Palliative care in cancer: managing patients’ expectations

Abstract

Advanced cancer patients commonly have misunderstandings about the intentions of treatment and their overall prognosis. Several studies have shown that large numbers of patients receiving palliative radiation or chemotherapy hold unrealistic hopes of their cancer being cured by such therapies, which can affect their ability to make well-informed decisions about treatment options. This review aimed to explore this discrepancy between patients’ and physicians’ expectations by investigating three primary issues: (1) the factors associated with patients developing unrealistic expectations; (2) the implications of having unrealistic hopes and the effects of raising patients’ awareness about prognosis; and (3) patients’ and caregivers’ perspective on disclosure and their preferences for communication styles. Relevant studies were identified by searching electronic databases including Pubmed, EMBASE and ScienceDirect using multiple combinations of keywords, which yielded a total of 65 articles meeting the inclusion criteria. The discrepancy between patients’ and doctors’ expectations was associated with many factors including doctors’ reluctance to disclose terminal prognoses and patients’ ability to understand or accept such information. The majority of patients and caregivers expressed a desire for detailed prognostic information; however, varied responses have been reported on the preferred style of conveying such information. Communication styles have profound effects on patients’ experience and treatment choices. Patients’ views on disclosure are influenced by many cultural, psychological and illness-related factors, therefore individuals’ needs must be considered when conveying prognostic information. More research is needed to identify communication barriers and the interventions that could be used to increase patients’ satisfaction with palliative care.

Introduction

Palliative cancer treatments including radiation therapy and chemotherapy play a major role in improving quality of life in patients with advanced cancer by controlling symptoms and relieving pain. Whilst providing prolonged disease control with many current techniques, they don't, however, offer a cure for the disease”.1 Considerable evidence suggests that patients receiving palliative therapies commonly have misunderstandings about their prognosis,2 intentions of such treatments3 and they hold unrealistic hopes of their cancer being cured.4, 5 In the United States, Nationwide study conducted by Weeks et al.6 among 1193 patients receiving chemotherapy for stage IV cancers, 69% of patients with lung cancer and 81% of those with colorectal cancer did not understand that their treatment was not at all likely to cure their cancer. Another study looked into the expectations of patients with incurable lung cancer from palliative radiation therapy, and found that 64% did not report understanding that the treatment was not at all likely to cure them.7 This study also found that 92% of patients with inaccurate beliefs about radiation therapy also had inaccurate beliefs about chemotherapy, indicating that this gap in patients’ understating exists for multiple treatment modalities and provider types.

Without fully understanding their prognosis and the limitations of treatment, patients cannot make well-informed decisions about treatment choices and end-of-life care. Patients who overestimate their prognosis are more likely to pursue aggressive treatments near their end of life.8 Such therapies can result in reduced quality of life,9 significant financial costs,10 and an additional burden on the patient and their family,11 particularly in the case of radiation therapy where daily visits for treatment are required.

A number of studies have also indicated that many cancer patients have unmet communication needs when it comes to discussing their prognosis and treatment goals. For example, Lobb et al.12 conducted a study to determine patients’ needs for information and emotional support after receiving treatments for haematological malignancies, 59% of patients reported that they would have liked to discuss their experience with diagnosis and treatment with a health care professional. In addition, a literature review looking into the communication goals and needs of cancer patients concluded that patients continue to have unmet communication needs, especially those related to their psychological concerns and preferred degree of involvement in decision-making.13

This review aimed to investigate the discrepancy between physicians’ and patients’ expectations from palliative treatments by attempting to answer three main research questions:

- What are the factors associated with the development of patients’ unrealistic expectations from palliative therapies?

- Why is complete disclosure important and how does it affect patients’ mental/psychological wellbeing?

- What are patients’ and caregivers’ preferences for receiving prognostic information?

Method

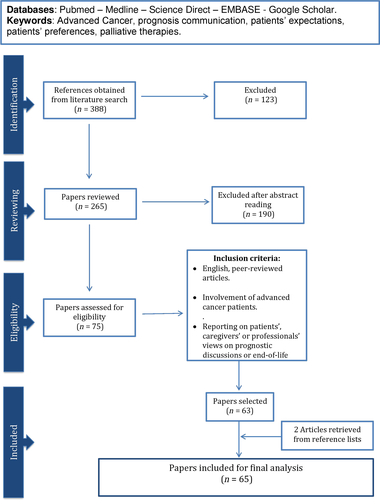

A search of databases including Pubmed, Medline, Science Direct, EMBASE and Google Scholar was carried out in October 2014, with no restrictions applied on papers’ publication date. Various combinations of relevant terms and keywords were used to ensure a complete search of current literature, such keywords included but were not limited to “advanced Cancer”, “communication of prognosis”, “patients’ expectations”, “patients’ preferences”, “palliative therapies”, “end-of-life discussions”. The eligibility criteria for this review included English, peer-reviewed articles that involve advanced cancer patients, and address how they perceive prognostic discussions or end-of-life care. Studies describing caregivers’ or health professionals’ views on such issues were also included. In addition, selected papers were reviewed for significant references in order to include any studies that had been missed during the search. Figure 1 below includes a flow diagram summarising the search process and inclusion criteria used for the purpose of this review.

Results

The literature search returned 388 articles including randomised control trials, cohort studies, retrospective studies, systematic reviews and one ethnographic study. About 123 papers were initially excluded upon reading the title, and the remaining papers were selected for further exploration and assessment. This was done by reading the abstract of each article, reviewing its content and then determining which studies meet the inclusion criteria discussed earlier. A total of 65 articles met the inclusion criteria and provided both qualitative and quantitative data, which were then analysed and categorised into themes corresponding with the specific aims of this review. All these studies are listed in Tables 1-4, with a brief summary outlining the purpose, methods and findings of each one.

| Author | Country | Population | Purpose | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Robinson et al.2 2008 |

US | 141 advanced cancer patients. | Identify communication factors influencing patients’ views about their cure. | Analysed 141 audio-recorded encounters between oncologists and patients. | Patients with advanced cancer are often more optimistic about their prognosis than their physicians. Pessimistic statements made by oncologists, regarding prognosis, were associated with fewer patients retaining false beliefs about cure. |

|

Sapir et al.3 2000 |

IL | 103 cancer patients. | Evaluate patients’ knowledge about their diagnosis/stage and their expectations of health care providers. | Structured interviews conducted with each patient. | Patients tended to underestimate the status of their illness. 36% of those with progressive disease believed their cancer was in remission. |

|

Chow et al.4 2001 |

CA | 60 advanced cancer patients. | Investigate patients’ understanding/expectations of palliative radiotherapy. | Participants completed a survey prior to their initial consultation. | 35% believed their cancer was curable, 20% expected palliative radiotherapy to cure their cancer and 38% believed it would prolong their lives. |

|

Temel et al.5 2011 |

US | 151 patients newly diagnosed with metastatic NSCLC. | Explore perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy and examine how early palliative care can affect these views over time. | Participants completed baseline and longitudinal assessments of their views over 6-months. | 33% reported that their cancer was curable at baseline, and 96% believed the goal of therapy is getting rid of all of the cancer. Patients who reported an accurate perception of their prognosis were less likely to receive intravenous chemotherapy near the end of life (P = 0.02). |

|

Weeks et al.6 2012 |

UK | 1193 patients receiving chemotherapy for stage IV lung or colorectal cancers. | Investigate prevalence of the expectation that chemotherapy could be curative and identify the factors associated with this expectation. | Patients were surveyed, and a comprehensive review of their medical records was done. |

69% lung, 81% colorectal cancer patients did not understand that their treatment was not at all likely to cure their cancer. Inaccurate beliefs were higher among patients with colorectal cancer, those who are non-white or Hispanic, and those who rated their communication with physicians very favourably. |

|

Chen et al.7 2013 |

US | 384 patients receiving radiation therapy for incurable lung cancer. | Investigate patients’ expectation from palliative radiation. | Participants completed surveys. | 64% did not understand that radiation was not at all likely to cure them. 92% of those also had misunderstandings about chemotherapy. 78% believed radiation was very or somewhat likely to help them live longer. Older and non-white patients were more likely to have inaccurate beliefs. |

- US, United States; IL, Israel; CA, Canada; UK, United Kingdom; NSCLC, Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma.

| Authors | Country | Population | Purpose | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

McGrath et al.14 2007 |

AU | 10 relatives/caregivers of dying cancer patients. | Investigate patients’ and caregivers’ awareness of terminal illness and prognosis. | Interviews and qualitative analysis. | The incurable status of the disease and the prognosis were not openly discussed with the patients or caregivers. |

|

Chan et al.15 1997 |

AU | 130 patients with advanced malignancy. | Assess how patients perceived information given by physicians and the level of such communication. | Subjects completed surveys. | About 10% were unaware of their diagnosis. Of those who knew their diagnosis, 25% stated that the diagnosis was not disclosed in a clear or caring manner. 33% had incomplete or overestimated understanding of their prognosis. Physicians were reluctant to disclose information about prognosis, especially when it is poor. |

|

Elizabeth et al.16 2001 |

US | 258 physicians and 326 patients with terminal cancers. | Determine if physicians’ behaviour contributes to the disparity between patients’ and physicians’ prognostic expectations. | Prospective cohort study in which physicians formulated survival estimates and also indicated the estimates communicated to patients. |

When requested, physicians favoured giving a frank disclosure 37% of the time, knowingly gave overestimated/underestimated estimates to 40.3% of patients, while favouring no disclosure to 22.7% of patients. Older patients were more likely to receive frank survival estimates. Experienced physicians and those who were least confident about their prognoses were more likely to favour no disclosure. The median actual survival was 26 days, the median formulated survival was 75 days and the median communicated survival was 90 days. |

|

Gordon et al.17 2003 |

US | 14 oncologists. | Understand oncologists’ attitudes about disclosing prognostic information to cancer patients with advanced disease. | Oncologists participated in interviews and focus groups. | Most physicians associated reluctance with fear of causing distress, destroying hope or compromising the patient–doctor relationship. Other challenges include considering obligation to patient's autonomy, while deciding what information needs to be given and how to communicate it to the patient. |

|

Butow et al.18 2002 |

AU | 17 patients and 13 health professionals. | Obtain patients’ and health professional views on optimal ways of presenting prognosis to patients with metastatic breast cancer. | Subjects participated in structured interviews, which were audiotaped and transcribed. | Doctors and health professionals were aware of the need to tailor information according to each patient's case. Physicians sometimes find it difficult to convey such information in a manner that is realistic, but also preserves hope. Another difficulty is the need to cater for both patients’ and family members’ needs. |

|

Kodish et al.19 1995 |

US | Analysis of a court case Arato versus Avedon. | Discuss the importance of balancing honesty and provision of hope. | The article reviewed the facts and implications of the case, and discussed the role of hope in medicine. | Reluctance could be related to a desire to foster hope, or to a discomfort with putting odds on longevity, recurrence, and cure. |

|

Anderlik et al.20 2002 |

US | 122 doctors. | Identify reasons associated with doctors withholding information. | Subjects participated in questionnaires. | The top five reasons for withholding information: sensitivity to patients’/families’ cultural norms; patient's fragile emotional state; respect for the patient's expressed wishes; concern that information would destroy hope; and respect for family's expressed wishes. |

|

Baile et al.21 2002 |

US | 167 oncologists attending an international conference. | Examine the attitudes and practices of oncologists in disclosure of bad news to cancer patients. | Participants completed a questionnaire. | 40% reported that they occasionally to almost always withhold information when requested by the family. Oncologists from Western countries were significantly less likely to comply with family requests (P < 0.001). It is even more challenging when attempting to meet the needs of family members. |

|

Clayton et al.22 2005 |

AU | 19 advanced cancer patients, 24 caregivers and 22 health professionals. | Determine the needs of terminally ill patients, and their caregivers, for prognostic information. | Audiotaped and transcribed focus groups and Individual interviews. | A desire to restrict the patient's access to information by the caregiver or vice versa was reported by professionals to be one of the most challenging aspects of discussing prognosis and end-of-life issues. Requests to withhold information are commonly, but not always, received from family members who are from non-Western cultures. |

|

The et al.23 2001 |

NL | 35 lung cancer patients. | Explore the factors that result in false optimism about recovery in patients with small-cell-lung cancer. | Qualitative observation (Ethnography) conducted over 4 years. |

False optimism usually developed during the first course of chemotherapy, and was most prevalent when cancer could not be seen on X-ray images. Optimism tended to vanish when the tumour recurred. Both physicians and patients “colluded” in refocusing attention on the treatment schedule and ignoring the long-term trajectory of the illness, which ultimately led patients to develop false optimism about their recovery. Patients may misinterpret ambiguities. |

|

Gattellari et al.24 1992 |

AU | 244 cancer patients. | Document the prevalence of misunderstandings in cancer patients, and investigate if denial is related to misunderstanding. | Subjects completed a survey assessing levels of understanding and denial. |

Identified denial as a significant predictor of patients holding inaccurate beliefs about their prognosis and goals of treatments. Patients’ ratings of the clarity of information received were also predictive of understanding. |

|

Lee et al.25 2010 |

US | 169 surrogate decision-makers for intensive care unit patients. | Assess whether numeric or qualitative statements are more reliable in conveying prognostic estimates; and whether surrogates believe physicians’ estimates. | Subjects were randomised to view one of 2 versions of a video showing a simulated family conference with a hypothetical patient. | No difference in surrogates’ understanding when conveying prognostic information using numerical or qualitatively methods. One in five surrogates overestimated patients’ prognosis by more than 20%. Many surrogates do not view physicians’ prognostications as absolutely accurate. Factors other than ineffective communication may contribute to physician-surrogate discordance about prognosis. |

|

Davey et al.26 2003 |

AU | 26 cancer patients. | Assess patients’ understanding of statistical information; and their preferences for framing, content and presentation. | Questionnaire and personal interviews. |

The majority of the patients did not understand terms such as “medial survival” and “relative/absolute survival. Most patient preferred information to be framed clearly and positively. |

|

Lobb et al.27 1999 |

AU | 100 women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. | Determine how much patients understand prognostic information, and their preferences on how to present this information. | Self-administered written questionnaire. | Many did not fully understand the language typically used by surgeons and cancer specialists: 53% could not calculate risk reduction relative to absolute risk; 73% did not understand the term “median” survival. |

|

Gaston et al.28 2005 |

AU | Systematic review. | Investigate decision-making and information provision in patients with advanced cancer. | Studies of interventions to improve information giving and encourage participation in decision-making were reviewed. | Most patients expressed a desire for full information and about two-thirds wished to actively participate in decision-making. Doctors may overestimate patients’ understanding of information. Some interventions including question prompt sheets, audio-recorded consultations and decision aids may help facilitate involvement. |

|

Chochinov et al.29 2000 |

CA | 200 terminally ill cancer patients. | Rate patients on their level of awareness of their prognosis. | Semi-structured interviews. | Depression was about three times greater among patients who did not know their prognosis (P = 0.029). Male, older patients and those with “intense social contact” reported lower prognostic awareness. Low awareness was more common among patients with underlying psychological distress and emotional turmoil. About 10% chose not to believe in their terminal status and shortened life expectancy. |

|

Mackillop et al.30 1988 |

CA | 98 cancer patients undergoing treatment. | Determine how patients perceive their illness, and how their perceptions compare with those of their attending physicians. | Semi-structured and videotaped Interviews. | Third of patients receiving palliative therapy believed their treatment to be curative, 80% of these patients significantly overestimated the likelihood of the treatment prolonging their lives. Patients with lower education levels were significantly more likely to underestimate the seriousness of their condition. Doctors frequently failed to recognise their patients’ misconceptions. |

|

Haidet et al.31 1998 |

US | 520 patients with colorectal cancer with liver metastases. | Assess decision-making in patients, and examine how communication affects patients’ understanding of prognosis and physicians’ understanding of patients’ treatment preferences. | A prospective cohort study, patient interviews and chart reviews done at study entry; patients were interviewed again after 2 and 6 months. | The substantial misunderstanding between patients and their physicians about prognosis and treatment preferences appears not to be improved by direct communication. |

|

Dunn et al.32 1993 |

AU | 142 cancer patients. | Compare the use of recorded consultations and audiotapes containing general information on patients’ satisfaction, psychological adjustment, and recall of information. | Subjects were randomised to receive an audiotape of their consultation, an audiotape about cancer in general or no tape. Structured interview used to assess recall of information. |

Satisfaction was highest in patients who received the consultation tape. The consultation tape did not improve recall, and the general tape caused a decrease in total recall of information. Audiotapes show little effects in improving patients’ recall of information. |

|

Leighl et al.33 2008 |

CA | 20 patients with metastatic NSCLC. | Evaluate the effects of a decision aid tool on understanding and anxiety. | Developed a decision-aid tool to better inform patients about prognosis and treatment options. |

Despite the enhanced understanding of potential outcomes and toxicities of therapies, many patients retained unrealistic hopes of their cancer being curable. Anxiety slightly decreased from baseline. (P < 0.04). |

|

Vos et al.34 2007 |

NL | A review study of denial in cancer patients. | Clarify the variety of concepts and the impact of denial on clinical oncology practice. | Explored denial in terms of prevalence, function, background characteristics, and pattern over time. | Denial of diagnosis varied from 4% to 47%, and denial of impact of cancer occurred in 8% to 70% of patients. Cultural backgrounds influenced prevalence of denial. A gradual decrease in denial was observed over the course the illness. |

- AU, Australia; US, United States; NL, Netherlands; CA, Canada; NSCLC, Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma.

| Authors | Country | Population | Purpose | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Matsuyama et al.8 2006 |

US | Literature review. | Determine the available sources of knowledge, choices, patients’ concerns, and how they balanced competing issues. | A literature search for studies published between 1980 and 2005 addressing: decision-making, palliative chemotherapy, prognosis communication and patients’ expectations. |

Many patients would choose undergoing aggressive chemotherapy even for small benefits. Adverse effects are less of a concern for patients than for their health care providers. Patients who overestimate their prognosis are more likely to pursue aggressive treatments near their end of life. |

|

Weeks et al.9 1998 |

US | 917 patients hospitalised with stage III or IV cancer. | Test whether or not an accurate understanding of prognosis is associated with patients preferring therapy that focuses on comfort rather than prolonging life. | Measured the proportion of patients, who prefer life-extending therapy to palliative care, and compared patients’ and physicians’ estimates of the probability of 6-month survival to actual 6-month survival. Data gathered prospectively by chart reviews, and interviewing patient, surrogates and physicians. |

Advanced cancer patients’ views on their survival can influence their treatment choices. Patients who expected a 6-month survival were 2.6 times more likely to pursue aggressive anticancer therapies instead of palliative treatments. These patients had the same survival as others who received palliative care, but were more likely to be readmitted to hospitals, undergo attempted resuscitation or die during ventilator support. |

|

Zhang et al.10 2009 |

US | 627 advanced cancer patients. | Examine the effects of end-of-life discussions on patients’ use of health-care, and assess the ability of expensive life-sustaining treatments to improve quality of life. | Longitudinal, multi-institutional study; patients were interviewed at baseline and followed through death. |

End-of-life discussions significantly reduced health care expenses on patients during their last week of life. Aggressive therapies with higher costs were associated with lower quality of death. |

|

Hancock et al.11 2007 |

AU | Systematic review. | Explore the views of patients and health professionals on disclosing terminal cancers. | 46 studies addressing truth-telling in disclosing prognosis to advanced and life-limiting cancer patients. |

Most health professionals agreed on the patients’ and caregivers’ right to know the truth about their prognosis, however, in practice, this is may be avoided for a variety of reasons. Patients can discuss end-of-life issues without increasing anxiety levels. Avoiding such discussions can result is patients receiving burdensome treatments and having less time to prepare for death. |

|

Brown et al.35 2012 |

AU | 683 breast cancer patients from 62 oncologists in five different countries. | Investigate how patients’ preferences to be involved in decision-making change before and after first consultation. | Subjects answered questionnaires, before and after consultations. |

Before consultations the majority preferred shared or patient-directed decision-making, after consultation, 43% of patients’ preferences changed, mostly towards patient-directed decision. Most early-stage breast cancer patients approach treatment decisions with a desire for decisional control. |

|

Lidz et al.36 1988 |

US | Literature review. | Describe two ways in which informed consent can be implemented. | Evaluated evidence associated with each of the two methods. | Informed consent is more beneficial when integrated into a continuing physician-patient dialogue, that forms a consistent part of diagnose and treatment. |

|

Slevin et al.37 1990 |

UK | 100 patients, 100 matched controls, 60 oncologist, 88 RTs, 790 GPs and 303 nurses. | Compare responses of cancer patients with those of cancer specialists, general practitioners and nurses in assessing personal cost-benefit of chemotherapy. | Qualitative date gathered through questionnaires. | Many patients are willing to accept treatments with major toxicities for minimal increase in overall survival. Cancer patients are much more willing to undergo radical treatments with minimal benefits compared to those who don't have cancer. |

|

Mack et al.38 2012 |

US | Literature review. | Assess the validity of reasons given by health professional for not discussing poor prognoses. | Included several studies addressing the effects of disclosing poor prognoses. |

Many underlying misconceptions found among health professionals. Evidence do not support that disclosing prognostic information can increased anxiety and depression or destroy patients’ hope. Patients may be disadvantaged by not being fully aware of prognosis. |

|

Tattersall et al.39 2002 |

AU | 118 patients with incurable cancer presenting for their initial consultation. | Assess the extent to which patients are aware of their prognosis and involved in decision-making. | Consultations were audiotaped to assess disclosure of necessary information. Patients’ recall, satisfaction and anxiety were assessed using questionnaires and interviews. | Most patients were informed about the aims of treatment (84.7%), that their disease was incurable (74.6%) and about life expectancy (57.6%). However, patient’ understanding was checked in only 10% of consultations. Being more aware of prognosis was not associated with higher levels of anxiety. |

|

Enzinger et al.40 2015 |

US | 590 patients with metastatic cancer. | Determine how prognostic discussions influence patients’ perceptions of survival, anxiety and patient–doctor relationship. | Patients completed surveys and were followed up to death. | Adjusted analyses showed no association between prognostic disclosure and increased levels of sadness, anxiety or compromising the patient–doctor relationship. |

|

Schofield et al.41 2003 |

AU | 131 patients recently diagnosed with melanoma. | Determine communication strategies that would optimise patients’ responses to receiving a melanoma diagnosis. | Patients were surveyed three times over the course of 13 months. | Anxiety levels were reduced when patients were: prepared for diagnosis of cancer, with someone close to them when hearing diagnosis, given as much information as needed, provided with written information and when their questions were discussed on the same day. |

|

Wright et al.42 2008 |

US | 332 terminally ill cancer patients. | Determine if end-of-life discussions are associated with fewer aggressive interventions. | Multi-site, prospective, longitudinal cohort study of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers. | Prognostic discussions were associated with lower rates of ventilation, resuscitation and earlier hospice enrolment. Aggressive therapies were associated with reduced quality of life and higher risk of depression. |

|

Smith et al.43 2010 |

US | 27 advanced cancer patients about to receive chemotherapy. | Determine how increasing prognostic awareness using a decision-aid tool can affect hope. | Patients were given printed estimates of treatment effects and the chance of survival. Hope was measured using the Herth Hope Index. | Hope was maintained even after honest discussions that informed patients about having a poor prognosis or low chance of survival. |

|

Mack et al.44 2007 |

US | 194 parents and physicians of children with cancer. | Investigate the relationship between parental recall of prognostic information and hope, distress and trust. | A cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study. |

Parents who received more prognostic information were more likely to report communication-related hope, even when prognosis was poor. Prognostic discussions with physicians can support hope even with a poor prognosis. |

|

Hottensen et al.45 2010 |

US | Case study report. | Determine how the style of prognostic discussions can affect the anticipatory grief experienced by terminal cancer patients and their loved ones. | Reporting of a patient case study about a 57-year old married woman recently diagnosed with local advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. | Establishing a supportive dialogue in a safe and open environment can help patients and their loved ones to understand that their feelings are natural, assist them to develop coping strategies and focus their hope on realistic goals. |

|

Yoshida et al.46 2012 |

JP | 60 family members of cancer patients. | Assess the pros and cons of prognostic discussions from the family's point of view. | Qualitative data collected through recorded, face-to-face, semi-structured interviews. | Prognostic discussions may generate some psychological distress, but also help patient achieve a more meaningful end-of-life and help family members prepare for the future mentally and practically. |

|

Heyland et al.47 2009 |

CA | 440 patients and 160 family members. | Assess the influence of prognostic discussions on patients’ and families’ satisfaction with end-of-life care. | 5-domain questionnaires were given to participants to assess their satisfaction. | Family members who recalled prognostic discussions reported significantly higher satisfaction with end-of-life care. (P = 0.03). |

- US, United States; AU, Australia; UK, United Kingdom; JP, Japan; CA, Canada; RT; Radiation Therapist; GP; General Practitioner.

| Authors | Country | Population | Purpose | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lobb et al.12 2009 |

AU | 66 cancer patients. | Determine patients’ information and emotional support needs after completing treatment. | Self-reporting questionnaires mailed to participant. |

The most commonly endorsed patients’ needs were related to co-ordination of health care services and the help to manage fear of recurrences. Almost two-thirds of participants stated that they would have liked to discuss their diagnosis and treatment plan with a health care professional. |

|

Hack et al.13 2005 |

CA | Literature review. | Explore cancer patients’ communication goals and needs. | Critique of empirical studies addressing the topic from 1992 until 2004. | Patients continue to have unfulfilled needs for disease and treatment related information. Communication outcomes are improved when physicians attend to patients’ emotional needs. Due to deficiencies in research methods and design, it is currently difficult to determine the true extent to which patients are satisfied with communication. |

|

Jenkins et al.48 2001 |

UK | 2331 heterogeneous sample of cancer patients. | Investigate patients’ preferences for prognostic information. | Data collected using an adaptation of Cassileth's Information Needs Survey. | 87% wanted all possible information, both good and bad news, 98% wanted to know if their illness was cancer. Variations of preferences were influenced by age and sex, but not by tumour site or treatment aims. |

|

Hagerty et al.49 2004 |

AU | 126 recently diagnosed with incurable cancer. | Determine preferences for communication of prognosis in patients with metastatic cancer. | Patients completed a survey to express their preferences for prognostic information, including type, quantity, mode, and timing. |

More than 95% of patients wanted information about side effects, symptoms, and treatment options. 85% wanted to know longest survival time with treatment. Words and numbers were preferred over pie charts or graphs. 59% wanted to discuss expected survival when first diagnosed, and 38% wanted to negotiate the timing of such discussion. 34 and 40% wanted to be asked about when they prefer discussing expected survival and dying, respectively. Only 11% never wanted to discuss dying/palliative care and 10% were unsure. |

|

Fried et al.50 2003 |

US | 214 patients with a life-limiting illness, along with their caregivers and clinicians. | Assess the agreement between patients, caregivers, and clinicians on prognosis discussions, and to examine patients’ and caregivers’ desire for prognostic information. | Cross-sectional surveys. |

46% of patients and 34% of caregivers did not agree that the clinician had said that the patient could die for the underlying illness. 83% of those who believed they had 1 year or less to live and 79% of those who believed they had 1 to 2 years wanted to discuss prognosis. 55% of patients and 75% and their caregivers who were interviewed retrospectively, reported that they would like to have discussed life expectancy with their physician. |

|

Delvecchio et al.51 1990 |

US | 51 oncologists. | Examine practices among American oncologists in terms of disclosing prognosis and providing hope. | Qualitative date collected through interviews and surveys. | Physicians’ practices tend to draw from distinctive cultural notions associated with hope, truth telling, doctor–patient relationship and the relationship between patient's health and mental state. Oncologists sometimes find it difficult to convey information in a realistic manner while also preserving patients’ hope. |

|

Goldstein et al.52 2002 |

AU | 58 cancer patients with Greek heritage. | Examine the range of attitudes towards prognostic information. | 8 focus groups and 8 interviews were conducted by a bilingual facilitator. | Views of the Greek community on cancer were different to what is currently considered good practice by Australian physicians. |

|

Blackhall et al.53 1995 |

US | 800 patients aged 65 years or older. | Compare views on prognostic disclosure among 4 ethnic groups: Europeans, African-American, Koreans and Mexicans. | Multi-centred surveys. | Koreans (35%) and Mexicans (48%) were less likely than African Americans (63%) and Europeans (69%) to believe that patients should be told about a terminal prognosis, and less likely to believe that the patient should make decisions about the use of life-supporting technology. When disclosing information, physicians need to take into account patients’ own personal views on disclosure. |

|

Kaplowitz et al.54 2002 |

US | 352 cancer patients. | Determine how often cancer patients want, request and receive qualitative and quantitative estimates of survival. | Subjects received surveys in mail to express their preferences and also to measure their social and psychological characteristics. |

More than 40% of those who wanted qualitative or quantitative estimates failed to ask for it. Level of education had little or no influence on patients’ preferences. Older patients and those with higher anxiety scores were significantly less likely to request prognostic information, and having a poorer prognosis was also predictive of patients wanting less information. |

|

Lobb et al.55 2001 |

AU | 100 women with early-stage breast cancer. | Determine women's preferences for discussing prognosis. | Qualitative data collected through surveys. | 91% wanted to know prognosis before starting therapy. Most patients wanted the information summarised (94%) supported by published information (88%). 80% wanted additional sources for information and emotional support. |

|

Degner et al.56 1997 |

CA | 1012 women diagnosed with breast cancer. | Determine how many women with breast cancer want to be involved in decision-making. | Cross-sectional survey assessing preferences for degree of involvement. | 66% wanted some control when choosing cancer treatments. Only 42% were satisfied with the level of control they were given during decision-making. |

|

Iconomou et al.57 2002 |

GR | 100 patients scheduled for chemotherapy. | Assess information needs of Greek cancer patients. | Interviews to assess needs for information, satisfaction, distress and quality of life. | Increased awareness was not associated with increased satisfaction, distress or quality of life. |

|

Tamburini et al.58 2003 |

IT | 182 hospitalised cancer patient. | Evaluate patients’ needs during hospitalisation. | Quantitative questionnaires and qualitative interviews. | Most expressed needs include the need for information about diagnosis and future conditions. Qualitative analysis showed that most expressed a need to know how their future will be affected rather than the actual prognosis. |

|

Pronzato et al.59 1994 |

IT | 100 patients with advanced cancer. | Evaluate awareness of diagnosis, prognosis and goals of palliative therapy. | Face-to-face interviews. | No patient had a correct idea of the poor prognosis of the disease. Only 11.5% of those receiving chemotherapy knew the palliative intent of treatment. Only a minority of patients expressed dissatisfaction with the information received; it seems very common to withhold information from patients in Italy. |

|

Miyata et al.60 2005 |

JP | 427 members of the general public aged (20–50) years old. | Investigate views of the general public on disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis of cancer. | A cross-sectional, stratified random sample of the general public completed a survey received in the mail. | While the majority (86.1%) preferred full disclosure about diagnosis, around 64% wanted only partial disclosure about prospects of full recovery and expected length of survival. |

|

Huang et al.61 1999 |

AU | 36 cancer patients and 12 relatives born in China, Singapore and Malaysia. | Assess the attitudes and information needs of migrant patients and their relatives. | Qualitative data collected through four focus groups and 26 phone interviews. | More patients preferred non-disclosure of a poor prognosis, and many emphasised the role of family in liaising between health providers and the patient. |

|

Alijubran62 2010 |

SA | Review article. | Explore the factors influencing the public attitude towards disclosure of cancer in Saudi Arabia. | Data collected from local surveys conducted among doctors, patients and the general public. | Public attitude is still conservative towards full disclosure. Saudi physicians need to establish a good rapport with the family as well as with the patient; more often the family would want to know first, and they are strongly involved in the decision-making process. |

|

Qasem et al.63 2002 |

KW | 217 physicians practicing in Kuwait. | Examine preferences of physicians for disclosure of cancer in Kuwait. | A cross-sectional survey conducted in public hospitals. | While 67% preferred full disclosure of diagnosis, 79% would withhold the truth if asked by a family member. Withholding information was more common among physicians who had themselves been friends or family members of a cancer patient. |

|

Kirk et al.64 2004 |

CA & AU | 72 patients and relatives. | Investigate the preferences and satisfaction levels of cancer patients and their relatives towards disclosure. | Semi-structured audiotaped interviews (average 1 h) with patients and family members, conducted separately after completing a demographic questionnaire. | Six attributes were identified to be important when communicating information: straightforwardness, clarity, empathy, giving time, pacing information and indicating that the patient will not be abandoned. The need for hope was emphasised even by those who have accepted their terminal status. |

|

Hagerty et al.65 2005 |

AU | 126 patients with incurable cancer. | Determine preferences of prognostic discussions among patients with incurable metastatic cancer. | Qualitative data collected through mailed surveys. |

Behaviours identified to increase hope include: offering most up-to-date treatment (90%) appearing to know everything about the cancer (87%), indicating that pain will be controlled (87%). On the other hand, behaviours that decreased hope include: the doctor appearing nervous/uncomfortable (91%), giving the prognosis to the family first (87%), or using euphemisms (82%). Preferences were influenced by a variety of factors including: age, expected survival, information-seeking behaviour and anxiety. |

- AU, Australia; CA, Canada; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; GR, Greece; IT, Italy; JP, Japan; SA, Saudi Arabia; KW, Kuwait.

Discussion

Exploring cancer patients’ expectations from palliative treatments is an intricate and multidimensional issue, because it is closely related to various sensitive issues such as disclosing terminal prognoses, planning end-of-life care, deciding on what information needs to be given and how to best convey it to the patient and their family members. There is also a substantial amount of research addressing these issues from the patients’, caregivers’ as well as the professionals’ point of view. The use of the three primary questions introduced earlier was very helpful in guiding the literature search and the process of organising the findings.

What causes patients’ unrealistic expectations?

One of the main factors contributing to patients holding unrealistic expectations is oncologists’ reluctance to disclose information about the prognosis, especially when it is poor.14, 15 A study that included 258 physicians caring for 326 patients with terminal cancers reported that even when patients requested survival estimates, physicians favoured a frank disclosure only 37% of the time.16 The same study found that physicians knowingly favoured providing overestimated/underestimated estimates to 40.3% of patients, while favouring no disclosure to 22.7%. Most physicians associated this reluctance with fear of causing distress, destroying hope or compromising the patient–doctor relationship.17-19 Some also expressed that respecting the wishes of family members is one of the reasons they withhold information from patients.20 Baile et al.21 collected data from 167 oncologists attending the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 1999, and 40% reported that they occasionally to almost always withhold information when requested by the family. It must be noted, however, that oncologists who were from Western countries were significantly less likely to comply with family requests (P < 0.001). An Australian study reported that requests to withhold information are commonly, but not always, received from family members who are from non-Western cultures.22

Furthermore, it was found that both physicians and patients tend to participate in avoiding prognostic discussions. An ethnographic study observed 35 lung cancer patients throughout their consultations, X-ray appointments, therapy sessions and other treatment activities. The authors identified a quick transition, from discussing the patient's cancer and prognosis, into discussing treatment options and schedules.23 It was finally concluded that both parties “colluded” in refocusing attention on the “treatment calendar” and ignoring the long-term trajectory of the illness, which ultimately led to patients developing false optimism about their recovery.

Other studies have also attributed such inaccurate beliefs to patients not understanding the prognostic information presented by oncologists.24, 25 Australian research indicated that more than half of the patients did not understand terms such as “median survival” and “relative/absolute risk reduction”.26, 27 Patients may also misinterpret ambiguities, and statements such as “this cancer can be treated” or “the cancer is responding to treatment” can be taken to mean that they are going to be cured.23, 28 Higher levels of anxiety or depression, and lower levels of education were linked to an increased likelihood of patients misunderstanding the presented information.29, 30

Independent of factors associated with patients not receiving or understanding the information, some patients continue to hold false expectations even after a clear and realistic prognosis has been provided.31, 32 A pilot study developed a decision-aid tool to help better inform patients with advanced lung cancer about their prognosis and treatment options. Despite the enhanced understanding of potential outcomes and toxicities of therapies, many patients retained unrealistic hopes of their cancer being curable.33 This suggests that although prognostic information may be provided by oncologists, the information might be rejected by some patients as part of a coping mechanism. Denial is a well-studied coping mechanism, which is used to deal with realities perceived to be threatening or unacceptable.34 One study found that while the majority of patients acknowledged their diagnosis and had a realistic expected survival, about 10% chose not to believe in their terminal status and shortened life expectancy.29 After surveying 244 cancer patients to assess both their levels of understanding and denial, Gattellari et al.24 identified denial as a significant predictor of patients holding inaccurate beliefs about their prognosis and goals of treatments.

Why is complete disclosure important?

Over the past few decades, cancer patients have been taking a more active role in the decision-making process, and they are increasingly expecting to be involved in the management of their disease.28, 35 However, the fact that many advanced cancer patients hold inaccurate beliefs about their outcomes, brings up the question of whether enough information is being provided to support their ability to make the right decisions. In fact, it can be argued that without completely understanding their prognosis and the limitations of treatment, such patients may not be considered to have met the true standard of giving an informed consent to their treatment.36

For patients to be able to make choices that are consistent with their needs, they have to be well informed about the expected benefits and risks of each treatment option. Patients with advanced cancer are willing to accept intense chemotherapy regimes even if they believe there is only a 1% chance of cure.37 Weeks et al.9 found that patients who expected a 6-month survival were 2.6 times more likely to pursue aggressive anticancer therapies instead of palliative treatments. These patients had the same survival as others who received palliative care, but were more likely to be readmitted to hospitals, undergo attempted resuscitation or die during ventilator support. This indicates that patients who lack knowledge about the possibility of being cured may be compromised in their ability to make treatment decisions that reflect their actual needs.

Moreover, beliefs that disclosing prognostic information may result in increased anxiety and depression or destroy hope have not been supported by research findings.38 Studies have found that increasing patients’ awareness using audiotaped consultations,39 or pre- and post-consultation questionnaires was not associated with increasing levels of anxiety, sadness or compromising the patient–doctor relationship.40, 41 Patients who reported having life expectancy, or end-of-life discussions with their physicians did not have higher depression levels; they also had lower rates of ventilation, resuscitation and earlier enrollment into hospice care.42 Patients who did not know their terminal prognosis actually had greater levels of anxiety and depression.29 Hope was maintained even after honest discussions that informed patients about having a poor prognosis, low likelihood of response to treatment or no chance of cure at all.43 Similarly, hope increased or at least was preserved in parents of children with cancer after realistic information was given, even when prognosis was poor.44

Disclosing a terminal prognosis allows patients to better cope with their illness, and shortens the necessary adjustment process. When information is given in a supportive and sensitive manner, it can create an atmosphere of openness and trust, in which patients are empowered to clarify priorities, reset goals, and focus their hopes on achievable possibilities such as a comfortable and meaningful end-of-life period.42, 44, 45 Prognostic discussions have also been associated with facilitating family members’ preparations for possible death,46 and increasing caregivers’ satisfaction with end-of-life care.47

Finally, surveys of patients and family members have demonstrated a great desire for detailed prognostic information. For example, in a national U.K study that included 2331 cancer patients, 87% wanted as much information as possible regardless of type or stage of cancer.48 Similarly, in an Australian study the majority of patients wanted information about side effects and treatment goals (95%), longest survival with treatment (85%) and how long they have to live (59%).49 In another study, 55% of palliative care patients and 75% and their caregivers who were interviewed retrospectively, reported that they would like to have discussed life expectancy with their physician.50

How to approach discussing prognostic information?

While patients and caregivers are increasingly favouring full disclosure and more involvement in the decision-making process, physicians continue to face challenges when disclosing terminal prognoses. These challenges include considering their obligation to patient's autonomy, while deciding how much information needs to be given, and how much the patient wants to know.17 Additionally, physicians sometimes find it difficult to convey such information in a manner that is realistic, but also preserves the patient's hope.18, 51 It is even more challenging when attempting to meet the needs of family members,21 and patients from different cultural backgrounds with varying views on disclosure.52, 53 To investigate the optimal ways of approaching prognostic discussions, a review of current literature was performed to explore preferences of patients and caregivers regarding when and how they prefer such information to be provided.

In an Australian study involving 126 patients recently diagnosed with an incurable cancer, 59% wanted to know about expected survival when first diagnosed; 34 and 40% wanted to be asked about when they prefer discussing expected survival and dying, respectively.49 Also, 45% of these patients wanted the specialists to be the one initiating such discussions. Only 11% said they never wanted to discuss dying/palliative care and 10% were unsure. Older patients and those with higher anxiety scores were significantly less likely to request prognostic information, and having a poorer prognosis was also predictive of patients wanting less information.54 The majority of patients from English-speaking backgrounds prefer a detailed prognosis,54-56 where as those from other backgrounds such as Greek,52, 57 Italian,58, 59 Japanese,60 Chinese,61, and Middle Eastern62, 63 seem to vary, with a tendency to prefer non-disclosure.

Several aspects have been identified to affect patients’ satisfaction with the communication style of conveying prognostic information. For example, the level of honesty and straightforwardness, simplifying the information and using more than one way to present the message.64 Believing that the provision of information was not honest, direct or detailed enough may lead to more frustration and uncertainty as patients perceive that the doctor is withholding even more frightening information.39 Pacing the information, expressing empathy, compassion and allowing patients to ask questions or address concerns also enhance the communication process.

Finally, one of the most important aspects of disclosing a poor prognosis is the provision of hope, with patients expressing a continuing need for hope even after they have accepted their terminal status.64 Behaviours known to increase hope include being offered most up-to-date treatment, oncologist appearing to know everything about the cancer, being told all treatment options and that pain will be controlled, occasional use of humour and an indication that health professionals are not giving up, and that the patient will not be abandoned.64, 65 Contrarily, behaviours that decrease hope include doctor appearing nervous/uncomfortable, giving prognosis to the family first, avoiding prognostic information, or only talking about treatments.65 Overall, younger patients and those who are more anxious, expressed a greater need for emotional support for themselves and their families, while patients who had been diagnosed with a metastatic disease for longer times and those with longer life expectancy were more likely to favour realism.65

Conclusion

Patients with advanced cancer commonly have misunderstandings about their illness, overestimate their prognosis and hold unrealistic expectations from their palliative treatments. This is not surprising when considering all the challenges associated with discussing sensitive issues such as a terminal prognosis, lack of cure and end-of-life care. However, without fully understanding their prognosis and the limitations of treatment, patients may be compromised in their ability to make choices that are consistent with their needs. As a result of this lack of understanding, patients may choose to undergo futile long-course therapies at the expense of quality of life.

Communication styles play a major role in patients’ experience; sensitive and supportive communication of information that encourages patients in decision-making has shown to provide hope by helping patients develop coping strategies and focus their goals on achieving a comfortable and meaningful end-of-life period. It must be remembered, however, that patients have very different views on disclosure, and these views are influenced by many factors including cultural backgrounds, belief systems, coping strategies and extent of the disease. Therefore, it is recommended that oncologists adopt a more patient-oriented approach and consider individuals’ needs when discussing prognostic information. Also, considering the high level of information needs reported by patients, it is recommended that more research is conducted in order to define the relation between prognostic awareness and patients’ satisfaction, identify communication barriers faced by patients and the interventions that could be used to overcome such barriers. It would also be interesting to investigate how patients’ high expectations from palliative therapies would affect their compliance to finish the intended course of treatment, especially because conclusive data on this topic are still lacking.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges Yobelli Jimenez for her guidance, support and reviewing the manuscript before submission.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.