Improving radiology information systems for inclusivity of transgender and gender-diverse patients: what are the problems and what are the solutions? A systematic review

Abstract

Introduction

In medical radiation science (MRS), radiology information systems (RISs) record patient information such as name, gender and birthdate. The purpose of RISs is to ensure the safety and well-being of patients by recording patient data accurately. However, not all RISs appropriately capture gender, sex or other related information of transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) patients, resulting in non-inclusive and discriminatory care. This review synthesises the research surrounding the limitations of RISs preventing inclusivity and the features required to support inclusivity and improve health outcomes.

Methods

Studies were retrieved from three electronic databases (Scopus, PubMed and Embase). A quality assessment was performed using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Research and Non-Research Evidence Appraisal Tools. A thematic analysis approach was used to synthesise the included articles.

Results

Eighteen articles were included based on the predetermined eligibility criteria. The pool of studies included in this review comprised primarily of non-research evidence and reflected the infancy of this research field and the need for further empirical evidence. The key findings of this review emphasise how current systems do not record the patient's name and pronouns appropriately, conflate sex and gender and treat sex and gender as a binary concept.

Conclusion

For current systems to facilitate inclusivity, they must implement more comprehensive information and data models incorporating sex and gender and be more flexible to accommodate the transient and fluid nature of gender. However, implementation of these recommendations is not without challenges. Additionally, further research focused on RISs is required to address the unique challenges MRS settings present to TGD patients.

Introduction

Transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) people experience significant health disparities and poor health outcomes compared with their cisgender counterparts.1 Unfortunately, medical radiation science (MRS) settings present significant discomforts for TGD patients, and radiology environments have been shown to provide less inclusive care for TGD patients compared to other medical specialties.2-4 This only further deepens health inequities, with TGD people foregoing necessary health care to avoid such negative experiences.5 Barriers to health care for TGD patients include experiences of discrimination, lack of knowledgeable providers and practitioners and unsuitable health systems.6-8

Before proceeding, the authors wish to emphasise that the terminology used in this review is based on the current recommendations of the Health Level 7 (HL7) Gender Harmony Model and the Gender, Sex and Sexual Orientation Ontology to support and champion inclusivity by using the most current and appropriate terminology.9-11 Gender refers to a person's gender identity and how they feel and perceive themselves. Sex refers to a person's assigned sex at birth (or sex assigned at birth) and is the sex recorded in birth records based on observed physical characteristics and genitalia at birth. Assigned sex at birth is the current and inclusive terminology superseding ‘biological sex’, which is considered an outdated and discriminatory term.12 A person's name to use, used name or name used refers to the name by which a patient should be addressed and displaces the outdated and non-inclusive terminology ‘preferred name’.9-11, 13 There are several umbrella terms which describe people whose gender does not align with their sex assigned at birth or who do not relate to a binary gender (i.e. male or female). For the purposes of this paper, the terms TGD are used with respect and the understanding that people may use a range of terms to best describe their gender identity and expression. Cisgender refers to people who have a gender identity aligned with their assigned sex at birth.

Health information systems enable health practitioners to record data, information and knowledge pertinent to a patient's care journey.14 Radiology information systems (RISs) and hospital information systems (HISs) are two types of health information systems used in their respective health care facilities. Health care procedures are not conducted in isolation, and information relating to each patient, such as patient identification details, should be consistent between these systems. It would also be inefficient and could introduce inaccuracies if the same data, such as the patient's name, was manually entered into each system. To combat this, RISs, HISs and other health information systems can communicate and share information via the HL7 communication standard, which has been adopted by over 90% of health care system vendors worldwide.15 HL7 is an international standards organisation concerned with ensuring consistency of information exchange between health care systems and organisations, such as by providing guidelines on how health care information and data (e.g. gender and sex) are recorded. In recent years, systems have been developed to collate information from different health care providers into a single record, known as an electronic health record (EHR), such as My Health Record in Australia.14, 16 Each specialised system, such as the RIS or HIS, forms a subset of the EHR.

The purpose of health information systems is to support practitioners in providing patient care.14 Data must be current, accurate and available. Unfortunately, for TGD patients, these systems can be a significant barrier to care and are currently inadequate to support their inclusivity.6-8, 17, 18 The limitations of these systems often result in misgendering and the use of incorrect names and pronouns by MRS practitioners, which illustrates the non-inclusive and discriminatory care received by TGD patients.19, 20 Incorrect information also has diagnostic implications, such as for protocol selection by the radiographer and image interpretation by the radiologist, and is detrimental to patient safety.3 If these systems cannot record the information they were designed to capture, they cannot fulfil their purpose of aiding practitioners to improve health outcomes, which presents a significant issue.

Recently, there has been some movement towards improving health information systems, most notably with the publication of the HL7 Gender Harmony Model in August 2021.21, 22 The HL7 Gender Harmony Model is an informative document that aims to guide the implementer community, such as RIS vendors, on how to create inclusive information systems.23 The document achieves this by defining an information model that can comprehensively capture gender, sex and related data to support inclusivity of all patients.24 However, it is still undergoing development and is yet to be considered mandatory within the HL7 communication standards.23, 25 Evidently, much more progress is needed.22, 26 McClure et al.26 states how the need for inclusive sex and gender data capture in information systems to address health inequities and improve health outcomes for TGD people has been well-known for over 30 years, coinciding with the growth of transgender activism since the 1990s.27 However, this has had a limited influence on clinical information systems, where adoption of inclusive practices has been insignificant and miniscule.

While previous reviews, such as those by Bolderston and Ralph,28 van de Venter and Hodgson29 and Hammond and Lockwood,30 investigated the influence of MRS physical environments and MRS practitioners' knowledge, behaviour and attitudes on TGD patient care, there is limited systematic research on the impact of RISs in MRS on TGD patient care. Additionally, although existing research overwhelmingly agrees that current health information systems are inadequate to support inclusivity, no existing research synthesises the limitations of current systems and the proposed solutions to these issues. This review aims to address this gap by synthesising research surrounding the current limitations of RISs used in MRS practice and what features these systems require to support the inclusivity and health outcomes of TGD patients.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

The following research questions guided this review: ‘What are the current limitations of RISs preventing inclusivity of TGD patients in MRS practice?’ and ‘How can RISs be improved to support inclusivity of TGD patients in MRS practice?’ The review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.31 Literature searches were conducted using the Scopus, PubMed and Embase databases. Controlled vocabularies were utilised where available; Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for PubMed and Emtree for Embase.

The search strategy is detailed in Table 1. Search criteria 1 was initially utilised to identify articles focused on RISs only. These initial searches returned minimal results, suggesting that radiology and MRS-specific research in this area is limited. This justifies the extended search criteria for this review, which incorporates related systems that share gender or sex information with RISs, such as HISs and EHRs. Search criteria 2 was included to identify any papers discussing these systems in the context of TGD people. Terminology to describe sex and gender is constantly evolving, and outdated and discriminatory terminology is still prevalent in literature, so a comprehensive range of terms was included.32 Related concepts, such as gender identity and dysphoria, were also included for completeness. A search comprised of search criteria 1 and 2 returned many articles irrelevant to this review. Search criteria 3 was introduced to ensure results specifically focused on how gender or sex data is captured and recorded in these systems. The final search combines these three criteria, as shown in Table 1.

| Scopus | PubMed | Embase (Ovid) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search criteria 1 | TITLE (“Radiol* Informa* System*” OR “Picture Archiv* and Comm* System*” OR “Hospital Inform* System*” OR “Health Inform* System*” OR “Medical Inform* System*” OR “Electronic Health Record*” OR “Electronic Medical Record*” OR “Health Level Seven” OR “Health Level 7” OR “HL7”) | “radiology information systems”[MeSH Terms] OR “hospital information systems”[MeSH Terms] OR “health information systems”[MeSH Terms] OR “electronic health records”[MeSH Terms] OR “medical records systems, computerized”[MeSH Terms] OR “health records, personal”[MeSH Terms] OR “medical records”[MeSH Terms] OR “health level seven”[MeSH Terms] | exp *radiology information system/ or exp *“picture archiving and communication system”/ or exp *hospital information system/ or exp *electronic health record/ or exp *electronic medical record/ or exp *medical record/ or exp *medical information system/ |

| Search criteria 2 | TITLE-ABS-KEY (transgender* OR “trans gender*” OR transpeople* OR “trans people*” OR transperson* OR “trans person*” OR transmale* OR “trans male*” OR transfemale* OR “trans female*” OR transman OR “trans man” OR transmen OR “trans men” OR transwoman OR “trans woman” OR transwomen OR “trans women” OR transboy* OR “trans boy*” OR transgirl* OR “trans girl*” OR transsexual* OR trans-sexual* OR “gender identit*” OR “gender minorit*” OR “gender nonconform*” OR “gender non-conform*” OR genderfluid* OR gender-fluid* OR “gender fluid*” OR genderexpansive OR gender-expansive OR “gender expansive” OR genderqueer* OR gender-queer* OR “gender queer*” OR gender-varian* OR “gender varian*” OR gender-divers* OR “gender divers*” OR gender-creative* OR “gender creative*” OR “gender dysphoria” OR “gender inequ*” OR nonbinary OR non-binary) | “transgender*”[All Fields] OR “trans gender*”[All Fields] OR “transpeople*”[All Fields] OR “trans people*”[All Fields] OR “transperson*”[All Fields] OR “trans person*”[All Fields] OR “transmale*”[All Fields] OR “trans male*”[All Fields] OR “transfemale*”[All Fields] OR “trans female*”[All Fields] OR “transman”[All Fields] OR “trans man”[All Fields] OR “transmen”[All Fields] OR “trans men”[All Fields] OR “transwoman”[All Fields] OR “trans woman”[All Fields] OR “transwomen”[All Fields] OR “trans women”[All Fields] OR “transboy*”[All Fields] OR “trans boy*”[All Fields] OR “transgirl*”[All Fields] OR “trans girl*”[All Fields] OR “transsexual*”[All Fields] OR “trans sexual*”[All Fields] OR “trans sexual*”[All Fields] OR “gender identit*”[All Fields] OR “gender minorit*”[All Fields] OR “gender nonconform*”[All Fields] OR “gender non conform*”[All Fields] OR “genderfluid*”[All Fields] OR “gender fluid*”[All Fields] OR “gender fluid*”[All Fields] OR “genderexpansive*”[All Fields] OR “gender expansive*”[All Fields] OR “gender expansive*”[All Fields] OR “genderqueer*”[All Fields] OR “gender queer*”[All Fields] OR “gender queer*”[All Fields] OR “gender varian*”[All Fields] OR “gender varian*”[All Fields] OR “gender divers*”[All Fields] OR “gender divers*”[All Fields] OR “gender creative*”[All Fields] OR “gender creative*”[All Fields] OR “gender dysphoria”[All Fields] OR “gender inequ*”[All Fields] OR “nonbinary”[All Fields] OR “non-binary”[All Fields] | (“transgender*” OR “trans gender*” OR “transpeople*” OR “trans people*” OR “transperson*” OR “trans person*” OR “transmale*” OR “trans male*” OR “transfemale*” OR “trans female*” OR “transman” OR “trans man” OR “transmen” OR “trans men” OR “transwoman” OR “trans woman” OR “transwomen” OR “trans women” OR “transboy*” OR “trans boy*” OR “transgirl*” OR “trans girl*” OR “transsexual*” OR “trans sexual*” OR “trans sexual*” OR “gender identit*” OR “gender minorit*” OR “gender nonconform*” OR “gender non conform*” OR “genderfluid*” OR “gender fluid*” OR “gender fluid*” OR “genderexpansive*” OR “gender expansive*” OR “gender expansive*” OR “genderqueer*” OR “gender queer*” OR “gender queer*” OR “gender varian*” OR “gender varian*” OR “gender divers*” OR “gender divers*” OR “gender creative*” OR “gender creative*” OR “gender dysphoria” OR “gender inequ*” OR “nonbinary” OR “non-binary”).af. |

| Search criteria 3 | (“collect*”[All Fields] OR “captur*”[All Fields] OR “document*”[All Fields] OR “term*”[All Fields] OR “data*”[All Fields] OR “field*”[All Fields] OR “inform*”[All Fields] OR “record*”[All Fields]) | “collect*”[All Fields] OR “captur*”[All Fields] OR “document*”[All Fields] OR “term*”[All Fields] OR “data*”[All Fields] OR “field*”[All Fields] OR “inform*”[All Fields] OR “record*”[All Fields] | (“collect*” OR “captur*” OR “document*” OR “term*” OR “data*” OR “field*” OR “inform*” OR “record*”).af. |

| Final search | Search criteria 1 AND Search criteria 2 AND Search criteria 3 | Search criteria 1 AND Search criteria 2 AND Search criteria 3 | Search criteria 1 AND Search criteria 2 AND Search criteria 3 |

| Filters | 2021–present | 2021–present | 2021–present |

| Number of results | 34 (Searched on 5 December 2023) | 51 (Searched on 5 December 2023) | 63 (Searched on 5 December 2023) |

- * denotes a wildcard operator for word variations with different suffixes. For example, document* will returns results including document, documents, documenting, documented and documentation.

- TITLE (“search term/s”) returns records containing the specified search terms in the title of the article.

- TITLE-ABS-KEY (“search term/s”) returns records containing the specified search terms in the title, abstract or keywords of the article.

- “Search term” [All Fields] returns records containing the specified search term in any field of the article database entry.

- “Search term” [MeSH Terms] returns records assigned the specified MeSH term.

- exp *“search term” returns records with the specified Emtree term and any child terms (exp) and the Emtree term or any child term must be the designated as a main topic or major focus of the article (*).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed, full-text articles published in English were included in this review, excluding conference abstracts due to their brevity and insufficient depth for analysis. Only articles investigating how RISs, HISs or EHRs captured gender or sex data or related data relevant to a person's gender or sex (e.g. name and organs) and the subsequent impacts on transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse populations were considered. Articles published prior to August 2021 were excluded, as many articles prior to this date reference outdated information concerning the HL7 Gender Harmony Model, which was first published in August 2021. The HL7 Gender Harmony Model represents a landmark document for health information systems due to the ubiquity in the uptake of the HL7 communication standards among RISs, HISs and EHRs, and it is essential that the included articles feature the most current information. Any articles that considered cisgender people only, did not mention concepts related to gender identity, were not centred on a health care setting, did not specifically consider how gender or sex data or related data relevant to a person's gender or sex is recorded, focused solely on health care practitioners' knowledge and attitudes, focused solely on the accuracy and completeness of data records or used gender or sex data to inform some other research topic (e.g. pathology or demographics) were irrelevant to this review and were excluded.

Screening

After performing the literature search, results from the three databases were imported into EndNote (Version 9.3.3) for screening and duplicate removal. Manual verification was performed to remove any remaining duplicates and articles published from January to July 2021. The remaining articles were screened by title and abstract. Subsequently, full-text articles were obtained and assessed for eligibility. Suitability for this review was assessed based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Screening was predominantly performed by one reviewer (NH), with results validated by another reviewer (AW).

Quality assessment

A quality appraisal and evidence assessment of the articles was conducted according to the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice (JHNEBP) Research and Non-Research Evidence Appraisal Tools.33 The JHNEBP tools were selected as they are among the few validated tools suitable for assessing non-research evidence, such as expert opinions, and are guided by an evidence-based practice model.33, 34 According to the JHNEBP appraisal, each article is assigned a level in the evidence hierarchy ranging from level I (highest; randomised control trials and evidence-based clinical practice guidelines) to level V (lowest; reviews, case reports and expert opinions).33 The appraisal tools provide a checklist to assess each type of article, and a grade is assigned to each article to signify its quality (A: high quality, B: good quality or C: low quality). All studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in this review, irrespective of their methodological quality, due to the developing nature of the research area and the subsequent limited body of research available. Two reviewers (NH and AW) independently appraised the articles, with any disagreements resolved in consultation with the third reviewer (ZS).

Data extraction and synthesis

Relevant information was extracted from each article, including the country of origin, type of article, included information systems and critical findings. A thematic analysis approach was used to synthesise the included articles. Each article was read thoroughly to generate and identify initial codes, which informed the thematic creation, review and definition. Data extraction was predominantly performed by one reviewer (NH), with results validated by another reviewer (AW).

Results

Study selection

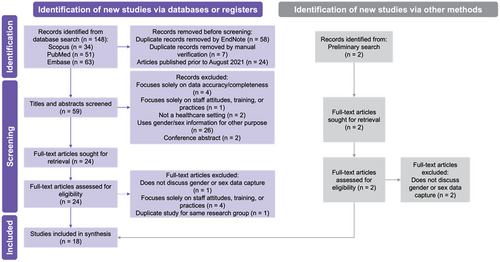

Initial searches of the three databases returned 148 records, of which 65 were duplicate entries and 24 were outside the specified publication date inclusion criteria. The remaining 59 articles were screened for title and abstract. Thirty-five of these articles were deemed unsuitable per the inclusion and exclusion criteria, leaving 24 articles for full-text screening. 18 eligible articles were identified. Examining the reference lists of eligible articles identified no additional relevant studies. Two further articles were identified during the development of the search strategy but were both excluded due to not meeting the selection criteria. This is summarised in Figure 1.

Study characteristics and results

Of the 18 studies included in this review, eight (44%) were expert opinions,35-42 five (28%) were case reports,22, 26, 43-45 three (17%) were original qualitative research studies13, 46, 47 and two (11%) were reviews.48, 49 14 of the 18 studies (78%) focused on settings in USA,13, 22, 26, 35-38, 40-42, 45, 47-49 two (11%) were focused on Canadian health care,39, 43 one (6%) was based in Argentina,44 and one (6%) surveyed system manufacturers globally.46 Regarding the information systems discussed in each of the 18 studies, 14 (78%) solely considered EHRs,13, 22, 35-42, 44, 45, 47, 48 three (17%) considered EHRs and HISs,26, 43, 49 and a single paper (6%) analysed RISs.46 The key characteristics of the included articles and the relevant findings in response to the research questions of this review are summarised in Table 2.

| Article | Country of origin | Type of article and study design | Information systems discussed | Comments on gender and sex data capture in existing systems | Proposed recommendations for gender and sex data capture | Other relevant findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albert and Delano40 | United States of America | Qualitative, expert opinion | EHRs |

|

— |

|

| Alpert et al.13 | United States of America | Qualitative, interpretive descriptive | EHRs |

|

— |

|

| Antonio et al.43 | Canada | Qualitative, case report | EHRs, HISs |

|

|

|

| Baker et al.41 | United States of America | Qualitative, expert opinion | EHRs |

|

— |

|

| Baker et al.22 | United States of America | Qualitative, case report | EHRs |

|

|

|

| Dixon and Holmes49 | United States of America | Qualitative, narrative review | EHRs, HISs |

|

|

— |

| Giraldo et al.44 | Argentina | Qualitative, case report | EHRs |

|

|

|

| Goldhammer et al.35 | United States of America | Qualitative, expert opinion | EHRs |

|

|

|

| Grasso et al.36 | United States of America | Qualitative, expert opinion | EHRs | — |

|

|

| Grutman37 | United States of America | Qualitative, expert opinion | EHRs |

|

|

— |

| Keuroghlian38 | United States of America | Qualitative, expert opinion | EHRs | — |

|

— |

| Kronk et al.48 | United States of America | Qualitative, state-of the-art review | EHRs |

|

|

|

| Marney et al.45 | United States of America | Qualitative, case report | EHRs | — |

|

|

| Matoori et al.46 | Worldwide | Qualitative, cross-sectional study | RISs, picture archiving and communication systems |

|

|

— |

| McClure et al.26 | United States of America | Qualitative, case report | EHRs, HISs |

|

|

|

| Mehta et al.47 | United States of America | Qualitative, cross-sectional study | EHRs |

|

|

|

| Queen et al.39 | Canada | Qualitative, expert opinion | EHRs |

|

|

|

| Ram et al.42 | United States of America | Qualitative, expert opinion | EHRs | — |

|

— |

Fourteen articles (78%) reported that current RISs in MRS practice and HISs and EHRs in wider health care practice inadequately capture sex and gender data and are major contributors to the non-inclusive and discriminatory health care received by TGD patients.13, 22, 26, 35, 37, 39-41, 43, 44, 46-49 The most common issues recognised in current systems were the conflation of sex and gender as a single concept, described in 10 articles (56%),13, 22, 26, 35, 39, 43, 44, 46, 47, 49 and treatment of sex and gender as binary concepts (male or female only), present in nine articles (50%).13, 22, 26, 35, 40, 41, 43, 46, 47 The limitations of current systems are summarised in Table 3.

| Limitation | Studies identifying limitation |

|---|---|

| Conflation of sex and gender | 13, 22, 26, 35, 39, 43, 44, 46, 47, 49 |

| Gender is treated as a fixed and static binary concept | 13, 22, 26, 35, 40, 41, 43, 46, 47 |

| ‘Othering’ of TGD people | 26, 41, 46, 48 |

| Inability to discriminate between a patient's used name and legal name | 13, 37, 44 |

| Use of outdated, inappropriate and discriminatory terminology | 13, 37, 39, 43, 48 |

In response to the issues identified with current systems, 14 articles (78%) proposed recommendations supporting a more comprehensive information model to support the inclusivity of TGD patients.22, 26, 35-39, 42-45, 47-49 10 articles (56%) identified the need for the information model to record each patient's name used and pronouns,26, 35-38, 43-45, 47, 48 12 articles (67%) described how systems should record both the assigned sex at birth and current gender,22, 26, 35-37, 42-48 and seven articles (39%) highlighted the importance of expanded, current and appropriate gender and sex terminology and value sets.22, 35-37, 42, 48, 49 The proposed recommendations to current systems are summarised in Table 4.

| Recommendation | Studies proposing recommendation |

|---|---|

| Record patient's name and pronouns | 26, 35–38, 43–45, 47, 48 |

| Record gender and assigned sex at birth | 22, 26, 35–37, 42–48 |

| Data fields (e.g. gender) allowing multiple options to be selected | 22, 26, 35, 37 |

| Data fields (e.g. gender) allowing free text input (not limited to only listed options in a fixed-value data set) | 26, 36, 37, 42, 44 |

| Expanded value sets with the use of appropriate and non-discriminatory terminology | 22, 35–37, 42, 48, 49 |

| Support for Indigenous populations and languages other than English | 37, 39 |

| Systems need to be flexible to allow for different use cases (e.g. patient's name in different contexts, such as in patient-practitioner interactions and for billing purposes) | 22, 26, 35, 37, 39, 45 |

| Anatomical inventories | 22, 36, 38, 43, 45 |

The literature highlighted several challenges preventing the widespread adoption of inclusive clinical systems. Eight articles (44%) described the complex requirements of implementing an inclusive gender and sex model for data collection,22, 26, 35, 37, 39, 42, 44, 45 and four articles (22%) recognised the substantial financial and technical obstacles.26, 35, 39, 43 Eight articles (44%) noted the challenge of standardisation; the interconnectedness of systems in health care means countless separate systems need to be aligned to optimise patient treatment plans, and this is particularly challenging given the vast landscape of vendors and practices supplying and designing RISs and other health information systems.22, 26, 35, 36, 39, 41, 44, 45

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of the articles is presented in Tables S1–S4. Three articles (17%) were classified as level III evidence, while 15 articles (83%) were Level V evidence. 15 articles (83%) were graded high quality, two articles (11%) were graded good quality, and one article (6%) was graded poor quality. The relatively high quality of studies reflects the experience of the researchers, many of whom are experts in this hybrid research area of TGD health and medical informatics, and the evidence-based approaches used to support the findings.

Discussion

Four recurring themes emerged from the analysis of the literature included in this review: The design of current systems is inadequate to support inclusivity of TGD patients, a comprehensive model capturing gender and sex information is required, systems need to be flexible, and there are several technical, implementation and interoperability challenges.

The design of current systems is inadequate

A common theme drawn from the synthesis of the studies is how some aspects of current information systems used in health care are disruptive and detrimental to TGD health care and health outcomes.13, 22, 26, 35, 37, 39-41, 43, 44, 46-49 Unfortunately, inadequacies in current systems are reflective of the discrimination TGD people experience not only in broader health care but also in society in general.50 All the issues to be discussed demonstrate how information systems can be a barrier to care for TGD patients.6, 48

A common issue in current systems is the conflation between sex and gender, which are separate concepts.13, 22, 26, 35, 39, 43, 44, 46, 47, 49 This issue manifests in information systems when only a single field is provided to record a patient's sex or gender. Sex is a biological characteristic reflective of a person's anatomy, chromosomes and hormones, while gender encompasses a person's gender expression and identity.40 In MRS practice, sex and gender are crucial to a patient's care journey and must be documented accurately and separately. For example, a patient with an assigned sex at birth of female and male gender identity who has not yet begun gender-affirming therapy will require considerations regarding patient care based on their gender identity (e.g. how to address the patient) and radiation safety based on their assigned sex at birth (e.g. pregnancy).

In many systems, gender is treated as a static and fixed concept, with limited options available.13, 22, 26, 35, 40, 41, 43, 46, 47 Most commonly, systems defined gender as a binary concept with male or female options only. Gender exists along a continuum, and systems that treat gender as a fixed concept limited to specific values are inherently non-inclusive to patients who do not align with any of the options presented. One particularly concerning example is systems that provide the options of ‘male’, ‘female’ or ‘other’.26, 41, 48 The use of an ‘other’ category – a literal ‘othering’ – minimises and diminishes the gender of all patients who do not align with ‘male’ or ‘female.’

Specific attention is drawn to the study by Matoori et al.,46 the only study in this review focused on RISs specifically. In this report, the authors found that most RISs had only a single data field to record sex and gender, and options were limited to ‘male’, ‘female’ or ‘other’, which is consistent with the findings of other articles in this review. However, the conclusions drawn by Matoori et al.46 are not aligned with the other studies presented in this review. Matoori et al.46 concluded that this third option – the ‘other’ category – enabled RISs to be accurate and inclusive. This is clearly mistaken because ‘othering’ is discriminatory.26, 41, 48 Additionally, while Matoori et al.46 highlighted that systems conflated sex and gender, they did not consider this as discriminatory or non-inclusive. In actuality, the data collected from vendors by Matoori et al.46 showing how RISs only have one gender or sex data field limited to three options is damning evidence that RISs are non-inclusive and discriminatory, despite their conclusions.

Transgender and gender-diverse people commonly use a name different from their legal name to affirm their gender identity.51 Addressing TGD patients by the correct name is vital to supporting the inclusivity of their gender identity, as many TGD people use a name that is different from the name present on legal documents or medical records. Many systems only have a single field to store a patient's name, which is inadequate given that a patient's name may differ from their legal name.13, 37, 44 In much the same way that reducing a patient's gender to their assigned sex at birth is discriminatory, using a patient's legal name instead of their used name can invoke assumptions of gender because a legal name is often highly gendered based on the patient's assigned sex at birth.51 Even when systems provide multiple fields for this, issues arise due to the need for different names in different settings.37 For example, RISs are often linked to other medical records, such as Medicare. A patient may update their name with a specific health practitioner on their system, but their legal name is required to process the patient for billing. To process the billing, the patient's name is overwritten, and the next time the patient presents to that practitioner, the incorrect name is used even though the patient recalls having emphasised this during their last encounter.39 This reduces the patient's trust in the health care system and, subsequently, contributes to poorer health outcomes.

Even in systems that implement some features demonstrating inclusivity, outdated, incorrect and discriminatory terminology is still prevalent.13, 37, 39, 43, 48 Terminology is constantly evolving to meet the needs of and accurately reflect TGD people. Many systems use outdated terminology, such as ‘female-to-male’ and ‘male-to-female’, which is confronting for patients given that the predominant reason for shifting terminology is the derogatory meaning, implications and assumptions associated with obsolete terminology.48 A seemingly innocuous but potentially harmful use of terminology is ‘preferred name’ or ‘chosen name’.42 This emphasis on ‘preferred’ or ‘chosen’ reduces one's name, and subsequently gender identity, to simply being an active choice and preference. It is non-inclusive because it suggests that the patient's name is merely a preference and is biased towards assuming one's ‘actual’ name is their legal name.

It is important to note that many health care practices continue to use legacy systems, which likely possess all the issues discussed.26 Using legacy systems beyond manufacturer update and support periods is commonplace.52, 53 Nevertheless, even modernised systems have some of these issues. For example, in the case report by Marney et al.45 describing upgrades made to an existing EHR system, the new system continued to use the discriminatory terminology ‘preferred’ name and pronouns. While much of their work in improving the system to include gender identity and legal sex was commendable, it is apparent that even newer systems can be fallible to these issues.26

A comprehensive model is required

Several improvements facilitating a comprehensive model for gender and sex data capture in information systems are required to promote inclusivity of TGD patients to aptly recognise the complexity and diversity of gender identity and sex.22, 26, 35-39, 42-45, 47-49 Inclusivity, in any patient interaction, begins with recognising the patient by their correct name and pronouns. Systems need to be able to accurately record each patient's used name and pronouns.26, 35-38, 43-45, 47, 48 Again, it is emphasised that the system should not be describing these fields as ‘preferred’ or ‘chosen’. Systems should, at a minimum, record both current gender and assigned sex at birth for each patient to discriminate between the concepts of gender and sex.22, 26, 35-37, 42-48 Further extensions would include fields such as sex for clinical use (e.g. the sex used for image interpretation) and recorded sex or gender (e.g. administrative or legal sex used for billing purposes). It is noteworthy to mention that Matoori et al.,46 the only study in this review solely focused on RISs, supports the recommendation that systems must record both gender and sex. Each of these fields should be supported by adequate value sets reflecting the continuum of sex and gender, and current and appropriate terminology should be used to avoid discrimination and support inclusivity.22, 35-37, 42, 48, 49

While most of the studies agree that a comprehensive model incorporating multiple data fields and expanded data sets for sex, gender and name are required, the opinion on more comprehensive information models featuring anatomical inventories is somewhat divided. Anatomical inventories are components of health records that document the presence or absence of specific organs in a patient's body.36 Many authors support the use of anatomical inventories, highlighting how their usage enables optimal care because recording a patient's assigned sex at birth and gender identity is not always sufficient.22, 36, 38, 43, 45 For example, anatomical inventories could aid in diagnosis and prevent incorrect diagnostic reports, such as a reported instance where a radiologist incorrectly stated that a woman had undergone a hysterectomy, when they instead had gender-affirming genital surgery.3 Kronk et al.48 and Queen et al.39 identify the potential benefits of anatomical inventories but highlight how there is a lack of evidence validating the proposed benefits, as well as potential privacy concerns and considerations regarding invasiveness that need to be investigated before widespread implementation. Nevertheless, anatomical inventories may have clinical benefits for MRS practice.

A comprehensive model for TGD inclusivity needs to include all TGD populations. Queen et al.39 recognise how much of the research is focused on the English language and that support for other languages is needed for systems to be truly inclusive. Additionally, the terminology used needs to consider the cultural context of the patients visiting the clinical centre.37, 39 Different terminology may be used in different regions and cultures, and obsolete terms in one community may still be commonly used in another.48 Grutman37 and Queen et al.39 discuss the specific requirement to include terminology used by Indigenous populations. For example, ‘Sistergirl’ and ‘Brotherboy’ may be terms used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians when discussing their gender.54

Systems need to be flexible

Although a comprehensive model with more data fields and data value options is a step towards inclusivity, there are still issues to consider, and systems need to be flexible to meet the various needs of TGD patients. Baker et al.22 consider a scenario where a person's gender identity encompasses multiple options, such as non-binary and female. In these cases, systems should be flexible enough to enable health practitioners to select multiple options for data fields when necessary.22, 26, 35, 37 A further extension of this suggested by multiple studies was to enable a free text option for each data field, enabling health practitioners to enter options not listed in a fixed-value data set.26, 36, 37, 42, 44 This has benefits because terminology is constantly evolving and developing, so patients may not align with the terminology prepopulated in the system. Grasso et al.36 suggest that systems should enable health practitioners to create custom data fields tailored to their practice as necessary. However, they also note how such approaches with free text and custom fields would create non-standard implementations incompatible with other health care systems. Systems must also be flexible for different use cases.22, 26, 35, 37, 39, 45 For example, RISs should prominently display the patient's name used and pronouns on displays used when interacting with the patient, such as worklists, but need to maintain the patient's legal name for other purposes, such as billing and insurance. Ultimately, systems must be flexible to comprehensively and accurately reflect gender, which can be transient, fluid and complex and is not simply a box-checking exercise.55

Technical, implementation and interoperability challenges

While a system with a flexible, comprehensive model incorporating a wealth of information is ideal, the logistics of implementing such a system, given that most systems would need to be upgraded to fulfil this need, is challenging.26, 35, 39, 43 Such implementations could create financial and technical challenges, such as data storage limitations requiring physical hardware upgrades.35 This financial hurdle is a particularly pressing concern; McClure et al.26 note that even in recent times when some vendors have developed newer and more inclusive systems, many practices retain legacy systems as there is insufficient incentive to upgrade. Another issue that presents is the need for standardisation. Systems between different health care providers need to be interoperable, and there is a plethora of different systems on the market. More concerningly, the lack of standards prior to the development of the HL7 Gender Harmony Model meant that many vendors and institutions have attempted to fulfil the needs of TGD people by creating and implementing their own systems, leading to a diverse landscape of diverging models and information systems.22, 26, 35, 39, 41, 45 There are conflicting opinions on how to proceed in light of these challenges. Goldhammer et al.35 and Giraldo et al.44 express how there must be some compromise between inclusivity and system usability and standardisation; a completely flexible system that wholeheartedly supports inclusivity would be impossible to use and standardise. On the contrary, McClure et al.26 and Grutman37 emphasise how, to progress the health care outcomes of TGD populations, priority needs to be given to cultural responsiveness towards the inclusivity of TGD people, and, at this stage, it must be accepted that there will be some logistical issues.

Current limitations and recommendations for future research

The pool of studies included in this review consists primarily of non-research evidence, such as expert opinions and case reports. Such studies lack the methodological rigour and replicability necessary for generalisability and are the major weakness and limitation of this body of literature. The frequency of non-research evidence encountered demonstrates the infancy of this research area within TGD health; it is a relatively niche field combining TGD health and medical informatics. There is a lack of empirical and research evidence to suggest whether any of the methods suggested improve TGD patient satisfaction and health outcomes, and the generalisability of results is very limited. This is what Grutman37 and Kronk et al.48 highlighted in their studies. In particular, Grutman37 states how most research has focused on the act of data collection (e.g. staff practices and attitudes), but there is little research focusing on how the actual data capture and collection in the information systems actually impacts TGD patients. For example, in the case report by Marney et al.45 documenting upgrades to an existing EHR system to improve inclusivity, reported results centred on showcasing improved data collection practices by health care staff, and Marney et al.45 specifically noted a limitation of the study was that no patient satisfaction surveys were provided to patients before and after the implementation of the modified system. Further empirical research evidence is required to demonstrate the efficacy of these proposed recommendations to justify widespread uptake and evidence-based practice.

The study characteristics demonstrate that most of the research in this area focuses on EHRs rather than specific information systems within health care, such as RISs and HISs. While much can be generalised between EHRs and RISs, especially for patient information such as sex and gender which should remain consistent between both systems, TGD patients experience unique disparities in MRS settings, so specific MRS-focused research on RISs is required to refine these specific use cases and identify any MRS-specific needs.3 For example, a challenge specific to radiology is the interoperability between RISs, which communicate via HL7, and picture archiving and communication systems used for image storage, which follow the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) standard. McClure et al.26 state that radiology reporting workflows have already been impacted due to incompatibility and data inconsistency between DICOM systems and newer information systems incorporating more complex gender and sex models. Additionally, the majority of the studies were based in the USA. Although generally applicable, more culturally appropriate research in Australia is necessary. This includes identifying appropriate terminology for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, as discussed in this review.

Conclusion

This review has found that current information systems used in MRS and health care settings have several limitations that must be addressed to facilitate inclusive health care for TGD patients. Research proposes a comprehensive information model incorporating sex and gender that provides flexibility to TGD patients and supports the diverse nature of gender identity. Despite the challenges of implementing new and improved information systems, it is paramount that the MRS profession embraces the necessary changes, not least the recommendations suggested in this review, to support the inclusivity of TGD patients. Further research should investigate the impact these system improvement initiatives have on TGD patient satisfaction and health care outcomes to justify and motivate widespread uptake of these measures if they are proven effective. Any future research must engage in proactive and meaningful consultation with TGD communities. Additionally, the need for MRS-specific research in this area must be addressed to promote improvement in MRS practice and confirm that broader health care recommendations are appropriate and applicable to RISs in MRS settings.

Con?ict of Interest

The authors have no con?icts of interest to declare.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.