Understanding the variation in offender behaviour and risk factors in cases of homicide perpetrated against the UK homeless population between the years 2000 and 2022

Abstract

The homeless population remains understudied, and their victimisation is unreported, especially homeless victims of homicide. With the number of people faced with homelessness increasing, the heightened rates of victimisation for violent crimes throughout this population becomes even more concerning. A review of the literature revealed an absence of meaningful research beyond basic descriptive statistics of rates of homeless homicide in the UK. The current study explores the behavioural variation and risk factors associated with the victims and perpetrators of 19 cases of homeless homicide in the UK. A content analysis was first conducted to derive 22 case variables. Smallest Space Analysis was then employed to analyse the cases according to the variables selected. The themes produced in the SSA output were comparable to that of Canter's Victim Role Model: Victim as Object, Victim as Person and Victim as Vehicle. The current study lays a foundation for developing an understanding of the variation in behaviour across cases of homeless homicide and may serve to inform preventative measures.

1 INTRODUCTION

According to the most recent official statistics, it is estimated that approximately 2688 people are sleeping on the streets on any given night in the UK (Office for National Statistics; ONS, 2021a). An estimated sum of 278,110 homeless individuals were sleeping on the streets, in hostels, or in temporary emergency accommodation provided by the council and social services in March 2022 (Crisis, 2022; Department for Levelling up Housing and Communities, 2022; Shelter, 2021). While these figures demonstrate a 1.4% decrease since 2020, homelessness has increased by 165% since 2010 (Ministry of Housing, 2022). In addition, the number of individuals threatened with homelessness has increased by 7.3% in the last year (ONS, 2021a). Thus, despite a short-term decrease in the number of individuals classed as homeless at the time of the most recent statistics, homelessness and the risk of becoming homeless is on the rise, forcing many more people into vulnerable circumstances.

This risk of homelessness is influenced by many factors including a lack of social housing, the pressure of private rent payments, and unexpected life events (Shelter, 2017). One such factor prominent at the time of writing is the significant increase in the cost of living in the UK. With the cost of food, fuel, household bills and rent soaring, some are going without basic necessities in an attempt to keep a roof over their heads (Fitzpatrick et al., 2021). This is illustrated in the rapid increase in families accessing support from food banks and soup kitchens in the last 7 months (Emmaus, 2022). From the increased cost of living alone, councils have estimated that homelessness in the UK could increase by a third by 2024 (Booth, 2022) rapidly increasing the number of people in vulnerable circumstances.

1.1 Vulnerability of homeless

Homeless individuals are known to be one of the most vulnerable groups in society, a marginalised population often demonised by assumptions of criminality and addictions (Donley & Gualtieri, 2017; Reynalds, 2006; Truong, 2012). Such stigmatic views are strengthened by negative portrayals of the homeless in the media, reinforcing an “us” versus “them” mentality and frequently blaming them for their current circumstances, citing laziness as the main cause of homelessness (Buck et al., 2004; Cloke et al., 2001; Lind & Danowski, 1999).

1.2 Violence towards homeless

It is not uncommon for homeless individuals to have experienced traumatic events or historic abuse, before becoming homeless (National Homelessness Advice Service, 2021). The instability in their circumstances coupled with a lack of protection from mental and physical stressors can often produce or exacerbate physical and mental health issues, causing a heightened prevalence of illness in comparison to that observed in the general population (Fransham & Dorling, 2018; Homeless Link, 2022). Homeless individuals must then navigate risk-filled and unpredictable environments in which the threat of repeated victimisation is increased (Lee & Schreck, 2005) and continues to increase if individuals remain longer in these circumstances (Garland et al., 2010) with the homeless being 13 times more likely than the general public to fall victim of a violent crime or 47 times more likely to be a victim of theft (Crisis, 2016). A higher percentage of homeless individuals have been found to engage in other risk-taking behaviours such as sex work and substance use, amplifying their susceptibility to criminal victimisation further (Larney et al., 2009; Salfati et al., 2008; Wenzel et al., 2001). This sharply elevated risk is reflected in victim statistics, in which homeless individuals are 17 times more likely to have been the target of violent crime than those with permanent homes (Foster, 2016; Nilsson et al., 2020). In a survey conducted with 458 rough sleepers in England and Wales, respondents reported having been threatened with violence (48%), deliberately hit or kicked (35%), had items thrown at them (34%), urinated on (9%) and sexually assaulted (7%) (Crisis, 2016). These violent attacks on homeless individuals have more than doubled since 2014 (Greenfield & Marsh, 2018). Unfortunately, these victimisation rates are likely far higher, as an estimated 53% of violent crime committed against the homeless goes unreported to the police (Walker, 2018) due to mistrust in the police, a lack of witnesses or evidence, feelings of unworthiness or an unwillingness to break cultural constraints against ‘grassing’ (Wardhaugh, 2000).

Violent attacks against homeless individuals are disproportionately more likely to result in homicide compared to those perpetrated against individuals with permanent accommodation (Stateman, 2008). While it is known that homicide as a cause of death is grossly overrepresented throughout the homeless population (Dietz & Wright, 2008), the exact incidence rate is unknown. It is possible that the deaths of homeless individuals may remain unknown due to severed relationships with family members or a lack of social connections close enough to warrant concern being raised to the authorities (Mabhala et al., 2017). This lack of clarity in official statistics surrounding the homeless population could also be attributed to the difficulty in establishing a cause of death in cases when it may not be obvious, that is, when fatal injuries are not immediately apparent. In a population exposed to a rapidly elevated incidence of illness and addiction, post-mortem analysis may not always prove to be useful (Aldridge et al., 2019). For example, recent statistics on homeless mortality rates lists ‘accidental death’, that is, drug overdoses, suicide and ‘undetermined’ as the most common causes of death (ONS, 2021b). This proportion of unexplained cases coupled with an 80% increase (from 714 in 2019 to 1286 in 2021) in recorded annual homeless deaths since 2019 (Museum of Homelessness, 2021) is concerning and could potentially suggest an increase in the number of homeless homicides.

1.3 Homelessness research

A thorough review of the literature revealed an absence of published research surrounding homeless victims of homicide in the UK. Instead, research solely focused on homeless perpetrators of crime or homeless victims of non-fatal violent attacks (Centrepoint, 2019; Crisis, 2016; Sefton Supported Housing Group, 2019; Unified, 2022). The lack of research could be attributed to the perceived relative infrequency of homeless homicide (Hipple et al., 2016), although as stated previously, such cases may be underrepresented in official statistics. Others have referenced the scarcity of official statistics and the limited availability of detailed reports in explaining the gap in homelessness research (Cloke et al., 1999; Scurfield et al., 2009), but such claims have been contradicted by studies conducted in other countries demonstrating the utility of cross-referenced open-source data in exploring crimes committed against homeless individuals (Gruenewald, 2013).

Research conducted around the world has demonstrated that ‘unnatural’ deaths of homeless individuals are more common than that of the general population, with homeless individuals over 9 times more likely to complete suicide (Crisis, 2011) and twice as likely to be a victim of homicide than housed individuals (Baggett et al., 2013; Gruenewald, 2013; McDaniel, 2022; Roncarati et al., 2018; Slockers et al., 2018; Stanley et al., 2016). Although this information is useful in illustrating the heightened occurrence of homicide perpetrated towards members of the homeless population in other countries, such research may be considered limited in its usefulness in contributing to policy and police practice. Further case detail is required to enhance the protection of homeless individuals and assist in preventing such crimes from occurring.

1.4 Research using multidimensional scaling analysis

In the past, studies using multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis have provided this additional depth in exploring criminal variation. The introduction of MDS techniques follows the notion that the combination of potential behaviours carried out during an offence is infinite and to categorise an offender into strict ‘types’ created from a predetermined list of expected behaviours would be a gross oversimplification (Canter & Youngs, 2009). It has instead been suggested that variation in criminal behaviour would be more accurately represented on a circular spectrum in which offenders may appear to primarily belong to one group but may also share certain characteristics with several offence ‘themes’ (Canter, 2000). MDS often involves prior content analysis to identify the variables associated with each case before inputting them into the analysis software as data points. MDS software calculates a measure of co-occurrence between each variable and represents them as points in a spatial image. It is the distances between each variable within the geometric space that indicate the strength of their co-occurrence, making interpretation easier than that of the absolute values (Ioannou & Debowska, 2014). The clustering of variables determined by the strength of their associations enables researchers to develop models of offence themes using the MDS output.

Investigative psychologists have previously employed MDS techniques to enhance understanding of offender variation in the perpetration of a wide variety of phenomena. Examples of such models include those exploring suicide by the examination of suicide notes (Synnott et al., 2018), acts of terrorism (Horgan et al., 2018), filicide (McKee & Egan, 2013) and school shootings (Ioannou, Hammond, & Simpson, 2015). Numerous studies have employed MDS techniques utilising variables relating to victim, perpetrator and offence in their exploration of homicide (Salfati, 2000, 2003; Salfati & Bateman, 2005; Salfati & Canter, 1999; Salfati & Dupont, 2006; Salfati & Park, 2007). Examples of specific variables analysed throughout previous research include nature of victim–perpetrator relationship (Greenall & Wright, 2020; Salfati & Canter, 1999), criminal history and background of perpetrators (Trojan & Salfati, 2011, 2016), crime scene behaviour (Salfati & Dupont, 2006; Salfati & Park, 2007; Santilla et al., 2001) and method of homicide (Hakkanen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Salfati, 2003). MDS analysis has been successfully applied across the world to populations in Korea (Sea & Beauregard, 2021), Belgium (Thijssen & Ruiter, 2010), Finland (Santilla et al., 2001), Greece (Salfati & Haratsis, 2001) and Spain (Pecino-Latorre et al., 2019) in differentiating homicide cases and identifying offence themes. One model evident throughout MDS homicide research has categorised cases on the basis of motivation, enabling the broad classification of homicide cases as either instrumental in that the crime is perpetrated in the pursuit of personal gain or expressive in nature and driven by emotion (Fox & Allen, 2014; Salfati, 2000, 2003; Salfati & Bateman, 2005; Thijssen & Ruiter, 2010). Others have sought to examine the ways in which the victim is perceived by the perpetrator and the roles assigned to them in the execution of the offence.

One such model derived from MDS techniques is Canter's (1994) Victim Role Model, which proposed three victim narratives differentiated by the style of interpersonal relations between victim and offender: Victim as Object, Victim as Person and Victim as Vehicle. When the victim is assigned as the Object narrative, the offender treats them as something to be used and controlled to provide some benefit to themselves, whether that be a financial gain or psychological satisfaction from asserting control. The victim's response is unlikely to influence the offender's actions to any degree (Canter, 2000) with the offender typically failing to acknowledge the victim as a human being (Canter & Youngs, 2012). Contrastingly, the Victim as Person narrative demonstrates an awareness of the victim as an individual but remains a person to be taken advantage of (Canter, 1994). In cases following this narrative, interactions are more likely to be two-way with the victim's reaction having the potential to influence the offender's actions (Canter, 2000). Perpetrators show interest in the victim as a person, making attempts to form some sort of relationship and often stealing personal belongings from the victim following the crime. In the third narrative, Victim as Vehicle, the perpetrator uses the victim as a vehicle for expressing their own emotions and/or desires. Victims in this narrative are typically subject to extreme violence and abuse driven by perpetrators' intense emotions (Canter & Youngs, 2012).

This model has been repeatedly tested and applied across a multitude of crime types including serial homicide (Hodge, 2000), sexually motivated homicide (Bennell et al., 2013), and human trafficking (Ioannou & Oostinga, 2015).

By exploring the behavioural components of offences and the potential risk factors identified in the perpetrator's past, findings may serve to highlight individuals who may be more predisposed to commit certain crimes (Kocsis & Palermo, 2015), inform investigations by identifying crimes which may be linked (Salfati & Bateman, 2005) or aid suspect identification (Santilla et al., 2003). Alternatively, MDS research can be used to draw attention to those who may be at an increased risk of victimisation (Fritzon & Ridgway, 2001) and effectively contribute to the development of prevention and intervention strategies.

2 THE CURRENT STUDY

The current study aimed to explore the variation in behaviour in cases of homicide perpetrated against homeless individuals in the UK. This research builds on the limited literature available, through a closer examination of case details beyond merely their occurrence rates. This was achieved through the exploration of the behavioural components of the crime, and the risk factors associated with the perpetrators and victims of each case.

3 METHODOLOGY

The current study utilised pre-existing data published in the public domain relating to homeless victims of homicide in the UK and has received full ethical approval by a UK-based higher education institution. Search terms used for data collection included “homeless”, “homicide”, “murder” and “victim”. The data was primarily sourced from articles published by reputable news outlets such as the BBC, The Guardian, The Independent and local newspapers. Information from other journalistic websites was also included. All information was cross-referenced with at least two other sources prior to its inclusion within the data set to retain a high level of accuracy and detail. Names of victims have been replaced with letters to protect their identities.

While the Internet search uncovered a total of 28 cases of violent assaults perpetrated against homeless individuals in the UK, cases were excluded if the attack did not result in the death of the victim, or if insufficient information was available.

The final sample consisted of 19 homicides, perpetrated by a total of 39 offenders between the years 2001 and 2021 in the UK. The age of the victims spanned from 21 to 69 years of age. The mean age of the victim was 45.47 (SD = 13.83), while the perpetrator's mean age was 30.15 (SD = 12.66). The age of perpetrators ranged from 14 to 60 years old. Out of the 19 cases, the sample of perpetrators consisted of 36 males and 3 females. There were 16 male victims and 3 female victims.

Content analysis was conducted to examine each case and identify the seminal variables associated with each. To aid in the selection of such variables, similar research conducted into other types of homicide was consulted (Canter & Fritzon, 2011; Ioannou, Hammond, & Simpson, 2015; Ioannou & Oostinga, 2015). Such research has included variables reflecting the perpetrators' previous offence history (Salfati, 2003), premeditation (Larkin & Canaparo, 2020), the use of weapons (Kamaluddin et al., 2017), the use of ‘overkill’ (Solarino et al., 2019) and the nature of the relationship between perpetrator and victim (Santila et al., 2003). The selection of variables was also informed by additional criminological research regarding risk factors preceding the perpetration of an offence including any history of mental health issues (Matejkowski et al., 2008), intoxication of the victim or perpetrator and/or substance abuse issues (Gerard et al., 2015).

A total of 22 variables were identified throughout the cases and were coded dichotomously in terms of their presence or absence. Behavioural variables were only selected if clearly observable at the crime scene. All behaviours with the potential for misinterpretation were not included. Inter-rater reliability was carried out during data gathering and analysis. A full description of all variables used is provided in Appendix 1.

3.1 Multidimensional scaling analysis

The study utilised pre-existing data regarding 19 homeless victims of homicide gathered from online sources. Content analysis was performed on the data to identify variables relevant to the perpetrators, victims and the circumstances surrounding each case. A form of non-metric MDS analysis software (Hudap) was then used to input the variables and analyse the co-occurrence of each throughout the cases, generating themes to compose the model of offending. The current study was conducted to increase awareness of the risk of homicide victimisation for homeless victims, as well as to provide insight into the variation of offender behaviour when targeting this population. In turn, this may serve to inform preventative measures by highlighting those who may be more at risk. While the findings may also be used to potentially indicate individuals who may be predisposed to target the homeless, it is acknowledged that this cannot be taken as absolute, and caution must be employed to prevent harmful labelling.

Regional hypotheses were proposed regarding the positioning of the variables throughout the MDS plot. The experimental hypothesis is based on the premise that variables with similar underlying themes will be more likely to be positioned closer together, indicating a co-occurrence between variables within the thematic structures formed. This regional hypothesis has proven appropriate throughout other studies utilising MDS techniques to investigate behaviour, personality and emotion (see Plutchik & Conte, 1997). Alternatively, the null hypothesis stated that the variables under investigation have no clear relationship to one another, and thus the dispersion of variables in the MDS plot will demonstrate no discernible pattern. Hypotheses were therefore tested by the visual examination of the MDS configuration.

4 ANALYTIC APPROACH

The current study used Smallest Space Analysis (SSA; Lingoes, 1965), a form of non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) in its exploration of the sample cases. Initially, the variables were inputted into SPSS at a nominal level and were coded as either 0.00 (absent) or 1.00 (present). Once each case had been coded, the data was transferred to HUDAP to run the SSA. SSA has been employed extensively in comparable studies of different crime types (DeBlasio et al., 2022; Ioannou et al., 2015, 2018, 2018; Ioannou, Synnott, Lowe, & Tzani-Pepelasi, 2018; Synnott et al., 2018).

In the plots generated by the software, variables are visually represented as points in a notional ‘space’. The positioning of each variable is systemically determined by the relationships between all other variables in the data set, with their proximity demonstrating the strength of correlation. Put simply, should two variables share a stronger correlation, the points representing these variables will be positioned closer together in space. In contrast, variables with weaker correlations will be further apart. This representation of co-occurrences as ranks of proximities makes the interpretation simpler in comparison to representation as absolute values. The plots produced by SSA also include a radial facet in which the distance from the centre of the radex is an indicator of variable frequency, with variables close to the centre occurring more frequently across the sample cases.

The plots produced by SSA enable the identification of any underlying relationships existent throughout the data (Jaworska & Chupetlovska-Anastasova, 2009) demonstrated by the clustering of points. Where appropriate, regional lines may be drawn throughout the clusters of variables based on similar conceptual content. These regions of contiguity form the ‘themes’ observable throughout the data set. The positioning of regional lines was agreed upon between researchers.

SSA produces several values of importance that can be utilised alongside the visual outputs. The coefficient of alienation (Borg & Lingoes, 1987) is an indication of the spatial representation's goodness of fit. This signifies how accurately the distances between points in the geometric space represent the co-occurrences observed between each variable, with a smaller coefficient of alienation implying a better fit. Academics have suggested that an acceptable score will range between 0.15 and 0.24 (Donald, 1995); although others have claimed that this is overly simplistic as determining how ‘good’ or ‘bad’ the fit is, it is dependent on a number of variables including the strength of the interpretation framework and the existence of error in the data (Borg & Lingoes, 1987). The co-occurrences themselves are measured using Jaccard's coefficient which, calculates the proportion of co-occurrences between any two variables as a proportion of all occurrences of both variables. Jaccard's is the preferred option for dichotomous data as it measures the association of the variables while ignoring joint non-occurring variables. It is appropriate for use with this type of data, as it is not influenced by the absence of variables. If a variable is not present it does not necessarily mean that it did not occur; it might just not have been reported. SSA is suitable not only for hypothesis testing but also for hypothesis generating. As such, it was an optimal technique for the current exploratory analysis.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Case characteristics (or risk factors) in the present study

See Table 1 for information regarding the frequency of variables present across the sample of homeless homicide cases.

| Case characteristics (or risk factors) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Victim rough sleeping | 18 | 94.74 |

| Victim under the influence (UTI) | 17 | 89.47 |

| Victim substance addictions | 17 | 89.47 |

| Bodily weapon | 14 | 73.68 |

| Premediated | 14 | 73.68 |

| Multiple perpetrator (2+) | 13 | 68.42 |

| Public place | 12 | 63.16 |

| Perpetrator—Victim strangers | 11 | 57.89 |

| Perpetrator previous violent offences | 9 | 47.37 |

| Perpetrator under the influence | 9 | 47.37 |

| Blunt force weapon | 9 | 47.37 |

| Perpetrator substance addictions | 8 | 42.11 |

| Overkill | 7 | 36.84 |

| Steals | 7 | 36.84 |

| Perpetrator homeless | 6 | 31.58 |

| Perpetrator diagnosed mental health | 6 | 31.58 |

| Bladed weapon | 4 | 21.05 |

| Body hidden | 4 | 21.05 |

| Deception | 3 | 15.79 |

| Fire as a weapon | 2 | 10.53 |

| Drowned | 1 | 5.26 |

| Dismemberment | 1 | 5.26 |

5.2 SSA of case characteristics (or risk factors)

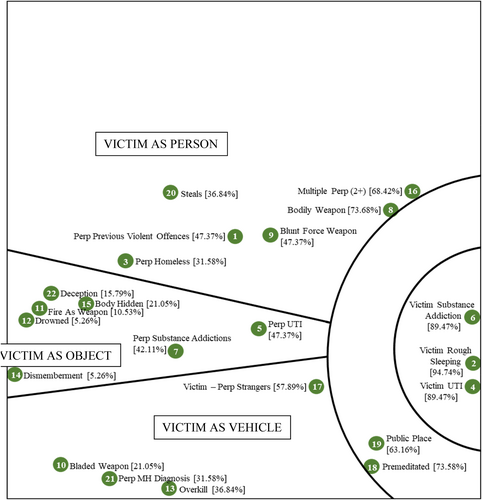

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 22 case characteristics (or risk factors) for the 19 cases of homeless homicide on the two-dimensional SSA. The coefficient of alienation of 0.17 indicates an appropriate fit of the spatial plot in comparison to the co-occurrences of the case characteristics. The regional hypothesis states that items that have a similar underlying theme will be found in the same region of the SSA plot. To test the hypothesised framework of homeless homicide case characteristics, the SSA spatial representation was examined to establish whether different themes of cases could be established.

Two-dimensional Smallest Space Analysis (SSA) plot of behaviours (and risk factors) present throughout cases of homeless homicide with regional interpretation. Coefficient of Alienation = 0.17.

As shown in Figure 1, the centre of the radex encompasses three variables present across the majority of the sample cases: victim rough sleeping (2), victim substance addition (6), and victim under the influence at the time the crime was committed (4). The outer rim of the inner radex shows that a degree of premeditation (18) was frequently evident, and the attacks commonly occurred in a public place (19). Cases were considered to involve an element of premeditation when the offender evidently set out to target a victim known to them, or when they had been carrying/sourced a weapon shortly before the attack took place. In cases where the victim and perpetrator were strangers, it may be that the victim was perceived by the perpetrator as representing something the offender held negative thoughts/beliefs towards and thus became a target to project these emotions. A visual examination of the SSA plot confirmed that beyond the inner radex, the plot can be divided into three distinct areas or themes comparable to Canter's (1994) Victim Narrative Model: Victim as a Person, Victim as an Object and Victim as a Vehicle.

Victim as Person: In the top region of the plot (Figure 1), six variables form the second theme: the perpetrator themselves was homeless (3), the perpetrator had previously been charged with violent offences (1), the offence was carried out by multiple perpetrators (16) using either a blunt force weapon (9), or bodily weapon (8), and following the attack, the perpetrators stole from the victim (20). Generally, this theme was made up of offenders who were also homeless at the time of the offence, and who attacked other individuals whom they were sleeping with on the streets or in homeless camps. Typically, the perpetrator had attacked the victim using bodily weapons or blunt force weapons, which they had in their possession to increase feelings of security while sleeping on the street. The perpetrator acknowledges the victim as a person but for reasons they become a person to be gained from in some way. With many homeless people bedding down with others to increase feelings of security, this may explain the higher instance of cases in this theme involving multiple perpetrators.

A case illustrating this theme is the death of ‘A’ at the hands of two males who were 25 years of age. ‘A’ and the two perpetrators had been sleeping rough together in Manchester City Centre. Following a disagreement, the two perpetrators beat ‘A’ to death with a baseball bat, hammer and broomstick. The perpetrators then stole belongings from ‘A's tent.

Victim as Object: The theme highlighted by the central segment outside of the inner radex (Figure 1) comprised six variables: the perpetrator was under the influence at the time of the attack (5) and also suffered from substance addictions (7). The perpetrators in this theme may have used deceptive tactics (22), killed the victim by drowning them (12) or used fire as a weapon (11). There were also instances during which offenders in this theme dismembered the victim (14) before hiding the body (15). Typically, perpetrators in this theme suffered from substance addictions and were under the influence at the time of the offence, which may have altered their perception of interactions or disinhibited their behaviour, potentially increasing the likelihood of aggression and violence. Despite being intoxicated, offenders belonging to this theme appear to be more calculated in comparison to that in the other two themes, using deception to manipulate the victim and making some effort to conceal the body.

A case example illustrating this theme is the death of ‘B’. The 54-year-old male perpetrator was under the influence at the time of the attack. He had purchased a 4-L jerry can and petrol before walking 40 minutes towards the hut where ‘B’ was sleeping. He covered the hut in petrol before setting it alight. A second case example relative to this theme is that of ‘C’ who was invited into the perpetrator's home following offers of providing somewhere for him to stay. Evidence suggested the perpetrator was an alcoholic and had been drinking heavily and continuously for 2 days with little sleep. ‘C’ was tortured for many hours before his body was dumped in a sleeping bag not far from the perpetrator's residence.

Victim as Vehicle: In the bottom region of the plot (Figure 1), five variables form the third theme: the victim and perpetrator were strangers (17), the perpetrator had previously been diagnosed with a mental health disorder (21), some element of overkill was evident in the case (13) and the perpetrator used a bladed article as a weapon (10).

These variables appear to be indicative of a mentally unwell individual, using violence and homicide as a means of benefitting themselves. Such benefits to the perpetrator may include a cathartic release in that the offence is used as a way of expressing pent-up emotion or establishing feelings of power and control. The existence of extreme violence in this theme, such as overkill and dismemberment, supports the notion of perpetrators using the offence as a means of venting rage. Such rage may be purposefully directed towards the victim due to the perpetrator's perception of what the homeless population represent. Alternatively, the perpetrators may have simply selected a homeless victim due to their exposed, vulnerable state making them an ‘easier’ target at which to direct their aggression. In this instance, the perpetrator(s) fail to recognise the victim as a human being and instead react towards the victim as though they were an object. A lack of effort in concealing the body may suggest an absence of planning or rational thought on behalf of the perpetrator, with the impulse of violence consuming their thoughts and driving their actions.

A case illustrating the heightened violence within this theme is the death of ‘D’ who was killed whilst sleeping rough inside of a bus station. The victim was stabbed many times in their upper body and neck. The perpetrator was known by support services in the area due to having suffered long-term mental health issues.

Please see discussion section for further detailed explanation of themes and exploration of the surrounding literature.

5.3 Testing the framework—Distribution of cases across themes

While the SSA indicated that the case characteristic can be organised into three psychologically meaningful themes, the offenders/cases themselves are not classified accordingly. For the model to have value, it is important to investigate whether it is possible to classify the perpetrator(s) of each case as belonging to one of the three themes identified. Consequently, each of the 19 cases was analysed to assess whether it could belong to one of the themes according to the variables present in each case. A case was considered as predominantly belonging to a particular theme if the number of variables present from that theme was more than the sum of those from the other two themes. Cases were non-classifiable if an equal number of variables from two or more themes were present. This classification method has been employed throughout previous research by Canter and Fritzon (2011), Salfati and Canter (1999), Youngs and Ioannou (2013) and Ioannou and Oostinga (2015).

Following this system of classification (see Table 2), a total of 89.47% of cases (17 out of 19) could be classified as predominantly belonging to the Victim as Person, Victim as Object, or Victim at Vehicle theme. More specifically, eight cases (42.11%) corroborated with the Victim as Object narrative, six cases (31.58%) with the Victim as Person narrative and three cases (15.79%) as Victim as Vehicle. Two cases (10.53%) were considered as non-classifiable. These results would suggest that the distinct themes identified within the SSA plot are a reasonably good representation of the variation in criminal behaviour observed throughout cases of homeless homicide.

| Theme | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Victim as object | 8 (42.11%) |

| Victim as person | 6 (31.58%) |

| Victim as vehicle | 3 (15.79%) |

| Non-classifiable | 2 (10.53%) |

6 DISCUSSION

The current study explored the potential for developing a model for differentiating cases of homeless homicide based on the case characteristics. The three themes identified corroborated with Canter's (1994) Victim Role Model, centred around the interpersonal transaction with the victim: Victim as Person, Victim as Object, and Victim as Vehicle. The regional hypothesis stating that variables with similar underlying themes would be grouped closely together in the regional space was therefore accepted.

6.1 Victim as Object

The most dominant theme in which nearly half (42.11%) of the cases were classified was the Victim as Object narrative. In this theme, the perpetrators were likely to have substance addictions and were under the influence of substances at the time of the attack. Offenders typically used techniques such as drowning, using fire as a weapon and dismemberment in the perpetration of the crime. Before the attack, perpetrators may have deceived their victims to some degree, to incite trust or to get the victim to a more hidden location. Some effort was made to conceal their body.

Offences in this theme appear to occur out of the perpetrator's disregard for the victim as a person. This could be likened to the Victim as Object classification in Canter's (1994) Victim Role Framework. The Victim as an Object theme is centred on dehumanising and depersonalising the victims (Canter & Heritage, 1990), seeing them as having very little, if any, human significance or emotion. The victim simply becomes an object for the offender to act upon (Canter & Youngs, 2009), showing a complete lack of empathy towards the victim (Canter & Youngs, 2012). The dismemberment of the victim's body may serve to illustrate the offender's disregard for the victim as a person, instead becoming an object to manipulate (Chopin & Beauregard, 2021). It could be argued that this perception of homeless people as objects is reinforced throughout the media, strengthening the stigma surrounding the homeless as illegitimate members of the community (Belcher & DeForge, 2012; Donley & Gualtieri, 2017). A review of five British newspapers highlighted a persistently negative representation of homeless individuals, typically implying links with criminality and portraying them as “undeserving” (Cloke et al., 2001; Forte, 2002; Min, 1999). Such representations are dangerous in perpetuating negative opinions towards the homeless, and potentially implying that violence towards the homeless is somehow warranted or less despicable than that perpetrated against other members of the community (Borchard, 2005; Weber et al., 2020; Ziegele et al., 2018). This is illustrated throughout several cases in which a homeless individual was murdered for a “dare” or because it was considered to be “funny” by the perpetrators. The disinhibiting effect of drugs and alcohol may further contribute to the likelihood of violence (Duke et al., 2018; Lindsay, 2012; Morgan & McAtamney, 2009).

6.2 Victim as Person

The second theme, evident in 31.58% of cases was the Victim as Person narrative. Perpetrators in this theme were typically homeless themselves and had received previous convictions for violent offences in the past. Offences in this theme were perpetrated by two or more individuals who used bodily weapons or blunt force weapons already on their persons in the perpetration of the offence. Perpetrators then stole items from the victim following the offence. In this theme, the victim is acknowledged by the perpetrator as a person but is undervalued as an individual and becomes a target to be taken advantage of (Canter & Youngs, 2012). Many of the victims in this theme were known to the perpetrators prior to the offence, through homeless accommodation or from sleeping rough with one another on the streets. This could have contributed to the perpetrators' acknowledgement of their victims as individuals but did not serve as a protective factor. Theft of the victim's belongings following the offence implies an interest in the victim as a person rather than simply their body (Hodge, 2000).

This style of offending can emerge out of a distorted approach to human interaction in which the perpetrator's interpersonal relations become frequently coercive and/or abusive in nature (Youngs & Ioannou, 2013). A history of prolonged abuse or repeat victimisation is not uncommon for individuals experiencing homelessness (Green et al., 2012; Osuji & Hirst, 2015; Shelter, 2022). It is possible that exposure to abusive behaviour such as this may taint future interpersonal relations by distorting individuals' perception of appropriate interactions with others (Davis & Petretic-Jackson, 2000; Wojcik et al., 2019).

Additionally, the lack of circumstantial control that often comes with being homeless can cause individuals faced with homelessness to experience feelings of bewilderment upon release from prison should support fail to be implemented, leading to an increased reconviction rate within the homeless population (Covin, 2012; Kertesz et al., 2003; Kushel et al., 2005; Metzger & Cuppari, 2020). Perpetrators within this theme had received convictions for violent offences in the past, with the homicide potentially demonstrating an upward trajectory in the extremity of their offences perhaps in pursuit of a longer prison sentence. Prison can offer the shelter, protection and structure frequently absent in the lives of homeless individuals, with many expressing a preference for being in prison as opposed to living on the streets (Couloute, 2018; Latessa, 2004; Williams & Stickley, 2010). For this reason, perpetrators within this theme may lack the inhibitions, which would typically prevent them from committing illegal acts, as prison is no longer seen as a deterrent but instead becomes a lifeline (McVerry, 2008; Schneider & Jones, 2021).

6.3 Victim as Vehicle

The third and final theme, Victim as Vehicle, encapsulated 15.79% of cases. Offenders in this theme had received previous mental health diagnoses and, using a bladed weapon, demonstrated more extreme violence towards their victim (overkill). Victims were not known to the offender prior to the offence. Extreme violence coupled with the fact that the victim and perpetrator were strangers in this theme may be considered unusual amongst the existing homicide literature, given that overkill is often perceived as primarily expressive in nature (Greenall & Wright, 2020; Martins, 2019; Salfati & Haratsis, 2001) and more frequently present throughout intrafamilial or intimate-partner homicides (Block et al., 2001; Kopacz et al., 2023; Last & Fritzon, 2005; Trojan & Krull, 2012). However, overkill is still present in a smaller proportion of stranger homicides, particularly when the perpetrator has been known to have exhibited signs of mental disturbance (Catanesi et al., 2011; Karakasi et al., 2021). In this theme, it is apparent that perpetrators use the victim as a vehicle for expressing their own feelings and/or desires with a lack of empathy for their suffering (Canter, 1994; Canter & Youngs, 2012). The extreme violence shown may indicate intense feelings of anger or hatred within the perpetrator, which have been projected towards the victim. Such feelings may be a result of a negative perception of the homeless population or may be a consequence of internal conflict brought about by inefficiently treated mental health issues. While it is damaging to assume a cause-and-effect relationship between mental illness and aggression (Silva et al., 2012), research has demonstrated a fluctuating correlation between having been diagnosed with mental health disorders or experiencing symptoms of mental health crises and an increased risk of heightened violence towards others (Chantler et al., 2019; Fox & DeLisi, 2019; Oram et al., 2013). Psychosis as a risk factor preceding violence has received substantial research attention (see Witt et al., 2013 for review) with a proportion of individuals demonstrating a heightened chance of violence during a psychotic episode, particularly when the individual has been subject to trauma during childhood (Pozzo et al., 2021). Other diagnoses, such as Conduct Disorder, have also been associated with an increased risk of violent criminal offending in offenders of a younger age (Davidson, 2014; Loeber et al., 2005; Schorr et al., 2019).

7 IMPLICATIONS

To the knowledge of the author, this is the first attempt to differentiate cases of homicide perpetrated against homeless individuals, providing support for a model of crimes of this nature. The current study provides a foundational framework upon which a theoretical understanding of homeless homicide can be built to develop policies for their intervention and prevention. It must be noted though that the use of this model and the characteristics analysed as an aid in predicting violence or homicide should be done with caution. As warned by several other researchers, using the model in this way would become problematic as individuals may be inaccurately labelled as having the potential to behave in this way with damaging consequences (Greer & Reiner, 2014; Hadjimatheou, 2016; Jones & Cauffman, 2008). Instead, using the proposed model as a foundation for understanding the behaviours and risk factors present throughout cases of homeless homicide, with a stronger focus on helping the victims identified as being at risk may prove to be more fruitful. Variables identified in the inner radex as being present in many cases (victim rough sleeping, victim substance addictions and victim under the influence) demonstrate the growing importance of support services for the homeless as a potential method for preventing homeless homicide by addressing risk factors such as these. As the current study incorporated cases from various locations in England and Ireland, findings may be generalisable to other cases of homeless homicide in the UK. Additional research would be required to test the generalisability of the model in other countries with large homeless populations. This framework can be further tested in future research and if appropriate, can be used to inform intervention policies in reducing violence perpetrated against the homeless population. With homelessness statistics across the UK shown to be increasing, interventions would need to be introduced on a nationwide scale in an attempt to work towards combatting the wider causes of homelessness. Meanwhile, on a smaller scale, interventions should seek to support those who are currently homeless. While the nomadic lifestyle can make the homeless population difficult to contact and monitor, support in the form of outreach services dispatched throughout areas known to have higher number of rough sleepers, for example, city centres (Public Health England, 2020), may be more immediately beneficial in minimising risk. Focussing on the inner radex variables, these outreach services should focus on helping the homeless to access accommodation and support with substance abuse. However, it is acknowledged that these small-scale interventions may not be possible without change at a higher level due to service capacity, funding restrictions, and the limited availability of social housing. This reinforces the crucial need for additional research highlighting the importance of such change.

8 LIMITATIONS

While the current study was successful in identifying three themes of offending throughout the cases of homeless homicide, the study was not without its limitations. Firstly, the data set comprised open-source pre-existing data published online via media outlets. Although all information was cross-referenced and only included if confirmed by two or more sources, the potential for inaccuracy is still present. It is not unheard of for the media to sensationalise or manipulate information in the pursuit of attracting heightened site traffic, omitting details they believe will not be of interest to their readers (Brown et al., 2016; Grabe et al., 2001; Kilgo & Sinta, 2016; Oney, 2004; Scanlon, 2011). The speed at which news outlets process information for publishing can mean that reports are missing information, which would otherwise be considered important to a case (Flynn et al., 2015; Scanlon et al., 1978). Representations such as these throughout the media can lead to an inaccurate understanding of cases or reinforce the stereotyping of the perpetrators (Arendt & Northup, 2015; Bissler & Conners, 2014; Lyon, 2009). The value of information derived from media reports may therefore be limited in its use in empirical research (Cui et al., 2017). Future research should seek to overcome this limitation. If possible, studies would benefit from using case details obtained from official police reports to minimise the potential for inaccuracy. Interviews conducted with the perpetrators of homeless homicide could provide inciteful information to further our understanding of these offences, including their perception of the victim, any motives, personality characteristics or even upbringing.

Studies utilising techniques of analysis such as SSA depend heavily on the sample size of data used. While an initial sample of 28 cases was uncovered following the Internet search, only 19 of them met the criteria for inclusion, including a sufficient amount of information available surrounding each case. It could be argued that in order for the proposed model to be more empirically valid, the sample size would need to be increased. However, the number of cases available for inclusion was also limited to those reported in the media. It is possible that additional cases of homeless homicide occurred within the UK between 2000 and 2022 were not reported by the news outlets. To increase the sample size, it would again be beneficial to utilise official police reports to gather a more valid representation of the scale of homeless homicide cases in the UK.

9 FUTURE RESEARCH

By incorporating police reports into the data collection process, future research would have access to more accurate data on a potentially greater number of cases. This may also allow for the inclusion of a wider scope of variables related to victim, perpetrator and offence and aid in the distinction of themes. Although the current study provides an initial framework for differentiating cases of homeless homicide, further analysis is essential in testing the reliability of the model. Future research should focus on testing this framework across wider samples of homeless homicide cases and explore its applicability to homeless populations in other countries. Should similar themes be uncovered, the themes identified should be tested in their ability to classify cases.

10 CONCLUSION

The current study is the first of its kind to explore the case characteristics of UK homeless homicide offences in an attempt to develop a model of offending. The results of this study, therefore, contribute to the limited amount of empirical data available, which goes beyond merely the prevalence rates of this type of homicide, providing a theoretical foundation to be tested in future research. The hypothesis related to the differentiation of case characteristics was validated as the majority of cases could be assigned predominantly to one of the three themes in the framework. Future research will need to test the validity of the model using a larger sample size of homeless homicide cases. Official police reports combined with interviews with the perpetrators and victims' friends, or family may provide a wealth of information valuable to the exploration of behavioural variation and risk factors. While the study does not address methods of prevention directly, it does provide the empirical groundwork from which techniques of intervention could be developed, with efforts to ensure the safety of potential victims being a priority.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX 1: Variable content dictionary

| Item No | Variable | Variable description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Perpetrator previous violent offences | The perpetrator has previously been convicted for violent offences. |

| 2. | Victim rough sleeping | At the time of the offence, the victim was sleeping on the streets. |

| 3. | Perpetrator homeless | At the time of the offence, the perpetrator was also homeless. |

| 4. | Victim UTI | At the time of the offence, the victim was under the influence of substances, including drugs or alcohol. |

| 5. | Perpetrator UTI | At the time of the offence, the perpetrator was under the influence of substances including drugs or alcohol. |

| 6. | Victim substance addiction | At the time of the offence, the victim was known to suffer from substance addictions, including drugs or alcohol. |

| 7. | Perpetrator substance addiction | At the time of the offence, the victim was known to suffer from substance addictions, including drugs or alcohol. |

| 8. | Bodily weapon | The perpetrator used a body part to attack the victim. This included hitting with fists, kicking, headbutting and biting. |

| 9. | Blunt force weapon | The perpetrator used a blunt force weapon to attack the victim. This included baseball bats, metal bars, wooden planks and stone slabs. |

| 10. | Bladed weapon | The perpetrator used a knife to stab the victim. |

| 11. | Fire as weapon | The perpetrator used fire to attack the victim. This typically involved pouring petrol over the victim or their tent before igniting it. |

| 12. | Drowned | The perpetrator drowned the victim. |

| 13. | Overkill | The perpetrator used force or injured the victim beyond what would be necessary to end their life. |

| 14. | Dismemberment | The perpetrator cut off the victims' limbs prior to or after their death. |

| 15. | Body hidden | Following the offence, the perpetrator made some effort to hide the body. This varied from covering with debris to transporting the body |

| 16. | Multiple perpetrator | The offence was carried out by two or more perpetrators. |

| 17. | Victim—Perpetrator strangers | The victim and perpetrators were not known to one another prior to the attack. |

| 18. | Premeditated | The offence was premeditated in that the perpetrator had purposefully set out to target the victim or was carrying a weapon. |

| 19. | Public place | The offence was carried out in a public place where the potential for others to witness the offence was more likely. |

| 20. | Steals | Following their death, the perpetrator stole possessions or money from the victim. |

| 21. | Perpetrator MH diagnosis | The perpetrator has previously been diagnosed with at least one mental health disorder. |

| 22. | Deception | The perpetrator deceived the victim prior to their death, typically to encourage them to move to an area with no witnesses. |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.