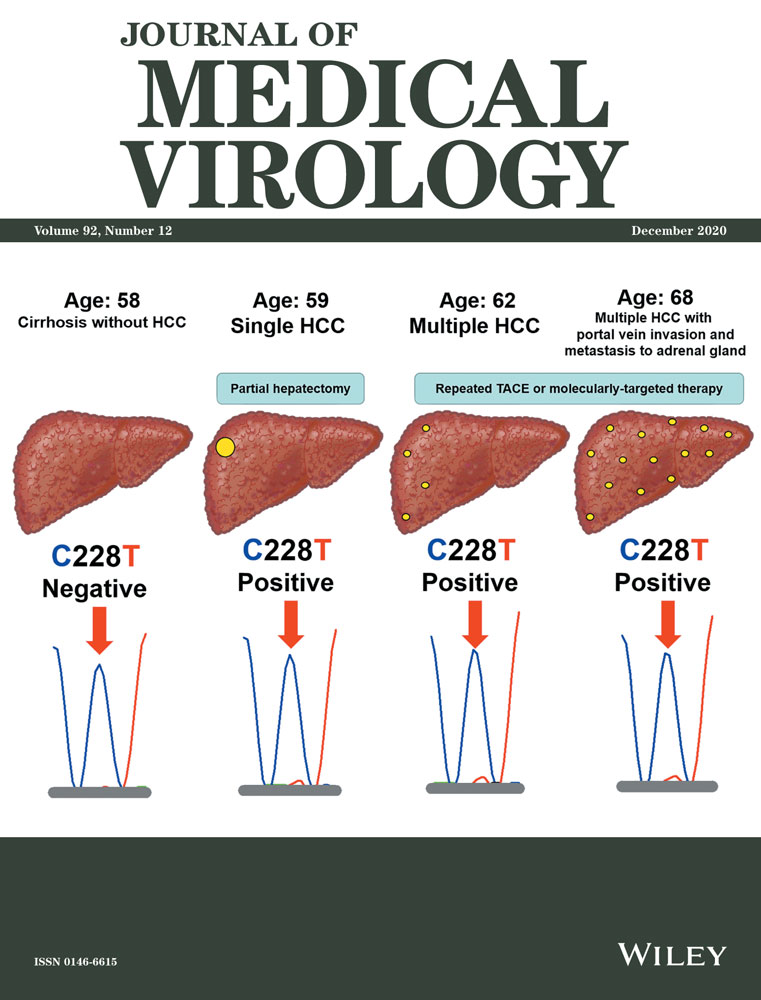

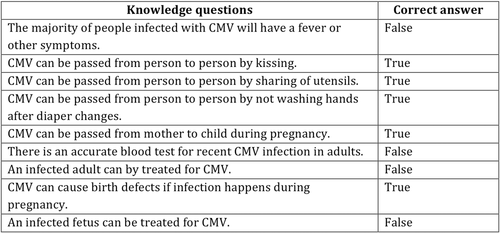

A questionnaire was administered through our institution to all women seen for a clinic appointment in one of six Duke Women's Care clinics from 9 July to 18 August 2017. Duke University Institutional review board determined the study to be exempt under protocol Pro00079994. Following their appointment, a link to the questionnaire was sent to the patient through an online patient portal. Women who were pregnant or considering pregnancy in the future were included in this study. Women who were unable or unwilling to complete the online questionnaire were inherently excluded. The questionnaire included 9 true or false questions that evaluated the participant's knowledge of CMV (Figure 1), 12 IUS questions (Figure 2), demographic information, and 3 hypothetical scenarios. The number of correct answers in the knowledge section of the questionnaire was tallied to determine the subjects' knowledge score (KS). IUS was calculated by summing the 5-point Likert scale answers, 1 for “not at all characteristic of me” to 5 for “entirely characteristic of me,” on a validated 12-item questionnaire. IUS has a possible score of 12 to 60. A higher numerical score correlates with higher intolerance to uncertainty. Participants were also asked to respond to hypothetical clinical scenarios. The three clinical scenarios presented participants with exposures to CMV in pregnancy that became increasingly more severe. In scenario 1, the patient had exposure to children known to be infected with CMV and positive serologic studies. In scenario 2, fetal growth restriction is diagnosed in the setting of serologic evidence of CMV infection. The third scenario presented ultrasound findings including microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, and ascites in the setting of serologic evidence of CMV infection. Participants were asked to choose their preferred management for each of the three hypothetical scenarios presented in the questionnaire including amniocentesis, ultrasound, abortion, or no further testing. These four decisions defined the primary outcomes of the study. Demographics such as age, race, ethnicity, and education were collected from the participants' responses from the questionnaire.

Means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for continuous variables, while frequencies and proportions were calculated for categorical variables. Pearson's correlation and Kruskal-Wallis test (or analysis of variance) were used to investigate the association between IUS/KS and each demographic characteristic. Amniocentesis (yes/no), ultrasound (yes/no), abortion (yes/no), and no further testing (yes/no) were treated as binary outcomes in each scenario, while IUS and KS were the exposures. The association between each exposure and outcome was investigated using the logistic regression model. Odds ratio (OD) (95% confidence interval [CI]) and P value were presented for each model. All analyses were performed using R Core team version 3.4.2 (2013).

3 RESULTS

A total of 1098 patients participated in the initial questionnaire. Among these, 815 were pregnant at the time of the questionnaire or indicated that they may become pregnant in the future and thus were included in the analysis. The remaining of the patients did not meet these inclusion criteria, and, thus, were not invited to complete the study. The average age of the participants was 31.1 (SD, 5.5). The participants were primarily white (63.1%), non-hispanic (93.1%), and postgraduate (42%) (Table 1). Over 70% of the participants had no previous knowledge of CMV infection. The primary setting in which some participants had heard of CMV was through school or training (15.3%). A total of 175 participants completed all KS questions. There was no significant association between KS and education level (P = .68), age (P = .23), race (P = .29), or ethnicity (P = .91). A total of 685 participants completed all IUS questions. There was no significant association between IUS and age (P = .09), race (P = .10), or ethnicity (P = .37). IUS was associated with education level (P = .003). The IUS among participants with some high school (HS) was highest (median = 32; IQR = 21, 40) compared to participants with some college or associate degree (median = 24; IQR = 20, 32), and participants who completed an undergraduate or a postgraduate degree (median = 28; IQR = 22, 34).

| Characteristics | IUS < 34 | IUS ≥ 34 |

|---|---|---|

| No. 501 | No. 184 | |

| Age | ||

| Median (IQR) | 32 (28, 35) | 31 (27, 34) |

| N | 501 | 184 |

| Missing | … | 3 (1.63%) |

| Race | ||

| Black/African American | 97 (19.4%) | 47 (25.5%) |

| White/Caucasian | 335 (66.9%) | 115 (62.5%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 40 (8%) | 17 (9.2%) |

| Other | 29 (5.8%) | 5 (2.7%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 33 (6.6%) | 11 (6.0%) |

| Non-hispanic | 468 (93.4%) | 173 (94.0%) |

| Education level | ||

| Some high school /high school degree/GED | 19 (3.8%) | 18 (9.8%) |

| Some college/associates degree | 101 (20.2%) | 27 (14.7%) |

| Completed degree/postgraduate degree | 381 (76%) | 139 (75.5%) |

- Note: Intolerance to uncertainty (IUS) score of ≥34 represents the women in the top quartile of IUS score.

- Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; GED, general educational development; IQR, interquartile range.

Among the 685 participants who completed all the IUS questions, 607 participants completed scenario 1, in which a patient had a low-risk exposure to CMV at the workplace. Participants with a higher IUS were more likely to choose abortion (OR = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.06; P = .004) than those with a lower IUS indicating that for a one-unit increase in IUS, there is a 4% increase in the odds of choosing abortion (Table 2). Conversely, higher IUS was associated with lower odds of choosing no further testing (OR = 0.97; 95% CI: 0.95, 0.99; P = .003) compared to lower IUS. A total of 598 participants completed all IUS questions for scenario two, in which there was a mild ultrasound finding in the setting of CMV exposure. Similar to scenario 1, higher IUS was associated with lower odds of choosing no further testing (OR = 0.97; 95% CI: 0.94, 0.99; P = .002) compared to lower IUS (Table 2). A total of 591 participants completed scenario 3, in which there were severe ultrasound findings in the setting of CMV exposure. No significant association between IUS and responses in scenario 3 was observed (Table 2). No significant association was observed between KS and responses in any scenario (Table 3).

| No | Yes | OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUS—Scenario 1—CMV exposure and positive serology | ||||

| Amniocentesis | 1.02 (0.997, 1.04) | .11 | ||

| Number | 245 (40.4%) | 362 (59.6%) | ||

| Median IUS (IQR) | 27 (21, 33) | 27 (22, 35) | ||

| Further Ultrasound | 1.02 (0.996, 1.05) | .09 | ||

| N | 98 (16.1%) | 509 (83.9%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 26.5 (21, 30.8) | 28 (22, 34) | ||

| Abortion | 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) | .004 | ||

| N | 503 (83.1%) | 102 (16.9%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 27 (22, 33) | 30 (23, 36.8) | ||

| No further testing | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | .003 | ||

| N | 416 (68.6%) | 190 (31.4%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 28 (22, 34.2) | 26 (20, 31.8) | ||

| IUS—Scenario 2-FGR and positive serology | ||||

| Amniocentesis | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | .39 | ||

| N | 193 (32.3%) | 405 (67.7%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 27 (22, 33) | 27 (22, 34) | ||

| Further Ultrasound | 1.004 (0.97, 1.04) | .81 | ||

| N | 60 (10%) | 538 (90%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 26.5 (21, 34) | 27 (22, 34) | ||

| Abortion | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | .10 | ||

| N | 481 (80.4%) | 117 (19.6%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 27 (22, 33) | 29 (23, 35) | ||

| No further testing | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | .002 | ||

| N | 440 (73.6%) | 158 (26.4%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 28 (22, 34) | 25 (20.2, 32) | ||

| IUS—Scenario 3—microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, and ascites with positive serology | ||||

| Amniocentesis | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | .39 | ||

| N | 118 (20%) | 473 (80%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 27 (22, 32) | 27 (22, 34) | ||

| Further Ultrasound | 1.001 (0.97, 1.03) | .96 | ||

| N | 61 (10.3%) | 530 (89.7%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 27 (20, 35) | 27 (22, 34) | ||

| Abortion | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | .07 | ||

| N | 333 (56.3%) | 258 (33.7%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 27 (22, 33) | 28 (22, 35) | ||

| No further testing | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | .28 | ||

| N | 487 (82.4%) | 104 (17.6%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 27 (22, 34) | 27 (22, 33) | ||

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FGR, fetal growth restriction; IQR, interquartile range; IUS, intolerance to uncertainty; OR, odds ratio.

| No | Yes | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KS—Scenario 1—CMV exposure | ||||

| Amniocentesis | 0.94 (0.78, 1.14) | .54 | ||

| N | 75 (47.2%) | 84 (42.8%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 7) | 6 (4.8, 7) | ||

| Ultrasound | 1.02 (0.80, 1.29) | .91 | ||

| N | 30 (18.9%) | 129 (81.1%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5.5 (5, 7) | 6 (5, 7) | ||

| Abortion | 0.88 (0.69, 1.13) | .31 | ||

| N | 131 (82.9%) | 27 (17.1%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 7) | 6 (5, 6) | ||

| No further testing | 0.89 (0.72, 1.09) | .26 | ||

| N | 115 (72.3%) | 44 (27.7%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 7) | 5 (4, 6.2) | ||

| KS—Scenario 2—FGR and CMV exposure | ||||

| Amniocentesis | 1.00 (0.82, 1.21) | 1.00 | ||

| N | 59 (37.3%) | 99 (62.7%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 7) | 6 (4.5, 7) | ||

| Ultrasound | 1.05 (0.76, 1.46) | .75 | ||

| N | 14 (8.9%) | 144 (91.1%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5.5 (5, 6.8) | 6 (5, 7) | ||

| Abortion | 0.96 (0.77, 1.20) | .71 | ||

| N | 123 (77.8%) | 35 (22.2%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 7) | 6 (5, 6) | ||

| No further testing | 0.89 (0.71, 1.11) | .31 | ||

| N | 122 (77.2%) | 36 (22.8%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 7) | 5 (4, 6.2) | ||

| KS—Scenario 3—microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, and ascites with CMV exposure | ||||

| Amniocentesis | 1.03 (0.82, 1.28) | .82 | ||

| N | 36 (22.8%) | 122 (77.2%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 7) | 6 (4.2, 7) | ||

| Ultrasound | 1.20 (0.91, 1.59) | .19 | ||

| N | 21 (13.3%) | 137 (86.7%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 6) | 6 (5, 7) | ||

| Abortion | 1.09 (0.91, 1.32) | .35 | ||

| N | 69 (43.7%) | 89 (56.3%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (4, 7) | 6 (5, 7) | ||

| No further testing | 0.81 (0.59, 1.11) | .19 | ||

| N | 142 (89.9%) | 16 (10.1%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5, 7) | 5 (4.8, 6) | ||

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMV, cytomegalovirus; FGR, fetal growth restriction; IQR, interquartile range; KS, knowledge score; OR, odds ratio.

4 DISCUSSION

We found that the majority of patients had not previously heard of CMV infection and patient knowledge of CMV was not correlated with the education level in this cohort. The primary setting in which patients had heard of CMV was not through their provider. This finding is consistent with the results of a 2007 questionnaire administered by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to practicing obstetrician-gynecologists that found only 44% of obstetrician-gynecologists counsel their patients about CMV infection in pregnancy.11 Previous studies have also shown that women's familiarity with CMV appears to be quite low, despite the relatively high prevalence of CMV infection in the United States.12 A survey completed by Cannon et al13 found that only 13% of women were familiar with CMV, and among women with children less than 19 years old, there were high rates of risk behaviors such as kissing on the lips and sharing cups, utensils, and food. A survey by Ross et al14 had similar findings. They found that only 14% of women had heard of CMV and their knowledge of conditions related to congenital CMV was quite poor. However, they did find that preventative hygiene practices would be generally acceptable.14

In addition to knowledge of congenital CMV, this study also investigates how women's knowledge may be associated with decisions on the management of pregnancy following CMV exposure. This has not been previously reported for CMV but has been studied for the Zika virus.15 Greater knowledge of the Zika virus was associated with consideration of termination for high risk of Zika virus infection, while low knowledge was associated with consideration of invasive testing despite low or no risk of Zika virus infection.15 This is contrary to our results given that KS was not associated with any specific response in the clinical scenarios.

Finally, this study also evaluated respondents' IUS and found that IUS was highest among participants with lower education level (some HS, HS degree, or general educational development) and a higher IUS predicted more aggressive interventions with low severity scenarios. IUS has been used to evaluate patient responses to obstetric ultrasound findings and genetic testing16 as well as in management and counseling of patients with cancer undergoing active surveillance of disease.17 In both of these clinical scenarios, like CMV in pregnancy, laboratory results and imaging may not be able to provide a definitive diagnosis or prognosis for conditions that may have life-altering repercussions. Patient IUS, therefore, has implications for patient counseling and behavioral interventions that may affect their medical decision-making and management.

Our findings show that all women require more counseling from their obstetrical providers regarding CMV in pregnancy to increase their knowledge. Furthermore, clinicians may need to consider patient factors when counseling a woman with exposure to CMV. For example, patients with higher IUS or a lower education level may need targeted CMV-related education and reassurance to assist them with their medical decision-making.

This study aims to answer a unique and important question regarding patient knowledge, tolerance of uncertainty, and preferences for the management of pregnancies that may be affected by the most common congenital infection in the United States. We were able to recruit a large sample size of greater than 800 participants who were either currently pregnant or considering a future pregnancy. Therefore, our cohort represents a population of primed to respond to the study questions. In addition, this study is applicable to practice as it may allow us to understand women's preferences after CMV exposure or infection and assist with counseling strategies.

However, we also recognize some significant limitations of this study. Our sample population limits the generalizability of the data given different racial groups and education levels were not equally represented. In addition, although all women were asked to complete the questionnaire after their clinic visit during the study period, only women who chose to complete the study could be included and, therefore, we have inherent response bias with our sample of convenience. In addition, despite a large number of participants, very few participants had awareness of CMV and, therefore, only a small proportion of our study population was able to complete the knowledge section of the questionnaire. Given that few participants had previously heard of CMV, KS was only available for 175 participants. Finally, some of the knowledge questions could be open to debate in a well-informed patient with significant medical knowledge. However, it is interesting to note that even this highly educated population had little knowledge regarding CMV.

Future questionnaires should attempt to identify other factors associated with providing successful CMV counseling, solicit more detailed information about CMV knowledge and counseling practices, and assess the impact of education on the intolerance of uncertainty.

In conclusion, many women are unaware of congenital CMV and require more education from their providers. In addition, having higher intolerance to uncertainty is associated with significant prenatal intervention for low-risk CMV exposure that is not replicated in higher risk scenarios. Given the association between intolerance to uncertainty and patient decision-making demonstrated in this study, future surveys should attempt to identify other factors associated with providing successful CMV counseling, solicit more detailed information about CMV knowledge and counseling practices, and assess the impact of education on the intolerance of uncertainty.