Abstract

While the etiology of breast cancer remains enigmatic, some recent reports have examined the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in breast carcinogenesis. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of HPV in breast cancer tissue using PCR analysis and sequencing. Fifty-four (54) fresh frozen breast cancers samples that were removed from a cohort of breast cancer patients were analyzed. Samples were tested for HPV using comprehensive PCR primers, and in situ hybridization was performed on paraffin embedded tissue sections. Findings were correlated with clinical and pathological characteristics. The HPV DNA prevalence in the breast cancer samples was 50% (27/54) with sequence analysis indicating all cases to be positive for HPV-18 type. While HPV patients were slightly younger, no correlation was noted for menopausal status or family history. HPV positive tumors were smaller with earlier T staging and demonstrated lesser nodal involvement compared to HPV negative cancers. In situ hybridization analyses proved negative. The high proportion of HPV positive breast cancers detected in this series using fresh frozen tissues cannot be dismissed, however the role of HPV in breast carcinogenesis remains unclear and may ultimately be ascertained by monitoring future breast cancer incidence amongst women vaccinated against high risk HPV types. J. Med. Virol. 83:2157–2163, 2011. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

The papillomaviruses are small, double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the Papillomaviridae-family. So far, more than 110 different HPV types have been fully characterized, and in addition, several papillomavirus types have been isolated from a number of vertebrate species [de Villiers et al., 2004]. Papillomaviruses can be grouped according to tissue tropism with HPV types found in mucosal lesion being referred to as mucosal or genital types, while HPV types found in skin are called skin or cutaneous types. Mucosal HPV types that are found preferentially in cervical and other anogenital cancers have been designated high-risk types. These high-risk HPVs have been identified as the causative agent in 99.7% or more of cervical cancers [Walboomers et al., 1999] and have also been detected in more than 50% of other anogenital cancers [zur Hausen, 1996]. The most prevalent high-risk HPV types are HPV-16 and HPV-18, which account for 70% of the cancer cases, with another 10 types making up the other 30%. These HPV types have therefore emerged as one of the most important identified risk factors for widespread human cancer [Parkin and Bray, 2006].

The putative transforming properties of high-risk HPVs are thought to primarily reside in the E6 and E7 genes that are consistently expressed in HPV-positive cancers. E6 and E7 are involved in the viral regulation of cell growth. The HPV E6 gene binds to the p53 tumor suppressor protein and targets it for ubiquitin-mediated degradation [Scheffner et al., 1990] as well as stimulating telomerase activity [Klingelhutz et al., 1996]. Loss of p53 abrogates the brake on the cell cycle when DNA damage occurs, while telomerase activity is required to stop telomere lengths shortening and cell senescence. The E7 protein targets the active, hypophosphorylated form of the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) as well as other members of the RB family [Münger et al., 1989a, b]. This results in the destabilization of pRB/E2F complexes and the release of active E2F, which allows transcription of genes required for cell cycle progression. Therefore, the over-expression of E6 and E7 allows uncontrolled cell growth without checkpoint controls and this sets the cell up for further mutations, transformation, and the formation of cancer.

Apart from cervical and anogenital malignancies, HPV has also been suggested to play a role in other cancers including squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck and more recently breast cancer. Breast cancer is the most common invasive cancer diagnosed in females in Australia and is also a leading cause of cancer death in females [NHMRC National Breast & Ovarian Cancer Centre, 2009]. Viral infection as an etiological factor in breast cancer genesis has been raised in a number of studies which have examined the role of viruses such as murine-mammary tumor virus, simian virus 40, CMV, and Epstein–Bar virus in breast cancer etiology [Lawson et al., 2001; Talbot and Crawford, 2004; Tsai et al., 2007]. These studies however have not provided consistent results with there being quite varied and sometimes contradictory outcomes. In contrast there have been some recent, more compelling, results from studies investigating a possible link between HPV and breast cancer [de Villiers et al., 2005; Kan et al., 2005; Kroupis et al., 2006]. The suspicion that HPVs could have a role in human breast cancer is based upon the in vitro evidence that the most efficient and reproducible model of human mammary epithelial cell immortalization is the expression of high-risk HPV oncogenes E6 and E7 [Dimri et al., 2005]. HPV-16 has been identified in breast tumors in Italian women and Norwegian women who had previous cervical neoplasia [Hennig et al., 1999b]. HPV-11, -16, and -18 have been identified in breast cancer in US and Brazilian women [Liu et al., 2001; Damin et al., 2004]. Additionally, HPV-33 has been identified in breast cancer in Chinese and Japanese women [Yu et al., 1999]. Recently HPV has been identified in a wide range of HPV types in cancer of the breast and nipples [de Villiers et al., 2005]. Additionally, Kan identified the presence of HPV-18 sequences in breast tumors in Australian women with 48% of the samples being HPV positive [Kan et al., 2005].

In most of these studies, where relevant analyses have been performed, no significant correlations have been observed between HPV type and tumor grade, patient survival, steroid receptor status, HER2, and p53 expression [Hennig et al., 1999a; Damin et al., 2004]. However, Kroupis et al. [2006] did show a tendency for HPV-harboring tumors to be less ER positive and to display more proliferative features as well as higher grade. Also, Hennig et al. [1999a] reported inhibited p53 expression in HPV positive breast cancer tissue. Previous studies on HPVs in normal breast tissues from healthy women who have had cosmetic surgery have yielded contradictory results, one Australian study found no HPV in normal breast tissue [Kan et al., 2005], while another did find HPV in similar samples [Heng et al., 2009].

However, the studies to date looking at the link between HPV and breast cancer have been limited in their methodologies with two deficiencies being common; (1) Many of these studies were performed on a limited number of paraffin embedded breast tumors. (2) The number of HPV types analyzed has been restricted. To circumvent these problems, this study examined fresh frozen samples from 54 breast cancer cases and used a powerful PCR-based approach that is able to identify up to 150 different HPV types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Samples

This project analyzed 54 breast cancer tissue samples and four healthy breast tissues that were removed as a part of standard surgical procedures from patients undergoing surgery at the Wesley Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia between 2003 and 2007. Fifty-eight breast tissue biopsies were obtained from 54 patients, four of which had matched healthy breast tissue. All tissue samples were confirmed by histology and the patients' median age was 57 years, with a range of 31–88 years. Data on diagnosis, location, invasive grade, histological type, menopausal status, family history of breast cancer, cervical cancer diagnosis, and HER2, estrogen, and progesterone receptors were also collected.

Tissue samples were snap frozen and stored at −80°C. Prior to extraction the samples were grinded in 1.5 ml tubes on dry ice. The tissue samples were then homogenized in Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and DNA extraction was carried out following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The DNA extracted from the breast tissue specimens was stored at −20°C until analyzed. Furthermore, paraffin-embedded tissue for in situ hybridization (ISH) was also available for all patients.

Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and this project was approved by the Princess Alexandra Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (PAH 2007/057).

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The DNA extracted tissue and blood samples were tested with PCR for HPV DNA with the general primer-pair FAP59/FAP64 [Forslund et al., 1999], and the HPV 18 type-specific primer pairs HPV18FAP59/HPV18FAP64. New type specific primers were designed for HPV-18, using the degenerate FAP primers as template. The primer sequences for these HPV-18 type specific primers were for the forward primer HPV18FAP59: 5′-TAACTGTGGGTAATCCATATT-3′ and for the reverse primer HPV18FAP64: 5′-CCAGTATCTACCATATCACCATC-3′. This primer pair yields an amplicon of 483 bp. The previously described protocol for FAP59/FAP64 was followed for the two primer pair sets as described except for the MgCl2 concentration, which was modified to 3.5 mM [Forslund et al., 1999]. Furthermore, all samples were analyzed for the presence of the human L1 sequence [Deragon et al., 1990], as a control for human DNA and as an indirect marker to ensure that a sample did not contain any PCR-inhibiting substances. Negative controls (water) were used in each batch of PCR and the negative controls were added after all the samples were added to the PCR tubes. None of the negative controls were positive. Amplified PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel containing TAE buffer and ethidium bromide (Sigma, Castle Hill, Australia). PCR amplicons were size determined under UV light using the GelDoc software (Bio-Rad, Sydney, Australia).

Cloning and Sequencing

All positive PCR products were cloned using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Samples were ligated into pCR 2.1 TOPO cloning vector and transformed into TOP10 competent cells (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's specifications. Clones with inserts were sequenced with both forward and reverse primers (BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequences were analyzed at the Australian Genome Research Facility Ltd., Brisbane. Sequences obtained were compared with available sequences in the GenBank database using the BLAST server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

In Situ Hybridization

For the ISH assay, paraffin sections from nine of the strongly HPV positive breast tumors were cut to a thickness of 5 µm and mounted on Super Frost Plus slides. One extra section per paraffin block was cut and stained with H&E and used to determine specimen quality. The high-risk HPV probe, INFORM® HPV III Family 16 Probe (B) (Roche Ventana Medical System, Tucson, Arizona) was used for the ISH assay. This HPV probe detects 16 different high-risk (cancer-causing) HPV types (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82). The ISH assay was performed according to the manufacturer's guidelines using the Discovery® XT automated system (Roche Ventana Medical System).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using online statistical software (VassarStats, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY) and associations between HPV status and various breast cancer parameters and risk factors were tested using the Chi-square test.

RESULTS

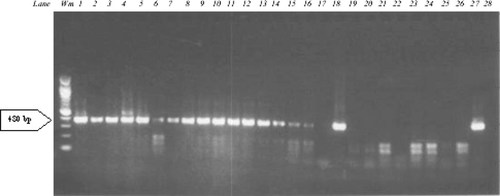

A total of 54 breast cancer specimens were analyzed in this study. A summary of the patients' characteristics and pathology features included in this study can be found in Table I. The majority of patients were post-menopausal (59%), mean tumor size was 24.3 mm, and 63% of patients were node negative. The HPV DNA prevalence in the tissues samples was 50% (27/54; Fig. 1). Sequence analyses of the positive patient samples indicated that the HPV type present was HPV-18 in all cases. The DNA sequences of the HPV-18 positive samples belonged to different strains of HPV-18. Table II provides a comparison between HPV positive and HPV negative sub-groups with respect to various patient and tumor characteristics. The age range of HPV positive patients was 31–70 years of age, with a mean of 50 years. The mean age of the group as a whole was 57 years and hence, while the age of the women with a HPV positive breast cancer tumor was slightly lower than the whole group recruited, the difference was not significant. No significant correlation was found between the HPV positive and negative sub-groups for menopausal status and family history data. Similarly for tumor grade, ER status, PR status, and HER2 status, no difference was seen between these two subgroups.

| Number | 54 patients |

| Mean age | 57.0 years (range 31–88) |

| Menopausal status | % (n) |

| Pre | 24 (13) |

| Peri | 17 (9) |

| Post | 59 (32) |

| Mean tumor size | 24.3 mm |

| Cancer type | |

| Invasive ductal | 87 (47) |

| Mixed | 2 (1) |

| DCIS | 2 (1) |

| Invasive lobular | 9 (5) |

| Grade | |

| 1 | 19 (10) |

| 2 | 42 (23) |

| 3 | 37 (20) |

| N/A | 2 (1) |

| Nodal status | |

| Negative | 63 (34) |

| Positive | 37 (20) |

| ER | |

| Positive | 80 (43) |

| Negative | 20 (11) |

| PR | |

| Positive | 72 (39) |

| Negative | 28 (15) |

| HER2 | |

| Positive | 15 (8) |

| Negative | 85 (46) |

| HPV status | |

| Positive | 50 (27) |

| Negative | 50 (27) |

Electrophoresis of 26 breast cancer samples tested with PCR using the HPV18FAP59/HPV18FAP64 primer pair. This PCR yields amplicons of 480 bp. Lanes: Wm, weight marker; Lane 1–26, breast cancer samples; Lane 27, positive PCR control (HPV-18); Lane 28 negative PCR control (no DNA).

| Characteristic | HPV positive | HPV negative | P-value (chi square) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 30–49 | 6 | 6 | |

| 50–69 | 18 | 18 | |

| >70 | 3 | 3 | 1.0 |

| Menopausal | |||

| Pre | 7 | 6 | |

| Peri | 4 | 5 | |

| Post | 16 | 16 | 0.9 |

| Family history | |||

| No | 16 | 19 | |

| Yes | 10 | 8 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Cancer type | |||

| Ductal/mixed | 26 | 23 | |

| Lobular | 1 | 4 | 0.3 |

| T stage | |||

| T1 | 19 | 11 | |

| T2 | 8 | 12 | |

| T3 | 0 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Tumor size | |||

| <25 mm | 24 | 17 | |

| >25 mm | 3 | 10 | 0.05 |

| Grade | |||

| 1 | 5 | 5 | |

| 2 | 11 | 12 | |

| 3 | 11 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Nodal status | |||

| Negative | 19 | 15 | |

| Positive | 8 | 12 | 0.4 |

| 0–3 | 26 | 22 | |

| >3 | 1 | 5 | 0.2 |

| ER status | |||

| Positive | 5 | 6 | |

| Negative | 22 | 21 | 1.0 |

| HER2 status | |||

| Positive | 4 | 4 | |

| Negative | 23 | 23 | 0.7 |

However, when tumor size was analyzed, HPV positive cancers tended to be smaller tumors. This was most markedly demonstrated when analyzed in relation to T staging which showed HPV positive tumors tending to fall into the smaller T1 and T2 groupings compared to HPV negative tumors and this was statistically significant (P = 0.03). Additionally when tumor size was assessed in terms of size being <25 or >25 mm, 89% of HPV positive cancers were <25 mm whereas only 63% of HPV negative were <25 mm (P = 0.05). Similarly, when nodal status was analyzed, HPV positive tumors were more likely to have less nodal involvement (up to three nodes), compared to HPV negative tumors.

Comparison of histological cancer types showed that of the HPV positive tumors 96.3% were of ductal or mixed origin as opposed to lobular types, compared to HPV negative tumors of which 85.2% were ductal. No correlation could be made between the two sub-groups in relation to a history of cervical cancer as this information was not reliably recorded. All 54 samples were positive for human L1, suggesting that the samples did not contain any PCR inhibitory agents.

It can be argued that the high prevalence of HPV-18 could be due to PCR contamination. However, the same person who has analyzed the breast samples have been using the same PCR (with the same PCR reagents and controls) for a skin HPV study and have never detected HPV-18 in the skin samples [Chen et al., 2008]. Also, sequencing revealed that several different strains of HPV-18 were isolated in this study.

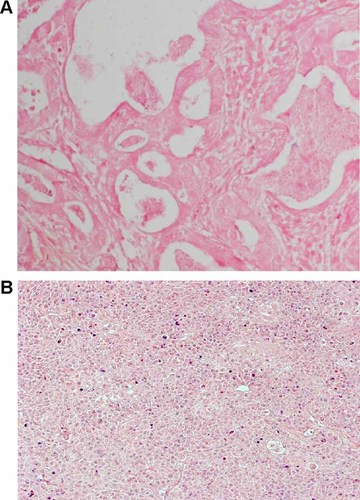

To determine whether the HPV-18 positivity was localized to the tumor tissue or stromal components, in situ hybridization analyses were performed on HPV-18 positive breast cancer tissue slides. No evidence was found of HPV-18 positivity in the breast tumor tissue or the surrounding stromal/vascular elements (Fig. 2A). In contrast, HPV-18 positive cervical cancer tissue stained positive for HPV-18 by in situ hybridization (Fig. 2B).

HPV in situ hybridization. Positive cells are stained violet. A: Breast cancer patient. B: Cervical cancer patient used as a positive control.

Three of the four normal breast tissue samples that were tested were HPV negative, while one of them was HPV-18 positive. These four normal tissue samples were taken from patients who had breast cancer and from the same breast. The patient with the HPV-18 positive normal tissue had a HPV negative breast tumor, one of the patients with a HPV negative normal tissue had a HPV-18 positive breast tumor, and two patients had both normal tissue and tumor negative for HPV DNA.

DISCUSSION

In this series 50% of fresh frozen breast cancer tissue samples were found to be positive for HPV, with HPV-18 being the only HPV type that was detected. In previous reports worldwide, HPV-16 has been the most common HPV type detected in breast cancer samples, followed by HPV-18, but other HPV types including HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, and HPV-33 have also been recorded [Hennig et al., 1999b; Damin et al., 2004; Kan et al., 2005; de Villiers et al., 2005; Heng et al., 2009]. It is interesting that in this current study performed in Brisbane, Queensland, is very similar in its results to that obtained in the only two other Australian studies, including Kan et al. [2005] who found HPV-18 only in 48% of breast cancer samples from West Australian women (Western Australia 4,000 km from current study) and Heng et al. [2009] who demonstrated very high HPV prevalence in breast cancer samples from Sydney women using in situ PCR techniques, with HPV-18 being the dominant HPV type (Sydney, New South Wales; 1,000 km from current study). It would seem that whilst HPV-18 appears to be infecting women from widely disparate locations in Australia, because of its relative isolation the HPV profile and prevalence in Australia is different compared to HPV types identified in breast cancer from women in Europe, Asia and the American continents [Damin et al., 2004; de Villiers et al., 2005; Khan et al., 2008; de Leon et al., 2009].

An unresolved issue is whether the HPV DNA found in breast cancer samples necessarily reflect active infection and whether HPV is in fact etiologically involved in tumorigenesis, rather than simply representing fortuitous or chance passage of the virus through tissues. This controversy is reflected in the recent world literature where reports of the presence of HPV in malignant tumors of the breast continue to cause debate with divergent results obtained. Whilst some studies have reported negative results [de Cremoux et al., 2008], the majority of recent studies have indicated positive detection of various HPV types, most commonly being HPV-16 and HPV-18. de Villiers et al. [2005] demonstrated that 86% of breast carcinoma samples harbored papillomavirus sequences, with the most prevalent type being HPV-11. In another study Damin et al. [2004], reported HPV DNA to be detected in 25% of breast carcinomas with the most prevalent type being HPV-16 followed by HPV-18, but none were detected in benign breast samples. HPV DNA was detected in 21% of Japanese breast carcinomas with HPV-16 being the most common type [Khan et al., 2008]. Furthermore, HPV was not found in any of the benign breast tissue specimens. Breast cancer cases from Mexico have been found to have a HPV DNA prevalence of 29%, with the most common type being HPV-16 followed by HPV-18 [de Leon et al., 2009]. In all of the above studies PCR analysis was performed on archival paraffin embedded specimens. This present study, which detected HPV-18 in 50% of cases, was performed on fresh frozen breast cancer tissue samples which could explain the higher rate of detection. The use of fresh frozen samples also minimizes the potential for handling and contamination of the tissue specimens which likely contributes to the finding of a specific HPV type present within the tumor tissue.

Superficially, it would appear that there is a lack of consensus on the prevalence and contribution of HPV to breast cancer formation. Although this current report has been able to show that 50% of fresh frozen breast cancer samples were positive for HPV-18, the level of infection of HPV-18 may be considerably less than that associated with HPV-caused cervical cancer. It is unknown whether the low level of HPV-18 presence in the breast cancer tissue is capable of transforming the cells. This could be supported by the finding of one patient with HPV-18 positive normal tissue but a HPV negative breast cancer, implying a certain magnitude of infection may be required to result in a HPV-induced cancer. A recent study has also showed that HPV-18 can be found in the nucleus of the breast cancer cells as well as in the normal breast tissue [Heng et al., 2009]. Ultimately, the contribution of HPV-18 to breast cancer development will be indicated in patients vaccinated against high-risk HPV types. Alternatively, the potential contribution of HPV-18 to breast cancer development may require sophisticated inducible transgenic mice in which HPV-18 expression can be controlled in a dose and time-dependent manner.

Of interest in this study was the fact that HPV positive tumors were statistically more likely to be early stage tumors, either T1 or T2 lesions or of a size <2.5 cm. A trend was also noted with respect to nodal status, with HPV positive tumors being more likely to be either node negative or have three or less nodes involved compared to HPV negative tumors. This could imply that the presence of HPV may at least have a fundamental role in the growth pattern and metastatic potential of breast cancers. Other reports in head and neck and lung cancers have similarly observed that the presence of HPV DNA was correlated with a better prognosis [Gillison et al., 2000; Iwamasa et al., 2000].

In this current study, HPV positive cells could not be identified with the in situ hybridization technique in a series of HPV-18 positive breast cancer tissue slides. In a previous report by de Villiers et al. [2005], in situ hybridization was able to positively identify viral sequences in the breast cancer cells for HPV-6, HPV-11, and HPV-16. The surrounding stromal tissues were negative, supporting the case for HPV having a causative effect. However the explanation for the negative in situ hybridization result here remains unclear, but could be reflective of a low viral load per positive cell or alternatively, as the PCR amplification analysis was performed in fresh frozen tissues in this study, this may be much more sensitive than in situ hybridization performed on paraffin embedded tissues. Indeed de Villiers et al. indicated that the in situ hybridization technique may be less sensitive and would not necessarily detect a single viral genome copy per cell; indeed it may be that at least 10 copies of the viral genome per cell are required for in situ detection.

The current study showed a tendency for HPV positive carcinomas to be of ductal (96.3%) rather than lobular type (compared to 85.2% HPV negative tumors), even thought this was not statistically significant. In de Villiers' report HPV was found in the nipple and areola tissues and in major ducts deep to the nipple, raising the possibility of retrograde transmission of HPV along ducts. It has therefore been postulated that if HPV were involved in carcinoma transformation that there might be a preponderance of ductal histological types [Altundag and Baptista, 2006].

Only a small number (four) of control tissue samples were included in this study, one of which was positive. However this should not significantly detract from the findings, particularly in the context of the findings of Heng et al. [2009] whose study did find HPV in a small proportion of control samples but which is consistent with the expected pathogenic requirement for HPV infection to be present in the breast tissues for some period before HPV-induced tumorogenic transformation occurs.

The potential mechanism of transmission of HPV to the breast remains unclear with opinions being divided between direct contact spread from the female perineum to the breast or hematological spread. As already indicated, the presence of HPV has been demonstrated recently not only in the primary breast cancer but also in tissue taken from the nipple regions, which suggests that HPV may enter the breast by infecting the epithelium of the nipple and areola. Additionally in two separate studies, HPV-16 was found to be present in breast tumors that occurred in European women with HPV-16 associated cervical cancer [Hennig et al., 1999b; Widschwendter et al., 2004], thus raising the possibility that HPV may be transmitted by hand from the female perineum to the breast. However recent evidence has been demonstrated for the hematological carriage of HPV on peripheral blood mononuclear cells which could provide an alternative pathway for the transmission of the virus to the breast [Bodaghi et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2009].

In conclusion, in this study of fresh frozen breast cancer samples, using a comprehensive PCR screening technique, the presence of HPV-18 only was detected in 50% of all cases. HPV positive breast cancer cases were noted to be slightly younger, and were found to be more likely smaller tumors associated with node negativity, but no other pathological correlations were noted. While in situ hybridization studies of corresponding paraffin sections were negative, and the etiological role of HPV in breast cancer remains unclear, the discovery of HPV in such a high proportion of breast cancers cannot be dismissed. Further investigation of the potential contribution of HPV-18 to breast cancer development may require research involving sophisticated inducible transgenic mice in which HPV-18 expression can be controlled in a dose and time-dependent manner. Ultimately the role of HPV in breast cancer development will be ascertained by monitoring the future incidence of the disease in women administered cervical cancer vaccinations against high-risk HPV types.

Acknowledgements

The funding bodies played no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding bodies.